Text and Exposition

OVERVIEW

Two types of response are possible for the modern reader who first glances at ch. 1 of the book of Numbers. One is ennui, a sense of boredom. First the reader is told about the command of the Lord for Moses and Aaron to take a military census of Israel. This sounds rather unpromising. Then the reader is assaulted by a list of unfamiliar, compound Hebrew names (1:5–15), names that are a threat to any but the most self-assured Scripture reader. As though this were not enough, the reader then finds twelve two-verse paragraphs that are identical in wording except for the name of the tribe and the sum of its people (1:20–43).

Worse, the paragraphs all center on numbers. The first chapter of the book teams with numbers; everywhere we turn we read number after number. No wonder the book has come down to us in English with a singularly uninspiring title! Who but a mathematician could rise with joy to a book called “Numbers”?

But these same features may bring another response, especially for the reader who approaches tasks with curiosity. This is the response of intrigue, interest, and even wonderment. Surely the Torah was not written to bore the reader—ancient or modern! The listing of names was never meant simply to test the skills of a reader, nor could the repetitions merely have been designed to test a person’s resolve to continue reading—no matter what! There must be significance in these names, numbers, and repetition.

Further, we soon discover that the tedious repetition in ch. 1 is not unique to the book. The repetition of ch. 7 similarly seeks to undermine whatever appreciation we might try to muster up for the values underlying such repetitious language.

Thus the expectations of the modern reader in approaching this text are irrelevant to a valid evaluation of the purpose and nature of the book. As with any book of Scripture—indeed, any book of intrinsic merit—the book of Numbers must be read on its own grounds. The Bible sets its own agenda; the materials of Scripture take their own shape. That its interests and methods may be different from our own is beside the point. If this book is to be received by the modern reader with the integrity and demands of Scripture as a significant part of the divine outbreathing (2Ti 3:16)—the fourth portion of the Torah, the book of Moses—then we must set bias aside, avoid negative prejudgments, escape first impressions, and come to the book as it is.

The best approach toward any obtuse or “difficult” portion of Scripture is to pepper it with questions. In the case at hand we might ask: Why would the ancient sages feel it important to include the names of each tribal representative? Why was it believed impressive to list the number of men from each tribe in such a formal manner, requiring the measure of repetition as 1:20–43 presents? What are the values suggested by these repeated paragraphs? Is it possible that in this alien aesthetic form these verses of repeated phraseology are not to be regarded as tiresome at all but something of dignity, solemnity, and even beauty? Is there perhaps an impressive nature to these paragraphs that speaks of the pride of each tribe?

Indeed, the repetitions are likely instructive as to the power of God and his faithfulness to his promises. That reader who first turned his face away from these pages with disdain may have turned away from something that is intended to bring praise to God and confidence among his people. It becomes our point of view that these numbers, in their highly stylized environments, are a matter of celebration of the faithfulness of Yahweh to his covenantal people. So as we come to these numbers and words, let us come to them on their own terms to see what in them is impressive—and what in them is instructive for us.

I. THE EXPERIENCE OF THE FIRST GENERATION IN THE WILDERNESS (1:1–25:18)

OVERVIEW

An explanation is given in the Introduction (Unity and Organization) for the unusual outline this commentary presents. Following the lead of Dennis T. Olson, I see the macrostructure of the book of Numbers as a bifid of unequal parts. The two censuses (chs. 1–4, 26) are the keys to our understanding the structure of the book. The first census (chs. 1–4) concerns the first generation of the exodus community; the second census (ch. 26) focuses on the experiences of the second generation, the people to whom this book is primarily directed. The first generation of the redeemed was prepared for triumph but ended in disaster. The second generation now has an opportunity for greatness—if only the people will learn from the failures of their fathers and mothers the absolute necessity of robust faithfulness to Yahweh despite all obstacles.

A. The Preparation for the Triumphal March to the Promised Land (1:1–10:36)

OVERVIEW

The record of the experiences of the first generation is presented in two broad parts. Chapters 1–10 record the story of their preparation for triumph; chs. 11–25 follow with the sorry record of repeated acts of rebellion and unbelief, punctuated by bursts of God’s wrath and instances of his grace.

1. Setting Apart the People (1:1–10:10)

OVERVIEW

As the book as a whole presents itself as a bifid of unequal parts, so chs. 1–10 also form a bifid of unequal sections: 1:1–10:10 records the meticulous preparation of the people for their triumphal march into Canaan; 10:11–36 describes their first steps under the leadership of Moses.

a. The Census of the First Generation (1:1–4:49)

i. The muster (1:1–54)

(a) The command of the Lord (1:1–4)

1The LORD spoke to Moses in the Tent of Meeting in the Desert of Sinai on the first day of the second month of the second year after the Israelites came out of Egypt. He said: 2“Take a census of the whole Israelite community by their clans and families, listing every man by name, one by one. 3You and Aaron are to number by their divisions all the men in Israel twenty years old or more who are able to serve in the army. 4One man from each tribe, each the head of his family, is to help you.

COMMENTARY

1 Each phrase of verse 1 is significant for our study; we need to move slowly here. One of the most pervasive emphases in the book of Numbers is that Yahweh spoke to Moses, and through Moses, to Israel. From the opening words of the book (1:1) to its closing words (36:13), this concept is stated over 150 times and in more than twenty ways. One Hebrew name for the book of Numbers is waye dabbēr (“and [Yahweh] spoke”), the first word in the Hebrew text. This name is highly appropriate, given the strong emphasis on God’s revelation to Moses in Numbers.

The opening words set the stage for the chapter and, indeed, for the entire book. The phrase, “the LORD [Yahweh] spoke to Moses,” presents a point of view that will be repeated (and restated) almost to the point of tedium throughout this book. Yet it is just such a phrase that is so important to the self-attestation of the divine origin of Numbers. The phrasing announces the record of a divine disclosure of the eternal God to his servant Moses, and from Moses a faithful transmission to the people of God. This type of phrase does not satisfy our curiosity as to how Moses heard the word of God, whether as the articulated words of a human voice; a mystical inner sensation, perhaps a clearly articulated cluster of words in his mind; or some vague mental image. This phrase merely presents the source and reception of communication. Numbers 12:6–8 is the major text describing the Lord’s use of Moses as his prophet. This section will indicate something of the special manner of the divine disclosure to Moses, but the phrasing that is most characteristic merely states the most important point: Yahweh spoke to Moses.

That the subject of the verb “spoke” is Yahweh points to his initiation and, by that measure, to his grace. The fact that God speaks at all to anyone is evidence of his mercy, that he continued to speak to Moses throughout his leadership of the people of God is a mystery, and that he spoke to Moses with the intent that others would read these words throughout the centuries is a marvel. The repetition of phrases such as this throughout the Torah serves for emphasis. We are to be duly impressed with the fact that the Lord is the Great Communicator, that of his own volition he reached out to Moses to convey to him the divine word and to relate through him to the nation the divine will. Other gods are mute. Other gods are silent. Other gods are no God at all. But the God of Scripture, the Lord of covenant—Yahweh, God of Israel—speaks! What he desires more than anything else is a people who will hear him, who will take joy in obeying him, and who will bring him pleasure by their response.

The second phrase of v.1 (NIV) centers on the place of God’s speaking to Moses: “in the Tent of Meeting” (beʾōhel mô ʿēd); this phrase follows “in the Desert of Sinai” in the Hebrew construction). There are other terms and phrases used for this tent in Numbers. It is called “the tabernacle” (hammiškān; vv.50, 51) and “the tabernacle of the Testimony” (miškan hāʿēdut; vv.50, 53). The expression “the Tent of Meeting” speaks of the revelatory and communion aspect of the tent. The term “tabernacle” by itself points to the temporary and transitory nature of the tent; it was a moveable and portable shrine, specially designed for the worship of God by a people on the move. The expression “the tabernacle of the Testimony” suggests the covenantal signification of the tent; within were the symbols of the presence of the Lord among his people, his guarantees of continuing relationship.

Critical scholarship has confounded the issue by suggesting that these several terms refer to different tents, or that they are telltale pointers to different strata in the tortured path (in their view) of the composition of the Torah. But this approach is unnecessary; it seems preferable to read these several terms as correlative, stylistic variants used for effect to describe various realities of the central focus of God’s relationship with his people in the wilderness—the tent of his presence.

The more common Hebrew name for the book of Numbers is bemidbar (“In the Wilderness”), the fifth word in the Hebrew text. God spoke to Moses in the Tent of Meeting during the lengthy period that Israel spent in the Desert of Sinai. The wilderness setting is pervasive in Numbers. Recall from the introduction, “God has time, and the wilderness has sand.”

The book begins with the leadership of Israel’s following faithfully the commands of the Lord and the people’s being mustered together for war against the cities of Canaan in anticipation of a great conquest of the Land of Promise. But because of the perfidy of the people, that great event of conquest—the realization of the promise of God to the fathers and mothers of Israel—was denied for a generation. Instead, in judgment for doubt and for casting the worst possible accusations against God about their deliverance—that their “wives and children will be taken as plunder” (14:3)—the entire populace over the age of twenty would spend the rest of their natural days in the wilderness. Only Joshua and Caleb, because of their exceptional, unswerving faith in the face of their timid compatriots, would enter the land.

As it turned out, Miriam and Aaron—and even Moses—died in the wilderness. The expression “in the wilderness” is rich in its meaning and associations. It is not just descriptive of a physical feature of topography; it is also a metaphor for the experience of the people of Israel described in this book. One day their descendants would enter the land, but this book is the record of the experience of the people “in the Desert of Sinai.”

This first verse also gives a specific temporal notice for the command of God to take a census of the nation—a date that is precise and detailed: “on the first day of the second month of the second year after the Israelites came out of Egypt.” The book of Numbers begins thirteen months after the great exodus. The people had spent the previous year in the region of Mount Sinai receiving the law, erecting the tabernacle, and becoming a people. Now they were to be mustered as a military force and formed into a cohesive nation to provide the basis for an orderly march. The events of Numbers cover a period of thirty-eight years and nine or ten months, i.e., the period of Israel’s wilderness wanderings. The second month in the Hebrew calendar corresponds roughly to our April. Later, when Israel was established in Canaan, this second month would be the month of general harvest between the Feast of Firstfruits and Pentecost or Weeks, seven weeks following Passover. That Israel was being numbered during a time that later would be associated with the harvesting of crops would probably not have been lost on the later readers of this book.

This pattern of dating events from the exodus signified the centrality of the exodus in the experience of God’s people. Time would now be measured from their leaving Egypt. The wording is not unlike the Christian reckoning of time as “BC” (“Before Christ”) and “AD” (“Anno Domini,” meaning “in the Year of our Lord”). Time, for Israel, had its beginning with the exodus, just as time for the Christian has its beginning and meaning with the salvation provided in the Savior, Jesus. The exodus was God’s great act of deliverance of his people from bondage; the story of the exodus is the gospel in the OT.

Another example of dating from the exodus is found in 1 Kings 6:1, where the beginning of the building of the temple of Solomon is dated in the four-hundred-eightieth year of Israel’s exodus from Egypt. Whether this date is an exact figure (i.e., one year more than four hundred seventy-nine years) or, as is sometimes suggested, a round number suggesting twelve generations (i.e., 12 x 40—the approximation of a generation), the point is still sure: the dating of Israel’s experience with God begins with the exodus from Egypt (see Notes).

Gordon J. Wenham, 56, observes that the materials of the book of Numbers are not arranged strictly in chronological order (also, see Introduction: Unity and Organization). The descriptions of 7:1–9:15 belong to the first two weeks of the first month of the second year of the exodus (cf. Ex 40:2; Nu 9:1), whereas the census and related affairs of Numbers 1–6 begin on the first day of the second month (see, again, 1:1). The concern of the writer was thematic rather than strictly chronological; it was literary rather than pedantic. The issues of the numbering of the people and the ordering of the camp were believed to be foundational to the understanding readers would need for the stories of offerings, worship, and Passover in chs. 7–9. Moreover, as noted in the introduction, Olson has shown the book of Numbers to be a biped, each section beginning with a census (chs. 1–4; 26; see Notes). The deliberate changing of chronology of the materials of the book is a signal to the reader that chronology is not nearly as important as the fact of the census.

The dating of the exodus itself remains a deeply debated issue among biblical scholars, both moderate and conservative. (More liberal scholars—sometimes called “minimalists”—do not regard the exodus as a historical event; for them the issue is moot.) Archaeological evidence has been adduced for both an early thirteenth-century date (the “late date view”) as well as a mid-fifteenth-century date (the “early date view”). Kenneth A. Kitchen has argued ably for the thirteenth-century date (Ancient Orient and Old Testament [Downers Grove, Ill.: InterVarsity Press, 1966], 57–75; see now his Reliability, 241–74). Gleason L. Archer Jr., however, has argued vigorously for the fifteenth-century date for the exodus (see his introductory article on “The Chronology of the Old Testament” in EBC1, 1:366–67). Such a pattern would suggest that the events of the book of Numbers extended thirty-eight years into the second half of the fifteenth century BC (see Notes).

2 The Hebrew verbs śeʾû (“take”; v.2) and tipqedû (“number”; v.3; see Notes) are in the plural, indicating that Moses and Aaron were to complete this task together (see v.3, “you and Aaron”), but the primary responsibility for the task lay with Moses. The purpose of this census was to form a military roster, not a social, political, or taxation document, as some modern interpreters have suggested. There are other reasons for the census however: (1) to demonstrate to the people the extent of God’s faithfulness in fulfilling the provisions of the Abrahamic covenant in multiplying the physical descendants of Abraham (Ge 12:2; 15:5; 17:4–6; 22:17), (2) to provide a clear sense of family and clan identity for the individual, and (3) to provide the means for an orderly march of the people to their new home in Canaan.

There is a remarkable specificity in the numbering process, moving from the broadest groupings to the individual. These Hebrew phrasings are “clans,” “families,” “names,” and “every male by their heads.” This stylistic device, common in Hebrew prose, moves from the most general to the specific, thus giving a sense of the totality of a task and the enormity of carrying it out. We find the same type of approach in the words that came to Abram describing the associations he must leave as he was to set out on his journey of faith with the Lord: “your country,” “your people,” “your father’s household” (Ge 12:1; order as in the MT). Similarly, in the story of the binding of Isaac Abraham was told to take his “son,” his “only son,” whom “he loves,” “even Isaac” (Ge 22:2; order as in the MT).

3 The words of verse 3 also point clearly to the principal military purpose of the census: those males who were over the age of twenty and who were able to serve in the army. This type of phrase occurs fourteen times in ch. 1 and again in 26:2.

Readers who are bothered by the military nature of the census prefer to view it as an early experiment in sociology. The wording of the MT is so patently military in nature, however, that this escape simply does not seem to be possible. The point of the census was to prepare the armies of Israel for their triumphal war of conquest against the peoples of Canaan. In fulfillment of the promise Yahweh made to father Abraham (Ge 15:16–21), the descendants of those who went to Egypt were to return with great possessions and would then be given the land inhabited by numerous nations and ethnic groups. Evil pervaded those nations and groups; the sins of the Amorites had now reached full measure (cf. Ge 15:16). The campaign of conquest was soon to begin.

Our knowledge of the end of the story makes this a sad record to read: all the peoples who were numbered for military duty in this chapter—every one of them save only Joshua and Caleb—died without ever experiencing God’s war of conquest. It is true that some participated in the abortive engagement with the Amalekites following their rebellion against the Lord (14:44–45), but this was not a glorious war of victory. It was an ignoble rout! Victory would come only to their children, a generation removed. Hence this listing, intended by God to be a roster of soldiers, a table of heroes, a memorial of victors, became instead a memorial of those who were to die in the wilderness without ever experiencing God’s greater purpose in their lives.

There was another mustering of soldiers for war at the end of the wilderness period (ch. 26). The men in that account were entirely different persons from those listed in ch. 1. Except for Joshua and Caleb, all those in ch. 1 died in the wilderness between slavery and liberty, between cursing and blessing, between there and here, with hopes dashed and desires never fulfilled. All died in the dry, barren wilderness, though God had intended for them the enjoyment of the good life in the good land and his gracious hand. But in the new roster of Numbers 26 there was a new generation, a new beginning, a new hope. It was “the death of the old and the birth of the new” (cf. Olson’s title; see Introduction).

4 By having a representative from each tribe assist Moses and Aaron, not only would the task be made somewhat more manageable, but also all would regard the resultant count as legitimate. No tribe would have reason to suggest that it was under- or overrepresented in the census, since a worthy man from each tribe was a partner with Moses and Aaron in accomplishing the task. Election observers in our own day fill a similar role.

NOTES

1 The wording of the first verse of Numbers, when compared with the wording of the last verse (36:13), fits well with the concept that Numbers is an independent “book” within the larger collection of the fivefold book, the Pentateuch. This is a point argued well by Olson, 46–49. He also ties the book of Numbers to the ![]() (tôledôt, “generations, family histories”) formula of Genesis (cf. Ge 2:4a; 5:1; et al.; see Nu 3:1 and Notes). This wording provides the overarching structure for the entirety of the Pentateuch (Olson, 83–114; also in Dennis Olson, Numbers [Interpretation; Louisville, Ky.: John Knox, 1996], 3–7); cf. comments on 3:1).

(tôledôt, “generations, family histories”) formula of Genesis (cf. Ge 2:4a; 5:1; et al.; see Nu 3:1 and Notes). This wording provides the overarching structure for the entirety of the Pentateuch (Olson, 83–114; also in Dennis Olson, Numbers [Interpretation; Louisville, Ky.: John Knox, 1996], 3–7); cf. comments on 3:1).

![]() (leṣēʾtām mē ʾereṣ miṣrayim, “their leaving the land of Egypt”) is not simply a slogan; the miraculous departure of the people of Israel from Egypt, the exodus, is the fundamental act in their history. A recent presentation for the “early date” ca. 1446 BC (or even a bit earlier) is made by William H. Shea, “The Date of the Exodus,” in Howard and Grisanti, eds., Giving the Sense, 236–55. Conservative scholars who support the “late date” (ca. 1290 BC) include LaSor, Hubbard, and Bush, in OTS–1996, 59–60, and Kitchen, Reliability, 307–10. Conservative scholars continue to debate the dating of the exodus. The position taken in this commentary is based on the “early date” chronology. However, the greater issue these days is not when the exodus took place, but whether it ever happened. William G. Dever (What Did the Biblical Writers Know? 2001; Who Were the Early Israelites? 2003), not known as an evangelical writer, nevertheless has been in the forefront in the engagement of those scholars (sometimes called “minimalists”) who deny most of the historicity of the OT story. Recent evangelical works that challenge minimalists include those by Kitchen (Reliability) and Raymond B. Dillard and Tremper Longman III (AIOT).

(leṣēʾtām mē ʾereṣ miṣrayim, “their leaving the land of Egypt”) is not simply a slogan; the miraculous departure of the people of Israel from Egypt, the exodus, is the fundamental act in their history. A recent presentation for the “early date” ca. 1446 BC (or even a bit earlier) is made by William H. Shea, “The Date of the Exodus,” in Howard and Grisanti, eds., Giving the Sense, 236–55. Conservative scholars who support the “late date” (ca. 1290 BC) include LaSor, Hubbard, and Bush, in OTS–1996, 59–60, and Kitchen, Reliability, 307–10. Conservative scholars continue to debate the dating of the exodus. The position taken in this commentary is based on the “early date” chronology. However, the greater issue these days is not when the exodus took place, but whether it ever happened. William G. Dever (What Did the Biblical Writers Know? 2001; Who Were the Early Israelites? 2003), not known as an evangelical writer, nevertheless has been in the forefront in the engagement of those scholars (sometimes called “minimalists”) who deny most of the historicity of the OT story. Recent evangelical works that challenge minimalists include those by Kitchen (Reliability) and Raymond B. Dillard and Tremper Longman III (AIOT).

3 ![]() (tipqedû, “number”) is a use of the significant Hebrew verb

(tipqedû, “number”) is a use of the significant Hebrew verb ![]() (pāqad, “to attend to, visit, muster”; GK 7212) that at times describes Yahweh’s “visiting” his people, either in great grace (e.g., Ge 21:1) or in horrific judgment (e.g., Hos 1:4). In Numbers it is used with the idea of “passing in review, mustering, numbering.”

(pāqad, “to attend to, visit, muster”; GK 7212) that at times describes Yahweh’s “visiting” his people, either in great grace (e.g., Ge 21:1) or in horrific judgment (e.g., Hos 1:4). In Numbers it is used with the idea of “passing in review, mustering, numbering.”

4 The Hebrew expression ![]() (ʾîš ʾîš lammaṭṭeh, lit., “man, man for the tribe”) is distributive: “one man from each tribe”; see Williams, Hebrew Syntax, sec. 15; cf. Nu 9:10; 14:34).

(ʾîš ʾîš lammaṭṭeh, lit., “man, man for the tribe”) is distributive: “one man from each tribe”; see Williams, Hebrew Syntax, sec. 15; cf. Nu 9:10; 14:34).

(b) The names of the men (1:5–16)

5These are the names of the men who are to assist you:

from Reuben, Elizur son of Shedeur;

6from Simeon, Shelumiel son of Zurishaddai;

7from Judah, Nahshon son of Amminadab;

8from Issachar, Nethanel son of Zuar;

9from Zebulun, Eliab son of Helon;

10from the sons of Joseph:

from Ephraim, Elishama son of Ammihud;

from Manasseh, Gamaliel son of Pedahzur;

11from Benjamin, Abidan son of Gideoni;

12from Dan, Ahiezer son of Ammishaddai;

13from Asher, Pagiel son of Ocran;

14from Gad, Eliasaph son of Deuel;

15from Naphtali, Ahira son of Enan.”

16These were the men appointed from the community, the leaders of their ancestral tribes. They were the heads of the clans of Israel.

COMMENTARY

5–15 The names of these luminaries occur again in chs. 2, 7, and 10; as noted above, more is the sadness as the list of those who would die in the wilderness is given three times! Most of these names are theophoric; that is, they are built by compounding one of the designations for God into a name that is a significant banner of faith in the person and work of God. The antiquity of this list of names is revealed by the fact that many are built on the names El (ʾēl, “God”), Shaddai (šadday, traditionally translated “Almighty”), Ammi (ʿammî, “My Kinsman”), Zur (ṣûr, “Rock”) and Ab (ʾab, “Father”). (See also the list naming the leaders of Levitical families in 3:24, 30, 35, where the same patterns are in play.) At a later time in Israel’s history, we would expect many names to be based on the covenantal name Yahweh because of the revelation of this name and its significance (see Ex 2:23–3:15; 34:1–8).

The paucity of names based on Yahweh (e.g., names beginning with “Jeho-” or ending in “-jah” or “-iah”) in this list may be a significant argument for the antiquity of this text (see Notes). Whereas the name Yahweh was available for name-building in the period before the exodus, it did not come into greater use until after the revelation of a new significance of that name in Yahweh’s revelational encounter with Moses and the subsequent teaching of these truths to the populace of Israel. Here are the names and suggested probable meanings (in order of their listing):

- Elizur (ʾelîṣûr, “[My] God Is a Rock”) son of Shedeur (šedê ʾûr, “Shaddai Is a Flame”), chief of Reuben (v.5);

- Shelumiel (šelumî ʾēl, “[My] Peace Is God”) son of Zurishaddai (ṣûrîšaddāy, “[My] Rock Is Shaddai”), chief of Simeon (v.6);

- Nahshon (naḥšôn, “Serpentine”) son of Amminadab (ʿammînādāb, “[My] Kinsman [God] Is Noble”), chief of Judah (v.7);

- Nethanel (netanʾēl, “God Has Given”) son of Zuar (ṣû ʿār, “Little One”), chief of Issachar (v.8);

- Eliab (ʾelî ʾāb, “[My] God Is Father”) son of Helon (ḥēlōn, “Rampart-like” [?]), chief of Zebulun (v.9);

- Elishama (ʾelîšāmāʿ, “[My] God Has Heard”) son of Ammihud (ʿammîhûd, “[My] Kinsman [God] Is Majesty”), chief of Ephraim (v.10);

- Gamaliel (gamlî ʾēl, “Reward of God”) son of Pedahzur (pedâṣûr, “The Rock [God] Has Ransomed”), chief of Manasseh (v.10);

- Abidan (ʾabîdān, “[My] Father [God] Is Judge”) son of Gideoni (gid ʿōnî, “My Hewer”), chief of Benjamin (v.11);

- Ahiezer (ʾaḥî ʿezer, “[My] Brother [God] Is Help”) son of Ammishaddai (ʿammîšadāy, “[My] Kinsman [God] Is Shaddai”), chief of Dan (v.12);

- Pagiel (pagʿî ʾēl, “Encountered by God”) son of Ocran (ʿokrān, “Troubled”) chief of Asher (v.13);

- Eliasaph (ʾelyāsāp, “God has Added”) son of Deuel (deʿû ʾēl, “Know God!”), chief of Gad (v.14; see Note at 2:14);

- Ahira (ʾaḥîraʿ, “My Brother Is Evil”) son of Enan (ʿênān, “Seeing”), chief of Naphtali (v.15).

Noth, 13–19, argues that the source for this material is the putative P (late in the fifth century BC) because of the schematic nature and orderliness of presentation, but that the name lists that P used in his record must have come from a very early period in Israel’s experience (at least from a pre-Davidic period). His admission of the antiquity of the names is in fact something that may slightly undermine his approach to the writing of this text.

16 The Hebrew adjective underlying the phrase “the men appointed” (qārîʾ, singular) is a technical term for representatives used only here and in 26:9. Verse 16 is legal, formal, and precise in tone. Three phrases are used to give sanction to each of these leaders. Levi is not represented in this list (see 1:47).

NOTES

5 On the problems and precarious nature of attempting to discover the precise meaning of Hebrew names, see comments on 13:4–15. The meaning we may adduce for a biblical name is a bit tenuous, as the meaning cannot be determined by context in the same manner as with other nouns and verbs. Most of the suggested translations given here are from BDB. The argument for the antiquity of the list, based on the phenomenon of the patterns of formation, is significant because it is “substructural.” That is, if these lists were fraudulent concoctions from a later period (as critical scholars allege), the tendency would have been for the forger to use nominal patterns of the period of the writing—unless, of course, the creative forger knew that by using antique patterns of names he (she?) would fool later (modern?) readers!

16 The Hebrew word ![]() (nāśîʾ, “leader”; GK 5954) speaks of one who is “lifted up” or “selected.” The noun is derived from the verb

(nāśîʾ, “leader”; GK 5954) speaks of one who is “lifted up” or “selected.” The noun is derived from the verb ![]() (nāśāʾ, “to lift up”; GK 5951). The vowel pattern of this noun is the same as that for the word “prophet,”

(nāśāʾ, “to lift up”; GK 5951). The vowel pattern of this noun is the same as that for the word “prophet,” ![]() (nābîʾ). It presents a passive infix.

(nābîʾ). It presents a passive infix.

(c) The summary of the census (1:17–19)

17Moses and Aaron took these men whose names had been given, 18and they called the whole community together on the first day of the second month. The people indicated their ancestry by their clans and families, and the men twenty years old or more were listed by name, one by one, 19as the LORD commanded Moses. And so he counted them in the Desert of Sinai:

COMMENTARY

17 This verse indicates the leadership of Moses and Aaron in the task, as it does their obedience to the command of Yahweh. This chapter is marked by a studied triumphalism. Numbering the tribes and mustering the army were sacred functions that prepared the people for their war of conquest under the right hand of God, who was their Warrior (see Ex 15:3, “The LORD is a warrior”).

18 The expression “twenty years or more” is taken by Gershon Brin (“The Formulae ‘From . . . and Onward/Upward,’” JBL 99 [1980]: 161–71) to indicate generational identity; i.e., one who was under the age of twenty was still regarded as a member of his father’s house, while one over the age of twenty was an individual who was morally and civilly responsible.

19 Hebrew prose often gives a summary statement and follows with details that explicate the summary. This verse is that summary, and verses 20–43 present the details. Genesis 1:1 may be viewed as a similar summary statement, the details being given in the rest of the chapter.

(d) The listings of the census by each tribe (1:20–43)

20From the descendants of Reuben the firstborn son of Israel:

All the men twenty years old or more who were able to serve in the army were listed by name, one by one, according to the records of their clans and families. 21The number from the tribe of Reuben was 46,500.

22From the descendants of Simeon:

All the men twenty years old or more who were able to serve in the army were counted and listed by name, one by one, according to the records of their clans and families. 23The number from the tribe of Simeon was 59,300.

24From the descendants of Gad:

All the men twenty years old or more who were able to serve in the army were listed by name, according to the records of their clans and families. 25The number from the tribe of Gad was 45,650.

26From the descendants of Judah:

All the men twenty years old or more who were able to serve in the army were listed by name, according to the records of their clans and families. 27The number from the tribe of Judah was 74,600.

28From the descendants of Issachar:

All the men twenty years old or more who were able to serve in the army were listed by name, according to the records of their clans and families. 29The number from the tribe of Issachar was 54,400.

30From the descendants of Zebulun:

All the men twenty years old or more who were able to serve in the army were listed by name, according to the records of their clans and families. 31The number from the tribe of Zebulun was 57,400.

32From the sons of Joseph:

From the descendants of Ephraim:

All the men twenty years old or more who were able to serve in the army were listed by name, according to the records of their clans and families. 33The number from the tribe of Ephraim was 40,500.

34From the descendants of Manasseh:

All the men twenty years old or more who were able to serve in the army were listed by name, according to the records of their clans and families. 35The number from the tribe of Manasseh was 32,200.

36From the descendants of Benjamin:

All the men twenty years old or more who were able to serve in the army were listed by name, according to the records of their clans and families. 37The number from the tribe of Benjamin was 35,400.

38From the descendants of Dan:

All the men twenty years old or more who were able to serve in the army were listed by name, according to the records of their clans and families. 39The number from the tribe of Dan was 62,700.

40From the descendants of Asher:

All the men twenty years old or more who were able to serve in the army were listed by name, according to the records of their clans and families. 41The number from the tribe of Asher was 41,500.

42From the descendants of Naphtali:

All the men twenty years old or more who were able to serve in the army were listed by name, according to the records of their clans and families. 43The number from the tribe of Naphtali was 53,400.

COMMENTARY

20–43 For each tribe there are two verses in repetitive, formulaic structure giving: (1) the name of the tribe, (2) the specifics of those numbered, (3) the name of the tribe restated, and (4) the total enumerated for that tribe.

Certainly one of the most difficult issues in the book of Numbers concerns the large numbers of these lists. Noth, 21, places the issue darkly: “The main problem of the section 1.20–46 consists in the figures that are given. Their size, as is generally recognized, lies outside the sphere of what is historically acceptable. In no sense do they bear even a tolerable relationship to what we otherwise know of the strength of military conscription in the ancient East.”

More recently Budd, 6, concurs, “The central difficulty here is the impossibly large numbers of fighting men recorded. The historical difficulties in accepting the figure as it stands are insuperable.” More conservative writers concur. Here is an assessment by LaSor, Hubbard, and Bush (OTS–1996, 105):

Most cities that have been excavated [in Israel] cover sites of a few acres that could have housed a few thousand people at the most. At no time would Palestine [Israel] have had more than a few dozen towns of any significant size. Every bit of available evidence, biblical, extrabiblical, and archaeological, seems to discourage interpreting the numbers literally.

That the numbers for each of the tribes are rounded may be seen in that each unit is rounded to the hundreds (but Gad to the fifties [1:25]). A peculiarity in the numbers that leads some to believe they may be symbolic is that the hundreds are grouped between two hundred and seven hundred; there are no hundreds in zeros, one hundreds, eight hundreds, or nine hundreds. Yet whatever we may make of these factors, we may observe that the same numbers are given for each tribe in ch. 2, where there are four triads of tribes with consistent use of numbers, sums, and grand totals. Further, the total might have been rounded to six hundred thousand but was not (see 1:46; 2:32).

In this chapter the Hebrew word translated “thousand” (ʾelep) is clearly taken to mean one thousand for the total to be achieved in verse 46. Varied suggestions have been made (such as that by Noth) that demand the totals arose only in a later period in which there was confusion about the unusual meaning of the term ʾelep in this section. But that appears to be an attempt to play the game from two sides. The passage cannot have come from a later time (as is believed by documentarians; this is a “P text”!), and yet contain a misuse of the word ʾelep—at the time of the writing. (See the extensive treatment of this term in the Introduction: The Problem of the Large Numbers).

Because the descendants of Levi were excluded from the census (see on v.47), the descendants of Joseph are listed according to the families of his two sons, Ephraim (vv.32–33) and Manasseh (vv.34–35). In this way, the traditional tribal number of twelve is maintained, and Joseph is given the “double portion” of the ranking heir of Jacob (cf. Ge 49:22–26; Dt 33:13–17). Second Kings 2:9 is also to be understood in this manner; Elisha was not asking Elijah that he might have double the power of his master or that he might do double the number of miracles of his mentor. Rather, of all the sons of the prophets who might wish to be regarded as the proper heir of Elijah, Elisha desired that honor for himself. The phrase “a double portion of your spirit” suggests the honor of the privileged son who would receive a double share of the inheritance of the father.

(e) The summary of the census (1:44–46)

44These were the men counted by Moses and Aaron and the twelve leaders of Israel, each one representing his family. 45All the Israelites twenty years old or more who were able to serve in Israel’s army were counted according to their families. 46The total number was 603,550.

COMMENTARY

44–46 As noted in the introduction, there appears to be no textual difficulty in the Hebrew tradition in the soundness of this large number (or the integers used to achieve it) for the census of the fighting men of Israel. The number 603,550 is the proper sum of the twelve components listed in verses 21–43. And there is no convincing unusual meaning suggested for the word “one thousand” (ʾelep).

The mathematics of these numbers is accurate and complex. It is complex in that the totals are reached in two ways: (1) a linear listing of twelve units (1:20–43), with the total given (1:46); (2) four sets of triads, each with a subtotal, and then the grand total (2:3–32), which equals the total in 1:46. These numbers are also consistent with the figures in Exodus 12:37–38 (“about six hundred thousand men on foot, besides women and children”) and in Exodus 38:26 (603,550 men of twenty years old or more). Furthermore, they relate well to the figures of the second census in Numbers 26:51 (601,730 men) at the beginning of the new generation. This large number of men conscripted for the army suggests a population for the entire community in excess (perhaps considerably) of two million people.

There are at least three implications we may draw from this immense number: (1) Moses was responsible for this immense number of people in the most difficult of circumstances, the management task God gave to Moses being exceedingly demanding; (2) the demands on God’s providence (and overt miracle) were immense during the generation of wilderness sojourn; and (3) in the end, all those people who were numbered, along with the women and the other males not counted—all of them, excepting only Joshua and Caleb, would die in the wilderness because of their collective act of unbelief in the power of God and their lack of trust in his faithfulness to his promise.

Another concept related to these large numbers concerns the wonders in the fulfillment of the particular blessing of God in the unusual growth of the people of the family of Jacob in Egypt. Exodus 1:7 describes in five Hebrew phrases the stunning growth of the Hebrew people in Egypt during the four centuries of their sojourn. So numerous had the Hebrew people become that they were regarded as a threat to the security of Egypt (Ex 1:9–10, 20). Israel’s numerical growth from the seventy who entered Egypt (Ex 1:5) was an evidence of God’s great blessing and his faithfulness to his covenant with Abraham (Ge 12:2; 15:5; 17:4–6; 22:17). The growth of the nation was God’s benediction on them. As we are troubled with the immensity of the numbers, we should not neglect to reflect on this benediction the numbers present and respond to the Lord in gratitude.

It is not necessary to magnify difficulty in order to praise God. As we return to the difficulty of these numbers, we find ourselves concluding with most critical scholars and many conservative scholars that these numbers cannot be what they first appear to be. Yet because of the manner in which they are added together, we may find ourselves uncomfortable with those suggestions that speak of earlier understandings that the later scribes forgot. To speak of their adding hundreds and “thousands” as an “understandable error” is a troubling expression. Understandable error is still error.

So we return to the position suggested in the Introduction: The Problem of the Large Numbers. We may treat these numbers as “real” numbers (better, “common numbers”), even as the text appears to present them. The hundreds were added to the thousands as in all such sums. But these numbers (in terms of their addition) are numbers that were used for effect. I suggest there is a deliberate exaggeration, a rhetorical device used to give praise to God and hope to his people, of the sums for each tribe and hence for the total. By deliberately magnifying these numbers by a common factor (ten, the number of the digits), the writer was able to use them as “power words.” That is, the ancients who were the recipients of these words knew what we may have forgotten, that numbers may be used for purposes other than merely reporting data.

By deliberately exaggerating the numbers of the fighting men of the tribes of Israel, the point achieved was a type of “believers’ braggadocio!” The nation that had been crafted by God within the context of slavery and servitude was now a power to be reckoned with among the great powers of the ancient world. More, God had promised that the descendants of Abraham would outnumber the stars, would be more numerous than grains of sand on the shore of the sea. The unprecedented growth of the nation fulfilled numerous promises of God to the fathers (see Ge 17:2, 6; 22:17; 26:4; 28:14; 35:11; 48:4). Moses was able to use the patriarchal phrase of abundance as he recounted his experience as their leader: “The LORD your God has increased your numbers so that today you are as many as the stars in the sky” (Dt 1:10; cf. Ex 32:13).

Moreover, the greatly inflated numbers promise greater things to come. One day, families of all nations will find their blessing in the same God who brought blessing to Abraham. One day the Seed of Abraham will be the Savior of the world. Big numbers at the beginning are a promise of even bigger numbers at the end! If numbers have ever been used for propaganda (!), here, it appears, is a biblical precedent for the exaggeration of numbers in praise of God.

We may ask: What is the role of deception in all this? The answer is simple, even if it may not be convincing to some. None of those who first read these words would have been deceived. All would have known that these “power numbers” far outstripped the acutal facts of the day. The appearance of deception arises only when the conventions of using numbers in these manners are forgotten.

Here is an example of the “proper role” of archaeology as it relates to the Bible. When surveys of excavated sites in the little land of Israel present city mounds (tells) that are measured in acres instead of in tens of miles squared, when actual house plans are surveyed within these city mounds and extrapolations are made of the numerical possibilities these ancient plots present—well, then, these and other considerations gel together to help one come to a reappraisal of the actual facts of the case. In the process we are in a discovery of the “original meaning” of the biblical text. For the “original meaning” does not just come in a parsing of verbs or a word study of nouns or a syntactical study of a clause—original meaning also includes the manner in which the ancient writers used these verbs, nouns, and clauses—and numbers.

Here is the clincher: how they used numbers was their concern! It is not up to modern readers to sit in judgment; our task is merely to understand, to appreciate, and then to begin to share with the ancients their joy in these exquisite numbers! Hence, in the alchemy of the mind in one’s new appreciation of numbers, we join them in their celebration.

(f) The reason for the exclusion of the Levites (1:47–54)

47The families of the tribe of Levi, however, were not counted along with the others. 48The LORD had said to Moses: 49“You must not count the tribe of Levi or include them in the census of the other Israelites. 50Instead, appoint the Levites to be in charge of the tabernacle of the Testimony—over all its furnishings and everything belonging to it. They are to carry the tabernacle and all its furnishings; they are to take care of it and encamp around it. 51Whenever the tabernacle is to move, the Levites are to take it down, and whenever the tabernacle is to be set up, the Levites shall do it. Anyone else who goes near it shall be put to death. 52The Israelites are to set up their tents by divisions, each man in his own camp under his own standard. 53The Levites, however, are to set up their tents around the tabernacle of the Testimony so that wrath will not fall on the Israelite community. The Levites are to be responsible for the care of the tabernacle of the Testimony.”

54The Israelites did all this just as the LORD commanded Moses.

COMMENTARY

47–49 The Levites, because of their sacral tasks, were excluded from this military listing; they were to be engaged in the ceremonies and maintenance of the tabernacle. Chapter 3 discusses their families, numbers, and functions.

50 As in Exodus 38:21, the sanctuary is here called “the tabernacle of the Testimony.” The “Testimony” refers to the Ten Words (Ten Commandments) written on stone tablets (Ex 31:18; 32:15; 34:29). These tablets were placed in the ark (Ex 25:16, 21; 40:20), leading to the phrase “the ark of the Testimony” (Ex 25:22; 26:33–34; et al.). In Psalm 19:7[8] the Hebrew term ʿēdût (“testimony”; “statutes,” NIV) is used for the word of God in a more general sense but still with the background of the Ten Words of Exodus.

51–52 The Hebrew word hazzār, rendered “anyone else” (v.51), is often translated “stranger, alien, foreigner” (as in Isa 1:7; Hos 7:9). Thus a non-Levitical Israelite was considered an alien to the religious duties of the tabernacle (see Ex 29:33; 30:33; Lev 22:12). The punishment of death is reiterated in Numbers 3:10, 38; 18:7 and was enacted by divine fiat in 16:31–33 (see 1Sa 6:19). The sense of the Divine Presence was both blessing and cursing in the camp: blessing for those who had a proper sense of awe and wonder of the nearness of deity, and cursing for those who had no sense of place, no respect for the Divine Presence.

53 The tents of the Levites are detailed in 3:21–38. The encampment of the Levites around the tabernacle was a protective hedge against trespassing by the laity (non-Levites) to keep them from incurring the wrath of God. The dwelling of the Levites around the central shrine was a measure of God’s grace and a reminder of his presence.

54 In view of Israel’s great disobedience in the later chapters of Numbers, these words of initial compliance to God’s word have a special poignancy. Israel began so well, then failed so terribly; her experience remains a potent lesson to all people of faith who follow them. Ending well is the desire. Most racers get off the blocks reasonably well, but the winner is only certified as such at the end of the course.

ii. The placement of the tribes (2:1–34)

OVERVIEW

Chapter 2 has a symmetrically arranged structure (see Introduction: Outline). The details of this chapter are presented in studied orderliness as a literary exhibit of the physical symmetry expected of the peoples who would be encamped around the central shrine. As in the case of ch. 1, the details of this chapter seem to reflect the joy of the writer in knowing the relation each tribe has to the whole, each individual to the tribe, and the nation to the central shrine—and how all relate to the Lord Yahweh. Thus in some manner this chapter is another means of bringing glory to God. The book of Numbers should be read as a book of the worship of Yahweh! There is an element of pride, joy, and expectation in the seemingly routine matters of this chapter. Here was the place of encampment for each tribe in proximity to the Divine Presence, and from these camps the people would set out under the hand of God to enter the Land of Promise and take possession in his power. The chapter should be read with expectation that the conquest will be as orderly and purposeful as the place of camping in the wilderness.

There is a sense in which the orderliness of these early chapters of Numbers is akin to the orderliness of Genesis 1. As God has created the heavens and the earth and all that fills them with order, beauty, purpose, and wonder, so he constituted his people with order, beauty, purpose, and wonder. And as the heavens and earth may “praise” God in their responses to his commands (Ps 147:13–18), so the peoples of God may praise him in their responses to his commands (Ps 147:19–20). Indeed, his people must praise him.

Critical scholars respond to the orderliness and symmetry of this text in quite another manner. N. H. Snaith (Leviticus and Numbers [NCB; Greenwood, SC: Attic, 1967], 186), for example, regards the whole chapter “as an idealistic reconstruction to fit in with later religious ideas.” For such writers, the very beauty of the text becomes its downfall. For ourselves, let the beauty of the text be its strength and lead us to be reflective of the beauty of the Lord in the midst of his people.

1The LORD said to Moses and Aaron: 2“The Israelites are to camp around the Tent of Meeting some distance from it, each man under his standard with the banners of his family.”

COMMENTARY

1 The standard pattern of formal Hebrew prose is followed in this chapter. First there is an announcement of the topic, and then come the details of that topic in an orderly presentation, followed finally by a summary of the whole. This type of organization must have been satisfying to the ancient writers by its giving a sense of wholeness, direction, and orderliness to an account. As in the case of ch. 1, material of this sort may fail to excite the modern reader. Yet if one pauses to think of the order and structure of the text, the underlying significance of the passage may be realized more easily. God is about to bring to pass a great marvel with his people, but it only will occur as they are rightly related to him and to one another.

The relatedness of the people round about the central shrine was the essence of their meaning as a people. Apart from this order, the Hebrews would have remained a disorganized group, nearly a mob—large, disorganized, unruly, and bound for disaster. With this pattern and the discipline and devotion it implied, there was the opportunity for grand victory. The order of the chapter is a promise of the fulfillment of the working of God in their midst. That Israel in fact did fail God is the sadder story, for he had given to them the means for full success.

This chapter begins with the announcement of the revelation of the Lord to Moses and Aaron (using the Hebrew verb dābar in the Hiphil, “to speak”). The more usual phrasing in the Torah is “And Yahweh spoke to Moses, saying,” as in 1:1. Here the words “and Aaron” are added, as in 4:1, 17; 14:26; 16:20; 19:1. A similar phrase (with a different Heb. verb, ʿāmar, “to say”: “And the LORD said to Moses and Aaron”) is found in 20:12, 23. The reference to Aaron along with his illustrious brother in this chapter indicates the strong focus on the shrine of God’s presence in the center of the camp. Aaron, as will be detailed in ch. 3, had the principal task of maintaining the purity, order, and organization of the work respecting the central shrine.

2 The Hebrew word order of verse 2 stresses the role of the individual in the context of the community; each one was to know his or her exact position within the camp. A more literal translation, following the studied order of the Hebrew original, follows:

Each by his standard,

by the banners of their fathers’ house,

the Israelites will encamp;

in a circuit some way off from the Tent of Meeting

they will encamp.

The repetition of the verb “will encamp” is for stately stress. Here was the meaning of the individual in Israel, and here was the significance of his family.

The people of Israel were a community that had their essential meaning in relationship to God and to one another. But ever in the community was the continuing stress on the individual to know where one belonged in the larger group. Corporate solidarity in ancient Israel was a reality of daily life, but the individual was also very important. The words interplay in these texts: each individual/the people // the people/each individual.

The text stresses not just the relationship each person and each tribe was to have to the central shrine but also that no one was to approach the shrine too casually. The dwelling of the tribes was in a circuit about the shrine but at some distance from it. The Hebrew word minneged means “some way off” or “from a distance.” These words build on 1:52–53 and the protective grace of God, demanding a sufficient distance to serve as a protective barrier from any untoward approach to the shrine of the Divine Presence. The warning was to prevent the judgment of God that such an approach might provoke. Gerhard von Rad, 2:374–78, writes that all true knowledge of God begins with the assertion of his hiddenness. Too casual an approach betrayed too minimal a reverence.

Here we sense anew a recurring theme in the Torah: God’s holiness may not be forgotten by his people, but his grace is protective for them. His desire was not to destroy the unwary but to protect such from their own folly—and to demonstrate the wonder of his person in the midst of their camp.

God could have maintained “distance” between himself and the people, thus rendering the warning unnecessary. Then no one would be in danger of harm. The true believer, however, so caught up with the wonder of knowing that the God of the whole universe was present in some mysterious way in the midst of the encampment of the people of the new Israel, would seek to learn to live with the mystery of God’s awesome presence. The fright of danger could be lost in the sense of the proximity of his glory and the nearness of his grace.

Each tribe had its banner and each triad (group of three) of tribes had its standard. Jewish tradition suggests that the tribal banners corresponded in color to the twelve stones in the breastpiece of the high priest (Ex 28:15–21). Further, this tradition holds that the standard of the triad led by Judah had the figure of a lion, that of Reuben the figure of a man, that of Ephraim the figure of an ox, and that of Dan the figure of an eagle (see the four living creatures described in Eze 1:10; cf. Rev 4:7). These traditions are late, however, and difficult to substantiate; Torah does not describe the nature or designs of the banners of Numbers 2 (see KD 3:17).

(b) Details of execution (2:3–33)

(i) Eastern encampment (2:3–9)

OVERVIEW

In ch. 1 the nation was mustered and the genealogical relationships clarified. In ch. 2 the nation was set in structural order; further, the line of march and the place of encampment were established. The numbers of ch. 1 are given in new patterns of arrangement—four sets of triads—but they are the same numbers. The repetition of these grand sums of each tribe is a further reflection of the grace of God in their increase during their sojourn in Egypt. The numbers in chs. 1 and 2 are in agreement; if one offers ways to change the seemingly clear sense of the numbers in ch. 1, then that person also has to deal with the repetitions in this chapter. The same leaders of ch. 1 figure again here and also in 10:14–28. The listing of their names is a matter of significant honor; it is also a matter of sadness. These names were not forgotten in Israel, but their lives were lost in the wilderness, far from the land of God’s gracious promise.

3On the east, toward the sunrise, the divisions of the camp of Judah are to encamp under their standard. The leader of the people of Judah is Nahshon son of Amminadab. 4His division numbers 74,600.

5The tribe of Issachar will camp next to them. The leader of the people of Issachar is Nethanel son of Zuar. 6His division numbers 54,400.

7The tribe of Zebulun will be next. The leader of the people of Zebulun is Eliab son of Helon. 8His division numbers 57,400.

9All the men assigned to the camp of Judah, according to their divisions, number 186,400. They will set out first.

COMMENTARY

3–9 Judah, Issachar, and Zebulun were the fourth, fifth, and sixth of the six sons born to Jacob by Leah. It is somewhat surprising to have these three tribes first in the order of march since Reuben is regularly remembered as Jacob’s firstborn son (1:20). However, because of the perfidy of the three older brothers (Reuben, Simeon, and Levi; see Ge 49:3–7), Judah was ascendant and was granted pride of place among his brothers (49:8). Judah became scion of the royal line in which the Messiah would be born (49:10; Ru 4:18–21; Mt 1:1–16).

Further, the placement on the east was significant in Israel’s thought. East is the place of the rising of the sun, the source of hope and sustenance. Westward was the sea. Israel’s traditional stance was with its back to the ocean and the descent of the sun. The ancient Hebrew people were not a seafaring folk like the Phoenicians and the Egyptians. For Israel the place of pride was on the east; hence there we find the triad of tribes headed by Judah, Jacob’s fourth son, the father of the royal house that leads to King Messiah.

(ii) Southern encampment (2:10–16)

10On the south will be the divisions of the camp of Reuben under their standard. The leader of the people of Reuben is Elizur son of Shedeur. 11His division numbers 46,500.

12The tribe of Simeon will camp next to them. The leader of the people of Simeon is Shelumiel son of Zurishaddai. 13His division numbers 59,300.

14The tribe of Gad will be next. The leader of the people of Gad is Eliasaph son of Deuel. 15His division numbers 45,650.

16All the men assigned to the camp of Reuben, according to their divisions, number 151,450. They will set out second.

COMMENTARY

10–16 Reuben, Jacob’s firstborn son, led the second triad, on the south. As one’s stance in facing eastward has the south on the right hand, there was a secondary honor given to the tribes associated with Reuben. He was joined by Simeon, the second son of Jacob by Leah. Levi, Leah’s third son, was not included with the divisions of the congregation but was reserved the special function of the service of the tabernacle and the guarding of the precinct from the untoward actions of the rest of the community (see v.17 and ch. 3). This triad is completed by Gad, the first son of Leah’s maidservant, Zilpah.

NOTE

14 There is a well-known textual difficulty in 1:14 and 2:14 respecting the name ![]() (deʿû ʾēl, “Deuel”). The MT actually reads

(deʿû ʾēl, “Deuel”). The MT actually reads ![]() (reʿû ʾēl, “Reuel”) here in 2:14 but has “Deuel” in 1:14 and in 7:42. The Hebrew letters dalet

(reʿû ʾēl, “Reuel”) here in 2:14 but has “Deuel” in 1:14 and in 7:42. The Hebrew letters dalet ![]() (d) and resh

(d) and resh ![]() (r) were confused at times by scribes because of their similarity in form. See the NIV’s margin on Genesis 10:4, where a similar problem is presented by the name Rodanim versus Dodanim. Other MSS of the MT, along with the versions, read “Deuel” here in 2:14, which reading I suspect is the superior one.

(r) were confused at times by scribes because of their similarity in form. See the NIV’s margin on Genesis 10:4, where a similar problem is presented by the name Rodanim versus Dodanim. Other MSS of the MT, along with the versions, read “Deuel” here in 2:14, which reading I suspect is the superior one.

(iii) Tent and the Levites (2:17)

17Then the Tent of Meeting and the camp of the Levites will set out in the middle of the camps. They will set out in the same order as they encamp, each in his own place under his standard.

COMMENTARY

17 The tent here is the tabernacle—the great Tent of Meeting in the center of the encampment. This was representative of Yahweh’s presence within the heart of the camp. It is a change from Exodus 33:7–11. Then Moses’ personal tent (see Note) was without the camp, and Moses would go outside the camp to seek the word of God. Here the tent is within the camp, and all Israel was positioned around it. Earlier, the Lord would “come down” from time to time; here he was continually in their midst.

There is a sense here of the progressive manifestation of the presence of God in the midst of the people. First he was on the mountain of Sinai; then he came to the tent outside the camp; then he indwelt the tent in the midst of the camp. One day he would reveal himself through the incarnation in the midst of his people (Jn 1:1–18); and, on a day still to come, there will be an even greater realization of the presence of the person of God dwelling in the midst of his people in the new Jerusalem (Rev 21:1–4). The story of the Bible is largely the story of the progressive revelation of God among his people (Heilsgeschichte—“the history of salvation,” in the “good sense”) and the progressive preparation of a people to be fit to live in his presence.

This verse relates not only to the manner of encampment but especially to the manner of their march. On the line of march the triads of Judah and Reuben would lead the community; next would come the tabernacle with the attendant protective hedge of Levites (see 1:53); then would come the triads of Ephraim and Dan. In this way there was not only the sense of the indwelling presence of God in the midst of the people, there was also the sense that the people in their families and tribes were protecting before and behind the shrine of his presence.

NOTE

17 Some critical scholars have made much of the position of the tent within or without the camp as a means of distinguishing putative sources (JE, the tent without the camp as a source of revelation; P, the tent within the camp as a place of worship). Yet James Orr (The Problem of the Old Testament Considered with reference to Recent Criticism [New York: Scribner’s Sons, 1906], 165–70) showed long ago that the texts agree that it was God’s intention that the regular placement of the tent was to be within the camp, both for revelation and for worship.

(iv) Western encampment (2:18–24)

18On the west will be the divisions of the camp of Ephraim under their standard. The leader of the people of Ephraim is Elishama son of Ammihud. 19His division numbers 40,500.

20The tribe of Manasseh will be next to them. The leader of the people of Manasseh is Gamaliel son of Pedahzur. 21His division numbers 32,200.

22The tribe of Benjamin will be next. The leader of the people of Benjamin is Abidan son of Gideoni. 23His division numbers 35,400.

24All the men assigned to the camp of Ephraim, according to their divisions, number 108,100. They will set out third.

18–24 The tribes descended from Rachel were on the west. Joseph’s two sons, Manasseh and Ephraim, received a special blessing from their grandfather Jacob; but in the process the younger son, Ephraim, was given precedence over Manasseh (Ge 48:5–20). Here, true to Jacob’s words, Ephraim was ahead of Manasseh. Benjamin came last—the lastborn son of Jacob, Joseph’s younger brother, on whom the aged father doted after the presumed death of Joseph.

(v) Northern encampment (2:25–31)

25On the north will be the divisions of the camp of Dan, under their standard. The leader of the people of Dan is Ahiezer son of Ammishaddai. 26His division numbers 62,700.

27The tribe of Asher will camp next to them. The leader of the people of Asher is Pagiel son of Ocran. 28His division numbers 41,500.

29The tribe of Naphtali will be next. The leader of the people of Naphtali is Ahira son of Enan. 30His division numbers 53,400.

31All the men assigned to the camp of Dan number 157,600. They will set out last, under their standards.

COMMENTARY

25–31 Dan was the first son of Bilhah, the maidservant of Rachel. Asher was the second son of Zilpah, the maidservant of Leah. Naphtali was the second son of Bilhah. These, then, are secondary tribes and are positioned on the northern side of the shrine of the presence, as it were, on the left hand. Here again we need to read these texts with the values of the people who first experienced them. Our orientation tends to be to the north, but Israel’s orientation was to the east. In the final settlement of the land, these three tribes situated to the north of the shrine actually settled in the northern sections of the land of Canaan.

32These are the Israelites, counted according to their families. All those in the camps, by their divisions, number 603,550. 33The Levites, however, were not counted along with the other Israelites, as the LORD commanded Moses.

32–33 These verses conform to and summarize 1:44–53. The total number is the same as in 1:46 (see Introduction), and the distinction of the Levites is maintained (see comments on 1:47–53). The arrangement of the numbers of the tribes in triads (each with subtotals, as well as the grand total for the whole) signifies the concept of stability in these large numbers in the text. Suggestions to reduce the numbers to obtain a “more manageable” portrait should be presented with due care for all the citations, not just a few. Kitchen’s suggestions, for example, may be seen as an effective way to lower the gross numbers drastically; but his approach does not appear to manage subsidiary numbers (see Introduction: The Problem of the Large Numbers).

34So the Israelites did everything the LORD commanded Moses; that is the way they encamped under their standards, and that is the way they set out, each with his clan and family.

COMMENTARY

34 As in 1:54, these words of absolute compliance contrast with Israel’s later folly. This verse also speaks of significant order—a major accomplishment for a people so numerous, so recently enslaved, and more recently a mob in disarray. The text speaks well of the administrative leadership of Moses, God’s reluctant prophet, and of the work done by the twelve worthies who were the leaders of each tribe. Certainly the text points to the mercy of God and his blessing on the people. It may have been the beauty of the order of this plan of encampment that led the unlikely prophet Balaam to say, “How beautiful are your tents, O Jacob, / your dwelling places, O Israel!” (Nu 24:5).

Fittingly, Balaam’s words—the gasp of an outsider—became among the most treasured in the community. Cyrus Gordon wrote of them, “They have remained the most cherished passages in Scripture throughout Synagogue history” (Before the Bible: The Common Background of Greek and Hebrew Civilizations [London: Collins, 1962], 41). In receiving praise from the outsider Balaam, the order and beauty of the camp must continue to stir the heart of the faithful to exhibit even more robust praise. Again the book of Numbers, despite our initial misgivings, is a book of worship.

NOTE

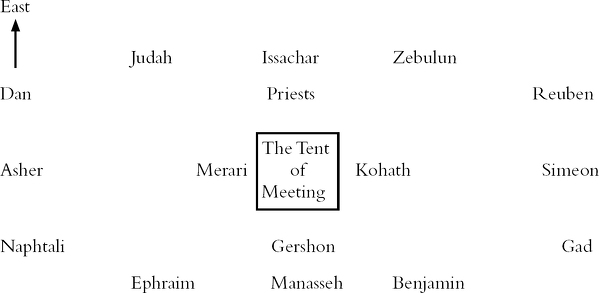

34 The diagram of the camp (with an eastern orientation!) would look like this:

iii. The placement and the numbers of the Levites and firstborn of Israel (3:1–51)

OVERVIEW

The notion of order continues to lace itself unabatedly through this chapter. When the reader slows down to the pace of the text, he or she begins to discover something of the beauty and dignity of these chapters. True, no one would confuse these texts with great literature (but there are texts of sublime artistry in the book; see the Balaam cycle, 22:2–24:25). Dillard and Longman (AIOT, 87) write, “The book of Numbers is not among the literary high points of the Old Testament.” There is nothing in these texts about story, characterization, emotive depth, or literary finesse. These chapters are neither psalm nor proverb, neither oracle nor epic.

This is not to say, however, that these early chapters of Numbers are not written well—for indeed they are. They have about them a stately grace, a dignity, and a sense of presence. When the modern reader attempts to envision the magnitude of the task the Lord gave to Moses to bring order to an immense number of people who were so recently slaves and now so newly free, the resulting sensation the reader may feel is one of overwhelming burden. But these chapters do not speak of burden at all. There is about them a sense of calm control—the control of God himself. In these chapters is an implied call to order in our own lives and affairs—a call that may cut some of us deeply who have grown accustomed to the disaster of disorder.

Not only is each chapter marked by order, but so also is the placement of these several chapters in the book. The first chapter of Numbers records the organization of the nation of Israel along the lines of family, clan, and tribe, with leaders for each tribe and the totals of the fighting men for each of the tribes. Chapter 2 shows how the various tribes are arranged around the central shrine in their encampments. In the midst of the tribes was the shrine, and about the shrine were the priestly and Levitical families who served as a protective hedge for the laity (non-Levites) and as the authorized personnel admitted to handle sacred things on behalf of the people. In ch. 3 we draw closer to the center and observe the families and their numbers who made up these cultic personnel.

(a) The family of Aaron and Moses (3:1–4)

1This is the account of the family of Aaron and Moses at the time the LORD talked with Moses on Mount Sinai.

2The names of the sons of Aaron were Nadab the firstborn and Abihu, Eleazar and Ithamar. 3Those were the names of Aaron’s sons, the anointed priests, who were ordained to serve as priests. 4Nadab and Abihu, however, fell dead before the LORD when they made an offering with unauthorized fire before him in the Desert of Sinai. They had no sons; so only Eleazar and Ithamar served as priests during the lifetime of their father Aaron.

COMMENTARY

1–2 At first blush the wording “the family of Aaron and Moses” (v.1) seems out of order because of the normal placing of Moses before Aaron. But the emphasis is correct: it is the family of Aaron that is about to be described (see v.2). The genealogy of Exodus 6:16–20 (cf. 1Ch 6:1–3) suggests that Aaron and Moses were the (immediate) sons of Amram and Jochebed. However, it is likely that portrayal of this picture is incomplete (a common practice among the writers of these lists in the Bible, and one that must be kept in mind in reading all biblical genealogies, including those of Genesis and Matthew). Amram and his wife-aunt Jochebed were likely more remote ancestors of Aaron and Moses.

At the time of the exodus, there were numerous descendants of Amram, as we learn in this chapter (v.27). Moses’ and Aaron’s sister, Miriam, was the oldest of the three siblings. It was she who kept watch over the infant Moses when he was placed in his boat in the reeds of the Nile (Ex 2:4). Aaron was three years older than Moses (Ex 7:7). Aaron’s wife was Elisheba, the daughter of Amminadab and sister of Nahshon (prince of the tribe of Judah; see Nu 1:7; 2:3), and the mother of the four sons noted in this chapter (see Ex 6:23).

Olson, 98–114, has remarked on the singular importance of the Hebrew term tôledōt(“generations”; “account of the family,” NIV; GK 9352) in verse 1. He regards the phrase “these are the generations of Aaron and Moses” to be the principal link that ties the books of the Pentateuch together. This use of the word tôledōt harks back to the eleven times it is used in the book of Genesis (see Notes). He states (108):

For the first time after the formative events of the exodus deliverance and the revelation on Mount Sinai, the people of Israel are organized into a holy people on the march under the leadership of Aaron and Moses with the priests and Levites at the center of the camp. A whole new chapter has opened in the life of the people of Israel, and this new beginning is marked by the tôledōt formula.

Then Olson, 114, presents the structure of the books of Genesis through Numbers based on the term tôledōt (presented below with slight alteration).

- I. Genesis: The first generations of God’s people to whom the promises were made, and the tôledōt of each succeeding generation up to the tôledōt of Jacob

- II. Exodus: The first generation of God’s people who experienced the exodus out of Egypt and God’s revelation at Mount Sinai; the tôledōt of Jacob

- III. Leviticus: Further instructions to the generations of the exodus and Sinai; the tôledōt of Jacob continued

- IV. Numbers: The death of the old generation and the birth of the new

- A. The continuation of the tôledot of Jacob and the introduction of the tôledōt of Aaron and Moses (Nu 1–25)

- B. The continuation of the tôledōt of Jacob and the tôledōt of Aaron and Moses into a new generation (Nu 26–36)

3 Exodus 28:41 records God’s command to Moses to anoint his brother, Aaron, and his sons as priests of Yahweh (see Ex 30:30; Lev 8:30). This solemn act gave recognition to a special consecration to the Lord and a particular knowledge on their part that they were no longer ordinary—they were now special to God. Olive oil was used commonly to anoint prophets (1Ki 19:16) and kings (1Sa 16:13) for special service to God; but apparently so was the oil of the ancient persimmon (called “balsam” by Greek writers). There is a report of a discovery of a Herodian jug still containing once-fragrant oil of the type used to anoint the kings of Judah. It was found buried in one of the Qumran caves in 1988. In this case the fragrance of the ancient oil came from the (now extinct) ancient persimmon (cf. Joel Brinkley, “Ancient Balm for Anointing Kings Found,” New York Times Service [Feb. 16, 1989]).

Inanimate objects could be anointed as well, for example, the stone at Bethel (Ge 28:18) and the altar of the tabernacle (Ex 29:36). The general Hebrew term meaning “anointed one” (māšîaḥ; GK 5417) became in time the specific term for the Messiah (Christ). While many individuals may be anointed (and be a “messiah”), it is Jesus alone who is the Messiah, the Anointed One, who fulfills all God’s covenantal promises.

This anointing led naturally to being ordained. The Hebrew idiom “who were ordained” literally reads, “to fill the hand” (ʾašer-millēʾ yādām lekahēn, “those whom—he filled their hands—as priest”; see also Ex 29:9; 32:29). The act was an investing of authority, a consecration, and a setting apart. The hands of the anointed ones were filled with an awesome sense of the presence of the divine mystery. These were men of moment, servants of God.

4 For the primary story of Nadab and Abihu, see Leviticus 10:1–2. The accentuation of Numbers 3:2 indicates that Aaron may still have been grieving for his firstborn son, Nadab. The accents lead to the following punctuation: “Now these are the names of the sons of Aaron: the firstborn, Nadab; also Abihu, Eleazar, and Ithamar.” Hirsch, 23, observes, “It is as if the report pauses painfully over Nadab, then lingers on Abihu and then quickly adds Eleazar and Ithamar.” Nadab is given double “honor” in this wording; he is identified as the firstborn, and the accents set his name off from those of his brothers. It is for these reasons that the mysterious report of the sin of Nadab and Abihu is so trenchant to us—and remained so to Aaron!

“Unauthorized fire” translates a Hebrew expression (ʾēš zārâ, “strange fire, alien fire”)—a term that seems deliberately obscure. It is as though the narrator found the concept to be distasteful. This is not unlike the reserve of the Torah in detailing the nuances of the notorious scandal of the behavior of the “sons of God” in Genesis 6:1–4. The essential issue here is that Nadab and Abihu were using fire that the Lord had not commanded (Lev 10:1). The pain of the account is strengthened by its brevity and mystery. We are left at a loss to explain their motivation, just as we do not know the precise form of their error. Were they rebellious or presumptuous? Were they careless or ignorant? Or was their sin some combination of these and other things? The prohibition of wine and beer to the priests in their priestly service, directed in the subsequent text (Lev 10:8–11), may lead us to infer that these sons of Aaron had committed their offense against God while in a drunken state.