Worship on the Road

EXODUS 32 AND LEVITICUS 10, 16, 19, 23

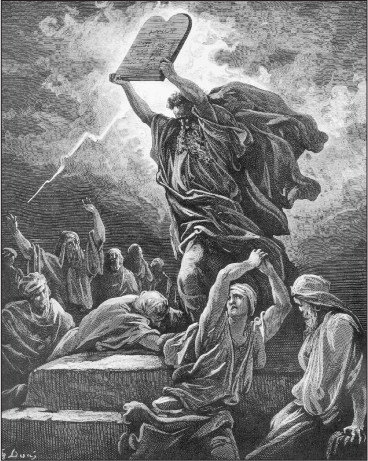

Moses Breaking the Tables of the Law by Gustave Doré.

AARON’S GREAT MISTAKE. ANCIENT NEAR EASTERN TEMPLES. NADAB AND ABIHU. LOVING YOUR NEIGHBOR.

Moses’ brother Aaron was the first priest, the founder of the priestly dynasty. Yet he led the people into their great sin, the worship of the Golden Calf. Did the Bible regard him as a hero or a villain?

Moses stayed on Mount Sinai for forty days and forty nights while God was giving him the laws that went with His covenant. Moses was some eighty years old at the time, and as the period of his absence grew longer and longer, some of the Israelites camped at the foot of the mountain drew the natural conclusion. They thought their old leader must simply have died:

When the people saw that Moses was taking a long time to come down from the mountain, the people reproved Aaron and said to him, “Come, make us some gods to lead us;40 for this fellow Moses, who took us up out of the land of Egypt—no one knows what may have become of him.” Aaron said to them, “Strip off the gold rings that are on the ears of your wives, your sons, and your daughters, and bring them to me.” So all the people stripped off the gold rings from their ears and brought them to Aaron. He took the gold from them, formed it in a mold, and made it into a molten calf. Then they proclaimed, “These are your gods, O Israel, who brought you up out of the land of Egypt!” When Aaron saw this, he built an altar before it; and Aaron announced, “Tomorrow will be a festival to the LORD.” So they rose early the next day and offered burnt offerings and brought sacrifices of well-being. Then the people sat down to eat and drink, and rose up to revel.

This whole incident was extremely troubling. Only three months had passed since God had freed the Israelites from slavery, afflicting the Egyptians in the process with the ten plagues. When the Egyptians nonetheless pursued the departing Israelites, God had miraculously divided the Red Sea, saving the Israelites and drowning their Egyptian pursuers. Nor did the supernatural events cease there: the pillars of cloud and fire, the water drawn from the rock at Rephidim, and the miraculous victory over the Amalekites were soon followed by the great divine revelation at Mount Sinai, when God’s very words were heard by every Israelite man, woman, and child. And now, only a month or so later and with the Ten Commandments still ringing in their ears, the Israelites went and did precisely what those commandments had forbidden, making a molten metal image, the Golden Calf, and bowing down before it. If this were not incredible enough, the Bible even related that Aaron, Moses’ trusted older brother, was the one responsible for this perfidious act.

In considering these events, ancient readers of the Bible assumed some lesson must be intended. But what could it be? That even a righteous man like Aaron can make a mistake? Even if this were true, it was hardly the sort of thing that needed to be communicated to potential sinners, especially since, after Moses returned from the mountain and confronted his brother with his wrongdoing, Aaron seemed only to dodge the blame in the most cowardly fashion, without showing the slightest sign of personal remorse:

Moses said to Aaron, “What did this people do to you to [make you] bring this great sin upon them?” And Aaron said, “Do not let my lord be too angry; you know this people, how they are bent on evil. They said to me, ‘Make us gods to lead us; for this fellow Moses, who took us up out of the land of Egypt—no one knows what may have become of him.’ So I said to them, ‘Whoever has gold, strip it off’; then they gave it to me, and I threw it into the fire, and out came this calf!”

What a lame excuse! What, then, could this story be intended to impart?

As they further considered the matter, interpreters noticed something odd: Aaron’s colleague Hur had disappeared. Just before Moses and Joshua went up the mountain, Moses had left Aaron and Hur in charge, saying to the elders, “Wait here for us, until we come to you again. Aaron and Hur are with you; whoever has a dispute may go to them” (Exod. 24:14). That was the last thing said about Hur in the Bible—when Moses came back down, Aaron was apparently the only one in charge. Of course, Hur might have died in the interim. But surely the death of such a leader of Israel, the one who, together with Aaron, had supported Moses’ tired arms at Rephidim, would not have passed without mention. The more interpreters thought about it, the more it seemed that Hur’s sudden absence was one of those little hints that the Torah dropped from time to time, preferring to relate by indirection events that were too troubling to narrate openly. So it was that interpreters came to the conclusion that Hur had indeed died, but not as a result of natural causes.

A righteous man and a responsible leader, he must have been against the whole Golden Calf project from the start, publicly opposing it and urging Aaron in the strongest terms not to cooperate. If so, then what was an enraged mob likely to have done? Hur’s unexplained disappearance must represent the Bible’s delicate way of pointing to an ugly truth: the mob rose up against Hur and killed him for his opposition to the Golden Calf. Then Aaron, fearing that any further provocation might put his own life in danger (and so bring down yet another sin on the people of Israel), reluctantly complied with their wishes:

When the people of Israel started to do that deed [of the Golden Calf], they first went to Hur and said to him, “Come make a god for us.”1 When he did not do as they said, they went and killed him . . . Afterward they went to Aaron and said to him, “Come, you make us a god.” When Aaron heard he took fright, as it is said, “And Aaron was afraid and he built an altar in front of it” [variant reading of Exod. 32:5].

Leviticus Rabba 10:3

Seen in this light, Aaron’s action seemed not only reasonable, but almost heroic. Wishing to spare the Israelites further sin, he cooperated with their plan; then, when Moses came down from the mountain, Aaron told him nothing of Hur’s murder and the Israelites’ threats against him, instead pretending that no one was really responsible: “I threw it into the fire, and out came this calf!” Indeed, Aaron’s willingness to preserve harmony at almost any cost may have contributed to his postbiblical reputation as a peacemaker:

Hillel said: “Be of the disciples of Aaron, loving peace and pursuing peace, loving other people and leading them to the Torah.”

m. Abot 1:12

Broken Tablets

Moses was of a somewhat less irenic constitution. When he learned what the Israelites had done, he took the two stone tablets that he had carried down from the mountain, tablets that had been inscribed by God’s own hand, and threw them to the ground, shattering them to bits. (Ever after, these bits of broken stone were preserved in the sacred Ark of the Covenant, a precious memorial.)

In breaking God’s own handiwork, it seemed as if Moses might have gone too far, giving in to the emotion of the moment—though interpreters labored to find some explanation for his act.2 In any event, after the Golden Calf incident, Moses and his fellow Levites also killed three thousand of the sinners, and God further afflicted the Israelites with a plague (Exod. 32:25–35). God then announced that He would be sending Moses and the Israelites off to Canaan alone. They were too sinful for God Himself to accompany them—He would remain at Mount Sinai and send along an angel instead (Exod. 33:1–3).

But Moses went again to intercede with God, and presently He agreed to accompany the Israelites into Canaan: “I will do the very thing that you have asked; for you have found favor in my sight, and I know you by name” (Exod. 33:17). God then told Moses to make a new pair of stone tablets so that He might write out the commandments once again. Moses did so and went back up Mount Sinai, once again asking God to forgive His people’s sinfulness. What Moses received was more than he had asked for. God revealed to him His own essence: He is a God who is not indifferent, but fundamentally kind and merciful:

Moses carved out two stone tablets like the first ones and rose early in the morning to go up on Mount Sinai as the LORD had commanded him, taking the two stone tablets in his hand. Then the LORD came down in a cloud and stood with him there, and proclaimed the name “LORD.” [That is,] the LORD passed before him and proclaimed, “The LORD, the LORD, a God merciful and compassionate, slow to anger, and abounding in kindness and faithfulness, extending kindness to the thousandth generation, forgiving iniquity and transgression and sin; yet He does not give up punishment completely, but [sometimes] visits the iniquity of the parents upon the children and the children’s children, to the third and the fourth generation.” Then Moses quickly dropped to the ground and bowed low.3

Temples and the Gods

The incident of the Golden Calf was a horrible apostasy. Ironically, the narration of those events is sandwiched in the midst of God’s instructions to Moses concerning the building of a special structure, the tabernacle, which was to serve as a kind of mobile temple or sanctuary during the Israelites’ desert wanderings on their way to Canaan.

What was the purpose of such a mobile temple? Scholars have learned a great deal about temples in the ancient Near East over the past century. One thing is clear: the temple was not (as the word might seem to indicate to many people today) principally a place where the faithful assembled to pray or read Scripture. This is the main purpose of a synagogue or church, but not of an ancient temple. A temple in the ancient Near East was essentially the house of the deity. The god or goddess was actually deemed to take up residence inside the temple. Temples were therefore lavishly appointed, so as to provide truly royal surroundings in which the deity might abide in splendor. This same general conception of the temple is reflected in God’s instructions to the Israelites to build the tabernacle:

The LORD said to Moses: Tell the Israelites to bring Me an offering; from everyone whose heart so moves him shall you receive the offering for Me. This is the offering that you shall receive from them: gold, silver, and copper; blue dye and purple, with crimson yarns, fine linen, and goats’ hair; tanned rams’ skins, fine leather, and acacia wood; oil for lighting, spices for the anointing oil and for the fragrant incense; onyx stones and gems to be set in the ephod and for the breast-piece. And have them make Me a sanctuary, so that I may dwell among them. Exactly as I shall show you—the plan of the tabernacle and of all its furnishings—so you shall make it.

Of course, in the ancient Near East, the deity was not thought to exist just in that one place: he or she might also be somewhere else in the natural world or in the sky, or simultaneously in another temple (though how this was done was not explained). But the presence of the deity inside the temple meant that there would always be a spot within human reach where the deity could be approached and served, where people might go to offer gifts that would bring favor on them or to present their heartfelt requests for help.

Temples in the ancient Near East were a very, very old institution. The oldest surviving Mesopotamian remains of temples go back to the early fifth millennium BCE—long before there were written records of any kind—but it is quite likely that temples existed even before then, perhaps built out of perishable materials that have left no trace. As with any very ancient institution, trying to understand the place of temples and gods in the life of ordinary people is no simple task; once such an institution is established, most people soon stop speculating about why it exists or how it works. So is it also, for example, with prayer nowadays. Many Jews and Christians and Muslims pray to God regularly. But how many of them think consciously about what occurs when they pray? Does God “hear” them wherever they are—and can He hear and respond to millions of prayers simultaneously? Is it enough merely to think a prayer for God to hear it, or does a person actually have to whisper the words or speak them aloud? Is a prayer spoken by a hundred people simultaneously more likely to be answered than one spoken by a single individual? Different answers have been offered to all these questions by philosophers and theologians, but for the most part, ordinary people just don’t think about them: prayer simply exists, it is how one speaks to God—the mechanics are not that important (and perhaps unknowable).

So was it with temples in the ancient Near East. They had always been there and, as far as anyone knew, always would be. The temple was where the god lived, in a special niche, embodied in a spindly little statue of wood overlaid with precious metals and cloth. The statue was not a representation of the god; the god was believed to have actually entered its wood and metal or stone, so that now this was the god—he was actually right over there.4 “Go before Enki,” people would say, or, “Offer this to Marduk.” The statue may have been small, but the god inside it radiated power. After all, the gods controlled all that was beyond human controlling, and humans fell before them in abject deference. People invoked the gods, implored the gods, named their own children after gods (“Marduk-Have-Mercy-on-Me,” “Ishtar-Is-Heaven’s-Queen,” “Guard-Me-Shamash”), and even when people were not consciously thinking about the gods, they nonetheless lived every minute of their lives in the gods’ shadow.

Animal Sacrifices

Inside the temple was a special coterie of the god’s servants. These were the priests, who in many ways were comparable to the slaves or household staff of a high official or king. Their job was to do all that was possible to insure that the god was properly served and so was able to look to the prosperity and success of the city in which his temple stood. This involved, among other things, offering animal sacrifices to the god—and this, like the idea of the temple itself and the divine statues, is so far from the experience of most of us that it requires a willful act of imagination to recapture its essence.

Why did peoples of the ancient Near East (and elsewhere) pile the altars of their gods with the still-warm carcasses of sheep or bulls? Ancient texts themselves offer a host of explanations: this was the deity’s food (indeed, in the Bible itself God refers to “My sacrifice, the food of My offerings by fire” [Num. 28:2]); the life of the slaughtered animal was offered as a substitute for the offerer’s life (that is, “better it than me”); the animal was a costly possession given up as a sign of fealty or in the hope of receiving still more generous compensation from the deity.5 To these traditional explanations have been added more recent ones that see the sacrifice as establishing a tangible connection between the sacrificer and the deity.6 Others have sought to stress the connection of the sacred with violence or see the function of religion overall as defusing violence that would otherwise be directed at other human beings.7

Even if it were possible to recapture the original idea behind animal sacrifices—and it isn’t—the search for such an original idea can tell us little about the function of sacrifices in Israel during the biblical period (or in any other ancient society). As one scholar has recently argued, that would be like trying to understand the meaning of a word by searching for its etymology: the word “silly” is an adjective originally derived from sele, a Middle English noun that meant happiness or bliss, and “silly” itself used to mean “spiritually blessed” or even “holy”—but that does not mean that the word nowadays has any such associations in the minds of English speakers. Similarly, the function of sacrifice—or any ritual act—cannot be understood by trying to reconstruct the original circumstances that gave rise to it.8

Moreover, such thinking betrays a fundamental misunderstanding of religious ritual. The ritual act itself is what is important, not its symbolism or purported meaning. To a certain way of thinking, ritual does something. (As the American writer Flannery O’Connor, a devout Roman Catholic, once said about the Eucharist: “If it’s a symbol, the hell with it.”)9 Animal sacrifices in Israel were conceived to be the principal channel of communication between the people and God. In prayers, of course, people spoke to God, but for all that, prayer was not primary. The sacrifice—the passage of a small, palpable, breathing animal from life to death and from the world of the living upward through the flickering flames of the altar—spoke louder than any prayer. As Platonis Sallustius, a fourth-century philosopher and author of On the Gods and the World, observed, “Prayer without sacrifice is just words.”10

Such was worship in biblical Israel and elsewhere in the ancient Near East. It is to be stressed that the temple itself was a world apart; the house in which the god lived was not conceived to be continuous with the world outside. It was separate, sealed off; and it radiated holiness. One interesting piece of testimony to this fact is the temple recently excavated at ‘Ein Dara‘, in modern Syria.11 The temple resembles others excavated from that part of the world (as well, incidentally, as Solomon’s temple, according to its biblical description)—save for one striking feature. On the steps leading up to this temple’s doorway, the builders carved a set of huge footprints, symbolically representing the god’s entrance into his sanctuary. The footprints are sunk into the temple steps in the same way that human footprints might be sunk into mud or wet concrete—but the feet themselves are many times bigger than human feet, and the length of the stride they mark off is far greater than a human’s stride. Archaeologists estimate that, on the basis of this stride, the god or goddess of that temple would have to have been some sixty-five feet tall! How could such a huge deity ever make its way through the rather normal-sized entrance of the temple? This, apparently, did not trouble the temple’s otherwise careful planners. Why not? Because they knew that the inside of this temple, of every temple, was a world apart, a little condensed, time-stopped bit of eternity that was discontinuous with the everyday world that surrounded it, a world in which a spindly little statue could indeed be the same god that stood sixty-five feet high on the outside.

The Tabernacle and Modern Scholarship

Modern scholars note that the religion of Israel was a relatively late development in the ancient Near East. Long, long before there had even been an Israel, the gods had been worshiped in temples that dotted the landscape of ancient Canaan and environs. Israel’s own religion ended up being, in some respects, strikingly different from those of its neighbors; but modern scholars are equally attuned to the similarities. Thus, Solomon’s temple as described in the book of Kings seems to have a floor plan altogether typical of West Semitic temples such as the ones excavated at ‘Ein Dara‘ or Tel Ta‘yinat in Syria; the different classes of sacrifices offered in Israelite temples used some of the same names found in ancient Canaanite texts; the priests were designated by the same word; and so forth. Indeed, even Israel’s way of referring to its God parallels phrases and appellations used for Canaanite gods in texts discovered in northern Syria.

It is therefore not surprising that, like Solomon’s temple, which eventually replaced it, the desert tabernacle that God commanded the Israelites to build (Exodus 25–27) should—in its dimensions, appurtenances, and the sacrifices that were to be offered within its precincts—resemble the sanctuaries found at neighboring sites in the ancient Near East and the worship conducted within them. About this tabernacle, however, modern scholarly opinion continues to fluctuate. To Julius Wellhausen and other late-nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century scholars, it seemed obvious that the tabernacle was simply a literary fiction. There never was a tabernacle. Long after the people of Israel had emerged—indeed, long after it had been decided that, instead of multiple holy sites dotting the landscape, there was to be a single, centralized temple in Jerusalem—some priest or scribe, in seeking to imagine the Israelites’ desert wanderings after the exodus from Egypt, naturally supposed that they too had had a central shrine. But how could they if they were wandering all the time? It must have been a portable shrine, he supposed, a tent that could be packed up and moved from place to place. Thus was created, according to Wellhausen and others, yet another biblical fiction: the whole account of the desert tabernacle was a wholesale retrojection of the much later reality of temple worship in Judah.

More recently, some scholars have taken issue with this view. In particular, F. M. Cross has suggested that the whole idea of a tent shrine is actually borrowed from an ancient Canaanite notion, according to which the supreme god El dwells in a tent; the Israelite cherubim throne, the planks (qerashim), and other appurtenances, Cross and others have argued, are likewise borrowed motifs attested in the ancient writings of Ugarit.12 This may not necessarily authenticate the biblical picture of a portable shrine, but it certainly could make the idea of such a shrine far older than Wellhausen supposed. Similarly, other scholars have suggested that, while such a tent shrine may not go back to the period of desert wanderings, the idea may have been based on an actual tent shrine in David’s day or possibly on a tent sanctuary at Shiloh; its dimensions, others have noted, seem to match those of an ancient temple unearthed at Arad.13

When it comes to the actual details of how the Israelites built the desert tabernacle, most modern readers feel their eyes closing. The instructions given by God (Exodus 25–31) are themselves somewhat repetitious, and the account of these instructions subsequently being carried out (chapters 35–40) is, for pages and pages, virtually a verbatim recapitulation of the instructions themselves. Why all this verbiage, when the whole thing could have been summed up in a sentence or two? But for ancient Israelites, the tabernacle itself was highly significant, and the detailed account of its construction must have held a certain fascination. Here were the precise specifications of the structure that allowed God to take up residence once again in the midst of humankind—the first time He had done so since the Garden of Eden.

A Mysterious Death

With the tabernacle complete, the Bible next turns to what is supposed to go on inside it—laws governing the offering of different kinds of sacrifices and what the priests are to do to prepare them. All this occupies the first seven chapters of the book of Leviticus. (The book’s name, incidentally, derives from the fact that priests and other temple officials were all said to descend from a single tribe, Levi.) Once those instructions have been imparted, the Israelites can begin their sacrificial worship of God. The tabernacle is made ready and anointed; the priests—Aaron and his sons—are given their special priestly vestments and consecrated; and then . . . the unthinkable happens.

Now Aaron’s sons, Nadab and Abihu, each took his censer, put fire in it, and laid incense on it; and they offered unholy fire before the LORD, such as He had not commanded them. And fire came out from the presence of the LORD and consumed them, and they died before the LORD. Then Moses said to Aaron, “This is what the LORD meant when He said, ‘Through those who are near Me I will be kept holy, and [thus] by all the people I will be honored.’” And Aaron was silent.

On what ought to have been one of the happiest days in Israel’s history—the inauguration of the tabernacle service—two of Aaron’s sons slip up somehow in priestly procedure and immediately die as a result. But was God really so severe as to kill two novices simply because they made a mistake on their first day on the job?

The text did offer some clues as to what went wrong. To begin with, Nadab and Abihu are said to have brought “unholy fire” right before God. The word “unholy” here (zarah) actually means something closer to “foreign” or “strange,” but in the context of the tabernacle, it designates anyone or anything that is not authorized to be there (see Num. 1:51; 3:10, 38; 18:7). Apparently, Aaron’s sons had willfully used incense coals from somewhere outside of the sanctuary—a grave infraction. Perhaps, too, that was the sense of God’s words cited by Moses immediately following the incident, “Through those who are near Me I will be kept holy, and [thus] by all the people I will be honored.”14 Those who are near Me are the priests, the ones who get to enter directly before the place of God’s presence. These words might thus be reworded more directly as: “Only if you priests respect My holiness will I be honored by the rest of the people, so don’t take liberties or get sloppy.” Perhaps it was important that this matter be straightened out on the tabernacle’s very first day—even if it did mean the death of two of Aaron’s sons.

On the other hand, immediately following the incident came a divine instruction that offered another clue:

And the LORD spoke to Aaron: Drink no wine or strong drink, neither you nor your sons, when you enter the tent of meeting, lest you die; it is a statute forever throughout your generations. You are to distinguish between the holy and the ordinary, and between the unclean and the clean; and you are to teach the people of Israel all the statutes that the LORD has spoken to them through Moses.

If, following his sons’ death, the first thing that Aaron is told is, “Drink no wine or strong drink, neither you nor your sons, when you enter the tent of meeting, lest you die,” then it would seem that the cause of their death might well have been drunkenness. Indeed, this may have been the full story behind the incident: Nadab and Abihu had become intoxicated, and that is what led them to bring the “unholy fire” into the sanctuary. Drunkenness might indeed cause a person to fail to (in God’s words just cited) “distinguish between the holy and the ordinary, and between the unclean and the clean.” If so, this certainly was a grave error. After all, distinguishing between the holy and the ordinary is precisely what being a priest is all about, as Moses had intended to say in citing God’s words “Through those who are near Me I will be kept holy, and [thus] by all the people I will be honored.” It was a hard lesson to have to learn on the sanctuary’s first day, but one that would forever echo in the ears of the temple staff.15

The Holy People

While much of Leviticus is thus taken up with priestly matters, there are nonetheless more than a few items that pertain to all of Israel. Particularly striking is a large section of instructions from Leviticus 17–26, whose main theme is that of holiness. For that reason, these chapters are known to scholars as the Holiness Code.16

What exactly does “holiness” mean? The Bible never defines it. Perhaps the reason is that no definition was necessary. Holy just is; it is an unmistakable state of being. In biblical Israel, this adjective belongs, first and foremost, to God: He is holy beyond any other trait. The seraphim who praise Him in heaven have, according to Isaiah, only one thing to say about Him: “Holy, holy, holy is the Lord of Hosts.” He is, time and again, “Israel’s Holy One.” Holy is that which most characterizes God.17

God’s holiness rubs off, however, on whatever is close to Him or belongs to Him. Thus heaven is His “holy dwelling” and the earthly tabernacle or temple in which He dwells is likewise the “holy place,” or even “the holy place of holiness” (miqdash ha-qodesh). Indeed, the place inside it set off for Him is called the “most holy place” (literally, the “holy of holies”). The furnishings of the sanctuary are also holy, as are the priests who serve before Him and the sacrifices that they offer. The day that God set aside for rest—God’s day, as it were—is also holy (Exod. 16:23; 20:8; 31:14–15; 35:2; Deut. 5:12; Isa. 58:13–14, etc.). The fact that Israel is the people chosen by God to receive His covenant makes them holy too; they are to be, according to the formulation already seen, a “kingdom of priests and a holy nation” (Exod. 19:6). It thus seems that God’s holiness is not only His salient characteristic, but one that radiates out and sticks in various degrees to everything that is His or is near Him.

The surprising thing about the laws of Leviticus 17–26 is the extent to which Israel’s holiness is stressed there. Repeatedly the text urges people to be holy: “Act holy and be holy; for I am the LORD. Keep My statutes and observe them; I the LORD have made you holy” (Lev. 20:8). But what does it mean to be commanded to be holy?

If the laws accompanying this exhortation are any guide, being holy involves things connected with sacrifices and the tabernacle and ritual purity (which was maintained by keeping oneself from eating unclean animals and from forbidden sexual relations, contact with dead bodies, and so forth); but it also includes certain moral and ethical strictures. To put it another way: the Holiness Code brings together the “vertical” and “horizontal” dimensions of religion, matters between humans and God on the one hand and matters that are between humans and their fellow creatures on the other.18 These two types of laws are lumped together in a way that can only seem intentional—as if the Bible were saying, “Your being holy involves this as much as that.” Thus, for example:

The LORD spoke to Moses, saying: Speak to all the congregation of the people of Israel and say to them: You shall be holy, for I the LORD your God am holy. You shall each respect your mother and father, and you shall keep My sabbaths: I am the LORD your God. Do not turn to idols or make cast images for yourselves: I am the LORD your God.

When you offer a sacrifice of well-being to the LORD, offer it in such a way that reflects well on you. It shall be eaten on the same day you offer it, or on the next day; and anything left over until the third day shall be consumed in fire. If it is eaten on the third day, this is a perversion; it cannot be accepted. All who eat it shall be subject to punishment, because they have profaned what is holy to the LORD; and any such person shall be cut off from the people.

When you reap the harvest of your land, you shall not reap to the very edges of your field, or gather the gleanings of your harvest. You shall not strip your vineyard bare, or gather the fallen grapes of your vineyard; you shall leave them for the poor and the alien: I am the LORD your God.

You shall not steal; you shall not deal deceitfully or falsely with one another. And you shall not swear falsely by My name, profaning the name of your God: I am the LORD.

You shall not defraud your neighbor; you shall not rob; and you shall not keep for yourself the wages of a laborer until morning. You shall not curse the deaf or put a stumbling block before the blind; you shall fear your God: I am the LORD.

This assemblage begins with the exhortation to “respect your mother and father”—certainly an interhuman concern. But then in the next breath it commands people to keep the sabbath, a matter between man and God. In the latter category as well are the next matters treated, avoiding idol worship and acting properly with regard to sacrifices. But then come more interhuman matters: Always leave a little of your grain harvest behind in the fields, the text says, so that poor people and foreigners can glean some of it for themselves. The same goes for your vineyard. Outlawed as well are shady business practices: “You shall not steal; you shall not deal deceitfully or falsely with one another.” It is even forbidden to withhold a day laborer’s wages until the next day: payment must be made that very day. All this, the text says, is part of being holy.

A great many of these laws are completely unenforceable. After all, what is involved in “respecting” your mother and father—and who is going to determine that you have violated such a stricture? If I leave behind a single stalk of wheat in the corner of my field, will I be deemed to have kept the requirement of leaving some food for the gleaners? Probably not. But then, how much is enough? The Bible doesn’t say. How about avoiding deceitful business practices—am I still allowed to “forget” exactly how old is the horse I’ve brought to market, and can I imply, without quite saying so, that the house I’m selling has never had any structural problems? Since none of these things is spelled out, what actually violates the law is always going to be a matter of opinion. That is perhaps true most of all of the last commandment, “You shall fear your God.” “Fear of God” in biblical Hebrew actually has nothing to do with God directly; this is an old idiom meaning something like “common decency” in English.19 How can you order someone to have common decency? That seems to be the reason why the text keeps coming back to its main point, being holy. “You know what it means to be holy,” it seems to say. “So there is no reason to try to specify everything involved. Just don’t do anything that is not appropriate to someone who is holy.”

Loving Your Neighbor

Precisely because they seemed to cover so much—and to cover things that no other law code would ever dare include, dependent as they are on the individual’s own heart and judgment—these laws drew the attention of the ancient interpreters, whose job, after all, was to determine exactly how biblical laws were to be applied to daily life. Particularly significant for them was the series of brief laws that appears somewhat later in this same chapter:

You shall not hate your brother in your heart; you shall reprove your neighbor, and you shall incur no guilt because of him. You shall not take revenge or bear a grudge against any of your people, but you shall love your neighbor as yourself: I am the LORD.

Lev. 19:17–18

Hatred “in the heart,” interpreters concluded, was hidden hatred, resentment that simmered inside a person but never expressed itself openly. (It was “in the heart” but not in the mouth.) The antidote to such hatred they found in the next clause, “You shall reprove your neighbor.” That is, if A finds out that B has insulted him behind his back, B must not simply be quiet about it. He should go right up to A and reprove him, “I heard what you said and I don’t like it one bit.” Here is how one ancient interpreter, Ben Sira, explained this law in the early second century BCE:

Reprove a friend so that he not do it—and if he did, that he not do it again.20

Reprove a neighbor so that he not say it—and if he did, that he not repeat it.

Reprove a friend, since often it [what you heard] is slander—so don’t believe everything [you hear].

It also happens that someone errs without meaning to—and who has not sinned with his speech?

Reprove your friend before you grow angry—and give place to the Almighty’s Torah.

Ben Sira’s account is sensitive to the ways (and wiles) of the human heart. Even if the harm has already been done, he says, it is always worthwhile for you to reprove the offender, at least to prevent a repetition. And who knows? Perhaps the whole thing will turn out to have been untrue, the invention of someone who wanted to stir up trouble between you and B. Even if it is true, Ben Sira suggests, perhaps B did not mean it; only by openly confronting the offender will such things come out. Finally, if B proves to have intended every word, the reproof will at least serve to defuse the situation “before you grow angry.” After all, there are legal remedies for such offenses, so “give place to the Almighty’s Torah.”

The next verse went on to forbid revenge and bearing a grudge—and to this too ancient interpreters gave a down-to-earth application in everyday life.41 But what about the very last part of this passage, the commandment to “love your neighbor as yourself”? These words were both an inspiration and a puzzle.21 Did they mean that if, for example, I win a million dollars in the lottery, I have to distribute half that sum to my neighbor? Or, if my life and my neighbor’s are both in danger, is the Bible telling me that I cannot give my own life preference? This seemed like a tall order, virtually inhuman—but some ancient interpreters nonetheless took that route:

Be loving of your brothers as a man loves himself, with each man seeking for his brother what is good for him, and acting in concert on the earth, and loving each other as themselves.

Jubilees 36:4

You shall not hate any man, but some you shall reprove, others you shall pray for, and others you shall love more than your own life.22

Didache 2:7

You shall love your neighbor even above your own soul [life].

Letter of Barnabas 19:5

To other ancient interpreters, however, the Bible seemed to be saying something rather different. To love your neighbor “as yourself” did not mean to love him as much as yourself, but rather as you would wish him to love you. (Technically speaking, this interpretation takes “yourself” as the direct object not of your loving, but of his: “You shall love your neighbor as [he should love] yourself.”) Thus:

The way of life is this: First, you shall love the Lord your Maker, and secondly, your neighbor as yourself. And whatever you do not want to be done to you, you shall not do to anyone else.23

Didache 3:1–2

Do not take revenge and do not hold on to hatred, and love your neighbor; for what is hateful to you yourself, do not do it him; I am the LORD.

Targum Pseudo-Jonathan Lev. 19:18

As such, this one commandment seemed to sum up everything the Torah had to say about the “horizontal” dimension of biblical law, interhuman relations.24 It was often cited in precisely this sense:

But among the vast number of particular truths and principles studied, two, one might almost say, stand out higher than all the rest, that of [relating] to God through piety and holiness, and that of [relating] to fellow men through a love of mankind and of righteousness.

Philo, Special Laws 2:63

The commandments are summed up in this one sentence, “You shall love your neighbor as yourself.”

“And you shall love your neighbor as yourself”—R. Akiba said: This is the great general principle in the Torah.

Sifra Qedoshim 4

In short, while much of Leviticus was taken up with technical matters connected to the tabernacle (sacrifices, laws of purity and impurity), the great section of laws that began in chapter 19 seemed to strike a different note. Here God told His people that their unique status as a “holy nation” imposed on them duties well beyond anything any human legislator might impose. Being holy meant always trying to do the right thing, to walk about in the halo of purity that befits those chosen to receive God’s commandments.