The rapid defeat of France in 1940 was one of the most shocking military calamities in modern European history, paralleled by the Prussian catastrophe at Jena in 1806 at the hands of Napoleon. The roots of this defeat are complex and have been the subject of considerable historical controversy ever since.

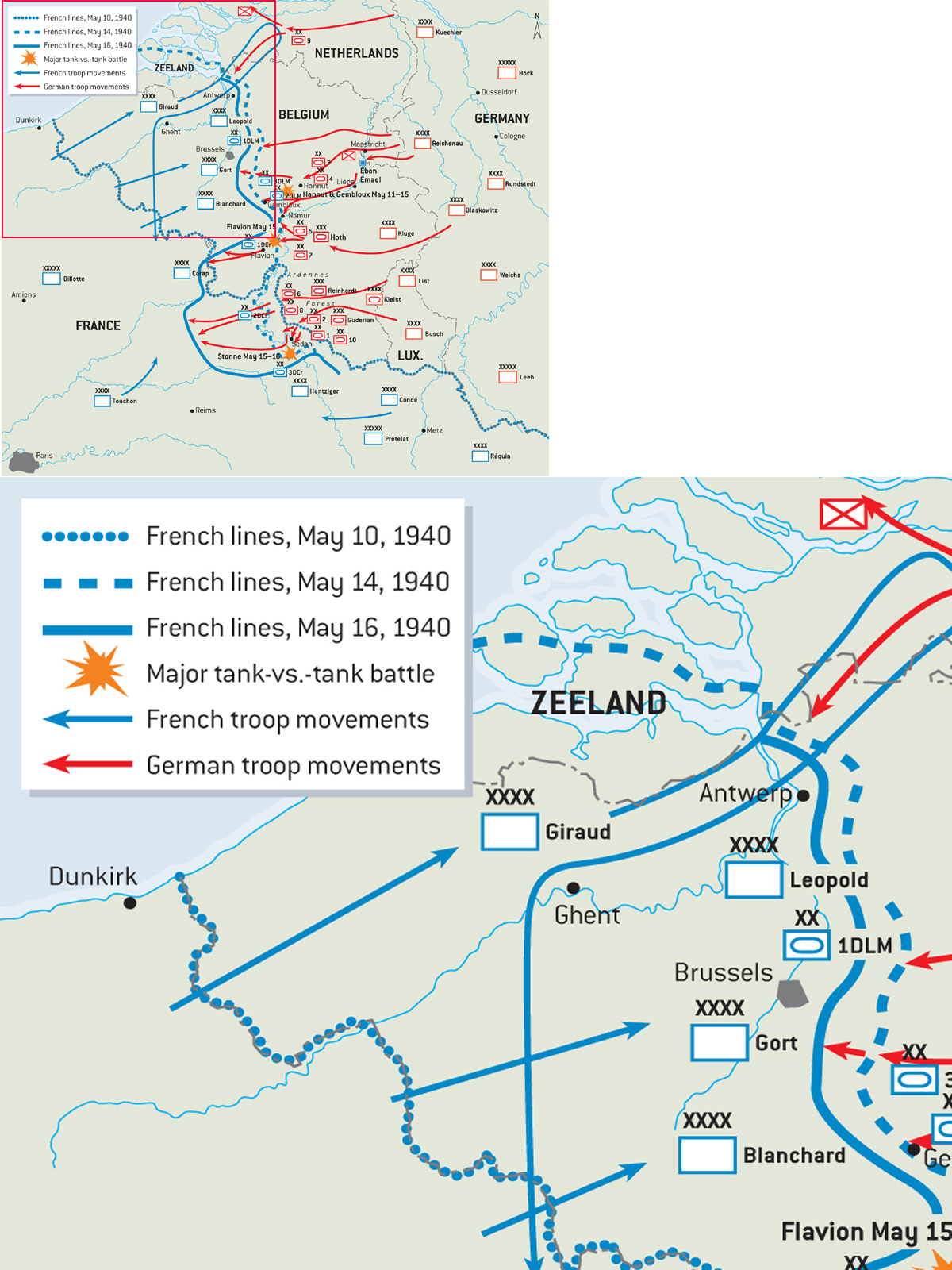

French military policy in the late 1930s was aimed at avoiding defeat rather than at victory over Germany. Bled white by the Great War, and substantially overmatched by German economic power, France created the impressive Maginot Line defenses, along the Moselle in Lorraine and along the Rhine in Alsace, as a centerpiece of its defensive strategy. The fortifications petered out before reaching the Belgian border due to both a lack of funds and a mistaken conviction that the Ardennes presented an insurmountable geographic barrier to German invasion. The Maginot Line was intended to limit Germany’s offensive options, and force the German Army to choose the predictable route through the Netherlands and Belgium. French strategic planning assumed that the Germans would dust off the Schlieffen Plan from 1914, and as a result developed their own response, called Plan D, or the Dyle Plan, after the river where the main defense line would be established. With the Netherlands and Belgium neutral, the French Army and the allied British Expeditionary Force would have to wait for the German attack. When Dutch and Belgian neutrality were violated, the Allies could lunge forward into Belgium, establishing a firm defensive line along the Dyle river. This plan was undermined by a later decision to extend the line towards the Netherlands on the Breda river. It was renamed the Dyle-Breda Plan. This extension forced the French Army to commit its reserve force into Belgium, denying the French commanders a counterattack force should the Germans do something unexpected. Mobility was the key to this plan, and the French forces assigned to Plan D included its only ready mobile force, the cavalry’s DLM in the Prioux cavalry corps.

When Army Group B lunged into the Netherlands and Belgium at the start of the campaign, the French Army responded by surging into Belgium. A major tank battle ensued around the Gembloux gap when Prioux’s cavalry corps threw is mechanized cavalry units into the fray. These Somua S-35 cavalry tanks of the 2e Cuirassiers, 3e DLM, were knocked out during the fighting with the 4.Panzer Division at Merdorp near Hannut, on May 13, during engagements with Pz.Rgt.35, 4.Panzer Division. (NARA)

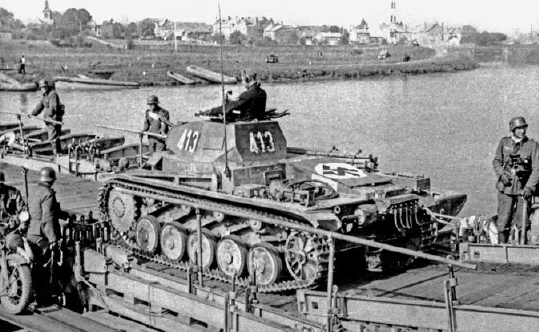

Prior to reaching the Meuse, Guderian’s corps had to cross the Semois river at Bouillon. Here, a PzKpfw I Ausf. B of the 1.Panzer Division begins to ford the Semois on May 12. German engineers had completed a trestle bridge, shown in the background, that day, but it was not sufficient for tank traffic. (NARA)

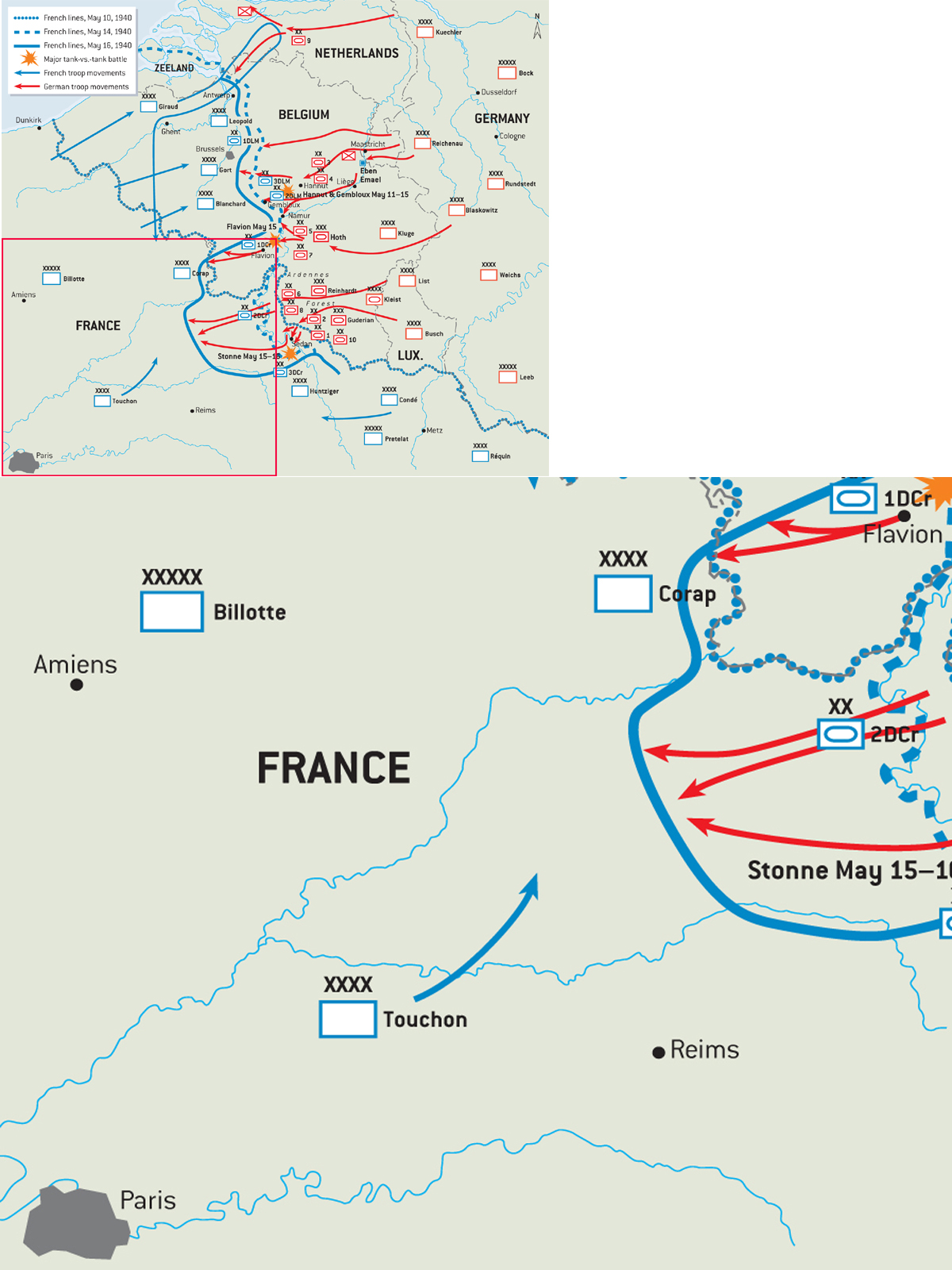

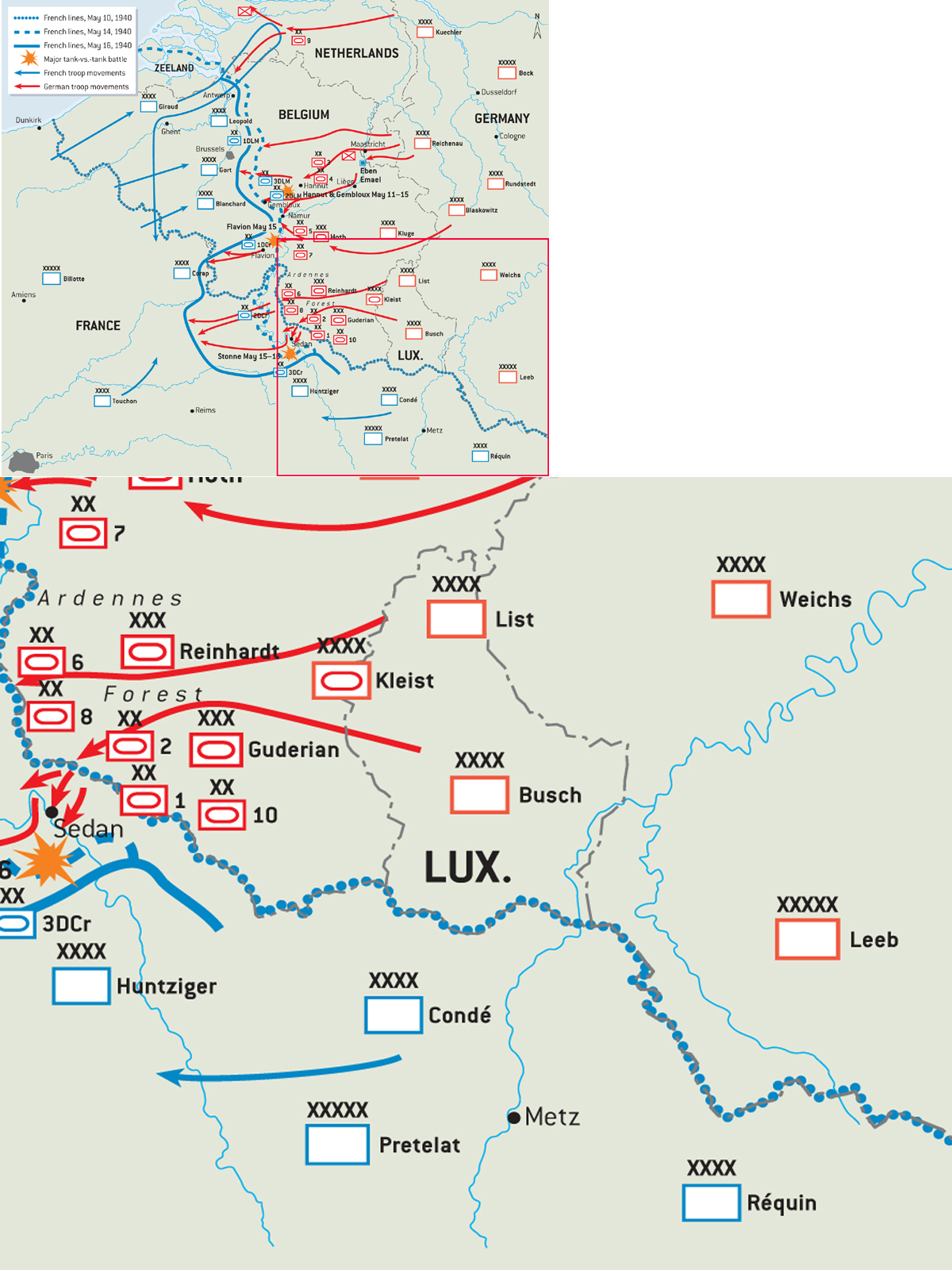

Indeed, the German Army originally did dust off the Schlieffen Plan and intended to crush their way through the Netherlands and Belgium in a mechanized variant of 1914. The most vocal opponent of this plan was the erstwhile Chief of Staff of Army Group A, Erich von Manstein. He argued that such a plan simply allowed the French to push their best units into the narrow Belgian corridor and risked another grotesque stalemate as had occurred in 1914–18. With the new panzer force available, Manstein suggested a far riskier gamble. As in a bull-fight, Army Group B would unfurl the red matador’s cape to entice the Allies’ armored bull forward. By exploiting to French and British preconceptions, the bulk of the best Allied forces would be lured deep into Belgium. The matador’s sword would then come from an unexpected direction. Army Group A with most of the panzer force would quickly slip through the Ardennes in Luxembourg, and exit near Sedan on the Meuse river where the Maginot Line largely ended. Army Group A would then be behind the main Allied force, and a race to the Channel would trap them. Manstein’s plan was an enormous risk since prompt Allied action could blunt the advance out of the Ardennes. However, Manstein’s assessment was that the Allied coalition forces would be sluggish in the opening phase of the campaign, and provide the critical time needed for Army Group A to make an unopposed deep penetration to Sedan and beyond.

The crossing of the Meuse by Guderian’s panzer corps was the critical first phase of the “Sickle Cut” maneuver. Here, a PzKpfw II Ausf. B light tank of 4./Pz.Rgt.1, 1.Panzer Division, crosses the Meuse in the northern suburbs of Sedan over a pontoon bridge on May 14, 1940. The village of Glaire is in the background on the opposite bank. The battle for Stonne, which started the following day, was prompted by this bridgehead. (NARA)

The Char B1 bis of the 1e DCr became entangled with German tanks of Army Group B. “Verdun II” (no. 452) was the command tank of Général de Brigade Bruneau, commander of the 1e Demi-brigade Lourde of the 1e DCR, hence the two stars on the turret. On May 16, the unit became heavily engaged with Rommel’s 7.Panzer Division around Avesnes, and this tank was knocked out late that evening due to a shell hit to its track, near Soire le Château, while commanded by his son, Capt. Bruneau. (Author’s collection)

Panzer Breakthrough at Sedan: May 10–16, 1940

At first, Manstein’s plan fell on deaf ears. As in France, the most senior German commanders viewed the Ardennes as an impenetrable tangle of hills and forest. Three factors shifted the balance in favor of Manstein’s gamble. On a routine flight in bad weather in January 1940, a Luftwaffe officer carrying portions of the Luftwaffe plan for the invasion landed in Belgium. Although the officer managed to destroy most of the maps, there was concern in Berlin that the original plan had been compromised. The conservative nature of the original plan did not appeal to Hitler, and he expressed some vague thoughts about a bolder scheme towards Sedan, the site of the great 1870 German victory. Military aides, sympathetic to Manstein, connived to arrange a meeting between Hitler and Manstein where his Ardennes plan could be explained. Gen. Franz Halder, Chief of the Army’s General Staff, had originally opposed Manstein’s scheme, but after a series of wargames and staff studies in the autumn and early winter of 1939–40, he began to appreciate that such a gamble was Germany’s only way to win a quick and decisive victory against the French and avoid another protracted war akin to 1914–18.

The 4.Panzer Division was part of the “matador’s red cape” with Army Group B attacking through the Netherlands and Belgium. This is one of its PzKpfw IV Ausf. D, evident from the division’s “crow’s foot” insignia on the glacis plate. (NARA)

This confluence of forces led to Manstein’s scheme being adopted as the basis for the final version of Fall Gelb (Case Yellow), the German codename for the attack on France and the Low Countries. The “red cape” role would be played by Army Group B, primarily an infantry force of 29 divisions that would sweep across the Dutch frontier heading for Belgium. The bull-fighter’s sword would be Gerd von Rundstedt’s Army Group A which contained seven of the Army’s ten panzer divisions. These were concentrated in four corps, but the most critical role would be played by von Kleist’s Panzer Group which contained Guderian’s XIX Armee Korps (XIX.AK) and Wietersheim’s XIV.AK which intended to cross the Meuse at Sedan.

The German Army launched its attack on May 10, 1940, adding to the matador’s distraction with dramatic flourishes including an airborne assault on the Belgian fortress at Eban-Emael. The Allies responded as the German plan had anticipated; four Allied field armies marched into Belgium and into the trap. Army Group A’s panzer spearheads began their advance through Luxembourg, attracting little attention. Its pace was imperiled more by traffic jams than by Allied counteraction. On schedule, the German troops appeared at the Meuse on May 13, and after a spectacular Luftwaffe bombardment, German infantry began the river crossings. By the following day, elements of four panzer divisions were over the Meuse and the hapless French reservists in this neglected sector were routed.

Guderian was especially pleased by the performance of his corps. However, one of his greatest anxieties was the presence of the Mont-Dieu plateau south of the Meuse crossing sites which could threaten the bridgehead if occupied by French troops. Guderian expected that sooner or later, the French would stage a counterattack towards Sedan from Mont-Dieu, and indeed such an operation was already underway. To shield the vital Meuse bridgehead while Guderian’s panzers raced westward, 10.Panzer Division was assigned the task of seizing and holding the Mont-Dieu plateau. The fighting for Stonne on Mont-Dieu is the setting for the duel between the PzKpfw IV and Char B1 bis in one of the most violent battles of the 1940 campaign.