The Tower of Babel

GENESIS 11:1–9

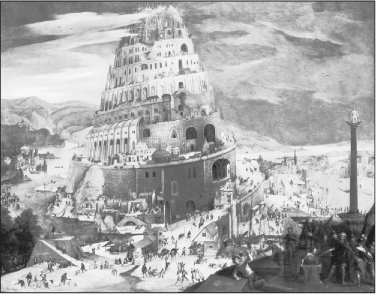

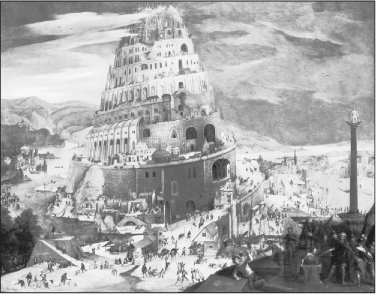

The Tower of Babel, 1604 by Abel Grimmer (1570–1619).

A TALE OF OVERREACHING. ZIGGURATS. DOWN WITH BIG CITIES. THE FIRST LANGUAGE SPOKEN BY HUMANS.

After the flood, Noah’s descendants continued to multiply; some reached the land of Shinar (Babylon). There they set out to build a great city with a huge tower, but God stopped them in the middle and scattered them all across the land.

The story of the tower of Babel occupies only a few verses in Genesis, but it seems to cover a great deal of territory.

Everyone on earth used to speak the same language and the same words. As people migrated from the east, they came upon a plain in the land of Shinar and settled there. Then they said to one another, “Let us make bricks and harden them with fire”—since they used brick for stones, and bitumen for mortar—and they said, “Let us build a city for ourselves, with a tower that reaches to heaven, so that we can make a name for ourselves and will not be scattered all over the earth.” But the LORD came down to inspect the city and tower that the people had built. Then the LORD said, “It is because they are one people and all speak the same language that they have been able to undertake this—in fact, nothing that they set out to do will be impossible for them. Let us go down and confuse their speech, so that they will not understand what they are saying to each other.” Thus the LORD scattered them from there all over the earth, and the building of the city was stopped. That is why it is called Babel, because there the LORD confused [Hebrew balal] the speech of the whole land, and from there the LORD scattered them all over the earth.

At the story’s beginning, all of humanity—descended from Noah and his family after the flood—is still a unified group; eight verses later, people are scattered all over the earth. With this scattering also comes the confusion, and profusion, of tongues; the one, universal human language is lost, ultimately to be replaced by thousands of different languages and dialects. Along with this, the human capacity for accomplishment undergoes a radical change: people go from unlimited potential—“nothing that they set out to do will be impossible for them”—to a state of disorder that prevents them even from finishing the city they had started to build. What went wrong?

The more that ancient readers of the Bible contemplated this question, the more troubling it became. After all, what was so bad about a bunch of people seeking to build a city? Surely the reason the Bible gave for this project—the people’s desire not to be “scattered all over the earth”—did not sound blameworthy in and of itself. Why, then, had God frustrated their plans and then sent them off in every different direction?

In seeking an answer, ancient readers eventually focused on the tower mentioned by the builders themselves: “Let us build a city for ourselves, with a tower that reaches to heaven.” Stipulating such a great height for the tower certainly sounded fishy. Perhaps, as so often, Scripture here was hinting in a word or two at some major point: the tower was the whole reason for God’s displeasure. After all, God is in heaven and people are on earth. It just did not seem right that humans should try to reach the realm of the divine, perhaps even challenging God’s heavenly rule in the process; the arrogance of this very idea must have been what caused God to frustrate their plans. Such a suspicion only seemed to be reinforced by the precise wording of the continuation of this text. The Bible said that God went down to earth “to inspect the city and the tower”; the latter specification seemed once again intended to indicate to readers that the tower itself had been the real sticking point.

As a consequence, ancient interpreters came to refer to this story not as the “City of Babel” but as the “Tower of Babel.” In fact, interpreters came to believe that behind this building project stood still more nefarious, if unstated, aims: the builders actually wished to enter heaven itself or to challenge God’s control of the supernal realm:

For they [the descendants of Noah] had emigrated from the land of Ararat toward the east, to Shinar, and . . . they built a city and the tower, saying, “Let us ascend on it into heaven.”

Jubilees 10:19

They were all of one language

and they wanted to go up to starry heaven.

Sibylline Oracles 3:99–100

[An angel said to Baruch:] “These are the ones who built the tower of the war against God, and the Lord removed them.”

They said: Let us build a tower and climb up to the firmament and strike it with hatchets until its waters flow forth.

b. Sanhedrin 109a

Read in such a light, the story seemed no less than a parable of human arrogance in general. Human beings ought to know their place, it seemed to say. Ingenuity and teamwork are fine so long as they do not lead humans to think too much of themselves—and too little of God. The great half-built structure of Genesis 11 loomed ever afterward in people’s minds as a model of what godless arrogance can lead to.

The Ziggurats of Mesopotamia

To modern scholars, the identity and significance of the tower are not all that mysterious. Almost as soon as archaeologists began to explore ancient Mesopotamia (modern Iraq), they came upon the ruins of various ancient structures, called ziggurats (more properly, ziqqurats), a kind of stepped pyramid that the Sumerians, Babylonians, and Assyrians built to honor their gods. Ziqqurats had become an essential feature of temple complexes in Mesopotamia as early as the end of the third millennium BCE. In all, archaeologists have uncovered the remains of some twenty-eight of them in Iraq and another four in Iran.

Since the area of the Tigris and Euphrates valleys did not feature large stone formations for people to quarry, the massive ziqqurats had to be built—just as the Bible reports—out of mud bricks (at first only sun-dried, but later fired in specially constructed kilns); the bricks were often stuck together with bitumen (a kind of asphaltlike substance). Because these materials are far less durable than actual stone, most of these ancient structures long ago collapsed into heaps of rubble—in fact, scholars believe that such collapses, especially of the ziqqurat façades, were probably not uncommon in ancient times. Thus, a biblical story about a great tower constructed in Mesopotamia—built out of baked mud bricks and bitumen, and perhaps one that was partially collapsed and subsequently abandoned—would certainly have rung true to any ancient Israelite who had traveled eastward to that great center of civilization.

At the same time, however, some modern scholars are skeptical about the emphasis placed on the tower by ancient interpreters.1 The tower is certainly there in the story—no doubt about it. But it is hardly the whole point. If it were, there would have been no need to mention the building of a city at all—let the project be limited to the offending ziqqurat! In fact, it is remarkable that, after God’s intervention, the text says, “and the building of the city was stopped.” Not a word is said about the tower’s fate; if it were so crucial, should not the text have mentioned its collapse or abandonment?

For such reasons, some scholars find the real point of this story to be neither the tower nor the universal “human overreaching” theme beloved by ancient interpreters. Rather, they say, the whole point is Babylon (babel in Hebrew). The thing that must have most characterized Babylon in the minds of ancient Israelites was its big cities with (for those days) their massive populations (“so that we will not be scattered all over the earth” was, it will be recalled, the builders’ justification for their project). From the standpoint of ancient Israelites, who were sparsely settled in the Semitic hinterland, such teeming conglomerations and the complex urban culture they made possible—including Babylon’s highly sophisticated religious practices, of which the ziqqurat was a fitting emblem—these things, the story seems to say, do not find favor with our God. In fact, long ago, He intervened and threw down one of those ancient towers of theirs just to show that all that pomp and filigree counts for nothing with Him. Precisely for that reason, the story adds, their country is known as Babel; this name does not derive, as one might suppose, from bab ilu (“gate of the god” in Akkadian), but from the Hebrew balal, since that is where God confused their speech to stop their urban building mania.2

Scholars differ about a possible dating of the story. Some say that an Israelite familiarity with Babylonian ziqqurats—and an Israelite interest in Babylon in general—is most appropriate to the period of the Babylonian exile in the sixth century; consistent with this date would be the depiction of Israel’s God as being active far to the east of His usual sphere of influence in earlier times. Others hold that neither of these arguments is decisive. An ancient Israelite in almost any period would certainly have known about the massive cities of Mesopotamia and their ziqqurats. As for the depiction of the deity in the story, they point out that His urging, “Let us go down and confuse their speech,” seems to bespeak the highly anthropomorphic God of earlier times, a God who moves from place to place and who is often surrounded by lesser members of His divine council (“Let us . . .”). Such a depiction appears inappropriate to the time of the Babylonian exile, when biblical texts tended to stress God’s immensity and His sole control of reality. Beyond such considerations, it has been noted that ancient Israel ultimately developed its own sophisticated urban culture; if this story is indeed a polemic against the Babylonian metropolis, perhaps its origins are to be sought in a very early time, when Israel might still remember itself as primarily a people of the sparsely inhabited Canaanite highlands. This was also a time when, scholars say, Israelite religion actually forbade the use of even a simple metal tool to quarry or shape the stones of an altar (Exod. 20:25)—a law that seems virtually to thumb its nose at the architectural sophistication of the Babylonian temple and ziqqurat. “All that Babylonian stuff,” this story seems to say, “is bunk.”

As with the story of Cain and Abel, the Tower of Babel narrative has, for modern scholars, certain clearly etiological elements: not only its explanation for the name Babel, but also its accounting for the dispersion of peoples across the ancient Near East and the replacement of an originally single, common language by an array of different, mutually incomprehensible idioms. Behind this latter element, too, modern scholars see a message not about the world as a whole, but something rather more local and specific. Semitic languages all appeared to be related: any native speaker could tell that Babylonian and Assyrian and Aramaic and Hebrew all had common roots and expressions, but a speaker of one tongue would not necessarily understand much of what was being said in the others. It is this reality, rather than the existence of different languages per se, that the story seems out to explain: all the peoples of the ancient Near East did, it says, originally speak the same language, but that unity was destroyed quite intentionally by God. (Some scholars think that such an etiological tale may have at one time existed quite separate from its current Babylonian setting, but that it was eventually combined with an independent story of arrogant Babylonians and their tower; others say the two elements were probably from the beginning part of the same story.)3

What, according to the Bible, was that original language spoken by all of humanity? The story itself does not say, but ancient interpreters, Jewish and Christian, were almost unanimous in the belief that it was Hebrew. After all, the Bible quotes God speaking in Hebrew when He says, “Let there be light” and “Let us make man.” (If He had been speaking Aramaic, the Bible surely would not have hesitated to quote His original words—there is plenty of Aramaic in other parts of the Bible.) To whom was He speaking when He said these words? Certainly not to the Israelites or any other people—no people had been created yet! Hebrew must thus be the primordial language, the language of God and the angels, and God must have taught this language to the first humans.4 By the same logic, when the Bible says of Eve, “This one shall be called ‘woman’ [’ishah], since from a man [’ish] was she taken” (Gen. 2:23), this too seemed clear proof that the original language was Hebrew, since the words for “man” and “woman” were quite different in Aramaic, Akkadian, and other ancient languages. For such reasons Hebrew came to be known as “the holy tongue,”5 and well into modern times most people believed that all other languages—Greek, Latin, German, and so forth—were corruptions of that original, universal speech, just as the Bible recounted.

This hypothesis has been largely rejected by modern scholars, and the ramifications of its rejection go well beyond the Tower of Babel narrative itself.

Scholars still do not have an absolutely clear picture of the actual origins and complex interrelationship of the various Semitic languages, but most hypothesize that all Semitic languages do indeed go back to an original ancestor. It was not Hebrew, however. Linguists call this grandfather tongue “Proto-Semitic.” Proto-Semitic is still a theoretical entity; no actual text has ever been found to be written in it. But scholars do have a pretty good idea of what it must have looked like, and biblical Hebrew is quite a few developmental and chronological jumps away from it. Consider, for example, Hebrew’s repertoire of significant sounds—its phonemes—which are the basic building blocks of any language. (Technically, a phoneme is defined as “the smallest unit of sound capable of distinguishing between two words in a given language.”6 A phoneme is quite different from a letter, which is merely a conventional sign used in writing.) As time goes on, languages sometimes lose phonemes or gain new ones: English used to have a phoneme kh, like the final sound of loch in Scotland, and it was indeed pronounced kh in words like “laugh” or “night”; now that sound has, in some cases, merged with f, while in others it has disappeared entirely. Hebrew, too, seems to have lost some of the phonemes that existed in Proto-Semitic. Thus, Proto-Semitic used to have two separate phonemes, corresponding to English sh and th (as in “thing”), which merged into sh in Hebrew.7 Proto-Semitic had separate z and ð sounds (the latter corresponding to th in “this”), which merged into z in Hebrew; another three, originally distinct, phonemes of Proto-Semitic, represented by linguists as ![]() and

and ![]() , all merged into

, all merged into ![]() in biblical Hebrew (the same phoneme is realized as ts in modern Hebrew); and so forth. Vowels also changed: the “Canaanite shift” turned the formerly long

in biblical Hebrew (the same phoneme is realized as ts in modern Hebrew); and so forth. Vowels also changed: the “Canaanite shift” turned the formerly long ![]() sound into

sound into ![]() in Hebrew, hence Arabic sal

in Hebrew, hence Arabic sal![]() m versus Hebrew shal

m versus Hebrew shal![]() m. (Something similar happened in English, when, for example, the long

m. (Something similar happened in English, when, for example, the long ![]() of Old English st

of Old English st![]() n became

n became ![]() , as in “stone.”) In addition to such phonological shifts were many other changes—in morphology and grammar and syntax—and these too can be charted across the range of existing Semitic languages to situate Hebrew’s place among them and, hence, its path from Proto-Semitic.

, as in “stone.”) In addition to such phonological shifts were many other changes—in morphology and grammar and syntax—and these too can be charted across the range of existing Semitic languages to situate Hebrew’s place among them and, hence, its path from Proto-Semitic.

Quite apart from biblical Hebrew’s relationship to Proto-Semitic and other languages, linguists have also studied how Hebrew itself changed over time. All spoken languages change—and rather more quickly than most people imagine. Therefore, by carefully studying the linguistic features of different biblical texts (and, sometimes, comparing these to Hebrew inscriptions found by archaeologists, as well as using data from other Semitic languages), scholars have been able to piece together a detailed picture of how biblical Hebrew evolved over a period of some centuries. At a very early stage, for example, Hebrew seems to have had grammatical case endings, like Latin, German, Russian, and other languages; but these for the most part died out, as they did in English too. Words themselves change: old words drop out of a language and new ones appear, and often a particular word will change its meaning, slightly or radically as the case may be. Linguists can track such changes and sometimes use them to situate a particular biblical text chronologically vis-à-vis other texts.8 Finally, linguists have also distinguished different dialects of Hebrew in the Bible: the northern, or “Israelian,” dialect is actually markedly different from the idiom of Jerusalem.9

All this has had great ramifications for the study of the Bible as a whole. Tradition may assign the Pentateuch to Moses, the whole book of Isaiah to the eighth-century prophet by that name, and so forth, but the linguistic evidence is simply not consistent with those traditions. Moses, linguists say, cannot have written the Pentateuch, at least not in the form in which we know it—virtually all of its Hebrew is later than that which putatively existed in the time of Moses. Nor, if they are right, can the Pentateuch, or the book of Isaiah, or Psalms, or almost any other biblical book be the work of a single author: the language of all these books apparently represents the Hebrew of at least two different periods and/or geographic areas.

And so in several ways, the Tower of Babel narrative confronts us with a now-familiar discordance. For centuries and centuries, this tale was read as a parable of human hubris and divine retribution: long ago, people had sought to overstep their bounds, and God quickly put them back in their place. This was, quite simply, what the story meant—and if its lesson was an obvious one, it was nonetheless worth taking to heart, as it is even (especially?) today. Such is not, however, the story’s message for the modern scholar. Instead, this tale appears to be a deliberate jab at sophisticated Babylonian society, and along with that, an etiological explanation of the similarity-yet-distinctness of the Semitic languages. If, behind this etiology lies the belief that all Semitic languages were originally one, this belief could actually be historically accurate—but Proto-Semitic, not Hebrew, was the region’s first language.