North and South

1 KINGS 5–12; 17–19; 21 AND 2 KINGS 2–4 AND PSALM 29

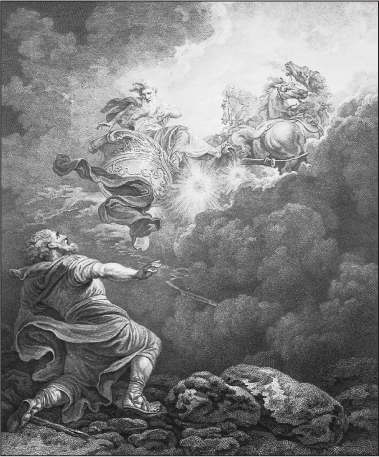

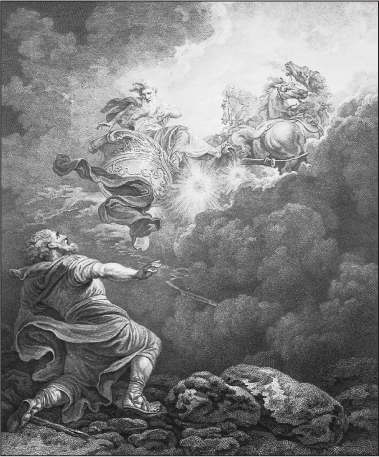

Elijah Going Up into Heaven by Philip James de Loutherbourg.

SOLOMON’S TEMPLE. THE GREAT SCHISM AND THE GOLDEN CALVES. ELIJAH AT MOUNT CARMEL. GOD VERSUS BAAL. PSALM 29. ELIJAH THE ETERNAL. THE MESHA STONE.

Solomon built the great Jerusalem temple, but his empire collapsed shortly after his son took the throne. Now there were two kingdoms, Israel in the north and Judah in the south.

One of Solomon’s great achievements was the building of a magnificent temple in Jerusalem to house, as it were, God’s presence on earth. Once he had resolved to do so, he set out to purchase the finest materials. He sent a message to his father’s old ally Hiram of Tyre, asking for the wood from the cedars from Lebanon to fashion the future temple’s furnishings (1 Kings 5:3–6). Hiram agreed. As for where in Jerusalem the temple was to stand, Solomon chose what might seem an unlikely locale, a threshing floor that had belonged to a Jebusite man, Arauna (it is to be recalled that Jerusalem was, until the time of David, a Jebusite city). The site had actually been bought from Arauna by Solomon’s father, David, who had used it to build an altar to God in time of distress (2 Sam. 24:15–25). Having fixed on this site, Solomon took the costly materials he had assembled and ordered the building of the temple to begin.

Construction took seven years to complete. The Jerusalem temple was similar to, but far bigger than, the traveling tent sanctuary that had served Israel since the time of its desert wanderings. The building consisted of three sections of increasing holiness: the innermost part, called the Holy of Holies (the equivalent of the superlative in Hebrew, hence, “holiest place”), was designed to house the Ark of the Covenant, above which God was said to be enthroned. When at last the construction had been completed,

the priests brought the ark of the covenant of the LORD to its place, in the inner sanctuary of the temple—the Holy of Holies—underneath the wings of the cherubim . . . There was nothing in the ark except the two tablets of stone that Moses had placed there at Horeb, where the LORD made a covenant with the Israelites, when they came out of the land of Egypt. And when the priests came out of the holy place, a cloud filled the house of the LORD, so that the priests could not stand and serve there because of the cloud; for the glory of the LORD filled the house of the LORD. Then Solomon said, “The LORD had said that He would dwell in a thick cloud. But now I have built You a lofty house, a place where You may dwell forever.”

The Jerusalem temple was to remain the focus of Israel’s worship for a thousand years. This is, when one considers it, an extraordinary fact. Seemingly endless generations of hereditary priests (kohanim) and Levites served there; kings, prophets, and ordinary people trooped to its precincts for century after century to demonstrate their fealty to God. There was one interruption. Destroyed by the Babylonians in 586 BCE, Jerusalem’s rugged old sanctuary lay in ruins as its people went into exile; it was rebuilt, however, almost exactly seventy years later by the Jews who returned to their land after the Babylonian Empire fell. This rebuilt structure then survived for many centuries more, until it too was destroyed by a foreign army, that of the Romans, in 70 CE. Ever since, and even today, Jews have prayed at the foot of the Temple Mount, hoping for the time when the great Jerusalem sanctuary will once again rise on or near its original spot.

Although the Temple Mount on which it was built has not been excavated by archaeologists (principally because of Muslim objections to any digging on the site, since it currently houses the al-Aqsa mosque and the Dome of the Rock), scholars have little doubt about the accuracy of the temple’s overall plan as outlined in 1 Kings 6. Actually, it is rather like a number of ancient temples that have been excavated elsewhere in the ancient Near East, particularly the temple at ‘Ein Dara‘ in Syria.1 But this very resemblance once again raises the question—disturbing for traditional Jews and Christians—of just how different Israel’s religion was from that of its neighbors. Certainly the layout of the Jerusalem temple and the nature (and even the names) of the types of sacrifices offered there have parallels elsewhere in greater Canaan and beyond; so do the priestly officials, the laws of temple purity, temple hymns and prayers, and other details from the Bible.

Indeed, some scholars have suggested that the Bible’s account of where the temple was built conceals another such connection. Saying the site had been a threshing floor before David bought it sounds rather odd. True, a threshing floor was a public space2 that would certainly be large enough to house a temple. But as everyone in biblical times knew, a threshing floor had little to suggest its aptness for such a use; it was generally considered a public nuisance, since the chaff scattered by the process of threshing grain would blow all over.3 Asserting that that is what the site had been used for before David bought it may thus have been intended to scotch any rumor that it had ever served as a sacred spot before (cf. Jacob’s “chancing” upon Bethel, Gen. 28:11). The truth, some scholars suspect, may have been quite the opposite: Solomon’s temple was built quite intentionally on a site that had always been considered sacred, one that had been used by the Jebusites for worshiping their gods before David conquered their city.4

If Solomon’s building projects and other grandiose schemes sorely taxed the public treasury, his son Rehoboam was apparently not clever enough to try to make things better. In the manner of many rulers new to the throne, he mistakenly thought the best answer to any sign of discontent among his subjects was to act tough. Thus, when Jeroboam, leader of the northern tribes, came to Rehoboam with a complaint, the young king chose the wrong course of action:

Jeroboam and all the assembly of Israel came and said to Rehoboam, “Your father made our yoke hard. Lighten this hard labor of your father’s and the heavy yoke that he set on us; then we will serve you.” He said to them, “Go away for three days and come back to me.” So the people went away.

King Rehoboam then sought the advice of the elders who had personally served his father, Solomon, while he was still alive, saying, “What is your advice for me to answer these people?” They answered him, “If, for now, you give in to these people and bow to their will, responding positively to their request and exempting them [from the duty of forced labor] when you speak with them,5 then they will bow to your will ever afterwards.” But he disregarded the advice that the elders gave him, and sought instead the advice of the young men who had grown up with him and were now his personal attendants. He asked them, “What do you advise that we answer the people who are saying to me, ‘Lighten the yoke that your father set on us’?” The young men who had grown up with him said to him, “This is what you should say to the people who said to you, ‘Your father made our yoke heavy, but you must lighten it for us’; you should say to them, ‘My little finger is thicker than my father’s loins. My father put a heavy yoke on you? I will make your yoke even heavier. My father punished you with whips? I will punish you with scorpions.’”

Jeroboam and all the people came to Rehoboam on the third day, since the king had said, “Come back to me on the third day.” The king answered the people harshly, disregarding the advice that the elders had given him, and answered them instead with the words that the young men had advised: “My father put a heavy yoke on you? I will make your yoke even heavier. My father punished you with whips? I will punish you with scorpions.” . . .

When all of Israel realized that the king would not listen to them, the people said to the king, “What share do we have in David? We have no inheritance in the son of Jesse. To your tents,85 O Israel! Look now to your own house, O David.”

So Israel went away to their tents.

Thus, it would appear, the great empire put together by Rehoboam’s grandfather David split in two because of one faulty bit of advice. The bigger, northern part became the Kingdom of Israel, ruled by Jeroboam, while the southern part became the Kingdom of Judah.

As we have seen, however, modern scholars are somewhat skeptical about just how united the United Monarchy was, even at the very height of its success. If David had, as many scholars suppose, taken over rule of the northern tribes by force, their cooperation with him and his son Solomon could have been only an iffy thing at best. So long as it served their interest to remain in league with the south, they did so. Once it became clear that the high taxes and other costs would continue without any noticeable improvement in their lot, their course became clear. “You can do what you want with your kingdom,” they said to Rehoboam; “we’re going to rule ourselves.” Still, however rickety their union may have been to begin with, the open split between Israel and Judah weakened both and ultimately left them exposed to the depredations of outsiders.846

The Sin of Jeroboam

The Bible sometimes refers to the “sin of Jeroboam” (1 Kings 13:34; 14:16; and frequently thereafter), but, interestingly, this phrase does not refer to the northerners’ secession that he led. Instead, it refers to one of his first acts as king. Surveying his new kingdom,

Jeroboam said to himself, “This kingdom might still go back to the house of David [that is, rejoin Rehoboam’s southern kingdom]. For, if people keep going up to offer sacrifices in the house of the LORD at Jerusalem, the people’s hearts may turn again to their [former] master, King Rehoboam of Judah; then they will kill me and return to King Rehoboam of Judah.” So, after consultations, the king made two golden calves. He said to them [the people], “You have gone up to Jerusalem long enough. These are your gods, O Israel, who brought you up out of the land of Egypt.” He set up one of them in Bethel, and the other he put in Dan. And this thing became a sin, for the people went to worship before the one at Bethel and before the other as far as Dan.

The great “sin of Jeroboam,” according to the Bible, was his commissioning these two golden calves as cultic objects for the temples at Dan and Bethel. Surely, bowing down to a golden calf is just what got Israel into trouble at Mount Sinai (Exodus 32)—and yet here they were, doing it again! So the prophet Hosea intoned against the “calf of Samaria” (Hos. 8:5–6) as a cause of God’s anger against the northerners: “For it is from Israel, an artisan made it; it is not God” (8:6). And indeed, the sins of Jeroboam were, according to the Deuteronomistic History, what ultimately led God to have Assyria conquer the Kingdom of Israel and send its people into exile forever (2 Kings 17:21–23).

Once again, however, modern scholars see a somewhat different reality underlying the Bible’s words. To begin with, there could have been no problem with the northern kingdom boycotting the Jerusalem temple in favor of temples at Dan and Bethel; according to scholars since de Wette, the idea of having one single, central temple in Jerusalem to serve the whole country did not exist until the time of Josiah, more than two centuries after Jeroboam. Before that, all Israelites worshiped at a host of local temples and “high places,” and no one saw anything wrong with this practice. Indeed, both Dan (Judges 18) and Bethel (Genesis 28; Judg. 20:26–28) appear to have been centers of worship with their own temples long before Jeroboam came along.

As for the golden calves, many scholars have argued that there was nothing more idolatrous about them than the cherubim that Solomon is said to have installed on either side of the Ark of the Covenant (1 Kings 6:23–28). (Indeed, God Himself is said to have instructed Moses to make such cherubim for the desert tabernacle, Exod. 25:17–20.) These great, winged, mythic creatures dominated the Holy of Holies: God was said to be enthroned on their outstretched wings above the ark, from which spot He would be in contact with Israel (Exod. 25:22; Psalm 80:1; etc.). Thus, scholars say, all that Jeroboam did was substitute one type of iconographic throne for another, the golden calves for the cherubim. In so doing, Jeroboam probably was not even inventing some entirely new iconography; both types of divine thrones had probably been in existence at different sites in the country prior to the secession of the northern tribes.7

As we have also seen, scholars are skeptical about the account of Aaron’s sin in making the Golden Calf (Exodus 32); the words he is reported to have said, “These are your gods, O Israel, who brought you up out of the land of Egypt,” turn out to be the very words spoken by Jeroboam in the passage just cited. The whole narrative of Exodus 32 is thus, these scholars say, a polemic designed to retroject the sin of Jeroboam back to the time of Aaron. What really happened, they say, is this: first came the secession and Jeroboam’s endorsement of the golden bull iconography, a perfectly normal sort of divine throne; then came the Deuteronomistic historian’s misrepresentation of this throne iconography as an actual object of worship (“These are your gods, O Israel”); last of all, these same words and deeds came to be attributed to Aaron in Exodus 32.

Whether these scholarly hypotheses are right or not, it is interesting to observe how the northern secession and the “sin of Jeroboam” have been used since the Reformation in Protestant-Catholic polemics. One of the Reformers’ early claims was that the Catholic Church was guilty of falling back “from the living God to dumme and dead idoles”8—that is to say, bowing down to statues of Mary, Jesus, and other figures. This was, they said, a violation of the second of the Ten Commandments and a return to the golden calf and the sin of Jeroboam. Roman Catholics countered that the real Jeroboam was Martin Luther—that the Protestant withdrawal from the church was a secession every bit as grave as the northern Israelites’ and that the results would be equally disastrous. Catholics cited with approval the words of Irenaeus, “Those who rend the unity of the Church receive the Divine chastisement awarded to Jeroboam; they must all be avoided” (Against the Heresies iv, 26). “Not at all,” retorted the Protestants: “the ‘sin of Jeroboam’ was not secession but bowing down to statues—and that’s one of the reasons why we left the church in the first place.”

Nowadays, such polemics have largely ceased. Yet one might not be wrong to hear, in today’s scholarly insistence that Jeroboam’s secession was only natural and that even his golden calves were not really idolatrous, the faint echo of the early Protestant apologetic. If so, this may serve somewhat obliquely as another example of the persistence of the Four Assumptions among even the most hardheaded modern researchers—specifically Assumption 2, the belief that Scripture’s account of the ancient past contains a lesson for today.

Elijah the Prophet

After recounting the split that separated the kingdoms of Judah and Israel, the Bible’s focus does not (as one might have expected) turn exclusively to events in the south. The books of 1 and 2 Kings recount subsequent events in the north, starting with the power struggles that followed Jeroboam’s death (1 Kings 14:20; 15:16–16:14) and continuing with the rise of Omri to the throne of Israel and the succession of Omri’s son Ahab. This was a particularly significant moment—not because of Ahab but because of the man who caused him so much trouble, Elijah the Tishbite.9

Elijah was a prophet and a miracle worker, feeding the hungry and bringing a dead child back to life (1 Kings 17). One would think that such a man would be universally revered, and yet King Ahab saw him as an enemy of the state, since Elijah led a campaign against the (royally sanctioned) “prophets of Baal,” who urged the people to worship this deity alongside of, or instead of, the LORD. No wonder, then, that Ahab did not extend a friendly greeting to Elijah when he ran into him:

When Ahab saw Elijah, Ahab said to him, “Is it you, you troublemaker of Israel?” He answered, “I am not the one who has troubled Israel—it is you, you and your father’s house, because you have forsaken the commandments of the LORD and followed the Baals.”

Baal is written in the plural here (ha-be‘alim, “the Baals”), probably in reference to different local cults of the great Canaanite storm god.87 As far as Ahab was concerned—and, if numerous archaeologists and biblical scholars are right, a great many ordinary Israelites as well—there was nothing wrong with worshiping Baal. Some scholars have even suggested that Baal and the God YHWH were worshiped together, in tandem or syncretistically, as the northern kingdom’s divine patron(s).10 But Elijah would have none of that. As he later says of himself, he is “exceedingly zealous” (some translations read “jealous”) on the LORD’s behalf (1 Kings 19:14)—in other words, he will not tolerate anyone worshiping Baal alongside of the LORD. He therefore issues a challenge to Ahab:

“Summon all of Israel to join me at Mount Carmel, along with the four hundred fifty prophets of Baal and the four hundred prophets of [the goddess] Asherah, who eat at [Queen] Jezebel’s table.” So Ahab sent word to all the Israelites and assembled the prophets at Mount Carmel. Elijah then approached all the people and said, “How long will you keep hopping [like birds] from one bough to the other? If the LORD is God, then follow Him. But if it is Baal, then follow him.” The people did not answer him a word. Then Elijah said to the people, “I am the only prophet of the LORD left;86 but Baal’s prophets number four hundred fifty. Let two bulls be brought to us and let them choose one bull for themselves and cut it into pieces and lay it on the wood—but do not let it be set on fire. Meanwhile, I will prepare the other bull and lay it on the wood without setting it on fire. Then you call on the name of your god and I will call on the name of the LORD, and the god who answers by fire is indeed God.” All the people cried out, “Very good!”

Elijah had challenged the prophets of Baal on, as it were, their own home court. After all, as the storm god, Baal was in charge of lightning—indeed, a lightning bolt was one of his iconographic weapons.11 Who better than Baal could send fire down from heaven to set his prophets’ bull ablaze?

So they [the prophets of Baal] took the bull that was given to them and prepared it and called on the name of Baal from morning until noon, shouting, “O Baal, answer us!” But there was not a sound, and no one answered. They kept hopping around the altar that they had made. When it got to be noon, Elijah made fun of them, saying, “Yell louder! He may be a god, but still . . . Perhaps he’s in conference, or maybe he has gone off to relieve himself somewhere—or else he might be on a trip, or fast asleep. Maybe he needs to be woken up.” They kept calling out loud and, as was their custom, they cut themselves with swords and lances until the blood gushed out over them. Even after noon had passed, they kept gyrating like [ecstatic] prophets until it was time for the [afternoon] meal offering, but still there was not a sound; no one answered or heeded [them].

Elijah said to all the people, “Come forward,” and all the people came forward. Then he fixed the altar of the LORD that had been damaged: Elijah took twelve stones—corresponding to the number of the tribes of the sons of Jacob, to whom the word of the LORD had come, saying, “Israel shall be your name”—and with the stones he built an altar in the name of the LORD. Then he made a trench around the altar, large enough to contain two measures of seed. He arranged the wood [on the altar] and cut the bull into pieces and laid it on top of the wood. Then he said, “Fill four jars with water and pour them out onto the burnt offering and onto the wood.” Then he said, “Do it again,” and they did it a second time. “Do it again,” he said, and they did it a third time, so that the water ran all around the altar and also filled the trench with water.

When it was time for the meal offering, the prophet Elijah came forward and said, “O LORD, God of Abraham, Isaac, and Israel, let it be known this day that You are God in Israel, that I am Your servant, and that I have done all these things at Your bidding. Answer me, O LORD, answer me, so that this people may know that You, O LORD, are God, and that You have turned their hearts back.” Then the fire of the LORD came down and consumed the burnt offering, the wood, the stones, and the dust, and even licked up the water that was in the trench. When all the people saw it, they fell on their faces and said, “The LORD is God; the LORD is God.”

The people’s answer was no doubt clear at the time, but nowadays it seems somewhat ambiguous. Some scholars think it should be rendered “The LORD is the God”—that is, the only deity that counts, or our only deity henceforth;12 it might even be rendered (remembering that the word ’elohim is formally a plural) “The LORD is the gods,” that is, He covers all the functions normally fulfilled by El, Baal, Astarte, and the other gods of Canaan.13

However understood, this narrative presents scholars with an important snapshot in the development of Israel’s religion. Presumably, ancient Israelites had continued for some time to worship many gods, whether or not that practice was officially sanctioned. To be sure, worshiping the God uniquely connected to the people of Israel must have enjoyed some prestige in both north and south. After all, He was uniquely “ours,” while the other gods were also worshiped by non-Israelites; as time went on, such gods must increasingly have been seen as “theirs.” Still, did that require worshiping the LORD to the exclusion of all other gods? If scholars are right, Israel’s God, at least at the beginning, had no association with fertility or the life-giving rains; He seems (as we have seen) to have been connected more to the waging of war. So, in time of drought, when rain might mean the difference between life and death, what sense did it make to worship the LORD alone? Who would forbear to heap Baal’s altar high with offerings in the hope of steering some storm clouds toward the parched fields? Yet this is precisely Elijah’s message: either Baal or the LORD, but not both. Indeed, the name Elijah means in Hebrew “My God is the LORD.”

And so, in this important confrontation at Mount Carmel, Israel is portrayed as ultimately taking its stand for the exclusive devotion to its one God (monolatry). In order for such a position to make any sense at all, one must be convinced that that one God will be able to help out in a drought just as effectively as Baal—hence the significance of Elijah bringing down the fire from heaven. The real import of “The LORD is God; the LORD is God” is that worshiping any other god is unnecessary: the LORD can bring the rain and ripen the grain and protect His people in every other way. Soon, He will be the only God in town.

Psalm 29

Scholars see a similar mentality underlying one of the Bible’s most famous psalms:

Give the LORD, O sons of the mighty, give the LORD glory and strength.

Give the LORD His own name’s glory, bow down to the LORD in holy splendor.

Listen!14 The LORD is over the waters; the glorious God is thundering, the LORD is over the deep.

Listen! The LORD is in strength! Listen! The LORD is in splendor!

Listen! The LORD is shattering cedars, the LORD shatters the cedars of Lebanon.

He makes Lebanon skip like a calf, Sirion like a young wild ox.

Listen! The LORD shoots forth sparks. Listen! The LORD makes the wilderness shake, the LORD shakes the wilderness of Kadesh.

Listen! The LORD makes the oak trees quiver as He strips the forest bare; and in His temple all say, “Glory!”

The LORD is enthroned above the flood, and the LORD will continue, forever king.

May the LORD give strength to His people, may the LORD bless His people with peace.

Psalm 29

The psalm seems to describe God’s arrival amidst a storm coming in off the sea. First He is “over the waters,” “thundering . . . over the deep”; then the storm hits land, “shattering the cedars” and making the whole earth tremble. Certainly this is a fearsome spectacle; “sparks” (lightning) shoot forth from the clouds as He arrives, and the storm’s ferocious winds strip the forest bare. But with His arrival comes the precious rain of which Canaan never seems to have enough.

After scholars came to know the literature of biblical Israel’s northern neighbor Ugarit, this psalm took on a new look. To put it bluntly, Psalm 29 seemed to many like a cheap knockoff of an originally northern Canaanite hymn, in which the name of Baal had simply been scratched out and replaced with the name of Israel’s national deity.15 Thus, the psalm opens with a summons to the “sons of the mighty” (benei ’elim) to praise the LORD. But to scholars, the phrase benei ’elim suggested the cognate phrase (bn ’ilm) found at Ugarit; there, the “sons of the mighty” are other, minor gods less powerful than Baal. If this is what these same words mean in Hebrew, then the opening lines of this psalm would seem to be calling on the lesser gods to give glory to the chief or most powerful deity, the LORD. Needless to say, such an opening would not sit very well with later Israelite monotheism, but it might indeed be the sort of thing that ninth-century Israelites could unreflectively take over from a hymn originally composed to honor Baal.16 The geographic location evoked in the mention of the mountain range “Lebanon” as well as of “Sirion” (Mount Hermon) places us squarely in northern Canaan. To be sure, this is not nearly as far north as Ugarit, but it is on the very northern edge of the Kingdom of Israel—by all accounts, Baal country in the ninth century (1 Kings 18–19). Given this background, the psalm’s whole presentation of Israel’s God thundering forth out of rain clouds and making the wilderness tremble was likewise seen by scholars as strikingly reminiscent of the descriptions of Baal in Ugaritic poetry:

So now may Baal enrich with his rain, may he enrich with rich water in a downpour.

And may he give forth his voice in the clouds, may he flash lightning-bolts to the earth . . .

Baal opens a break in the clouds, Baal gives forth his holy voice;

Baal gives forth the utte[rance?] of his [li?]ps, his ho[ly?] voice conv[ulses?] the earth . . .

The high places of the Ear[th] shake.17

Other scholars read the same evidence slightly differently, however. They believe it would be more accurate to view this psalm not as a bowdlerized Baal hymn, but as a northern Israelite polemic, and one that fits rather well with the story of Elijah on Mount Carmel. In both cases, the God of Israel is being pointedly portrayed in Baal’s traditional garb—rain clouds, lightning shooting down from the sky, supernal power. Wasn’t the point of Psalm 29 to say to northern Israelites—just as Elijah had in his challenge on Mount Carmel—“You don’t need Baal anymore”?

The Still, Small Voice

The same message seems to be embodied in the episode that follows Elijah’s defeat of Baal’s prophets. Actually, he not only defeated them on Mount Carmel, he also had them killed: “Elijah said to [the people], ‘Seize the prophets of Baal; do not let one of them escape.’ So they seized them, and Elijah brought them down to the River Kishon, where he killed them” (1 Kings 18:40).

Not surprisingly, this did not sit well with the royal family, and particularly not with Jezebel, King Ahab’s wife. She was a patron of Baal and Asherah worship and an out-and-out enemy of prophets who advocated worshiping the LORD (18:4), including, of course, Elijah. When she heard that Elijah had killed off the prophets of Baal, she considerately sent him a message informing him that she intended to do the same to him (19:2). Elijah immediately fled to the south.

He got up, and ate and drank; then he went in the strength of that food forty days and forty nights to Horeb, the mountain of God. At that place he came to a cave, and spent the night there.

Then the word of the LORD came to him, saying, “What are you doing here, Elijah?” He answered, “I have been very zealous for the LORD, the God of hosts; for the Israelites have forsaken your covenant, thrown down your altars, and killed your prophets with the sword. I alone am left, and they are seeking my life, to take it away.” He said, “Go out and stand on the mountain before the LORD.”

And behold, the LORD passed by and a great, strong wind split the mountains and broke rocks into pieces before the LORD. The LORD was [or is] not in the wind. And after the wind a shaking; the LORD was [or is] not in the shaking. And after the shaking a fire; the LORD was [or is] not in the fire. And after the fire was the sound of the thinnest stillness. When Elijah heard it, he wrapped his face in his mantle and went out and stood at the entrance of the cave. Then there came a voice to him that said, “What are you doing here, Elijah?”

The phrase rendered above as “the sound of the thinnest stillness” was translated in the King James Version as “a still, small voice,” and as such it has enjoyed a rich afterlife in the English language. The poet John Greenleaf Whittier (1807–92) composed a famous hymn, “Dear Lord and Father of Mankind,” which concludes:

Breathe through the heats of our desire

Thy coolness and Thy balm;

let sense be dumb, let flesh retire;

speak through the earthquake, wind, and fire,

O still, small voice of calm.

Perhaps emblematic of the transition from the nineteenth century in America to the mid-twentieth is the somewhat pantheistic use of the same phrase in a song performed to wide approval by the pop artist Perry Como:

A still small voice will speak to you one day.

A still small voice will call to you and say,

“I am the earth, the sky, the brightest star on high,

the tallest tree, the smallest drop of dew.”

A still small voice one day will say to you!18

Endless sermons and devotional tracts have also been entitled “The Still, Small Voice.” Rather early on, this phrase became identified with the promptings of a person’s own conscience, and it is principally in that sense that it is used today—hence the 1918 film And a Still, Small Voice, directed by Bert Bracken, a “tale of crime and redemption” in which the criminal, tormented by conscience, gives himself up, reforms, and ends up marrying the girl of his dreams. But it may also be relevant to observe that “the still, small voice” has served of late as the name of a guide to Buddhist meditation techniques; a technological innovation in the telecommunications industry; an editorial about tax alternatives in the Eugene (Oregon) Register Guard; a biography of the novelist Zona Gale; two collections of poetry; a CD album by the guitarist Paul Jackson Jr.; four or five novels; “a psychic’s guide to awakening intuition”; and an article on the difficulties attendant to the identification of WIMPs, weakly interacting massive particles, which have been drifting around the universe ever since the Big Bang.

Needless to say, none of these is quite the sense in which the phrase was used in 1 Kings. In fact, scholars connect its use in the passage cited to the theme already seen, Baal’s displacement by the God of Israel, save that here, the very idea of the deity’s immanence in the natural world is challenged. Thus, the LORD is not in the great, strong wind (like Baal), nor, like Baal, is He immanent in the storm winds that shake the earth or the fire that comes down from heaven. What this passage seems to reject is the deity’s identification with any of the pyrotechnics of the natural world (including, perhaps pointedly, those that were said to have accompanied the first great revelation of the LORD at Sinai/Horeb).19 Instead, the true God’s voice is beyond the natural world, it is “the sound of the thinnest stillness.”20

Elijah the Immortal

Elijah is a classically northern (Israelite) sort of prophet. A Moses-like worker of miracles, he splits the Jordan in two (2 Kings 2:8; cf. Exod. 14:21) and makes abundant food and drink from a short supply (1 Kings 17:10–16; cf. Exod. 16:4–18). Also like Moses, he survives for forty days and forty nights without food or drink (1 Kings 19:8; cf. Deut. 9:9). He can also make it rain or make it stop (1 Kings 17:1) and bring a dead boy back to life (17:17–24); he is fed by the ravens (17:6) or by angels (19:5). An outsider, he is for the most part an out-and-out enemy of the king (Ahab in fact calls him “my enemy” in 1 Kings 21:20) whose duties include reprimanding royal improprieties21 (such as in the case of Naboth, who was executed on a trumped up charge so that the royal family could take possession of Naboth’s vineyard, 1 Kings 21).

Such things, scholars say, were altogether typical of the expected repertoire of prophets in the north,22 so it is no accident that some of the same things were done by Elijah’s equally northern understudy, Elisha. Elisha, who is also an enemy of the king (2 Kings 2:13–14), provides abundant potable water from a single bowl of salt water (2:19–22; cf. Exod. 15:25) and abundant oil from a single cruse (4:1–7). Like Elijah, Elisha also knows how to revive a boy from the dead (4:18–37).23 He also feeds a hundred people with a small number of barley cakes (4:42–44), cures an Aramean leper (2 Kings 5; cf. Exod. 4:6–7; Num. 12:10–16), and levitates an axe handle from the Jordan (6:1–7). Some of these items are likewise reminiscent of the things related of a later Galilean, Jesus of Nazareth.24 As we will see, they stand somewhat in contrast to the actions of the prophets of the southern kingdom, Judah, who are less given to working miracles and more focused on prophetic visions and lengthy speeches.

According to the biblical account, Elijah’s string of miracles was not brought to an end by his death; in fact, he did not die. Instead, the prophet ascended bodily into heaven:

When they had crossed [the Jordan], Elijah said to Elisha, “Tell me what I may do for you, before I am taken from you.” Elisha said, “Please let me inherit a double share of your spirit.” He responded, “You have asked a hard thing; yet, if you see me as I am being taken from you, it will be granted you; if not, it will not.” As they continued walking and talking, a chariot of fire and horses of fire separated the two of them, and Elijah ascended in a whirlwind into heaven. Elisha kept watching and crying out, “Father, father! The chariots of Israel and its horsemen!” But when he [Elisha] could no longer see him, he grasped his own clothes and tore them in two pieces.

Modern scholars tend to shrug their shoulders at the accounts of such miracles or, putting on them the best face possible, describe them as “hagiography.”25 But for ancient readers the story of Elijah’s heavenly ascent was extremely important. If he went up to heaven and was not heard from again, it certainly seemed possible to them that he was still up there, waiting to be ordered back down to earth.

Thus developed the motif of “Elijah the Immortal.” Its earliest reflex is to be found within the Hebrew Bible itself at the very end of the book of Malachi. There, this late biblical prophet announces in God’s name:

Remember the teaching of My servant Moses, the statutes and ordinances that I commanded him at Horeb for all Israel. For I will send you the prophet Elijah before the arrival of the great and terrible day of the LORD. He will turn the hearts of fathers to their children and the hearts of children to their fathers, so that when I come I will not strike the land with destruction.

1 Mal. 4:4–5 (Hebrew, 3:23–24)

According to Malachi, Elijah not only had been spared death but was waiting around in heaven so as to be able to fulfill this important mission before the events of the end-time. Ben Sira, the second-century BCE Jewish sage, described Elijah in these terms:

You were taken on high by a whirlwind, by fiery legions to heaven.

Ready, it is written, for the time to put [divine] wrath to rest, before the day of the LORD,

to turn back the hearts of fathers to their children and to reestablish the tribes of Israel.

Ben Sira basically restates what Malachi had said, although he does go beyond the prophet’s words in two particulars. According to Ben Sira (but not Malachi), Elijah will actually stave off disaster in general, putting the divine wrath to rest, whereas all Malachi seemed to say was that Elijah would prevent the coming destruction from “striking the land.” Beyond this, it is noteworthy that, according to Ben Sira, Elijah’s return will inaugurate the restoration of the long-lost ten tribes.26

Elijah was still eagerly awaited two centuries later, in the time of Jesus. Quite naturally, some people thought that John the Baptist might be Elijah:

This is the testimony given by John [the Baptist. They asked him:] “Who are you?” He confessed and did not deny it, but confessed, “I am not the Messiah.” And they asked him, “What then? Are you Elijah?” He said, “I am not.”

The same was apparently thought of Jesus:

Jesus went on with his disciples to the villages of Caesarea Philippi; and on the way he asked his disciples, “Who do people say that I am?” And they answered him, “John the Baptist [who had been killed]; and others, Elijah; and still others, one of the prophets.”

Mark 8:27–28 (cf. 6:15; 9:11–13; 15:35–36)

Part of Elijah’s biblical afterlife, so to speak, derived from his identification with Phinehas, the zealous priest who lived in the time of Moses and had been among the Israelites during their desert wanderings. Phinehas therefore seemed to ancient readers to have had an extraordinarily long existence—he is mentioned long after the exodus and the entry into Canaan, at the end of the period of the Judges (Judg. 20:28). In fact, the Bible contains no mention of his death,27 a surprising circumstance for such a distinguished and aged person. Out of this developed the supposition that Phinehas never did die: he and Elijah were one and the same person. On consideration, their identification did not seem so far-fetched: after all, both Elijah and Phinehas were described in the Bible (twice each) as being “very zealous/jealous” for God—the only two biblical figures so described (Num. 25:11, 13; 1 Kings 19:10, 14). Surely this had been intended as a clue. It thus seemed possible to ancient interpreters that, having last been glimpsed in the period of the Judges, the zealous/jealous (and immortal) Phinehas simply lay low for a few hundred years, only to reappear as the ninth-century prophet. When he did reappear, the Bible curiously never said who Elijah’s father was, he was just “Elijah the Tishbite” from Gilead. This would be the equivalent nowadays of introducing a historical figure by his first name only, “Then Tom came to Washington from Virginia.” Was this not further confirmation that “Elijah” (meaning “My God is the LORD”) was actually a kind of nom de guerre for the embattled, immortal zealot? Little wonder, then, that Elijah, having fought against the forces of Baal in the ninth century, had ascended into heaven to wait for his next appearance—or that people in later times might think that John the Baptist, or even Jesus, was really Elijah returned to earth.28

Such, in short, was Elijah’s image for generations and centuries of Bible readers—he was Ahab’s enemy, the man who challenged the prophets of Baal and miraculously caused the fire to come down from heaven, the one to whom God revealed Himself in the “still, small voice,” the prophet who ascended bodily into heaven and who is there still, waiting for the day to come when he will announce the arrival (or return) of the Messiah.

The Mesha Stone

Many of the archaeological finds of the last century have seemed to disagree with one or another detail of the biblical record, casting doubt on the historicity of (among other things) the story of the exodus, the forty-year period of desert wanderings, or the conquest narrative. But sometimes archaeologists turn up things that startlingly confirm the biblical record.

Chapter 3 of 2 Kings recounts a horrific event that ended a battle in which the combined forces of the Kingdoms of Israel and Judah had been pitted against Moab, their neighbor across the Jordan River. Until that time, Moab had been a compliant vassal of Israel:

Now King Mesha of Moab was a sheep breeder, who used to deliver to the king of Israel [as tribute] one hundred thousand lambs and the wool of one hundred thousand rams. But when Ahab died, the king of Moab rebelled against the king of Israel. So King Jehoram marched out of Samaria [the Israelite capital] at that time and mustered all Israel. As he went he sent word to King Jehoshaphat of Judah, “The king of Moab has rebelled against me; will you go with me to battle against Moab?” He answered, “I will; I am with you, my people are your people, my horses are your horses.”

Having concluded this alliance with his erstwhile countrymen, the Kingdom of Judah, Jehoram decides to consult the prophet Elisha to make sure that victory will indeed be his. But Elisha is no great fan of Jehoram; Jehoram’s father was none other than Ahab, the sworn enemy of Elisha’s master, Elijah. So at first Elisha refuses to predict the battle’s outcome: “What do I have to do with you?” he says to the king. “Go to your father’s prophets or to your mother’s,” that is, the prophets of Baal. But Jehoram insists (“No; it is the LORD who has summoned us,” he says), so Elisha agrees to give an oracle: victory will indeed be Jehoram’s.

In the course of the battle, however, King Mesha makes a desperate move:

When the king of Moab saw that the battle was going against him, he took with him seven hundred swordsmen to break through, opposite the king of Edom; but they could not. Then he took his firstborn son who was to succeed him, and offered him as a burnt offering on the wall. And great wrath came upon Israel, so they withdrew from him and returned to their own land.

2 Kings 3:26–27

Repugnant as it may seem to us, this human sacrifice seems to have saved the day:29 Israel retreated and Moab was left an independent country.

Excavating in what is now Jordan in the summer of 1868, a German missionary stationed in Jerusalem, F. A. Klein, came upon a large rectangular basalt stone, rounded at the top, that had been inscribed with what looked like Hebrew words. This was not the alphabet used for Hebrew today, but was quite similar to the paleo-Hebrew script used in biblical times. Anyone trained in that script would have no difficulty in reading what the clearly incised letters were saying:

I am Mesha, son of Chemosh[yat?]30 King of Moab, the Dibonite. My father was king over Moab for thirty years and I was king after my father. I made this high place for Chemosh88 in Qar![]() oh, . . . for he saved me from all the kings, and he allowed me to see the downfall of all my foes.

oh, . . . for he saved me from all the kings, and he allowed me to see the downfall of all my foes.

Amazingly enough, the inscription turned out to be a first-person account by the very same Mesha mentioned in 2 Kings 3, and in the inscription he reviewed the history of his country’s relations with Israel as well as recounting his victorious campaign.31

Omri [was] the king of Israel and he oppressed Moab for many days, for Chemosh was angry with his land. And his son89 succeeded him, and he said: I too shall oppress Moab. In my time he said this; but I got to see his downfall and that of his house, and Israel was lost forever.

The inscription then goes on to describe at length some of Mesha’s other victories and building projects.

Apart from its mention of some of the names and other details found in the biblical account, the inscription is noteworthy for its presentation of Chemosh, a god whose “anger” with his land results in oppression by foreigners. Chemosh also tells Mesha when the time is right to attack (“And Chemosh said to me: ‘Go take Nebo against Israel,’” line 14). These same two things were said of Israel’s God here and there in the Bible and feature as prominent motifs in the book of Judges.