Chapter 7

Construction Begins

1849

In August 1849, while the surveys were still underway, the company advertised in newspapers for construction bids. Under the heading “Notice to Rail-Road Contractors!” it stated that the Milwaukee, Waukesha, and Mississippi River Railroad Company was receiving sealed proposals for grading, bridging, and laying of the railroad's superstructure (the ties and rails). Yet in mid September the company found it had sold subscriptions to only four hundred thousand dollars' worth of its stock—one hundred thousand dollars short of what was called for to begin construction. With winter fast approaching, the directors feared further delay. They proceeded to let the contracts despite the shortfall.

The directors had several choices for how to go about building the railroad. They could simply hire laborers and direct them; they could allow the owners of the road—the stockholders—to build the road; or they could hire contractors with the needed men and tools to do the job. Although the latter option was the most common for large construction projects such as railroads or canals, the directors of the Milwaukee and Waukesha Railroad chose a mixture of the last two methods. They divided the twenty and one half mile route into thirty-four sections, each of which could be bid and contracted for separately. The contracts specified grubbing (removing trees and roots), grading (building the roadbed), ballasting (topping with gravel), laying culverts to allow drainage, and building bridges. The sections nearest Waukesha were reserved for the stockholders, while the rest were to be bid by contractors.

Sales of stock subscriptions became robust as bids for construction were about to be let. On September 24 the Daily Wisconsin noted that Byron Kilbourn was promoting a new strategy. We learn from the Rock County Badger that on September 17

a large meeting was held … to listen to an address from Mr. Kilbourn. … He propose [d] that farmers who choose [buy stock] … should contribute stock in labor of grading the road. The idea of people building their own Railroads is an excellent one.1

The contracts for grading were let on September 28 at Waukesha, each having been awarded to the lowest bidder. The contract amounts varied. The lowest was for $614, and the highest was $3,029. They totaled $44,374, which was slightly lower than the estimated cost of building the road. While some contractors may have underbid, the directors maintained that all of the contractors would make a healthy profit.2 The November 28 Milwaukee Sentinel reported:

We also learn that Mr. Clinton, acting under the instructions of the Board, has let a number of contracts for clearing and grading the line of the road at prices very much below the estimated cost of such work. These contracts have been let to Farmers along the line who propose to work out their subscriptions in this way. It is gratifying to know that the people of the interior evince the most lively interest in the success of this great enterprise.3

One week later, the Watertown Chronicle reported:

Milwaukee and Waukesha Railroad—Contracts for the grubbing and grading of the road were let last week. We understand that M. L. O'Conner, Esq., the enterprising plank road contractor, was the successful bidder for 13 sections, or some six or seven miles—the heaviest of the contracts. He is an engine of himself, and if supplied with the motive power, will be sure to “go ahead.”4

Construction began in October. Contractors and their crews, farmers along the line, stockholders, and anyone else wishing to lend a hand pitched in. Surveyors had marked the line with wooden stakes. The first job was clearing the line-removing brush and felling trees. Next came the work of grubbing—removing the roots and stumps from the roadway. The most stubborn roots were those of the prairie oaks, the roots of which had grown deeper over many years while prairie fires repeatedly burnt off the tops.

Grubbing was made easier by the use of a plow. A breaking plow pulled by ten yoke of oxen was ideal, but more common was a plow pulled by one or two oxen that would stop whenever it struck a large root. When that happened, the grubbers had to remove the root by hand. When possible, work on culverts and bridges was begun early. This was so that the grading would properly line up with them. Grading was the main work. With picks, shovels, wheelbarrows, horses, oxen, and plows, men moved dirt and built up the roadbed. On level ground they would simply dig the drainage ditches that were necessary on either side of the roadbed, casting the dirt to the middle. A head grader would stand on the grade and indicate with his shovel where the next shovelful should land to keep the grade even. Where there were hills and valleys, the work was far more difficult. The hills would be dug through to make the “cut” for the roadway, and the dirt and gravel removed from the cut would be dumped to build up the embankments over the adjacent valleys. Ideally, the amount of dirt from the cut was exactly what was needed to level out the course, but more often than not extra dirt would have to be brought in. The final step in the grading process was applying gravel, which was brought in on wagons. Gravel gave the road stability and good drainage. It was found in abundance along the first division between Milwaukee and Waukesha, and the men were instructed to apply it generously, to a depth of two feet.

The first section—just next to the station grounds in Milwaukee and along the Menomonee River—was one of the more difficult. Menomonee means “wild rice,” a plant that grows in water—and much of the line here was in fact being built on land that was under water, up to two to six feet deep in some places. Across the river was a bluff on which men loosened the dirt with picks and shovels and loaded it into dumpcarts. Teamsters would then take the carts across the river, then to the end of the grade, where they would dump the load. As the bluff became lower, the grade became longer—where there had been water, there was now a roadway. Many of the men employed as graders had done similar work cutting down the bluffs and filling swamps to build the city of Milwaukee.5

Edward D. Holton, in an 1858 address, recalled the initial building of the roadbed, noting the “sober earnest purpose” of those involved and the common practice of paying for subscriptions in goods or labor:

It was a great undertaking for that day, under the circumstances. We were without money as a people, either in city or country. Every man had come to the country with limited means—and each had his house, his store, his shop, his barn to build, his land to clear and fence, and how could he spare anything from his own individual necessities? Some wise men looked on and shook their heads, and there were many croakers. But in the minds of those who had assumed the undertaking, there was a sober earnest purpose to do what they could for its accomplishment. It was demanded of our own people that they should lay aside all their feuds and personalities, and one and all join in the great work. To a very great extent this demand was complied with, and gentlemen were brought to work cordially and harmoniously together who had stood aloof from each other for years. The spirit of union, harmony and concord exhibited by the people of the city was most cordially reciprocated by those of the country along the contemplated line of road. Subscription books were widely circulated, and the aggregate sum subscribed was very considerable. I said we had no money, but we had things, and subscriptions were received with the understanding that they could be paid in such commodities as could be turned into the work of constructing the road. This method of building a railroad would be smiled at now, and was, by some among us, then. But it was, after all, a great source of our strength and of our success; at any rate, for the time being.

The work was commenced in the fall of 1849, and for one entire year the grading was prosecuted and paid for by orders drawn upon the merchants, payable in goods—by carts from wagon makers, by harnesses from harness makers, by cattle, horses, beef, pork, oats, corn, potatoes and flour from the farmers, all received on account of stock subscriptions, and turned over to the contractors in payment of work done upon the road. A large amount of the grading of the road from here to Waukesha was performed in this way. Upon seeing this work go on, the people began to say everywhere—why, there is to be a railroad, surely, and the work rose into consequence and public confidence.6

Indeed, public confidence not only bolstered spirits, but padded the subscription books, ensuring that the difficult work of grubbing, grading, and building bridges and culverts could keep on. On October 16 the editor of the Waukesha Democrat reported:

Operations have commenced on this end of the line in good earnest. The foundation for the depot at this place was laid up last week, and the superstructure will be pushed forward without delay, and covered in this fall. The grading on this end will be commenced in a short time.7

The editor then proceeded with uncanny accuracy to recommend lines that would eventually be built (this before a single rail had been laid in Wisconsin):

Complete your road to the Mississippi, and you secure the trade and mineral of the central and western counties. Start from your angle north of this place [Brookfield] running northwest, and tap the heart of the Fox River Improvement [Portage], from thence on through the now howling wilderness to the Capital of Minnesota, with your iron road, and Milwaukee controls the trade of the whole Northwest, Minnesota included. With a line to Chicago, Milwaukee has all the railroads she needs. Plank roads will do the rest. Ten years will see these suggestions in process of fulfillment.8

On October 23, the Waukesha Democrat followed up on their earlier article, reporting on the steady output of labor:

The work too, under contract, goes on steadily. The fine Stone Depot at Waukesha is rising apace. The grading on several of the sections between this city and that town is under good head-way We see no reason indeed to doubt that a year hence the trains will be running regularly twice a day between Milwaukee and Waukesha.9

The dimensions of this early work on the Milwaukee and Waukesha Railroad are apparent in this article from the Milwaukee Sentinel of December 18:

Our Rail Road—Between four and five hundred men are at work on the different sections of the Milwaukee and Waukesha Rail Road. The Directors are pushing ahead as vigorously as possible, and if backed up, as we doubt not they will be, by the stockholders, are bound to have the road finished and in operation to Waukesha next Summer.10

In the same paper, a weather report followed describing the conditions under which the men were working—not cold enough to merit a work stoppage, but cold enough to make for a great deal of discomfort:

A Cold Snap—The weather changed suddenly from moderate to very cold Sunday night, and at 8 A.M. yesterday, the Mercury was within one degree of zero.11

Kilbourn's railroad stock promotions had gained ground very quickly, with farmers buying labor subscriptions in droves. The October 31 Milwaukee Sentinel reported that:

The Farmers along the line of the Milwaukee and Mississippi Rail Road are subscribing liberally to the Stock. In the five towns of Whitewater, Waukesha, Palmyra, Genesee and Eagle, these subscriptions exceed $260,000. This amount, added to the sums previously subscribed, including the City subscription of $100,000, swells the aggregate to near $420,000. For a beginning this is indeed promising, and the ball will be “kept in motion.”12

The trend continued through the fall, as reported by the Milwaukee Sentinel and Gazette:

November 17

At a meeting of the directors … on the 14th … it is expected by the close of the week … the books … to be returned with … a sum total of Half-A-Million of dollars, including the City Subscription . . James Kneeland, Secretary Pro-tem.13

November 28. Our Railroad to the Mississippi—We learn from Mr. E. D. Clinton, one of the Directors of the Milwaukee and Mississippi Rail Road Company, that he has obtained within the last fortnight subscriptions to the amount of seventy nine thousand nine hundred dollars in the single town of Milton, Rock County. Most of the subscribers are Farmers, who take from $500 to $1,500 worth of stock in the road. The aggregate subscriptions, and all among our own people, to this great State enterprise, now amount to five hundred and sixty thousand dollars. This is, indeed, encouraging progress, and makes the eventual success of the undertaking more and more certain. It is worth while to state in this connection, that according to the Chicago Journal of Monday last, the whole amount subscribed to the Chicago and Galena R.R. Company thus far is but $350,000, nearly $200,000 short of the sum subscribed to the Milwaukee and Mississippi Road.14

In October two locating parties were sent to explore the country west of Waukesha ahead of the more detailed surveys that would take place the following spring. They found the country generally favorable for railroad construction, although the section through the Scoopenong Bluffs, between Eagle and Palmyra, appeared formidable. They ran their lines west to the railroad's anticipated crossing point over the Rock River (near present day Edgerton). Then they continued two miles further to the village of Fulton, where the line would go northward to Madison ascending alongside the Catfish (Yahara) River. At this point one of the parties proceeded to survey a branch route between Milton and Janesville. The directors at this early date had thought this branch important, though it was not in the scope of the company's charter. In December the weather took a turn for the worse, and the men decided to return to Milwaukee.15

One surveyor, twenty-eight-year-old Anson Buttles, had something more on his mind than his fellow workers. The year before, the Jacob Mullie family had arrived in Milwaukee, having come all the way from Holland. The fact that Mr. Mullie's daughter, Cornelia, spoke little English had not prevented young Anson from making her acquaintance. Because Anson was away on the job much of the time, he and Cornelia corresponded. In a letter dated December 4, he wrote:

Dearest Cornelia.

We are very busy now, indeed we shall have to work on next Sunday and every day next week and this week too, all the time, just as hard as we can. One of our men has left, and he was a good one, and I will have to work the harder for it … but you know, dear girl, that I must attend to my business… . I have thought that when Mr. Kilbourn came back I would get some money from him and we would get married now.16

Apparently, the railroad was laying ground for more than just a train route, at least for one young couple.

The First Annual Report of the Directors of the Milwaukee, Waukesha, and Mississippi Rail-Road Company, to the Stock-holders, issued on the last day of the year, was the first such report in Wisconsin. In it the directors expressed their pleasure in the progress made during 1849, especially with stock subscriptions, which had exceeded six hundred thousand dollars. They predicted that these would reach the one million dollar mark by April, at which time they would no longer solicit them, having gained

the full amount which the board deem it advisable to receive; and when this amount shall have been subscribed, the books will be finally closed, and no further subscriptions will be received. With this amount and a sound system of finance. the entire road can be completed without any further direct contributions of the stockholders.17

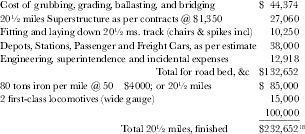

The directors also used the annual report to state the estimated costs of building and equipping the road to Waukesha, “based on actual contract prices … and on actual proposals for iron by the most responsible parties”:

The numbers were reassuring. They showed the cost to be $11,348.88 per mile—less than that of most other railroads (New England railroads averaged $39,000 per mile at this time, and other Western railroads as much as $30,000 per mile).19 One might wonder, however, whether the directors lowered estimates to make buying railroad stock more attractive.

For rails, the directors decided

to adopt the best and most approved style of H rail (commonly called T rail) at the outset of this work, and also the wide gauge of six feet (being the same as that adopted by the New York and Erie Rail Road Company), as being far superior to the narrow gauge in general use on most of the eastern roads—For high speed, and for long heavy trains with produce, and for general transportation, it is found that such a road possesses many and decided advantages over the ordinary road.20

The “H” or “T” rail chosen was similar to what we see on railroads today, but smaller and lighter. The gauge (distance between the rails) of six feet was new and popular at this time. The directors would, fortunately, change their minds and have the track built in “English,” or “standard” gauge (four feet, eight and a half inches), which is still commonly used today. Virtually all broad gauge railroads of the time—including New York's Erie Railroad—would eventually convert to standard gauge, and the conversion was expensive. It involved narrowing the track, rebuilding the trucks on all the cars to bring the wheels closer together, and rebuilding or retiring locomotives.

The directors went on in their report to estimate dates of completion for the first division between Milwaukee and Waukesha, predicting that the railroad would be completed by August 1850:

Grading and bridging will be completed … middle of June. By the time that iron can be shipped up the Lakes in the Spring, the road bed and superstructure will be ready to receive it… . It is expected to complete this division of the road within the month of August next.21

Then the directors let the proverbial “other shoe” drop—they informed the stockholders that they (the directors) had put the railroad up as collateral for a loan. Before divulging this fact, they made a case for what they saw as the necessity of doing so:

[N]egotiations have been opened with … iron manufacturers … and … proposals of the most favorable character have been received… . But to obtain this … it is necessary to go into the market with cash… . To draw upon the stockholders … would … be burthensome. About four-fifths … are farmers…Owing to the general failure of the wheat crop … there is a … pressure … which would render it impolitic to make … draughts … until they shall have … another crop. But in order to subserve those interests … with this improvement (the railroad), it ought to be completed, and in use, before the maturity of that other crop… . To effect this, resort must be had to a loan, based on the general credit of the Company, and a pledge of the road and its resources.22

Despite the directors' arguments, such a loan was not a necessity at that time. In Illinois, the Galena and Chicago Union Railroad had been building without needing to resort to borrowing. Possibly the Milwaukee and Waukesha's directors wanted to catch up with the Galena in the race to the Rock River valley. If so, such a loan would help.

The directors concluded their report by restating their maxim, that the railroad should be owned and controlled by the people of Wisconsin. And they reminded their readers that this would only be possible if they bought more company stock.

The year 1849 had been eventful in other ways. In March, Zachary Taylor, who had been the commandant at Fort Crawford on the Mississippi near Prairie du Chien, became the twelfth president of the United States. In April, Don A. J. Upham, a supporter of the Milwaukee and Waukesha Railroad, became the third mayor of Milwaukee. In November, Nelson Dewey, first governor of the state of Wisconsin, was elected to a second term.

With the discovery of gold in California, that state was in the news almost daily, and many Wisconsin residents decided to relocate there. The admission of California to the union, and whether it would be a slave state or free, was being hotly debated in the Senate.

Cholera had arrived in Milwaukee in July. It killed its victims quickly, often within a day, and one out of every two people infected died of the disease. It was spread by contaminated food and water, but this was not common knowledge at the time. Newspaper editors trod a fine line between warning readers and down-playing the disease because it was bad for business. A note by the editor of the Waukesha Democrat from July 31 was typical:

Three or four deaths from Cholera occurred in this village and nearby during the past week. At present we believe there is no symptom of the disease manifest in our midst, and it is to be hoped that this dreaded plague is no longer hanging over us… . A cheerful spirit, with quietness, temperance, and cleanliness, is the safest and best precaution.23

By September, 105 deaths had been reported, though the actual total was higher. Then, mercifully, cold weather ended the plague.24

On Thanksgiving Day there had been a run on Milwaukee and Waukesha Railroad director Alexander Mitchell's Wisconsin Marine and Fire Insurance Company to redeem deposit certificates for gold. For two days Mitchell and his associates took in certificates and paid out gold. When the public realized the company was not going to go under, it brought back the gold and received new certificates. As a result, the company acquired an even greater reputation for dependability, as well as more customers.25

In other railroad events, the Galena and Chicago Union Railroad in Illinois had 21 miles of road in operation with two daily trains in each direction. The Galena was to connect Chicago with the Mississippi and was seen by many in Wisconsin as an indicator of what the Milwaukee and Waukesha Railroad might do. Nationally, at the end of 1849 there were some seven thousand miles of railroad, all east of the Mississippi. The dream of a transcontinental railroad continued to gain traction. Asa Whitney had issued a booklet entitled “Project for a Railroad to the Pacific” that included a map depicting a railroad from Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin, to Puget Sound. A bill for a land grant for this road was to be brought before Congress. In Wisconsin, it was hoped that the Milwaukee and Waukesha Railroad might become a feeder to this line.

In October a “Pacific Railroad Convention” was held in St. Louis, Missouri. Milwaukee's Board of Trade sent Kilbourn, Holton, Osgood Putnam, and George H. Walker as delegates.26 They of course favored a northern route to the Pacific. The Milwaukee Sentinel of October 19 addressed the issue:

It will be found necessary … to carry the line … much farther north … in order to avoid the numerous streams subject to heavy floods and therefore difficult and expensive to bridge, which are to be found lower down… . The Mississippi terminus would have to be as far North as Prairie du Chien.27

Meanwhile, work on the shortest of transcontinental lines, the Panama Railroad, had been put under contract by the Panama Rail Road Company of New York, which had purchased exclusive building rights from the government of New Grenada (today's Columbia and Panama).

With events such as these capturing the nation's attention, one might think that the people of Wisconsin would deem the grading of a twenty-mile roadbed insignificant. They did not. Most of them had left their lives and loved ones in the East or in Europe to come to Wisconsin to forge a better life. The railroad promised to help them do this. It promised to make scarce goods abundant, to make the unaffordable affordable, and to transform some of life's drudgery into free time. It would allow them to visit friends and family in the East. This twenty-mile roadbed, now covered by snow, was solid evidence that those promises would be kept.