Joseph and His Brothers

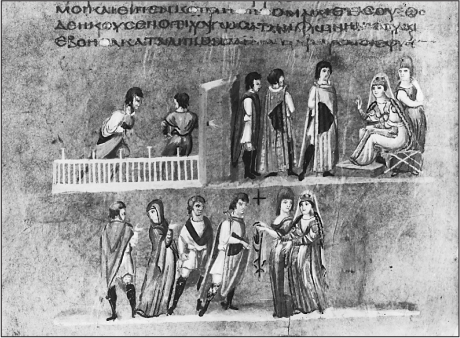

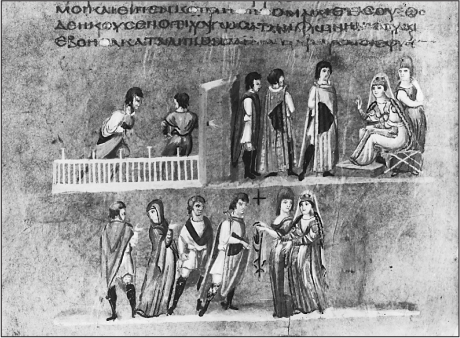

Potiphar and Wife from the Vienna Genesis (sixth century).

POTIPHAR’S WIFE. AN INDEPENDENT STORY. JOSEPH AND WISDOM. THE HYKSOS. JOSEPH’S DOUBLE PORTION. JACOB BLESSES HIS SONS.

Jacob loved Joseph more than any of his other children. Joseph ended up paying dearly for his father’s affection, although he eventually rose from the position of household slave to second in command of all of Egypt.

The narratives of Genesis examined thus far have been relatively short and relatively straightforward. The whole episode of the binding of Isaac occupies nineteen biblical verses; Jacob’s fight with the angel takes ten. The events of Joseph’s life, by contrast, stretch out over nine whole chapters and take up more than three hundred verses. His story is a complicated series of interrelated events. Here, in brief, is what happens.

After Simeon and Levi had destroyed the city of Shechem, Jacob and his family moved on to settle in Hebron, where Isaac and Abraham had lived. Among Jacob’s sons was Joseph, and he was the one whom Jacob loved the most. Understandably, this made Joseph’s brothers jealous. When Joseph dreamt that he would someday rule over his brothers and they would bow down to him, their jealousy only increased. One day, Jacob sent Joseph to check on his brothers and their sheep, and when he reached them they took hold of him and threw him into a nearby pit. At first they wanted to kill him, but the oldest of the brothers, Reuben, intervened to save him. When another brother, Judah, spotted an approaching caravan, he convinced his siblings to sell Joseph as a slave instead. They then took Joseph’s special garment—a gift from Jacob—and dipped it in blood, leading their father to believe that Joseph had been killed by a wild animal.

Joseph was transported to Egypt and sold as a slave to Potiphar, a high Egyptian official. Joseph soon rose to the top of Potiphar’s household staff. But Potiphar’s wife was attracted to Joseph, and although he rebuffed her repeated advances, one day she nevertheless seized him and said, “Lie with me!” Joseph fled, and Potiphar’s wife, fearing that the matter would be discovered, told her husband that Joseph had tried to rape her. Joseph was thrown into prison. There he met two jailed Egyptian officials, and one day he correctly interpreted their dreams. In keeping with Joseph’s interpretation, the chief cupbearer was restored to his former post—but he forgot all about the clever young man in prison.

When, two years later, the Egyptian king himself had a troubling dream, the cupbearer remembered Joseph, and he was rushed from his cell to Pharaoh’s throne room. After hearing Pharaoh’s dream, Joseph explained its significance: Egypt would enjoy seven years of plenty, but these were to be followed by seven years of famine. To prepare for the lean years ahead, the king put Joseph in charge of storing up and distributing food. He was now a high official himself, second only to Pharaoh.

After famine hit the region, Joseph’s brothers went down to Egypt to buy grain. They were brought before Joseph and bowed down before him, just as he had dreamt. He, of course, recognized them at once, but because of his Egyptian clothes and speech, they did not recognize him. Joseph accused them of being spies. “Not at all,” they protested, “we are all brothers—in fact, we have one more brother, the youngest, whom we left in Canaan.” Nevertheless, Joseph had them thrown into prison. After a short while he released all except Simeon; he would stay, Joseph said, until they brought this youngest brother, Benjamin, to Joseph to see.

Back in Canaan, Jacob was reluctant to release Benjamin to his sons’ care, but with food running out, he had no choice. The brothers returned to Egypt with Benjamin. Joseph greeted them warmly but conspired to hide his precious goblet in Benjamin’s grain sack before they left. On their way back to Canaan, the brothers were apprehended and the goblet was found in Benjamin’s sack; Benjamin was charged with the theft. Judah, fearing that the news would kill their father, offered to go to prison in Benjamin’s stead. At that point, Joseph could no longer restrain himself but burst into tears. “I am Joseph,” he said to his startled brothers, “the one you sold as a slave.”

Joseph made peace with his brothers and sent for his father to join him in Egypt. As a high official, Joseph was able to arrange for his father and brothers to settle in the rich area of Goshen. There Jacob lived in comfort and eventually died. His descendants stayed in the land of Goshen, where they grew to a mighty people.

Potiphar’s Wife

The story of Joseph left little for ancient interpreters to explain or justify. Though lengthy, the biblical narrative presented none of the apparent difficulties that elements in the stories of Abraham or Jacob or Rachel had: Joseph seemed altogether good, sagacious, and moderate in his behavior. He put his trust in God, and everything worked out well in the end. Interpreters noted that, although Joseph had ample opportunity to take revenge on his brothers for their cruelty—all those years of slavery and imprisonment were their doing, after all—he did not. If he did throw a scare into them for a while, even that had a purpose. Joseph manipulated events, interpreters said, so that Judah—the same brother who had looked on unfeelingly as Joseph was sold into slavery—found himself potentially in the same position once again. This was the moment when Benjamin, Joseph’s younger brother, was accused of theft and about to be jailed. But this time Judah did not stand idly by: he volunteered himself in Benjamin’s place. For Joseph, this was proof positive that at least one brother had learned his lesson, and Joseph burst into tears.1

There was, however, one part of Joseph’s story that particularly attracted the attention of ancient interpreters. As mentioned, the wife of Joseph’s Egyptian master, Potiphar, at one point tried to seduce him. This was a relatively minor episode, occupying only a few verses (Gen. 39:6–20); it was important in the narrative principally because it was what landed Joseph in prison, where he then went on to meet the Egyptian cupbearer who would eventually bring him to Pharaoh’s attention. Minor or not, however, the incident with Potiphar’s wife seemed to hold a special importance for ancient interpreters:

Now Joseph was handsome and good-looking. After these things, his master’s wife cast her eyes on Joseph and said, “Lie with me.” But he refused and said to his master’s wife, “Look, having me, my master has no concern about anything in the house, since he has put me in charge of everything that he has. There is no one greater in this house than I am, nor has he kept back anything from me except yourself, because you are his wife. How then could I do this great wickedness, and sin against God?” And although she spoke to Joseph day after day, he would not consent to lie with her or be with her. On a certain day, however, when he went into the house to do his work, none of the members of the household was in the house. She caught him by his garment, saying, “Lie with me!” But he left his garment in her hand, and fled and ran outside. When she saw that he had left his garment in her hand and had fled outside, she called out to the members of her household and said to them, “See, this Hebrew man has been brought to us to ‘sport’ with us! He came in to lie with me, but I cried out with a loud voice; and when he heard me raise my voice and cry out, he left his garment beside me, and fled outside.”

What was most significant to ancient interpreters was not this incident’s role in the overall narrative, but Joseph’s steadfast refusal to give in to the woman’s solicitations. The reason was simple. Scarcely anyone else in the Hebrew Bible is ever confronted with sexual temptation. Adultery, of course, was forbidden, but steamy scenes between men and women were simply not a normal part of biblical narrative. The only biblical figure to be confronted by temptation besides Joseph was Samson, and he failed miserably; beautiful women repeatedly led him into sin (Judges 14–16). Interpreters were therefore curious to understand the reason for Joseph’s stalwart resistance. Many seemed to chalk it up to his unusual character—indeed, in celebrating his virtue, they tended to exaggerate somewhat:

And she pleaded with him for one year and [then] a second one, but he refused to listen to her. She embraced him and held on to him in the house in order to compel him to lie with her, and closed the doors of the house and held on to him; but he left his garment in her hands and broke the door and ran away from her to the outside.

Jubilees 39:8–9

[Joseph recalled:] How often did the Egyptian woman threaten me with death! How often did she give me over to punishment, and then call me back and threaten me, and when I was unwilling to lie with her, she said to me: You will be my master, and [master] of everything that is in my house, if you will give yourself to me.

[Even after I was imprisoned,] she often sent to me saying: Consent to fulfill my desire and I will release you from the bonds and deliver you from the darkness. But not even in thought did I ever incline to her . . . When I was in her house, she used to bare her arms and breasts and legs, that I might go with her, and she was very beautiful, splendidly adorned to beguile me. But the Lord guarded me from her attempts.

Testament of Joseph 3:1–3; 9:1–2, 5

This was not true of all ancient interpreters, however. A close reading of the biblical text led some to believe that Joseph actually had been sorely tempted—it was only at the last minute that he changed his mind:

“On a certain day, however, when he went into the house to do his work . . .” [Gen. 39:11]: R. Yo![]() anan said: This [verse] teaches that the two of them [Joseph and Potiphar’s wife] had planned to sin together. “He went into the house to do his work”: Rab and Samuel [had disagreed on this phrase]: one said it really means to do his work, the other said it [is a euphemism that] means “to satisfy his desires.” He entered; [and then it says] “and none of the members of the household was in the house.” But is it at all possible that no one else was present in the large house of this wicked man [Potiphar]? It was taught in the school of R. Ishmael: that particular day was a festival of theirs, and everyone else had gone to their idolatrous rites, but she told them that she was sick. She had said [to herself] that there was no day in which she might indulge herself with Joseph “like this day.” [The biblical text continues:] “And she caught him by his garment . . .” At that moment the image of his father entered and appeared to him in the window.2

anan said: This [verse] teaches that the two of them [Joseph and Potiphar’s wife] had planned to sin together. “He went into the house to do his work”: Rab and Samuel [had disagreed on this phrase]: one said it really means to do his work, the other said it [is a euphemism that] means “to satisfy his desires.” He entered; [and then it says] “and none of the members of the household was in the house.” But is it at all possible that no one else was present in the large house of this wicked man [Potiphar]? It was taught in the school of R. Ishmael: that particular day was a festival of theirs, and everyone else had gone to their idolatrous rites, but she told them that she was sick. She had said [to herself] that there was no day in which she might indulge herself with Joseph “like this day.” [The biblical text continues:] “And she caught him by his garment . . .” At that moment the image of his father entered and appeared to him in the window.2

b. Talmud, Sota 36b

In this reading of the story, Joseph is not so innocent after all. If no one was in the house that day, the interpreter reasons, it must have been some kind of holiday or festival, and everyone else had gone to the celebration. If, nevertheless, Potiphar’s wife was at home that day, she probably had made up some excuse, telling people she was not feeling well; she was certainly up to no good. But what of Joseph? He is said to go to the house “to do his work,” a somewhat ambiguous phrase at best.3 Surely he ought, under the circumstances, to have anticipated that she might be staying behind in the big, empty house; if he nevertheless showed up at work as usual, did this not indicate that he was, at the very least, of two minds about the woman’s oft-repeated indecent proposal? Indeed, it seemed possible that he knew exactly what was going to happen and had even arranged the whole thing with her. It was only at the last minute, when his father’s image4 appeared to him miraculously in the window, that Joseph changed his mind.

If the biblical narrative is interpreted in this fashion, Joseph acquires a somewhat more human face. If, after all, Joseph had not been the slightest bit interested in his master’s wife (as the other interpreters above and, indeed, the biblical text itself had maintained), well, perhaps that indicated that she was not so beguiling after all—or that Joseph was some sort of superhuman, unmoved by the desires to which all flesh is heir. Who could emulate such a model? But if, to the contrary, Joseph had indeed been tempted but, aided by his father’s miraculous appearance (or, in an alternate scenario, by a sudden attack of memory that brought back his “father’s teachings”),5 he had fled the lady’s beguilement, then he offered a ready lesson for later readers. Even the greatest heroes, the story now suggested, are sometimes tempted to sin; their greatness lies precisely in their ability to overcome that temptation. (As Katharine Hepburn says to Humphrey Bogart in The African Queen, “Nature, Mr. Allnut, is what we are put in this world to rise above.”)

Too Good a Story

Modern interpreters have of course been struck by the contrast between the story of Joseph and those of other figures in Genesis. Here, they point out, is no schematic narrative at all, but a full-fledged tale of adventure, with a plot that twists and turns and keeps the reader riveted until the climactic scene, when Joseph reveals his true identity to his brothers. (Rightly did the Qur’an, in retelling the biblical tale, call it “the most beautiful of stories.”) But for modern scholars, that is just the trouble; the story of Joseph reads more like a work of fiction than anything having to do with history.6 They suspect that behind it may stand an altogether invented tale—Egyptian, or perhaps Canaanite—that had enjoyed great popularity on its own before someone came along and changed the main characters to Jacob and his twelve sons.7

According to this approach, the original story would have told of a family of brothers—not necessarily twelve, but at least four or five—in which the youngest, because he was the youngest, was cherished and spoiled by their father. Of all the brothers, the least jealous in such a situation would likely be the oldest: he had, after all, his own privileged status, and he was also the furthest in age from the youngest and thus less prone to rivalry with him than the others. So it was the oldest who intervened to try to save his sibling when his other brothers threatened him. Nevertheless, the youngest was sold by these other brothers as a slave; then, through his cleverness as a dream interpreter, he ended up as the king’s right-hand man. In this role he reencountered his brothers, who now failed to recognize him. There ensued all the back-and-forth maneuvering of the present story, since the youngest brother demanded that Brother X (perhaps his full brother and no half-brother, like the others) be brought before him as well, along with his mother and father. When this was finally done, the youngest revealed his true identity (or, possibly, Brother X recognized him). A tearful reunion ensued.

Scholars have pointed to various details in the biblical narrative of Joseph that indicate that it was indeed adapted from such a narrative. To begin with, Joseph is described in the Bible as if he were Jacob’s youngest son: “Now Israel [= Jacob] loved Joseph more than any of his other children, because he was the son of his old age” (Gen. 37:3). But of course Joseph is not Jacob’s youngest son; he certainly had been the youngest at some point, but even before the start of this story, Benjamin was born (Gen. 35:18). So why does it say “more than any of his other children”? Surely if being a “son of his old age” was the determining factor, Jacob ought to have loved Benjamin at least as much, or more.8 Then there is the prophetic dream that Joseph has, in which “the sun, the moon, and eleven stars were bowing down to me” (Gen. 37:9). Clearly this refers to Joseph’s father, mother, and eleven brothers. That is why Jacob, upon hearing the dream, asks Joseph, “Shall we indeed come, I and your mother and your brothers, and bow to the ground before you?” (Gen. 37:10). But in the book of Genesis, by the time Joseph has this dream, his mother, Rachel, has already died (Gen. 35:19). The adaptor may have adjusted the number of stars in the dream to fit the exact number of Joseph’s brothers (including Benjamin), but interpreters suspect he forgot to omit the moon from the dream in his adaptation.

Finally, there is the role of the oldest son in the biblical story, Reuben. For the reasons already mentioned, he ought to be the brother who was not jealous and, hence, the hero—and that is indeed how Reuben starts out, boldly intervening to save Joseph (Gen. 37:21–22). He also speaks up later on, reproving his brothers for what they did (Gen. 42:22) and still later offering his own two sons as guarantors for Benjamin’s safety (Gen. 42:37). So far, he is the only “good” brother besides Joseph. But at this point suddenly another brother, Judah, emerges. Now it is Judah who intervenes with Jacob to send Benjamin to Egypt, and unlike Reuben’s offer of a guarantee, Judah’s is accepted (Gen. 43:8–10). From this point on, Reuben disappears. It is “Judah and his brothers” who go to Joseph’s house (Gen. 44:14), not “Reuben and his brothers,” and it is Judah who acts as spokesman, as if he were indeed the oldest (Gen. 44:16). Judah is also the one who selflessly offers to take Benjamin’s place in prison (Gen. 44:33–34). Scholars suppose that, in the adaptation of the story, Reuben was at first mechanically put in the role of the “oldest”—he was, after all, Jacob’s oldest son. But whoever was doing the adapting knew full well that the tribe of Reuben had long ago virtually disappeared: his listeners would be principally descendants of the tribe of Judah—so Judah was, somewhat inconsistently, given the role of spokesman and hero at the end of the story.9

Joseph the Sage

Scholars noticed something else about the Joseph story. The story itself bears a particular “signature”; it seems to belong to the world of ancient Near Eastern wisdom literature.10 As will be seen presently, wisdom was indeed a world; all over the ancient Near East were sages who pursued wisdom, and their writings have survived in Egyptian, Sumerian, Akkadian, Aramaic, and other ancient languages. One of the specialties of the ancient Near Eastern sage was advising the king—just as Joseph ends up doing. Indeed, sages were prominent in court as interpreters of dreams and other signs—just like Joseph. They also had a particular ideology, the “wisdom ideology”: they maintained that underlying all of reality is a detailed, divinely established plan, so that everything that happens in this world unfolds in accordance with a preestablished pattern. This belief is precisely reflected in what Joseph says to his brothers (twice, in fact) as a kind of moral of the story: “Do not be distressed or angry with yourselves because you sold me here; for it was [really] God who sent me here ahead of you in order to keep [people] alive . . . You planned to do me harm, but God had planned it for the good” (Gen. 44:5; 50:20).

In short, to modern scholars, Joseph looks like the very model of the ancient Near Eastern sage. Indeed, he is the only one of Israel’s ancestors who is called “wise” (Gen. 41:39—this is the same word as the noun “sage” in Hebrew), and throughout his whole story of ups and downs—first he is sold as a slave, then he rises to the top of Potiphar’s staff, then back down to the darkest dungeon, then back up to Pharaoh’s court and his ultimate vindication and triumph—Joseph reveals that cardinal sagely virtue of patience. An ancient Near Eastern sage was patient precisely because he believed that everything in this world happens according to the divine plan; things will always, therefore, turn out for the best, no matter how bad they may appear now. To scholars, the Joseph story thus looks like an altogether didactic tale designed not only to capture people’s attention but to encapsulate, and inculcate, the basic ideology of wisdom. Such a story, they believe, may have circulated independently for a time, but it was eventually fitted to the circumstances of Jacob’s family as a way of accounting for the fact that the Israelites ended up migrating en masse to Egypt and coming to be (as they are in the next biblical book, Exodus) enslaved to the Egyptian king.

The Hyksos

But if the Joseph story was, according to this line of argument, originally a work of fiction, it nonetheless intersected with a bit of historical reality. Ancient Egyptian records reveal that Semitic peoples from the area of Canaan did indeed frequently go down to Egypt in time of famine (as Abram and Sarai are reported to have done in Genesis 12). Egypt, after all, did not depend on the altogether undependable rainfall in Canaan to water its crops: it had the Nile, whose annual overflow made it the ideal source of irrigation. So, when there was a shortage of food in their own land, Canaanites could always make their way southward—they were probably not a strange sight to Egyptians.

Indeed, Egyptian records report on a period when some Western Semites, known as the Hyksos, actually took over control of Egypt for a century or so (approximately 1670–1570 BCE). These foreigners (Hyksos is actually the Greek form of an ancient Egyptian phrase meaning “rulers of foreign lands”) appear to have gained control of a large area of Egypt and established their capital at Avaris, in the Nile delta; their rule extended to Memphis, Hermopolis, and other cities.11 It would be tempting to identify Joseph and his family as part of this non-Egyptian, Western Semitic population, but that would require a leap of the imagination (and, probably, chronology); most scholars find it more prudent to suppose that the historical memory of such a period of Semitic rule in Egypt helped to shape either the original tale described above or its application in the Bible to Joseph and his brothers. In any case, the Hyksos were eventually expelled from Egypt, and many scholars believe that this historical circumstance may likewise have some relation to the Bible, namely, to the story of the mass exodus from Egypt under the leadership of Moses. (Again, while a straightforward identification of the two poses chronological and other difficulties, the role of these events in shaping historical memory can scarcely be discounted.) One thing is clear: a record of the period of Hyksos rule survived in Egypt long after the events themselves. A “reasonably accurate portrayal” of the Hyksos period was written up in Demotic script about a thousand years after the events,12 and the memory of Hyksos rule is reflected even later in Greek and other writings. The events of the Joseph story, too, may reflect some memory of this historical reality.

Who, according to modern scholars, might be responsible for the adaptation of an originally fictional tale to Jacob and his family? On this subject there is scarcely any unity among modern scholars: some have tried to divide the story up among the traditional sources J and E, but with widely varying results. Estimates of the date of its composition also differ greatly from one another. There may be something of a clue to the biblical story’s origin in the heroic role that Joseph plays. Joseph was, after all, the reputed ancestor of the two great northern tribes, Ephraim and Manasseh. The depiction of Joseph as the hero of the story, the one before whom his brothers bow, may thus betray an originally northern provenance for the story. (As we shall see, there are other reasons for associating the idea of an Israelite presence in Egypt specifically with these northern tribes.) If so, at some point the narrative must have made its way southward, to the Kingdom of Judah. The fact that Judah upstages Reuben as the de facto older brother can hardly be coincidental: this substitution argues the presence of a Judahite hand in the story’s final version.

Joseph’s Double Portion

After Joseph has revealed his true identity and settled his father and brothers in Egypt, the Bible reports an odd happening:

After this Joseph was told, “Your father is ill.” So he took with him his two sons, Manasseh and Ephraim. When Jacob was informed, “Your son Joseph has come to you,” Israel [Jacob’s other name] summoned his strength and sat up in bed. Then Jacob said to Joseph, “God Almighty appeared to me at Luz, in the land of Canaan, and He blessed me; He said to me, ‘I will make you fruitful and increase your numbers. I will make of you a mass of peoples, and I will give this land to your offspring after you as a perpetual holding.’ Now, those two sons of yours who were born to you in the land of Egypt before I came to you in Egypt—they are hereby mine. Ephraim and Manasseh will be mine, just as Reuben and Simeon are. But any children born to you after them will be yours; they will be recorded as heirs of their brothers [Ephraim and Manasseh] with regard to their inheritance.”

What the aged Jacob does here is legally adopt Joseph’s sons Ephraim and Manasseh as his own. Henceforth they will be considered coequal heirs with Jacob’s other sons, Reuben, Simeon, Levi, and so forth. Thus, while Joseph formerly had one-twelfth of the inheritance coming to him, his single share will now be replaced by two shares, those of Ephraim and Manasseh. In effect, Joseph gets a double portion. (Any future sons of Joseph will, of course, be legally his own; at the same time, they will presumably have to be considered as sons of either Ephraim or Manasseh for purposes of inheritance.)

Modern scholars see behind this incident a midcourse correction in Israel’s list of tribes. The idea that there were precisely twelve tribes seems to have become, at an early stage, a fixity; it could not be changed.13 But, as we shall see presently, reality changed. At one point Levi was apparently a tribe like any other, and it may well have had its own tribal land. Later, however, this tribe became essentially landless; the Levites became a scattered people of priests and other religious functionaries, with only a few cities to call their own. Simeon, too, appears to have disappeared. So what was to become of the number twelve? To compensate for at least one of these absences, the territory elsewhere attributed to a single ancestor figure, Joseph—a territory that included the lands called “Ephraim” and “Manasseh”—was counted as two territories, each with its own ancestor figure. Joseph was said to have had two sons by those names, each of whom was a tribal founder on his own.14 In that way, a tribal list could omit the Levites (like the list in Num. 26:1–51) or the Simeonites (as in Deuteronomy 33) and, by replacing “Joseph” with “Ephraim and Manasseh,” still include the names of twelve tribes.

After adopting Ephraim and Manasseh, Jacob then asks to bless his two new sons—and here is another kind of midcourse correction:

Joseph took them both, Ephraim in his right hand toward Israel’s left, and Manasseh in his left hand toward Israel’s right, and brought them near him. But Israel stretched out his right hand and laid it on the head of Ephraim, who was the younger, and his left hand on the head of Manasseh, crossing his hands, for Manasseh was the firstborn . . . When Joseph saw that his father laid his right hand on the head of Ephraim, it displeased him; so he took his father’s hand, to remove it from Ephraim’s head to Manasseh’s head. Joseph said to his father, “Not so, my father! This one is the firstborn, put your right hand on his head.” But his father refused, and said, “I know, my son, I know; he also will become a people, and he also will be great. Nevertheless his younger brother will be greater than he, and his offspring will become a multitude of nations.”

Apparently—as in the case of Jacob and Esau—this patriarchal blessing portends the future dominance of the originally less powerful people. Perhaps indeed the land of Manasseh originally dominated Ephraim; in any case, we know that an Ephraimite, Jeroboam, eventually took control of the whole population of the north (1 Kings 11:26; 12:1–14:20), including Manasseh. That, modern scholars say, is really what is being enacted by Jacob’s promotion of Ephraim to the status of firstborn.

To ancient interpreters, this whole incident was reminiscent of similar cases of the younger son displacing the older—Isaac supplanting Ishmael, and Jacob Esau. For some early Christians, however, the phrase “crossing his hands” seemed to hold added significance. They saw in it a reference to the cross itself, and thus to the ultimate triumph of their faith:

And he [Joseph] brought Ephraim and Manasseh, intending that Manasseh, because he was the older, should be blessed, for he brought him to the right hand of his father Jacob. But Jacob saw in the Spirit [that is, prophetically] a symbol of the people to come [namely, Christianity]. For what does it say? “And Jacob crossed his hands . . .” Observe how, by these means, he has ordained this people [the Christians] should be first, and heir of the covenant.

Letter of Barnabas 13:4–6

Jacob Blesses the Tribes

After these events, when Jacob knew he was soon to die, he summoned all his sons to his bedside to receive his final blessing. This certainly seemed a significant moment: by a common understanding, people who were on the brink of death already had one foot in the next world. Their last words were thus likely to contain extraordinary insight—and perhaps some clues as to what was to happen in times to come. (This is in fact stated explicitly in the present instance: in summoning his sons, Jacob says, “Gather around that I may tell you what will happen to you in days to come” [Gen. 49:1].)

Jacob starts off, however, by talking about the past. In blessing his first son, Reuben, he evokes the shameful incident of Reuben’s sleeping with Jacob’s concubine Bilhah (Gen. 35:21–22):

Reuben, you are my firstborn, my strength and the first fruits of my vigor, privileged in rank and in power.

But wanton as water, you’ll have privilege no more,

For you went to your father’s bed—and then defiled it. He went to my bed!

The general sense of this text is clear enough: Reuben, as Jacob’s firstborn, should have been entitled to the firstborn’s special birthright (the same birthright that Esau sold to Jacob for some lentil stew). But because Reuben sinned with Bilhah, “you’ll have privilege no more,” Jacob says—in other words, I am awarding your birthright’s double portion to Joseph (as explained above).

If such is the general sense, however, interpreters were troubled by one phrase in Jacob’s words: he says Reuben was “wanton as water.” How can water be wanton? Water is just water. It has no character traits, and if it plays any role in human life, that role is undoubtedly a positive one: without water, we cannot survive. (Modern scholars are thus still puzzled by this phrase of Jacob’s.)

Faced with this problem, some ancient interpreters proposed that Jacob was referring to something connected to the circumstances of Reuben’s sin with Bilhah: perhaps what he was saying was that Reuben had been wanton with or in water. Eventually—thinking of a similar incident in the biblical story of David and Bathsheba—interpreters suggested that what Jacob meant was that Reuben had seen Bilhah bathing in water, and it was the sight of her nakedness there that led him into the subsequent wantonness:

For, had I not seen Bilhah bathing in a covered place, I would never have fallen into this great iniquity. But my mind, clinging to the thought of the woman’s nakedness, would not allow me to sleep until I had done the abomination.

Testament of Reuben 3:11–1515

At the same time, Bilhah had not intended that Reuben see her: she was bathing “in a covered place.”

Jacob’s words to Reuben in Gen. 49:3–4 seemed to contain other clues as to the precise circumstances of Reuben’s sin: “For you went to your father’s bed,” Jacob said. For ancient interpreters, this phrase16 suggested that Bilhah was actually a passive participant in the whole affair. After all, Jacob did not speak of Reuben and Bilhah having arranged some tryst somewhere, nor even that they both entered the bed at the same time—otherwise, the text would have said, “For you and Bilhah went to your father’s bed.” Indeed, the very fact that it was Reuben’s “father’s bed” must have meant that Jacob was away at the time (otherwise, how could this all take place in his bed?). Interpreters therefore theorized that, in Jacob’s absence, Bilhah had gone to bed alone; at some later point, Reuben “went to your father’s bed” to commit his transgression when Bilhah was already asleep. She was thus altogether innocent.

In considering the full meaning of Jacob’s words to Reuben, ancient interpreters naturally compared those words with the narrative account of this same incident that appears somewhat earlier in Genesis. Even there, the details are sparse; in fact, the episode is related in just a few words within the surrounding passage:

Israel [that is, Jacob] traveled on, and pitched his tent beyond Migdal-Eder. Now, at the time when Israel was living in that land, Reuben went and lay with Bilhah his father’s concubine; and Israel heard of it.

Now, the sons of Jacob were twelve. The sons of Leah: Reuben, Jacob’s firstborn, and Simeon, Levi, Judah, Issachar [and so forth].

Even these few words, however, raised questions for ancient interpreters. Particularly puzzling was the closing assertion, “and Israel heard of it.” This seemed terribly anticlimactic. Jacob heard about it? Surely something ought to have been said about what happened as a result of his hearing of it—that Jacob banished Reuben then and there, or that he punched him in the nose, or at least that he resolved to disinherit him later on. (Indeed, the translators of the Septuagint felt so strongly that something was missing that they added the phrase “and he became very angry” after “and Israel heard of it.”)

Other interpreters, however, came up with another solution. They connected the anticlimactic mention of Jacob’s hearing about it to what comes in the next sentence: “Now, the sons of Jacob were twelve . . .” At first this could not have looked like a very promising tack; was not this just another one of those tedious biblical genealogies? But on reflection, perhaps it could indeed be related to the Reuben-Bilhah incident. After Jacob heard of it, he said, “That’s it! No more wives and concubines for me—they only bring trouble.” In other words: “And Israel heard of it, [and as a result,] the sons of Jacob were twelve” and no more.

And Jacob was exceedingly angry with Reuben because he had lain with Bilhah . . . And Jacob did not approach her again because Reuben had defiled her.

Jubilees 33:9

And immediately an angel of God revealed to my father Jacob concerning my impiety, and when he came he mourned over me, and he touched her no more.

Testament of Reuben 3:15

In short, from Jacob’s blessing and the related narrative in Genesis 35, ancient interpreters were able to reconstruct a good deal of the circumstances of Reuben’s sin. It all came about by accident, when Reuben saw Bilhah bathing in a covered place. Jacob was away at the time, so that night, after Bilhah had gone to bed alone, Reuben slipped into her room and committed his sin. Bilhah herself was quite innocent, but Jacob nonetheless refrained from further relations with her thereafter: there were to be only twelve sons of Jacob. As for Reuben, he was punished by losing the precious birthright.

The Scepter Will Not Depart

When Judah’s turn comes to be blessed, Jacob waxes more positive:

Judah are you, let your brothers praise32 you.

Your hand’s on your enemies’ neck, and even your brothers bow before you.

Judah is like a lion’s cub—you arose, my son, from ravaging.

Crouching and stalking like a lion, like the king of beasts17 none dare challenge.

Here, Jacob apparently praises Judah’s physical strength and prowess in war. Although the Bible did not relate any specific instances of these, ancient interpreters assumed they must have taken place;18 they thus understood Jacob’s words as providing the justification for the next part of the blessing, in which Jacob predicts the future prominence of the tribe of Judah’s descendants. In other words: Judah, since you have shown yourself to be so strong and brave that nowadays “even your brothers bow before you,” it is only appropriate that in the future your tribe will be the one to dominate the others:

The scepter shall not depart from Judah, nor the staff from between his feet,

Until he enters Shiloh—to him will nations pay homage.

The scepter and staff (symbols of kingly power) will never be transferred from the tribe of Judah to another; on the contrary, even foreign nations will pay Judah homage. And indeed, King David, Israel’s greatest king, did come from the tribe of Judah.

For ancient interpreters, however, these very words seemed highly problematic. “The scepter shall not depart from Judah” means, quite unambiguously, that a Judahite king will rule over Israel forever. But that was not to be. After the heyday of David’s reign and that of his son Solomon, the great empire that they had established split into two. David’s grandson Rehoboam remained in power only in the southern part, the Kingdom of Judah, while the northern part, called the Kingdom of Israel, was taken over by an Ephraimite ruler. Then, in the sixth century, Davidic rule ceased even in the southern kingdom: Judah was conquered by the Babylonians, and thereby began a succession of foreign rulers, first Babylonians, then Medes and Persians, Greeks, Hellenized Egyptians, Hellenized Syrians, and Romans. Jacob’s prediction, “The scepter shall not depart from Judah,” must have appeared to later Jews as having fallen flat on its face.

Unless . . . Unless “the scepter shall not depart from Judah” did not really mean that a king from Judah would always rule over Israel. In the light of later events, interpreters reasoned, it couldn’t have meant that. The scepter did depart. Perhaps, then, the meaning was that, although the scepter was to depart at some point, this condition was not final: what Jacob had meant was that the scepter will not depart forever. At some point, the tribe of Judah was to regain the kingship and then it would not only rule over Israel but foreign nations as well: “to him will nations pay homage.”

Such thoughts in turn led interpreters to take a closer look at the beginning of the second line, “Until he enters Shiloh.” Whatever else these words mean—as we shall see, they are somewhat difficult—the word “until” seemed to work well with the interpretation just given. What Jacob was saying was that, although the scepter would indeed depart from Judah for a time—the empire would split, then the Babylonians would invade, and so forth—that sorry state of affairs would last only until something else happened. Then God would return things to what they had been; indeed, foreign nations would now again pay homage to the Jewish king as they once had.

One ancient interpreter thus had Jacob’s son Judah explain his father’s prediction in somewhat different form:

[Judah says:] The Lord will bring upon them factions, and there will be continuous wars in Israel, and my rule shall be ended by a foreign people, until the salvation of Israel comes, until the God of righteousness appears, so that Jacob may enjoy peace along with all the nations. [Then] He will guard the power of my kingdom forever. For with an oath the Lord swore to me that my kingship will not depart from my seed all the days, forever.

Testament of Judah 22:1–3

Biblical interpretation never takes place in a vacuum, and it is no coincidence that this particular understanding of Jacob’s words arose at a time when Jews dreamt as never before of the possible restoration of Israel to political independence and military might. Indeed, they did not simply yearn in general terms for an improvement in conditions; instead, their hopes focused on the possibility of a specific new king coming to power. He would restore Israel’s fortunes. Such a king was sometimes referred to by the Hebrew word mashia![]() , an elegant synonym for “king” that literally means “anointed one.” (This word came into Greek, and subsequently into English, as “messiah.”)

, an elegant synonym for “king” that literally means “anointed one.” (This word came into Greek, and subsequently into English, as “messiah.”)

As a consequence, some interpreters scrutinized Jacob’s words for a reference to such a king. In this search, attention fell once again on the mysterious word “Shiloh.” Now a slightly different reading was proposed (remember, vowels were often left unexpressed in the Hebrew writing system): shello, “pertaining to him” or “of him.” If the future king was not specifically mentioned, was it not possible that Jacob had alluded to him in suggesting that things would eventually change when that which belongs to him (the future king) arrives? Then, even foreign nations would pay Israel homage:

A ruler shall not be absent from Judah, nor a leader from his loins, until there come the things stored away for him; and he is the expectation of the nations.

Septuagint, Gen. 49:10

The ruler shall not depart from the house of Judah, nor the scribe from his children’s children forever; until the Messiah comes, to whom belongs the kingdom, and to him shall the peoples be obedient.

Targum Onqelos Gen. 49:10

And so, it turned out that, not only was Jacob’s prediction not wrong, it was actually a hint about the very thing that people were hoping for in the ancient interpreters’ own day. Jacob had subtly alluded to a time when a new king would arise in Israel and bring it back to the glory days of David and Solomon.

An Ancient Text

As usual, modern scholars have a somewhat different reading of these same texts. To begin with, it should be recalled that this whole section of blessings is considered by scholars to be among the oldest parts of the Bible. This conclusion is based in part on linguistic and stylistic considerations, but also on the content of the blessings. Take, for example, the “blessing” of Simeon and Levi already discussed in chapter 11:

Simeon and Levi are brothers; tools of violence are their stock-in-trade.

May I never enter into their company, nor take pleasure in their assembly.

For in their anger they would kill a man, and in a good mood, hamstring an ox!

Cursed be their anger, how fierce! Their wrath is harsh indeed.

I shall divide them in Jacob and scatter them in Israel.

Gen. 49:5–7

The last line “predicts” that the tribes of Simeon and Levi will be scattered among the other tribes. Even if this were written after the events, scholars theorize, the passage preserves a memory of the time when the Levites did indeed have their own land. Elsewhere, that memory is not preserved. It is simply axiomatic that the Levites are a priestly tribe and were never intended to have their own territory; “the LORD is their territory” (Deut. 10:9; 18:2). At the same time, there is nothing in Gen. 49:5–7 that even hints that its author had some awareness of the Levites’ future role as priests; apparently, that had not happened yet.

For modern scholars, Jacob’s “blessing” of Reuben provides another indication of the antiquity of this whole section. It also seems to have a quite different message from that seen earlier:

Reuben, you are my firstborn, my strength and the first fruits of my vigor, privileged in rank and in power.

But wanton as water, you’ll have privilege no more,

For you went to your father’s bed—and then defiled it. He went to my bed!

Gen. 49:3–4

What this passage implies for modern scholars is that although the tribe of Reuben had at first been Jacob’s “firstborn,” that is, it had been the most powerful and dominant tribe for a while, it subsequently lost this position and became a virtual nonentity. (The same conclusion, scholars say, is suggested by a number of passages elsewhere in the Bible.)19 If so, these words would seem to reflect a relatively early stage of Israelite history. The replacement of Reuben by Judah as the dominant tribe in the south probably took place roughly around the time of King David, that is, at the start of the tenth century BCE, if not earlier. Of course, this “blessing” may well have been written after that time, but not long after, since it still feels the need to account for Reuben’s demise. In fact, modern scholars say, that is what it is really talking about.

The reason it gives for the demise of the tribe of Reuben is one of the most stereotypical infractions in the ancient Near East: Reuben “went to [his] father’s bed,” a euphemism meaning he slept with his father’s wife. (It should be noted that, in a polygamous society, sleeping with one’s father’s wife was not necessarily sleeping with one’s own mother. More likely, the wife involved was the pretty young woman whom the father had recently acquired but who was actually closer, in age and perhaps in other ways, to the son.) This was not only a sexual infraction but a political one: he who slept with the king’s wife was considered to have made a de facto claim to the throne (see 2 Sam. 16:21; 1 Kings 2:13–25), and no doubt, even when an actual king was not involved, this act was considered one of arrogant supersession. Perhaps for this reason does the prohibition of sleeping with one’s father’s wife appear no fewer than four times in the Pentateuch (Lev. 18:7; 20:11; Deut. 23:1; 27:20). So Reuben is asserted to have committed this act of lèse-majesté. Did any such thing ever happen? Of course not, a modern scholar would say. This ancient text is simply invoking a stereotypical sin to explain why the tribe of Reuben lost its homeland and disappeared.

The Overall Purpose of Jacob’s Blessings

Taking a step backward, modern scholars surveying Jacob’s blessings see one overall purpose in them. After all, they present Jacob as blessing each of his sons, the ancestors of Israel’s twelve tribes; if so, and given the apparently early date of these blessings, their purpose appears to have been to put the official stamp, as it were, on their union. “Jacob had twelve sons,” the text is saying, “and so it is only appropriate that the twelve tribes descended from them should be one kingdom.” In political terms, this would again point to the time of David and Solomon, when such a union was first achieved. The blessing of Judah indicates an awareness that David, who came from Judah, would establish a royal dynasty. But nothing in that blessing or any of the others reveals any hint of the fact that the twelve tribes will split apart again soon after Solomon’s reign; on the contrary, “the scepter shall not depart from Judah.” Beyond these points, scholars also note that the blessings preserve the traditional order of the tribes (Reuben, Simeon, Levi, Judah, and so forth), an order that probably corresponds to an earlier ranking of size or power. But that ranking is now no longer valid: Judah is the big tribe of the south and the king’s home territory. That is why the blessings take the three tribes that traditionally came before Judah and, in attributing some plausible sin to their founders (sleeping with one’s father’s wife, being violent hotheads), “predict” their eventual displacement.

In attributing to Simeon and Levi unbridled anger and violence, their blessing may have accounted for the ultimate disappearance of these tribes; as we have seen, however, scholars also believe that it created a problem. Later Israelites, hearing or reading this passage, must have wondered: what violence? Nothing else in the Bible ever referred to these tribes as being violent. The question may have been pushed aside for a while, but eventually, as Scripture came to be thought of more and more as leaving no loose ends, some explanation seemed required. Out of this, scholars claim, came the insertion of the story of Dinah into the book of Genesis (see above, chapter 11).

By the same logic, this must also have occurred with Reuben’s sin, “you went to your father’s bed.” When did that happen, later readers wondered, and who was the woman? It was to answer this question, scholars say, that the same editor who inserted the Dinah story also stuck a single sentence into chapter 35 of Genesis, a sentence that likewise sought to provide some context for Jacob’s words:

Israel [that is, Jacob] traveled on, and pitched his tent beyond Migdal-Eder. Now, at the time when Israel was living in that land, Reuben went and lay with Bilhah his father’s concubine; and Israel heard of it.

Now, the sons of Jacob were twelve. The sons of Leah: Reuben, Jacob’s firstborn, and Simeon, Levi, Judah, Issachar [and so forth].

Gen. 35:21–23

The insertion, indicated in italics, really has nothing to do with what precedes it or follows it; that alone, for modern scholars, might suggest that it is an insertion. Moreover, what it says betrays the same gingerly, minimalist approach that this editor displayed in an insertion seen earlier (Gen. 30:21). Here again, he includes the absolute minimum of required information: when and where the incident took place, and who the “wife” in question was. To these bare facts he adds only the observation “and Israel [that is, Jacob] heard of it.” The reason for this is obvious: if Jacob is going to chew out his son for his crime in Gen. 49:3–5, he has to have heard about it from someone—and normally, the participants in an adulterous union are not eager to share that information with the woman’s husband. But Jacob must have found out about it somehow, so, rather than speculate as to how, the editor simply said, “and Israel heard of it.”

How often does it happen in the history of interpretation that an explanation designed to solve one problem in the Bible ends up creating another! So it turned out here as well. The assertion “and Israel heard of it” seemed terribly anticlimactic. It was this apparent anticlimax that produced the interpretive motif seen earlier (and others).20

As for the blessing of Judah, modern scholars’ understanding is likewise quite different from the ancient approach studied above.

Judah are you, let your brothers praise you.

Your hand’s on your enemies’ neck, and even your brothers bow before you.

Judah is like a lion’s cub—you arose, my son, from ravaging.

Crouching and stalking like a lion, like the king of beasts none dare challenge.

Gen. 49:8–9

Here, for modern scholars, is a rather realistic portrait of this tribe’s rise to power as epitomized in the career of King David (his tribe’s eponym, Judah, really stands for him here). It was indeed David’s abilities as a fighter—first as the leader of a small, vicious guerrilla band, and eventually as the commander of a regular army—that not only subdued Judah’s out-and-out enemies (“Your hand’s on your enemies’ neck”), but likewise caused the other tribes (“your brothers”) to submit to his authority. In putting these words in Jacob’s mouth, the Bible was, according to most scholars, “predicting” what had probably already taken place, though not long before. (Elsewhere, in the books of 1 and 2 Samuel, the Bible recounts in greater detail the sometimes ruthless steps by which David and the Judahites gained the throne, quite literally rising up by ravaging.)

But then Jacob turns to the future of the kingdom that David had established:

The scepter shall not depart from Judah, nor the staff from between his feet,

Until he enters Shiloh—to him will nations pay homage.

Gen. 49:10

Unlike the previous lines, these two are, in the view of modern scholars, an actual prediction of the future. Judah will always rule, this text is saying. That is the general sense, but it must be admitted that the second line cited has always been mysterious to scholars, and still is today. The main problem is the word “Shiloh.” Shiloh was an old city in the territory of Ephraim where the Ark of the LORD once rested. If so, the sense of the second line might be “until he [Judah] reaches Shiloh,” that is, until Davidic power extends into Ephraim (and, by extension, the whole north). But the same letters might also spell out Shelah, the name of one of the Judahite clans (see Gen. 38:5; Num. 26:20; 1 Chr. 2:3), perhaps one that was prominent when these lines were written. Along with these two possibilities, some modern scholars have maintained that the text has been corrupted in transmission, and that Shiloh/Shelah is really two words, shai lo, yielding “until a tribute is brought to him.” Whichever reading is preferred, one further lexical point requires clarification: the word “until” does not mean that the scepter shall not depart until such-and-such happens—that, scholars say, would make no sense. Instead, it really means “to such an extent that” (as this phrase does elsewhere in the Bible: Gen. 26:13; 41:49; 2 Sam. 23:10): in other words, Judah will solidify its hold on power, so much so that tribute will be brought to him (or Shelah will come, or he will enter Shiloh) and the fealty of foreign nations will be his.

In short: for modern scholars, Jacob’s blessings of his sons seem to go back to the time of David or Solomon. Although the tribe of Reuben had, in still earlier times, been dominant, his “blessing” demotes him to an inferior position. Simeon and Levi are likewise condemned to being scattered and dispersed, another vaticinium ex eventu, while Judah’s blessing really refers to David’s establishment of the royal dynasty, one that, as far as this passage is concerned, will last forever. History, however, was to tell a different tale.