The Painting in the Parlor

That August had been cooler than typical, for which I was grateful, and my evening walks were more pleasant because of it. On that particular night, with the apparent sunset occurring unnaturally early due to the heavy clouds overhead, I was met at my door upon my return by my faithful housekeeper, who handed me a telegram.

As she shut the door on Queen Anne Street, I opened it to discover a terse communiqué from my old friend, Sherlock Holmes: Available tomorrow for epilogue to old case.

It was no surprise to receive such a laconic message. In fact, I had the manuscript of one of our old investigations, relating to the strange events of nearly twenty years before in the home of Professor Presbury, lying on my desk upstairs, to be submitted at some unspecified point in time to The Strand. It had begun with just such a message from the famous detective, summoning me to his side with the certain assumption that I would join him. My only question about the current communication was whether my friend meant to end the seven words with a question mark, or if it was a declarative assertion. I suspected that it was sent exactly the way he intended.

No time of arrival was given, but if he was traveling up on the usual train from where he’d lived since his retirement, in a “villa” near Beachy Head, I knew when he would likely appear.

I was correct, and my bell rang promptly the next morning at the expected time. I made my way to the door to greet my friend, who had already been admitted by the housekeeper.

“No bag?” I asked.

He shook his head. “I’m only up for the day. A coda related to an old case.” He followed me into my study. “In any event, I have had enough traveling for a few weeks.”

“And how was Dublin?”

“Wet and cold, the same as here. What an unusual August.”

I knew that he had been in Ireland earlier in the month for the formal transfer of Dublin Castle to the Irish Republican Army. The Empire would probably never know what he had accomplished when unexpectedly involved at the last minute in that tense and frustrating imbroglio.

Holmes explained that we had time for a cup of tea, and we chatted about the old days. He informed me that his brother Mycroft, who had remained at his post even after the War, finally intended to retire the next month. We both agreed that it would truly be the end of an era, except for the fact that he would not truly retire, no doubt continuing to provide his unique skills as a fixture at the Diogenes Club until they carried him out.

Finally, Holmes stood and said it was time to go. “Are you game for a walk?” he asked. When learning that we only had to make our way to Montague Street, I let him know that I was more than able.

We wound down into Wigmore and Mortimer Streets, and on across Tottenham Court Road. The morning was still cloudy but not unpleasant. We trod near that house close to the corner of Gower and Keppel, which I shall always associate with the murder of old Mr. Raines. Finally, passing behind the Museum, we entered Montague Street.

As usual, the short street was very quiet, considering how close it was to Russell Square on one end and Great Russell Street at the other. Our footsteps echoed off the stone faces of the houses. On the right, the edifice of the British Museum loomed over everything. Holmes and I had strolled in companionable silence for most of the way, and I wasn’t surprised when we stopped at No. 24, where he had lived when first coming up to London, now nearly fifty years before.

There was a handsome brougham parked in front, and as we had approached, a portly man in his late sixties, a contemporary to Holmes and myself, hefted himself with a grunt onto the pavement. I recognized him at once.

“Watson,” he said. “Good to see you. And Holmes,” he continued. “How long has it been?”

“Two years, Sir Clive. The matter of the fraudulent McGander.”

“That’s right. That was a snorter.” He waved his stick toward No. 24, now joined with No. 23 next door, and part of a hotel. “Shall we go inside?”

Still ignorant as to the reason for our visit, I followed them up the short flight of steps. We rang the bell, and in a moment a girl answered with a curtsy. Sir Clive stepped in and we followed him into the hallway. Apparently we were expected, as no explanations were given or required.

At the very back of the hall on the left was the door to the parlor. Beyond it was a narrow passage to the kitchens beneath us, and then the very narrow and steep stairs leading up to the lodger’s rooms. I recalled that Holmes had occupied a room on the top floor front when he first came up to London, although he had finally been able to afford something a bit larger, lower down on the first floor, in the year before he had moved to Baker Street.

“They think they’ve identified the painter,” Sir Clive said to me, turning to make this whispered comment.

Making our way to that curiously curved parlor door on our left, Holmes said, “Officially, then? We established that fact to our own satisfaction almost half-a-century ago.” Sir Clive harrumphed.

Stepping through the door, I still had no idea what this was about, but I certainly remembered the painting to which he referred.

“Yes,” answered Sir Clive, “but Richardson, from around the corner in Russell Square, has been doing some research lately, and he wants to write something up for the journals. And then there’s talk again of removing it and selling it to a collector. They asked me to be here today, and I thought of inviting the two of you. ”

“Remove it?” scoffed Holmes. “Impossible.”

Entering the oddly-shaped room, squared at the front windows but rounded at the back, we encountered a grouping of three other men, standing opposite to us beneath a tall and wide painting, about six feet square, affixed above the fireplace. Strangely it didn’t hang there, as it was painted directly onto the plaster. I had seen it before on the few occasions when I had visited this address, most notably to investigate a murder on the top floor in Holmes’s old room that had taken place a number of years earlier.

“Richardson,” bellowed Sir Clive to a scholarly looking fellow, thus identifying for me the man in question. “Still trying to nail down the provenance of this old painting?”

The man responded good-naturedly. “You know how it is to get a bee in one’s bonnet, Clive,” he said. “I have some fresh correspondence from the Duke of Bedford that almost makes it certain that the painter was James Ward.”

“I’ve told you that it was Ward for the last forty years. I knew it when I first saw it, and we had additional confirmation from Abel Granger’s people, who had hired Ward to paint a very similar painting. The man,” said Sir Clive to me, “was rather specialized in what he liked to paint.”

“Anecdotal evidence is certainly valuable,” sniffed Richardson, “but one’s case is always so much more solid with the written word.” He reached into his breast pocket and pulled out a packet of folded yellow papers. “Letters, Sir Clive!” He waved them about. “The proof!”

“I don’t need any such proof,” said one of the other two men. He was a cadaverous looking fellow with unhealthy dark hollows under his cheeks. Speaking with an American accent, he added, “I recognized it for a Ward from the minute I saw it. Those letters will simply make it even sweeter when it’s hanging in my own little museum in Pittsburg.”

“And I can’t make it any plainer than I already have, Mr. K--------,” said the third man, whose origins were clearly British, “that the painting cannot be moved. It was applied directly onto the ordinary plaster surface above the mantel. A massive and expensive effort would have to be undertaken to remove it, and even then it’s likely that you would fail. We would need to construct a special steel underpinning and frame, and after all of that, it would likely crumble to pieces.”

Sir Clive gestured with his thumb toward the third man. “Grigsby. British Museum.”

The man nodded, looking curiously at Holmes and me, obviously wondering why we were there. Sir Clive made no move to introduce us.

The American shrugged his too-heavy coat up around his thin shoulders. “Don’t care. Whatever it takes. Money is no object. And keep looking for that canvas version as well.”

“It was lost nearly a decade ago,” said Grigsby.

“Money’s no object,” K-------- repeated, and then, with a quick and hungry look toward the painting, he turned and stalked from the room. Grigsby looked with frustration to Sir Clive, and then hurried to follow.

We three and Richardson were left in front of the fireplace, naturally turning our gazes upward at the object under discussion, I had seen it before, of course, but had never given it more than a passing glance. Now, I studied it more carefully.

It was a landscape, done in rather unpleasant yellows and browns. The upper two-thirds portrayed a brassy sky, with sour-looking and strangely lit clouds mostly hiding the light but dull blue that peeked through in just a few places. On the ground beneath them was a rural and timeless scene, tedious in its plainness and, frankly, lack of imagination. In the center, taller than almost anything else in the painting, was a figure seated on a downtrodden white horse, both man and beast with their backs to the viewer. The rider, in a brown hat and matching brown clothing, was holding out a hand to a boy at his right. The lad was wearing a blue coat and red pants – the only unusual colors in the whole artwork. The man on the horse seemed to be reaching for a hat that the boy was offering, in spite of already having his own hat upon his head.

Incongruously, there were three cows spread around them, all of apparently different breeds (or so it seemed to me, as I know little of cattle), two lying down and one standing, facing indifferently away from the men and beasts. To the left, the land dropped off to a dark hollow and distant forest, while on the right, set back at what seemed to be a couple of hundred feet, were some ill-defined trees, with the lop-sided roof of a two- or three-story house barely showing amongst them. It was competently painted, no doubt, but not – to my view – anything that would inspire a collector to declare, “Money’s no object.”

“It was the cows,” said Sir Clive, to my obvious confusion and his amusement. “That’s how I first knew it was a Ward, you see. The old Duke of Bedford, who owned of all the property around us, including this house – and the family still owns it, by the way! – took Ward under his wing over a hundred years ago. Ward, you see, was the most popular painter of cattle of his day.”

“Cattle?” I said. “Are you serious? That was a specialty?”

“A most sought-after specialty,” asserted Sir Clive. “The early 1800’s was a period of romanticism, a reaction against classicism, wherein people wanted paintings that glorified nature and invoked an emotion, sometimes with a solemn and mysterious feel.” He gestured at the painting and glanced toward Holmes, who had remained strangely tacit the entire time. “Of course, we know what the mystery connected to the painting was. Eh?” Richardson, who had been pondering the illustration, silently glanced toward Sir Clive, who continued, “In any case, the Duke of Bedford hired Ward to paint this picture for this particular house, although we never did find out what the significance of this house was. According to the records, this house wasn’t built until 1808, and by then Ward had become somewhat separated from the Duke’s sphere of influence, having long since departed from the Bedfordshire home of his lordship, where he stayed for quite some time.”

“Old news,” Richardson snorted, his patience fractured. “I must be about other business. Good morning, gentlemen!” And he turned and left without a backward glance.

Sir Clive gave a short bark of a laugh – “No great loss!” – and shook his head.

“You obviously have researched this subject,” I said. “And this painting is connected to the old case that you mentioned, Holmes?”

But my friend was staring fixedly at the bottom right corner of the painting, where the brown hill rippled as it dropped towards us, away from the subjects, cattle and otherwise. There was a slight crack there, and that corner appeared to be on a somewhat different plane of plaster.

Sir Clive followed his glance at the corner of the painting as well. “It will be gone in another ten years, I’m afraid.”

“Yes,” said Holmes. I leaned in to see the object of their comments.

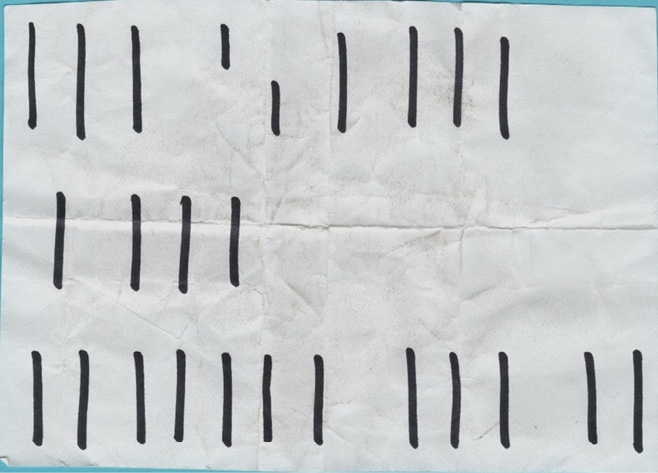

Low in the corner, near the simple wooden frame that had been constructed around the painting, were a faint series of vertical marks, three rows of them. Each row was quite small, no more than a quarter-inch in height, and there appeared to be no pattern whatsoever. They looked to be composed of some sort of flaked metal, golden colored, that had been pressed on top of the paint.

“Is that – ?” I asked.

“Yes,” replied Holmes. “Gold leaf. Although there is less of it there now than there was back in 1875.”

“Is there gold under the painting? Is that why Mr. K-------- desires it?”

“No, no. Those markings were put there in 1811, not long after the painting was made, by a man who was staying here in this house at the time.”

“But why was gold leaf applied onto a painting such as this, with its otherwise unpleasant brownish tones?”

Sir Clive laughed with surprise. “You haven’t told him, then?”

Holmes shook his head, replying, “I thought that it would make for an interesting narrative later today. Can you join us ‘round the corner?”

Sir Clive shook his head. “Much as I would like to, I must get over to Ratham’s. The old scoundrel is auctioning a widow’s estate, and I promised that I would stop by.” He glanced at me. “Just when you thought you’d heard them all, Watson, it’s time for another one!”

With a last glance at the artwork, he turned to go, leading us back out to the street.

“Until we meet again, gentlemen,” he huffed as he fit himself back into the brougham. Then, with a lurch, it set off toward Great Russell Street, and so to the right and out of our sight.

Holmes gestured in the same direction, and I agreed. We set off at a leisurely pace. Mere moments later, after passing in front of the gates of the Museum, we were seated in the back of the Alpha Inn. It was a bit early in the morning for it, but we bravely faced the pints of the landlord’s excellent beer in front of us.

After taking a swallow, I cleared my throat and said, “I believe there was mention of an interesting narrative? Set back about 1875?”

Holmes nodded and fished in his coat. Pulling out a packet of folded and worn slips of paper, he flattened them and then tossed two upon the table, retaining the third. “What do you make of these?”

They were each three or four inches across, and the paper was quite worn. I picked them up. “They are old,” I said.

Holmes gave a short laugh. “Be careful how you toss around someone else’s dates so easily, my friend,” he smiled. “These are all that I have left of an odd little mystery that took up a day or so when I was but twenty-one, and had only been up to London for less than a year.”

“You brought them with you today when Sir Clive asked you to drop around at Montague Street.”

“Obviously. I still look back with fondness at this little case, and when I heard that someone else was considering, yet again, the purchase of the Ward painting from the No. 24 parlor, it seemed to be the perfect opportunity for a bit of reminiscing.”

I tapped the scrap on the left. “This looks like the gold leaf markings on the corner of the painting.” I lifted the sheets and examined them. “I assume it’s some sort of code. What about this other sheet?” I recalled what the American had said. “Were these other markings on the missing canvas version of the painting?”

Holmes, in the act of swallowing, lowered his glass and smiled. “Very good, Watson. You are correct. Shall I tell the entire tale wrong-way around, or would you like to hear it from the beginning?”

I returned the squares of paper to the table and nodded to for him to tell it in his own way. He was correct. This wasn’t some potboiler, after all, to be revealed just for the drama of the thing.

Settling back, Holmes began. “It was in the fall of ‘75. I had been in London a little over a year, having settled into Montague Street and working to master my new craft. My landlady, the wife of one of my father’s cousins, had several other lodgers, and she’d grudgingly taken me in as well. There were only a few of us regulars there, as more often than not rooms were taken by nearby University students who soon found better or worse accommodations, depending on their prospects, before moving on.

“It was a late afternoon in early October when there was a knock at my door. I opened to find a man in his thirties, well dressed, and trying to catch his breath from the steep climb to my top-floor rooms. I had observed him on several occasions since his arrival earlier in the week. He was what I considered to be a short-timer, as there had been no indication that he had moved in with more than what would be needed for a few days in the capital. No matter what time I had arrived or departed during the recent days, he had been in the parlor, staring at the painting that you and I were admiring just a quarter-hour ago. I had been curious about the object of his fascination – you have seen that it isn’t the Mona Lisa, after all – but it had been none of my business.

“‘Mr. Holmes?’ he wheezed. Clearly, climbing six flights of stairs was not part of his normal routine.

“I observed that he was left-handed, smoked Trichinopoly cigars, had attended Corpus Christi College at Cambridge, hunted with a bow for sport, had written letters both the previous evening and again that morning, as shown by the overlapping ink spots on his fingers. He suffered from digestive complaints, was unmarried but with sweetheart, had a slightly built-up left shoe manufactured by Tundell’s off the Strand, and that he was from north of London. In his hand, he carried a rolled canvas.

“I nodded to indicate that he had found the right man and motioned for him to enter. He dropped into my sole visitor’s chair near the front window, standing the painting, for it was unrolled just enough to see that that was what it was, beside him.”

“‘Early 1800’s, I’d venture,’ gesturing toward it.

He glanced toward it in surprise. ‘Why yes? How did you know?’

“‘I’ve made a study of both canvas and paints. I can tell from the portion of the sky revealed there that it is from that general period. Does it relate to the painting that you have been pondering so steadfastly downstairs for the past week?”

He looked at me as if I were some sort of necromancer and nodded. Then he bent and unrolled it upon the floor between us. The setting sun hadn’t quite yet fallen behind the Museum, and there was still enough light to pick out the details. I slid from my chair to the floor, kneeling to lean closer. It was clearly by the same painter as the one downstairs in the parlor, and in many respects, it was the same scene, though perhaps the better of the two. This painting did not have the dingy yellow-browns of the other. Rather, it was brighter, with the clear blue skies giving it a more fresh feeling. However, the man on the horse, the boy, and the cows were practically identical. Yet the background was different – this was a bluer sky, as I said, and instead of a distant dark grove of trees on one side and an old house on the other, there was a manor house in the distance, more centered behind the horseman, as if he had been interrupted by the boy while on his way there. Instead of a hat in the boy’s hand, the rider was curiously handing him a knife. Ignoring the safe way to do such a thing, the man on the horse had retained a normal grip on the handle, leaving the boy to reach for the blade. In the foreground was a stream with various rocks piled along its banks, looking as if they had been cut and arranged there long ago by masons to prevent the bank from eroding.

“‘Interesting,’ I muttered, then looked up. ‘I suppose there is some reason that there are two of these paintings. Perhaps a message?’ He nodded, and when I added, ‘A treasure hunt?’ he clapped his hands together.

“‘That’s it exactly!’ he cried. ‘They told me that you were some sort of detective, and that you know things that others do not. I can see I’ve come to the right place!’

“I had, in truth, seen a few things already, but I needed to know more. Returning to my seat, I said, ‘What is the history of these paintings?’

“He nodded, as if that were a fair question, and began. ‘My name,’ he said, ‘is Edward Cavenham, and my people have lived near Bishop’s Stortford since beyond memory.’ He pointed toward the painting on the floor. ‘That’s the family house there in the background. It doesn’t look much different now than when that was painted – ‘

“‘The year being – ?’

“‘Early 1800’s. That fits with the story I’m going to relate, as we have learned from letters handed down within our family. In 1810, my grandfather, Richard Cavenham, was serving in the Royal Navy, against the wishes of his father, Lloyd. He was at the battle of Grand Port, when the French forced the British surrender following the failed attempt to blockade the Isle de France. He was taken prisoner, but because he was an officer, he was treated with dignity, even being entertained in some of the finer French homes.

“‘While there, he became immediately enamored with his host’s daughter, Lisette Duvelle. Within a few weeks, they had wed. It is not recorded what Lisette’s father thought, although there seems to have been no objection, but the upshot was that my father’s release was negotiated, and he returned with his new bride to the family home in Hertfordshire, hard upon the Essex border.

“‘The fine treatment that Richard received in France was not reflected in England. Lloyd was outraged that his son had married without his permission or influence, and worse – that he had married a French girl to boot. Before long, things became intolerable, and Richard and Lisette departed, indicating that they were returning to France, where their union had been received with acceptance.

“‘However, when he left, Richard took with him his father Lloyd’s most prized possession, a jeweled dagger that one of the Cavenham’s had received from Charles I after helping the king escape from the Siege of Oxford in 1646. Richard left a note for his father, informing him that he had taken the dagger to pass along to his own child, now being carried by Lisette, as nothing else could be counted upon from Lloyd.

“‘Lloyd was beside himself, not with rage, but rather with the sudden realization that his narrow-minded reaction had driven his own son, and now future grandchild, from his home. He sent agents to France to look for Richard and Lisette, assuming that they would immediately return to her family’s residence. What Lloyd did not know was that Richard and Lisette had actually first come up to London for a time while they figured out what they wanted to do. In fact, they stayed right here, at No. 24 Montague Street.

“‘It was while here that Richard encountered a painter who had been commissioned, by the Duke of Bedford, to create the painting that you see down in the parlor. He struck up an acquaintance with the fellow, and then he had a second painting made – ‘ and here he pointed toward the canvas unrolled at our feet – ‘this one.’

“‘An interesting story,’ I said, ‘but how do you know of all this?’

“Cavenham removed a few folded sheets from his pocket. ‘The story has come down through the family through my great-grandfather Lloyd, who wrote down what he learned after the fact. It seems that, after Richard had the canvas painting made, he sent it, along with a cryptic message, to his father Lloyd. Then, he and Lisette left Montague Street and continued their delayed journey to France, where they did return to live with her family – although after Lloyd’s agents had initially searched for them there, thus missing them.

“‘However, Lloyd had previously convinced Lisette’s parents of his good will, and that he was truly penitent for his earlier reactions. They secretly sent word to Lloyd of the arrival of Richard and Lisette. But this was the spring of 1811, and Anglo-French relations were even worse. The British had defeated the French at the Battle of Lissa just a few months earlier, and it was difficult for Lloyd to arrange passage to France so that he could apologize in person. When he finally arrived, he found a newborn grandson, and also that his son Richard had recently passed away due to a sudden fever.

“‘Amazingly, Lloyd was able to convince Lisette to leave her family and return with her baby to England with him, where he would be raised in the house of his ancestors. That child was my father, William Cavenham, and he grew to be a very fine man indeed. His own grandfather, Lloyd, accepted them completely, and he was raised with every advantage. And yet, throughout his life, the circumstances of his own father Richard’s departure, and the question of where the jeweled dagger was, hung like a shadow over our house. It still does, to the present day. For when Lloyd found Lisette, he learned that she did not have the dagger, and it wasn’t discovered in Richard’s effects. They came to believe that perhaps the painting sent to Lloyd, along with the cryptic letter, gave some sort of clue to the dagger’s location. It has haunted my father William throughout his life, even now as he approaches his final days.’

“‘May I see the documents from your great-grandfather, as well as the message from Richard?’ I asked. He handed them to me silently, and I flipped rapidly through them. They were quite old and faded, a mixture of Lloyd’s own summary of events, as well as communications between Lloyd Cavenham and Lisette’s parents, all confirming my client’s story. I set them aside and looked at Richard’s communication with his father.

“It was a quarto-sized sheet on cheap rag paper. Both it and the faded ink were consistent with that manufactured in the early nineteenth century. The message consisted of four stanzas. This is a copy I made at the time.” He pushed the third folded sheet toward me, joining the two already on the table. I read:

Top to bottom

Side to side

Bitter old man

Family divide

Treasure loved more

Than faithful son

Now lost both

‘Til puzzle is done

For future heirs

Right under your nose

Preserved for them

From time’s flows

Not to be found

‘Til divide is combined

The paintings are key

The treasure you’ll find

I raised an eyebrow. “Treasure hunt indeed.”

“Exactly.”

“It mentioned paintings, plural. Had they never questioned that fact before discovering that there was a second painting?”

“It had apparently escaped them.”

“And how did the paintings relate?”

“That is what I attempted to find out from my visitor. ‘This painting,’ I said, pointing toward the floor, “was sent with that message.’ He nodded. ‘How did you find out about the one downstairs? I assume that you only recently learned of it, which explains why you’ve come up to London to study it.’

“He looked surprised that I had determined this, but said, ‘That is true, Mr. Holmes. For years, the poem and this painting have been in our family, as we’ve all had a go at trying to figure out Richard’s intentions. Of course, old Lloyd died long before I was born, but I still remember how my grandmother Lisette would puzzle over it. Quite frankly, it’s haunted my father, William, his whole life. Obviously, Richard meant for his father Lloyd to be able to solve it, taunting him to recover the dagger. He must have hidden it somewhere, since he didn’t have it in France when he died, and Lisette knew nothing about it. The poem says that the painting is the key, but we could see nothing in it that would tell us anything. What could we discover from a man on a horse, or a boy, or three cows?

“‘But just a few weeks ago, we had a man that came down to work on some of the gas jets, and he happened to notice the canvas painting lying out on one of the desks in the library. I confess that I’ve often studied it and the riddle over the years, trying to get behind Richard’s thinking, and more so recently, since my father’s health has started to fail. I’d dearly love to find the dagger and restore it to his hands before he passes. He hasn’t been well, you see.’

“‘And this man saw the painting, and remembered where he had seen one very much like it.’

“‘Exactly. He mentioned it to the cook while taking some refreshment in the kitchen, she told the butler, and he told me. I questioned the workman, and he said that the other painting was here, just a stone’s throw from the British Museum. I quickly decided to come up to London and see it for myself. I’ve stayed longer than I initially intended, hoping each day to find a clue to the dagger’s location. But I have no idea where the setting in the painting downstairs is located, and there is no more to be learned from the man, the horse, the boy, or the cows in that painting than there is in this one.’

“I confess, Watson, that up to that time, I hadn’t paid much attention to the painting in the parlor. It isn’t very attractive, as you’ll agree, and in general, my time in that room was generally spent in deep thought when I could no longer stand to be in my top-floor chambers. I felt that further study was required, and also a second opinion was needed. I sent word – ”

“ – to Sir Clive,” I interrupted.

He nodded. “Just Clive Bartleby then. A relatively new acquaintance that I’d made at the Museum while carrying out my diverse studies. Even then, he was making a name for himself. I sent a message around to his office, asking him to step over if convenient.”

“And not if inconvenient, come all the same?” I asked with a smile, recalling my friend’s message from the day before.

“It was implied,” Holmes responded. “Cavenham and I were in the parlor, looking at the painting, when Clive bustled in. After introductions were made, under the baleful glare of my landlady, we explained in hushed tones – for there were several other boarders enjoying the cool October breeze coming in from the tall open windows – about the two paintings, the message, and the long-lost dagger. Clive unrolled the painting, held it wide between his outstretched arms, and compared it from different angles to the larger version above the mantel.

“He nodded and muttered for some time, and he was clearly onto something. I knew better than to interrupt, but Edward Cavenham was becoming increasingly impatient. Luckily, at the moment Edward was about the burst, Clive was ready to speak to us.

“‘Clearly, it’s by Ward,’ he said, lowering his arms. “Funny that it’s been so close, and no one has bothered to identify it before now.’

“‘What?’ asked my client. ‘Who?’

“Clive went on to relate what he explained earlier this morning, as to how James Ward had been commissioned by the Duke of Bedford to create a number of paintings in the early 1800’s. ‘Obviously, he was hired to create one here as well, although there’s no telling why in this particular house without further research. The Bedford Estate has owned this property since the mid-1600’s, long before the houses were built. No doubt, the Duke simply wanted to provide a painting for whomever lived here then, or to give Ward another job, or both.’

“‘Perhaps the Duke of Bedford was friends with Richard,’ said Edward Cavenham, almost hopefully. ‘Possibly that’s why Richard and Lisette came here to stay before going on to France. They may have intended to stay here permanently.’

“‘You forget your own evidence,’ I pointed out. ‘The letters indicate that this was simply a stopping point along the way. Lisette apparently gave no indication that they knew anyone at this location, or that there was anything special about it.’

“‘But the painting!’ he cried, pointing at the wall. ‘You can’t deny that connection between this painting in this house, and the painting sent to my great-grandfather Lloyd.’

“I turned to Clive with a little idea that had been in the back of my mind. ‘Is it possible that the dagger is concealed behind the painting?’

“He shook his head. ‘Oh, I shouldn’t think so. This one is painted directly onto the plaster. I can’t imagine that destroying a work of art would have been an acceptable price to pay in order to retrieve the dagger. After all, according to what you’ve told me is recorded in the letters, Richard Cavenham struck up an acquaintance of sorts with Ward while they were here, getting him to paint the second picture that was sent to his father after this one was finished. I don’t believe that Ward would have been party to anything that might lead to the future destruction of his work, should someone have to remove the plaster to get at the dagger.’

“Edward looked at the painting on the wall. ‘I know that my painting is of our family estate. Where is the setting shown in that painting? Could the house beyond the trees be the location of the dagger?’

“‘No,’ Clive answered with certainty. ‘The plaster painting is clearly the meadow lands near Camden Town, with the northern heights in the distance – at least how they looked sixty-five years ago.’ He shook his head. ‘I’ve seen something of the sort before.’

“‘But perhaps the house in the painting…’ Edward added hopefully.

“‘Not likely. If it was a real house, it looks as if it was headed for collapse, even then. And that area is greatly built up since those days. It certainly would have been pulled down long ago.’

“Edward looked as if the wind had gone out of his sails, but I had noticed something on the painting on the wall.”

“The little vertical lines in gold leaf in the right hand corner.”

“Ah, Watson, my bag of tricks is truly emptied. You see right through me. I can remain in Sussex, and you can take over here in London.”

“That role is already being capably handled by your protégé in Praed Street, not to mention our Belgian friend in Farraway Street and Thorndyke in King’s Bench Walk. No, I was able to see where this was going from years spent getting events down in my journal in a linear manner.”

Holmes smiled, drank the last of his beer, and continued. “As Clive and Edward had talked, I began to notice, in the last rays of sunlight streaming through the high windows, the glint of the lines to which you referred. Stepping closer, I saw, well, I saw this…” And he put a finger on this sketch:

“Calling Clive over, I asked him what he thought. He leaned closer, and then stepped back, scanning the entire painting. ‘No, it only appears in that corner. I wonder what it could mean…’

“A sudden thought occurred to me. ‘Top to bottom. Side to side. I wonder – ” Stepping over to one of the residents sitting in a deep chair underneath the window, an unhealthy looking student obviously from Aberdeen with three sisters and a secret shame that he wasn’t hiding very well, I asked to borrow a few sheets of paper. He nodded wordlessly and handed me these very sheets you see before you, upon which I sketched the lines and copied the little verse.

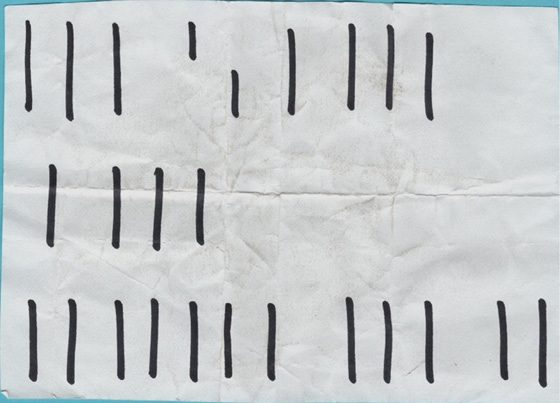

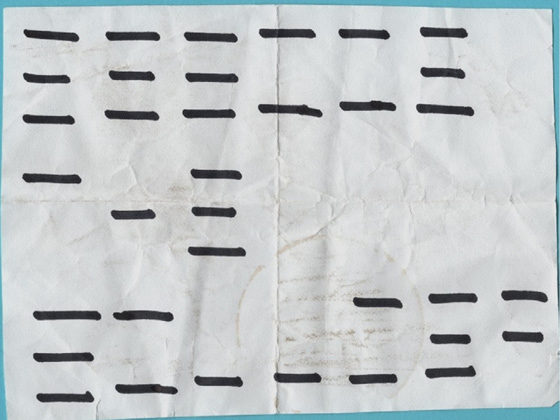

“Clive and Edward looked puzzled, but I reached and took the canvas painting, stepping to a side table. They quickly caught my intent, and joined me, each looking for matching gold-leaf lines on that picture as well. As it was much smaller, only about two feet square, it quickly became obvious that there was no golden glint whatsoever. But I did see another set of lines, the lines copied on this other sheet of paper here. Not in gold, but in blacks and browns. And not vertical, like in the mantel painting, but rather horizontal.”

“Side to side,” I said.

“Yes. On one of the rocks that were lining the stream.” He rearranged the sheets on the table, turning the second that I’d also placed in the vertical position on its side. “So now they looked like this from the parlor painting…”

“And this from the canvas painting…” he continued, placing the other beneath it.

“They almost line up,” I muttered.

I examined them again, realized after almost grasping it that none of it yet made sense, and admitted as much. “Ah, Watson, remember the poem. It was the only clue that Richard sent to his father. There had to be enough there to solve it. Perhaps there was some shared reference point between the two in their past that Richard thought his father would understand. The first stanza clearly refers to the lines in the paintings – top to bottom and side to side – and the feud that had sprung up between father and son. The second and third elaborate on Richard’s division from his family and the taking of the dagger. But the last stanza – that was the answer.”

I read it again, aloud. “Not to be found ‘til divide is combined. The paintings are key. The treasure you’ll find.” And suddenly it made sense. Top to bottom, side to side… combined. Holmes smiled when he saw me catch up, and leaned back with a satisfied sigh when I picked up the two sheets and carried them over to the window. It wasn’t as bright as I would have liked out in Museum Street, as the morning light had still not quite illuminated it. But it was enough. Laying one sheet atop the other, I pressed them up against the glass and read the message, formed when the vertical and horizontal lines combined.

“‘BESIDE THE BOULDER’.”

“Precisely.”

Turning, I asked, “And did you hold the sheets up to the parlor window when you figured it out?”

“The sun had already set behind the Museum at that point. I positioned them in front of one of the lamps.”

I returned to the table, folding the three pages. Offering them to Holmes, he waved them back to me. “For the archives, Doctor.”

I resumed my seat, wondering about another beer. It was later than before, and listening was thirsty work. Not to mention following in the footsteps of Sherlock Holmes.

My friend must have divined my thoughts, for he stepped to the bar, returning in a moment with two fresh pints. “Shall we adjourn in a bit for lunch at Simpsons?” he asked, checking his watch, and I agreed.

Wiping my mouth, I said, “I think I understand. Was it the boulder shown beside the stream in front of the manor house?”

He nodded. “Yes. In the canvas painting, where the horizontal lines are marked across the stone.”

“Without knowing about the second painting in Montague Street, in spite of the reference to paintings, plural, they never had a chance of solving it.”

“I expect that Richard intended to give his father further clues. Perhaps it was his unusual way of keeping the lines of communication open. Or possibly it was done in anger, to taunt him. But before he could elaborate, he died of the unexpected fever. Lloyd brought Lisette and the child, William, home, and they never knew that there was any more to the riddle. Only a chance visit by a gasfitter provided the link that brought Edward to London.”

“I presume that the dagger was found.”

“Yes, that night. Edward did not want to wait, and truth be told, neither did I. Clive, certainly an interested party by that point, would have put it off until morning, but he was outvoted. We caught a late train from Liverpool Street Station, and were standing on the bank of the stream before midnight.

“While we were traveling, a band of rough weather had been moving in, and by the time we arrived, the wind was moaning through the trees. You would have quite enjoyed the atmosphere, Watson, and could have certainly described the mood better than I. Nevertheless, we equipped ourselves with a brace of dark lanterns and crowbars from one of the out-buildings, set off across the estate toward the stream, and soon found the stone in question, right where it was memorialized in the painting. There is no doubt whatsoever that Clive had been right, and we should have waited until morning. But in spite of the wind and threat of rain, and finding no other way but to wade into the stream, it was a relatively straightforward procedure, once we found the rock in the dark, still covered with the horizontal markings, although somewhat effaced by sixty years of stream flow and weathering.”

“The stone was leveraged out with ease, and Edward had the honor of reaching into the resulting void, giving a satisfied gasp as his fingers closed upon something.”

“Not exactly ‘Beside the Boulder’, was it? More like ‘Behind the stone’.”

Holmes grinned. “Richard was working with letters that would translate into vertical and horizontal components. The letter ‘n’ in ‘behind’ and ‘stone’ would have been problematic.”

He took a sip and continued. “As I was saying, Edward reached into the cavity and pulled out an oilskin packet, tied with rotting leather thongs, somewhat less than a foot in length. He started to open it right there, but then stopped, insisting that it should be his father who did the honors. There was no question but that we would join him, so we trooped back to the house and, in spite of our muddy and wet clothing and the old man’s nurse’s attempts to stop us, woke William up. Edward explained what had happened and how, and then, with reverence, placed the bundle in the old man’s hands.

“William Cavenham’s hands shook as he started to untie the thongs, whether from age, illness, or excitement, I could not tell. The old leather quickly crumbled away, and he proceeded to unwrap the cloth, first bound up over six decades before by his father, whom he never knew. There, in the flickering lights of his bedroom, quite likely the very bedroom where old Lloyd Cavenham had slept so many years earlier, the dagger was returned to the family.

“It was a curious thing – about nine inches in length, made of some dull alloy, and with a few awkwardly cut jewels pressed into it here and there with no apparent pattern. Ugly and plain as it was, however, it held a certain fascination nonetheless, simply knowing as we did whose it had been and some of the curious events surrounding it.

“It’s still there,” Holmes added, “if you want to see it. I’m sure they would be glad to show it to you.”

“And the canvas painting? What became of it? Grigsby said that it was lost.”

“It was destroyed in 1915, during a zeppelin attack that leveled Edward’s London house where he kept it. Sadly, Edward was also killed in the attack as well. He was in town, advising the Admiralty. Fortunately, his wife and son were at the country house in Bishop’s Stortford, and they were spared.”

We sat silently for a moment, recalling the terrible losses of just a few years before. I had never known Edward Cavenham, had in fact never heard of him until this past hour, but I was saddened at his passing nonetheless.

“‘From time’s flows…’” Holmes said, returning me to the present.

“What? From the poem?”

He nodded. “Obviously, it was a play on the fact that Richard had hidden the dagger beside a stream. He must have slipped back to bury it there while he and Lisette were staying in Montague Street. Not only did he commission the canvas version, along with adding the gold leaf to the plaster version, but he also chiseled the clue onto the rock. All of that effort, and for what? To tweak his father? To jeer at him? To use it as a lure so that they could reconcile?

“Imagine how his actions rippled the flows through all of those lives. He went to all of that trouble. He was right there at the manor house when he went to hide the dagger. What if he’d simply gone inside and talked to his father instead? The family might have been reunited right then. If he hadn’t gone to France, he mightn’t have caught the fever and died early, leaving his son to grow up without a father.” He shook his head. “Suppose the squabbles between the English and French hadn’t been so fierce just then, and Lloyd had been able to reach France sooner? And generations later, if a stranger hadn’t noticed two similar paintings in different houses, the mystery still might not be resolved. Each man’s path leads to so many possibilities, and they are so often fraught with perils.”

I had seen Holmes spiral around these maudlin thoughts of fate before. I recalled once when he discovered the identity of the murderer, only to find that the man had really had no other choice than to kill. “God help us!” Holmes had said at the time, after letting the man go. “Why does fate play such tricks with poor, helpless worms?”

I could see that his thoughts were leading him that way again. But, I decided, Not this day! I finished the beer and set the glass down firmly. “Any number of alternatives can always be spun out. What if I hadn’t been shot at Maiwand? Or what if the bullet had been an inch to the right or left? Your foot might have slipped on the ledge at Reichenbach. The Titanic could have sailed fifty yards to the south and been spared. Perhaps things would have been much different if Franz Ferdinand’s car hadn’t taken a wrong turn, placing him in Princip’s sight. Who can know?

“That type of thinking,” I continued, “is a pointless path that should be avoided.” I stood up. “No one can know the end results of all the turns of his or her life. One can only make the best choice possible from all the available data, and then face forward bravely, and be willing to adapt as well as possible when the time comes.” I gestured toward Museum Street, now starting to brighten as the noonday sun illuminated it and the last of the clouds burned away. “It is too beautiful a day to ponder one’s missteps or might-have-beens. I believe that you mentioned lunch at Simpsons?”

He pulled his thoughts back from wherever they had been going, looked up, smiled, and nodded. Joining me, we stepped away from our table and out through the side door. I took a deep breath of the summer air. Beside me, Holmes pulled on his ever-present deerstalker, worn year after year in spite of season and social convention. Then, gesturing ahead of him with his stick, he said – as he had done on that night so many years before when we’d stood on this very same spot, that time on the path of another man’s poor choices and a Christmas goose – “Faces to the south, then, and quick march!”

***

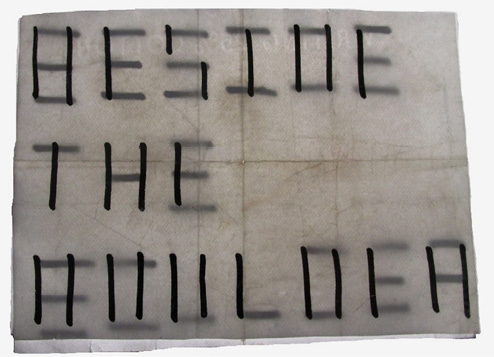

NOTE:

The painting in the parlor at No. 24 Montague Street, now a part of the Ruskin Hotel, is still on the plaster wall above the fireplace mantel, where it has been located for over two-hundred years. Sadly, as Sir Clive Bartleby predicted, the vertical gold leaf markings on the bottom right have long since flaked away. Fortunately, Watson’s notes upon the matter have survived.

“The Painting in the Parlor” - Photograph taken by David Marcum while staying at No. 24 Montague Street, (September 10th, 2016)