Moses’ Last Words

NUMBERS 22–24 AND

DEUTERONOMY 5:6–21; 6:4–9; 27–28; 32–34

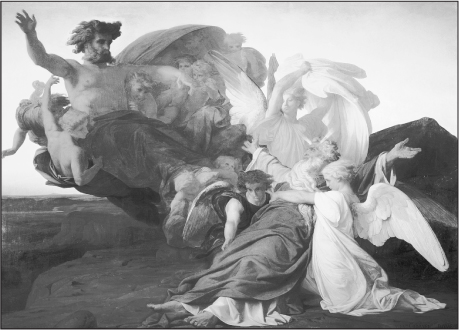

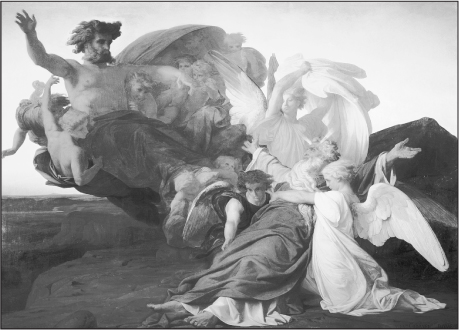

The Death of Moses, 1851 (oil on canvas) by Alexandre Cabanel (1823–89).

A PROPHET FOR SALE. “HEAR, O ISRAEL!” GUARDING THE SABBATH. ISRAEL’S LAST WARNINGS. ESARHADDON AND THE LOVE OF GOD. DEATH OF MOSES.

The Israelites wandered the desert for forty years. Finally, as they approached Canaan, Moses gave them their final instructions. He himself was not to enter Canaan, however; God had ordered him to die on the brink of his mission’s completion.

After Korah’s rebellion, the people continued on their slow march to Canaan. They tried at first to enter via Edom, to the southeast of their future homeland, but the Edomites refused them passage (Num. 20:18). So they turned north instead and ultimately circled around Edom, scoring victories on the way over the Amorite king, Sihon, and Og, king of Bashan. Soon they were on the doorstep of Moab, directly east of Canaan. It was then that the famous confrontation with Balaam occurred. It happened like this:

The Moabite king, Balak, was clearly worried at the progress of this new people in the region. He therefore appealed to a renowned soothsayer, Balaam son of Beor, to help rid him of the Israelites. Balaam had a reputation as a curser, someone who was capable of harming people through his imprecations. Balak therefore offered Balaam a hefty sum to travel from Aram to Moab and curse the Israelites, and after some hesitation, Balaam agreed. Before his departure, however, Balaam received a divine warning: “Do only what I tell you to do” (Num. 22:20).

On his way to Moab, Balaam ran into the snag: his donkey, spotting an angel in front of them, shied from the road and ran into a nearby field, refusing to budge. Balaam at first saw nothing and, furious at his donkey, beat the poor animal mercilessly. It was only when she protested (actually speaking to her master in human words) that he finally spotted the angel himself and understood why she would not move. The angel then told Balaam that he could continue his journey but cautioned him again in God’s name: “You can say nothing other than what I [God] tell you” (Num. 22:35).

Arrived in Moab, Balaam tried to cooperate with the king’s wishes. But every time he opened his mouth to curse Israel, all that came out were blessings. Some of them were worded in the elegant language of biblical poetry:

From the top of these crags I see them, as I gaze from the mountain heights:

A people that dwells apart and is not reckoned among the nations!

Who can count the dust of Jacob, or number Israel’s dust-clouds?

Let me die the death of the righteous47 that my offspring may be like him!

How lovely are your tents, O Jacob; O Israel, your encampments!

Like softly swaying palm groves, or gardens beside a river,

Like aloes the LORD has planted, and cedars on watery banks.

Water shall flow from his buckets, and his seed shall have mighty streams.

A star will come forth from Jacob, and from Israel rise up a scepter.

It will crush the Moabites’ brow, and the forehead of all of Seth.

Edom will be its possession, and Seir will fall to its spoil:

Yes, Israel will triumph!

Needless to say, these words did not find favor with Balaam’s employer, King Balak. He dismissed Balaam without the promised emolument, and the professional curser returned to his homeland.

One would think, given this bare recital, that Balaam would have been one of Israel’s cherished heroes, a foreign soothsayer who blessed Israel instead of cursing. But his reputation among ancient interpreters was quite the opposite: he was Balaam the Wicked. Part of the reason lay in the story itself. After all, he tried to curse Israel; it was only that God would not let him. More than that, however, was the role that money played in the story. When Balak’s envoys approached Balaam with their offer, they said in the king’s name: “I will surely do you great honor, and whatever you say to me I will do; come, curse this people for me” (Num. 22:17). Much of this was diplomatic code language. “Great honor” is an elegant way of saying “a lot of money,” and “whatever you say to me I will do” meant: name your price. Balaam took the hint, replying, “Even if Balak were to give me his palace full of silver and gold, I could not go beyond the command of the LORD my God.” Nice words—but what they really meant, interpreters felt, was, “This could really cost you.”

Woe to them [ungodly men]! For they . . . abandon themselves to Balaam’s error for the sake of gain.

Whence do we know that Balaam had a large appetite [for money]? From his saying, “Even if Balak were to give me his whole palace full of silver and gold, I could not go beyond the command of the LORD my God.” [That is, he would not have mentioned silver or gold if that were not what was really on his mind.]

Abot deR. Natan (B) ch. 45

At first he was a holy man and a prophet of God, but afterward, through disobedience and the desire for lucre, when he tried to curse Israel, he was called by the Holy Writ a “soothsayer” [Josh. 13:22].

Jerome, Questions in Genesis 22:22

In short, Balaam the Wicked was one of the great villains of the Hebrew Bible, taking his place next to the diabolical fratricidal Cain and the seditious Korah in the rogues’ gallery of ancient Israel. “Don’t be like these,” Scripture was saying.

Balaam and Modern Scholarship

In 1967, an Arab worker at an excavation site at Deir ‘Alla‘, in Jordan, discovered a piece of plaster with writing on it. It turned out to be part of an inscription dating back deep into biblical times, perhaps belonging to the late eighth or early seventh century BCE.1 It was written in a dialect that seemed to be some sort of mixture of Aramaic and Hebrew. The inscription was full of lacunae, but it clearly reported on someone named Balaam son of Beor,

who was a seer of the gods. The gods came to him in the night, and he saw a vision like an oracle of [the god] El. Then they said to [Balaa]m son of Beor: Thus he will do [ ] hereafter, which [ ]. And Balaam arose the next day . . .2

The inscription went on to tell a (very fragmentary) story different from the one in the Bible, but it nevertheless delivered a shock to scholars. After all, there could hardly be a story in the Bible that seemed more fictional than Balaam’s—a professional curser and his talking donkey! Yet here was a certifiably ancient inscription that spoke of precisely such a man, and described him just the way the Bible did, as a seer who communicated with the divine at night. Indeed, the fact that the inscription spoke of “the gods” in the plural and named the Canaanite god El in particular only added to its historical cachet: apparently such a man, or at least the legend of such a man, existed outside of the biblical orbit. In the Bible, Balaam obeys “the LORD,” but in the inscription he belonged to the world of those who still spoke of “the gods” and El. Did this mean that behind the biblical narrative stood some real, historical figure?3

This point of contact between the Bible and an excavated text has not, however, stopped scholars from asking the usual questions about the biblical story as it now exists: Is it all of one piece? Why was it written? And by whom? On all these questions opinion is still somewhat divided.4 One thing on which most scholars agree, however, is the episode of Balaam and the talking donkey: they believe that this is an insertion into an earlier story. The reason is that this episode seems intended to portray Balaam in a negative light: the great seer cannot even perceive what his donkey can! Take that incident out, scholars say, and you have a smoothly running narrative that presents Balaam altogether positively, as someone who, from the beginning, knew that Israel was blessed by God (Num. 22:12). Although he went to Moab as Balak requested, Balaam nevertheless warned the king time and again that he could say only what God allowed (Num. 22:38; 23:12, 26; 24:12).

The fact that, without the donkey incident, the story portrays Balaam altogether positively does not mean, however, that this positive portrayal is itself all the work of a single author. After all, scholars note, the prose framework seems at variance with the blessings spoken by Balaam in some of its details.5 Moreover, because of their language and orthography (spelling), the blessings appear to be quite ancient. Albright in particular highlighted some of their archaic features.6 But even the blessings may not be of one piece. One theory holds that the first two blessings (Num. 23:7–10 and 18–24), which refer to the basic situation described in the story, may have been composed to go with the frame narrative: in them Balaam keeps saying why he cannot curse Israel. But the latter two blessings (24:3–9 and 15–24) seem disconnected from the frame story. Cut away their (nearly identical) opening verses, this approach claims, and these passages could well be two (or more) ancient prophetic oracles originally attributed to someone else entirely, or to no one in particular.7 In them, the speaker “predicts” the conquest of Edom by David but knows nothing of Edom’s subsequent resurgence. He mentions among the enemies of Israel the “Sethites” (24:17); this seems to be a memory from the distant past. All this makes these last two blessings sound particularly old. The surrounding prose, scholars say, does not. It is written in standard biblical Hebrew, of the sort spoken in the middle of the pre-exilic period. Still, the basic prose narrative, with its positive portrayal of Balaam, is probably earlier than the talking donkey incident, which seeks to denigrate Balaam. Indeed, the positive portrayal of Balaam would certainly fit well with the positive assessment of Balaam found in the words of the eighth-century prophet Micah:

O my people, remember what King Balak of Moab plotted, and what Balaam son of Beor answered him, and what happened from Shittim to Gilgal—so that you may know the saving acts of the LORD.

Though it is not entirely clear, this passage as well might seem to be presenting Balaam as a positive figure: he answers the wicked Balak, presumably by blessing Israel rather than cursing, and by that answer he apparently gives proof of the “saving acts” of God.8

Putting all this together: it seems to some scholars that Balaam’s last two blessings may go back to the time of David’s kingdom, if not earlier. These only later came to be attributed to Balaam, a legendary soothsayer, and the first two blessings added to them. At that time or possibly still later on, a surrounding narrative was created to contain them, one that presented Balaam as an altogether positive figure. Then—perhaps at a time when the very idea of a pagan prophet being addressed by Israel’s God had become anathema—the talking donkey was introduced, and with it, the presentation of Balaam as a buffoon. This negative assessment of Balaam may well have been the work of a priestly writer, scholars say, since such an assessment is reflected elsewhere in priestly writings. (Thus, Balaam is blamed for the Israelites’ sin at Baal Peor in Num. 31:16; Balaam’s well-deserved death by the sword is reported in Num. 31:8, cf. Josh. 13:22.) This negative portrayal was then picked up and carried forward by the ancient interpreters. Thus was born “Balaam the Wicked.”9

Moses’ Farewell

The book of Deuteronomy, as noted, contains a series of three discourses pronounced by Moses before his death. Addressing the people as they stood in Moab on the brink of their entry into Canaan, Moses reviewed for them the events of their recent history and all that God had done on their behalf. He stressed how important it was for Israel to keep the provisions of God’s covenant and observe all the laws that He had given them. The larger part of the book is then devoted to a detailed presentation of God’s laws—some of them basically the same as those presented elsewhere in the Torah, others quite new. The name of the book, Deuteronomy, means “second law” in Greek, a reflection of its Hebrew name in postbiblical sources, mishneh torah. This phrase, which appears in Deut. 17:18, was understood as meaning a “repetition of the law” and thus came to be used as the title of the whole book.48

In urging the people to remain faithful to God’s covenant with them, Moses stressed the central duty to recognize that God is the only deity in the universe: “Realize [this] today and turn it over in your mind: the LORD is indeed God, in heaven above and on the earth below; there is no other” (Deut. 4:39). This teaching is stressed repeatedly, but perhaps it is best known from a paragraph that came to play a central part in the teachings of Judaism and Christianity:

Hear, O Israel: The LORD is our God, the LORD alone. You shall love the LORD your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your might. Take to heart these words that I am commanding you today. Teach them to your children and speak about them when you are at home and when you are away, when you lie down and when you get up. Bind them as a sign on your hand, fix them as a frontlet on your forehead, and write them on the doorposts of your house and on your gates.

This paragraph came to be known as the “Shema” because of its opening word, “Hear!” (Hebrew, shĕma‘). As with the rest of the Torah, ancient readers did not see this paragraph as mere oratory or good advice, but as a commandment, one that God intended people to carry out scrupulously. But—come to think of it—how is someone supposed to do that? That is, what does the text mean by telling people to love God “with all your heart,” and how is that different from loving Him with all your soul and all your might?10 Moreover, when it says to take “these words” to heart and teach them to one’s children and speak about them, which words precisely are meant? And how much speaking about them is enough? As for binding them “as a sign on your hand and . . . a frontlet on your forehead”—surely God did not intend people to go around wearing “these words” on their arms and heads. But if not, what did He mean?

A modern reader would probably say that the basic import of this paragraph is: love God deeply and think about everything I (Moses) have been telling you—in fact, think about it all the time. While that might indeed be the overall meaning, ancient interpreters were eager to pin down anything in the Torah that might appear vague or general. This was their approach to “You shall not hate your brother in your heart” and to “You shall not take revenge or bear a grudge” (Lev. 19:17–19), and it was their approach to the Shema as well.

What, then, did it mean to love God “with all your heart”?

“With all your heart” means with your two inclinations, the inclination to do good and the inclination to do evil . . . and with all your soul, even should He demand your soul [that is, your death] . . .

Rabbi Akiba said: If the verse says “with all your soul,” then certainly this must include “all your might” too—why, then, should these words [“all your might,” bekhol me’odekha] be added? They mean: with whatever measuring-cup He measures out to you, whether good measure or ill, be thankful [modeh] to Him for all.

Sifrei Deuteronomy 32

To the ancient interpreters’ way of thinking, the human heart is divided between two inclinations, the one to good and the other to evil.11 It is not enough, therefore, to love God with one’s good inclination, since that will leave it still at war with the evil inclination; rather, one must work to convert the evil inclination to love God as well. Rabbi Akiba, finding the phrase “with all your might” somewhat anticlimactic after “with all your soul,” suggested that it be understood (because of the similar sound of the words meaning “your might” and “thankful”) as “for all things [I] thank You,” that is, that one ought to express gratitude to God no matter whether one’s portion is good or bad.12

As for “these words,” the phrase might indeed be taken to refer to anything or everything that Moses had said in his discourse thus far. Since, however, teaching them and speaking of them constantly seemed a potentially limitless task, ancient interpreters preferred to see in this phrase a reference to the words just spoken by Moses, starting with “Hear, O Israel.” A person was required to teach these words in particular to his or her children, and to recite them regularly. How regularly? The passage specified two particular moments in the day, “when you lie down and when you get up.” It therefore became customary to say the Shema twice a day, in the morning and at night.

He commands us that “on going to bed and rising,” men should meditate on the ordinances of God.13

Letter of Aristeas 160

With the entrance of day and of night, I shall enter into the covenant of God, and with the going out of evening and of morning, I shall speak His laws.

(1QS) Community Rule 10:10

Two times each day, at dawn and when it is time to go to sleep, let all acknowledge to God the gifts that He has bestowed upon them.

Josephus, Jewish Antiquities 4:212–13

This practice is maintained to this day in Judaism: day and night, the verses of the Shema are recited by religious Jews. Christians as well accord Deut. 6:5 special attention, since it was singled out in the Gospels as the “first commandment”:

One of the scribes . . . asked him [Jesus], “Which commandment is the first of all?” Jesus answered, “The first is, ‘Hear O Israel: the Lord our God, the Lord is one; you shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your mind, and with all your strength.’”

Mark 12:28–30 (also Matt. 22:35–38; Luke 10:25–28)

Some ancient interpreters took as metaphorical the commandment to “bind them as a sign on your hand, fix them as a frontlet on your forehead, and write them on the doorposts of your house and on your gates.” After all, elsewhere in the Bible (Song 8:6), a woman says to her beloved, “Set me as a seal upon your heart, as a seal upon your arm.” Surely she did not mean this literally, but only as a way of saying, “Don’t forget me! Think of me always!” Other interpreters, however—in keeping with the tendency to translate potentially vague or general commandments into the specific and concrete—took these words quite literally: what the Torah meant was indeed that people ought to attach these words to their frontlets (leather bands that, in the ancient world, held the hair in place, often topped with jewels or lockets), and that they ought similarly to bind these words on their arms, indeed, enclose them in little cases to be fastened to the doorposts and gates of their houses. This interpretation, attested in (among other things) the tefillin found among the Dead Sea Scrolls,14 is still the normative practice in today’s Judaism.

“Remember” and “Keep”

In reviewing the Ten Commandments (Deut. 5:6–21), Moses presented them in a wording somewhat different from that which appeared in the book of Exodus (20:1–17). For example, the fifth commandment in the Exodus version had said: “Remember the sabbath day,” but in Deuteronomy it began, “Keep [or guard] the sabbath day.” To be sure, even this minor difference was a problem for ancient interpreters: if the Torah was perfect in all its details (Assumption 3), then the two versions ought to match each other perfectly. Of course, it was possible to claim that, in reviewing things, Moses (or God speaking to Moses) had purposely changed a few things to drive home a new message. Still, why would it say “remember” first and “keep” second—logically, the Torah ought to have told people to keep the sabbath in Exodus and then reminded them in Deuteronomy.

Considering, however, the extraordinary circumstances that accompanied the giving of the Torah—a great divine voice speaking to all of Israel simultaneously—it occurred to some interpreters that the apparent conflict between “remember” and “keep” might not be an inconsistency at all, but a hint as to the extraordinary thing that went on that day (and was never repeated): in addressing the people directly, God had actually uttered both words simultaneously, and they had somehow absorbed both—something that is certainly impossible in normal, human-to-human communication:

“Remember” and “keep”—these two words were said [by God] in a single word.

Mekhilta deR. Ishmael, Yitro 7

That still begged the question of why. To some interpreters it seemed that, if the word “keep” was understood in its other sense of “guard,” then the Torah might actually be adding some specific teaching by its use of that word: not only was one to “remember” the sabbath and observe all its rules during the twenty-four hours it was in effect, but one ought as well to cease weekday activities a little before the sabbath, in effect, guarding its beginning lest any forbidden work be done inadvertently after the start of the sabbath:

No one shall do work on Friday from the time when the sphere of the sun is distant from the gate [by] its [the sun’s] full size, for this is why it is said, “Guard the sabbath day to sanctify it” [Deut. 5:12].

Damascus Document 10:14–17

Other interpreters extended this idea, suggesting that a little time be added to the sabbath at both ends, fore and aft:

“Remember” and “guard”—remember before [the sabbath starts] and guard it after [the sabbath is over]. From this it was deduced that one is to add [time] from the profane [that is, from the rest of the week] to the sacred [that is, the sabbath].

Mekhilta deR. Ishmael, Yitro 7

Modern scholars, of course, are inclined to chalk up such differences between the Exodus and Deuteronomy versions of the Ten Commandments to human beings.15 As already mentioned, they note that the two sabbath laws in Exodus and Deuteronomy are actually quite different in what follows their first words:

Remember the sabbath day, and keep it holy. Six days you shall labor and do all your work. But the seventh day is a sabbath to the LORD your God; you shall not do any work—you, your son or your daughter, your male or female slave, your livestock, or the alien resident in your towns. For in six days the LORD made heaven and earth, the sea, and all that is in them, but rested the seventh day; therefore the LORD blessed the sabbath day and consecrated it.

Exod. 20:8–11

Observe the sabbath day and keep it holy, as the LORD your God commanded you. Six days you shall labor and do all your work. But the seventh day is a sabbath to the LORD your God; you shall not do any work—you, or your son or your daughter, or your male or female slave, or your ox or your donkey, or any of your livestock, or the resident alien in your towns, so that your male and female slave may rest as well as you. Remember that you were a slave in the land of Egypt, and the LORD your God brought you out from there with a mighty hand and an outstretched arm; therefore the LORD your God commanded you to keep the sabbath day.

Deut. 5:12–15

Neither of these versions, scholars feel, can correspond to the “original” sabbath commandment. The original text must have been much shorter: “You shall not do any work on the sabbath day,” or the like.16 The current versions therefore reveal something about their final editors. The text in Exodus 20, scholars say, shows the influence of a priestly editor, who has added his justification for the sabbath, namely, God’s having rested on the seventh day—the same justification that is found in the priestly version of the creation in Genesis 1. The Deuteronomy version, by contrast, says nothing at all about God resting. Instead, scholars point out, it is strictly a day of human rest and, in keeping with the overall “humanitarian” quality of that book, the text says twice that “your male and female slave” are to be given a day off as well. The justification for this, the Deuteronomy text adds, is the whole story of the Exodus, a favorite theme of that book: you know what it means to be a slave, so let your slaves rest with you.

Dire Consequences

After giving Israel a great body of laws (Deuteronomy 12–26), Moses told the people what they were to do when they arrived in the land of Canaan: in the area of Shechem, a ceremony was to mark their reacceptance of God’s covenant, with half the tribes standing on Mount Gerizim and half on Mount Ebal (Deuteronomy 27). He then warned the Israelites to observe scrupulously the conditions of this covenant: should they do so, God would bless them and provide for all their needs; but should they fail to do so, they would suffer a series of disasters. This section—similar to chapter 26 of Leviticus—is graphic in the extreme:

But if you will not obey the LORD your God by diligently observing all his commandments and decrees, which I am commanding you today, then all these curses shall come upon you and overtake you:

Cursed shall you be in the city, and cursed shall you be in the field. Cursed shall be your basket and your kneading bowl. Cursed shall be the fruit of your womb, the fruit of your ground, the increase of your cattle and the issue of your flock. Cursed shall you be when you come in, and cursed shall you be when you go out.

The LORD will send upon you disaster, panic, and frustration in everything you attempt to do, until you are destroyed and perish quickly, on account of the evil of your deeds, because you have forsaken Me. The LORD will make the pestilence cling to you until it has consumed you off the land that you are entering to possess. The LORD will afflict you with consumption, fever, inflammation, with fiery heat and drought, and with blight and mildew; they shall pursue you until you perish. The sky over your head shall be bronze, and the earth under you iron. The LORD will change the rain of your land into powder, and only dust shall come down upon you from the sky until you are destroyed.

This might seem enough, but this list of the dire consequences of disobedience goes on and on, for another forty-four verses. (This on top of the similar list of warnings in Lev. 26:14–43!) For ancient readers of the Bible, however, none of this could seem particularly surprising. God was certainly right to have warned Israel at length, and in the strictest terms—after all, no one, according to biblical jurisprudence, could be punished without having received prior warning,17 and Israel was indeed punished severely for not keeping God’s commandments. In the eighth century BCE, God allowed the northern kingdom of Israel to fall victim to the invading Assyrian army as punishment for their disobedience, and when, still not chastened, the southern kingdom of Judah continued its heedlessness, it too fell to a foreign army, the Babylonian, in the sixth century BCE. Indeed, at one point this passage of curses in Deuteronomy seemed to allude specifically to such a foreign invasion:

The LORD will bring a nation from far away, from the end of the earth, to swoop down on you like an eagle, a nation whose language you do not understand, a grim-faced nation showing no respect to the old or favor to the young. It shall consume the fruit of your livestock and the fruit of your ground until you are destroyed, leaving you neither grain, wine, and oil, nor the increase of your cattle and the issue of your flock, until it has made you perish. It shall besiege you in all your towns until your high and fortified walls, in which you trusted, come down throughout your land; it shall besiege you in all your towns throughout the land that the LORD your God has given you. In the desperate straits to which the enemy siege reduces you, you will eat the fruit of your womb, the flesh of your own sons and daughters whom the LORD your God has given you. Even the most refined and gentle of men among you will begrudge food to his own brother, to the wife whom he embraces, and to the last of his remaining children, giving to none of them any of the flesh of his children whom he is eating, because nothing else remains to him, in the desperate straits to which the enemy siege will reduce you in all your towns. She who is the most refined and gentle among you, so gentle and refined that she does not venture to set the sole of her foot on the ground, will begrudge food to the husband whom she embraces, to her own son, and to her own daughter, begrudging even the afterbirth that comes out from between her thighs, and the children that she bears, because she will eat them in secret for lack of anything else, in the desperate straits to which the enemy siege will reduce you in your towns . . .

The LORD will scatter you among all peoples, from one end of the earth to the other; and there you shall serve other gods, of wood and stone, which neither you nor your ancestors have known. Among those nations you shall find no ease, no resting place for the sole of your foot. There the LORD will give you a trembling heart, failing eyes, and a languishing spirit. Your life shall hang in doubt before you; night and day you shall be in dread, with no assurance of your life. In the morning you shall say, “If only it were evening!” and at evening you shall say, “If only it were morning!”—because of the dread that your heart shall feel and the sights that your eyes shall see. The LORD will bring you back in ships to Egypt, by a route that I promised you would never see again; and there you shall offer yourselves for sale to your enemies as male and female slaves, but there will be no buyer.

This picture of a foreign invader—not a neighboring kingdom, but one “from the end of the earth . . . a nation whose language you do not understand”—certainly matched the historical circumstances that eventually overtook Israel, and the description of unbearable suffering under foreign siege corresponded, alas, to the gruesome details of cannibalism and other horrors catalogued elsewhere in the Bible (Lam. 2:20–21; 4:8–10). Yet even if Israel disobeyed and suffered all these dire consequences, the people knew that that would not spell the end to their existence. The Torah had already given them such assurance in the earlier set of warnings (Lev. 26:44–45), and now Moses reiterated the promise more explicitly:

When all these things have happened to you, the blessings and the curses that I have set before you, if you call them to mind among all the nations where the LORD your God has driven you, and return to the LORD your God, and you and your children obey Him with all your heart and with all your soul, just as I am commanding you today, then the LORD your God will restore your fortunes and have compassion on you, gathering you again from all the peoples among whom the LORD your God has scattered you. Even if you are exiled to the ends of the world, from there the LORD your God will gather you, and from there He will bring you back. The LORD your God will bring you into the land that your ancestors possessed, and you will possess it; He will make you more prosperous and numerous than your ancestors.

This prediction came true as well, at least for the Kingdom of Judah. Although its citizens were sent into exile into Babylon, eventually the exile ended and, just as He had rescued the Israelite slaves from Egypt, God led the exiles back from Babylon into their ancestral homeland. In this respect, the Torah’s words were indeed carried out to the letter.

Deuteronomy and Ancient Near Eastern Treaties

As already observed, some modern scholars see in the very form of the book of Deuteronomy a structure reminiscent of that of ancient suzerainty treaties: historical prologue (1–4); insistence on exclusive loyalty to the suzerain (12–13, preceded here by the general exhortations of chapters 5–11); further covenant stipulations (14–26); provisions for deposit of the text (27:3–8; 31:9) and its public recitation (31:11–13); blessings and curses (27:15–28:68); and even a kind of covenant “witness” (31:19, 28; 32:1) in place of the usual gods who were mentioned as witnesses in human-to-human treaties. The match is not perfect: the elements appear in a slightly different order and form, and Deuteronomy as a whole is much longer than any extant suzerainty treaty. Still, the presence of the same basic six elements has convinced many scholars that the resemblance cannot be a matter of chance.

That supposition has been bolstered by a number of close verbal ties between, specifically, the words of warning in Leviticus and Deuteronomy and similar warnings appended to a number of ancient Near Eastern treaties. For example:

The sky over your head shall be copper, and the earth under you iron.

I will make your skies like iron and your earth like copper.

May all the gods . . . turn your ground into iron, so that no one may plow it. Just as rain does not fall from a bronze sky, so may rain and dew not come upon your fields and meadows.

Vassal Treaty of Esarhaddon 528–3118

Similarly:

The LORD will afflict you with madness, blindness, and confusion of mind; you shall grope about at noon as blind people grope in darkness, but you shall be unable to find your way.

May Shamash . . . deprive you of the sight of your eyes, so that they will wander about in darkness.

Vassal Treaty of Esarhaddon 422–24

You shall become engaged to a woman, but another man shall lie with her. You shall build a house, but not live in it. You shall plant a vineyard, but not enjoy its fruit . . . Your sons and daughters shall be given to another people, while you look on.

May [the deity of the star Venus], the brightest of stars, make your wives lie in your enemy’s lap while your eyes look on. . . . May your sons not be masters of your house. May a foreign enemy divide all your goods.

Vassal Treaty of Esarhaddon 428–30

She who is the most refined and gentle among you . . . will begrudge food . . . to her own daughter, begrudging even the afterbirth that comes out from between her thighs, and the children that she bears, because she is eating them in secret for lack of anything else, in the desperate straits to which the enemy siege will reduce you in your towns . . .

A mother will lock her door against her daughter. In your hunger, eat the flesh of your sons! In the famine and want, may one man eat the flesh of another.

Vassal Treaty of Esarhaddon 448–50

Nor do these exhaust the ancient Near Eastern parallels. A ninth-century inscription from Tell Fakhariyeh warned of the penalties for removing the king’s name from its monument:

One hundred women will bake bread in a single oven and not fill it.19

Similarly:

When I break your staff of bread, ten women shall bake your bread in a single oven, and they shall dole out your bread by weight; and though you eat, you shall not be satisfied.

All these resemblances suggest to scholars that the imprecations at the end of Leviticus and Deuteronomy were themselves rooted in the standard treaty curses of the ancient Near East—not only the general idea of such curses, but the specific things that the treaties invoked. What is more, the specific resemblances between Deuteronomy and the vassal treaty of the Assyrian king Esarhaddon, who ruled from around 681 to 669 BCE, would support the connection some scholars have made between other elements of Deuteronomy and the influence of Assyrian culture in the region (particularly strong during the years 740–640 BCE).

Renewing the Covenant

If so, then what Deuteronomy essentially describes is a great covenant between God and Israel—not the one at Mount Sinai, but another one concluded in the plains of Moab just before Moses’ death.20 Thus, having spelled out the covenant’s conditions of exclusive loyalty and all the other stipulations, and having then concluded with the covenant’s “teeth” (that is, the list of calamities that will befall Israel if they do not obey), Moses makes explicit what is going on:

You are standing today, all of you, before the LORD your God—your chiefs and leaders, your elders and your officials, every notable in Israel; [moreover] your children, your women, and the aliens who are in your camp, from those who cut your wood to those who draw your water—as you enter into the covenant of the LORD your God, sworn by an oath, which the LORD your God is making with you today; in order that He may establish you today as His people, and that He may be your God, as He promised you and as He swore to your ancestors, to Abraham, to Isaac, and to Jacob.

Moses stresses that this covenant is to cover not only those who are physically present, but future generations as well:

I am making this covenant, sworn by an oath, not only with you who stand here with us today before the LORD our God, but also with those who are not here with us today . . .

He then presents the acceptance of this agreement between God and Israel in the starkest terms:

Surely, this commandment that I am commanding you today is not too hard for you, nor is it too far away. It is not in heaven, that you should say, “Who will go up to heaven for us, and get it and tell it to us, so that we can observe it?” Nor is it beyond the sea, so that someone should say, “Who will cross to the other side of the sea for us, and get it and tell it to us, so that we can observe it?” No, the word is very near to you; it is in your mouth and in your heart for you to observe.

See, I have set before you today life and well-being, death and adversity. If you obey the commandments of the LORD your God21 that I am commanding you today—loving the LORD your God, walking in His ways and keeping His commandments, decrees, and ordinances—then you will live and grow greater, and the LORD your God will bless you in the land that you are entering to possess. But if your heart turns away and you do not obey, but are led astray to bow down to other gods and serve them, then I declare to you today that you shall surely perish; you shall not live long in the land that you are crossing the Jordan to enter and possess.

I call heaven and earth to witness against you today that I have set before you life and death, a blessing and a curse. Choose life—so that you and your descendants may live, loving the LORD your God, obeying Him, and holding fast to Him; for that means life to you and length of days, so that you may live in the land that the LORD swore to give to your ancestors, to Abraham, to Isaac, and to Jacob.

The Life of Torah

These words resounded in the ears of later generations of Jews and Christians. If God demanded all-out devotion, they were prepared to give it. Pledging themselves to God, they felt, was not merely a matter of accepting God’s existence and dominion, but of expressing that acceptance in concrete terms, in their own lives. In a sense, all aspects of Jewish and Christian devotion—attendance at religious services, but also individual prayers; the study of Scripture, whether in a public place or at home; and dozens of other little acts intended as a carrying out of God’s will—find at least part of their origin and inspiration in these words of Deuteronomy. The starkness of the choice described here—between good and ill, a blessing and a curse—bespeaks the pure, unambiguous world of the soul.22 Implicit in such a choice, therefore, is always the possibility of asceticism; after all, how much devotion can ever be enough? So it was that, from biblical times onward, certain individuals chose to give their lives over to God. The vow of the biblical nazirite (Numbers 6) was succeeded by other forms of self-denial and self-affliction, as represented by the (probably) monastic Jewish community at Qumran and the ascetic Thereputae described by Philo of Alexandria (De Vita Contemplativa), as well as by later, indisputably monastic communities of Christian men and women—not to speak of the numerous celibates, cave dwellers, pillar sitters, and other ascetics, and beyond these the actual martyrs (Jews and Christians at first, and then Jews in large numbers) who have preferred death to breaking with their devotion to God.

In less drastic form, devotion to God has found expression in the lives of countless ordinary individuals who, turning from the material pleasures of this world, set for themselves a regimen of divine service. For Jews of postbiblical times, the words of the Mishnah have carried forward Deuteronomy’s central theme:

This is the path of Torah: Bread and salt shall you eat, and drink water by measure; you shall sleep upon the ground, and live a life of privation, and in the Torah shall be your work. And if you do thus, “You shall be happy, and it will be well with you” (Ps. 128:2)—“happy” refers to this world, and “well” to the world to come.

The Torah is supreme, for it gives life to those who perform it[s commandments] in this world and in the world to come, as it is said, “It is a tree of life to those who hold on to it, and all who maintain it are blessed” (Prov. 3:18).

m. Abot 6:4, 7

Telling, too, is the well-known Talmudic anecdote concerning Rabbi Akiba (second century CE):

Once, the wicked regime [Rome] decreed that Jews be forbidden to study the Torah. Papos son of Judah subsequently found Rabbi Akiba nonetheless convening groups in public for the study of Torah. “Akiba,” he said, “are you not afraid of the regime?” He said, “Let me answer you with a comparison. It is like a fox that was walking along the riverbank when he saw some fish moving in groups from place to place. He said to them: ‘What are you fleeing from?’ They said to him: ‘From the nets that the human beings cast over us.’ He said to them: ‘Wouldn’t you like to climb up onto the dry land so that you and I might live together as your ancestors and mine once did?’ They said: ‘Are you indeed the one who is alleged to be the cleverest of animals? You are not clever but foolish! For if there is danger in the place where we do live [that is, our natural environment], is it not all the more so in the place where we must die?’ So it is with us now: for we sit and study Torah, about which it is said, ‘For it is your life and your length of days’ (Deut. 30:20); were we to abandon it, we would be in far greater danger.”

b. Berakhot 61b

The meaning of “loving” God in the various passages cited from Deuteronomy may seem self-evident; but is it really? In 1963, an American Jesuit teaching in Rome published an article that, in its own way, gave the world of biblical scholarship another jolt.23 William L. Moran was part of that vanguard of Roman Catholic scholars who emerged after the encyclical Divino Afflante Spiritu (1943), the first papal document that encouraged Catholics to become thoroughly trained in the ways of modern biblical research. Moran studied with W. F. Albright at Johns Hopkins and ultimately specialized in ancient Akkadian texts and their relationship to the world of the Bible.24

While teaching at the Pontifical Biblical Institute at Rome, Moran was struck by something in the same Vassal Treaty of Esarhaddon mentioned above. Esarhaddon had apparently been eager to insure that his vassals would continue to be loyal to his successor, Assurbanipal. At one point in his treaty, therefore, he commanded his vassals: “You shall love Assurbanipal as yourselves.” This struck Moran as an odd choice of language: love? Surely the vassals were not being told to become enamored of the future king’s winning personality! It seemed to Moran as if love here must have less to do with emotion than with loyalty, political loyalty. Although the Akkadian word for love came from a different Semitic root, Moran set out to investigate the various ways in which the Hebrew word for love, ’ahab, was used in the Bible.

What he found was that ’ahab was indeed sometimes used for emotion: Jacob loves Rachel and so goes to work for her father for seven years (Gen. 29:18). At other times, however, people in the Bible seem to love more in the Esarhaddon way. This seemed especially true of the book of Deuteronomy, where loving God is often directly juxtaposed to serving God and keeping his commandments:

So now, O Israel, what does the LORD your God require of you? Only to fear the LORD your God, to walk in all His ways, to love Him, to serve the LORD your God with all your heart and with all your soul, and to keep the commandments of the LORD your God and His decrees that I am commanding you today, for your own well-being.

Deut. 10:12

You shall love the LORD your God, therefore, and keep His charge, His decrees, His ordinances, and His commandments always.

If you will only heed His every commandment that I am commanding you today—loving the LORD your God, and serving Him with all your heart and with all your soul . . .

Deut. 11:13

If you will diligently observe this entire commandment that I am commanding you, loving the LORD your God, walking in all His ways, and holding fast to Him . . .

Choose life so that you and your descendants may live, loving the LORD your God, obeying Him, and holding fast to Him . . .

Remarkably, Moran found, although Deuteronomy sometimes compared the relationship of God to Israel to that of a father to his son (Deut. 8:5; 14:1), the word for love was not invoked there, where one would expect some expression of emotional attachment. Instead, Israel was commanded to love God only in the ways seen above, where love is virtually a synonym of “fear,” “obey,” “serve,” and the like. And come to think of it, how can you command someone to love someone else? If the word means anything like “love” in our sense, that would seem to be impossible.

Esarhaddon was not the only ancient Near Eastern potentate to demand “love” from his servants. A Canaanite vassal of Pharaoh writes in one of the El-Amarna letters: “My lord, just as I love the king my lord, so [does] the king of Nuhašše [love him, and] the king of Ni’i . . .—all these kings are servants of my lord.” Here, apparently, to love is to be a servant. Another ancient king described a civil war in these terms: “Behold the city! Half of it loves the sons of ‘Abd-Aširta, half of it [loves] my lord.”

Thus, the peoples of the ancient Near East would probably have been puzzled by the observation attributed to Talleyrand, “Nations do not have friends; they have interests.” National interests in the ancient Near East were often presented precisely in terms of friendship (that is, love). Thus, Hiram of Tyre is called David’s “friend” (1 Kings 5:1—from the same root, ’ahab), but they were really only political allies. In 2 Sam. 19:6–7, Joab accuses David of “loving those who hate you and hating those who love you,” that is, crying over the death of Absalom, his political opponent; David’s “friends” are referred to in the next verse as “your servants.” “All Israel and Judah loved David,” it says in 1 Sam. 18:16, but this was not a matter of love so much as of political support, and the rest of the sentence goes on to make clear why: “for it was he who went out and came in” (“going out and coming in” is a biblical idiom meaning “to lead,” often, as here, to lead the army).

In short, Moran’s article suggested that when the Shema said, “You shall love the LORD your God with all your heart,” it had in mind nothing like the all-out, deep-in-the-heart devotion understood by later interpreters, loving God with one’s inclination to evil as well as to good, or loving God so profoundly as to feel gratitude to Him no matter which “measuring cup” He uses to measure out one’s portion. And it certainly had nothing to do with the unio mystica of medieval adepts, nor yet with Spinoza’s amor Dei intellectualis. All the verse meant was to do God’s bidding. The point is made clear time and again in Deuteronomy: “And so, if you carefully heed My commandments, which I am commanding you today—to love the LORD your God and to serve Him with all your heart and with all your soul . . .” (Deut. 11:13). Here too, loving and serving are said in the same breath because they are essentially the same thing.

This concept of love as service, Moran felt, may have been a fundamental theme in Deuteronomy, but, he asserted, it was older than that. Noting its presence in both versions of the Ten Commandments—

. . . for I the LORD your God am a jealous God, punishing children for the iniquity of parents, to the third and the fourth generation of those who reject Me, but showing kindness to the thousandth generation of those who love Me and keep My commandments.

—Moran concluded that the idea of loving God went back to the very beginning of the idea of a covenant, a treatylike agreement, between God and Israel. “The Deuteronomic love of service is older [than the writings of the prophet Hosea],” he wrote, “probably as old, or almost as old, as the covenant itself.”25

The Song of Moses

Having concluded his solemn charge to the people of Israel, Moses made his last preparations to bid them farewell. God had repeatedly told him that he could not enter Canaan himself but would have to die on the far side of the Jordan (Num. 27:12–14; Deut. 1:37; 3:27; 31:2, 32:49–50; 34:4). He knew he would have to submit to God’s decree.26 Before taking his final leave, however, Moses recited for the people a prophetic song that might serve as a warning to future generations (the “Song of Moses,” Deuteronomy 32), and then he blessed each of the tribes in turn (Deuteronomy 33).

On the basis of their archaic language and other features, both these chapters have been judged by modern scholars to be older than the rest of Deuteronomy. The precise referents of some parts of the Song of Moses are in dispute among different scholars, but they note in particular its way of accounting for Israel’s privileged place in the world:

Remember the days of old, consider the years long past;

Ask your father, and he will inform you; your elders, and they will tell you.

When the Most High established nations and split up the sons of men,

He fixed the boundaries of peoples according to the number of gods.27

But the LORD’s own portion is His people, Jacob His allotted share.

What is striking to scholars about this passage is, first of all, the divine names. The “Most High” (Hebrew, ‘Elyon) was actually how the ancient Canaanites referred to the highest of the gods in their pantheon. Scholars note that this name also appears in the Bible a few times in reference to the God of Israel, though it is not clear to them at what point the names ‘Elyon and YHWH might have become synonymous in Israel. (In Gen. 14:18–21, the Canaanite Melchizedek seems to mention ’El ‘Elyon as his own deity, but Abraham then apparently identifies this god—perhaps syncretistically—with the God of Israel.) In the passage just cited (Deut. 32:7–9), it seems clear that Israel’s God is meant, but, scholars say, by using the name ‘Elyon this passage may be invoking an ancient (perhaps pre-Israelite) creation motif. In addition to this, the original text of this passage also referred to the “sons of El” or “the sons of God” (verse 8; the traditional Hebrew text apparently amended this to “sons of Israel” to avoid the polytheistic implications). Again, it is difficult to know how this appellation was intended to be understood, but in the context of the song, scholars say, it is part of an explanation of how the world ended up the way it did. The song says that when the “Most High” was dividing up the human population into different nations and granting each its national territory, He did so on the basis of the total number of the “sons of God” (or “sons of El”). That is, things were arranged so that each of these lesser deities would have his own nation to look after. But God kept Israel for Himself: “the LORD’s own portion is His people, Jacob His allotted share.” It is certainly significant that there is no hint here of monotheism, the belief that only one God exists—indeed, the opposite seems to be just the point. Nor is any reason offered for God’s choice of Israel—it was apparently simply Israel’s good fortune that things turned out that way. This contrasts somewhat with the rest of Deuteronomy, which stresses God’s love of Israel’s ancestors Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob as the reason for Israel’s privileged position. (The Song of Moses makes no mention of these ancestors—in fact, it seems to suggest that Israel first encountered God in the wilderness after the exodus [verse 10], a theme echoed in Hos. 2:14–15 and Jer. 2:2.)

Scholars have pointed to what they consider a later passage in Deuteronomy that says something rather similar. There Moses warns the Israelites:

And when you look up to the heavens and see the sun, the moon, and the stars, all the host of heaven, do not be led astray and bow down to them and serve them, things that the LORD your God has allotted to all the peoples everywhere under heaven.

Here too, God has assigned the sun, the moon, and the stars—astral deities worshiped by the Assyrians and others—to all other peoples except Israel. Apparently, the idea that God Himself was responsible for the polytheism in other nations became an accepted explanation for polytheism’s continued existence.

Moses Blesses the People

When, next, Moses turns to bless the different tribes of Israel, he seems to be following the same pattern as Jacob, who had blessed each of his twelve sons just before his death (Genesis 49). Modern scholars, however, have noticed significant differences between these two sets of blessings and have relied on them to support some ideas (somewhat speculative, they concede) about Israel at a very early period in its history.

Thus, about the tribe of Reuben, Moses says: “Let Reuben live and not die” (Deut. 33:6). Scholars see in this a reflection of Reuben’s endangered existence as an independent entity. Even at the time of Genesis 49, they say, the tribe of Reuben was apparently not flourishing; that is why, they believe, Jacob is presented as rebuking his son Reuben for his alleged sin with his father’s concubine (Gen. 49:3–4). “You’ll have privilege no more,” Jacob tells him, thereby “predicting” this tribe’s precipitous fall from first place. Now, in Deut. 33:6, that fall seems to be bordering on extinction: Reuben (that is, the tribe) is on the brink of “death.” Not long after these lines were written, some scholars hold, the tribe of Reuben did, in fact, disappear forever. Originally located on the far side of the Jordan, it may have begun to be absorbed by its neighbors as early as the eleventh century BCE, perhaps amalgamating with the neighboring tribe of Gad or becoming part of nearby Moab.28 In any case, according to one scholar, “in the time of David . . . Reuben as a tribal entity with a fixed territory has disappeared.”29

Simeon may have suffered a similar fate, at least to judge by this same set of blessings in Deuteronomy: Moses does not even mention Simeon. The Simeonites had been located south of Judah, so it may be, scholars believe, that at some early point the tribe simply came to be absorbed by the more powerful Judah. As for the fourth tribe, Levi, it too seems to have undergone a change—but not extinction:

And of Levi he [Moses] said [to God]:

Give to Levi Your Thummim,49 and Your Urim to Your loyal one,

whom You tested at Massah, with whom You contended at the waters of Meribah . . .30

May they teach Jacob Your ordinances, and Israel Your law;

Let them place incense before You, and whole burnt offerings on Your altar.

Bless, O LORD, his substance, and accept the work of his hands;

crush the loins of his adversaries, of those that hate him, so that they do not rise again.

In Jacob’s joint blessing of Simeon and Levi (Gen. 49:5–7), the two tribes had seemed destined to share the same fate: “I will divide them in Jacob and scatter them in Israel.” And indeed, the tribe of Levi does seem to have lost any concentrated tribal territory it once had, being allocated instead a number of separate cities in different parts of the country (according to Josh. 21:1–40, forty-eight in all).31 The Levites thus lost out on a large tribal homeland. But in Moses’ blessing they have clearly gotten a consolation prize: the Levites have become the priestly tribe par excellence. Moses declares that the Levites are to receive the Urim and Thummim and to be assigned the (priestly) job of instructing the nation in God’s law as well as offering incense and sacrifices in the temple. While the association of the Levites with the priesthood is certainly quite ancient, scholars note that, at a very early time, there may not have been a fixed, hereditary priesthood associated with one tribe. After all, Cain and Abel and Noah and Abraham are all represented as offering sacrifices to God, and none of them is described as a Levite or trained in the priestly arts. Indeed, a certain wealthy man in the book of Judges, having hired a Levite for his household, asserts: “Now I know that the LORD will be good to me, since the Levite has become my priest” (Judg. 17:13). Apparently a non-Levite would not have been as sure a bet, but the text may be implying that such a person was not beyond consideration for the job.32

When at last Moses passes into the next world, the Torah is unstinting in its eulogy. Its words form a fit conclusion to the Five Books of Moses:

Moses was one hundred twenty years old when he died. His eyes had not dimmed nor had his vigor diminished. The Israelites wept for Moses in the plains of Moab thirty days; then the period of mourning for Moses was ended . . . Never since has there arisen a prophet in Israel like Moses, whom the LORD knew face to face, with all the signs and wonders that the LORD sent him to perform in the land of Egypt, against Pharaoh and all his servants and his entire land, and all the great might and fearsome power that Moses performed before all of Israel.

For readers ever after, Moses has always stood as the model of the Hebrew Bible’s greatest prophet. In late antiquity and the Middle Ages, commentators and philosophers sought to elaborate on the above passage, asserting that no other prophet had ever attained to Moses’ status. Indeed, even in more recent times, Moses has exercised a special hold on the very image of prophecy. In the famous prologue of Paradise Lost, the English poet John Milton called upon Moses’ source of divine inspiration to guide him in his own writing:

Sing, Heav’nly Muse, that on the secret top

Of Oreb5033 or of Sinai, didst inspire

That Shepherd, who first taught the chosen Seed,

In the Beginning how the Heav’ns and Earth

Rose out of Chaos . . .

In still later times, Moses became the model of the Romantic poet, leaving the noisy throng of humanity behind as he ascended to Sinai/Parnassus, where true inspiration is to be found:

Prophète centenaire environné d’honneur,

Moïse était parti pour trouver le Seigneur.51

Alfred de Vigny, Moïse

An Obvious Gap

Here ends the Pentateuch. The preceding pages are not given to simple summary, but, as far as the composition of the Bible’s first five books is concerned, one obvious conclusion emerges: a great gap separates the traditional view of the Pentateuch in Judaism and Christianity from the various reconstructions of modern scholars.

The traditional view, of course, sees the entire Pentateuch as the word of God, passed on to Israel through a single prophet, Moses. Moses began his writing by describing how the world was created in six days (obviously, no human could know such a thing unless it had been communicated to him by God) and went on to chronicle the first generations of humanity, from Adam and Eve to the great flood and on to Abraham and Sarah, Isaac and Rebekah, and Jacob and his four wives—the immediate ancestors of the people of Israel. The story of Joseph explained how Israel’s ancestors then came to dwell for a time in Egypt, where they were eventually enslaved by a wicked pharaoh. The Israelites managed to weather their extended captivity, finally escaping Egypt under the leadership of Moses. After their miraculous crossing of the Red Sea, they made their way to Sinai, where God adopted them as His special people, a “kingdom of priests and a holy nation” bound to Him by the conditions of His great covenant. The detailed laws that followed—not only the ones presented in Exodus 21–23, but the many other laws contained in the next three books—were offered to Israel as a divine guide to daily life. This was the greatest of gifts, and these laws were, as we have seen, lovingly interpreted in all their details.

The forty years of Israel’s wanderings in the wilderness were not easy; military confrontations, internal strife, and the day-to-day difficulties of life on the move all took their toll. But in the end, Israel emerged strong and ready to proceed with their final entrance into the land that God had promised them. The divine presence, accompanying them in the tabernacle that they had constructed, was their greatest source of strength. Although Moses would no longer be with them, his former servant Joshua had inherited his mantle. It was he who would take the lead as the Israelites crossed the Jordan into Canaan.

Modern scholars find most of the foregoing quite incompatible with the truth as they know it. Moses cannot, they assert, have been the author of the Pentateuch—indeed, no one person could be, since the text contains so many internal inconsistencies and contradictions. The events recounted in the Pentateuch are likewise seen as largely ahistorical. The stories of Adam and Eve, Cain and Abel, Abraham and Isaac and Jacob are generally viewed as etiological narratives composed in an age far distant from the events they describe; their real purpose was not to record past history, but to explain various aspects of then-current reality through reference to one or another invented ancestor. Other parts of the Pentateuch, while they may have some historical basis, are viewed as greatly exaggerated. If there was an Exodus, scholars say, it can have involved only a tiny part of the future Israel, perhaps a few hundred souls at most. The number and nature of the plagues that may have struck Egypt, and what really happened at the Red Sea will, scholars say, probably never be known—but again, the Pentateuch’s version seems unlikely and is, in any case, contradicted by the evidence of archaeology, Egyptology, and even the biblical text itself. For similar reasons, the Israelites’ forty years in the wilderness, their construction of the elaborate tabernacle that accompanied them, and their ultimate entry into, and conquest of, Canaan raise numerous difficulties in the minds of scholars. Very little of this, they say, will square with evidence assembled from elsewhere.

As for modern scholars’ views on how the Pentateuch came into existence, there is currently little consensus. For many scholars, the Pentateuch began with orally transmitted traditions going back to before the time of David—etiological tales connected with one or another sacred site or eponymous founder, schematic narratives reflecting early relations with neighboring countries or tribes, and other faint recollections of events from the distant past. With the passage of time, these individual traditions may have been grouped around the figures of different ancestors—Abram/Abraham, Jacob/Israel, and so forth—or around specific themes such as the Exodus from Egypt.34 But how those ancient traditions may have led to the collections of texts currently identified as J and E, and when and under what circumstances priestly texts and priestly editors came to intervene in the creation of the Pentateuch’s final form, is the subject of fierce debate. Likewise, while the legal code that stands at the heart of Deuteronomy is generally dated to the time before Josiah and its original composition located in the north, the circumstances of the creation of the current book of Deuteronomy as well as the role of a Deuteronomy-influenced writer or editor in the Pentateuch’s final shape are also in dispute.

What modern scholars certainly do agree on is that the Pentateuch in its current form represents the writings of a number of disparate people and schools, and that it came together through a series of different recensions. Its diverse origins are attested even in its earliest stages. Thus, while it used to be maintained that J and E were the creation of individual historians, many scholars today find this unlikely. There are too many internal contradictions within the J complex of texts to support the idea that they were the work of one person; moreover, it seems unlikely that the E texts that we possess could in themselves have been an integrated, sequential history. How, or even if, these two collections of texts came later to be combined into a single history (the hypothetical text scholars call JE) also remains unclear, though one hypothesis is that, with the fall of the northern kingdom of Israel, refugees fleeing south brought with them some of the E texts, and these were subsequently woven into a new version of national history.

The intervention of different authors and editorial hands did not end there. If scholars are correct in identifying P and H as pre-exilic sources, then the creation and integration of at least some priestly material into the non-priestly history may go back to pre-exilic times. As for Deuteronomy, scholars believe that the law code that stands at its heart was once an independent document that was later combined with the surrounding historical framework; even this framework, however, was not the creation of a single author. The hand of a Deuteronomic editor has been detected here and there in Genesis–Numbers as well. Many current scholars identify a member of the H school as the Pentateuch’s very last editor; his activity would have taken place shortly after Israel’s return from the Babylonian exile, according to some,35 though others would prefer to speak of a more diffuse and prolonged process, extending well into the Persian period.

The oldest traditions of interpretation in connection with the Pentateuch go back long before this final editing. Scholars since the nineteenth century have observed how Deuteronomy, for example, seems to have recast older laws in Exodus on the basis of this or that interpretation of their precise wording; similarly, later narrative traditions sometimes appear to be interpreting older versions of the same events, just as later prophecies, as we shall see, sometimes rework earlier ones. But the interpretation of Scripture appears to have become a major, recognizable activity—an academic specialty, as it were—only in the postexilic period. Those given charge of Scripture and its interpretation were by and large part of the emerging cadre of teachers and sages influenced by the great wisdom traditions of the ancient Near East. These sages sought to put their own “spin” on the Pentateuch in particular.36 The Pentateuch was now viewed, as Ben Sira and other sages attest (Sir. 24:23; Bar. 3:36–41), as nothing less than divine wisdom in written form, one great book of legal and ethical instruction. As a result, the Pentateuch as a whole came to be radically transformed: its etiological narratives now became moral exempla, and its ancient laws became an up-to-date guide for daily life today. Rather than a record of the past, the Pentateuch became, like all wisdom writings, a set of instructions for the present. Indeed, other characteristics of wisdom writing now also clung to the Pentateuch.37

The transformations wrought by ancient biblical interpretation belong in any account of the Pentateuch’s origins. Much more, in fact, than the anonymous redactors of the hypothetical documents scholars call JE, JEP, or JEPD, the anonymous interpreters of the third and second and first centuries BCE changed utterly the whole character of the Pentateuch, as we have observed all along. No less formidable, however, has been the activity of modern biblical scholars over the last two centuries. They have succeeded, at least for those attentive to their arguments, in utterly undoing the work of those ancient interpreters and returning the Pentateuch to the disparate fragments and disiecta membra from which, by their account, it started. Has this been a good thing? Certainly not, at least not from the standpoint of those who wish to see in the Pentateuch a divinely given guidebook, a sacred and timeless text that is free of contradiction and error and speaks to people today. But good or not, modern biblical scholarship is—no less than the activity of previous interpreters and editors and authors—a fact of the Bible’s history. The question that remains is: in the light of all this, how is one to read the Pentateuch, and the rest of the Bible, today? Some elements of an answer to this question have already been introduced; I hope to present others in the chapters that follow.