Moses in Egypt

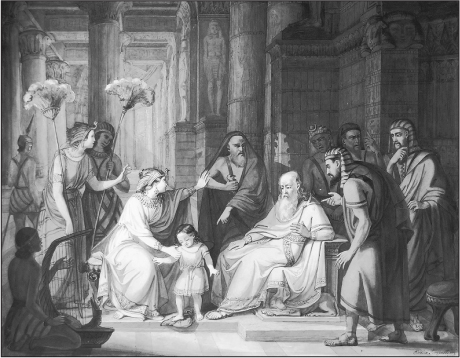

Moses Trampling Pharaoh’s Crown by Enrico Tempestini.

MOSES IN PHARAOH’S COURT. EGYPTOLOGY. HISTORICITY OF THE EXODUS. THE ‘APIRU. THE BURNING BUSH. THE GOD OF ISRAEL.

God appeared to Moses at the burning bush and instructed him to free the Israelites from slavery. But why are ancient Egyptian records silent on the subject?

Jacob’s descendants remained in Egypt and grew numerous. Eventually, a new king arose who feared this foreign population; he set out to enslave them and to prevent them from further increase. At first, he ordered the Hebrew midwives to kill any newborn boy that they delivered. The midwives, however, made an excuse not to carry out this order, so Pharaoh instead issued a general decree to the entire population to cast any newborn boy into the Nile.

It was at this time that Moses was born. At first, his mother tried to hide him, but as he grew bigger she despaired of doing so; instead, she set out to obey the king’s decree—but with a difference. She put Moses in the Nile inside a little basket. The basket floated down to where the king’s daughter was bathing, and when the daughter saw the baby, she resolved to keep it as her own. Moses grew up in the king’s court. Moses was thus raised in the very center of Egyptian royal power, the same power that he would later challenge as the leader of the Israelites.

An Evil Omen

What exactly happened in court when Pharaoh’s daughter showed up with the new baby was a subject of speculation among ancient interpreters. After all, if she had adopted Moses, it seemed likely to interpreters that she had no children of her own at the time; in that case, Moses might well have been considered a potential heir to the throne. Certainly such an idea must not have been universally welcomed. Here, thus, is an incident from Moses’ early childhood as recounted by Josephus, the first-century historian:

On one occasion, she [Pharaoh’s daughter] brought Moses to her father and showed him off and told [her father] that, having considered the royal succession—and if God did not will her to have a child of her own—then were this boy, of such godly appearance and nobility of mind, whom she had miraculously received through the grace of the river, brought up as her own, he might “eventually be made the successor to your own kingship.” Saying these things, she gave the child into her father’s hands, and he took him and, as he embraced him, put his crown on the child’s head as an act of affection toward his daughter. But Moses took it off and threw it to the ground and, as might befit a young child, stepped on it with his foot. Now this appeared to hold an evil omen for the kingdom. Seeing this, the sacred scribe who had foretold how his [Moses’] birth would bring low the Egyptian empire, rushed headlong to kill him, and crying out dreadfully, said: “This, O King, this is the child whom God had indicated must be killed for us to be out of danger! He bears witness to the prediction through this act of treading on your sovereignty and trampling your crown . . .” But Thermouthis [Pharaoh’s daughter] snatched him away, and the king, having been so predisposed by God (whose care for Moses saved him), shrank back from killing him.

Josephus, Jewish Antiquities 2:232–36

As we have seen numerous times, when ancient interpreters add something to the biblical text, it is usually because they are seeking to explain something in the original, or sometimes, because of some problem. It would not be easy to guess what was on Josephus’s mind (or rather, that of his source, since he merely transmitted this tale and did not invent it himself) if we did not have another version of it. The other version is basically similar, except for the ending. Instead of just letting Moses escape, Pharaoh’s “sacred scribe” proposes a test to make sure that the child’s gesture was meaningless:

He said to them, “[If] this child has no sense yet . . . you can verify [this] if you bring before him on a platter a piece of gold and a burning coal. If he puts his hand out for the burning coal, then he has no sense and he ought not to be condemned to death. But if he puts his hand out for the gold, then he does have sense and you should kill him.” Whereupon they brought before him a piece of gold and a burning coal, and Moses put forth his hand to take the gold. But the angel Gabriel came and pushed his hand aside, so that his hand seized the coal and he put it to his mouth with the coal still in it; [thus] his tongue was injured, and from this he became “heavy of speech and heavy of tongue” [Exod. 4:10].

Exodus Rabba 1:26

As the last line of this passage indicates, the whole problem for ancient interpreters stems from something Moses says to God much later on, at Mount Horeb, when God seeks to enlist him to speak with Pharaoh on the Israelites’ behalf. Moses at first refuses, saying, “I am heavy of speech and heavy of tongue.” Presumably, what he meant was that he was not a particularly good speechmaker; as he puts it earlier in the same sentence, “I am not a man of words” (Exod. 4:10).1 That might have been an acceptable thing for an ancient Israelite to say, but for later Jews like Josephus, or indeed for anyone in the Greco-Roman orbit, to say that you were not good at speaking was to confess that you had failed the most basic course, rhetoric, taught in the Greco-Roman educational system. It would be like a modern would-be politician saying, “I flunked out of school in fifth grade and never went back. But vote for me anyway.”

To avoid giving such an impression about Moses, interpreters preferred to understand the phrase “heavy of speech and heavy of tongue” in some other way: what Moses must have meant was that he had some actual physical problem—a speech impediment. But would God have caused his future chosen servant to be born that way? Instead, ancient interpreters created the scenario with the burning coal to account for Moses’ speech problem.

Other interpreters, while not citing this story, went out of their way to assert that Moses, far from a high school dropout, had actually had a wonderful Egyptian education:

[Moses says:]

Throughout my boyhood years the princess did,

For princely rearing and instruction apt,

Provide all things, as though I were her own.

Ezekiel the Tragedian, Exagoge 36–38

Arithmetic, geometry, the lore of meter, rhythm, and harmony, and the whole subject of music . . . were imparted to him by learned Egyptians. These further instructed him in the philosophy conveyed in symbols . . . He had Greeks to teach him the rest of the regular school course, and the inhabitants of the neighboring countries for Assyrian literature and the Chaldean science of the heavenly bodies.

Philo, Life of Moses 1:23

Pharaoh’s daughter adopted him and brought him up as her own son, and Moses was educated in all the wisdom of Egypt, and he was powerful in his words and actions.

The Birth of Egyptology

Thus began the life of the man who was to lead the Israelites from Egyptian slavery to freedom in their ancestral homeland of Canaan. The story of Moses’ life frames not only the book of Exodus, but the next three books as well, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy. In a sense, one might say, he is the most important figure not only of the Pentateuch but of the whole Hebrew Bible. Modern scholars have thus been eager to find out all they can about the person of Moses and the history of ancient Egypt in which his story unfolds.

The interest in ancient Egypt does not come from biblical scholars alone, however, nor is it solely a concern of modern investigators. Egypt has long been a subject of fascination to outsiders, ever since classical Greece and Rome. Indeed, Greek writers had often described Egypt as the font of ancient wisdom (the Greeks saw themselves as relative newcomers in this field); Greek and Latin historians were generally admirers of all things Egyptian. Later on, during the Renaissance, these classical writings served as a kind of countertradition to the mostly negative image of Egypt in the Bible. One thing that particularly attracted people to Egyptian lore was its association with the world of the occult and secret religious teachings—so much so that Renaissance scholars in Italy and elsewhere devoted themselves to trying to piece together what they could of ancient Egyptian religion from scattered Greek fragments (and later forgeries). In particular, the Egyptian writing system, dubbed “hieroglyphics” (Greek for “priestly carvings”), fascinated people, since it seemed to hold the key to this world of lost teachings. But no one could read those ancient signs.2

All this changed following Napoleon’s expedition to Egypt at the end of the eighteenth century. A French officer with the expedition, Pierre Bouchard, discovered a large basalt stele inscribed, it turned out, with three parallel versions of the same text, a decree issued by Ptolemy V of Egypt written around 196 BCE. The three versions were written in Greek, Demotic,33 and hieroglyphic script. This was the famous Rosetta Stone, and it at last offered the hope that hieroglyphics could be understood through direct comparison of those incomprehensible signs with the other two versions of the text.

The man who was to do much of the work—and who is often called the “father of Egyptology”—was a brilliant young Frenchman named Jean-François Champollion. Since his childhood, Champollion had been fascinated with the ancient Near East; he had a gift for learning languages and went on to study, among others, Hebrew, Arabic, Persian, Aramaic, Syriac (a form of Aramaic), and even Chinese. But his passion soon became Coptic, the language still spoken by a religious minority in Egypt. During his early studies at Grenoble, Champollion had made the acquaintance of a Syrian monk who had spent time in Egypt. The monk reported favorably the Copts’ own claim that their language was actually a later form of the now-lost language of ancient Egypt; he urged Champollion to study that language as well. The young man followed this advice and soon authored a paper offering evidence in support of the Coptic-is-ancient-Egyptian hypothesis, which he submitted to the Academy of Grenoble in 1807. He was sixteen years old.

Appointed a professor at Grenoble at the age of nineteen, he set himself to deciphering the ancient Egyptian writing system with the aid of the Rosetta Stone. It was no easy matter: while some of the symbols were, as people had long maintained, signs representing whole words, others seemed to be alphabetical. Champollion deduced this from the fact that some hieroglyphs were apparently used to represent proper names in the Greek version of the text. Eventually, he was able to show that 486 Greek words on the Rosetta Stone corresponded to 1,419 hieroglyphs—surely, these hieroglyphs functioned like letters and not whole words! But the writing system was difficult to crack, not only because of the mixture of whole-word symbols and individual-sound symbols, but because the same sound was sometimes represented by two different symbols. In addition, it turned out that vowel sounds were not fully represented in writing: the Greek Ptolemaios came out Ptolmys, for example.

Champollion was not the only one in pursuit of ancient Egyptian; notably, he had a British rival, Thomas Young, who published some of his discoveries even before Champollion and on which the young Frenchman built some of his own conclusions. But Champollion ultimately pulled ahead of his competitor. He not only expanded and refined his grasp of hieroglyphics, but he soon published studies of ancient Egyptian religion and the Egyptian pantheon; his work on a royal papyrus from the time of Rameses II led him to revise then-current ideas of Egyptian history and the arrangement of dynasties. His appointment in 1826 to head the Egyptian section of the Louvre Museum in Paris allowed him firsthand access to the treasures brought back from the Napoleonic expedition; then, in 1828, he traveled to Egypt itself, where he was able to study texts in situ. He returned a year and a half later with copious notes that would ultimately lead to the publication of his Egyptian grammar, an Egyptian dictionary, and his Monuments of Egypt and Nubia. But these were all posthumous publications; Champollion himself died in 1832, at the age of forty-one.

Nowadays, thanks to the pioneering work of Champollion and others, scholars have a detailed picture of ancient Egypt—not only its own history, including the names and dates of its kings, its religion, social and political organization, and daily life, but also what Egyptians reported in various periods about other nations in the region. In addition to actual texts, archaeologists have also uncovered some of the main cities of ancient Egypt, with their temples, palaces, and other monumental architecture. The study of all this material, Egyptology, is nowadays recognized as an important academic discipline in its own right—and, of course, it is important to the study of the biblical world as well.

When it comes to the events described in the book of Exodus, however, Egyptology seems to draw a blank. No ancient Egyptian text discovered so far describes anything like the ten plagues that are said to have afflicted Egypt in the biblical account, nor is there any mention of a mass exodus of foreign slaves at that time. It may be that no evidence has been found because these events were not deemed particularly flattering from an Egyptian standpoint; still, this total silence is troubling for those who wish to see in the Bible a report of actual, historical events.3 And the doubts raised by this silence are not the only thing calling into question the historicity of the biblical account.

Historicity of the Exodus

Even in ancient times, some people wondered about the factual side of the Exodus story. The Jewish writer Josephus reports on “libels against us” spread by unsympathetic historians in connection with the exodus; their claim was that the Jews were not freed by God but expelled as undesirables by the Egyptian king, who saw to it that they were ushered out of the country in the company of some Egyptian lepers and other personae non gratae.4 While it is true that such writings were doubtless motivated by openly anti-Jewish animus,5 elements in the biblical account itself no doubt encouraged such writers to create their alternate version of the events. Josephus himself sounds just a touch skeptical about the miraculous dividing of the Red Sea:

Each of the things I have recounted just as they are told in Sacred Scripture. And let no one wonder at the astonishing nature of this thing, that a road to safety was found through the sea itself—whether [this happened] by God’s will or simply through happenstance—on behalf of an ancient people innocent of all wrongdoing. For indeed, it was but a short while ago that the Pamphilian Sea moved backwards for those who were accompanying Alexander, king of Macedonia, thus offering them a path through it when no other way out existed, and so [allowing them] to overcome, as was God’s will, the Persian empire. All those who have written down Alexander’s doings are in agreement on this. However, each person may decide on his own concerning such matters.

Josephus, Jewish Antiquities 2:347–48

Quite apart from the miraculous events recounted—the ten plagues and the splitting of the Red Sea—people have wondered how six hundred thousand male Israelites, along with their wives, children, flocks, and herds, could have survived in the desert for forty years; the numbers seemed impossibly large for a group traveling together from tiny oasis to tiny oasis. In our own day, the silence of ancient Egyptian records has been compounded by the silence of archaeologists: many of the sites mentioned in the account of the Israelites’ desert wanderings have been identified and excavated, but none of them has yielded anything that could be construed as attesting to the presence of such a mass of Israelites (or even of a considerably smaller group). What is more, as we shall see, the possibility of a subsequent mass entry of Israelites into Canaan is equally difficult to support, both with regard to the archaeological record and in view of some apparent contradictions within the Bible itself. On top of this, archaeologists have found no evidence of Egyptian influence in the earliest settlements in Canaan identified as Israelite: they are not laid out like Egyptian villages, and the Israelites who lived there did not use Egyptian-style tools or pottery or script—in short, there is nothing to indicate that the earliest Israelites had had any sustained, firsthand contact with life in Egypt.6 Thus, as one popular survey recently noted, “The conclusion . . . that the exodus did not happen at the time and in the manner described in the Bible . . . seems irrefutable.”7 Another researcher’s denial is even more sweeping: “Not only is there no archaeological evidence for an exodus, there is no need to posit such an event. We can account for Israelite origins, historically and archaeologically, without presuming any Egyptian background.”8

But not so fast! Even if modern scholars have doubts about the numbers involved and other aspects of the biblical account, various details in the Exodus narrative do seem to many to have the ring of authenticity.

There is, to begin with, the matter of names. If some Israelite in a later day were making up this story out of whole cloth, it is difficult to understand why he would have given the story’s great hero an Egyptian name. Moses is clearly that. Many Egyptian names combine the particle -mose (“is born”) with the name of a god, thus: Thutmose (“Thut is born”), Ramose (“Ra is born”—this is the same name as Rameses in the Bible), and so forth. What is more, sometimes the divine name is dropped from such compounds, so that plain old mose, Moses, appears to be an altogether plausible Egyptian name.9 Of course, the biblical narrative claims that Moses’ name comes from a Hebrew word that means “drawn up [from water]” (Exod. 2:10), but this etymology is hardly credible to modern scholars. (Why would an Egyptian princess give her adopted son a newly minted Hebrew name—and how would she know enough Hebrew grammar to do so?)

Nor is Moses the only Egyptian name in the group. The name Phinehas (Exod. 6:25) is also of Egyptian origin (“southerner,” hence also “dark-skinned one”), as perhaps are the names of Moses’ brother and sister, Aaron and Miriam.10 To be sure, I could make up a story about a group of Americans being led out of Mexico by Juan, José, and Maria; these names will all be found to be authentically Mexican, but that does not mean that my story is true, or even based on a firsthand knowledge of Mexico. But if my story claimed that these leaders were in fact Americans, why wouldn’t I have simply called them John, Joe, and Mary Jane? In fact, why would I have said José was called José because his parents were fond of a patriotic American anthem that began, “José, can you see”? (This, a modern scholar would say, is roughly the equivalent of deriving the name Moses from “drawn up [from water].”) One is thus left with the conclusion that the exodus tradition preserved in the Bible must have been connected from an early point with a group of indelible Egyptian names—despite the fact that that tradition had absolutely no interest in claiming that the people involved were anything but pure-blooded Israelites. Does this not suggest that there really was someone named Moses connected with some sort of exodus, and that, whatever else in the story may have been invented, his real name could not be suppressed later on because it was simply too well known?

Some of the Exodus place-names, too, bear the stamp of authenticity. Thus, the Israelite slaves are said to have built the cities of Pithom and Raamses (Exod. 1:11). The first of these represents the Egyptian city P(r) ’Atm, “House of [the god] Atum,” while the second is P(r) R‘mss, “House of Rameses,” a city that was built by Rameses II (1290–1224 BCE). For this and other reasons, historians date the exodus to the time of this king, or possibly that of his son, Merneptah, that is, to the mid-to-late thirteenth century BCE, which fits fairly well with the overall chronology of this early period.11 What is more, an ancient Greek historian, Diodorus Sicilus, reports the tradition that a certain king “Seoösis”12 went out of his way to use foreign workers in his building projects rather than employing native Egyptians: “On these labors he used no Egyptians, but constructed them all by the hands of his captives alone.”13 This, too, fits with the Exodus account. Indeed, calling the Egyptian king at the time of the exodus by the title “Pharaoh” is another apparently authenticating detail. This word (pr‘3) actually means “Big House” in Egyptian, namely, the royal palace; in the eighteenth dynasty, however, it came to be used as a way of referring to the king himself—somewhat similar to the way American press reports sometimes say, “The White House announced today . . .” Again, this would seem to put the Exodus account in the proper time frame.14 And on top of this is the matter of the ‘apiru.

The ‘Apiru

It was said above that the Egyptian records do not speak of the Israelite slaves. One text, however, Papyrus Leiden 348, speaks of some ‘apiru who were used for “hauling stones to the great pylon” of one of the public structures in the city of Rameses (that is, P(r) R‘mss).15 Who were the ‘apiru? This has been the subject of much speculation among ancient Near Eastern scholars. The name appears in various forms in different languages, notably ![]() abiru in Akkadian (also represented by the Sumerian ideogram SA.GAZ) and ‘pr (=‘apiru) in Ugaritic (a northern brand of Canaanite); the ‘apiru have also been found in Hittite texts. Because of the sound similarity, a case can be made that this word is none other than the Hebrew word ‘ibri, “Hebrew.”16

abiru in Akkadian (also represented by the Sumerian ideogram SA.GAZ) and ‘pr (=‘apiru) in Ugaritic (a northern brand of Canaanite); the ‘apiru have also been found in Hittite texts. Because of the sound similarity, a case can be made that this word is none other than the Hebrew word ‘ibri, “Hebrew.”16

As scholars have come to understand, ‘apiru itself cannot mean just “Hebrew”: there are too many texts (over 250) written over too broad a historical period and too wide a geographical area to make this even remotely plausible.17 Most scholars nowadays identify ‘apiru as designating a (low) social class, or possibly referring to a category of refugees or escapees from another country (the two ideas are not mutually exclusive). But the texts are hardly uniform in their use of the term: Old Babylonian texts refer to the ‘apiru as mercenaries employed by the state, whereas the Mari texts and the El Amarna letters34 seem to present the ‘apiru as outlaws or highwaymen.

What is striking to scholars, however, is the possibility that later tradition still preserved the derogatory word ‘apiru as how the Israelites (and perhaps others) were known to the Egyptians in the late second millennium. The evidence is in the Bible itself. Contrary to popular expectation, the word “Hebrew” actually does not appear very much in the Bible. What we call the Hebrew language, for example, is never called that in the Hebrew Bible; instead, it is called “Judean” or “Canaanite.” Nor are the people of Israel generally called Hebrews. But here and there, thirty-four times in all, the word “Hebrew” does occur in this sense, and of these, fully twenty of the occurrences are found in the context of the story of the Exodus or the preceding narrative of Joseph. Thus, Pharaoh calls to the “Hebrew midwives” to do his bidding (Exod. 1:15), and when Pharaoh’s daughter finds a little baby floating in the Nile she says, “This must be one of those Hebrew children” (Exod. 2:6). After he is grown, Moses sees “two Hebrew men fighting,” and when he returns to Egypt he tells Pharaoh, “The God of the Hebrews appeared to us” (Exod. 5:3). All this may suggest that these ancient texts preserve the tradition that “Hebrew” is what the Egyptians themselves called the Israelites.18 If so, the absence of direct reference to the Israelite slaves in Egyptian documents might be somewhat less troubling; indeed, the mention of the ‘apiru in Papyrus Leiden 348 might actually seem to provide something like the smoking gun biblical scholars are looking for. True, this is only one text, and one robin doth not a springtime make; indeed, even this text may be talking about some other bunch of ‘apiru quite unrelated to the biblical Israelites. But it does say that the ‘apiru were used for building part of the city of Rameses, which is exactly what the Bible says of the Israelites in Exod. 1:11. Beyond this, it is to be noted that the ‘apiru do not appear in firsthand reports in the ancient Near East after the end of the second millennium: if the book of Exodus uses this name for the Israelites in Egypt, it would seem to be basing itself on usage appropriate to the presumed time of the Exodus, or pretty close to it, in the late second millennium.

In short, the evidence that Egyptology provides is mixed. While there is no direct confirmation of the biblical account, a number of tantalizing details have led many otherwise hard-nosed modern scholars to conclude that there may be at least some historical basis to the biblical account of the Exodus—even if, as we shall see, most such scholars believe it involved only a small part of what was to become the nation of Israel. Beyond the onomastic (that is, concerning proper names) and other linguistic evidence is an argument of somewhat larger dimension, namely, the nature of the overall message imparted by the Exodus narrative. For, as numerous writers have already pointed out, this is not exactly the sort of story a people would be likely to make up about itself out of whole cloth—“We were a bunch of low-class construction workers and domestic slaves for our neighbors to the south until, after repeated negotiations, they allowed us to leave and come here.” Usually, myths of national origin try to strike a more heroic note—from Romulus and Remus and pius Aeneas to Arthurian Britain and doughty Vercingetorix, national myths tend to stress all that is positive and noble in their country’s founding.19 The Exodus account is not exactly lacking in heroism, but it seems to scholars more like the heroic recasting of a not particularly flattering set of facts than the sort of thing that would be simply invented.20

From the Bulrushes

This is not to say, of course, that nothing in the Exodus narrative appears to modern scholars to have been invented. The story of Moses being found in the bulrushes by the Egyptian princess has suggested various parallels in the mythical literature of Egypt and Mesopotamia. Here, for example, is a (fictional) account of the birth of Sargon I of Agade (ca. 2371–2316 BCE) as reconstructed from some much later cuneiform texts:

[Sargon speaks:] I am the child of a priest and an unknown pilgrim from the mountains. Today, I rule an empire from the city of Agade.

Because my mother did not want anyone in the city of Asupiranu to know that she had given birth to a child, she left me on the bank of the Euphrates river in a basket woven from rushes and waterproofed with tar. The river carried my basket down to a canal, where Akki, the royal gardener, lifted me out of the water and reared me as his own. He trained me to care for the gardens of the great king.

With the help of Ishtar, divine patron of love and war, I became king of the black-headed people and have ruled for fifty-five years.21

The motif of a newborn child being exposed to the elements and left to fend for itself is found in many places around the world (and no doubt had some connection with gruesome reality—such exposure was usually, in effect, a form of infanticide). Still, scholars have been struck by the similarity of the Sargon legend with the biblical account of Moses’ birth—the basket of reeds waterproofed with tar (Exod. 2:3), a stratagem that enables the child to be saved by a member of the royal court and brought up there (Exod. 2:10). Once again, it looks to scholars as if the Bible has taken a leaf from the literature of its neighbors.

The Burning Bush

Growing up in Pharaoh’s court, Moses apparently knew of his Israelite origins. At one point, Scripture recounts, He “went out to his people” (Exod. 2:11) and his heart was turned to the Israelites’ suffering. On a certain occasion, he saw an Egyptian man beating a Hebrew; Moses came to the rescue and killed the Egyptian. When word of the deed spread, Moses feared for his life and fled to nearby Midian. There he met and married Zipporah, daughter of Jethro, the priest of Midian. He settled down to a life of comfortable tranquillity as a shepherd in Midian—until his fateful encounter with God.

Moses was keeping the flocks of his father-in-law Jethro, the priest of Midian; he led his flock beyond the wilderness, and came to Horeb, the mountain of God. There the angel of the LORD appeared to him in a flame of fire out of a bush; he looked, and the bush was all ablaze, yet it was not being burned up. Then Moses said, “I must turn aside and get a look at this great sight, and see why the bush is not burned up.” When the LORD saw that he had turned aside to see, God called to him out of the bush, “Moses, Moses!” And he said, “Here I am.” Then he said, “Do not come any closer! Take your shoes from off your feet, for the place on which you are standing is holy ground.” He said further, “I am the God of your father, the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob.” And Moses hid his face, for he was afraid to look at God.

Then the LORD said, “I have seen the misery of my people who are in Egypt; I have heard how they cry out on account of their taskmasters; yes, I know about their sufferings. So I have come down to save them from the Egyptians, and to take them up out of that land to a good and broad land, a land flowing with milk and honey, to the country of the Canaanites, the Hittites, the Amorites, the Perizzites, the Hivites, and the Jebusites. In short, the cry of the Israelites has come to me and I have also seen how the Egyptians are oppressing them. So come now, I wish to send you to Pharaoh to take my people, the Israelites, out of Egypt.” But Moses said to God, “Who am I that I should go to Pharaoh and take the Israelites out of Egypt?” He said, “I will be with you; and this is the guarantee that I am the one who is sending you: after you have brought the people out of Egypt, you will worship God on this mountain.”

But Moses said to God, “Suppose I do go to the Israelites and say to them, ‘The God of your fathers has sent me to you,’ then they will say to me, ‘What is His name?’ What can I say to them then?” Then God said to Moses, “I am who I am.” He said: “This is what you will tell the Israelites, ‘I am has sent me to you.’” Then God said further to Moses, “This is what you will tell the Israelites, ‘The LORD, the God of your ancestors, the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob, has sent me to you’: This is My name forever, by this shall I be known for all generations.”

In order to understand this passage, it is well to remember that its God is not the God of later biblical times, the omnipresent, omniscient deity; instead, this is the God of Old (above, chapter 7). Such a God dwells (when He is in the world at all) in a specific spot, what the first sentence calls “Horeb, the mountain of God.” Apparently, Moses has never been to this mountain before—it must have been in a somewhat remote area. That is why the passage starts off by explaining the special circumstances that led him to this mountain at this time: he had led his flock “beyond the wilderness,” some greater distance than usual, presumably in search of a good grazing site.

At this point he sees an odd sight, a desert shrub that has caught fire and continues to burn and burn. The fact of the fire itself is not surprising—bushes (if indeed that is what it was)22 are proverbially dry in the Bible, and, set off by a spark or by lightning, they catch fire easily (see, for example, Judg. 9:15). But usually they burn out just as quickly—their spindly little branches cannot support any long-lasting flame (Eccles. 7:5–6). In this case, however, Moses has apparently seen the smoke from afar, and, as he draws closer, he is surprised to see that the flames are still flickering. So he decides to turn from the path he is on and take a closer look, a step that brings him to within the area of God’s presence. The burning bush, in other words, was just a divine stratagem, a sort of “Yoo-hoo! Over here!” to bring Moses to that precise place. Once God sees that Moses is there, He can address him directly and tell him what is really happening. “Take off your shoes; this is holy ground,” He says—in other words, you are not just anywhere anymore, Moses; you have entered My spot.

In keeping with what was said in chapter 7, it is interesting to note how the “angel of the LORD” slides effortlessly here into being simply “the LORD” in a matter of two sentences. At first, Moses is still in ordinary reality, but then, in a twinkling, he is in the midst of the extraordinary—and he is afraid. God then tells him, in the long and complicated middle paragraph above, how He wants Moses to go back to Egypt and take the Israelites from their suffering; but Moses is reluctant, despite God’s assurances.23 The text presents Moses as reluctant because, as we shall see, any ancient Israelite would expect him to be under the circumstances. When it comes to the Bible’s saying how a prophet became a prophet, the person’s reluctance to take on the job is often mentioned; apparently, it was important for people to know that such a trusted figure had not been a self-promoter. This is true, as we shall see, of Samuel and Isaiah and Jeremiah, and it is true of Moses here: God tells him what He wants him to do, and Moses tries to say no. In fact, the exchange quoted above is just the beginning. Moses continues to defer and dither for the rest of the chapter, offering one excuse after another (including being “heavy of speech”), and God continues to insist. Finally, after much back-and-forth, Moses pleads: “O my Lord, just send someone else!” (Exod. 4:13).

In his initial casting about for an excuse, Moses hits upon the fact that he himself does not know the specific name of this God. God had introduced Himself by saying, “I am the God of your father, the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob,” but He had not said what His name was. Of course, Moses is curious about the name, but he is also playing for time; he is frightened, but also intrigued. Who is this God, and what is happening to me? So he presents his question not as a real question but as an objection: “If I tell the Israelites that You appeared to me, the first thing they will ask is: ‘What was His name?’ Since I do not know the answer to that, I cannot possibly accept this mission.”

To this question God responds with a polite “None of your business”: I am who I am, He says, and this is reminiscent of the answer that the angel gave to Jacob after their fight, “Why should you be asking my name?” (Gen. 32:29), and the answer that Manoah got from his angel, “Why should you be asking my name, since it is unknowable?” (Judg. 13:18). In this case, however (as almost every biblical commentator since ancient times has pointed out), God’s refusal to answer—“I am who I am”—nevertheless contains a clue to the true answer anyway, since I am in Hebrew (’ehyeh) sounds something like God’s name (YHWH). So, God tells Moses, you won’t be far wrong if you tell the Israelites, “’Ehyeh has sent me to you.” Moses is apparently still a bit confused, since, after a silence,24 God then explains in the next sentence, “This is what you will tell the Israelites, ‘The LORD [that is, YHWH] . . . has sent me to you.’” Moses thus does get the answer he is looking for, and eventually he even accepts the mission.

To say only this, however, is to miss something essential about this whole passage. After all, what it describes is nothing less than the moment when Moses’ whole life changed. Up to this point, things had been going pretty well for him. True, he had had to flee his native Egypt, but now he was comfortably settled in Midian, married to the daughter of one of its most prominent citizens, with nothing more to do all day than take care of his father-in-law’s substantial flocks. All the turmoil he had witnessed in Egypt was now far behind him; he was in new, far more tranquil surroundings. We do not know how old he was,25 but presumably he was still a fairly young man, since this incident occurs just after his marriage and the birth of his sons (Exod. 2:21–22). So it is surely no accident that, when God summons him to return to Egypt, he answers the way he does: “Who am I that I should go to Pharaoh and take the Israelites out of Egypt?” Who am I is indeed the question of a still-young man, not at all sure of the course his life may take. And so, God answers him in kind: “You wish to know who you are? I will tell you: I am. ‘I-am’ is sending you to Egypt.” Staring into the crackling flames, Moses suddenly has an answer to both the questions he asked, “Who am I?” and “Who are You?”—and in that glimmering moment, the two answers seem to have come together.

One might at this point take a step backward and consider how the Bible is telling its story. Clearly, this account of Moses and the burning bush is not what we have seen numerous times in the book of Genesis, a schematic narrative. It could have been. If the whole point were simply to evoke the standard theme of a prophet’s initial refusal of his mission, then this text could have simply said, “God told Moses to go to Egypt. Moses wept and pleaded and said, ‘Send someone else,’ but God insisted and said, ‘No, but I will send you,’ and so Moses went.” Instead, the narrative is apparently interested in taking its time and telling a more complicated story, inviting us, as it were, to participate in it and appreciate the full weight of this moment. But why? Or, to ask the modern scholar’s question: Who is writing this, and for what purpose? Does the text say what it says because, at this stage of things, telling a story is no longer a matter of relating “just the facts, ma’am”? Or was there something special, something particularly deserving of weight, in this particular moment of the story?

Philo at the Burning Bush

For the most part, we have looked at ancient interpreters to see how different their approach to the biblical text is from that of modern interpreters, as well as to show how they reckoned with one or another problem they perceived in the text. But this is hardly all there is to say about ancient interpreters. Here is how Philo of Alexandria retells the same passage seen above:

There was a bush, a thorny, puny sort of plant, which, without anyone setting it on fire, suddenly started burning and, although spouting flames from its roots to the tips of its branches, as if it were a mighty fountain, it nonetheless remained unharmed. So it did not burn up, indeed, it appeared rather invulnerable; and it did not serve as fuel for the fire, but seemed to use the fire as its fuel. Toward the very center of the flames was a form of extraordinary beauty, which was like nothing seen with the eye, a likeness of divine appearance whose light flashed forth more brightly than the fire, and which one might suppose to have been an image of the One Who Is [God]. But let it rather be called an angel [that is, a herald], for, with a silence more eloquent than any sound, it heralded by means of a sublime vision things that were to happen later on. For the bush was a symbol of those who suffer the flames of injustice, just as the fire symbolized those responsible for it; but that which burned did not burn up, and those who suffered injustice were not to be destroyed by their oppressors.

Philo, Life of Moses 1:65–67

In the biblical narrative, as noted above, the burning bush serves as a way of attracting Moses’ attention and so bringing him to the very foot of the “mountain of God,” where God can address him. For Philo, however, such an interpretation was impossible. As far as he knew, God is everywhere; what need was there for Him to lead Moses to one spot or another? But then, if that was so, what was the purpose of this burning bush? Why did not God speak to Moses back in his own house, or in a dream at night, and tell him what He wanted? And so, for Philo and other interpreters, the whole story of the burning bush had to assume a different character.

For this purpose, Philo has stacked the deck a bit. He says that the bush was a “puny sort of plant,” though there is nothing in the Bible to suggest this. Such puniness might make one think that the fire would make short work of this bush, but Philo says (again, going beyond the biblical description) that the bush “remained unharmed” and “appeared . . . invulnerable,” indeed, “seemed to use the fire as its fuel.” He says all this not particularly to aggrandize the miraculous nature of the sight, but in order to turn it into a symbolic message: the bush symbolizes the people of Israel, and the fire their Egyptian overlords. The fact that the bush keeps burning thus symbolizes for Philo the message that the Israelites will survive despite their oppression; indeed, they will triumph. That is why Philo says that the bush spoke to Moses “with a silence more eloquent than any sound.” According to Philo’s interpretation of the passage, Moses walks up to the bush, stares at it in silence for a minute or two, and then says, “Oh I get it! You want me to go back to Egypt and free the Israelites.”

It is interesting how Philo enlists a little “flaw” in the biblical text to the service of this interpretation. We noted above how the text started off by saying that the “angel of the LORD” appeared to Moses, but then, two sentences later, it is no longer an angel but God Himself. That was fine for the early biblical period, the time of the God of Old, but by Philo’s day, an angel was altogether different from the infinite and omnipresent God. Under other circumstances, perhaps, Philo might have simply said the angel was speaking on behalf of God and, for that reason, the text stopped saying “angel of the LORD” after the first mention and simply referred thereafter to God Himself. But the word “angel” in Greek, angelos, also means “announcer” or “herald.” Such a meaning suited perfectly Philo’s symbolic understanding of the burning bush: it was a visual announcement, a heralding of the fact that the Israelites would withstand their oppressors. Therefore, instead of saying that “God” or “LORD” in the rest of the passage is really a shorthand for “angel of the LORD,” Philo says the exact opposite: this was actually a direct meeting between God and Moses, and if the Bible says that Moses saw an angel, it does not mean angel in the conventional sense, but only that Moses saw a sight—a bush that burned but did not burn up—that announced what would be in the future.

The Name of the Lord

Before we leave Mount Horeb, a word about the divine name hinted at in God’s “I am who I am.” The origin of the divine name YHWH, and its connection to the verb “to be” in Hebrew (hwh or hyh) has long fascinated biblical interpreters.26 One rabbinic tradition understood “I am who I am” as if addressing the future: I will be with Israel in this time of trouble just as I will be with them in later difficulties (not very reassuring!). When the Greek-speaking Jews of Alexandria translated the passage of Moses and the burning bush, they rendered God’s words “I am who I am” as “I am the One who is,” or, “I am the Being One.” This is of course not what the text says, but it pleased Hellenistic Jews of Neoplatonic sensibilities to suggest that the very essence of this God is His connection with existence itself. For Philo this translation became, as it were, canonical: he frequently refers to God simply as “the One who is.” It was true of others in the same period:

All men who were ignorant of God were thus foolish by nature; they could not perceive the One who is from the good things that are visible.

I am the One who is, but you consider in your heart.

I am robed with heaven, draped around with sea,

The earth is the support of My feet, around My body is poured

The air, the entire chorus of stars revolves around Me.

Sibylline Oracles 1:137–40

Grace to you and peace from Him who is and who was and who is to come.

This understanding has survived into modern times; many people believe that at the heart of the biblical idea of God is His connection with being itself. However, a number of scholars have proposed other theories about the meaning of this divine name. One of the issues is connected with the way biblical Hebrew was written: vowels, especially in the middle of words, were often left unexpressed. Since the pronunciation of this name was considered sacred, even within biblical times there was a tendency to avoid saying it, or even to substitute another respectful word for it—which is how various words meaning “lord” came to be a substitute for this name, first in Hebrew (adonai), then Greek (kurios), Latin (dominus), and in other languages. When the name YHWH itself was the subject of discussion, it was sometimes called in Greek the Tetragrammaton (four-letter name) rather than said or spelled out, and scholars still use this word today.

After a while, since Jews had ceased to pronounce the name in Hebrew, the vowels that go between the consonants were no longer known—and that, of course, has something to do with our ignorance today of what the name might mean (if anything). On the basis of bits of evidence from here and there, many modern scholars have concluded that the original pronunciation of God’s name must have been something like yah-weh—but this is not absolutely certain; besides, there are indications that an apocopated (shortened) form of the name was sometimes used, perhaps as a way of avoiding full pronunciation, perhaps not. In any case, if scholars are right in their restoration of the original vowels, then the name might seem to be in the causal form of the verb “to be,” that is, “He causes to be” (although the causative form of this verb appears nowhere else in the Bible). This too has a kind of Neoplatonic ring, and that leaves some scholars skeptical: it is difficult to understand how a deity such as the God of Old—who was not specifically associated in the earliest stages with causing all things to be—could have received such an appellation, though it is certainly not impossible. One contemporary scholar, Frank M. Cross, has connected the origin of this name with a fuller title that sometimes appears in the Bible, YHWH Seba’ot (usually translated as “the LORD of Hosts”). “Hosts” here means the hosts (or armies) of heaven, that is, the stars (sometimes identified as deities themselves). This full name would thus mean “He brings the armies of heaven into being,” suggesting that this deity is responsible for the creation of all other gods.27 However, this is highly speculative and lacking in solid evidence.

But perhaps the most striking thing about the name YHWH for modern scholars is connected to the passage just examined, Moses’ dialogue with God at the burning bush. According to what Moses says there, he apparently does not know God’s name—otherwise, why would he ask? Of course, one might suppose that long years of life in Egypt had caused all the Israelites to forget the name of their old deity; alternately, it might be that His name had heretofore been a divine secret, just like the names of the angels who appeared to Jacob and Manoah. Modern scholars, however, point to the fact that the burning bush episode seems to be the work of the text source designated E, a source that, up until this point, had been careful never to use the name YHWH. Behind these E texts, scholars believe, was a tradition to the effect that, before the time of Moses, the name YHWH was not known. Something similar appears a bit later, in a passage attributed to the source P. There God says to Moses, “I am YHWH. I appeared to Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob as El Shaddai [sometimes rendered as ‘God Almighty’], but I was not known to them by my name YHWH” (Exod. 6:2–3). Both sources thus seem to agree that God’s name somehow changed at the time of Moses (in contrast to texts from the J source, which use the name YHWH to refer to God long before the time of Moses—for example, in the story of Cain and Abel or in the J version of the flood story).

But why would God’s name suddenly change? Some scholars have suggested that the text is not talking just about a new name, but about an entirely new deity. After all, Moses is in Midian at the time that he encounters this God, in a place called, appropriately, “the mountain of God” (or possibly, “the mountain of the gods”). If this was Israel’s longtime God, “the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob,” what was He doing stationed at what seems to be His permanent home in Midian? Midian was, like its neighbor Edom, to the south and east of biblical Israel, a rugged land populated by rough-and-tumble desert nomads. Israel’s God, the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, ought to be somewhere to the north and west, in the land of Canaan proper. (It should be remembered that we are talking about the God of Old, who is not everywhere all at once. A deity that can promise the land of Canaan to Abraham ought to be the deity of that land, and the “mountain of God” on which He dwells ought likewise to be there and not in Midian.) Thus, despite the text’s insistence that YHWH is none other than “the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob,” some scholars nowadays entertain a different hypothesis: the God known as YHWH was not originally associated with the land of Canaan at all but arrived there only at a certain point, from elsewhere—specifically from the barren wastes of Edom and Midian, far to the south and east of the Israelite homeland (see Deut. 33:2; Judg. 5:4; and Hab. 3:3, 7, all of which suggest that YHWH came to Canaan from the southeast). The circumstances of this divine invasion remain to be seen a few chapters hence (and it must be conceded from the start that the evidence for this hypothesis is sparse and the scholarship rather speculative). If modern scholars are right, however, what the Bible seems to be saying here (perhaps in spite of itself) is that, at this moment on Mount Horeb, a new God walked into Israel’s life, one who ultimately changed the world’s thinking about divinity.