Chapter 19

Reaching the Mississippi

1857

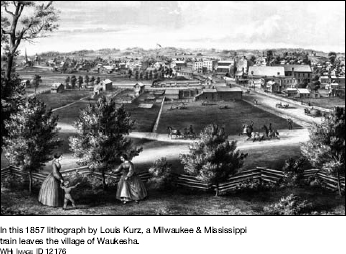

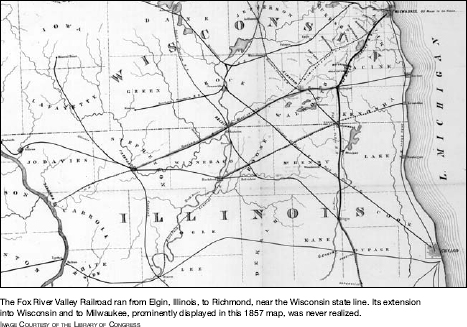

With only twenty-two miles of track left to lay, the Milwaukee & Mississippi Railroad was within spitting distance of a dream that had beguiled railroad promoters for almost a quarter of a century-completing a line connecting Lake Michigan to the Mississippi River. Unfortunately for the Milwaukee & Mississippi, its competitor, the La Crosse & Milwaukee Railroad, was about to complete its own line to the Mississippi at La Crosse. And as though that were not enough, railroad companies originating in the Lake Michigan ports of Sheboygan, Manitowoc, Racine, and Kenosha were featuring the Mississippi in their corporate names and building with the Mississippi as their goal. It appeared as though there would soon be many railroads traversing the state. Too many, perhaps. Yet some people sensed that the bottom was about to fall out from under the railroad boom due to the shaky financing and overly hasty expansion that many companies had believed was necessary in order to stay ahead of the competition. Few people had forgotten how twenty years before, during the panic of 1837, excessive borrowing had led to bankruptcy. Milwaukee & Mississippi President John Catlin certainly had not. He had bought the bonds rather than the stock of his company, becoming its lender. Yet the four-thousand-odd Wisconsin farmers who had mortgaged their farms to invest in railroad stock continued to be at risk, with some four million of their dollars at stake.1 If the railroads failed to pay the interest on their loans, those farmers were likely to lose their farms to the creditors.

In February a writer who signed himself “a Badger” wrote the editor of the Milwaukee Sentinel saying, “The thing is being overdone, and the moment confidence begins to fall, the whole fabric of our Rail Road system collapses.”2 A law enacted earlier in the year seemed to catch the metaphoric significance of such fear. It required all railroad crossings post warning signs with the words “LOOK OUT FOR THE CARS.” Locomotives in cities were now expected to ring their bells before crossing streets and to limit their speed to “six miles an hour-no faster.”3

In May a recession began that looked to last more than the remainder of the year. The bank panic that followed in August had repercussions for the railways that would soon change the course of the long railway boom in Wisconsin. In September, Karl Schurz, a German immigrant who had invested in real estate in Watertown, wrote, “Business is very quiet; money matters in the whole United States are depressed…. How far the financial crisis which has recently broken upon us may go is still hard to determine.”4 Sadly, in Wisconsin, it would go far, and one of its chief victims would be the railroads.

The first half of 1857 was marked by growth and mergers. The Kenosha and Beloit Railroad had two miles of track out of Kenosha and a new destination- Rockford, Illinois. The company's crews had worked through the winter; the men had been forced to break up the frozen ground by driving wedges into it. In Bristol Township a Mr. John Lavell was engaged in this work when the bank of earth on which he was standing collapsed, killing him-a rare accident that reminded all involved of the dangers of railroad construction.

During the early months of 1857 the railroad went through a series of rapid mergers and name changes. On January 20 the Kenosha & Rockford Railroad Company of Illinois was chartered and authorized to build between Rockford and an undetermined connection with the Kenosha and Beloit on the state line. Eight days later the Rockford and Mississippi Rail Road Company of Illinois was chartered to build from Rockford west to the Mississippi. On February 14 Wisconsin's Kenosha and Beloit changed its name to the Kenosha & Rockford Railroad Company. On March 5 it merged with the Kenosha & Rockford of Illinois to become the Kenosha, Rockford & Rock Island Railroad Company, chartered respectively as such in the two states.

The Wisconsin Central Railroad was also looking forward to expansion. On March 2 it had its charter amended, allowing it to extend its line from Portage to Lake Superior. That month also saw President Le Grand Rockwell replaced by Rufus Cheney of Whitewater.5

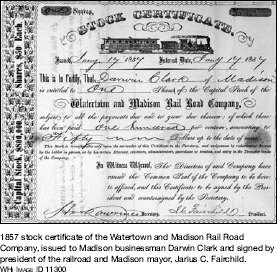

The Watertown and Madison Railroad Company was also optimistic. In January it received a one hundred thousand dollar loan from the city of Madison. Supporters of the loan maintained that a second railroad for Madison would reduce freight and passenger bills, raise property values, and reduce the cost of living in that city. Watertown and Madison President Jarius Fairchild and former governor Leonard Farwell went to the East coast with the bonds and came back with cash. Meanwhile, company stock agents were taking mortgages on Madison properties, to a total of ninety thousand dollars, for stock. Farwell mortgaged twenty-five thousand dollars' worth of his own property to buy stock.6 The railroad was to use East Mifflin Street coming into town, then swing south and cross the isthmus along the Lake Monona shore, and proceed to a depot on Murray Street west of downtown. On December 1 the Watertown and Madison Railroad Company executed a mortgage of its entire line, from Watertown to Waterloo, to Edwin Ludlow, trustee, to secure $340,000 of ten-year, 8 percent bonds. The company had been grading at both ends of its line and had laid track, completing twenty-four miles of its road, from Watertown to Waterloo.7

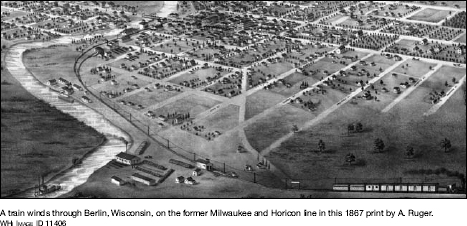

Other railroads also seemed to be thriving. That spring the Racine and Mississippi Railroad Company experienced a brisk business as Beloit shippers sent produce and wares over the new line to Lake Michigan. Meanwhile the company's rails entered Illinois just a few hundred feet beyond its Beloit depot. Rails were laid to Rockton and to Durand in May. By April another railway company, the Milwaukee and Horicon, had extended its line twelve miles beyond Ripon to Berlin, just forty-two miles from Milwaukee. The directors called for further expansion by extending the road to Stevens Point and Lake Superior. They ordered a survey and sent stock agents to solicit additional subscriptions along the proposed extension. The city of Milwaukee supported them. In April Milwaukee Mayor James B. Cross, addressing the common council, praised the plan:

This road seems destined to take a high rank among the railroad enterprises of this State; and will need no other than its own resources, to push it forward to Stevens Point, and from thence to Lake Superior. The farmers along this line, fully appreciating its importance, have stepped forward with commendable zeal and energy, and are daily furnishing available securities and means to push it onward to completion.8

In May, Luther Beecher, the Mineral Point Railroad's contractor, obtained ownership of the majority of the company's stock, giving him complete control of the company and allowing him to appoint a board of directors that then voted him in as president. Then, with the line between Warren and Darlington in operation and the tracks approaching Mineral Point, the company's supply of rails gave out. On May 13 the Monroe Sentinel reported:

Our Mineral Point friends complain of very dull times and are anxiously waiting for completion of the road, now within two and a half miles, but delayed for the want of iron, that is expected soon.9

Meanwhile, building contractors completed the Mineral Point depot, a thirty by fifty foot structure of native buff limestone, an engine house, and a 2,400 square foot machine shop, the latter two buildings also made of stone. Thankfully the rail shortage did not last, and in early June the Mineral Point Railroad was able to complete its thirty-two-mile line at Mineral Point. The fenced-in line had eight wooden bridges and forty-three culverts. On June 16 the first train left Warren, Illinois, and worked its way up the Pecatonica valley to Mineral Point. Two weeks later the Mineral Point Tribune found that

the business of the Mineral Point Railroad exceeds the expectations of most of our citizens…. We were at the depot on Friday last about the time the train was leaving and saw it start out with seven freight cars well filled, three loaded with wheat, three with lead, and one with sundries.10

The company had three locomotives-the John C. Freemont, the Mineral Point, and the Warren-and forty freight cars. In July the company ran several special trains to celebrate the opening of the line. The directors imposed a speed limit of sixteen miles per hour for all trains.

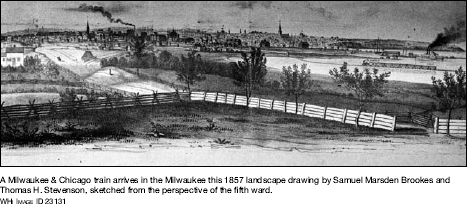

That summer the Green Bay, Milwaukee & Chicago shortened its name to the Milwaukee & Chicago. It opened a new station in Milwaukee by the lake at the end of Elizabeth Street (National Avenue), which became the new northern terminal of the line. To reach it, trains coming from Chicago had to pass over the marshes of south Milwaukee on a long wooden trestle. The company also kept its Bay View station, where it erected a roundhouse and freight facilities.11

The success and growth of the first part of the year culminated in the achievement of a dream long held by Wisconsin citizens and railroad pioneers: by March, completion of a line between Lake Michigan and the Mississippi was imminent. The Milwaukee & Mississippi had resumed laying track at Boscobel, only twenty-two miles from Prairie du Chien. With the Wisconsin River bridge having been finished over the winter, tracks were laid to Wauzeekaw (Wauzeka), Wright's Ferry, and Bridgeport. With nine miles left to the Mississippi, the men picked up the pace. In the second week of April the last spike was driven at Lowertown, Prairie du Chien. After six and a half years the railroad from Lake Michigan to the Mississippi was finally finished. On the morning of April 15 the Milwaukee & Mississippi locomotive Prairie du Chien, pulling one baggage car and three passenger cars, left Milwaukee. It arrived at the depot in Lowertown at 5 o'clock in the afternoon and was greeted by cheers and a two-hundred-gun artillery salute. A barrel of Lake Michigan water that had been brought from Milwaukee was ceremoniously emptied into the Mississippi River. The North Iowa Times reported:

Be it remembered that on Wednesday, April 15, 1857, at 5 o'clock in the evening, the cars of the Milwaukee and Mississippi Rail Road anchored on the banks of the great river. The shriek of the Lake Michigan locomotive was echoed by the bluffs and responded to by a shrill whistle of welcome from a Mississippi steamer just coming into port. Hundreds of persons were in attendance to witness the arrival of the first passenger train, and when the smoke of the engine became visible in the distance there was such an expression of anxiety as we have seen when a new and great actor is expected on the stage. As the train came in view, and the flags with which it was decorated were seen waving in the breeze, a shout of welcome broke forth from the gazers that told how many hopes of friendly reunions were awakened in the contemplation of an easy and speedy return to their eastern homes. One large banner carried on its silken folds the busy emblem of “Wisconsin, the Badger.”12

Sadly, the high note of this momentous achievement was soon overshadowed. In May, shortly after the line was opened, there was trouble when water from melting snow and ice made the Wisconsin River overflow its banks. Superintendent William Jervis reported that the main line west of Boscobel was interrupted 2 weeks in May by the unusual freshet in Wisconsin River…. No danger or interruption would have occurred from this cause, had the embankments been finished to the contemplated grade, but in many places they were 1½ to 3 feet below, and the action of the water upon the frozen lumps which had been put in during the winter, settled them one, and in some places two feet lower, making 3 to 4 feet below the elevation of the established grade. These embankments have since been raised, and in most cases protected by stone, so that no apprehension need be felt of any similar difficulty in the future.

The effect of the interruption on the business of the road was … serious…. It resulted in our losing the bulk of the through spring business.13

The spring freshet had also raised the water to a level that prevented lumber rafts from passing under the railroad's bridges. Raftsmen, waiting for the water to subside, threatened to dismantle the bridges. The legislature subsequently passed a law that required the company to raise its Spring Green and Lone Rock bridges by three feet.

There was still more trouble to come. In their efforts to make ends meet, summer found the Milwaukee & Mississippi charging exorbitant rates in areas where there were no competing lines. The charge for carrying wheat from Madison to Milwaukee was greater than that from Prairie du Chien to Milwaukee, Prairie du Chien having shipping on the Mississippi as an alternative. Madison's Wisconsin State Journal pointed out that it cost as much for Dane County growers to ship their grain to Milwaukee on the Milwaukee & Mississippi railroad as it did to ship it by wagon-meaning the only advantage of using the railroad was speed.14 The company was increasingly pressured to resort to such measures as the economy deteriorated in May and June. In August, when runs took place on Eastern banks and Wisconsin banks suspended specie payments, the Milwaukee & Mississippi owed $4,798,705 and was committed to annual interest payments of $468,823. As its revenues dropped, the company found it more and more difficult to make those payments.15

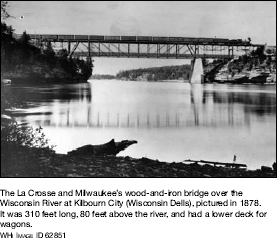

The La Crosse and Milwaukee Railroad Company began the year favorably, but trouble was on the horizon for them as well. On January 20 the company had contracted with Selah Chamberlain to finish its road from Portage City to La Crosse by December 31, 1858. The company opened its line to Portage City on March 16. That month the directors appointed W. R. Sill of La Crosse as engineer of the Western Division. Sill had surveyed the route between Tomah and La Crosse. Grading was commenced between Madison and Portage City-the first segment of the northwestern land grant route. Later, on August 20, the road to the village of Kilbourn (that is, the Wisconsin Dells) was also opened.

Despite this progress, the strain of continuing to finance their railroads on empty promises began to point to serious trouble ahead, even in the early part of the year. In January the La Crosse and Milwaukee Railroad Company purchased the St. Croix and Superior Railroad Company with one million dollars' worth of unsecured company bonds, thus securing the northern portion of the northwestern land grant route. These bonds, which had been issued to acquire the Milwaukee and Watertown, as well as those given out as “pecuniary compliments,” committed the company to eventually redeeming some two million dollars-no incidental amount.

As word spread regarding the company's distribution of “gift” bonds, a legislative investigation was called for. On President Kilbourn's recommendation, Moses Strong ran for state assembly to block the investigation. After Strong was elected, but before he could take his seat, the Chicago, St. Paul and Fond du Lac Company, hoping to wrest away the northwestern grant, asked for an inquiry. Milwaukee Democrat Josiah Noonan wrote Assembly Clerk Horace A. Tenney that he had many Republican legislators ready to vote for an investigation. But Kilbourn and Strong were able to pay Tenney to drop the investigation. The assembly's railroad committee subsequently stated that the investigation would have been expensive and would have harmed the state.16

During the summer there was more and more talk of the La Crosse and Milwaukee's “gift” bonds of the year before. President Kilbourn made the statement that he and Strong should not be considered “great scamps” simply because the honorable gentlemen of the legislature had chosen “to make asses of themselves.”17 Meanwhile, the company was once more in dire need of cash. On August 17 it mortgaged its completed sections, from Milwaukee to Portage and from Water-town to Midland, to Greene C. Bronson and James T. Soutter, trustees, to secure one million dollars' worth of 8 percent bonds.

On September 26 the company leased its entire line to its contractor, Chamberlain. Chamberlain was to operate the road and apply the net receipts to 1) the Palmer mortgage, 2) the Milwaukee city mortgages, 3) the second mortgage, and 4) the Bronson and Soutter mortgages. He could apply what was left to reduce the $629,089.72 that the company owed him.18 The company then leased its Water-town division to D. C. Freeman; as with Chamberlain's lease, Freeman was to apply net receipts to three mortgages, then to D. C. Jackson (who was owed for grading between Madison and Portage), and then to himself. The company did complete nineteen miles of railroad between Water-town and Columbus during 1857.

On October 29 the man who had been behind the development of Wisconsin's railroads from the beginning, Kilbourn, resigned from the presidency and ended his long association with railroads. Kilbourn also confessed that the La Crosse road was on the verge of bankruptcy and that the land grant, “so eagerly sought,” had, “by the expenses of the contest for its possession,” contributed largely to the “present embarrassments of the Company.” Stephen Clark of Albany, New York, was elected in Kilbourn's place.19

In December the La Crosse and Milwaukee's first train to cross the bridge at Kilbourn City gave its passengers a spectacular new view of the Dells. The bridge was 310 feet long, its track 80 feet above the river, and it incorporated a deck-roadway for wagons beneath the track. Chamberlain finished the line to Mauston on December 7 and to New Lisbon on December 23, making 138 miles of continuous track from Milwaukee. On December 24 the company sold its Watertown-Columbus line and the former Milwaukee and Watertown line (Brookfield Junction to Watertown) to the Madison, Fond du Lac and Michigan Railroad Company, a company which until then had owned no property.20 The La Crosse and Milwaukee then used the proceeds to pay D. C.Jackson for grading between Madison and Portage.21

At the end of the month the directors requested that Governor Coles Bashford certify the forty miles that had been built on the land grant route. The governor took the opportunity to first cash in his fifteen thousand dollars' worth of “gift” bonds. Then, on December 28, he certified the forty miles between Portage City and New Lisbon and forwarded the certificate to the Secretary of the Interior in Washington. The receipt of the granted lands was the company's last hope for survival, but with everyone involved trying to bank their bonds and get out, things did not look hopeful.

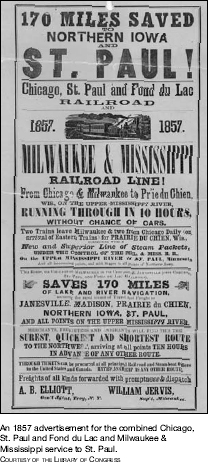

The Chicago, St. Paul and Fond du Lac's fortunes also shifted over the course of the year. In January it had absorbed by merger the Wisconsin and Superior Railroad Company, thus acquiring the northeastern land grant route. In March it merged with two Michigan railroads, the Ontonagon and State Line and the Marquette and State Line, to gain access to Michigan's Upper Peninsula and Lake Superior. The directors summarized that

the object and desire of the Chicago, St. Paul and Fond du Lac Railroad Company was the extension of their line from Janesville northwest via Madison and La Crosse to St. Paul and from Janesville north along the valley of Rock River to Fond du Lac and to the great iron and copper regions of Lake Superior.22

In other words, they hoped to be the first railroad to service the mining regions of the Upper Peninsula, which promised lucrative benefits.

Meanwhile, improvements were being made to the everyday workings of its existing lines. On March 19 the company implemented a new timetable between Chicago and Janesville. Trains left Chicago at 7 a.m., 8 a.m., and 2:05 p.m. for the four and a half hour journey. The 7 a.m. train stopped at Junction, Plank Road, Canfield, Des Plaines (7:50 a.m.), Dunton, Palatine, Barrington, Carey (8:55 a.m.), Crystal Lake (9:08 a.m.), Ridgefield, Woodstock (9:32 a.m.), Harvard (10:05 a.m.), Lawrence, Sharon (10:30 a.m.), Clinton (10:52 a.m.), Shopiere, and Janesville (11:30 a.m.). Return trains left Janesville at 7 a.m., 9:30 a.m., and 5:30 p.m. These improved operations were further explained:

Trains should meet and pass at stations marked with full faced figures. Freight Trains will take the side track to allow passenger trains to pass. Passenger Trains Nos. 2 and 4 will take the side track at passing place. No Train will approach a station when another train is to leave within five minutes of its time of leaving. Freight Trains will pass each other at Crystal Lake.23

In April, the Chicago, St. Paul and Fond du Lac line became part of the through route between Chicago and St. Paul. The company's agreement with the Milwaukee & Mississippi allowed it to share the latter's line between Janesville and Prairie du Chien. At Prairie du Chien passengers continued their trip on the steam-boats of the Prairie du Chien and St. Paul Packet Line to St. Paul. Author D. C. Prescott relates:

The Fond du Lac Road connected at Janesville with a railroad called the Milwaukee & Mississippi, which extended out to Prairie du Chien on the Mississippi River and a line of passenger boats operated between that place and St. Paul, Minn., constituting a continuous line by rail and river from Chicago to St. Paul…. The arrangement worked nicely so long as the water in the river was high enough to permit unobstructed navigation, but in times of low water, trouble was always in store for the connecting railroad lines, because the boats were constantly getting stuck on sand bars, which invariably made them late at La Crosse and Prairie du Chien; and then the race would begin to make up time and land passengers in Chicago in time for eastern trains…. Arthur Hobart had the faculty of landing lady passengers at way stations actually without bringing the train to a full stop. He simply gave them a toss in such a way that they would land easily on their feet and no harm done; and of course John Hull, the baggage-man, would drop off the trunks, and all this time Hobart's hand would be in the air signaling the engineer to go ahead. This was the kind of railroad service had every time a train was late.24

Meanwhile, there was the business of the Chicago, St. Paul and Fond du Lac closing the gap between Janesville and Minnesota Junction. President William B. Ogden visited Wisconsin to promote stock sales in the area. L. B. Caswell of Fort Atkinson recalled:

Mr. Ogden came here … in 1857, and … worked up large subscriptions for the stock, in the shape of mortgages and lands freely given the company for stock, and also by obtaining the towns and cities along the line to issue their bonds in large quantities, in payment for stock, and finally the town of Koshkonong, Fort Atkinson then constituting a part, issued to this company stock, $50,000, of its seven per cent, twenty year bonds, interest payable annually. Jefferson issued a large amount of similar bonds, and Watertown a much larger amount.25

The directors had resolved to put this part of the road under contract as soon as six hundred thousand dollars worth of stock was subscribed. This happened within a month when Fort Atkinson subscribed $100,000; Watertown, $150,000; Jefferson, $75,000; Johnson Creek, $25,000; and Juneau, $50,000. By May, however, economic conditions in the state had noticeably changed and investors had become more cautious. Henry E. Southwell of Fort Atkinson explained:

The spring of 1857 witnessed a decided change in the outlook for business. Credits began to be looked after. Distrust was in the air. Merchants forced their goods to sale and down went the price. It was an effort to get out, with or without loss … Collecting agents canvassed the courts trying to force payments.26

The downturn, starting in May, would have a devastating effect on the railroads. Later in the year the Chicago, St. Paul and Fond du Lac found itself, along with other railroad companies, unable to pay the interest on its bonds. But it continued to run trains and do business in this state of near-bankruptcy. It owned eighteen locomotives, fourteen passenger cars, and 120 freight cars at that time. Construction work, however, stopped, and the fifty-seven-mile gap between Janes-ville and Minnesota Junction remained. L. B. Caswell of Fort Atkinson described the state of affairs:

Mr. Ogden staked his entire fortune on building the road. He built on the north end from Fond du Lac to Minnesota Junction and on the south end, from Chicago to Janesville, and the company had exhausted its money and all its resources. It failed without a dollar in the treasury and no road to Fort Atkinson, none between Janesville and Minnesota Junction. Our $50,000 of town bonds were outstanding; we had the old worthless certificates of stock in the defunct road. We had helped to build some other places a road with our bonds, mortgages and lands, but had no road for ourselves. Property along the unbuilt portion was dead. Fort Atkinson was dead, for aught we could see.27

Undaunted, President William B. Ogden returned to Wisconsin to push for the completion of the line:

Soon after the panic of 1857 Mr. W. B. Ogden, president of the Chicago, St. Paul and Fond du Lac Railroad, pushed the construction of the road between Janesville and Watertown. Mr. Ogden told the people of Wisconsin that a direct connection with Chicago was better for them than with Milwaukee although the distance was 60 miles farther. That Chicago was and would be the best market for farm products and was the leading city in the West. Mr. Ogden was a man of large and wide experience. A talk with him meant new ideas and enlarged views. He liked to associate with men who did things and did them well.28

After Ogden's visit, the company optimistically planned to resume construction in the spring.

The Milwaukee & Mississippi, which had long been Wisconsin's premier railway, was fighting to stay afloat. By September its southern branch between Janesville and Monroe had been graded and was ready for track laying. Rails were laid eight miles to Hanover (a.k.a. Bass Creek or Plymouth), where they crossed the Beloit and Madison line. From Hanover rails were laid six miles to Orfordville, then six more miles to Brodhead. Brodhead had been founded two years earlier by Superintendent Edward H. Brodhead, now president of the company. At that time the nearby villages of Clarence and Decatur were told that they would have to raise seven thousand dollars to have the railroad come their way. Confident that the railroad would come their way in any case, they did nothing. In the spring of 1856 Brodhead responded by purchasing land midway between the two villages, platting the village of Brodhead, and donating land for station grounds and right of way. Buildings then went up “as fast as workmen could be found to put them up.” Soon residents of Decatur began moving their buildings to the new site. By September of 1857 Brodhead had two stores, a hotel, a lumberyard, and six hundred residents. On September 17 the editor of the Monroe Sentinel joined in the celebration of the opening of the line to Brodhead:

Early on the morning of a drizzling, rainy, muddy Thursday… we left… to attend the celebration of the opening of the Southern Wisconsin [Southern Branch of the Milwaukee & Mississippi] Railroad to Brodhead.… An excursion train of six passenger and three or four freight cars, all crowded full, left the [Brodhead] depot to meet the excursionists from Milwaukee, Waukesha, and towns along the line of road. At Janesville, the Milwaukee train of five crowded cars was added, and the train returned to Brodhead, arriving just in time to permit the whole company to take refuge in the large depot before the approach of a passing shower…. The Monroe Brass Band furnished an excellent quality of music for the day…. The Brodhead Brass Band also played excellently…. There was also a martial band from Decatur that participated in all the festivities.29

Leaving Brodhead, the track layers came to the twin villages of Juda-Springfield, separated by Main Street. The Monroe Sentinel reported:

November 18: The track-layers today [Wednesday] will have the rail laid into Juda, and by Saturday night, will probably have finished all side-tracks. It is now but eight miles from Juda to Monroe, and a little more hard work will bring the cars to this point. Let every man who has a cent in money or a bushel of wheat, pay the same to B. Dunwiddie, director, or Henry Thompson, Esq., agent, and those gentlemen will faithfully apply the same to the taking of iron out of bond. It will not do to let the track-layers cease until the last switch in this town is laid.

The Milwaukee & Mississippi had defaulted on its bond interest payments in July and had also been unable to pay storage and duty charges of twenty thousand dollars on rail imported from England and now impounded in New York City. The Bank of Monroe then paid the duties so that track laying could continue.30 The Monroe Sentinel continued to report on the story in installments:

November 25: Stock-holders and citizens along the line of this road are very much indebted to the Bank of Monroe, for the aid it has rendered and is now rendering, to secure the completion of our road. It has furnished money to carry on the work when no other bank in the State would loan a penny-a fact that must not be forgotten when the cars shall rumble into town.

December 6: By politeness of friend Graham, we paid another visit to the railroad, Tuesday. At the time we left, 4 o'clock p. m., the rail was laid half way across the trussel-work-which is half nearly a quarter of a mile in length. Today the train will run over it, and we have engaged a passage on the first car. The road is open within three-and-a-half miles of Monroe, and the work is progressing rapidly.

December 23: We are in high feather, we are elated. We feel good. Why? Go with us a few rods towards the southern portion of the village, and we will show you two parallel iron rails leading to the east and connection with all her roads, over which the strong engine with its ribs and muscle of iron and steel, is hereafter to play back and forth like the weaver's shuttle, fetching and carrying its load of men and merchandise … The cars have come to town, and every day “Richland timber” [the trestle over Richland Creek] echoes the scream of locomotive. The facts that our people have paid the M.&M.R.R. Co., thousands of dollars within a few weeks, and that the Messrs Graham have laid the rail at the rate of about half a mile per day, throughout the worst month of the year, all go to demonstrate one thing, namely, that this village is to be a little world of bustle and activity, from this time henceforth; and here we make the assertion, which we will prove by-and-by, by the figures, that Monroe will be the heaviest produce station in Wisconsin.31

And so the railroad came to Monroe. And with its arrival, construction on the Milwaukee & Mississippi line ended.

In the Milwaukee & Mississippi's annual report for 1857, President Brodhead declared the road finished with 192 miles of mainline, 42 miles of branchline, and 28 miles of side track. The road with fencing, depots, telegraph, real estate, and rolling stock had cost $8,235,512, of which $3,674,673 had come from stockholder contributions and $4,560,839 was borrowed. Construction proper had cost $7,703,330, or $32,863 per mile-exceeding estimates, yet comparable to other railroads. In the report, the directors revealed what everyone already knew-that the railroad was in trouble:

The past year, as is well known to you, has been one of great financial embarrassment. The railroad interest of the country, generally, has suffered severely from its effects. To these financial difficulties may be attributed, in a great measure, the increased cost of your road over previous estimates. The ruinous rates of interest, commissions, and exchange, the company have been obliged to pay, in order to carry a very large floating debt; the losses upon securities, sold to meet pressing engagements, and the sacrifice of others (pledged for temporary loans) upon forced sales, constitute large items in that increase.32

The directors also confessed that there was “a large amount due to employees, that has accumulated during the past four or five months,” and that “during the last three months a reduction of about 20 per cent has been made in salaries of agents and clerks, and in wages of laborers …”33 This despite the fact that the Milwaukee & Mississippi's net earnings in 1857, $470,617, exceeded those of the previous year.

Late in the year the Mineral Point Railroad began running its trains on a regular schedule. It left Mineral Point at 6:45 a.m. and reached Warren at 8:45 a.m. It returned leaving Warren at 9:45 a. m. and arriving back in Mineral Point at 11:45 a.m. The company did well despite the depression due to the guaranteed $56,000 it received annually from the Illinois Central and Galena and Chicago Union companies.

Most companies, however, did not fare so well. During 1856 and 1857 the Manitowoc and Mississippi Railroad Company had graded its roadway between Manitowoc and Menasha but now, like many companies responding to the financial crisis, it suspended all work.

Late in 1857 Racine and Mississippi President H. S. Durand stated what many felt to be true of the railway's immediate future:

The fact is the state of the times for railroad operations is frightful and the prospect is dubious in the extreme. It makes no difference how low you offer securities, nobody wants them. People have been swindled so much and disappointed so often in railroad investment that they have come to regard them all as valueless.34

President Durand's statement captured the extent to which the high hopes held by most at the beginning of 1857 had fallen. Looking back, the euphoria of a Wisconsin railroad reaching the Mississippi in April had died with the economic recession that began in May. It was true that with the transstate line operating, shipping by rail quickly came to predominate shipping by steamboat as measured at Prairie du Chien and at McGregor, Iowa, on the Mississippi-but the total volume of shipping dropped dramatically. Milwaukee & Mississippi superintendent William Jervis reported at the end of 1857:

The freighting business on the Upper Mississippi river during the past season was much larger than the previous or any former year. But the increase was all in the earlier part of the season, at the time when we were not ready for it… so that in reality we had only the benefit of through business about six months of the current year, when business of all kinds suffered from … the commercial crisis.35

That said, revenues were being earned on the line between Milwaukee and the Mississippi as general merchandise, coal, iron, brick, and lumber were carried westward and wheat, corn, hay, barley, oats, hides, and pork were carried eastward.

Despite the economic recession and the bank panic that had occurred in August, 192 miles of track had been laid in Wisconsin during 1857-more than in any previous year-bringing the state's total to slightly over 700 miles. Lines were extended from Boscobel to Prairie du Chien, from Midland to New Lisbon, from Watertown to Columbus and Waterloo, from Ripon to Berlin, from Janesville to Monroe, and from Darlington to Mineral Point. Through-service had been established from both Milwaukee and Chicago to the Mississippi at Prairie du Chien. But the construction of these extensions had been achieved with borrowed money, and with the decline in business, the ability of the railroads to repay that money was diminishing. The Milwaukee & Mississippi was a case in point. Knowing it could not rely on revenues to make timely payments on its debts, in September it executed a second mortgage on its entire line from Milwaukee to Prairie du Chien.36 At the end of the year, the company reported holding capital stock of $3,674,672 and outstanding bonds (loans to the company) of $3,735,500- a balance that could not have made stockholders comfortable.

And so it was that Wisconsin's railroads arrived at the Mississippi and promptly fell into hard times.