Ezekiel

EZEKIEL 1–3; 18; 22; 37–39

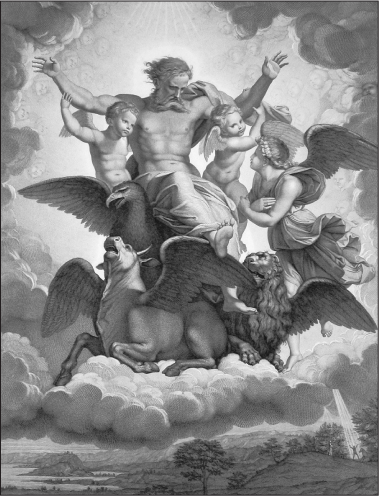

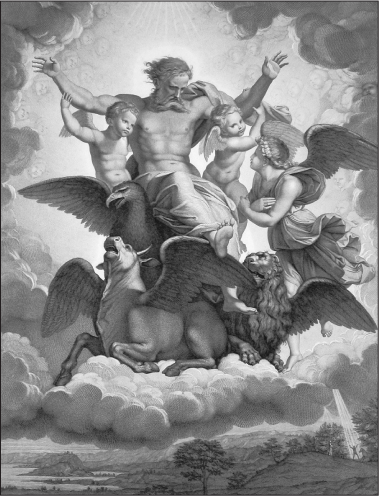

The Vision of Ezekiel by Raphael.

OTHERWORLDLINESS. “BLESSED FROM HIS PLACE.” FIGURES ON THE CHARIOTS. THE CALL OF EZEKIEL. THE LAWS OF LEVITICUS. VICARIOUS PUNISHMENT. DRY BONES. A DIFFERENT KIND OF PROPHECY.

Ezekiel saw the divine throne chariot as he stood among the Judean exiles in Babylon. What was Israel’s God doing there?

Ezekiel son of Buzi was a younger contemporary of Jeremiah and, like Jeremiah, a priest and prophet. But there the resemblance ends. What stands out with Jeremiah is his human side; he is often passionate and always utterly engaged with his fellow Judeans. “Hurry up,” he tells them, “Change your ways! Otherwise, all will be lost.” Ezekiel is quite the opposite; otherworldly and oddly detached, he is the recipient of strange visions and symbolic messages. His prophesying may have physically taken place in Babylon during the exile, but the precise circumstances are often left vague. He seems to jump inexplicably from place to place, and much of the time he appears to be addressing no one in particular. True, his admonitions can be bitingly personal on occasion. But mostly, his gaze is turned upward, fixed on the divine part of the divine-human axis. As for what people will do with his message, he often sounds oddly indifferent: “I’ve done my part.”

In Ezekiel’s prophecies, two words in particular stand out. The first is ben-adam, the term by which God most frequently addresses Ezekiel. Literally, it means “son of man,” but it might be better translated as “little man” or “mere mortal.”112 No phrase could better bespeak an individual’s smallness in the presence of God’s overwhelming and powerful being.1 The other word, less often noticed, is ya‘an, “whereas” or “since”—usually followed by a “therefore.” Like any verbal tic, this one is significant. It is a formal-sounding word (one might even say, a lawyer’s kind of word). It seems to say that everything is orderly and everything has an identifiable cause: even the chaos of Jerusalem’s collapse and the subsequent exile were not random events, but the product of a single, powerful, divine will.

Ezekiel’s most striking vision is also the first in the book.

In the thirtieth year, in the fourth month, on the fifth day of the month, as I was among the exiles by the river Chebar, the heavens opened and I saw visions of God. (On the fifth day of the month—it was the fifth year of the exile of King Jehoiachin—the word of the LORD came to the priest Ezekiel son of Buzi, in the land of the Chaldeans [Babylonians] by the river Chebar; and the hand of the LORD was on him there.)

I looked and saw a wind-storm coming in from the north: a huge cloud with flashing fire and a glow all around; and coming out of the fire, something that was the color of amber. And coming out of it [also] were the figures of four creatures. This is what they looked like: They seemed like humans, but each one had four faces; their legs went down straight, but their feet were calves’ feet that sparkled like polished bronze. They had human arms under their wings on all four sides, and the wings and faces on the four sides were connected, one wing to the other, and they [the creatures] would not turn when they moved, but each could proceed in the direction of [any one of] its faces.

Their faces were like this: all four had a human face [in front] and a lion’s face on the right side, and the face of an ox on the left side, and an eagle’s face [in back]. Their faces and their wings were separated on top. Each [face] had the two connected wings and two [others] that covered their bodies; and each could proceed in the direction of [any one of] its faces, wherever the spirit might be to go, there they would go, and they would not turn when they moved . . .

As I was watching the creatures, I noticed that there was a wheel on the ground next to each of the four-faced creatures. The wheels seemed to be made out of something like beryl, and all four looked the same: they appeared to be made in such a way that there was one wheel within another. And when they moved, each could move in the direction of any of its four quadrants without having to be turned as they moved. Their rims were high and most frightening, since the rims of all four were covered over with eyes all around. When the creatures moved, the wheels would move along with them; and when the creatures were lifted up above the earth, the wheels would be lifted too. Wherever the spirit might be to go, there they would go, and the wheels would be lifted up next to them, since the creature’s spirit was in the wheels. When they [the creatures] would move, [the wheels] would move too, and when these stopped, so would they; and when these were lifted above the earth, the wheels too would be lifted next to them, since the creature’s spirit was in the wheels.

Above the heads of the creatures was some sort of an expanse, with the fearsome gleam of crystal stretching above their heads . . . And above the expanse over their heads was something like a throne, as if of sapphire; and seated above this likeness of a throne was what seemed to be a human form . . . There was a glow all around Him, like the look of a rainbow in a cloud on a rainy day; that was what the glow looked like all around; this was the appearance of the semblance of the LORD’s glory. When I saw this, I fell on my face, and then I heard a voice speaking.

What did Ezekiel see? It seems to have been nothing less than God’s own heavenly throne, the same throne that Isaiah had seen when God called him to be His messenger (Isaiah 6). But here the description is strikingly detailed: the throne depicted here was apparently movable, arriving in a cloud amidst a wind storm and supported by four creatures with wings and multiple faces, wheels and wheels-within-wheels—what did it all mean? From ancient times, readers have sensed a power, and a danger, in this passage. It has thus been, on the one hand, the point of departure for generations of mystics, who have scrutinized it in the hope of retracing Ezekiel’s steps and finding their own path to the direct encounter with God’s very being.2 Precisely for that reason, however, Jewish law forbade the public teaching of Ezekiel’s vision, and tradition even limited its study in private to the company of mature adults.3 Its esoteric character notwithstanding, the passage has long been a central part of Ezekiel’s image in popular culture. Many Americans remember the words of the old Negro spiritual:

Ezekiel saw a wheel a-turning,

Way in the middle of the air,

A wheel within a wheel a-turning,

Way in the middle of the air . . .

Having seen the very foundations of God’s heavenly throne, Ezekiel is then formally commissioned as a prophet (Ezek. 1:28–3:11). At that point, his great vision ends—but with a sentence that proved as puzzling to ancient readers as all the rest:

Then a spirit lifted me up and I heard behind me a great roaring sound, “Blessed is the LORD’s glory from His place.”

Ezek. 3:12

Who said these words that Ezekiel heard, and what for?

Even today, many of the details of Ezekiel’s vision are as mysterious to interpreters as they were two and a half millennia ago. More than one modern reader has identified Ezekiel’s vision as an encounter with aliens from outer space or a drug-induced hallucination, but the truth is that no one can say for sure what the prophet was describing or how his vision came about. This has not, however, stopped people from trying—starting with the Bible’s most ancient interpreters.

Blessed from His Place

One important focus of interest for ancient interpreters was the last sentence cited, “Blessed is the LORD’s glory from His (or its) place.” Interpreters were drawn to it for the same reason that they were drawn to Isaiah’s “Holy, holy, holy is the LORD of Hosts” (Isa. 6:3). They were eager to establish prayers and praises of God that would please Him, and they looked to the Bible for help in supplying just the right words. From the Isaiah passage it appeared that the angels—presumably on God’s instructions—said “Holy, holy, holy” as they surrounded the divine throne; thus, one thing that humans could do was say these same words down here on earth, joining the angels, as it were, in God’s favorite form of praise. By the same logic, “Blessed is the LORD’s glory from His place” ought also to be said, since, according to Ezekiel, these words, too, were uttered around the divine throne. Indeed, these two biblical passages seemed to go together, since they both spoke specifically of God’s “glory.”4

It was not long, therefore, before ancient interpreters integrated the two into a single picture of the angels praising God in a kind of heavenly liturgy:

Let us sanctify and praise You in keeping with the melodious song of the choir of heavenly seraphim, who triple their consecration to You, as was written through your prophet, “And each called to the other and said: Holy, holy, holy is the LORD of Hosts, the whole earth is full of His glory.” Across from them they sing praises with the words, “Blessed is the LORD’s glory from His place.”

Kedushah (Jewish daily prayer)

In reciting these two biblical verses together, in other words, human beings were simply repeating the two things that Scripture explicitly reported being said around God’s heavenly throne. No less than “Holy, holy, holy,” Ezekiel’s “Blessed is the LORD’s glory from His place” became a fixed part of Jewish prayers and has remained so to the present day.

But how exactly did the two verses fit together? As the above passage makes explicit (in the words “across from them”), it seemed to interpreters that there must have been two opposite choirs, one composed of seraphim in Isaiah 6, the other of the wheel angels (ofanim) described by Ezekiel. Not only were these two different groups, but they seemed to be praising in two quite different modes. In Isaiah, it will be recalled, the seraphim turn “one to the other,” a gesture that suggested coordination and, hence, musical harmony. In Ezekiel, by contrast, the words come with “a great roaring sound.” Interpreters thus saw these as contrasting sounds:

They [the seraphim] lovingly give permission one to another to sanctify their Creator in gentleness of spirit, in language pure and sacred melody, all sing out in harmonious awe, “Holy, holy, holy is the LORD of Hosts, the whole earth is full of His glory.”

Thereupon, the wheel-angels and holy creatures with a great roaring sound lift themselves up across from the seraphim and say to them in contrast: “Blessed is the LORD’s glory from His place.”

Yotser ’Or (Jewish morning prayer)

But what did the words “Blessed is the LORD’s glory from His place” actually mean? This was far from clear. In the context of the above understanding it seemed to some as if this sentence might be some kind of a response to the preceding assertion of the seraphim, “the whole earth is full of His glory.” That is, even if the whole world is full of God’s glory, one might still think that there exists some specific place from which that glory emanates:

And each called to the other and said: “Holy, holy, holy is the LORD of Hosts, the whole earth is full of His glory.” [Indeed,] the world is full of His glory. [Still,] His servants [the angels] ask each other, “Where is the place [that is, the source] of His glory?” It is in response to these that they say the “Blessed” [part, namely]: “Blessed is the LORD’s glory from His place.”

Musaf Kedushah

In this imagined context, “Blessed is the LORD’s glory from His place” sounds a bit like a rebuke: the place of God’s glory is His business alone—it is, after all, His place. If so, the implication would be that even inquiring angels are not to delve into such mysteries.5

A Movable Throne

In trying to understand the opening vision of the book of Ezekiel, modern scholars, as so often, seek to view things in terms of their historical setting—and, in this case, to connect that setting to the person of Ezekiel himself. Ezekiel was not just a priest, they point out, but most likely one of the elite Zadokites. This priestly clan traced its lineage back to Zadok, whom Solomon had made his sole high priest after banishing Abiathar (1 Kings 2:27). Thereafter, it seems, the Zadokites ran the Jerusalem temple continuously, not just in Solomon’s time, but for the next four hundred years, until the Babylonian exile. If Ezekiel was indeed a Zadokite, not only would that fit, scholars say, with what is known of his life history and with the closing vision of his book (chapters 40–48, focused on the Zadokites), but it would help explain his attitude toward the Jerusalem temple. Jeremiah may have seen the Babylonians’ destruction of the temple as an event comparable to the earlier loss of the temple at Shiloh, but for Ezekiel, any such comparison was profoundly irrelevant and perhaps sacrilegious. The Jerusalem temple was, for Ezekiel, God’s sole legitimate dwelling on earth; its destruction was thus nothing short of a cataclysm. How could He have allowed those bloodstained Babylonian boots to tramp unopposed in the very place of His earthly presence, the Holy of Holies?

Ezekiel’s apparent answer is that God was no longer there at the time. He had left, ascending into the heavens on a movable throne chariot—the same chariot that Ezekiel sees in chapter 1—long before the actual Babylonian siege of Jerusalem began. (See also Ezekiel 10 and 11, which, in a flashback, describe God’s departure from the temple.) That is why this God-bearing chariot could be seen by Ezekiel in Babylon, where he was “among the exiles by the river Chebar . . . in the fifth year of the exile of King Jehoiachin” (Ezek. 1:1–2), that is, in 593 BCE. Presumably, what happened was that Ezekiel, as a member of the elite, had been among the eight thousand Jews who were marched to Babylon by Nebuchadnezzar after his initial incursion into Jerusalem in 598 BCE. At some point thereafter, God abandoned His temple and ascended into heaven on His chariot, following this first wave of Jewish exiles to Babylon. Indeed, it seems likely to scholars that the wheels mentioned in Ezekiel’s vision are precisely intended as an expression of mobility: God does not simply sit on a throne (as in Isaiah 6 and elsewhere), but on a throne chariot, one that moves through the air supported from underneath by four vaguely human-shaped, mythical beasts.

The Four Faces

Not long ago, archaeologists came upon an ancient pagan temple in ‘Ein Dara‘, in modern Syria. The temple, which was perhaps built in the eighth century BCE, has shed some light on one aspect of Ezekiel’s vision of God’s throne chariot. In the excavated lower court, archaeologists unearthed the figures of a number of hybrid creatures—human bodies topped with the nonhuman heads of an eagle or a lion—plus an ox’s head and body and a human figure with a human head.6 These, it will be noticed, are precisely the same four creatures mentioned by Ezekiel in his vision, “all four had a human face [in front] and a lion’s face on the right side, and the face of an ox on the left side, and an eagle’s face [in back].” That these same four, and no others, should appear at ‘Ein Dara‘ seems to scholars unlikely to be the product of coincidence. In addition, scholars have noted that these creatures all have upraised hands, as if they were supporting or carrying something—just as the four hybrid creatures in Ezekiel’s vision were supporting God’s throne chariot. How these similar elements might have entered into Ezekiel’s vision is something of a mystery; as best anyone knows, he never was at ‘Ein Dara‘, and in any case, the temple had been destroyed by the time of his birth. It was apparent—to these scholars, in any case—what Ezekiel saw was neither pure fancy nor extraterrestrial reality, but a vision rooted in a long-established ancient Near Eastern iconography (and not one exclusively associated with Israel’s God!).

The words spoken at the end of Ezekiel’s vision, “Blessed is the LORD’s glory from His place,” have also been investigated by modern scholars. In context, they seem somewhat problematic. To begin with, these words are not introduced as if they were a direct quote: Ezekiel does not say that someone said them, or even that they were said. On the contrary, the text simply says that he heard a “great roaring sound: ‘Blessed is the LORD’s glory from His place.’” This juxtaposition seems oddly abrupt.

Long ago it was remarked that the letters corresponding to our K and M are easily confused in the ancient (paleo-Hebrew) script of Ezekiel’s time.

Such a confusion, scholars say, is probably what gave rise to “Blessed is the LORD’s glory from His place.” For, if one replaces the K at the end of the first Hebrew word in this sentence with an M, it no longer means “blessed” (barukh) but “as it rose” (berum).7 In context, this would seem to work much better. What Ezekiel now says is that, after having had this vision of the heavenly chariot, “a spirit lifted me up and I heard behind me a great roaring sound, as the LORD’s glory rose up from its place.” What he heard was the roaring of the heavenly chariot as it departed; no words were spoken at all.

Thus, if scholars are right, then it would seem that the picture embodied in the Jewish prayers seen earlier—two choirs of angels, one singing, “Holy, holy, holy,” the other intoning, “Blessed is the LORD’s glory from His place”—really has nothing to do with Ezekiel’s original vision. It derives from a scribe’s confusion of two similarly shaped letters. Such a possibility raises yet another painful question for traditional faith, since these prayers are still said every day in synagogues around the world. But how can modern Jews continue to praise God with these words if they are simply the result of an ancient copyist’s error?

God’s “Glory”

It should be clear, scholars also point out, that Ezekiel does not seem to share Deuteronomy’s sense of God’s remoteness and relative abstractness. For Ezekiel, as with the priestly texts of the Pentateuch, God has a definite, bodylike presence—precisely the sort of presence that would go with the whole idea of a temple, that is, a “house” in which a deity dwells. Thus, they say, Ezekiel would never ask the question posed by God in Deutero-Isaiah:

The heavens are My throne, and the earth is but My little footstool.

Where could you build a house for Me? In what place might My abode be?

The clear implication is: nowhere. God is much too huge to have any true abode on earth. (Similarly, as we have seen, in Deuteronomy the temple is the place where “I cause My name to dwell.”) But for Ezekiel and the other priests, to say this was to deny the whole enterprise to which they devoted their lives, the serving of the actual being of God inside His holy temple through animal sacrifices, incense offerings, and other acts of devotion.

That is why, scholars say, Ezekiel speaks of God’s glory. The word is somewhat misleading, since in English it often refers to visual phenomena. This sense is not entirely unknown in Hebrew either (see Isa. 60:1), but the Hebrew word kabod is most often associated with substance or weight (kabed means to “be heavy”). It is thus more appropriate to understand this word as designating some physical presence or manifestation of God—and so it is used, scholars say, specifically in priestly texts. Hence, Moses asks of God in Exod. 33:18 (a passage generally held to be of priestly origin), “Show me Your glory”—that is, let me actually catch sight of You. As was seen earlier, this is hardly a foreign way of conceiving of God in much of the biblical period, although it was eventually replaced by something closer to our current way of thinking of Him. Indeed, scholars note that Ezekiel’s description is not fully anthropomorphic: on the throne chariot, for example, he sees only “what seemed to be a human form,” and God’s glory is hidden by a surrounding “glow.” Still, this glory or physical presence moves from one place to another, from the Jerusalem temple into the skies over Babylon, and Ezekiel no doubt believed that, at some future point, the glory would return to Mount Zion.

Like other prophets, Ezekiel is summoned to act as God’s messenger, but in this, too, there is something profoundly odd about what the Bible reports:

He said to me: “Little man, stand up on your feet so I can speak to you. Then a spirit entered me while He was talking and stood me up on my feet, and I heard someone speaking to me, saying to me: Little man! I am sending you to the people of Israel, to the rebellious ones who have rebelled against Me; they and their fathers have disobeyed Me all along, to this very day. In fact, the sons—those to whom I am sending you—are impudent and stubborn-hearted. So say to them: ‘Thus says the LORD God . . .’ Then, whether they heed or refuse to heed (for they are a rebellious house), at least they will know that they had a prophet in their midst.

“As for you, little man, do not be afraid of them, and do not be fearful of their words, though thistles and thorns surround you and you sit down among scorpions. Do not be afraid of their words, and do not lose your courage, for they are a rebellious house. But you will speak My words to them whether they heed or refuse to heed; for they are a rebellious house.

“And you, little man, listen now to what I am telling you. Don’t be rebellious like that rebellious house; open your mouth and eat what I am giving you.”

As I watched, a hand was stretched out to me holding a written scroll. He opened it in front of me; it was written on both the front side and on the back, and written on it were words of lamentation and mourning and woe.

Then He said to me: “Little man, eat what is given to you; eat this scroll, and then go, speak to the house of Israel.” So I opened my mouth, and He gave me the scroll to eat. He said to me: “Little man, eat this scroll that I give you and fill your stomach with it.” So I ate it; and in my mouth it turned as sweet as honey.

God’s summons to Ezekiel is meant to sound a bit like that of a mother to her young son: “Be a good boy, eat this!” In this case, however, the one being so urged has cause for hesitation: the “food” in question looks doubly inedible. First of all, it consists of a rolled-up scroll, and if that isn’t unappetizing enough, it is written on both sides with words of mourning and woe. Yet Ezekiel is quite the opposite of the rebellious Israelites to whom God is sending him. He obediently takes the scroll and starts to chew, and to his astonishment, it turns out to be as sweet as honey. The message embodied in this vision seems to be: although being My prophet does not look like it will be a happy mission, since what you will have to say is principally “lamentation and mourning and woe,” try it nonetheless! Then you will see that, however sour the words you speak, being My emissary is indeed sweet.

In one respect, scholars say, this call narrative seems specifically crafted to evoke two others examined previously. Isaiah’s mouth was touched by the burning coals, thereby becoming a worthy receptacle of God’s words. Later, God actually put His words directly into Jeremiah’s mouth. Now Ezekiel takes an entire scroll of God’s words into his mouth and eats it. Indeed, for modern scholars, it seems as if the third prophet was quite consciously looking over his shoulder at the other two and, as it were, seeking to go them one better.8 (In addition, scholars have noted that the central image in this passage seems likewise to evoke Jeremiah’s previously cited assertion, “Your words were found and I devoured them,” Jer. 15:16). But altogether characteristic of Ezekiel is the striking “disconnect” here between God’s message (sour words) and the messenger (to whom they taste sweet). What counts, Ezekiel says again and again in his book, is bringing God’s words to the people; the fact that those words presage doom, or that the “rebellious house” to whom they are addressed will not care to heed them, seems to matter little or not at all to him. Elsewhere God tells him, “I have made you a sentinel for the house of Israel” (Ezek. 3:17). Sentinel is just right. His job is thus simply to report on what he sees, announcing the approaching doom like a city’s watchman standing on the ramparts. Once he has discharged this duty, the sentinel is not to be responsible for what people do with his message: if they disobey, it is at their peril. And peril was indeed approaching: the Babylonians’ military power seemed simply overwhelming. One way or another, it was simply a matter of time.

Ezekiel the Priest

As a member of the Zadokite clan of priests that ran the Jerusalem temple, Ezekiel naturally would have had a great interest in all the concerns that functioning priests had—ritual purity, maintenance of the temple, the correct offering of animal sacrifices, and so forth. But what has struck scholars is that these so-called ritual concerns are, in this prophet’s world (as in some of the priestly parts of the Pentateuch), close neighbors of the most fundamental ethical norms. And so Ezekiel rebukes the people for their mistreatment of strangers or failure to honor their parents, but in the same breath he condemns them for ritual matters like not keeping the sabbath properly or contracting impurity through forbidden sexual unions. This might seem incongruous, but what strikes modern readers as the juxtaposition of two sets of quite different concerns was, for Ezekiel, the whole point. In the priestly world, a sin does not just go away or get forgotten.9 It stuck to the sinner, who was condemned to carry it around everywhere until forgiveness could be obtained—just as cultic impurity was thought to cling to a person’s body until he or she had undergone purification. Indeed, in its various aspects, guilt for wrongdoing is treated in priestly texts in a way altogether analogous to ritual impurity.10

Such a mingling of ritual and ethical prohibitions is a prominent feature, scholars have noted, of the Holiness Code of Leviticus 17–26. At times it seems as if Ezekiel is consciously thinking of sections of this code as he rebukes the people. Compare, for example:

Father and mother are treated by you with contempt; among you, the stranger is oppressed, the widow and the orphan are taken advantage of. . . . One man commits abomination with his neighbor’s wife, another man defiles his daughter-in-law with lewdness. . . .

For every man who treats his father or his mother with contempt shall be put to death . . . A man who commits adultery with a married woman, with his neighbor’s wife, shall be put to death—both the adulterer and the adulteress. . . . And a man who sleeps with his daughter-in-law, the two of them shall be put to death.

It is hardly surprising that Ezekiel should have known these prohibitions from the Holiness Code; he was, after all, a priest and these laws were the particular patrimony of the priesthood. Still, a further point has struck scholars with regard to Ezekiel 22 and similar passages. The prophet looks out at his contemporaries and sees . . . Scripture! That is, he rebukes his fellow citizens “by the book,” echoing the exact language found in the Pentateuch. In this, some scholars say—as indeed in Ezekiel’s account of his own call—we are witnessing the growing influence of an already established body of sacred texts. These texts, whenever they originated, were not understood to belong to some other age and circumstances. For Ezekiel and others, they were addressed to present reality, they told us what to do. Israel did not yet have a Bible as such, but at least for some Israelites, the holy words written down of old contained a message brimming with significance for their own day.

Deferred Punishment

Ezekiel’s words of reproof were sometimes bitter: taking up an old image, he compared the people of Israel to a beautiful woman who had “played the harlot” (Ezek. 16:15), abandoning her true husband, God, to lie down with other gods. Had she forgotten all that He had done for her in the past? Israel’s current punishment was thus deserved—and it was not, as some people maintained, a punishment incurred because of the sins of an earlier generation:

The word of the LORD came to me: Why should you cite that [old] proverb in connection with the land of Israel, “When parents eat sour grapes, it’s the children’s teeth that hurt [that is, we all pay for our parents’ sins]?” As I live, says the Lord GOD, this proverb shall no more be cited by you in Israel. The lives of everyone belong to Me, the parent’s as much as the child’s is mine: [therefore,] the one who sins is the one who will die. If a man is righteous and does what is right and just—if he does not eat upon the mountains or lift up his eyes to the idols of the house of Israel, does not defile his neighbor’s wife or approach a woman during her menstrual period; if he does not oppress anyone, but restores to the debtor his pledge; if he has not acquired anything through theft, but gives his food to the hungry and covers the naked with a garment; if he does not take advance or accrued interest, abstains from wrongdoing [in court], dealing fairly [in disputes] between one man and another; [in short,] if he follows My statutes, and is careful to observe My ordinances, acting faithfully—then such a one is [judged] righteous; he shall surely live, says the Lord GOD.

This passage is remarkable in part for the reason already seen: it is full of allusions to Scripture. Thus, eating “on the mountains” apparently refers to eating things sacrificed on the “high places,” a practice forbidden in Deut. 12:2 and elsewhere; and lifting up one’s eyes to idols is the omnipresent sin of idolatry. The other violations are mostly word-for-word quotations from Leviticus: see Lev. 18:19–20; 19:13, 15; 25:17, 36; 26:3. Beyond this point, however, is what this passage says about the idea of vicarious or deferred punishment, that is, the notion that people are sometimes punished for the sins of others, particularly their own forebears. This was a commonplace in the ancient Near East. How better to understand the suffering of apparently innocent people than to suppose that they were being punished for something that their parents, or grandparents, or still more remote ancestors, had done? It is apparently in this sense as well that God is described as “visiting the punishment of the parents on the children to the third and the fourth generation of those who reject Me” (Exod. 20:5). Indeed, the Deuteronomistic historian’s idea that it was the “sin of Manasseh” (2 Kings 21:10–16), Josiah’s grandfather, that caused the fall of Jerusalem in the generation after Josiah likewise presumes the idea of vicarious punishment (although Deut. 24:16 specifically rejected vicarious punishment, at least in human jurisprudence).

What Ezekiel asserts here is quite the opposite. It is not a matter of the parents “eating sour grapes,” racking up a big tab of sins, and their sons paying the bill (see also Jer. 31:30).11 God holds each person responsible for his or her own actions. Indeed, even the person who sins is not necessarily doomed:

But if the wicked person turns away from all the sins he has committed and keeps all My statutes and does what is right and just, he will live; he will not die. None of the transgressions he has committed will be counted against him. By virtue of the righteousness that he has done, he will live. Do I take any pleasure in the death of the wicked? says the Lord GOD. Do I not instead [take pleasure] in his turning from his ways and living?

Here truly was an important message of consolation for the exiled community—and a sharp break with an ancient conception of divine justice.

Dry Bones

The book of Ezekiel is set against the gloom of the Babylonian exile, yet it contains a dream: not only would the people one day return to Judah, but they would eventually be reunited with the long-lost northern tribes, exiled from Israel by the Assyrians some 150 years earlier. Reestablished in their ancient homeland, these tribes would join with Judah to resurrect the Davidic monarchy, and fortune would once again smile on Jacob’s progeny. This dream was announced in different ways, but perhaps none so memorably as Ezekiel’s vision of the valley of dry bones:

The hand of the LORD came upon me, and He took me out by the spirit of the LORD and put me down in the midst of a valley that was full of bones. He led me all around them; there were a great many of them across the valley, and they were very dry. He said to me, “Little man, can these bones come back to life?” and I answered, “O Lord GOD, You are the one who knows.” Then He said to me, “Prophesy over these bones, and say to them: O you dry bones, hear the word of the LORD. Thus says the Lord GOD to these bones: I will put breath into you so that you come back to life. Then I will put sinews on you and cover you over with flesh, and then spread skin all over you, and put breath inside of you, so that you come back to life. Then you will know that I am the LORD.”

I started prophesying as I had been told, but while I was prophesying, there was a sound, a whirring, and the bones came toward each other, one bone connecting another. Then I noticed that they had sinews on them, and flesh had formed on them, and skin spread over them; but there still was no breath inside them. Then He said to me, “Prophesy to the breath [or wind].113 Prophesy, little man, and say to the breath [wind]: Thus says the Lord GOD: From the four winds, O breath, come and breathe upon these, who were killed, so that they come back to life.” I prophesied as He told me to do, and the breath went into them, and they came back to life and stood on their feet, a huge multitude.

Then He said to me, “Little man, these bones are the whole house of Israel. They are saying, ‘Our bones are dried up, and our hope is lost; we are cut off completely.’ So prophesy, and say to them: Thus says the Lord GOD: I will open your graves and lift you out of your graves, my people; and I will take you back to the land of Israel. And you will realize, my people, when I open your graves and lift you out of your graves, that I am the LORD. Then I will put My spirit inside you, and you will come back to life, and I will put you back on your own land. Then you will know that it is I, the LORD, who have spoken [that is, promised] and carried out,” says the LORD.

When Ezekiel saw a valley full of bones, dried out by the sun and seeming beyond all hope of revivification, he understood the message: the bones represent the “whole house of Israel,” those northern tribes that had been deported. They might appear dead now, and yet, God could and would bring them back to life.12 North and south would once again be united, and a mighty empire would raise its head as in days of old. Indeed, it was not, Ezekiel said, just a matter of physical resuscitation, but of a changed spirit. Like the book of Jeremiah, Ezekiel said that God would make a new covenant with His people, and things would return to what they were before:

My servant David [that is, one of his descendants] will rule over them, and they will all have one shepherd. They will follow My rules and they will carefully carry out My laws. They will settle in the land that I gave to My servant Jacob, and in which your ancestors lived. They and their children and their children’s children will live there forever, and My servant David will be their prince forever. Then I will make a covenant of peace with them. It will be an eternal covenant with them, and I will bless them and make them numerous, and I will set down My sanctuary in their midst forever. My dwelling place will be with theirs, and I will be their God, and they will be My people.

But it was never to be. Wherever the northern tribes had ended up, they never again returned to the Samarian hills. To this day, their fate is quite unknown.

What happens to a person after death? The question has fascinated people from earliest times, and the peoples of the ancient Near East were no exception. The Egyptians had an elaborate picture of the realm of the dead, and, in a different way, so did the Mesopotamians. But ancient Israel, at least judging by the Hebrew Bible, had only a rather vague view of the subject. People were frequently said to “go down to Sheol,” the underworld, but not much seems to have gone on once they got there. “The dead do not praise the LORD, none who go down to the Pit” (Ps. 115:17). Still, some biblical texts imply that the dead were not altogether dead. Saul summoned up Samuel from the grave, and biblical laws prohibiting the offering of sacrifices to or for the dead, necromancy, and similar practices all seem to indicate that a lively “cult of the dead” existed at times in Israel and environs. Archaeological evidence from the eastern Mediterranean has offered some confirmation for these conclusions.13

In late- and postbiblical times, the subject came to be discussed more openly, and in somewhat different terms. Both Judaism and Christianity came to affirm the belief in the resurrection of the dead, and, predictably, both turned to the Bible for confirmation. The Pentateuch, however, seemed to be silent on this matter—and its silence was, particularly for Jews, puzzling and disturbing. But if no programmatic statement could be found in that highly authoritative book, there was at least the evidence of Ezekiel. His vision of the valley of dry bones may have been, as we have seen, essentially concerned with the “resurrection” of the northern tribes and their eventual reunion with Judah. But for later readers, it acquired a quite different meaning. It was now a favorite example of the Hebrew Bible’s doctrine of the resurrection of the dead:

The mother of seven sons [said]: “[Your father] read to you about Abel slain by Cain, and Isaac who was offered as a burnt offering, and about Joseph in prison . . . He reminded you of the scripture of Isaiah, which says, ‘Even though you go through the fire, the flame shall not consume you.’ He sang to you songs of the psalmist David, who said, ‘Many are the afflictions of the righteous.’ He recounted to you Solomon’s proverb, ‘There is a tree of life for those who do his will.’ He confirmed the query of Ezekiel, ‘Shall these dry bones live?’ For he did not forget to teach you the song that Moses taught, which says, ‘I kill and I make alive: this is your life and the length of your days.’”14

Then the heavenly one will give souls and breath and voice to the dead,

and bones fastened with all kinds of joinings . . . flesh and sinews

and veins and skin about the flesh, and the former hairs.

Bodies of humans, made solid in heavenly manner,

breathing and set in motion, will be raised in a single day.

Sibylline Oracles II 221–26

For the prophets have foretold his two comings: one, which has already taken place, as a dishonored and suffering man; the second when, according to prophecy, he will raise the bodies of all men who have ever lived, and will clothe those among the worthy with immortality, and will send the wicked . . . into everlasting fire with evil devils. And we can demonstrate these things to come have likewise been foretold. This is what was spoken through Ezekiel the prophet: “Joint shall be joined to joint, and bone to bone, and flesh shall grow again” and “every knee shall bow to the LORD, and every tongue shall confess him” [Ezek. 37:7–8; Isa. 45:24]

Justin Martyr, First Apology 52

Apart from its inherent interest, the transformation of Ezekiel’s words attested in these passages written by ancient interpreters is a good example of how texts can change their meaning over time. Ezekiel was talking about a fairly immediate and altogether political matter: can those northern tribes be brought back to Israel and reestablish the mighty empire of David? But for later ages, that question receded. Ezekiel’s new message was that God could, and would, resurrect the dead.

Ezekiel in Modern Scholarship

Modern scholars’ questioning of the authorship of the book of Ezekiel has not been as far-reaching or consequential as that of the book of Isaiah.15 Much of Ezekiel, they say, stems from a single period, the Babylonian exile, indeed, from a single hand. This does not mean, however, that that hand was Ezekiel’s. As with Jeremiah, some scholars believe that the work of committing the original prophet’s words to writing might well have been done by someone else, a proposition supported here and there by passages that appear to have been glossed or otherwise refashioned. So, while it is basically the book of Ezekiel, it is the prophet’s words as reported and, at times, reformulated and supplemented by someone else.16

The book as a whole shows clear signs of having been organized by topic. Its first part opens with Ezekiel’s vision of the throne chariot and his summons by God. Then we find him in the company of the Jewish exiles in the Chebar valley, where he denounces the sins that will lead to destruction (chapters 4–9); then he describes in detail the departure of God’s glory from Jerusalem in the throne chariot (10–11), thus ending this first section through a reconnection to the opening chapter. The next section of the book, chapters 12–24, consists of divine condemnations of Judah, often in the form of vivid metaphorical depictions: Jerusalem is a faithless and ungrateful woman (chapter 16); two great eagles beset little Judah (chapter 17); a huge sword is whetted and readied for the slaughter (chapter 21); and so forth. Chapters 25–32 are condemnations of foreign nations, one by one (but mostly focusing on Tyre, the coastal city-kingdom to Israel’s north), while chapters 33–39 are taken up with prophecies of Israel’s restoration. The book’s last chapters, 40–48, deal exclusively with the rebuilding of the Jerusalem temple and all that will go on there. Some scholars have expressed doubt that the restoration prophecies or the temple visions have any connection with the historic Ezekiel; perhaps, they say, these chapters are the work of a fellow Zadokite priest who wrote at the very end of the exile, or even after it was over.

Of particular interest in the latter part of the book is Ezekiel’s vision of a certain foreign king named Gog and his kingdom, Magog (a name that seems to mean “Gog’s place”). No such kingdom existed, and if there ever was a Gog, Ezekiel probably knew little more of him than his name. (A certain Gyges ruled the area that is today western Turkey about a century before Ezekiel’s birth, and his name, scholars say, may have provided the inspiration for this vision.) What is striking about this vision is that it seems to contain elements characteristic of a kind of writing that was to flourish later on in the postexilic period, a kind referred to loosely as “apocalyptic.” This sort of writing is not given to easy definition (in fact, some scholars have suggested retiring apocalyptic as a genre classification, since it seems too vague and covers too broad a range of texts). In general, however, “apocalyptic” has been used to describe revelations (in Greek, apokalupsis) of some future, climactic series of events that will set things aright again or bring history to some dramatic climax (sometimes referred to as the eschaton or “end-time”).

Gog appears to be a kind of generalized, one-size-fits-all tyrant, perhaps connected with figures in earlier Israelite prophecies, since he is called the one “of whom I spoke earlier through my servants the prophets” (Ezek. 38:17). Gog will band together with Israel’s hostile neighbors in a mythic battle, one that will end in Israel’s triumph. “On that day, I will give Gog a burial place in Israel,” God promises (Ezek. 39:11); he and all his army will be interred, a process that will take seven months to complete. Then the land will be purified, and “I will set My glory before the nations . . . and the house of Israel will know that I am the LORD their God, from that day on” (Ezek. 39:21–22).

Then I will restore Jacob to its place, and have mercy on the whole house of Israel; and I will act zealously for My holy name. They will forget their shame, and all the treachery they practiced against Me when they were dwelling securely in their own land, with no one to make them afraid. But when I bring them back from the peoples and gather them up from the lands of their enemies, then I will be sanctified by them in the sight of many nations. And they will realize that I am the LORD their God, both when I sent them into exile among the nations and when I gathered them back into their own land. I will leave none of them behind, and I will never again hide My face from them, for I will pour out My spirit upon the house of Israel, says the Lord GOD.

But this, too, was not to be. No Gog ever materialized, at least no great-but-defeated foe such as that described in Ezekiel. Instead, when the Babylonian domination ended, it did so because of another foreign power, the Persians, who overcame it. As for the Jews, they did indeed return to their homeland, but as a subject people once again. This only whetted their appetite for some dramatic conclusion to their confusing history.