B3A

All to Prove a Point

It was sometime around the middle of May 1897 when Miss FitzGibbon stepped onto the pier at St. Peter Port, the capital of Guernsey and birthplace of Sir Isaac Brock. She was on her way to visit Miss Henrietta Tupper, whose friendly reception must have come as a great relief. Far from being unduly influenced by John Wycliffe Lowes Forster, Miss Tupper was well disposed to the idea of another portrait of Brock. Much of her indulgence had to do with the claim that Captain James Brock owned the miniature at one time. Miss Tupper was well aware that Captain Brock was a first cousin to Sir Isaac Brock, and that he had served in Canada as paymaster to the 49th Regiment. It was therefore conceivable that Captain Brock might have owned a miniature of his cousin, and that his family in Canada would have preserved such a prized heirloom. With her curiosity thus piqued, Miss Tupper was only too happy to help Miss FitzGibbon with the investigation.1

The first order of business was to enquire after Lieutenant Colonel J. Percy Groves of the Royal Guernsey Militia, who was also librarian of the Candie Library in St. Peter Port and a military historian of some renown. Because Miss Tupper and the rest of her family valued his opinion, Miss FitzGibbon thought it best to ask him for his interpretation of the uniform and medal worn by the officer in Miss Mickle’s miniature.2 However, there were no expectations on her part, as Major Robert M. Holden had already decided that both of these attributes were merely “artistic fancies.” Despite a thorough search, Colonel Groves was unable to be of much assistance—although he did raise the possibility that the medal might have been awarded for the Battle of Waterloo.3 Considering that this battle took place in 1815, nearly three years after Brock’s death, Miss FitzGibbon dismissed the suggestion . . . and the colonel himself.4

Believing that Colonel Groves had been tainted by Forster’s bias, Miss FitzGibbon tended to ignore his expertise.5 However, if the colonel was a disappointment, then Miss Guille more than made up for it. Miss Mary Elizabeth Guille was a septuagenarian whose maternal grandfather was one of Sir Isaac Brock’s first cousins.6 She was very smart for her age, and she had a vivid recollection of Brock’s brothers—Daniel de Lisle Brock and John Savery Brock. Miss Guille was therefore an important witness to history, and one who happened to tell Miss FitzGibbon exactly what she wanted to hear. Upon seeing one of the photographs of the newly discovered miniature (figs 12, 17), Miss Guille did not hesitate in pronouncing the sitter to be a Brock. Miss FitzGibbon presumed that she meant Sir Isaac Brock.7

Miss Guille’s conviction prompted an acceptance of the miniature by the other Brock relatives, and of the charming Canadian lady who brought the pleasing miniature to their attention. Miss FitzGibbon was careful to cultivate a good relationship with Brock’s extended family, and one of their number—a Mrs. Bubb—was “very much impressed by the clear, precise manner in which Miss FitzGibbon explained everything. She has the subject not only at her finger’s ends, but at her heart, and I did wish like you, that our dear Fathers and Aunt de Lisle could have met her—they could have told her so much more than we can, in fact I believe she knows more than we do. She is certainly a woman one does not meet every day, and I felt much drawn to her. I hope to see more of her.”8 Miss FitzGibbon had a knack for winning people over, but she also knew that no amount of charisma could guarantee the entire Brock family’s support for Miss Mickle’s discovery. And she still had to contend with the objections of Major General Charles W. Robinson, which Forster was sure to raise whenever possible. The most effective means of countering Forster’s negativity would have been for Miss FitzGibbon to reveal his complicity in the general’s scheming, but she worried that such a bold disclosure might reflect badly on herself. In a stroke of good luck, however, the general soon became his own worst enemy.

One morning during breakfast with Miss Tupper, Miss FitzGibbon saw an opportunity to enlighten her new friend.9 As the two ladies sat enjoying each other’s company, the post arrived with a packet addressed to “F. Brock Tupper Esq.”—the sight of which gave Miss Tupper such a shock that she dropped it on the table. “Who,” she exclaimed, “can be writing to me who does not know my father is gone!”10 In picking up the packet, Miss FitzGibbon found a clue written on the back, which she read out: “Gen[eral] R does not want the enclosed picture back, so please do not trouble to return it.”11 Miss Tupper was intrigued that General Robinson had something to do with the packet, and inside she found a letter from a Mrs. Lewin—who years earlier had acted as something of an agent for Miss Alice Kerr-Nelson. It was Miss Kerr-Nelson who had made the copy (fig. 6) of Mrs. Henry Tupper’s profile portrait of Brock (fig. 3) for Lieutenant Governor John Beverley Robinson.12 Also enclosed was a page from The Cabot Calendar with the lithographic illustration of Miss Mickle’s miniature (fig. 14), and a letter from General Robinson to Mrs. Lewin enquiring if the Brocks in Guernsey had any knowledge of this additional portrait. For Miss FitzGibbon, it was the perfect setup.

The timely arrival of Mrs. Lewin’s packet allowed Miss FitzGibbon to broach the subject of General Robinson’s objections to the miniature, by which she hoped to lower Miss Tupper’s now diminished estimation of him. By making his request through Mrs. Lewin, instead of going directly to Miss Tupper, General Robinson appeared to be acting in a clandestine manner. Miss FitzGibbon further capitalized on the general’s misstep by expressing her disapproval of his having written “in so underhand a way,” which she judged to be very “ungentlemanly.”13 She then proceeded to blurt out all the problems she and Miss Mickle were having with him, and how he was surreptitiously undermining the credibility of the newly discovered miniature of Brock (fig. 11).

Miss Tupper was sympathetic and promised to write a fitting reply, which led Miss FitzGibbon to believe that General Robinson would soon have his comeuppance.14 She also expected him to get the message that Miss Tupper was firmly on Miss Mickle’s side. But in writing to tell Miss Mickle about her good fortune, Miss FitzGibbon became somewhat defensive as she recounted how she had manipulated Miss Tupper. In downplaying her own bad behaviour, Miss FitzGibbon claimed that Miss Tupper knew how carefully she was conducting the investigation, and how it would always be carried out “honestly and in search of the truth.”15 In fact, Miss FitzGibbon’s perception of the truth in this instance was more than a little slanted in favour of Miss Mickle’s discovery. And yet she was absolutely convinced that this new portrait of Sir Isaac Brock was genuine and that its case could be argued successfully. She had already persuaded most of the Brock relatives that Miss Mickle’s miniature was authentic, which was reassuring . . . until it became evident that there was still a holdout in the person of Kentish Brock.

This gentleman, besides having important connections in Guernsey, was also an influential member of the Brock family.16 As such, his views held sway—and he was more than a little inclined to entertain Forster’s opinions. Miss FitzGibbon was not overly perturbed when she learned of this dissenter, as she still had the backing of both Miss Guille and Miss Tupper. These ladies were highly respected in Guernsey, and their approval of Miss Mickle’s miniature was sure to quash any interference on the part of Kentish Brock. And by the first week of July, even he was suddenly found to endorse Miss Mickle’s discovery.17 In relaying the good news to Miss Mickle, an overjoyed Miss FitzGibbon asked: “What do you think of that, my cat?”18 As Miss FitzGibbon would come to realize, however, Kentish Brock’s acceptance of the miniature did not lessen his appreciation for the artistic talent displayed in Forster’s artwork. He was toying with the idea of having a painting of Brock for Guernsey’s Royal Court House, and whether it was the profile portrait or the miniature that was replicated in oils, Kentish Brock was determined that Forster should be the one to do it.19

Not long after her breakfast intrigues, Miss FitzGibbon was back in London.20 Forster remained in Guernsey, lingering just long enough to finish his mysterious commission before heading off to Paris. It was a study for a portrait of Brock (fig. 16). He also made a nuisance of himself, just as Miss FitzGibbon had predicted.21 Based on his many years of experience as a portrait painter, Forster considered himself completely justified in voicing his concerns about certain aspects of the miniature—or, more precisely, the illustration reproduced in The Cabot Calendar (fig. 14). Most notably, he made an issue of the arch of the eyebrow and the shape of the nose, neither of which compared very favourably with the two profile portraits (figs 3, 4) in Guernsey.22 Forster’s pronouncements were damaging, but Miss FitzGibbon knew that they would have little bearing on the Brock relatives. However, she also knew that their favourable opinion would be no match for the States of Guernsey (the island’s parliament). Miss FitzGibbon had good reason to worry about the possibility of a political intervention. There were reports that Forster was offering to sell the States a portrait of Sir Isaac Brock, which was likely to be an elaboration on one of his copies of the profile portrait. Such a commission, she feared, would give him and the Robinsons “this card to defeat us.”23 Yet, Miss FitzGibbon was not quite ready to throw in her hand.

Figure 16.

Figure 14.

Figure 3.

Figure 4.

Encouraged by her visit to see Gerald S. Hayward, whose attitude towards the miniature was so utterly agreeable, Miss FitzGibbon became all the more intent on seeking out some further expert opinions in London. Two or three positive reports would be more than enough to neutralize Forster’s opposition, just in case his doubts regarding Miss Mickle’s discovery were ever given credence.24 If so, a forceful rebuttal could be quickly and easily deployed by way of the press.25 All it required was a careful comparison. Miss FitzGibbon was confident that the art experts would see an unmistakable resemblance between the sitter in the miniature and the profile portraits, despite what Forster had to say. To this end, she asked Miss Tupper to bring her both versions of the profile portrait (figs 3, 4). While Miss Tupper was happy to oblige, as she was going to London anyway, it would require considerable effort to negotiate the loan of these treasured heirlooms, and she simply could not fathom why two copies of the same portrait were required.26 They were virtually identical, and so Miss Tupper decided to ask for the loan of only one—which happened to be the copy (fig. 4), and the one that Forster used as the model for his own portrait of Brock.27

This new arrangement greatly displeased Miss FitzGibbon, as she expected Miss Tupper to do her bidding, and also because she believed that no self-respecting art expert would give her an opinion without seeing the original profile portrait (fig. 3). For this same reason, Miss FitzGibbon regretted not having the miniature (fig. 11), which remained back in Toronto with Miss Mickle.28 Clearly, her plans had not been fully developed when she set out for England and now the situation was becoming dire. But in giving the matter some further thought, she decided it might be possible to make do. After all, she still had her photographs of the miniature (figs 12, 17), as well as the copy made by Hayward (fig. 13), and before long she would also have the copy of the profile portrait (fig. 4). Therefore, a facial comparison was still feasible—even if the effort was becoming something of a struggle.

Figure 11.

Figure 12.

Figure 17.

Figure 13.

As much as Miss FitzGibbon wanted to participate in the miniature’s authentication, her resolve was severely tested by Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee and all the disruption that went along with it. Going in search of art experts was extremely difficult, and unsettled personal affairs caused additional stress.29 Along with worrying about an ailing sister back home in Canada, Miss FitzGibbon was also burdened with the responsibility of having to sell a family property in England.30 The pressure was intense, and a harsh criticism would prove to be last straw.

In mid-June of 1897, Miss FitzGibbon received a letter from Miss Mickle scolding her for having been in an “excited state,” presumably because she had been overly talkative with Major Holden. Losing her temper, Miss FitzGibbon angrily replied: “You have always, to judge by your letters, been in a more excited state than I have been over it, so do not throw stones—and do not waste postage, time and paper telling, nay urging me to do what I am doing to the best of my ability. I have given it the first place in time and thoughts, so do not scold any more. I have many other things to do and think of, and can only do the best I can.”31 More hurt than offended, Miss FitzGibbon made use of the same letter to make amends. “Now do not run away with the thought I have ever intended to give up,” she assured her dear “pardner.”32 There was no reason to let a slight misunderstanding come between them, and Miss FitzGibbon was sure everything would turn out right in the end.

Although the copy of the profile portrait had been available since the second week of June, the Queen’s Jubilee continued to complicate matters.33 A fatigued Miss FitzGibbon therefore decided to forgo her pursuit of art experts, but only long enough for a brief respite in Bristol.34 She hoped to find London back to normal by the time of her return a few days later. But much to her chagrin, there were still hordes of people everywhere she went. Compounding the problem was Miss FitzGibbon’s own growing sense of inadequacy, which found expression in her correspondence with Miss Mickle. “I have worried myself nearly into brain fever over my failure to do all you require,” she confessed. It was then that she explained: “I dare say all the anxiety and . . . other things coming all at once has left me more incapable than I otherwise might have been. I go over it again & again until I wish I had never come to England at all. I believe now we could have done better about it all by letter.”35 Miss FitzGibbon was beginning to doubt her ability to assist Miss Mickle, and in the process she became seriously depressed over it. Yet, she also had every reason to believe that the miniature could in fact be authenticated, and this belief helped to improve her disposition.

A re-invigorated Miss FitzGibbon was soon looking for guidance at George Rowney and Company, the world-famous artist supplies manufacturer.36 In speaking to one of Rowney’s sons, possibly Walter Rowney, she asked him if he knew of any artists who might offer their opinions on “vexed or unknown portraits.”37 Miss FitzGibbon elaborated by saying that she had two such portraits “purporting to be of the same person, one a profile, the other a full face,” and she wanted an expert opinion to confirm that they were one and the same. The response was unequivocal. Only a miniature painter could answer such a question, “as they knew the correct measurements by which to judge.”38 Miss FitzGibbon was then given the address of Frank Nowlan, a miniature painter in Soho Square who also specialized in the restoration of these diminutive portraits.39 But before she had a chance to see Nowlan, Miss FitzGibbon met up with Henry F. Rawstorne.

Figure 18.

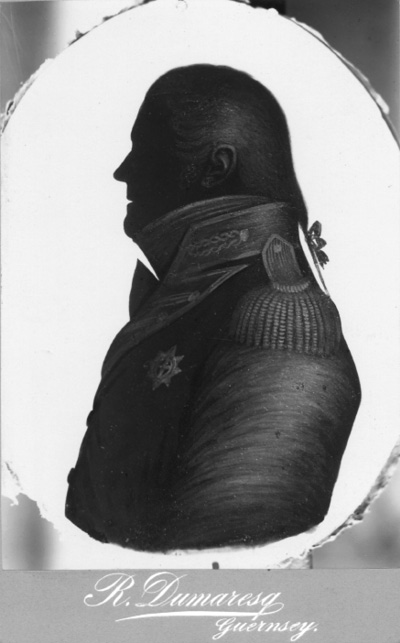

Rawstorne was a solicitor who also happened to be a friend of Lionel Cust, the director of the National Portrait Gallery.40 How Miss FitzGibbon became aware of Rawstorne is not known, but upon hearing of her interest in finding some art experts, he very kindly offered to invite Cust’s participation. Miss FitzGibbon accepted Rawstorne’s suggestion and gave him the pictures Cust would require to make a comparison. One of them was Baker’s photograph of the miniature discovered by Miss Mickle (fig. 17), but instead of the profile portrait supplied by Miss Tupper (fig. 4), Miss FitzGibbon substituted the proof print of a silhouette she had just received from Canada (fig. 18).41 It was only after Miss FitzGibbon set out for England that Miss Mickle obtained a photographic copy of this silhouette from Aemilius Jarvis, a prominent Toronto banker and financier. According to the story related by Jarvis, the silhouette came down through several generations of his family via his grandmother, Miss Mary Boyles Powell. She was the supposed fiancée of Lieutenant Colonel John Macdonell, who was Brock’s ill-fated provincial aide-de-camp.42 This provenance convinced Miss Mickle that the Jarvis silhouette was a reliable indicator of Brock’s profile, and that it would serve as an accurate gauge of her miniature’s authenticity. Just as Miss FitzGibbon advocated, a careful comparison was all it would take to settle the question. But in order to achieve a result that would silence the naysayers, the comparison had to be conducted by art experts of the type only to be found in London. Accordingly, Miss Mickle hastened to send off the proof print to England. The delivery was made just in a nick of time, and Miss Mickle took it for granted that Miss FitzGibbon would embrace this new approach to authenticating the miniature. But the awful truth soon became all too apparent: Miss FitzGibbon had an agenda of her own.

Regardless of the seemingly unassailable family traditions validating the Jarvis silhouette, Miss FitzGibbon was not entirely satisfied that it was actually Brock’s profile. But against her better judgement, she proceeded as per the new instructions from Miss Mickle, who made it abundantly clear that they had “no interest in proving Miss Tupper’s portrait.”43 Miss Mickle actually meant the profile portrait brought over from Guernsey by Miss Henrietta Tupper, which was the copy then belonging to John Savery Carey (fig. 4). In any case, now that Miss Mickle had the Jarvis silhouette, she wanted nothing to do with the portrait supplied by Miss Tupper—fearing that it might lead to some advantage for General Robinson. Miss FitzGibbon, however, was not prepared to abandon the profile portraits, as there was always the possibility that the art experts might refuse to consider the Jarvis silhouette for some unknown reason. If so, she wanted them to compare the copy of the profile portrait (fig. 4) with the miniature (fig. 11). That way, if the sitter proved to be the same in each case, then Miss Mickle would still have confirmation of her miniature’s authenticity—as the profile portrait was widely accepted to be the very image of Sir Isaac Brock.

At the National Portrait Gallery, Director Cust seemed to think that the photographs of Miss Mickle’s miniature (fig. 17) and the Jarvis silhouette (fig. 18) both featured the same man, but he was far too shrewd to put it in writing. Instead, he recommended that Miss FitzGibbon consult Algernon Graves, a print publisher who was known to have compiled a list of portrait painters from years past.44 Rawstorne took it upon himself to set up a meeting, and it was agreed that Graves would see Miss FitzGibbon the next day at five o’clock in the afternoon. The following morning, Miss FitzGibbon made good use of her free time by calling on Frank Nowlan, the miniature painter in Soho. She found him to be “a clever, keen-faced Irishman of about sixty in a dusty, rather crowded study—with lovely old furniture and a real art look about it.”45 Just as she had done for Cust, Miss FitzGibbon provided Nowlan with Baker’s photograph of the miniature and also the proof print of the Jarvis silhouette. Arranging them side-by-side, she asked Nowlan if he thought they portrayed the same man. After a careful study lasting some ten or fifteen minutes, Nowlan finally agreed. “Yes,” he said, “I have no hesitation in saying they are of the same man—the lock of hair over the forehead in the silhouette is the only doubtful point, but nose, eyes, eyebrows, mouth, chin are alike.”46 The silhouette (fig. 18) appeared to portray an older man with a full head of hair, while the miniature (fig. 17) featured a young man with a thinning hairline. Without labouring the point, Miss FitzGibbon asked Nowlan for his opinion in writing. The old artist complied, and for a small fee Miss FitzGibbon had the first of her expert opinions.47

Miss FitzGibbon then made her way to Pall Mall, where she hoped to get a second opinion from Algernon Graves. But this gentleman had to decline, as he did not consider himself qualified to judge likenesses. His interest was mainly historical, but he agreed to look through his lists for the obscure artist who signed his name to the miniature. Try as he might, Graves was unable to find any reference to a J. Hudson.48 When his pressing and persistent visitor happened to drop Gerald S. Hayward’s name, Graves finally saw an opportunity to be of assistance. “There you may get an opinion,” he replied. As was the case at Rowney’s, Graves advised that “a miniature painter would be the best to consult.”49 He then very graciously offered to escort Miss FitzGibbon to a nearby exhibition of miniatures, which had only recently opened, and where he thought she might find someone able to help. Thinking this an excellent idea, Miss FitzGibbon agreed to set out for the gallery hosting the Society of Miniature Painters.50 Upon entering, Graves introduced her to the secretary of the society who, after learning the nature of her request, advised that she speak to the president. As a miniature painter himself, that gentleman “could speak with [more] authority than any one else in the artist world of London.”51 Finding that Miss FitzGibbon was agreeable, the secretary began writing out a letter of introduction. Just then, however, two men walked into the gallery, one of whom happened to be Alyn Williams—the president who was just described to Miss FitzGibbon.52

When Williams offered to help the lady from Canada, Miss FitzGibbon produced Baker’s photograph of the miniature (fig. 17) and also the proof print of the Jarvis silhouette (fig.18). Although Williams expressed regret at not being able to see the originals, he was still willing to offer an opinion. Such a question as Miss FitzGibbon wished to have answered, he assured her, could be just “as readily if not better judged from a photograph than from the original or from a painting,” and this because “the photograph was sure to have the lines clear and correct.”53 When Williams questioned the silhouette for the same reason as Frank Nowlan, namely the protruding lock of hair over the sitter’s forehead, Miss FitzGibbon immediately offered up a photograph of the original profile portrait of Brock (fig. 3).54 She had been holding this forbidden likeness in reserve, waiting for just one more expert to question the Jarvis silhouette. And now, released from any further obligation to Miss Mickle, the real test could begin. After judging the resemblance between the profile portrait and the miniature, Williams gave his verdict. “Those two,” he declared, “are of the same man—there is no doubt whatever about it—but I should doubt the silhouette.”55

With two art experts casting doubt on the Jarvis silhouette (fig.18), it could hardly be regarded as an accurate gauge of the miniature’s authenticity. Miss FitzGibbon was not at all surprised. Yet, Frank Nowlan thought it bore some resemblance to the miniature discovered by Miss Mickle, and so too did Lionel Cust. But all that mattered was what Alyn Williams, in his capacity as president of the Society of Miniature Painters, had to say. And by thinking the likeness in the miniature (fig. 11) matched that of the original profile portrait (fig. 3), he provided the confirmation Miss FitzGibbon’s needed without having to resort to the Jarvis silhouette.56

Miss Mickle was not happy that her instructions had been blatantly disregarded, or that Williams had cast doubt on the Jarvis silhouette. Although his comparison actually served her purpose, Miss Mickle found his low opinion of silhouettes galling in the extreme. It was an inadvertent offence, and one Williams committed while examining the Jarvis silhouette for Miss FitzGibbon. Despite recognizing it to be the work of a professional, he recounted his experience that even the most skillfully cut silhouettes were often “quite unlike the man or face they are supposed to represent.”57 Miss Mickle, however, had no patience for Williams, or his “theories about the humbler sister art of silhouette-making.”58 She preferred to believe that the Jarvis silhouette was “surely a good one.” And given Miss Mickle’s unyieldingly attitude, it was just as well that Williams had his dealings with Miss FitzGibbon—as she was more favourably inclined to his opinion and therefore more susceptible to the salesmanship he was about to unleash on her.

Figure 19.

When Miss FitzGibbon asked Williams for a written statement of his opinion, he readily complied and she must have thought herself ahead of the game.59 But it was Williams who got the better of Miss FitzGibbon when he persuaded her to commission a copy of Brock’s profile portrait (fig. 19). What he proposed, in effect, was a copy of a copy—as the profile portrait brought to London by Miss Tupper was not the original. And while Miss Tupper may have been put to a lot of trouble for nothing, Williams was certainly able to profit by her inconvenience. Upon learning that the portrait was close at hand, he “advised a facsimile.” Miss FitzGibbon fell for the sales pitch, and as she reported back to Miss Mickle, “I see the advantage as it will confound the bad copyists.”60 Back in Canada, Miss Mickle was baffled as to which portrait Williams had copied, and in asking Miss FitzGibbon for a clarification, she was told in no uncertain terms that it was the original. “The other is the copy!”61

Unfortunately for Miss FitzGibbon, she had it backwards. The profile portrait borrowed from John Savery Carey (fig. 4) was generally thought to be a copy, as it was weaker in style.62 Miss Tupper and Mrs. Huyshe had concluded as much in 1881, and Miss FitzGibbon saw no reason to doubt them. That is, until Williams convinced her otherwise by declaring it to have been “done from life originally and by a good hand.”63 An artist of Williams’s stature was not likely to have ventured such an opinion without seeing the other portrait, had he known of its existence. But Miss FitzGibbon was rather selective in the material she presented to the art experts, and so Williams might have been unaware of the original profile portrait belonging to Henry Bingham de Vic Tupper (fig. 3). Whatever the case, Miss FitzGibbon went along with Williams and began treating the copy of Brock’s profile portrait as though it were the original. As far as she was concerned, the judgement of the president of the Society of Miniature Painters was incontrovertible (so long as it upheld Miss Mickle’s discovery). Miss Tupper, no doubt, would have disagreed with this revisionist approach had she any knowledge of it. But it appears that Miss FitzGibbon kept this new development to herself, and with some justification. Although Miss Tupper was an enthusiastic supporter of the newly discovered miniature of Brock (fig. 11), she also had an annoying habit of speaking her mind—as in the case of a certain bronzed silhouette.

What Miss Tupper called the “bronze profile” (fig. 8) was really just a silhouette with gold highlights. As for the sitter, he looked to be a heavy-set army officer with his hair tied back in a queue and a badge conspicuously displayed on his chest.64 Miss Tupper and her relatives treasured the bronze profile as a faithful likeness of Sir Isaac Brock. But when it was shown to Miss FitzGibbon, she was immediately suspicious. Privately, she expressed her belief that the officer portrayed “a very much older looking party” than Brock, who did not live beyond the age of forty-three.65 Moreover, there was also a problem with the insignia, which Miss FitzGibbon thought was meant to represent the Order of the Bath. She knew that Brock had been knighted, and furthermore that he was killed before the news could reach him. Consequently, it was impossible for him to have worn any such badge of honour. A confident Miss FitzGibbon summarily rejected the bronze profile by telling Miss Mickle: “I do not think it is Brock at all.”66

Figure 8.

It was obvious to Miss FitzGibbon that the bronze profile portrayed someone other than Sir Isaac Brock, and she probably should have been content in this knowledge. But curiosity got the better of her. In trying to account for the misidentification, she began to look upon the bronze profile as a “posthumous production.”67 A mourning keepsake also suggested itself, which led her to think that the bronze profile might have been inspired by the statue of Brock in his memorial at St. Paul’s Cathedral (fig. 20).68 But then she decided that the bronze profile must have been devised in advance of Brock’s memorial. This seemed a more plausible sequence, as it allowed for the bronze profile to have served as a guide in sculpting the hero’s face. Daniel de Lisle Brock was the logical choice for a model, since he was known to resemble his famous brother. Of course, it would have been more logical for the sculptor to work directly from a sitting with Daniel de Lisle Brock—except that it would have rendered the bronze profile unnecessary. It was a sticking point that apparently never occurred to Miss FitzGibbon, perhaps because she had become obsessed with the queue evident in the bronze profile. Although she seems to have known that this hair style was outdated by the time of Brock’s death in 1812, Miss FitzGibbon simply assumed that a queue was added to the bronze profile at some point—and for no better reason than Brock may have worn one during his last visit home in 1806.69 Miss FitzGibbon had a grand time letting her imagination run wild, but this much was certain: the bronze profile was not Brock. It must have come as quite a nasty surprise, however, when Miss Tupper steadfastly refused to agree.

Figure 20.

Miss Tupper had grown up believing that the bronze profile represented her famous great-uncle, and she would not be told otherwise—certainly not by an outsider who seemed to think that family traditions in Canada were more reliable than those in Guernsey. If the authenticity of the miniature discovered by Miss Mickle could rest on the Short family tradition, then there was no reason why Miss FitzGibbon should doubt the Tupper family tradition regarding the bronze profile. “No clue,” Miss Tupper urged, “is more to be relied on, than well authenticated and substantiated tradition coming down from those who knew the man.”70 Miss Tupper was uncompromising in her stance on the bronze profile, which left Miss FitzGibbon no choice but to acquiesce. The bronze profile was merely a side issue, and it certainly did not warrant an acrimonious debate, or the possible loss of Miss Tupper’s support for the miniature discovered by Miss Mickle.71 Still, Miss FitzGibbon must have thought it fortuitous that she decided to exclude Miss Tupper from her sessions with the art experts.72 She was simply too outspoken, and Miss FitzGibbon was not about to risk losing control of the proceedings. But with the miniature authenticated, Miss Tupper was less of a concern. Forster, however, still remained a threat.

By the second week of August, having finished attending to her personal affairs in England, Miss FitzGibbon was on her way home.73 In the meantime Forster had returned to Guernsey for the sole purpose of painting a larger portrait of Brock (fig. 21).74 And just as Miss FitzGibbon suspected, he was hoping to make a sale to the States of Guernsey.75 He was no doubt prodded by Kentish Brock, who Miss FitzGibbon mistakenly believed had been brought onside. As Forster recalled nearly thirty years later, he had only just completed his study when a deputation from the States: “waited upon me, and said they hoped that I would consent to the portrait I had made remaining on the Island, their belief being that his native home had first claim. I expressed appreciation of their desire, and said, ‘My country, Canada, claims Sir Isaac Brock as her particular hero, because his great master achievements for the defence of Canada and the Empire were performed within our borders. And as the portrait, if satisfactory, may be regarded as a commission from the Ontario Government, therefore this first portrait must go to Canada. I offered, however, to paint for Guernsey a portrait in larger half-length from the original material, which included authentic documents and data. The proposition was referred to the States and approved, and the resulting portrait of General Brock now hangs in the States [or Royal Court] House.”76 Actually, it was several members of the Royal Court who were “waited upon,” and by Kentish Brock. His purpose was to determine if they might be interested in purchasing Forster’s study (fig. 16), but it was thought too small and so the offer was declined. It was only then that Forster suggested a larger portrait, although Kentish Brock claimed it was he who proposed the enlargement.77

Figure 21.

Forster definitely preferred his own view of the past, probably because the impression of an unsolicited interest in his work was a far greater testament to his talent. The artist as patriot was another concept that appealed to Forster’s rather inflated ego, which demanded nothing less than a legacy of unanimous approval for his new portrait of Brock. It is no wonder, then, that Forster left the world a record of himself designed to perpetuate the myth of his own importance. His was a grand deceit, which might never have come to light . . . had it not been for a debate by the States of Guernsey.

On the first day of September 1897, some two weeks after Forster arrived back in Toronto, the States met to deliberate a number of different proposals, including his offer to sell them a portrait of Sir Isaac Brock.78 Under consideration was whether or not to vote £40 for the purchase of the smaller portrait (fig. 16), or £60 for the larger one (fig. 21). The debate really centred on the deluxe canvas, however—it having already been decided that a larger portrait would be more suitable for display in the Royal Court House. The president of the States, Bailiff T. Godfrey Carey, was not averse to the idea of a memorial to Brock in the form of a portrait, and in his opening remarks he emphasized the significance of such an undertaking: “We ought to be proud of Sir Isaac Brock, a compatriot who has so distinguished himself.” Then the bailiff asked: “Should we not seize this opportunity of perpetuating his memory by placing his portrait in the Royal Court?” There were already several memorials to Brock, especially in Canada, and “there ought to be one in Guernsey.” It seemed the bailiff was ready to support the purchase, but then he did an about-face. Not convinced that Forster was the best artist for such an important commission, Bailiff Carey cautioned the assembled deputies, jurats, and rectors. Before casting their votes, they first had to ask themselves: “Is the portrait good enough?”79

The bailiff’s warning was due in large measure to the meddling of Miss FitzGibbon. During her short stay in Guernsey, she did her level best to defame Forster’s reputation as an artist.80 But Miss FitzGibbon’s greatest meddling involved a lady who was introduced to her as Mrs. Nathaniel Stevenson, the wife of Guernsey’s lieutenant governor.81 When Mrs. Stevenson casually asked about the level of esteem for Forster’s artwork in Canada, Miss FitzGibbon found herself momentarily at a loss for words. But her awkward hesitation seemed to have the desired effect, as she later heard it said that Forster failed to sell the States his study for Brock’s portrait because the lieutenant governor would not consent to its purchase.82 However, Miss FitzGibbon’s informant was seriously mistaken as to the extent of viceregal influence over the States. While Lieutenant Governor Stevenson held an exalted position as the Queen’s representative in Guernsey, he possessed no legislative authority. Even if Mrs. Stevenson had induced her husband into believing that Forster’s work was inadequate, the lieutenant governor could not have interfered with the purchase of the study. Nor is there any evidence to suggest that he had any intention of doing so. Granted, the lieutenant governor may have thought the study too small, but it does not appear that he went so far as to publicly voice his disapproval of Forster’s work.83 Bailiff Carey, however, had no such qualms—and he had no hesitation in expressing his reservations about the calibre of Forster’s artistic abilities.

Kentish Brock reacted by providing the bailiff with a list of the eminent Canadians whose portraits had been painted by Forster.84 But despite this attempt to reverse the damage done by Miss FitzGibbon, the bailiff remained skeptical. Unable to challenge Forster’s popularity in Canada, the bailiff turned his attention to the original likeness of Brock by questioning its authenticity. He made enquiries of Miss Tupper, who asserted that the copy of Brock’s profile portrait (fig. 4), which Forster used for his own rendition, as well as the original (fig. 3), “have been always known in the family as Sir Isaac.”85 Thwarted once again, the bailiff decided that the best way to sabotage the purchase of Forster’s painting was to question his artistic merit at a meeting of the States. By planting the seed of doubt in his opening remarks, the bailiff hoped his fellow members would decide on their own that Forster’s portrait of Brock was not “good enough” for the Royal Court.

The debate began with another Carey addressing the cost of the larger painting (fig. 21). In keeping with a Guernseyman’s high regard for economy, Deputy William Carey argued that “it was essential to get proper value for one’s money.” He then proceeded to read a letter from a well-known artist, who stated his belief that the States “would have a good bargain at £60.”86 Based on this recommendation, Deputy Carey thought the “picture did great credit to Mr. Forster, the artist.” The Very Reverend Thomas Bell was not so sure. He thought it advisable to send the matter to committee and wait for a report.87 But before his fellow members of the States had a chance to weigh the pros and cons of such a motion, the proceedings were upset by yet another Carey.

Jurat De Vic F. Carey was a retired major general in the British army, and one who now took on the additional role of art critic. As he bluntly pointed out: “Sir Isaac Brock is represented with a neck large enough for two.”88 This was not the portrait’s only flaw. Brock appeared to be about six inches too short. His head was too big and not properly positioned. The right arm was not long enough, and it was also badly painted—as were the hands. As for the uniform, it was all wrong. Jurat Carey spoke with confidence, as he “was backed up” in what he had to say. But notwithstanding his severe critique, there was soon a more balanced view of Forster’s work.89

Figure 22.

Jurat Jean T.R. de Havilland suggested that perhaps “the faults might have been in the original [portrait].” Deputy James Le Page agreed, adding that “Sir Isaac Brock might have looked just as he is depicted, in which case the artist had only done his duty in representing him with all the deformities mentioned.” Forster’s support continued to grow, with several of the members echoing Rev. Bell’s call for a committee. Bailiff Carey, however, thought they should simply choose an expert to decide, “as people differ in questions of art.” But when Deputy Edouard Valpied alerted the assembly that such an “expert would charge a fair [or high] price for his opinion,” the debate suddenly became rather subdued. It was then that the cost-conscious Deputy Carey warned the States about discussions on art, and how they “never came to an end.” Faced with this frightening prospect, Jurat Jean Tardif proclaimed Forster to be a competent man, and so “there was no need to go further for an opinion.”90 The amendment for a committee was then withdrawn and the question put to a vote, which was carried by an “overwhelming majority” in favour of purchasing Forster’s larger portrait of Brock.91 The deed was done.

Despite the best efforts of Miss FitzGibbon and Bailiff Carey, Forster was still able to make a lucrative sale to the States of Guernsey. With it came the formal recognition that threatened to mitigate Miss Mickle’s discovery. Yet, this advantage was never put to good use. Like General Robinson, Forster was leery of controversies. They were bad for business, and he was not about to alienate customers who might be interested in his line of Brock portraits. There was only one such sale, however, and that was to the Government of Ontario in 1900 (fig. 22).92 As for the Robinsons, they finally decided to call off their crusade against the miniature (fig. 11)—mainly because the painting by George Berthon (fig. 9) was still recognized as the official portrait of Sir Isaac Brock.93 And while Miss Mickle was never rewarded with great fame or fortune for her discovery, both she and Miss FitzGibbon derived great satisfaction from the miniature’s acceptance as authentic and also in having browbeat their opponents—with the exception of one who was yet to be born.