B2A

By Way of a Discovery

Miss Agnes FitzGibbon and Miss Sara Mickle were both founding members of the Women’s Canadian Historical Society of Toronto.1 While Miss FitzGibbon considered herself an author first and foremost, she never achieved the same degree of recognition as her maternal grandmother, Mrs. Susanna (Strickland) Moodie, of Roughing it in the Bush fame. Nevertheless, Miss FitzGibbon did her part to carry on the Strickland family’s literary tradition. By the early 1890s her inspiration had become historical in nature, and in 1894 she published the story of her grandfather, Colonel James FitzGibbon, a veteran of the War of 1812 who went on to become a staunch defender of the Upper Canadian establishment.2 As for Miss Mickle, she too inherited a literary disposition. Her great-grandfather, the Scottish poet William Julius Mickle, was celebrated for his translation of The Lusiads, an epic poem of Portuguese discovery in the New World. Like Miss FitzGibbon, Miss Mickle also developed a strong interest in Canadian history, which would come to find expression in her tireless dedication to heritage preservation.3 In 1895, however, Miss Mickle was content to fulfil her responsibilities as an executive member of the historical society she helped to establish.

Miss Mickle and Miss FitzGibbon worked well together, and by the spring of 1896 they were collaborating on a project. With Miss FitzGibbon acting as her assistant, Miss Mickle began compiling a calendar to commemorate the 400th anniversary of John Cabot’s discovery of North America in 1497.4 The title, however, was somewhat misleading. The Cabot Calendar was never meant to be devoted exclusively to the exploits of the great explorer. Nor was it intended to be a calendar in the conventional sense. What Miss Mickle envisioned, rather, was a chronology of significant events in Canada’s history, organized by month and brimming with line drawings illustrating the glorious past. She also planned to have several full-page monochrome portraits of the country’s most outstanding historical figures, including such famous names as Cabot, Champlain, Frontenac, Wolfe, and Brock.5

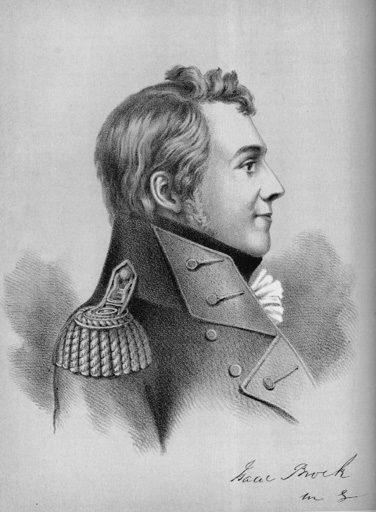

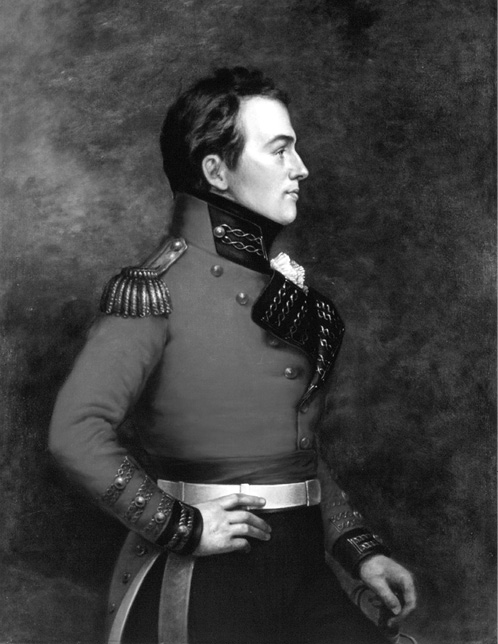

Miss Mickle had little difficulty obtaining suitable copies of the first four portraits, but that of Sir Isaac Brock presented something of a challenge. She was well aware of the profile portrait in John Charles Dent’s Canadian Portrait Gallery (fig. 1), and also the one by John Wycliffe Lowes Forster in David B. Read’s Life and Times of Major-General Sir Isaac Brock, K.B. (fig. 10).6 But neither of these portraits met with her approval, simply because they could not be reproduced to appear consistent with those she had already assembled for her calendar.7 George Berthon’s official portrait of Brock (fig. 9) was also rejected, as it was thought to have lost much of the “intellectuality and personality of the man.”8 More likely, Miss Mickle was simply unable to find a portrait to her liking, and so she continued to search for something better. Eventually, she remembered having heard that someone in Toronto possessed china and possibly other items that had once belonged to Brock. Thinking that this mix might include a more desirable portrait of Brock, Miss Mickle pursued the lead through her informant—who happened to be James Bain, Toronto’s chief librarian.9

Bain directed Miss Mickle to George C. Taylor, a local broom and brush manufacturer.10 It was Taylor’s mother who had the heirlooms, and Taylor believed that a portrait of Brock might be among them, as there was a distant family connection to the famous general.11 Obligingly, he wrote to his mother, Mrs. Heber (Lucy Short) Taylor of Franklin, New Hampshire, explaining Miss Mickle’s interest and asking for further particulars. Word soon came back that there was indeed a portrait of Brock. It was a miniature on ivory, and a most excellent likeness, which Mrs. Taylor was willing to lend for reproduction in Miss Mickle’s calendar.12 This was an exciting development, but the death of one of Mrs. Taylor’s other sons caused an unavoidable delay in arranging the loan.13

Figure 1.

Figure 10.

Figure 9.

Since there was no delicate way to prompt action on Mrs. Taylor’s part, Miss Mickle occupied her time by inquiring into the miniature’s authenticity. This she did by investigating all the earlier owners, and also the relationship between Mrs. Taylor’s ancestors and Sir Isaac Brock. After consulting a book, possibly David B. Read’s biography of Brock, and communicating further with George C. Taylor, Miss Mickle followed up by seeking the advice of Mrs. Robert (Sarah Anne Vincent) Curzon, a friend from Toronto who had written about the Battle of Queenston Heights. Mrs. Curzon advised a letter to James Le Moine of Quebec City, as he was a tireless scholar of French Canadian history and someone who might have information on Brock’s Canadian relatives—given that they hailed from la belle province.14 While Le Moine seems to have been limited in the assistance he was able to provide, Miss Mickle tended to believe the family tradition that described how the miniature passed from Brock’s cousin down through his Canadian and American descendants. As Miss Mickle understood it, Mrs. Taylor inherited the miniature from her great-aunt, Mrs. George (Matilda Short) Dunn of Three Rivers, or Trois-Rivières, Quebec. The miniature had been left to Mrs. Dunn by her sister, who was the widow of Captain James Brock, and who had in turn obtained it from the estate of his cousin, Major General Isaac Brock. Reinforcing this provenance was Mrs. Taylor’s recollection that Mrs. Dunn had identified the sitter as Sir Isaac Brock.15 Miss Mickle was favourably inclined, but no matter how much she wanted to believe that the miniature was actually Brock, it remained to be seen whether or not this much-anticipated likeness would be appropriate for The Cabot Calendar.

In June of 1896, after more than a month, Miss Mickle finally received the miniature (fig. 11).16 It was well worth the wait, as this new portrait of Brock was positively enchanting. The officer it portrayed was young, handsome, and noble looking. Miss Mickle was overjoyed, and so too was her associate. Miss FitzGibbon had nothing but praise for the miniature. “It is an unmistakable likeness,” she asserted, “a face showing power and strong determination, loveableness and straightforward manliness of character; a face which explains why his soldiers obeyed him, loved him so dearly and followed him so devotedly, and why he has won so high a place in the hearts of the people of Upper Canada, a veritable Sir Isaac Brock.”17

The miniature was perfect, possessing as it did all the characteristics one would expect of a heroic figure like Brock. It was also perfect for The Cabot Calendar, and Miss Mickle wasted no time in having it photographed (fig. 12) in order to begin the process of lithographic reproduction.18 She was rather disgusted, however, when the artist making the halftone thought he recognized the likeness.19 The Misses Mickle and FitzGibbon were hoping to keep the discovery “quiet,” in order to boost sales by having the announcement of a newly discovered miniature of Brock coincide with the release of The Cabot Calendar. But word of the miniature was spreading fast. It was already the main topic of conversation at the Toronto Public Library, where George C. Taylor had shown it to librarian Bain. But as much as Miss Mickle and Miss FitzGibbon were annoyed by all this unwelcome attention, they themselves were partly to blame—having allowed Mrs. Curzon the same indulgence of a personal viewing.20

Figure 11.

As work progressed on the calendar, the miniature was restored by Gerald S. Hayward, a prominent American miniature painter who was then visiting Toronto.21 Hayward’s home was on New York’s Long Island, but he was born in Canada and still made the occasional trip back to his native land.22 Earlier, after examining the miniature, he agreed to undertake the restoration, which was done at George C. Taylor’s expense. However, it was Miss Mickle who did all the negotiating, and it was during this interaction that Hayward offered to paint her a copy.23 Miss Mickle readily agreed to the proposal, although it was only a short time later that she managed to purchase the original.24 While the date of this transaction is not known, it likely came about after Hayward completed his copy, as such a duplicate would have been pointless once Miss Mickle became the proud owner of the original miniature. And whether or not she regretted her haste in commissioning Hayward, Miss Mickle did get value for the money she handed over to him.

Figure 12.

In addition to Hayward’s artistic services, Miss Mickle made good use of his expertise in assessing the miniature, which was the work of an elusive artist known only as J. Hudson. Specifically, she wondered if he could explain the peculiar manner in which the miniature had been dated. It looked to be “18X6,” and according to Hayward the “X” was meant to represent zero, “as we often do now on cheques.”25 This interpretation seemed logical enough, since Brock was known to have been in England during 1806. The miniature could also have been painted in London, as it was likely there that such an exquisite portrait would have been commissioned. Moreover, Brock was then in his mid-thirties, and the sitter appeared to be roughly the same age. Hayward also thought the medal, which was prominently displayed on the sitter’s chest, must have been awarded to Brock for his service at the Battle of “Egmont-op-Zee” in 1799.26 It all seemed quite plausible to Miss Mickle, and she was not about to second-guess Gerald S. Hayward when he was arguing her case.

Although the copy of the miniature (fig. 13) and the restored original were both delivered by mid-August of 1896, Miss Mickle was becoming impatient.27 She was anxious to announce her great discovery and launch the pre-Christmas sales of The Cabot Calendar, but there was someone else she wanted to consult. It was Allan Cassels, a Toronto lawyer whose opinion mattered a great deal to Mickle.28 However, in showing him the miniature (fig. 11), she was dismayed to find his reaction more critical than congratulatory. Upon scrutinizing the uniform, Cassels noticed that it looked as though it was rapidly filled in, which indicated the work of a less talented artist. Oddly, nothing was known about the quality of Hudson’s portraiture, and so the criticism was probably meant to cast doubt on the miniature and thus diminish its importance. As Miss Mickle recalled, Cassels “thought the miniature had been probably painted after death from another picture, [and] that it would be found to be a copy.”29 Miss Mickle was not at all pleased with this critique, but she knew how to neutralize it.

In returning to Hayward, Miss Mickle repeated the concerns expressed by Cassels. Yet, Hayward remained firm in his convictions. While he admitted that the uniform might have been painted rapidly, he saw no reason to believe that it had been done by a “different hand.” Nor was the miniature a copy, as it was obviously done from life. And just because Miss Mickle and Miss FitzGibbon could find no record of J. Hudson, it did not automatically make him a less talented artist as Cassels suggested. There were many good artists who never managed to make a name for themselves. But in order to be absolutely sure, Hayward compared the miniature with every other portrait of Brock he could find, and in each case he judged the face to be the same. The only difference was the superior workmanship of the miniature discovered by Miss Mickle.30

Figure 13.

When Miss Mickle presented Cassels with a copy of Hayward’s opinion, the lawyer promptly conceded. “I am very glad to hear from you about the Brock miniature,” Cassels wrote early in September of 1896. “Whatever Hayward says about its being taken from life is sure to be correct and you bring it at once within historic interest. All these memorials will some day or other be of great value, and I hope you will be duly acknowledged as its discoverer and preserver for it was certainly in great need of restoration.”31 Although Cassels was not completely won over, he was by no means prepared to engage in a heated debate over a questionable miniature of Sir Isaac Brock. Miss Mickle was very pleased with this outcome, and also with herself.32 She held her ground, not her tongue, and in the process proved herself capable of standing up to a man—and not just any man, but a prominent lawyer. It was an empowering experience for a Canadian woman in the late nineteenth century, but despite Miss Mickle’s newfound confidence, she was hardly a publicity seeker.

In the end, it was agreed that Miss FitzGibbon should be the one to break the news about the miniature. Accordingly, she chronicled Miss Mickle’s discovery in a long letter to the editor of the Toronto Globe.33 Then, after a bit of free advertising for The Cabot Calendar, Miss FitzGibbon turned her attention to Berthon’s portrait of Brock (fig. 9), which she criticized in an unnecessarily severe manner. “Whether taken from a good original or not,” she declared, “the copy [by Berthon] is not a masterpiece, and the copies from it as well as photographs taken at various times, the negatives of which have been touched up to suit the ideas of the photographer, are even less so.”34 In further denouncing Berthon’s portrait as a “lifeless presentment,” Miss FitzGibbon was no doubt trying to enhance the importance of the miniature discovered by Miss Mickle. At the same time, however, she must have also known that any attack upon the official portrait of Brock was bound to cause a stir.

Sure enough, Miss FitzGibbon’s letter drew the ire of someone writing from Toronto, and under the cover of a nom de plume. “Historian” took offence with the harsh remarks about Berthon’s portrait of Brock, and assumed that Miss FitzGibbon was critical of the portrait simply because it was painted in profile. Yet, “Historian” came to this erroneous conclusion even though Miss FitzGibbon merely made reference to the lithographic artist’s opinion, namely that Berthon’s portrait of Brock could not be reproduced in a manner consistent with those of Cabot, Champlain, Frontenac, and Wolfe.35 Evidently, “Historian” had yet to see a copy of The Cabot Calendar, with its profile portraits of both Frontenac and Wolfe. In fact, Miss FitzGibbon’s complaint had nothing to do with the pose Berthon used for his portrait of Brock. Rather, it was the portrait’s quality, which Miss FitzGibbon found lacking. Yet, judging from Berthon’s very fine rendering, she probably only saw photographs of the portrait and not the portrait itself.

There was a great deal of confusion on both sides, and misconceptions were lobbed back and forth across the columns of the Globe. For “Historian,” who still had the floor (so to speak), it was unfair to judge the quality of a portrait based on the pose of its sitter. As for the allegation of retouched negatives, “Historian” defended the photographs taken of the portrait of Brock by Forster—which was commissioned by John A. Macdonell in 1894 (fig. 10). While these were not in fact the photographs Miss FitzGibbon had in mind, “Historian” used them to argue that the “intellectuality and personality” of the portrait, supposedly lost in the dark room, was actually “most noticeable,” even if it was a profile portrait. Finally, in response to Miss FitzGibbon’s criticism that Berthon’s portrait was a “lifeless presentment,” “Historian” simply excused it as “a pardonable [or understandable] enthusiasm under the circumstances.”36 And far from resenting Miss Mickle’s discovery, “Historian” welcomed the miniature of Sir Isaac Brock . . . in so much as it complemented the official portrait by Berthon.

“Historian” was very likely one of the Robinsons; however, not the former lieutenant governor, as the Honourable John Beverley Robinson was dead.37 Neither was it Colonel (now Major General) Charles W. Robinson, since he was still living in England whereas “Historian” wrote from Toronto.38 That city, however, was also home to another Robinson brother. As a gifted lawyer with a highly developed sense of diplomacy, Christopher Robinson could very well have been responsible for a carefully worded protest.39 He was also a very retiring sort of gentleman, and just the type of person who might have made use of a pseudonym.40 And he most assuredly would have objected to Miss FitzGibbon’s trouncing of Brock’s official portrait, if for no other reason than it was commissioned by his late brother.

In her reply, Miss FitzGibbon began by chastising people such as “Historian” for not having the courage to identify themselves when expressing their opinions. And yet she herself also became fairly guarded, refraining from further comment on Berthon’s portrait of Brock. Instead, she changed the subject by giving Miss Mickle credit for noticing subtle differences among the several profile portraits of Brock. Similar findings were reported by Miss Janet Carnochan, a teacher and historian from what is now Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ontario, which led Miss FitzGibbon to speculate that there were other portraits of Brock waiting to be found.41 What she failed to consider, however, was the possibility that most of Brock’s portraits were merely variations on the original profile portrait (fig. 3).42

Regarding the retouched negatives, Miss FitzGibbon appears to have thought the photographs discussed by “Historian” were duplicates of the one Berthon used for his portrait of Brock or, in other words, the photographs of the original profile portrait owned by Mrs. Tupper in Guernsey. As already noted, however, it was actually the portrait of Brock painted by Forster that “Historian” visualized when he penned his own letter to the editor. Miss FitzGibbon, however, was none the wiser and readily confessed that the “half dozen photographs taken for private gifts from the original miniature in the possession of Mrs. Tupper” were not available to Miss Mickle and herself when they began work on The Cabot Calendar.43 Despite this minor concession, she had no intention of retracting her allegation of retouched negatives—not when she recalled how the doctored pictures were sold as souvenirs at the Lundy’s Lane Observatory (a scenic look-out tower near Niagara Falls). Whether or not these cheap productions were really “touched up” photographs of the original profile portrait of Brock, Miss FitzGibbon remained defiant. But there was no rebuttal from “Historian,” who seems to have given up the fight. Perhaps it had something to do with a low tolerance for frustration. Whatever the case, Miss FitzGibbon must have derived great satisfaction from having silenced her newsprint opponent.

Notwithstanding “Historian’s” interference, The Cabot Calendar was well received.44 So too was the new portrait of Sir Isaac Brock it contained (fig. 14). No one else took exception with Miss Mickle’s discovery, at least not publicly. It might have been out of fear, as even the most innocent query could unleash the fury of Miss FitzGibbon’s very public wrath. Such an apprehension may have influenced a perplexed lawyer from Montreal, whose suspicions were aroused by this new portrait of Brock.45 David Ross McCord was an avid collector of Canadiana. He was also an occasional correspondent of Miss Henrietta Tupper in Guernsey, as she possessed a number of Brock-related artifacts that he had a mind to acquire for his collection. Years earlier, she kindly supplied him with the profile portrait of Brock, or rather a photograph of the copy owned by Mrs. Huyshe (fig. 4), which seemed authentic until The Cabot Calendar was published in 1896.46 When McCord saw the new likeness of Brock, he dispatched one of the calendars to Miss Tupper in hopes that she might be able to enlighten him. She could only agree that “the supposed portrait of Sir Isaac differs very considerably from that which was painted from the miniature [meaning the profile portrait].”47 But if Miss Tupper had misgivings about the authenticity of this new portrait, she kept them largely to herself. McCord did likewise. The Robinsons, however, were not nearly so discreet.

Figure 14.

In April of 1897, disturbing rumours began to circulate about Miss Mickle’s discovery. This scuttlebutt began in England, where Major General Charles W. Robinson had good reason to doubt that the miniature actually featured Sir Isaac Brock. Much of the general’s uncertainty had to do with the uniform. Brock was known to have been a full colonel at the time the miniature was ostensibly painted in 1806; yet the uniform suggested that of a lower ranking officer.48 The medal, which the miniature painter Gerald S. Hayward linked to Brock’s service at the Battle of Egmont-op-Zee in 1799, was also suspect. General Robinson believed it to be the Military General Service Medal of 1847, which to the best of his knowledge was not awarded posthumously.49 Therefore, it could not have been an honour bestowed upon Brock, as he was killed in 1812—some thirty-five years earlier. In trying to come up with a rational explanation for this discrepancy, the general decided that someone must have altered the miniature at a later date.50 While such an alteration did not rule out Brock as the sitter, General Robinson remained skeptical. It was very difficult for him to believe that Miss Mickle could succeed in finding such an important portrait, especially when Brock’s regiment had failed in the same endeavour.51 The fact that the miniature had been copyrighted was also very telling, and General Robinson thought he knew the truth behind Miss Mickle’s discovery. The whole affair was nothing more than “an attempt to foist a false portrait on the public and make money out of it.”52

Disregarding all the mean-spirited gossip, Miss Mickle remained calm and even philosophical. As for the general, he was just upset that another portrait of Brock had come to light. Yet, he also seemed “very anxious not ‘to be dragged into any controversy’ over it.”53 Miss Mickle was right. General Robinson had no desire to spar with a woman in one of Canada’s leading dailies. Such behaviour on the part of a gentleman would have been unseemly, and probably explains why the general decided on a more devious course of action. It was a letter-writing campaign involving his brother, Christopher Robinson, and his sister, Mrs. James (Augusta Robinson) Strachan. This low-key approach suited the general, who knew he could count on his siblings to cast doubt on the miniature’s authenticity. Before long, Miss Mickle was made aware of General Robinson’s poison pen letters, which goaded her so much that she boldly asked Mrs. Strachan for copies of them. Not surprisingly, the general’s sister declined the request.54

Miss Mickle appears to have been genuinely astonished by the refusal, as it was no secret that Mrs. Strachan had shown the letters to others of their mutual acquaintance. Both Miss Mickle and Miss FitzGibbon suffered hurt feelings as a result, but Miss FitzGibbon was particularly wounded, as she and Mrs. Strachan had been life-long friends.55 The slight also confirmed Miss Mickle’s fear that General Robinson was trying to build a case against the miniature. While it was unclear whether or not he would go public with his rumours of fraud, the Misses Mickle and FitzGibbon thought it best to prepare for that eventuality. They resolved to counteract any effort by the general to denounce the new likeness of Brock, and they had good reason to be apprehensive: it appeared that John Wycliffe Lowes Forster was on the general’s side.

Having ingratiated himself with the late lieutenant governor for the sake of obtaining props and other materials by which to paint his own portrait of Brock (fig. 10), Forster was firmly embedded in the Robinson camp.56 But even if Miss FitzGibbon and Miss Mickle were unaware of this arrangement, there were other indicators of Forster’s allegiance to the Robinsons. The first ominous sign came soon after Miss Mickle’s discovery was first announced in September of 1896, when the Toronto Globe suddenly carried an article highlighting Forster’s artwork. Included was a large picture of the Brock portrait commissioned by John A. Macdonell, along with a careful accounting of its authenticity.57 Forster’s partiality to the Robinsons was evident throughout the write-up, and things only got worse several months later when a troubling report came to hand: Forster was preparing for a trip abroad to continue his studies in Paris, and he was also planning to visit Guernsey, where he expected to “fulfil a commission.”58 With this news, Miss Mickle and Miss FitzGibbon became convinced that Forster was in the employ of General Robinson, and that his unspecified commission would somehow serve the Robinson interests to the detriment of their own.

Miss Mickle reacted by making it her mission to find an ironclad confirmation, and by whatever means necessary, that her newly discovered miniature (fig. 11) was actually a portrait of Sir Isaac Brock. This she did by means of several letters to various people asking pointed questions about the miniature’s provenance. But in striving to find supporting evidence for her discovery, Miss Mickle happened upon a sizeable complication. Mrs. Dunn, who bequeathed the miniature to her great-niece (Mrs. Heber Taylor), apparently also had another portrait of an officer (fig. 15) said to be a “picture of a general in uniform.”59 This other portrait—apparently a medium sized oil painting—belonged to Mrs. Taylor’s sister, Mrs. Alfred (Matilda Short) de Beaumont of Montreal, and Mrs. de Beaumont was quite insistent that it portrayed Sir Isaac Brock. She was also convinced that the miniature owned by her sister was a portrait of their great-aunt’s late husband, Captain George Dunn. This unwelcome news was quite a shock to Miss Mickle, as it disputed the identification of the miniature she had purchased from Mrs. Taylor. The resulting dilemma was potentially far more damaging than all of the gossiping Robinsons combined. And since The Cabot Calendar featured one of the two portraits under discussion, Miss Mickle could only hope that it was hers that proved to be authentic.

Figure 11.

Figure 15.

Exactly how Miss Mickle became aware of Mrs. de Beaumont’s so-called portrait of Sir Isaac Brock is not known. It may have been mentioned in one of the letters she received while attempting to confirm the authenticity of the miniature. However, by the end of April 1897, Miss Mickle raised the matter of Mrs. de Beaumont’s portrait of Brock with the Reverend Henry C. Stuart of Trois-Rivières. She had already communicated with him some months earlier regarding the relatives of Captain James Brock, presumably while conducting due diligence on the miniature.60 In taking up her cause once again, Rev. Stuart wrote to one of Captain Brock’s nephews, an old gentleman in Montreal by the name of George S. Carter.61 Anticipating that Mrs. de Beaumont might know something about the portrait, Carter took the liberty of paying that lady a visit. Mrs. de Beaumont repeated her story and provided other information as well, all of which Carter passed on to Rev. Stuart. In addition, Carter described the portrait, pronouncing it to be a “beautiful miniature [or rather a small painting] of the General in full regimentals, and as bright and fresh looking as when it was turned out of the hands of the artist who painted it.”62

Having enquired after the portrait, which he was led to believe was that of Sir Isaac Brock, Carter thought there might be some interest on Miss Mickle’s part in purchasing it. “Mrs. De Beaumont has promised to hold the picture subject to my wish and pleasure, but plainly hinted that she would not part with it without a quid pro quo.”63 Rev. Stuart, however, questioned Carter’s investigative skills, thinking instead that the portrait might be of Captain James Brock or perhaps even Lieutenant Colonel William C. Short (who was killed at the Battle of Fort Stephenson in 1813).64 But Miss Mickle completely disregarded Rev. Stuart’s speculations. She was far too fixated on the authenticity of her miniature, now that the collateral descendants of Captain James Brock appeared to be in the business of selling portraits of Sir Isaac Brock.

After skirting the issue as much as possible, Miss Mickle had no choice but to seek clarification from the lady who sold her the miniature in the first place. But Mrs. Taylor did not appreciate the tone of Miss Mickle’s letter, which insinuated that the identity of the sitter may have been misrepresented for financial gain. “I assure you, Miss Mickle, my [great] Aunt [Mrs. Dunn] had no interest in making a false statement relative to the Portrait of Sir Isaac Brock, and I may also say neither had I.”65 Mrs. Taylor was adamant that the miniature she sent to Toronto was authentic, and while she was on the topic of miniatures, she closed her letter by observing: “I think it very likely Sir Isaac had more than one.”66 Miss Mickle, however, was not interested in any and all miniatures of Brock—just the one she had come to cherish.

In mid-May of 1897, Miss Mickle carried on with her interrogations by addressing a letter to Frederick M. Short. Like George S. Carter, Short was an aged nephew of Captain James Brock. He was also Mrs. Taylor’s uncle, and it just so happened that he lived with her in Franklin, New Hampshire.67 In complying with Miss Mickle’s request for information about the miniature, Short recounted a painful incident from his childhood. “When I first came to Canada, Mrs. James Brock (my Aunt) was shewing me the Pictures in her Parlor and told me that [miniature] was the Portrait of Sir Isaac Brock and that he was a famous Soldier and cast up to me that if I had accepted the Commission in the British Army, which she had got the promise of for me, I might have been some day a famous man too, but as I had refused I need not expect any favours from her.”68 The boy never forgot the reproach, and he had no hesitation in stating that the miniature at the centre of this odd story (fig. 11) was the same one his niece had sold out of the family.69 Unfortunately for Short, he appears to have been either mistaken or mendacious. But on a more positive note, he also claimed to be familiar with the portrait owned by Mrs. de Beaumont (fig. 15), which he positively identified as his elderly uncle: Captain George Dunn. Since he supposedly knew his uncle’s features from personal experience, Short might have been well qualified to dispute Mrs. de Beaumont’s portrait of Sir Isaac Brock. But Miss Mickle was not overly impressed with Short’s story, and she reacted to it by seeking further assurances from him.

In his reply, Short tried a new tack by vehemently expressing his low opinion of Mrs. de Beaumont’s painting. “That Picture to my mind represents a wild Harum Scarum man.” While Short was quick to apologize for his use of this expression, which was rather inappropriate for a lady, he knew “of no other that will so aptly describe the Picture in question.”70 After all, the sitter gave the impression of “a man more fitted for a Lunatic Asylum than one to command the love and Esteem of his men.”71 This line of reasoning was utterly ridiculous, of course, but it probably helped sway Miss Mickle into thinking that Mrs. de Beaumont’s portrait might not be Brock after all. Mrs. Taylor came up with an even more compelling argument: “As for the Portrait which Mrs. de Beaumont has, I most emphatically say [it] is the Portrait of Capt. Dunn. I think I have a good right to know, as I had it to veil & unveil twice a day for Mrs. Dunn to lament over.”72 Years earlier, Mrs. Taylor had been responsible for taking care of her bedridden great-aunt, and one of her duties included a very peculiar ritual.73 Every night, she took the portrait down from the wall and placed it near the foot of the old lady’s bed, while at the same time having to endure her aunt’s repeated cries of “Dunn! Dunn! Why did you leave me?”74 Given this bizarre behaviour, Mrs. Taylor had no doubt as to the identity of the officer in this portrait.75 Without a doubt, it was Captain—or more accurately Lieutenant—George Dunn.76

As far as Mrs. Taylor and her uncle were concerned, the miniature sold to Miss Mickle was now effectively authenticated as being that of Sir Isaac Brock. Miss Mickle, however, was still not entirely persuaded, and so she must have been thankful for Miss FitzGibbon’s generous offer to seek out the opinions of some art experts in London. If these specialists could agree that the likeness in the miniature was the same as those in the profile portraits, it would serve to validate Miss Mickle’s discovery. This strategy might have been inspired by the comparisons made by Gerald S. Hayward, who assured Miss Mickle that the miniature she purchased compared favourably with every other portrait of Brock he could find. In any case, it was a happy coincidence that Miss FitzGibbon was planning to set out for England only a few weeks after Forster took his leave.77 Although Miss FitzGibbon’s trip had nothing to do with Brock, she was determined to assist Miss Mickle in authenticating the miniature—even if it meant adjusting her itinerary.

Miss FitzGibbon’s first stop was New York City, where she made a detour in order to visit Gerald S. Hayward on Long Island. Over tea, she told her host all about General Robinson’s hostility towards Miss Mickle’s discovery. Hayward was “intensely amused,” and confidently ruled out the possibility that there had been any tampering with the miniature (fig. 11). He was also certain that the medal was not a later addition, and even if he had failed to notice it as such, “the lens would have done so when it was photographed.” With regard to the uniform, it was absurd to think that “any such minor changes in the style or cut of the trimmings” could be assigned a specific date. Furthermore, “no critic whose authority was worth having on such a question could avoid recognizing the fact that the profile and the miniature were one and the same person.”78 Hayward’s unshakable faith in the miniature was encouraging, and Miss FitzGibbon parted company with him feeling very optimistic.

Arriving in London at the end of April 1897, Miss FitzGibbon found the city “full to over flowing” with people from all over the British Empire.79 They had come to celebrate Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee, which greatly annoyed Miss FitzGibbon as it forced her to go in search of lodgings beyond the capital. After getting herself settled in, she returned to London and eventually made her way to the Royal Colonial Institute—a learned society that promoted discourse on a wide range of subjects.80 The main attraction for Miss FitzGibbon was a fairly impressive library, and it was there that she began her search by consulting James R. Boosé, the Institute’s librarian. During their conversation, Miss FitzGibbon stopped short of saying anything about General Robinson or the newly discovered miniature of Brock. She simply voiced a desire to verify the “authentic data” (or compelling evidence), which she and Miss Mickle already possessed.81 Miss FitzGibbon was thinking in terms of the uniform and medal in the miniature, both of which General Robinson seemed to doubt. Boosé, however, could do little more than offer a referral to his counterpart at the Royal United Service Institution, as Major Robert M. Holden was known to have made a comprehensive study of uniforms and medals.

A few days later, Miss FitzGibbon paid a visit to the Royal United Service Institution, an organization dedicated to the study of military and naval science. In asking for Major Holden, she was disappointed to learn that he was out. She returned several hours later, only to find that he had gone off to a lecture. Miss FitzGibbon was becoming extremely frustrated.82 Nor did her mood improve when she went to register for mail delivery at the Canadian High Commission. While there, she discovered that Forster had put in a request to have his mail forwarded to Guernsey. As she rhetorically asked in her next letter to Miss Mickle, “what has brought Forster to Guernsey if not to get ahead of us about the portrait—prove his & disprove ours[?]”83 Paranoia was getting the better of Miss FitzGibbon, and Major Holden’s continued absence only made it worse.

The next morning, Miss FitzGibbon returned once again to the Royal United Service Institution. And once again, she was told that Major Holden was out. This time, she left him a note requesting a meeting for later that afternoon. It was perhaps a test to determine if she was being ignored, as she was given to believe that he would be back by three o’clock. But upon her return, Miss FitzGibbon finally managed to catch up with the elusive major, who enthusiastically asked what he could do for her. “I have a miniature here,” she bluntly rejoined, “that I wish to show you and ask what the uniform in it is. I think that perhaps will be the shortest and most straightforward way of arriving at the information I want.” Somewhat taken aback, Major Holden could only answer “certainly, you are right.” As soon as he saw the miniature (fig. 11), or rather a photographic copy, he recalled having seen it before. When Miss FitzGibbon demanded to know where, the major replied “General Robinson brought it to me.” And when Miss FitzGibbon insisted on knowing in what form, she was told a “pamphlet or circular, or something of the kind,” which could only be taken to mean one thing: The Cabot Calendar. “Yes,” said Miss FitzGibbon, “and what was your opinion?” The major confessed he was unable to make out the medal, which General Robinson specifically enquired about, although he suspected that it “probably had been painted on the miniature later.”84

With this brief exchange, Miss FitzGibbon suddenly realized that she had located the chief source of General Robinson’s information. Now it was her turn to exploit Major Holden’s good-natured willingness to help, and this time to Miss Mickle’s advantage. Unfortunately for Miss FitzGibbon, the major could not venture an opinion regarding the miniature’s authenticity. But eager to be of some assistance, he helpfully intimated that artists often painted uniforms “to suit their artistic fancies.”85 Suddenly, the uniform was no longer an issue, and neither was the medal.86 The major’s insight was most gratifying, as it completely dispelled General Robinson’s contention against the miniature.87

Having finally met Major Holden, Miss FitzGibbon developed a favourable opinion of the gentleman. While he was not as helpful as she would have liked, neither did he appear to be on the side of General Robinson. It was a great relief, and when the major offered to do anything he could to help her, Miss FitzGibbon took him at his word.88 In dropping her guard, she told him all about General Robinson’s objections, and how she and Miss Mickle were “perfectly well satisfied” with the authenticity of the miniature, but thought it “only right” to make further enquiries. Miss FitzGibbon also let it be known that she was going to Guernsey, “to learn if there were any other members of the [Brock] family who could by any possibility have sat for this miniature.” Before parting company with Major Holden, she felt the need to explain why the miniature had been copyrighted, which she claimed was only done to prevent it being reproduced in all sorts of “horrible newspaper prints.”89 Miss FitzGibbon added that the legal protection was vested in Mrs. Taylor.

This last revelation was intended to dispel any notion that Miss Mickle and Miss FitzGibbon hoped to make money out of Brock’s new portrait. Nevertheless, the prospect of turning a profit from Miss Mickle’s discovery had been a consideration right from the start—although the miniature was beginning to look much less lucrative than it first appeared. The costs associated with proving the identity of the sitter were beginning to mount and, as Miss FitzGibbon explained to Miss Mickle soon after her meeting with Major Holden, “even if we do prove its authenticity to such men as General Robinson, the doing so will be so expensive that it will be years before we get even interest on the outlay.”90 However, Miss FitzGibbon also thought a financial disappointment in the meantime would at least “prove that we are—perforce perhaps—honest in saying that we do not expect to make money out of it.”91

On the same day that Miss FitzGibbon met with Major Holden, she received a letter “most kind” from Guernsey. In it, Miss Henrietta Tupper invited her to visit, adding that Forster had already introduced himself to the Tuppers and other Brock relatives. As Miss Fitzgibbon noted for Miss Mickle’s benefit, “they find him interesting—but say no more.”92 Faced with such ambiguity, Miss FitzGibbon was very discreet in her reply to Miss Tupper and careful not to say anything untoward about Forster. Rather, she feigned a desire that “he will be still there when I arrive, as I know him slightly.”93 Forster’s head start gave Miss FitzGibbon cause to be wary. She had no idea what he might have said about Miss Mickle’s discovery, or how it might be perceived in Guernsey. Ultimately, there was only one way to find out.