A Covenant with God

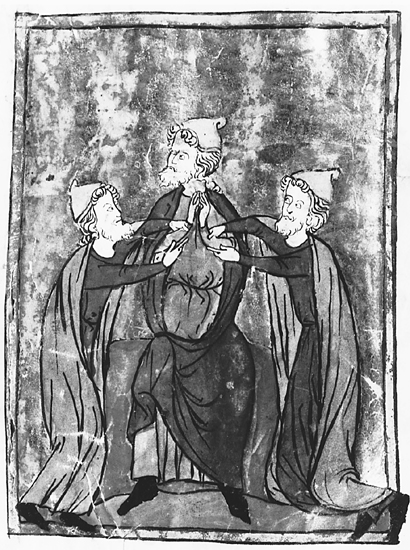

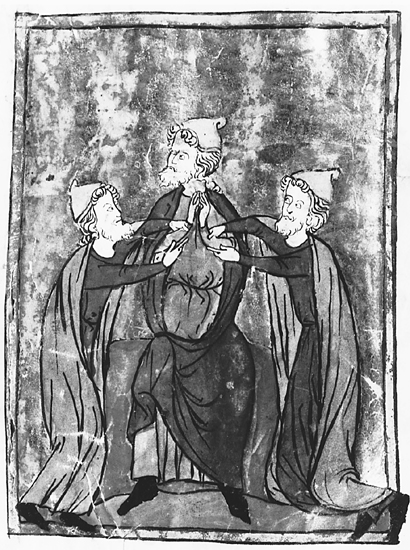

Moses, Aaron, and Hur miniature from Hebrew Pentateuch before 1300, artist unknown.

UPRAISED ARMS AT REPHIDIM. MANNA AND THE TRAVELING WELL. AN AGREEMENT WITH GOD. HITTITE TREATIES.

From Egypt the Israelites made their way to Mount Sinai, where God made a solemn pact with them. But why did He do it the way that He did?

After the Israelites had crossed the Red Sea to safety, they began the long trek toward their promised homeland, Canaan. God preceded them, as before, in a pillar of cloud that sheltered them during the day, and in a pillar of fire at night that lit their way—allowing them to travel both day and night (Exod. 13:21–22). Despite this divine presence, however, they ran into trouble almost immediately. At a place called Rephidim, they were attacked by the forces of the Amalekites, a desert-dwelling people.

Then Amalek came and fought against Israel at Rephidim. Moses said to Joshua, “Choose some men for us and go out and fight against Amalek tomorrow. I will stand on the top of the hill with the staff of God in my hand.” So Joshua did as Moses told him and fought against Amalek, while Moses, Aaron, and Hur went up to the top of the hill. Whenever Moses held up his hands, Israel prevailed; but whenever he lowered his hands, Amalek prevailed. Now Moses’ hands grew weary; so they took a stone and put it under him, and he sat on it. Aaron and Hur held up his hands, one on one side and the other on the other side; so his hands were steady until the sun set. Thus Joshua defeated Amalek and his people with the sword.

This incident is quite puzzling; in fact, it seems potentially blasphemous. It implies that Moses’ hands had some sort of magical power. But most ancient interpreters could not believe the Bible was suggesting that this had indeed been magic (and that it had worked!). Elsewhere in the Pentateuch, working magic is strictly forbidden. On reflection, it seemed far more likely that Moses’ upraised hands were meant to communicate some symbolic message:

[Moses’ hands] became by turns very light and very heavy, and whenever they were in the former condition and rose aloft, [Israel] was strong and distinguished itself by its valor; but whenever his hands were weighed down, the enemy prevailed. Thus, by symbols, God showed that the earth and the lowest regions of the universe were the portion assigned to the one party, and the ethereal, the holiest region, to the other; and that, just as heaven holds kingship in the universe and is superior to earth, so this nation would be victorious over its opponents in war.

Philo, Moses 1:217

But did Moses’ hands actually make Israel win, and was it they that crushed Amalek? Rather [this text means that] when Moses lifted his hands toward heaven, Israel would look upon him and put their trust in Him who ordered Moses to do so; then God would perform miracles and wonders for them.

Mekhilta deR. Ishmael, Amaleq 1 (see also m. Rosh ha-Shanah 3:5)

And it happened that, whenever Moses would raise his hands in prayer, the Israelites would prevail and be victorious, but when he would withhold his hands from prayer, the Amalekites prevailed.

The same general approach to this passage was passed on to Christian interpreters, but they soon saw in Moses’ upraised hands another sort of symbolic message:

The Spirit, speaking to the heart of Moses, [tells him] to make a representation of the cross and of him who was to suffer upon it. . . . So Moses . . . kept stretching out his hands, and Israel again began to be victorious; then, whenever he let them drop, they began to perish. Why? So that they might know that they cannot be saved if they do not hope in Him.

Letter of Barnabas 12:2–3

Moses prefigured him [Christ], stretching out his holy arms,

Conquering Amalek by faith so that the people might know

That he is elect and precious with God his father.

Sibylline Oracles 8:251–53

For early Christians this brief incident became particularly significant, since it was a striking demonstration that, as the Latin saying had it, quod in vetere latet in novo patet (what is hidden in the Old [Testament] is made explicit in the New). As they saw it, Moses’ hands in the form of the cross were only part of the hidden message. Surely it was not without significance that Moses himself stood to the side while his heretofore unmentioned assistant, Joshua, actually led the battle. The name Joshua in its Greek form is Jesus. Any early Christian who read the Bible in Greek simply knew that there were two biblical figures named Jesus, one in the Old Testament and one in the New. To the typologically minded, there could thus scarcely be any doubt that the Old Testament Jesus, taking Moses’ place in the lead, was a foreshadowing of the one in the New whose religion would replace that of Moses—quod in vetere latet in novo patet. What is more, Amalek scarcely seemed like an ordinary, human enemy. If he were, why should God, here and later on, single him out as Israel’s archenemy, commanding Israel to “blot out the name of Amalek from off the earth—do not forget!” (Deut. 25:19)? Amalek, Christians concluded, must symbolize the devil. Thus the fact that this Old Testament Jesus made his first appearance here, fighting the devil, while Moses stood to the side and made the sign of the cross, virtually clinched the case:

Wherever the Lord fought against the devil [that is, Amalek], the form of the cross was necessary—the cross by which Jesus was to win victory.

Tertullian, Against Marcion 3:18

The question typically asked by modern scholars—why was this story told?—receives, as so often, an etiological answer in the case of this episode. The name of the place where the battle took place, Rephidim, sounds as if it might be derived from the Hebrew root r-p-d, which means both “spread out” and “prop up.” What is more, when this place-name itself is uttered, it sounds a bit like the short phrase raphu yadayim, “the hands grew weak.” To scholars this suggests that, just as in the case of Jacob’s struggle with the angel at the Jabbok ford, a number of word associations have come together here to create the narrative: Moses spread out his hands, but then the hands grew weak, so then Aaron and Hur had to prop them up. The actual site of Rephidim is unknown today, but scholars speculate that there probably was a hill there with a large stone on it—a stone that gave rise to the element of Moses sitting as he watched the battle.1

No Water, No Food

Setting out into the wilderness, the Israelites’ main worry was food and water—both scarce in the rugged terrain. The Bible recounts that, during their forty years of wandering, the Israelites received a regular supply of a special food called manna:

Then the LORD said to Moses, “I am going to rain bread from heaven for you, and each day the people shall go out and gather enough for that day . . .”

In the morning there was a layer of dew around the camp. When the layer of dew lifted, there on the surface of the wilderness was a fine flaky substance, as fine as frost on the ground. When the Israelites saw it, they said to one another, “What is it? [man hu’, suggesting the name manna].” They did not know what it was. Moses said to them, “This is the food that the LORD has given you to eat.”

The house of Israel called it manna; it was like coriander seed, white, and the taste of it was like wafers made with honey . . . The Israelites ate manna forty years, until they came to a habitable land; they ate manna, until they came to the border of the land of Canaan.

Most modern scholars do not doubt that this description corresponds to something in the natural world. Some have identified manna with an edible substance used by today’s desert Bedouin as a sweetener: this wilderness “honeydew” is excreted by insects and plant lice after ingesting the sap of tamarisk trees. But for ancient interpreters, manna was altogether miraculous: its supernatural quality was confirmed by the fact that it came in a double portion on Fridays, obviating the need to collect manna on the sabbath (Exod. 16:22–26). It thus became, for both Christians and Jews, one of the principal elements in the Exodus narrative, lovingly embellished in ancient retellings of the story.2

Water was no less of a challenge. From the time they left Egypt, the Israelites found drinking water in short supply, and almost immediately God had to intervene to provide miraculously for their needs (Exod. 15:22–25). Then, at Rephidim (before the Amalekite attack), the people found themselves without water a second time:

They camped at Rephidim, but there was no water for the people to drink. The people quarreled with Moses, and said, “Give us water to drink.” Moses said to them, “Do not quarrel with me, and do not test the LORD!” But the people thirsted there for water; and the people complained against Moses and said, “Why did you bring us out of Egypt, to kill us and our children and livestock with thirst?” So Moses cried out to the LORD, “What shall I do with this people? Any more and they will stone me!” The LORD said to Moses, “Pass in front of the people and take some of the elders of Israel with you; and when you go, take in your hand the staff with which you struck the Nile. I will be standing there in front of you on the rock at Horeb. Then you will strike the rock, and water will come out of it, so that the people may drink.” Moses did so, in the sight of the elders of Israel. The place was then called Massah [“test”] and Meribah [“quarrel”], because the Israelites quarreled and tested the LORD, saying, “Is the LORD among us or not?”

This was certainly an extraordinary happening—causing water to flow forth from a rock—but, as it turned out, it was not an entirely unique occurrence. Sometime later (the Bible does not say when, but arguably toward the end of the Israelites’ forty years of wandering), the people come to a new place, Kadesh, and something rather similar happens:

Now there was no water for the congregation; so they complained against Moses and against Aaron. The people quarreled with Moses and said, “Would that we had died when our kindred died before the LORD! Why have you brought the assembly of the LORD into this wilderness for us and our livestock to die here? Why have you brought us up out of Egypt, to bring us to this wretched place? This is not the place of grain and figs and vines and pomegranates [you told us about]; there is not even any water to drink!” Then Moses and Aaron went away from the assembly to the entrance of the tent of meeting and they fell on their faces; then the glory of the LORD appeared to them.

The LORD spoke to Moses, saying: Take the staff, and assemble the congregation, you and your brother Aaron, and command the rock before their eyes to yield its water. Thus you shall bring water out of the rock for them and provide drink for the congregation and their livestock.

So Moses took the staff from before the LORD, as He had commanded him. Moses and Aaron gathered the assembly together before the rock, and he said to them, “Listen, you rebels, shall we bring water for you out of this rock?” Then Moses lifted up his hand and struck the rock twice with his staff; water came out abundantly, and the congregation and their livestock drank . . . These are the waters of Meribah [“quarrel”], because the people of Israel quarreled with the LORD, and then He showed his holiness by means of them [the waters].

At first glance this might simply appear to be a second occurrence of the same sort of miracle; again there was a rock handy, and again Moses was ordered to extract water from it. If a similar miracle occurred twice, that was apparently because the same set of circumstances (the people complaining about the lack of water) had come up again. But if so, why did Scripture now say that “these are the waters of Meribah”; weren’t the waters of Meribah back in Rephidim, many miles to the west? Interpreters noticed another thing as well: from the time when Moses had struck the rock at Rephidim, in the book of Exodus, to this moment at Kadesh, in the book of Numbers, there had not been a word about the Israelites lacking water. At the same time, Scripture did not report on their reaching any new oasis or digging any new wells.

The more interpreters considered the matter, the more what must at first have seemed an unlikely explanation now recommended itself. If, in the time that separated the incidents at Rephidim and Kadesh, the Israelites had not lacked for water—neither they nor their considerable livestock—it must have been that they continued to have their needs supplied by that very same rock that Moses had struck. This was their source of drinking water for a full forty years. And if Scripture said that the “waters of Meribah,” which had been located at Rephidim, were now found at Kadesh, that must mean that the rock that provided those waters had somehow moved (or been transported) from Rephidim to their present location, so as to be constantly in proximity of the Israelites and their flocks.

Thus was born the tradition of the traveling rock that followed Israel in its desert wanderings for forty years:

Now He led His people out into the wilderness; for forty years He rained down for them bread from heaven [manna], and brought quail to them from the sea, and brought forth a well of water to follow them.

And it [the water] followed them in the wilderness forty years and went up to the mountains with them and went down into the plains.

Pseudo-Philo, Book of Biblical Antiquities 10:7; 11:15

I want you to know, brethren, that our fathers were all under the cloud, and all passed through the sea, and all . . . drank the same spiritual drink. For they drank from the supernatural Rock which followed them, and the rock was Christ.

And so, the well that was with Israel in the desert was like a rock the size of a large container, gushing upwards as if from a narrow-neck flask, going up with them to the mountains and going down with them to the valleys.

Tosefta Sukkah 3:11

Interpreters noticed another thing about this traveling rock. Its waters seem to have given out right after the death of Miriam, Moses’ sister (Num. 20:1); the very next verse begins the account of the lack of water seen above (Num. 20:2), and this shortage apparently occurred again (Num. 20:19) and again (Num. 21:5). Post hoc propter hoc: it seemed from the juxtaposition of Miriam’s death and the suddenly renewed water shortage that the rock had yielded its abundant supply of water only thanks to Miriam. When she died, the waters stopped. This traveling rock thus came to be known to some ancient interpreters as “the well of Miriam.” It was Miriam’s virtuous nature, interpreters reasoned, that had caused God to give the Israelites the traveling rock in the first place—a rock went far toward explaining how the Israelites managed to survive all those years in the barren wastes.

Modern scholars have no such recourse to a theoretically mobile rock, however. They note that, while the account of Moses striking the rock at Rephidim occurs in a section of the book of Exodus attributed to either J or E, the similar narrative in Numbers that locates the event at Kadesh is attributed to the source known as P. It would thus appear to scholars that this is another narrative doublet, comparable to the two versions of the flood story, attributed to J and P, or the two accounts of how Jacob’s name came to be changed to Israel, attributed to E and P. Here again, it would seem, a similar story was known to these two different sources, but in slightly different versions—E’s was associated with one geographic location and P’s with another.3 In the final editing of the Pentateuch, scholars say, both versions were allowed to survive; perhaps the fact that one came in the middle of Exodus while the other occurred two books later was enough to allow them to coexist in harmony . . . until the ancient interpreters came along. They were the ones who noticed that the “waters of Meribah” were said to be located in two different places, Rephidim and Kadesh—and then came up with the explanation we have seen.

The Covenant at Mount Sinai

After a period of wandering about, the Israelites at last reached the wilderness of Sinai, the same place where God had first revealed Himself to Moses. (The mountain there is known in the Bible both as Mount Sinai and Mount Horeb.)4 Now God called out to Moses from the mountain once again and told him to transmit to the Israelites a surprising offer:

On the [day that] the third new moon [appeared] after the Israelites had gone out of the land of Egypt—on that very day, they entered the wilderness of Sinai. They had traveled from Rephidim and entered the wilderness of Sinai, camping in the wilderness; Israel camped there in front of the mountain. Then Moses went up to God; and the LORD called to him from the mountain, saying, “Thus you shall say to the house of Jacob, and tell the Israelites: ‘You have seen what I did to the Egyptians, and how I bore you on eagles’ wings and brought you to Myself. Now therefore, if you obey My voice and keep My covenant, you will be My treasured possession from among all peoples—for all the land is Mine. But you shall be for Me a kingdom of priests and a holy nation.’ These are the words that you shall speak to the Israelites.”

Thus begins the event that, in ancient times, was considered by many to be the most important in the whole Hebrew Bible. God’s offer is that, in exchange for Israel agreeing to keep the laws that He is about to give them (that is, “if you obey My voice and keep My covenant”), He will make Israel “My treasured possession from among all peoples.” The point of the observation that follows this promise, “for all the land is Mine,” seems to be that, since this God possesses the entire land, He rules over other peoples as well. But by agreeing to observe the laws that God is about to promulgate, Israel will somehow be singled out from among these other peoples and attain to a unique status: “You shall be for Me a kingdom of priests and a holy nation.”5

What are the laws that Israel has to agree to keep? They start with the Ten Commandments in Exod. 20:1–17 and then continue on into chapters 21–23—dozens of other laws dealing with all manner of things, not only governing relations between God and man (not worshiping other gods, keeping the sabbath, and so forth) but all sorts of civil and criminal legislation: torts, damages, and felonies of various kinds. Indeed, God’s laws do not end with Exodus 23. The next three books—Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy—are themselves packed full of laws, some having to do specifically with priests (kohanim) and the offering of sacrifices, others concerning the people as a whole and their religious obligations, still others touching on matters not normally found in any law code: the prohibition of hating one’s fellow, for example, or the allied injunction to “love your neighbor as yourself.” It would be no exaggeration to say that, from this point in the Pentateuch onward, God’s laws move to front and center; indeed, in a more general sense, the religion outlined in the Pentateuch as a whole is a religion of divine laws. (The point bears emphasis because, as we shall see, nascent Christianity sought—for reasons of its own—to diminish the importance of these laws. The result has been that, in actual Christian teaching and worship, the legal parts of the Pentateuch have often been marginalized or even skipped over entirely.)

A religion of laws might sound like a rather unattractive package. Aren’t most religions about being good, doing the right thing without laws—and, along with this, perhaps, about arriving at some heightened consciousness of God, and of the world as God’s creation?

A fair answer would probably be: no. The truth is, religions vary greatly all over the world (some do not even have anything corresponding to the belief in God), and one people’s religious beliefs and practices often strike other people as superstitious or wrong or absolutely horrible. But the question about the very essence of the above-cited proposal—“Keep My laws and you will become My special people”—is nevertheless an important one to ask, since it highlights not only what is rather unique about the religion of Moses (or, a modern scholar might say, what the Bible presents as the religion of Moses), but how that religion is different from what preceded it. Up until the time of Moses, it will be noticed, God had not spelled out very many demands for Israel to follow (apart from circumcision and a few other matters). There really weren’t any divine laws. At the same time, God’s very presence in the world had been, as we have seen, a rather intermittent and fleeting thing. He spoke to different figures now and again—Noah and Abraham and Jacob and so forth—but then disappeared as if He had never been; indeed, intermittence might be said to be God’s principal characteristic in the book of Genesis.

But now, with God’s offer to the people of Israel at Mount Sinai comes the promise of some steadier, more defined interaction. “You,” God says to Israel, “will be My treasured possession from among all peoples . . . a kingdom of priests and a holy nation.” To understand the second half of this promise, it is essential to know that throughout the ancient Near East, the priests of any given people were the ones who were uniquely privileged to be in touch with their gods. The priests’ job consisted of caring for the god’s house (that is, his temple), offering sacrifices in front of his image, and in general serving him in the place where he was deemed to reside. By saying that Israel would become a kingdom of priests, God seemed to be bypassing this common arrangement. He was saying, in effect: You will all be My intimates—just keep these simple rules that make up My covenant with you.

This may still seem a less unusual idea than it actually was in its original context. It is not only that an established group of professional priests within society seems to have been a staple elsewhere in the ancient Near East; there was also the matter of a covenant consisting of divinely given laws. Gods in the ancient world did not issue laws; men did. Thus we have law codes from earliest times in ancient Mesopotamia—the laws of Ur-Namma of Ur (who ruled from 2112 to 2095 BCE), Lipit-Ishtar (ca. 1930 BCE), Eshnunna (ca. 1770 BCE), Hammurabi (ca. 1750 BCE), and other kings. These ancient codes often begin by mentioning that the gods X and Y established the king on his throne;6 in some cases, the king even claims to be of partially divine ancestry. But the laws themselves are created by the king or his own legists and are thus a matter between human beings. So, for example, if someone in Hammurabi’s kingdom stole a sheep, he committed a crime and had to make restitution to the sheep’s owner (HL ¶8). In ancient Israel, too, he had to make restitution (Exod. 22:1), but he had done much more than commit a crime; he had violated one of God’s laws, that is, he had sinned. By the same token, an ancient Babylonian who obeyed Hammurabi’s laws and never got into trouble was, well, a good citizen. An ancient Israelite who kept God’s laws was more than just a good citizen; he was doing God’s bidding. It is, of course, hard to know how much this difference counted in the minds of ordinary Israelites: a thief is a thief, after all. What is more, the kings of other nations claimed to rule by divine right and sometimes even identified themselves with a god (or, in Egypt, claimed to be divine incarnations themselves); the laws issued in their name thus had some sort of godly backing. Still, there is a categorical difference here, and it is this difference that seems to underlie God’s promise that if Israel keeps His laws it will attain a special, unique status among nations. Indeed, observing all the do’s and don’ts promulgated by God came to be seen, at least at some point in Israel’s history, as a form of divine service—more and more so, in fact, as time went on. This simple fact, as we shall see, determined the whole future of both Judaism and Christianity.

No Other Gods

The very first explicit commandment of the Ten Commandments7 is also one of the strangest: the Israelites are to “have no other gods before [or besides] Me” (Exod. 20:3). Many people mistake this as referring to monotheism, the belief that there is only one God in the world. But that is not what it says. On the contrary, the very formulation “no other gods before [or besides] Me” seems to concede some reality to these other gods: they do exist, and they may even make things happen in the world, but you are not to worship them before, or along with, Me. This view is not what is traditionally called monotheism but monolatry (“worshiping one”), the devotion to a single deity while at the same time accepting the existence of other deities.

When one considers the matter from a distance, monolatry seems an odd practice. After all, different gods and goddesses were usually conceived to exercise different functions in the world—this one was in charge of fertility, that one could bring success in war, a third might preside over the life-giving rains. What good did it do for a whole nation to devote itself exclusively to the worship of the war god, say, when everyone knew full well that drought might strike at any time, necessitating help from the rain god? There is thus something inherently limiting, and ultimately unstable, about monolatry. Where did this commandment come from?

Modern scholars found a possible clue to the answer in the civilization of the ancient Hittites, whose capital, Hattuša (now located in the town of Bogazköy, in north central Turkey), was excavated starting in 1906. In the Late Bronze Age, the Hittites ruled over a vast empire that stretched deep into the territory of present-day Syria, and the library of its capital was found to contain some ten thousand inscribed clay tablets, many of them dealing with international relations and other matters of state. Starting in the 1930s, a number of Hittite treaties were published, and it was not long before these attracted the attention of biblical scholars.8

What interested biblicists in particular was the form these treaties took. As has already been observed, all sorts of documents—business letters, wedding invitations, U.N. resolutions—come to acquire a standard form; the conventions that they obey help readers to identify them immediately and understand their words, both the boilerplate and what is unique in them. So was it with the treaties concluded between the Hittite emperor and his various vassal states. These agreements—conventionally known as suzerain treaties or vassal treaties, since in them the dominant party (suzerain) spells out his demands to the vassal—turn out to have a relatively standardized form. There is, of course, some variety from treaty to treaty, but most of them contain a mixture of the following basic elements:

1. Self-identification of the speaker (that is, the suzerain): “These are the words of the Sun-god [i.e., the king], Mursilis the great king, the king of the Hatti-land, the valiant, the favorite of the storm god, the son of Suppiluliumas, the great king, the king of the Hatti-land, the valiant.”

2. Historical prologue reviewing relations between the suzerain and the vassal: Having thus introduced himself, the king would then proceed to narrate all that he had done for the lowly vassal state. Actually, what the king had usually done was conquer the vassal, but, accentuating the positive, the prologue might instead mention that the great king had installed the present (puppet) ruler of the vassal state on his throne, or the present ruler’s grandfather, and that ever since he had acted justly toward the vassal.9

3. Treaty stipulations: Next came the heart of the matter, the demands imposed on the vassal by the great king. Two concerns were prominent among these: money and loyalty. The first scarcely needs explanation; one of the perquisites of conquering a vassal state was demanding a certain percentage of its gross annual income, payable, it was sometimes stipulated, in pure gold. Loyalty was just as important, however. After all, the very essence of an ancient empire was the radiation of power and influence from one central city or conglomeration of cities outward to more distant cities and towns. The farther these outposts were from the center, the weaker the great king’s influence was likely to be—not only because lines of supply were longer and more difficult, but also because, as one moved farther away from the sphere of influence of one suzerain, one often moved closer to the sphere of influence of a rival suzerain. What was crucial for the suzerain, therefore, was preventing the farthest vassal states in his empire from falling into his rival’s hands. This might, of course, necessitate the stationing of troops on the outskirts of the empire, but the vassal king himself needed to be warned in the strictest terms not to have any secret contact or negotiations with a rival empire. The vassal had to swear absolute loyalty to his suzerain and his allies. As Mursilis put it succinctly with one vassal: “With my friend you shall be a friend, and with my enemy you shall be an enemy.” Further stipulations might involve the obligation to muster troops on behalf of the suzerain, to hand over escaped deportees of the suzerain, to report any seditious speech to the suzerain, and so forth.

4. Provisions for placing the text of the treaty in a public place and for regular public reading: these were necessary lest anyone claim ignorance of the treaty contents.

5. Mention of the gods who acted as witnesses (and guarantors) of the vassal’s acceptance of the treaty.

6. Blessings and curses invoked on those who did, or did not, uphold the treaty’s provisions.

As noted, not all treaties contained all six of these elements, and there were certainly other elements involved in making the treaty official—such as the sacrifice of animals or some ratifying meal or the like—that are not mentioned above. But these are the written essentials.

What captured the attention of biblicists, starting in the 1950s, was the similarity of the form of these treaties to the form of various presentations of God’s covenant with Israel, including, prominently, the narrative of Exodus 19–20 culminating in the proclamation of the Ten Commandments.

The text of the Ten Commandments itself (Exod. 20:1–17; also Deut. 5:6–21) is relatively brief, but it does start off with God’s self-identification (“I am the LORD your God”) and a short allusion to His previous relations with Israel (“who took you out of the land of Egypt, the house of bondage”). It then proceeds to a list of stipulations. The first of these looks strikingly like the suzerain’s demand for exclusive loyalty, “You shall have no other gods before [or besides] Me.” These words, it appeared to scholars, must have carried a definite connotation when they were first uttered: God was approaching the people of Israel like a foreign conqueror and setting out His conditions, the first of which, at least, was altogether standard.

That was not all. Scholars likewise noted that, after listing the rest of the Ten Commandments and the other laws that follow (Exodus 21–23), the text concludes with the typical acts that served to seal a covenant in the human sphere elsewhere in the ancient Near East:

Moses came and told the people all the words of the LORD and all the ordinances; and all the people answered with one voice, and said, “All the words that the LORD has spoken we will do.” And Moses wrote down all the words of the LORD. Then he rose early in the morning and built an altar at the foot of the mountain, and set up twelve pillars, corresponding to the twelve tribes of Israel. He sent young men of the people of Israel, who offered burnt offerings and sacrificed oxen as offerings of well-being to the LORD. Moses took half of the blood and put it in basins, and half of the blood he threw against the altar. Then he took the document of the covenant and read it aloud to the people. They said, “Everything that the LORD has spoken we will do, and we will be obedient.” Then Moses took the blood and threw it over the people, and said, “This is the blood of the covenant that the LORD has made with you in accordance with all these words.”

Then Moses and Aaron, Nadab, and Abihu, and seventy of the elders of Israel went up, and they saw the God of Israel. Under His feet there was something like a pavement of sapphire stone, like the very heavens for brightness. And He did not lay his hand on the chief men of the people of Israel, but they beheld God, and they ate and drank.

To many scholars, this actually looks as if two different ceremonies of conclusion have been edited together. In the first paragraph, the people, who are standing at the foot of the mountain, formally accept the terms of the covenant by saying that they will do everything that God has stipulated. This acceptance is then sealed by the offering of sacrifices and the sprinkling of the sacrificial blood. In the second paragraph, scholars see an alternate ceremony: Moses and the other notables actually go up the mountain to meet the Great King—apparently a dangerous and potentially suicidal act, but one that God permits in this instance; then they “ate and drank” in a covenant-concluding meal, and the deal was completed.

The other characteristic elements of a Hittite treaty—the mention of storing the treaty text in some public place, the list of blessings and curses, and so forth—are not found in the immediate environment of the Ten Commandments, but to scholars the whole atmosphere of an ancient Near Eastern treaty was nonetheless unmistakable. Indeed, it was explicitly presented as such: God Himself, it will be recalled, had said He was proposing a bĕrit, a covenant or solemn agreement, between Himself and the people of Israel (Exod. 19:5). What could be more natural than the use of the standard form and language of a bĕrit, such as might be concluded between human beings? Indeed, elsewhere in the Bible, all of the other elements of the Hittite treaty do appear. Scholars thus pointed to the provision that the Ten Commandments be placed in the Ark of the Covenant (Deut. 10:2), as well as to the lengthy list of blessings and curses that conclude the legal corpora of Leviticus (chapter 26) and Deuteronomy (chapter 28, in addition to the public recitation of curses prescribed in Deut. 27:11–26). What, they asked, could these long lists of curses mean apart from the conventions of an ancient treaty?

Indeed, scholars also saw in the overall form of the book of Deuteronomy something similar to the basic treaty pattern: that book starts with a very lengthy historical introduction reviewing relations between God and Israel (chapters 1–11); then moves to the insistence on exclusive loyalty and, consequently, the avoidance of anything connected with the worship of other gods (chapters 12–13); other laws (14–26); blessings and curses (27–28); provision for public reading of the stipulations (31:9–13); provision for deposit of the text in the Ark of the Covenant (31:24–29).

One more biblical text, Joshua 24, also seemed to combine most of the elements of an ancient treaty. This chapter includes the self-presentation of the suzerain (24:2); a historical prologue (24:2–13); insistence on exclusive loyalty (24:14–21); mention of witnesses (there could be no divine witnesses, of course, so “You are witnesses against yourselves, that you have chosen the LORD to serve Him,” 24:22); and placement of the text at a public site (24:26–27). All these instances, scholars said, could leave little doubt: God’s covenant with Israel followed a standardized treaty form, and his demand of exclusive loyalty, that is, monolatry, was nothing more than the translation into the divine sphere of a demand that any ancient emperor might have made of his vassal.

The Dust Settles

As with many proposed insights of modern scholars, the initial enthusiasm that greeted these ideas was followed by a period of reconsideration and second thoughts. Most of these hesitations concerned the connection of the various treaty elements with, specifically, the Hittites. After all, it was argued, the Hittite empire had essentially gone out of business by the end of the second millennium, even before Israel’s rise as a great nation under David. How could the characteristically Hittite form of treaty have played such an important role in texts dated by many scholars to a much later period? Certainly there were other, later treaties—notably those of various neo-Assyrian emperors, who dominated Israel precisely in the period when, scholars thought, some of the biblical texts involved might actually have been written.10 True, the Assyrian treaties had a somewhat different form—they may have lacked a historical prologue,11 and they certainly had more elaborate demands and penalties—but these, some argued, might actually be more likely than the Hittite treaties to have inspired the biblical models.12 The issue was not merely one of dates but of theology: those who wished to claim that the whole idea of a covenant of divine laws was a relatively late element in the religion of Israel tended to reject the close Hittite comparison.13 Covenant, some said, was a favorite theme of the law code of Deuteronomy (which, as we shall see, they dated to the seventh century BCE—or even later);14 the passages in Exodus 19–24, they argued, must therefore belong to the same period. Other scholars, while not arguing that the traditions reflected in these chapters went all the way back to Hittite times, nonetheless felt that they must be very old. After all, the idea of a divine suzerain concluding a pact with all of Israel, the “nation of priests,” would hardly be conceivable after the time when Israel had an actual king ruling over it; any covenant after that point should presumably be concluded between God and the king.15 Nor would an entrenched priesthood be particularly happy about a text that proclaimed that all Israelites were priests. For these reasons, some scholars argue, the idea of a divine covenant must have been a fundamental of Israelite religion even before the time of David, in the tenth century.16

This is a complicated, ongoing debate and not given to easy summary. Some scholars have pointed to a verse in the eighth-century prophet Hosea as a telling piece of evidence:

Hear the word of the LORD, O people of Israel; for the LORD has a legal case against the inhabitants of the land.

There is no faithfulness or loyalty, and no obedience to God in the land.

False swearing, and murder, and stealing, and adultery break out; bloodshed follows bloodshed.

Therefore the land mourns, and all who live in it languish.

The connection to the Ten Commandments is clear enough; if these are indeed the words of an eighth-century prophet (and most scholars agree that they are), then that would put the Ten Commandments back at least that far—in fact, somewhat earlier, since God here is presented as saying He has a “legal case” (rib) against Israel. In order for Him to indict Israel on these grounds, Israel would have to be presumed to have sworn at some earlier point that it would uphold the provisions that it was now being charged with violating. In other words, Israel’s acceptance of the Ten Commandments would have to have been something of an established fact at the time these words were uttered. (To be sure, this passage does not use the word “covenant” in presenting its charge; perhaps, as some scholars have claimed, this reflects the fact that the theological centrality of the covenant concept emerged only later.17 At the same time, “covenant” does specifically appear later on in the book: see Hos. 8:1.)

This would certainly seem to be a strong point in favor of the antiquity of the Ten Commandments. What is more, however old the actual text of the Ten Commandments might be, the idea that God had established His sovereignty over Israel through the issuance of a set of laws might be still older.18 True, opponents of this idea point to the relative paucity of allusions elsewhere in the Bible to these supposedly early laws. Indeed, it is really only in the books written just before and then after the Babylonian exile of the sixth century, these scholars say, that law itself seems to become a central focus of the religion of Israel. Still (for reasons to be explored in chapter 23), other scholars associate the promulgation of a list of ten simple commandments—the last six of which seem specifically designed to extend kinship obligations to a broader group of unrelated tribes—to the period of Israel’s first emergence as a nation. Only later did these laws come to be conceived as the stipulations of a covenant as such; still later, according to this approach, the original covenant stipulations were modified and augmented by the great set of laws found currently in Exodus 21–23.

Somewhat lost in this debate, however, has been the very conception of God underlying the passages we have been reading. Whether it was influenced more by Hittite or by Assyrian treaty models, the account of God’s conduct with Israel at this point—that is, His sudden appearance as a divine suzerain who announces to this tiny nation His offer of a treaty—seems, on consideration, a very odd way for God to have presented Himself to any group of human beings. What exactly this meant at the time will require further clarification.