The Service for the American Colonel

I had returned to Baker Street that morning, after finishing my regular rounds, to change the dressing on Sherlock Holmes’s wound. He was up when I arrived, although I had expected that he might still be asleep, considering our late arrival in London the previous night.

He didn’t appear to be in any remarkable pain, and the wound looked clean with no prospect of permanent damage. He’d earned it when defending a young woman against the sudden rage of a cornered nobleman carrying an unsuspected knife. Holmes had easily disarmed the fellow, but not before his upper arm was slashed. The well-aimed butt of my own pistol had put the deviant on the ground, but even so, he began to recover much sooner than one might have expected – no doubt related to some extra strength he drew upon in relation to his previously disguised madness.

It was no surprise that our talk had drifted to speculation on the man’s fate. Throughout the series of murders which he had committed, there had been no signs of his insanity, but the gibbering and shrieking wreck that had been hauled away by Inspector Lanner would likely end up in the Broadmoor Criminal Lunatic Asylum rather than upon the gallows.

Our conversation had turned toward the concepts of criminal insanity and recidivism in general when there was a ring at the doorbell.

“As our discussion progressed, I neglected that we’re expecting a visitor.” He lifted a small note from the curious octagonal table beside his chair – a souvenir from one of those untold cases during his Montague Street days – and sailed it accurately in my direction. “This request for an appointment was waiting last night when we returned.”

I recognized the stationery used by the Langham. There was nothing remarkable about Holmes’s name and address scrawled on the front of the envelope – typical pen and ink. It was a man’s handwriting, firm and confident, perhaps a bit elderly. I said as much to Holmes, adding rather inanely, “He is right-handed.”

Holmes nodded, and as I heard steady solid footsteps beginning to climb toward the sitting room, I gave a quick glance at the note:

Mr. Sherlock Holmes,

I propose to call up on you at ten a.m. tomorrow morning if convenient to discuss a matter of fraud. Your name has been recommended to me by Inspector Lestrade of Scotland Yard, and also a man named Yves Paterson, from America.

Colonel H.B. Finn (Retired)

I looked toward Holmes. “Paterson was before your time, when I was in New York in ‘80, touring with Sasanoff. He was poisoning his wife with nutmeg – ”

Before I could learn any more about that intriguing incident, and with the realization that like so many others of Holmes’s early cases I might never convince him to share the details, there was a solid knock upon the door. Holmes bid the visitor to enter, and we stood.

Colonel Finn was a tall fellow in his early sixties, generally slim, but with wide shoulders, only just beginning to round a bit with age. His face was lined and long-darkened by the sun, and he had somewhat unhealthy circles under his eyes, as if a hard life was catching up with him, and he no longer lacked the strength to put up an opposing argument. He had big hands with large knuckles – clearly he had done much hard labor in his youth. His clothes were of an American cut, as were his boots, and well made – tailored and rather expensive looking. They weren’t old, but obviously they were comfortable friends. Hanging from one hand was a wide-brimmed western-style American hat, such as I had last seen just a year before during an extended sojourn in the United States – particularly in San Francisco, but with forays into other areas of the North American continent as well.

As was so often the case, visitors to Holmes’s sitting room inherently identified my friend as the man whom they were seeking. Finn glanced up and down Holmes’s lean figure, a smile crossing his face when seeing that my friend was still in his dressing gown, although otherwise clothed properly to meet guests.

“Colonel Finn?” confirmed Holmes. “Excuse my casual attire. Watson here had just finished changing the dressing on a wound received last night in noble combat.”

“Knife cut?” asked the American, his voice a growl, the accent containing a curious American twang. “I thought so. I saw the medical bag, open there on the table. You hold your arm as if it’s tender, but there isn’t any sign of a bulky bandage, such as one would pack around a bullet wound, and anyway your color is too normal for a man who’s been shot and lost a lot of blood.”

Holmes smiled. “An observant man after our own hearts, Watson! Most who cross that threshold, Colonel, are not nearly so eagle-eyed.”

“Nothing to it,” the man said gruffly. “I’ve been cut a few times myself, and so have others that I’ve known. Just a matter of recognizing what you’re seeing and making the right assumptions to be going on with.” He glanced my way, and Holmes explained my presence.

“This my friend and associate, Dr. John Watson. He is often involved in my investigations, and is invaluable during an investigation.”

Finn offered a hand to me and then Holmes. “That Inspector said you’d likely be here, Doctor. The more insight the better, I suppose.”

Holmes gestured the visitor towards the basket chair facing the fire, and Finn nodded, removed his overcoat, and laid it and the hat across the settee. I offered him coffee or tea, but amended the statement when he glanced toward the spirit cabinet. “Or something stronger?”

“Whisky, if you don’t mind,” he said. “I’ve been in worse weather than what England can throw at me in February, but as I get older, I feel the cold worse and worse.” He thanked me when I placed a glass containing a generous amount in his hand and settled into his seat. “Of course, I try and be careful – my own father was a drunk, you see, and I’m extra chary not to travel down that road.”

I understood, for my own brother was of a similar nature, and watching his long and steady self-destruction had been an object lesson of incredible, though tragic, value.

“You mentioned fraud in your note…” Holmes prompted, his tone encouraging elaboration.

Finn nodded. “Mind if I smoke?”

Holmes offered no objection, and decided to prepare a pipe for himself as well. (I declined.) Finn accepted Holmes’s offer of tobacco, raising a curious eyebrow when it was presented in the Persian slipper kept on the mantel, but he made no comment. He packed his own pipe – a curious corncob construction that I had seen used before in more rural parts of the United States, and said, “I came to England to acquire a work of art – although it’s more for sentimental reasons than it actually being any good. When I arrived, the dealer suddenly became coy with me – he didn’t quite have it in his possession after all, he said, but he might be able to get it, though it was going to cost me extra. There was another bidder, and so on and so forth. He didn’t know who he was dealing with, and rather than play his game, I walked around to the police. They’ve heard of the fellow – seems he has a reputation for this kind of thing – skirts right up to the edge of the law – but in this case he hasn’t done anything illegal – yet. But the inspector who talked with me – Lestrade – said that you might be able to get me some leverage.”

“Who is this shady dealer?” asked Holmes.

“A kind of a man called Swadlincote. He has a little shop in a place named the Lowther Arcade, on the Strand.”

Holmes smiled – not amused, but knowledgeable. “Mr. Lucius Swadlincote is in fact named Rufus Conger – a shining success story of sorts from the Rookeries near Seven Dials. It’s possible he actually has the artwork which you seek, but this would need to be ascertained to your satisfaction. What is the object?”

Finn shifted and his eyes narrowed. He looked up and to the left, as if he could see what he recalled. “A drawing –fifty years old, give or take. It’s – well, it’s hard to describe, really. Most would say it’s ugly, and amateur and raw, but that kind of thing has become popular of late. I first saw it when I was a boy, and over the years I never thought of it as anything but an unsettling peculiarity at best. In the last year or so, thought, things like that have become popular, and in spite of how bad it is, somehow this artwork became known and collectible.

“I’m getting old, and have more money than I know what to do with – my children are comfortable, and they don’t need all of that burden settled on them. I’ve spent some of my fortune in some good ways, and some not so good, but the last few years I’ve had extra cause to be reminded of my misspent youth, and to become sentimental about it, and this drawing is a part of that. I decided that I could afford it – and other works by this dead artist too – and wanted to buy it, and the road led to the Swadlincote feller.”

Something about the man’s story sounded vaguely familiar, and I asked for additional information. “Could you describe the drawing?”

“I can, but perhaps I should lay a little more groundwork first.” He raised his glass, let pipe smoke flow from house mouth across the glass of whisky, and took a sip. He licked his lips, and then judged how much of the amber liquid remained. Then he tightened his mouth as if making a choice and set aside what was left – more than half of what had been provided to him – abandoned on the side table. He didn’t drink any more of it during the remainder of his visit.

“When I was a boy, just fourteen or fifteen, I was no account. I was raised in St. Petersburg, Missouri, on the banks of the Mississippi. My mother was long dead, and my father – as mentioned – was a drunk. The town drunk, as a matter of fact.

“I lived as I pleased, friends with some of the other children my age, while others shunned me. In fact, I was either hated or dreaded by all the mothers of the town, as they thought me idle and lawless and vulgar and bad. It was for this reason that I was admired so by the other children – they delighted in my forbidden society, and wished to be like me.

“I was always dressed in the cast-off clothes of full-grown men, and they were in perennial bloom and fluttering with rags. My hat was a vast ruin with a wide crescent lopped out of its brim, and my coat – when I wore one – hung nearly to my heels and had the rearward buttons far down the back. One suspender supported my trousers, and the fringed legs dragged in the dirt when not rolled up.” He gestured at his current costume. “Not like now, you see. I came and went at my own free will. I slept on doorsteps in fine weather and in empty hogsheads in wet. I didn’t have to go to school or to church, or call any being master or obey anybody. I could go fishing or swimming when and where I chose, and stay as long as it suited me. I wasn’t forbidden to fight, and I could sit up as late as I pleased. I was always the first boy that went barefoot in the spring and the last to resume leather in the fall. I never had to wash, nor put on clean clothes – and I could swear wonderfully. In a word, everything that goes to make life precious I had. And I tell all of this to explain why I left St. Petersburg.

“I had lived wild and free for so long that when a local widow took me in and tried to ‘civilize’ me, I nearly couldn’t stand it. Finally, when I had a chance to leave town and help a friend – and in truth, what I was doing was trying to help him escape to the north, for he was a slave of long acquaintance – I took it. We wandered from place to place, riding a raft when we were able. At one point we were separated for a few days, and I was taken in for a time by the Grangerford family.

“They were a curious bunch – wealthy enough for that area, and locked into some sort of blood feud with their neighbors. But they cared for me when I needed it, and for a few days I was able to live in their house and see their ways.

“They’d had a daughter who had died sometime before I arrived– Emmeline Grangerford. She was only fifteen years old at the time of her death, and she’d made quite an impression on the family when she was alive, because the whole house was a tribute to her now that she was dead. She’d written up all sorts of poems and produced a shocking amount of black charcoal drawings – all related to some sort of heartbreak or tragedy or death. I supposed that it was only fitting that such a one as she, who was so fascinated with dying, should be taken early.

He puffed the pipe, and then continued. “They called her drawings ‘crayons’, and had them hanging all over the house. They were different from any pictures that I’d ever seen before – blacker, mostly, than is common. One was a woman in a slim black dress, belted small under the armpits, with bulges like a cabbage in the middle of the sleeves, and a large black scoop-shovel bonnet with a black veil, and white slim ankles crossed about with black tape, and very wee black slippers, like a chisel, and she was leaning pensive on a tombstone on her right elbow, under a weeping willow, and her other hand hanging down her side holding a white handkerchief and a reticule, and underneath the picture it said, ‘Shall I Never See Thee More Alas’. Another one was a young lady with her hair all combed up straight to the top of her head, and knotted there in front of a comb like a chair-back, and she was crying into a handkerchief and had a dead bird laying on its back in her other hand with its heels up, and underneath the picture it said ‘I Shall Never Hear Thy Sweet Chirrup More Alas’.

“There was one where a young lady was at a window looking up at the moon, and tears running down her cheeks, and she had an open letter in one hand with black sealing wax showing on one edge of it, and she was mashing a locket with a chain to it against her mouth, and underneath the picture it said ‘And Art Thou Gone Yes Thou Art Gone Alas’.

“These was all nice pictures, I reckon, but I didn’t somehow seem to take to them, because if ever I was down a little they always give me the fan-tods. Everybody was sorry she died, because she had laid out a lot more of these pictures to do, and a body could see by what she had done what they had lost. But I reckoned that with her disposition she was having a better time in the graveyard. She was at work on what they said was her greatest picture when she took sick, and every day and every night it was her prayer to be allowed to live till she got it done, but she never got the chance. It’s this picture that I’m here to buy.

“After I left the Grangerford house, I re-established myself with my runaway slave friend, and we continued our journey. Eventually I ended up staying with a kind old woman for a while before I started to feel strangled again, just as I had when the widow had tried to adopt me, and so I lit out for the Territories.

“I did a lot of wandering out there, and made fortunes and lost them. I was in the Mexican-American War, and met a lot of those officers that would later be on both sides of the Civil War. A year or so later I was a Forty-Niner in California. That’s where I got rich the first time. I was married for a time then to a widowed school-teacher who showed me the value of education in a way that I never grasped as a boy. Later, after she died, I drifted some more. I was with the anti-Slavers and abolitionists in Kansas in the 1850’s, and by 1861 I had made it to Virginia City, Nevada, where I made my second fortune on the periphery of the bonanza at the Comstock Lode – I was too smart to mine, but I knew from my California days that money could be made supplying the miners. For a time there I was good friends with a former sea captain named Ben that I’d met years before in my travels – he’d since established himself near Virginia City with a massive ranch, which he owned and defended with the help of his three grown sons, each from a different mother, and all of them as different from one another as night and day. I used to go to his ranch often for the conversation and an evening meal – he had a most talented Chinese cook. It was at one of Ben’s dinners where I was introduced to a newspaper fella who was working then in Virginia City.

“I became thick with that feller – name of Sam – and ended up telling him a whole passel of stories about my days as a youth. After that we lost touch with one another – he went his way, and I went back east and served in the Army – for the North to preserve the Union and free the slaves, mind you. That’s where I picked up the rank of Colonel. It isn’t an honorary thing – I did a fair bit to earn it in Knoxville campaign and the battle at Chattanooga. Then I went west again and settled in Santa Fe, where I took sides with the Mora Gunfighter. I still live there when I’m not gallivanting all over. Twelve years or so ago, Sam from Virginia City tracked me down again to ask more questions about the tales I’d shared, and he ended up writing a couple of books based on what I told him – with my permission, of course. The first of them came out in ‘76, and the other just a few years ago, in ‘84.

“It was that second book that had a bit about my descriptions of Emmeline Grangerford’s peculiar artworks and poetry. Nothing came of it then, but last year when that other poet, Emily Dickinson, died, there was a sudden interest in that kind of poetry – a terrible fascination with death that woman had. Someone remembered reading what I’d said in that book by Sam and tracked down the Grangerford family, looking for Emmeline’s old art and poems. By then, all the Grangerfords that I’d known were long dead, mostly killed by their neighbors, I reckon, if the War didn’t get them, but what was left of the current generation still had all of that girl’s scratchings stored away in a box, and they sold it lock, stock, and barrel to a New York art dealer. He worked up a real frenzy about all of it – a true nine-days’ wonder – and when all that happened, my friend Sam sent me a letter, thinking I might be amused.

“I was, but more than that, I also became interested in buying some of it – and eventually all of it – more for sentimental reasons about my long-gone boyhood than any belief that there was anything good or talented about what Emmeline wrote and drew. I’ve read that some people thought she was a genius, cut down before her prime. And I recall at the time – when I was fourteen or so – that I thought that if she could make poetry like that before she was fourteen, there was no telling what she could have done by-and-by. They said she could rattle off poetry like nothing, and didn’t ever have to stop to think. She would slap down a line, and if she couldn’t find anything to rhyme with it, she’d just scratch it out and slap down another one, and go ahead. She wasn’t particular. She could write about anything you choose to give her to write about, just so it was sadful.

“Every time a man died, or a woman died, or a child died, she would be on hand with her ‘tribute’ before he was cold. She called them ‘tributes’. The neighbors said it was the doctor first, then Emmeline, then the undertaker – the undertaker never got in ahead of Emmeline but once, and then she hung fire on a rhyme for the dead person’s name, which was Whistler. She wasn’t ever the same after that, they’d said. She never complained, but she pined away and didn’t live long, poor thing.

“Over the last year or so, I bought one of her drawings, and then another and another, and the poems too. I have all of those that I mentioned, and a number of others besides – the dealers and critics are calling them Emmeline’s ‘Alas’ series. I’m afraid that it’s became something more than a hobby to me lately, filling up my time as I track down what I don’t have. My last wife died a couple of years ago, and my children are scattered, so I have nothing much else to do, and as you’ll know, gentleman, collectors are the strangest sorts of cats. How else to explain that I hope to acquire Emmeline Grangerford’s complete works? And I’m very close to doing it.

“Word went out that I was the man to beat when collecting Emmeline Grangerford art, and that has led to the prices on what’s left going up – knowing I can afford it – and me receiving messages from dealers all over offering items that I wasn’t even chasing quite yet. One such was from a man here in London, a private individual named Potter, who had one of Emmeline’s handwritten poems, “Ode to Stephen Dowling Bots, Dec’d’, about a lad who fell down a well and drowned. When I learned about the drawing offered by Swadlincote, also here in London, I sent a message to him indicating that I was going to be over here anyway, and would like to purchase what he had for sale. That was a mistake, I guess. It let him know my interest, and gave him time to find out more about me – and just what I could afford. By the time I got here, he’d decided to chisel me for whatever else he could get. And so here I am.”

Colonel Finn’s story had been in more depth than Holmes will usually tolerate, but he seemed to be enjoying the story, and he’s always had a unique fascination with and affection for Americans. For my part, suspecting who our visitor was, I was quite happy to hear the man’s narrative.

“Tell us of the drawing you’re here to acquire,” said Holmes.

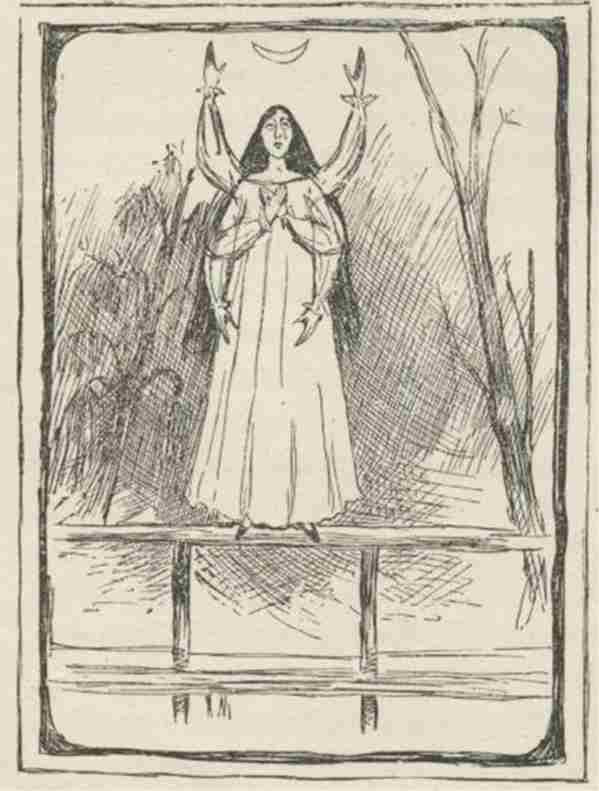

“Well, as I said, it was the drawing Emmeline left unfinished when she died. It was a picture of a young woman in a long white gown, standing on the rail of a bridge all ready to jump off, with her hair all down her back, and looking up to the moon, with the tears running down her face, and she had two arms folded across her breast, and two arms stretched out in front, and two more reaching up towards the moon – and the idea was to see which pair would look best, and then scratch out all the other arms. But as I was saying, she died before she got her mind made up, and afterwards the Grangerfords kept that picture over the head of the bed in her room, and every time her birthday came they hung flowers on it. Other times it was hid with a little curtain. The young woman in the picture had a kind of a nice sweet face, but there was so many arms it made her look too spidery, seemed to me.”

I laughed, and Colonel Finn nodded good-naturedly. Holmes had a raised eyebrow, as if contemplating why such a work as described would ever solicit a single jot of interest, even for sentimental reasons. And yet, some of the items that he keeps – from a rudely framed and unfocused photograph of Charlie Peace on his bedroom wall, to the carefully shaved and shaped femur of a Neolithic man – which he desperately carved into a dagger as a boy to defend himself against an unexpected rabid dog (or so I’m told) – seem just as unusual when considered in the cold light of dawn.

Holmes set aside his pipe. “Your story has some features of interest, but I must honestly tell you that normally it wouldn’t be the sort of case I’d take. Finding ‘leverage’, as Lestrade suggested I might do, for one man to use against another in a business dealing is outside the normal self-described limits of my practice. However, I am familiar with Mr. Swadlincote, and this is an excuse to pry into his affairs a little bit, for I’ve neglected him for too long. You’re staying at the Langham, I believe?”

Colonel Finn nodded.

“Excellent. Watson and I should have something to report within a day or so. In the meantime, a message regarding any new factors connected to the problem will find us here and will be much appreciated.”

Finn nodded again and pushed himself to his feet. “That’s all that I can ask, then,” he said. “I normally take care of my own business, but I’m a stranger here, and haven’t had a chance to get the lay of the land.” And with that, he offered his hand to both of us and made his departure.

When he’d gone, I tossed the remains of whiskey into the fire, causing it to blaze forth a satisfying but very brief flash before setting the glass on the dining table for later retrieval by Mrs. Hudson. Finn’s story sounded quite familiar, and I wanted a chance to conduct a quick bit of research, but instead I asked, “What are your plans? Do you intend to see this Swadlincote in Lowther Arcade?”

“I don’t think that would be advisable,” was Holmes’s reply. He had dropped back into his chair after Finn’s departure, where he continued to smoke, an unusually concerned look upon his face.

“Is this more serious than I thought?” I asked.

“It is indeed. Swadlincote, originally named Conger, is one of the lower-tier agents of the Professor, and as such, I must be careful in how I express my interest in this matter.”

At that time, in early 1887, Holmes had been aware for quite a while of the organization constructed by Professor Moriarty, later to have such an infamous reputation. But then, the Professor seemed to most observers to be living a quiet life as an army coach, having come down to London a few years earlier from one of the university towns, where he had been compelled to resign his chair after dark rumors gathered around him. Holmes had known him in his own university days, and initially he had been resistant to believe that his old math tutor could be responsible for the unifying criminal web that was slowly being constructed in the capital. Eventually, however, the evidence could not be ignored. And yet, he was still having a most difficult time convincing the authorities of the truth, while each day the web grew more complex and its grip tightened stronger.

In those days, Moriarty was not quite the notable criminal of just a few short years later, and neither was he yet as bitter as he would specifically become toward my friend. Then, it was almost as if they were playing some sort of chess game, constantly testing and trying to guess the strategy and resources of one another, although Holmes was never complacent or amused. Only after the professor’s injuries a few years later following a fall from the Tower of London (when attempting to steal the Crown Jewels while disguised as a constable) did the game become grim and deadly.

“Swadlincote knows me,” said Holmes. “I would prefer not to appear as myself in this matter. But perhaps, Watson, I could enlist you to be my representative?”

“I would be glad to assist in any way.” Suspecting Finn’s identity made me all the more willing to be involved in the affair.

“Then I see you acting as a competing buyer – having heard of this rather dodgy-sounding piece of art, you can present yourself at the shop and see if our man is open to a bidding war between you and the Colonel.”

“Won’t that have an adverse effect for your client?” I asked. “If the dealer believes there’s more interest, he’ll raise the price even higher, so that when Finn does complete the arrangements – assuming that this dealer even has the drawing – he’ll have to pay an excessive amount beyond what’s being asked now. It seems as if you’re asking him to cover an extra cost just so that you can carefully probe the Professor’s organization from a distance.”

“Not at all. While you approach Swadlincote, I’ll refresh my memory on his associations with the Professor, and determine just how deeply he’s involved. We should be able to use the ‘leverage’ Lestrade mentioned to get the drawing for Finn while finding some new and useful fact that will be of use in the future. And there’s always the chance that our sudden interest in Swadlincote, coming from an unexpected direction, will be like suddenly turning over a rock and sending what lives beneath it scurrying around helplessly in the bright sunshine.”

“Shall I go over there, then?”

“Not quite yet. First, do a few hours of preparation. Go see your friend Lomax, and have him give you information about the current interest in this sort of art. Perhaps he can tell you more of Emily Dickinson, mentioned by the Colonel, to give you a frame of reference when talking over the Grangerford drawing. I’ve found that just a little knowledge of art can be spun into a lot of convincing moonshine, with the right attitude. In the meantime, I’ll carry out my own inquiries, and we’ll meet back here in a few hours.”

And so I set off for St. James’s Square, and the London Library, where I knew that Lomax, the sublibrarian, could be found, regardless of the season or the time of day. And so he was. I explained a bit about my mission, without getting into specifics, and that I needed to have some frame of reference when talking to the dealer. Like all good librarians, he let me ask about what I thought that I needed, and then, through a few intelligent and defining questions, discovered what I really needed. He had some knowledge of this new interest in the type of poetry that had been popularized by the recently deceased Emily Dickinson, but said that I’d be better off finding out about Susan A. Moore, an American whose volume The Sentimental Song Book had been published in 1876, and seemed to feature much the same type of verse as that of the long-deceased Emmeline Grangerford.

Of course, Lomax had made sure that the London Library’s collection had acquired a copy, and he pressed it into my hand, noting that no one had checked it out since the book had been acquired over a decade before.

I stepped outside, where I read one of the pieces at random, entitled “Little Libbie”:

One more little spirit to Heaven has flown,

To dwell in that mansion above,

Where dear little angels, together roam,

In God’s everlasting love.

With an expression on my face that might seem as if I’d inadvertently walked through a floating miasma of passing sewer gas, I snapped the small book shut, muttered something about “Ineffable twaddle!”, and walked into Pall Mall to find a hansom cab for the ride back to Baker Street.

I hadn’t been gone as long as I might have thought, and so I settled in with a cup of hot café noir as provided by the indefatigable Mrs. Hudson and read through as many of the other poems as I could tolerate. One referred to a dead man sleeping and resting in peace in a cold silent tomb. I scanned down the six stanzas and decided that I had no need to reach the end. Another concerned the death of a girl – one of nine children – who was now waiting for her siblings in heaven. While it wasn’t necessarily bad, it was doggerel of the type that I simply could not enjoy. And yet, I suspected that it was written at the time as a comfort to a family known by Moore who had lost a daughter, and it was surely heartfelt and sincere, if unpolished. Certainly Emmeline Grangerford’s own poems, as described by Finn, had been written with the same intent – to act as “tributes” to provide honor and comfort to grieving families. In spite of my own failure to enjoy this type of thing, and even an initial impulse to ridicule, I couldn’t fault the intent, and I found that I was apologizing a bit to Mrs. Moore, wherever she might be, for initially and harshly judging her work – albeit without her knowledge.

Holmes arrived an hour or so later, and I could somehow sense that it had gotten colder outside. I recalled seeing the high icy clouds pushing in from the west, and wondered if the morrow wouldn’t bring some rather unpleasant weather.

After hanging his Inverness and fore-and-aft cap, Holmes poured himself a cup of coffee from the pot left by Mrs. Hudson, certainly cool by now, and joined me by the fire. Rather than tell me of his own efforts, he had me summarize a bit what I’d learned from Lomax. Then we began to discuss a strategy whereby I could present myself at Swadlincote’s shop – ideally later that afternoon – and open my own fraudulent negotiations for the curiously unappealing Grangerford artwork.

Holmes was discussing how I could bluff my way into seemingly having enough knowledge of the subject to interest an unscrupulous dealer when the doorbell rang. Within a moment, we heard the steady and heavy tromp of boots regularly climbing the stairs, and both of us knew it could only be a policeman.

It was – Constable Wilkins, whom we both knew of old. “Gentlemen,” he said, speaking formally and carefully while touching his helmet with a finger. “Compliments of Inspector Lestrade, he asks if you might return with me to the Lowther Arcade. There has been a murder, and the man who seems to be responsible – an American – is in custody there and asking for you both.”

Holmes’s lips tightened and he shook his head – not a refusal to accompany the constable, but rather an expression of irritation. It seemed that our plans had been disrupted, or negated completely.

Wilkins had a growler waiting, and we were soon making our way through the surprisingly busy streets. I asked about the weather, and the constable confirmed that a winter storm was on the way – perhaps explaining why so many Londoners were out and about that afternoon, as they took care of business before the need to possibly hide away for a day or so. I pulled my heavy overcoat tighter.

When the inane conversation was complete, Holmes leaned forward like a bird of prey and instructed Wilkins to provide particulars about the murder to which we traveled. Having known one another for quite a while, the policeman complied as if answering to one of his own inspectors.

“The dead man is an art dealer, Lucius Swadlincote. He has a shop about halfway through the Lowther Arcade. Inspector Lestrade said that he was asked about this very chap only this morning by an American – the same one who was found beside the body, unconscious, and with blood on his hands.

“Both of them were in the back room, which seems like a small office. The dead man was in his chair, his throat cut, and the American – a Colonel Finn – was on the floor beside the desk. The back of his head has a lump, and he was unconscious when we arrived – or at least he was pretending to be. Mrs. Swadlincote had been out – she sometimes serves as something of a clerk there, she explained – and when she returned from a visit to see her sister in Touchen-End, she found her husband dead and the American lying on the floor. She ran out screaming until Constable Wilson heard her. He whistled, and it wasn’t long before the Inspector and I were there. After all, it isn’t far from the Yard, is it?”

By then we had arrived. The driver pulled to a stop in Adelaide Street, by the path leading through to St. Martin’s Church. We could see that word of the murder had already spread, as a motley crowd of loungers was clustered around the entrance to the Arcade. Several seemed to recognize Holmes, as they pointed and whispered. One man – a fellow named Alfred Bassick – was familiar to me. He was a trusted member of that small squad of Professor Moriarty’s lieutenants, and when our eyes met, he awkwardly ducked his head and turned away, as if looking elsewhere, and then crept away. He knew that I had recognized him.

We passed through the crowd, and in the short space between the entrance and Swadlincote’s shop, where a number of policemen were clustered, I shared that piece of intelligence with Holmes. He nodded, and then we were shown into the presence of Lestrade and a small taciturn woman, deeply grooved lines on either side of her bitter mouth, each standing by a counter, upon which several sheets of paper were spread. At the side of the room was our client, Colonel Finn, sitting in a chair while a constable stood behind him. He flashed a rueful smile on his face when he saw us, and he shrugged as if to apologize.

Holmes joined Lestrade, who led him to the office door to view the body, while I walked over to Finn. The constable behind him, Burnsall, had been along the previous autumn when Holmes and I had revealed the secret tunnel leading to the counterfeiter Malham’s presses, so he wasn’t concerned when I offered to check Finn’s head.

“I’d been to the other dealer to complete the purchase of Emmeline’s poem about that Bots feller, and even though I’d spoke to you and Mr. Holmes just an hour or so earlier, I didn’t see any harm in sending a note that I’d be stopping by. I didn’t let on about our earlier pow-wow. I just asked if he’d had any luck in tracking down the drawing. When I arrived, he said that he’d found the drawing – which would mean that what we discussed earlier didn’t necessarily matter anymore – and then he took me there to his office. It’s a small room, barely big enough for him to squeeze around and behind his desk, so I stood in the doorway. I was watching as he bent down to open a desk drawer when everything went dark. Someone hit me from behind while I was standing there. When I woke up, the police were here, the man was dead, and there was blood on my hands.” He held them up, but I could tell that he’d since been allowed to wipe them clean.

I observed that, while Finn had a sizeable lump upon the back of his head, he wasn’t in any serious danger, provided that we kept an eye on him for possible concussion. As I straightened up, I realized that the others in the room had fallen silent and had been listening to his statement.

Lestrade beckoned me closer. “Is it possible, Doctor,” he asked sotto voce, “that the wound on his head could be self-inflicted? His story doesn’t make any sense. He told us that when he arrived, it was only him and Swadlincote in this room, and it was just a moment later, only a few footsteps away, that he was standing in the office door when he was struck behind. He claims that Swadlincote was alive up to that moment, but he awoke to find us here, standing over him, and the dealer dead. And Mrs. Swadlincote says that when she walked in, she saw the door to the office standing open – it’s normally kept closed – and the Colonel lying there. She could see her husband past him, dead in his chair. That’s when she went out and summoned the police.”

“He killed him!” the woman shrieked, surprising us all after the low tones from the inspector. “He’s been pestering him to death about the awful drawing, and acting as if he didn’t believe that Lucius was doing everything he could to find it. Now what will I do? How can a woman like me carry on with such a business? My livelihood is ruined!”

She evinced a hardness that left no surprise when she didn’t seem to care that her husband was dead, other than how it affected her economic prospects. Holmes, however, only seemed to be half-listening. He looked my way. “What say you, Watson?” Could he have faked the blow to his head?”

“I don’t see how. It appears to be from some object – and I trust that no such thing was found beside him, dropped by his own hand.”

“No,” agreed Lestrade, “but he could have hit himself with something – one of these knick-knacks on the shelves – and not knocked himself unconscious, but instead replaced it and then lay down on the floor until someone arrived.”

“But why do that?” asked Holmes. “He had no reason that we know to kill the man, and if he did, why would he then stay and incriminate himself in such a manner.”

“He knew that he’d sent a note telling that he was coming,” said Lestrade, picking up one of the sheets on the counter. “This note, as a matter of fact.” It looked to have a few drops of blood across it.

“Where was it?” asked Holmes.

“Lying on top of the dead man’s desk.”

“So again, the flimsy case you build makes no sense. The Colonel sends a note, and then subsequently arrives and is told that the drawing has been found – I believe that the drawing is also there on the counter, based on how it was described – and then for some reason he then decides to cut Swadlincote’s throat. Instead of gathering up the drawing and the note indicting that he’d be visiting here, and then making his escape, he hits himself on the head with a curio, replaces it, and then lowers himself to the floor to await the inevitable arrival of the authorities. No, Lestrade, it won’t do.”

He turned to the dead man’s wife. “Did you know of the note sent by the Colonel?”

“No,” she answered, almost immediately by “Yes!” She seemed prepared to speak further, but Holmes nodded and then stepped into the small office to examine the body. I glanced through the door to see that dead man, originally named Rufus Conger, was leaned back in a chair behind the desk. The room was quite small, not more than eight feet square – really more of a storage closet. The room opened to the left beyond the door, with shelves on the right wall running to the back, and the desk pushed over against the left wall. There was a chair in front of the desk on the door side, and Swadlincote’s own chair at the back of the room, with a number of boxes stacked haphazardly around it. The dead man was a balding and puffy man in his fifties, and he had a shocked expression on his face. The gaping wound on his throat, a terrible cut that resembled an upturned red smile, had spurted a gout of blood across the desk, and had then continued to flow down his shirt.

Leaving Holmes to his examination, I looked at the documents on the counter. Besides the note written by Colonel Finn, indicating that he would be by that afternoon to check on the progress in locating the dead girl’s drawing, there was the illustration itself, about a foot high and nine inches wide, on thick yellowed paper, the kind often used for amateur sketches. Finn had said that the drawn figure appeared to be on the railing of a bridge, although I could not confirm it. She was on a railing of some sort, but if it was a bridge, the water was very high, as the posts seemed to be reflected into the water just beneath where she stood, and there was no indication of the bridge’s deck. Something like a crescent moon was just above her head, but pointed up on each end in the way that a child would draw a smile. It terribly reminded me of the gash on Swadlincote’s throat.

There was a dead-looking tree on the right of the picture, and quite a bit of hatching back-and-forth darkening the background behind the central figure, a young woman in a long white dress, with her tiny pointed feet sticking out beneath her on the bridge rail, and her long black hair hanging behind her and fanned out, visible on both sides. Her long weary-looking face was actually rather well executed, and she seemed to be looking up toward the sky – possibly toward the smiling moon that hovered over her. As Finn had described, she had three pairs of arms, one set held heavenward, one grasping in prayer across her breast, and the third hang hanging down. Around the entire thing was a rough and crude blacked-in border. I understood that the artist, young Emmeline Grangerford, had passed before she could complete it and choose which set of arms to keep, but in some way, all of the arms seemed to convey a message – although I couldn’t quite express it. In any case, I was not repulsed, but neither was I interested enough to see it as any more than the sketching of a moderately talented child. I certainly couldn’t understand the desire to collect it.

Beside it was third document, a sheet of old and yellowed copy-book paper. It was a hand-written verse with the curious title Ode to Stephen Dowling Bots, Dec’d. Picking it up, I looked toward Finn. He nodded. “That’s the poem I came over here to buy from the other dealer. The inspector took it from me when I was searched.” He scowled, and I held it a little more carefully, not quite sure what such an item cost, but certain that it was overpriced to the point that I ought not to damage it. Having seen Miss Grangerford’s illustrative talents, I held it closer to read how she set about writing a poem:

And did young Stephen sicken,

And did young Stephen die?

And did the sad hearts thicken,

And did the mourners cry?

No; such was not the fate of

Young Stephen Dowling Bots;

Though sad hearts round him thickened,

‘Twas not from sickness’ shots.

No whooping-cough did rack his frame,

Nor measles drear with spots;

Not these impaired the sacred name

Of Stephen Dowling Bots.

Despised love struck not with woe

That head of curly knots,

Nor stomach troubles laid him low,

Young Stephen Dowling Bots.

O no. Then list with tearful eye,

Whilst I his fate do tell.

His soul did from this cold world fly

By falling down a well.

They got him out and emptied him;

Alas it was too late;

His spirit was gone for to sport aloft

In the realms of the good and great.

Having now seen and judged it, and as a man with a vastly different set of priorities about what was good and what was not, I replaced the sheet on the counter, uncovered.

As I did so, Holmes stepped out of the office, carrying a bloody knife – looking something like a kris that I had seen in my soldiering days, and not an unusual artifact considering the similar items littering the small shop. “It was on the floor beside the body,” Lestrade explained.

Holmes laid the knife, which he held delicately by two fingers, on the counter, a distance away from the three documents. I could see that the blood was still damp. Then he continued to the front door, where he spent a moment opening it and closing it, fast and slow, sometimes from inside, and sometimes in the Arcade, while a couple of constables standing out there watched curiously. When he was finished, he returned to stand beside us. Looking at the small bitter woman standing alongside the inspector, Holmes said, “Sadly, it’s impolite to ask if I can inspect your shoes. May I instead have a look at your cuffs?”

Mrs. Swadlincote started to extend her arms, and then abruptly dropped them to her side. Holmes nodded as if it was expected. “No matter. I understand you’d been to visit your sister in Berkshire?”

“Yes,” she said with tight lips.

“And when you arrived back here, you discovered the body? And once you saw it, you turned and left the shop, screaming for help?” Again she agreed, warily.

Holmes turned to look past her at Colonel Finn. “What time did you send your note to indicate you’d be stopping here?”

“Around two o’clock. I paid a lad at the Langham to run it over while I had a late lunch.”

“Both facts that can be verified. What time did you arrive here?”

“A little before three.”

“And you came by cab?”

“I did.”

“It should be easy to locate the cabbie that brought you, fixing the time you arrived.” Holmes turned back to Lestrade. “The cabbie is likely one of those who frequent the Langham. What time was the alarm given?”

“A bit after three o’clock.”

Holmes nodded and looked back at Mrs. Swadlincote. “But the train from Touchen-End by way of Windsor arrived at Paddington around one o’clock, about two hours before you said that you walked in that door. Assuming that you actually visited your sister there as described,” Holmes said, his tone becoming more clipped, “which will also be investigated, you returned to London well before your stated arrival at this shop to find your husband dead and the Colonel unconscious on the floor. What did you do in the meantime during those two hours?”

“I… I came straight here.”

“Careful, Mrs. Swadlincote – you are on treacherous ground now. You haven’t had time to see how these different threads are tangled. A moment ago, you seemed to have some confusion as to whether you’d seen the note sent by the Colonel. First you said no, and then yes. Which was it?”

She didn’t answer, apparently trying to see the value or danger of each choice. Holmes glanced at Lestrade. “You say that the note was found on the desk in the office?”

“It was.”

“And the first constable on the scene was told that Mrs. Swadlincote had arrived, saw the body, and then immediately turned and ran back into the Arcade to summon help – without entering the office.”

Lestrade glanced at the woman. “That was her story. But what difference does it make whether she was back in time to know or not to know about the note and the Colonel’s proposed visit?”

“Knowing ahead of time that the Colonel would be here gave her the knowledge that a suspect would be available for the police after she killed her husband.”

The woman gave a shriek then, attempting to lunge across the counter for the bloody knife, but she was too short to do so effectively and, unable to reach it, she was pulled back by Constable Wilkins, who was joined by another officer. They each held one of her arms as she violently struggled from side to side before abruptly dropping to her knees with a sob.

“I have an advantage, Lestrade,” explained Holmes. “You and I both knew that Swadlincote had criminal connections, but you may not be aware that he’s part of a larger and growing organization. Today, when Colonel Finn shared his story with Watson and me, and that he’d had dealings with this shop, I sent Watson to some research while I visited one or two of my acquaintances in the criminal fellowship. They were reluctant to provide me with a great many details, as this larger organization of which I speak has a long arm and very little tolerance for those who reveal its secrets. But these individuals owe me a thing or two, and know that I can be trusted.

“As I hadn’t previously shined too much light on Swadlincote, I was rather surprised to learn that he wasn’t as important as I’d first thought – although I know for certain what sort of business has been carried out in this shop and its value to that organization. But it all made sense when my second source explained that the husband lying dead in the other room was simply a figure-head, and a rather stupid one, while his wife – this woman – is the actual brains of the business, and she was the one who had gained both the attention and the respect of the larger criminal organization.

“It seems that she’s been marked down for greater things, and all that’s been holding her back was her husband, perceived as something of a jelly-fish who could not be trusted. Things have been coming to a head of late, and today when the Colonel’s note arrived – and she was certainly on hand to read it – she suddenly saw a way to rid herself of a useless husband and frame this American, afflicted with the collector’s mania and rather bothersome of late as well. What she didn’t know was that Colonel Finn had already chosen to involve me in the business.

“Mrs. Swadlincote came back early, as can be shown by the train times – if she really went to Touchen-End at all. Your men can ascertain that, Inspector. In any case, she was here in time to know about the Colonel’s note, saying he’d be along about three o’clock. She left the shop sometime before he got here, but soon after he arrived, she slipped back inside. My investigations of the door just now show that, if one is careful and knowledgeable about its workings, that door can be opened silently.” He looked toward Colonel Finn. “She wasn’t here when you arrived, was she?”

“Of course not.” The older man said, waving a hand. “As you can see, there’s no place for anyone to hide. I would have known.”

Holmes nodded. “Then she looked in from the outside – perhaps, Lestrade, you can find a witness in the Arcade who saw her standing there, peeping through the window. She observed where the Colonel was standing, slipped inside, and crept close enough behind him to knock him unconscious. Then, when her husband – seated in that cramped space behind his desk – asked what was happening and why she had done what she’d done, she stepped over the Colonel’s recumbent form, approached her husband, likely as if to show him something, and then cut his throat, using a knife from the shop and dropping it by the body. How else to explain how he seemingly let someone approach in that cramped space without any signs of disruption? He certainly wouldn’t have let the Colonel do so. Only someone he trusted could have stood so closely.

“I saw a few signs along the edges of the bloodstains on the floor behind the desk of a small foot. That’s why I mentioned examining the lady’s shoes. There was also a chance that a few drops of spurting blood might be on her sleeve, despite her care to avoid it or remove them before summoning the constable.”

Lestrade seemed to have some questions as he struggled to understand, but Holmes pulled him aside and they spoke in low tones, no doubt explaining further details of Professor Moriarty’s organization which he didn’t wish to share with the entire room. At that time, there was some skepticism in the official ranks about what was perceived by the Yard as this peculiar “bee in Holmes’s bonnet”, and his apparent idée fixe on the mild-mannered mathematics professor, but to his credit, Lestrade had already seen first-hand some of the Professor’s evil handy-work, and he took no additional convincing to understand what had occurred, and that the American colonel was simply a scape-goat drawn into the ugly business.

By the time Holmes and the inspector had completed their discussion, Mrs. Swadlincote had been led away, and her dead husband’s body was being loaded for removal to the morgue. Colonel Finn was on his feet, indicating that he’d had much worse injuries in his long and storied past, and that a bump on the head wasn’t going to slow him down, curiously adding that someone who was so incapacitated “might as well walk”.

He stepped up to the counter to retrieve the handwritten document chronicling the unappealing Ode to Stephen Dowling Bots, Dec’d. He carefully replaced it within a long leather wallet held in his coat, and then asked, “What about the drawing? I haven’t paid for it yet.”

Holmes stepped behind the counter, where he retrieved a stiff folder lying there that would protect the artwork. “I believe,” he said, putting the drawing inside, “that the Swadlincote enterprise is now defunct. Perhaps, if your conscious requires it, you can make a donation to the lady’s legal defense in exchange for this drawing, but I have no doubt that it, based on your association with it from so long ago, should stay with you, rather than being carelessly examined and then likely destroyed by whomever empties this shop.”

He glanced toward Lestrade, who looked surprised at being asked. The inspector raised a hand in agreement. “Take it, for your troubles. Mr. Holmes is right. If I was the one cleaning out the place, I’d throw it in the furnace.”

Holmes re-opened the folder and gave the thing a closer look. Then he shuddered and handed it across to the Colonel.

Lestrade saw to the locking of the shop door behind us, and then he and Holmes set off for Scotland Yard to explore the further aspects of the affair. I located a hansom to take Colonel Finn and me to the Langham. As we passed through the lobby, I asked that the hotel doctor join us upstairs. Then, in Finn’s room, I explained that the man had a possible concussion and arranged that he receive regular examinations over the next day or so. Finn growled about it, but agreed. After the doctor departed, I wanted to ask the American a number of questions, specifically related to his past, but I found that I was uncertain how to broach the matter, and more important, that I didn’t necessarily want to know the truth from the ideas that I’d assembled in my head about the man. I was awkwardly reluctant to know the truth about someone whom I’d thought to be fictional.

For I was certain that I knew who he was. I think that he knew that I was aware of it, and he was grateful that I chose to leave the matter unexplored. I congratulated him on his possession of the recovered artwork, gave him some more medical advice regarding his injury that I doubted he’d follow, and then departed. But before leaving the building entirely, I sought out a hotel employee who owed me a long-standing debt, being paid over the years in tiny increments, and obtained a look at the hotel register. I was right – the Colonel’s initials, “H.B.”, represented exactly what I’d surmised.

A decade later, during the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee in the summer of 1897, I was able to meet the American author, Samuel Clemens, when he was living in Chelsea, tarrying there after his world tour and living in temporary seclusion following the death of his beloved daughter the previous year. We had a chance during those days to have many a long and free-wheeling discussion, and I was able to confirm a number of other particulars regarding my suspicions as to the identity of the man whom Holmes always simply called “the American Colonel”, although my friend never once gave any indication as to whether he was also aware the man’s true and notable identity, and if he was, whether he realized its significance.

“These was all nice pictures, I reckon, but I didn’t somehow seem to take to them, because if ever I was down a little they always give me the fan-tods.”

Illustration from the original edition of “Adventures of Huckleberry Finn,” by Edward Windsor Kemble (1861–1933)

With many thanks to Samuel Clemens (Mark Twain) for a lot of fun…