4

Peace at Dayton and the “Hubris Bubble”

Within an hour on a snowy November morning near Dayton, Ohio, a sure failure in diplomacy1 swung improbably to breakthrough success. At almost the last moment possible in an extraordinary negotiation that had lasted three weeks and had careened from despair to optimism and back again, a deal came together to end Europe’s deadliest and most vicious war since the time of the Nazis. The agreement at Dayton brought a fragile and uneasy peace to faraway Bosnia and Herzegovina, the theater of nearly four years of grim savagery and, until November 1995, serial diplomatic failure. The deal was brokered by the United States but salvaged, incongruously, at the eleventh hour by a pudgy, cold-eyed despot who had been most responsible for years of turmoil and bloodletting in the Balkans.

The talks were a fascinating collision of ego, power, veiled threats, arcane cartography, arm-twisting, and nights with little sleep. Seldom was the diplomacy of the late twentieth century so fraught or consequential. To revisit the Dayton talks is to reexamine an exceptional moment in American statecraft and to recall an episode that helped make 1995 a watershed year.

The negotiations at Dayton uniquely brought together the leaders of the warring parties in Bosnia—three men who were well-acquainted but could not stand one another. They met at the Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, a sprawling place that projected constant and unsubtle reminders of American military might. The talks were animated by a colorful American official who spoke loudly, assertively, and often to great effect. Dayton was his prized accomplishment.

The negotiations not only brought an end—an all-too-belated end, critics said—to the war in Bosnia; they revived a spirit of “American Exceptionalism” and launched the United States on a trajectory of increasingly forceful interventions abroad. Diplomatic success at Dayton gave rise to an interlude of American muscularity, both diplomatically and militarily—a willingness to take the lead, a willingness to use force in the pursuit of diplomatic objectives, and a willingness to sidestep or ignore the United Nations.

Revitalized “American Exceptionalism”—a malleable sentiment that has coursed deep in American culture and holds that the United States is a singularly virtuous force in a dangerous and troubled world—was accompanied by a growing sense of hubris, a “hubris bubble” that expanded as success begot ambition,2 leading ultimately to anguish in Iraq in the aftermath of the invasion that toppled Saddam Hussein in 2003. Diplomatic success at Dayton brought the rhetoric of “American Exceptionalism” back in a full-throated way. President Bill Clinton gave it voice at the White House that November day, in announcing that agreement had been reached at Dayton. “The central fact for us as Americans is this,” Clinton said. “Our leadership made this peace agreement possible and helped to bring an end to the senseless slaughter of so many innocent people. . . . Now American leadership, together with our allies, is needed to make this peace real and enduring.”3

The war in Bosnia was the longest and most vicious in a series of conflicts touched off by the post–Cold War disintegration of Yugoslavia. Of the six constituent republics of the socialist Yugoslav Federation, Bosnia was the most ethnically diverse. It was a sort of Yugoslavia in miniature.4 None of Bosnia’s ethnicities—Croat, Muslim, and Serb—constituted a majority.

As Yugoslavia’s republics began peeling away in 1991—first Slovenia, then Croatia, then Macedonia—Bosnia’s Muslim government found itself in the unwelcome position of either remaining in a Serb-dominated rump Yugoslavia or leaving and facing the wrath of Bosnian Serbs who wanted no part of secession.5 Following a referendum in late February 1992, Bosnia’s parliament declared the country’s independence, and the Bosnian Serbs responded with armed force, sweeping across 70 percent of Bosnian territory and 30 percent of Croatia in the first weeks of the war. The Serbs laid siege to Sarajevo, Bosnia’s capital and site of the Winter Olympic games of 1984; they drove hundreds of thousands of Muslims and Croats from their homes and forced many more into concentration camps in a brutal campaign of “ethnic cleansing.”6 On the eve of 1995, an interagency U.S. intelligence report found that “sustained campaigns of ethnic cleansing by Bosnian Serbs since 1992 have resulted in the deaths of tens of thousands of non-Serbs, the displacement of hundreds of thousands more, and the radical recasting of Bosnia’s demographic makeup.”7

The Muslim-led Bosnian government had also faced assault by Bosnian Croats, who received arms and ammunition from Croatia and, in 1993, launched their own land grab in southern Bosnia.8 The leaders of Serbia and Croatia dreamed for a time of carving up Bosnia, establishing an ethnically pure “Greater Serbia” and an ethnically pure “Greater Croatia” while leaving the Bosnian government with little more than landlocked enclaves around Sarajevo.9

Few Americans were familiar or conversant with the mind-numbing intricacies of the Balkans, and they mostly turned away from the region’s conflicts and horrors. Nearly 80 percent of Americans responding in a nationwide survey in January 1993 gave the wrong answer, or said they did not know, which ethnic group had conquered most of Bosnia and had encircled Sarajevo. Just one respondent in five in that survey correctly identified the Serbs.10 Polls also showed that Americans mostly were clueless as to how the war in Bosnia began, and few of them saw any vital U.S. interests at stake in the Balkans.11 Surveys also indicated that Americans felt no moral obligation to intervene to end the fighting there.12

It was a fratricidal war utterly without redeeming figures. Of all the perfidious characters who were prominent in 1995, few were as profoundly offensive as Ratko Mladić, Slobodan Milošević, or Franjo Tuđman. Their very names seemed to ooze hostility. Mladić was the burly and swaggering commander of the Bosnian Serb military who once told his gunners on the heights above Sarajevo: “Shell them till they’re on the edge of madness.”13 Twenty years later, Mladić is on trial at The Hague, answering charges of war crimes in Bosnia. Milošević promoted an ultranationalist vision of “Greater Serbia” and was principally responsible for fomenting the turmoil in the Balkans. Milošević—called by his biographers “the Saddam Hussein of Europe”14—died in a prison cell in 2006 while on trial at The Hague for war crimes. But, as we will see, it was Milošević’s intervention that rescued the Dayton talks at their final hour.

Tuđman was the nationalist Croatian president who loved wearing ice cream–colored military uniforms festooned with gold brocade,15 despised the Muslims of Bosnia, and dreamed of uniting ethnic Croats in a “Greater Croatia” under his leadership.16 Tuđman died in 1999 before he could be indicted for war crimes.17 Alija Izetbegović, the beleaguered Muslim president of Bosnia, once likened Milošević and Tuđman to leukemia and a brain tumor.18 And Izetbegović, Milošević, and Tuđman were leaders of the respective Bosnian, Serb, and Croat delegations to Dayton.

A rare occasion when Americans did turn sustained attention to Bosnia came in June 1995, when Scott F. O’Grady, a U.S. Air Force pilot, was shot down over western Bosnia on a routine surveillance mission under NATO auspices.19 It was unclear at first whether O’Grady had survived the destruction of his F-16 fighter jet, blasted from the sky by a Serb surface-to-air missile.20 Intercepted radio transmissions, however, soon indicated that the Serbs had found O’Grady’s parachute and were looking for the downed pilot. O’Grady likened himself to a “scared little bunny rabbit,” saying: “Most of the time, my face was in the dirt, just praying that no one would see me.”21

For nearly six days, O’Grady eluded his Serb would-be captors, sleeping little, drinking rainwater, and eating plants and insects after his rations ran out. A transmission from his radio, in his call sign “Basher 52,” was picked up early on June 8, 1995. A massive rescue mission soon was set in motion from the USS Kearsarge, an amphibious assault ship in the Adriatic Sea. Forty warplanes and support aircraft, including Navy Super Stallions assault helicopters with Marines aboard, were sent to find O’Grady. As the aircraft approached, O’Grady set off an emergency flare, and its yellow smoke guided the Super Stallions to a clearing he had selected. He darted from a hiding place with pistol in hand and fear in his eyes.22 “I’m ready to get the hell out of here,” O’Grady shouted as he was pulled aboard one of the helicopters.23 They were on the ground only a few minutes.

O’Grady was on the Kearsarge within two hours, receiving treatment for minor injuries and dehydration. Word of his rescue soon reached Washington, where it was almost one o’clock in the morning on June 8. Clinton and his national security adviser, Anthony Lake, broke out cigars to celebrate the news.24 Mindful of a ban on smoking in federal buildings, Clinton and Lake lit up out of doors, on the Truman balcony at the White House.25 Later, Clinton placed a call to O’Grady, telling the rescued pilot, “The country was on pins and needles, but you knew what you were doing. The whole country is elated.”26

Clinton, though, was criticized by Democrats and Republicans alike for failing to retaliate against the Serbs for downing a U.S. warplane.27 It was another example, critics said, of the administration’s dithering, incoherence, and fecklessness. Disarray did indeed seem to define Clinton’s foreign policy, on Bosnia especially. Back-pedaling, humiliating setback, and inaction had characterized his administration’s response to major challenges abroad. It was even said that the “commander in chief who avoided the Vietnam draft couldn’t even manage a snappy military salute.”28 Clinton’s foreign policy record in the first years after his election was uninspired.

Intervention in Somalia had resulted in trauma. A humanitarian and peacekeeping mission in Somalia, begun during the closing days of the administration of President George H. W. Bush, was ruined by a bloody ambush in October 1993 in the capital, Mogadishu. Eighteen U.S. servicemen were killed in the firefight while trying to capture the lieutenants of a Somali strongman and clan leader, Mohamed Farah Aideed. The humiliating disaster at Mogadishu, in which the body of a slain U.S. Army Ranger was dragged through the streets, prompted Clinton to announce the withdrawal of U.S. forces. Six months later, the Clinton administration stood by, declining to intervene as extremist Hutus rampaged in Rwanda, massacring hundreds of thousands of their countrymen. Those episodes—especially the debacle in Somalia—had powerful restraining effects on the administration’s Bosnia policy,29 the cornerstone of which was to avoid the deployment of U.S. forces.30

In office, Clinton retreated from promises made on the campaign trail to address the miseries of Bosnia by lifting an arms embargo against Bosnian Muslims and launch airstrikes against Bosnian Serb positions—moves that might have ended the war in 1993.31 Instead, Clinton deferred to the Europeans,32 allowing them to take the lead in attempting to resolve a European conflict. But the Europeans foundered in Bosnia in the face of horrors not seen on the continent since World War II.

O’Grady’s rescue brought a rare moment of cheer from Bosnia, an occasion when Serb forces had been outfoxed and plainly embarrassed.33 But what finally swept away the tentativeness and hesitation of the Clinton administration’s policy on Bosnia was not O’Grady’s deliverance but the worst massacre in Europe in fifty years.34 In July 1995, Bosnian Serb forces under Mladić’s command entered the U.N.-declared “safe area” at Srebrenica, a Muslim enclave in mountainous eastern Bosnia. The Serbs disarmed the hapless and meagerly equipped Dutch peacekeepers35 and launched a cold-blooded orgy of violence. Cruelly, Mladić and his men handed out chocolates to Muslim children, telling them they had nothing to fear. “You’ll be taken to a safe place,” Mladić assured them.36

The Serbs separated Muslim men and boys from women and girls. Over the next several days, more than 8,000 men and boys were killed by execution or ambush.37 Many of them were bound and blindfolded, then shot in the back of the head, their bodies dumped in mass graves. Muslim women and girls were raped. Mothers took desperate measures to keep their daughters from being targeted for sexual assault, dirtying their faces and making them wear peasant clothing so they would appear unattractive.38 Word of the atrocities soon slipped out of Srebrenica, and NATO responded with a few ineffective airstrikes.39 Otherwise, the outside world did little to stop the attacks.40

The massacre at Srebrenica was the single worst atrocity of an evil war,41 and it stirred fierce criticism in the United States about Clinton’s policy of nonintervention. A firestorm arose from the right and the left. William Safire, a conservative columnist for the New York Times, wrote that Clinton would be “remembered in history as a man who feared, flinched and failed,” whose diffidence in the face of “Nazi-style ethnic cleansing” in Bosnia had “turned a superpower into a subpower.”42 Anthony Lewis, who wrote for the New York Times from the left, said the fall of Srebrenica pointed up “the vacuum of leadership in the White House.” Clinton, he wrote, “does not want any change in the world’s response to the Serbs, for a simple reason. Change is likely to mean American ground forces, and Mr. Clinton fears that would be politically damaging to him.”43

Clinton soon recognized, though, that deference and nonintervention in Bosnia were beginning to harm him, politically.44 The fall of Srebrenica and of another U.N. safe area at Žepa in late July 1995 were catalysts for a more assertive American policy45 in which the United States would take the lead in seeking to end the war in Bosnia, coupling diplomacy with the genuine threat of military force. The policy began to take shape in late summer 1995 and would eventually culminate in the remarkable negotiation at Dayton.

Meanwhile, the military equation in Bosnia had slowly begun to shift away from Serb forces. An offensive in early August 1995 by the Croatian army reclaimed the Krajina region, which had been seized by the Serbs early in the war. The Croat offensive uprooted more than 150,000 ethnic Serbs from the Krajina in another spasm of “ethnic cleansing” in which homes were burned and civilians were fired on.46 The United States privately endorsed the offensive because it shifted the dynamics on the ground and made a negotiated settlement somewhat more promising.47 For the first time since the war began, Serb forces were in retreat and appeared vulnerable.

Their vulnerability deepened in August. NATO had warned the Serbs against attacking remaining U.N. safe areas in Bosnia, including Sarajevo. They faced intensive air strikes if they did. Late in the month, Serb forces besieging Sarajevo lobbed five mortar shells into the city, one of which killed thirty-seven people in an open-air market. Within days, U.S. warplanes under NATO authority responded with an aerial bombing campaign on Serb military barracks, ammunition depots, air-defense sites, and communications towers in what was the alliance’s most extensive military action since its founding after World War II.48 In mid-September, the battered Serb forces pulled back their heavy artillery, lifting the siege of Sarajevo after forty-one months. In that time, more than 11,000 people had been killed in Sarajevo, and much of the city had been turned to rubble.

Also in August, Clinton designated Richard Holbrooke, the assistant secretary of state for European and Canadian affairs, as lead negotiator on the U.S. initiative to end the war. The choice of Holbrooke was more than a little controversial. Holbrooke was fifty-four years old and an outsize, colorful, and complex character. He was by turns charming, abrasive, theatrical, and explosive—and seldom disinclined to offer his opinions. It was said that “hubris” and Holbrooke were inseparable.49

Not even his superiors quite knew how he worked or how to control him.50 “I’m not always sure what you are doing, or why,” Secretary of State Warren Christopher told Holbrooke as the talks in Dayton unfolded, “but you always seem to have a reason, and it seems to work, so I’m quite content to go along with your instincts.”51 Holbrooke was given alternately to cajoling, improvisation, and swings of emotion—all of which were on display amid the intensity and uncertainties of the talks at Dayton.52

Holbrooke advocated a muscular kind of diplomacy and recognized the importance of military force in the pursuit of diplomatic objectives. “He was comfortable with American power, Vietnam notwithstanding,” Roger Cohen of the New York Times wrote shortly after Holbrooke’s death in December 2010. “The Balkan bullies, Slobodan Milosevic chief among them, shrank before U.S. military brass; Holbrooke, adept at theater, knew that. . . . He knew how to close and how closing depended on a balance of forces.”53

Holbrooke brought to Dayton the searing recent experience of losing three members of his negotiating team in a roadway accident outside Sarajevo. The mishap happened August 19 as American negotiators traveled a winding, mud-slick road on Mount Igman above Sarajevo, where they were headed for a meeting with Izetbegović, the Bosnian president. Holbrooke was on the same mountain road, in a Humvee ahead of the armored personnel carrier in which Robert C. Frasure, an assistant secretary of state, and the two other Americans were riding. The personnel carrier slipped off the narrow road, rolled over several times, caught fire, and exploded. Along with Frasure, Joseph J. Kruzel, a deputy assistant secretary of defense, and Colonel S. Nelson Drew of the Air Force were fatally injured.

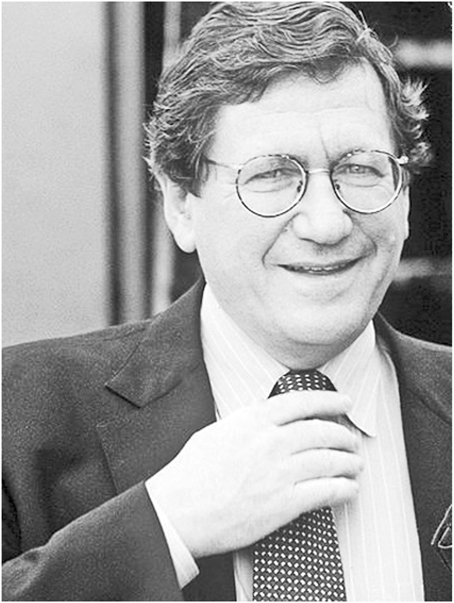

FIGURE 17. Richard C. Holbrooke, a colorful assistant secretary of state, led the U.S. negotiating team at Dayton, Ohio. Holbrooke could be, by turns, abrasive, charming, melodramatic, and explosive. Those tendencies were all in evidence during the three weeks of talks, which frequently teetered on failure. (Photo credit: Charlie Parshley)

They were on Mount Igman because the Bosnian Serbs besieging Sarajevo would not guarantee their safety had they flown into the city’s airport.54 Their deaths were a bitter and shattering blow that interrupted the emergent U.S. diplomatic initiative on Bosnia but did not derail it. Indeed, after funerals in Washington for Frasure, Kruzel, and Drew, Holbrooke and his team returned to the Balkans in a frenetic burst of shuttle-style diplomacy in late summer and early autumn. Later, during the negotiations in November, Holbrooke said publicly that he sensed that Frasure, Kruzel, and Drew were “with us here in Dayton at all times.”55

Holbrooke was at Dayton for the duration of the talks. Christopher was there for the start, for the end game, and twice in between. Holbrooke and Christopher, then seventy years old, made for an odd yet surprisingly complementary team. The secretary of state was an earnest lawyer-diplomat: a bit stuffy, unfailingly courteous, and rarely confrontational. He was an earnest, if mediocre, secretary of state,56 most in his element while negotiating. In contrast to Holbrooke’s urgent manner and tousled appearance, Christopher was restrained and buttoned-up.57 At Dayton, Christopher “played soft cop to tough cop Richard Holbrooke,” as Britain’s Economist magazine observed.58 Christopher’s senior rank within the Clinton administration lent gravitas that impressed the Balkan leaders.59

Dayton was an intriguing if odd choice as the site of the talks. The old factory town was preparing in late 1995 to commemorate its bicentennial. In its 200 years, Dayton had been something of a crucible for invention and innovation. Orville and Wilbur Wright designed their aircraft on the city’s West Side. The cash register was invented in Dayton; so were the pop-top beverage can, the wooden folding stepladder, and the soft-rubber ice cube tray.60 As the Bosnian peace talks began in their city, civic boosters claimed that Dayton had produced more patents per capita than any place in the United States.61 To think of Dayton as a dull city where nothing much ever happened was to be more than slightly mistaken.

Its selection as the venue62 for the talks had nothing to do with its culture of innovation. Dayton was halfway around the world from the Balkans and light years from the ethnic violence there, but it was just an hour’s flight from Washington, D.C., allowing Christopher and other senior U.S. officials reasonably quick access to the talks. “We wanted a place that was far enough away from Washington” so ranking U.S. officials weren’t always present, recalled Donald L. Kerrick, a retired Army general who was the National Security Council’s representative on Holbrooke’s negotiating team. “But we wanted a place close enough [to Washington] so that we could get them there if we needed them.”63

The Wright-Patterson base sprawls over 8,200 acres. Its runways can accommodate jets of any size. The base employed 23,000 people, had a payroll greater than Bosnia’s output,64 and fairly bristled with reminders of U.S. firepower and military readiness—reminders not lost on the Balkan leaders.65 It was a perfect place to conduct a high-stakes negotiation; it ensured seclusion and near-impregnable security. The news media could be kept at a distance, well beyond the high fence of the base, so a news blackout was easy to maintain.

Inside the Wright-Patterson perimeter was the Hope Hotel and Conference Center, named for actor and comedian Bob Hope. About 100 yards away was a cluster of low brick buildings known as the Visiting Officers’ Quarters. Four buildings were grouped around a parking lot, and a fifth building stood nearby. These were turned into the similar-but-separate accommodations for the negotiating teams, housing the delegations from Bosnia, Serbia, and Croatia as well as the U.S. team and representatives from Europe and Russia. The rooms of the Visiting Officers’ Quarters had been remodeled and repainted in the second half of October, and they were virtually identical, down to the lampshades.66 They offered modest comforts and nothing lavish. In style, furnishings, and amenities, the Visiting Officers’ Quarters were more Motel 6 than the Ritz.67

The people of Dayton were engaged by the improbable presence of a major international event in their town.68 They styled their town as the “temporary center of international peace,”69 placed peace candles in their windows, and mostly shrugged off Milošević’s half-joking complaint that he did not want to be cooped up in Dayton like a priest.70 They had only glimpses, though, of what Holbrooke was later to call “an all-or-nothing, high-risk negotiation.”71

The talks opened November 1, 1995, in a brief, tightly choreographed ceremony at the B-29 Super Fortress conference room at the Hope Hotel and Conference Center. “It was a historic gathering,” wrote Roger Cohen, a New York Times correspondent who had covered years of bloodletting in the Balkans. “The walls were off-pink. The plants looked miserable. The furniture was modest. The gray carpet did not quite conceal a stain or two. Versailles it was not.”72 Elegance was absent and awkwardness prevailed. The three Balkan presidents—Izetbegović, Milošević, and Tuđman—entered the conference room, one by one, each escorted by a senior U.S. diplomat serving in his country.73 Only after encouragement from Christopher did the three leaders stand and perfunctorily shake hands for the cameras. They were not permitted by their American hosts to make remarks or speak to the scores of journalists crowding the conference room. And they made little eye contact with one another. They knew each other well, and mutual contempt was open and ran deep. To Kerrick, one of the American negotiators, the Balkan presidents were not unlike members of a Mafia family—they shared some interests but also pursued dissimilar goals and objectives.74

In his remarks, Christopher outlined the hoped-for outcomes of the talks: Bosnia was to remain a single state, “with an internationally recognized border and with a single international personality”; an agreement would have to address the history and significance of Bosnia’s largest city, Sarajevo; human rights throughout the region must be respected and rights-abusers must be punished; and the dispute over the Serb-held region of Croatia’s Eastern Slavonia must be resolved.75 The goals were ambitious and the format of the talks—effectively sequestering leaders and top officials of three sovereign states far from their home countries—was without immediate precedent. The nearest approximation was the Camp David talks in 1978 that produced a peace agreement between Egypt and Israel.76 But the talks at Dayton were more complex by many measures—in the number of participants, certainly, and in the depth of grievances and hatreds represented there. In the internecine warfare in Bosnia, as Richard Sale noted in his book about Clinton’s foreign policy, “Serbs had attacked and fought Croats, Croats had attacked and fought Muslims and vice versa, then both the latter had joined together to fight against Bosnian Serbs.”77

Given all the peculiarities, the Dayton talks were sui generis. Holbrooke called it “the Big Bang approach” to negotiating: “lock everyone up until they reach agreement.”78 These days, the “Big Bang approach” probably would be unsustainable for very long; enveloping negotiations in “radio silence”79—as the Americans insisted on at Dayton80—would be quickly undermined by video and text options that are routinely available on Smartphones and other mobile devices. In the digital century, Dayton would be impossible to duplicate, at least logistically.

In convening the talks, the Americans turned to fairly bleak rhetoric. “If we fail,” Christopher said, “the war will resume and future generations will surely hold us accountable for the consequences that would follow. The lights . . . in Sarajevo would once again be extinguished, death and starvation would once again spread across the Balkans, across perhaps the entire region, threatening the region and perhaps Europe itself. To the three presidents, I say to you that it’s within your power to chart a better course for the future of the people of the former Yugoslavia.”81

The invariably reserved Christopher seemed rather out of character as he invoked a grim prospect of world war should the talks fail. “If the war in the Balkans is reignited,” he said, “it could spark a wider conflict like those that drew American soldiers to Europe in huge numbers twice this century. If the conflict continues, and certainly if it spreads, it would jeopardize our efforts to promote peace and stability in Europe. It would threaten the viability of NATO, which has been the bedrock of European security for 50 years. If the conflict continues, so would the worst atrocities that Europe has seen since World War II.”82 No small measure of pessimism lurked behind the stern rhetoric. “I don’t think anybody really thought we would succeed,” Kerrick recalled.83 There was ample reason for such gloom. No fewer than four international peace initiatives had failed in the years before Dayton. Bosnia seemed to defy diplomatic resolution.

Even so, a good deal of provisional understanding had been reached in the weeks before the Dayton talks began, as Holbrooke and his negotiating team shuttled through the Balkans. It was understood in principle that Bosnia would remain a single state with two self-governing entities—a federation of Muslims and Croats, and a republic of ethnic Serbs, called Republika Srpska. Fifty-one percent of Bosnia’s land mass would be federation territory; forty-nine percent would be held by ethnic Serbs, a division that roughly reflected the confrontation lines at the time of the ceasefire in October 1995. It was further understood that a peace agreement would be policed by 60,000 NATO-led peacekeepers, including 20,000 U.S. troops—a controversial provision that polls indicated most Americans opposed.

Nonetheless, many issues awaited resolution at Dayton, including how Sarajevo would be governed, how suspected war criminals would be dealt with, what authority the peacekeeping force would have, and how the proposed Muslim-Croat Federation would function. The major impediment was in determining boundary lines for the 51/49 territorial split within Bosnia between the federation and the Serb republic.84 U.S. delegates on the first night of the talks distributed draft copies of what they called the “Framework Agreement,” along with several annexes.85 It was clear soon enough that the negotiations would be a hard slog. The pace of the talks was languid, and the first week at Dayton brought no notable movement on the toughest issues.86 “All going well, just unclear where all is going,” Kerrick wrote in a memorandum to Anthony Lake, Clinton’s national security adviser, at the close of the first week of talks.87

The following day, U.S. negotiators convened what essentially was a plenary on territorial issues and the governance of Sarajevo. It was a six-hour waste of time.88 “Despite hours of heated, yet civil exchanges, absolutely nothing was agreed,” Kerrick wrote afterward. “Astonishingly, at one moment [the] parties would be glaring across [the] table, screaming, while minutes later they could be seen smiling and joking together over refreshments.”89 Never again did the U.S. team call such a meeting. Instead, the Americans pursued the negotiations mostly by shuttling among the respective Balkan delegations.90

The first days at Dayton were embroidered by a notably surreal moment and by a major distraction. The surreal moment came during a dinner for all delegates that the Americans threw at the Air Force Museum at Wright-Patterson—a cavernous venue that Holbrooke called “the greatest military air museum in the world.”91 An Air Force band played Glenn Miller music as delegates dined in the shadows of a huge B-29 heavy bomber, several Stealth F-117 fighters, and, “appropriately to some, a Tomahawk cruise missile that seemed pointed right at Milošević’s table,” Derek Chollet wrote in his account of the Dayton talks.92 Kerrick recalled during the dinner that he looked up at the cruise missile and pointed it out to Milošević. “I said, ‘Mr. President . . . we have a lot of those.’”93

The distraction was created by the Bosnian Serbs’ jailing of David Rohde, a reporter for the Christian Science Monitor. Rohde, who was twenty-eight years old, had rented a red Citroën automobile in Vienna and driven to Bosnia, seeking to investigate the killing ground at Srebrenica, from where he had reported a few months earlier. He was arrested and accused of being a spy.94 Holbrooke, who later observed that Rohde showed “more courage than wisdom” in going to Srebrenica without papers or permission,95 insisted on the journalist’s release, telling Milošević that no agreement was possible at Dayton until Rohde was set free.96 “We are pressing this hard,” Holbrooke wrote in a memorandum at the close of the first week of talks.97

Despite the news blackout, journalism had intruded at Dayton.98 With Holbrooke at Dayton was his wife, the writer Kati Marton, who was chair of the Committee to Protect Journalists, an advocacy organization based in New York. She, too, pressured Milošević for Rohde’s release.99 The Serbs finally gave in, and on November 8, ten days after he was arrested, Rohde was taken to Belgrade and turned over to officials at the U.S. embassy. For years afterward, Holbrooke ribbed Rohde for having complicated the Dayton talks.100 Which he had.101

More powerful rhythms were at work at Dayton. After ten days, a kind of high-tide, low-tide pattern emerged in the talks. Kerrick mentioned this in a memorandum to Anthony Lake. He wrote that the parties were “enjoying each other’s company, but [the] more they see of each other [the] more they seem to be willing to chuck it all and return to war.” Every twelve hours, Kerrick added, seemed to bring a sense of certain failure, “only to find real chances for success at the next high tide.”102 Progress had been made on a number of issues, including the structure of the Muslim-Croat Federation and a timetable for the Croats to regain Eastern Slavonia. But the most contentious issues, including political control of Sarajevo and the boundaries of the 51/49 territorial split, remained unsettled.

A modest opening on Sarajevo developed during a lunch at the Wright-Patterson officers’ club; Chollet called it “napkin diplomacy.” At one end of the club’s wood-paneled dining room, Holbrooke took lunch with Milošević. At a table at the other end of the room was Haris Silajdžić, the Bosnian prime minister. Holbrooke at one point walked to Silajdžić’s table to say hello and fell into discussion about establishing a land corridor from Sarajevo through Bosnian Serb territory to Goražde, a Muslim enclave in eastern Bosnia. Silajdžić outlined some options on napkins, which Holbrooke took across the room and handed to Milošević. After a number of similar trips back and forth, Holbrooke brought Silajdžić to his table, to include Milošević in the discussion. Milošević suggested that Bosnian Muslims deserved to govern Sarajevo, considering how they had withstood Bosnian Serb shelling for more than three years. Nothing was settled, but “napkin diplomacy” signaled the start of a serious negotiation about territorial questions.103

That night, Holbrooke renewed the discussions about the corridor, seating Milošević in front of a classified, three-dimensional simulation apparatus called “PowerScene.” The device cost some $400,000 and had been used a couple of months before to select targets during the NATO-led bombing of Serb positions in Bosnia.104 PowerScene was a joystick-driven imaging device that offered high-resolution views of Bosnia’s topography. It was installed in the American delegation’s quarters, in what came to be called the “Nintendo Room.” Milošević was enthralled. The PowerScene images of Bosnia’s landscape showed unmistakably that a land corridor two miles wide from Sarajevo to Goražde, as Milošević had proposed, would be untenable. After a few hours of PowerScene-driven overflights, as well as discussions lubricated by Scotch, Milošević agreed to a land corridor five miles wide.105 “We have found our road,” he said, draining his glass.106 Inevitably, perhaps, the corridor was informally called “Scotch Road.”

The “Scotch Road” deal represented movement, but a comprehensive agreement was still elusive, and the Americans set a deadline of midnight Sunday, November 19. They said they would close the negotiations, one way or the other, at that time.107 Forcing the delegations to confront a deadline, the Americans figured, could have the salutary effect of concentrating attention, which tended to stray at Dayton. “These people had fought one another for a long time,” Holbrooke later noted, “and were ready to sit in Dayton for a long time and just argue.”108

As the talks had gone on, contrasts among the respective delegations became sharper. Tuđman, the Croat leader, had secured concessions on Eastern Slavonia, his major objective at Dayton. After that, he was mostly aloof. The Bosnian delegation headed by Izetbegović was plagued by internal tensions and disputes, and seemed ambivalent about reaching a deal.109 The American negotiators grew increasingly frustrated with the Bosnian officials, whom they privately referred to as Izzy, Silly, and Mo110—for Izetbegović, Silajdžić, and Muhamed Sacirbey, the foreign minister. The Bosnians rarely acted in concert, and differences among them were too often apparent. They “continue to amaze us all with their desire to torpedo one another—and possibly even peace,” Kerrick wrote as the talks ground on.111

The cold-eyed Milošević was the Balkan leader most eager for a deal. He knew that the ruinous international economic sanctions imposed on Serbia would be lifted only if the Dayton negotiations produced a peace agreement. That reality—and a related if unrealistic yearning to rehabilitate his reputation112—guided Milošević’s conduct at Dayton. “I think he had a grander vision for Serbia that he knew he couldn’t [achieve] without a peace agreement,” said Kerrick. “He really wanted, I think, to walk the streets of New York and be seen as a guy who brought peace to Yugoslavia.”113 Milošević of course neither won nor deserved such respect. He was indicted in 1999 for crimes against humanity, turned from power in 2000, arrested in Belgrade in 2001, and sent to trial at The Hague.

At Dayton, though, the Americans found him to be engaging, accessible, flexible, and savvy. He effectively sidelined the Bosnian Serb representatives and treated them with contempt. They lurked at the fringes of the talks, suspicious of what was going on but kept in the dark, and mostly ignored.114 In the decisive moments at Dayton, it was Milošević who made the concessions.

On the eighteenth day of the talks, Milošević unexpectedly capitulated and conceded control of Sarajevo to the Muslim-Croat Federation. He rejected a partitioned city or a federalized solution, à la Washington, D.C. “Izetbegovic has earned Sarajevo by not abandoning it,” Milošević told the Americans. “He’s one tough guy. It’s his.”115 It was a major and surprising concession. Taking Sarajevo had been a major objective of the Bosnian Serbs since the war began, and now, astoundingly, Milošević was giving it away. He subsequently agreed to give up the Serb-controlled suburbs of Sarajevo as well.116

Ironically, the concessions on Sarajevo and on the land corridor to Goražde had complicated the task of establishing the 51/49 territorial split. Milošević’s concessions on Sarajevo and the Goražde corridor had altered the ratio to 55/45. To achieve the 51/49 split, the Muslims and Croats would have to cede territory to the Bosnian Serbs.117 The prospect was not an agreeable one.

Matters looked bleak indeed as the midnight deadline approached on November 19, and Holbrooke asked for a look at the so-called “failure statement” that the Americans had prepared as a contingency and would release should the talks break down. Holbrooke looked it over and found it too tepid. It is not “final” enough, he said, tossing the statement into the air. As the pages fluttered down in the Americans’ conference room, the chief U.S. negotiator began dictating a blunt and more downbeat statement to the State Department speechwriter, Tom Malinowski. This remarkable, late-night scene was recounted by Chollet in The Road to the Dayton Accords:

Standing over a computer, a visibly tired and agitated (and some thought crazed) Holbrooke dictated the language to Malinowski while the other Americans looked on in astonishment. His redraft reflected the frustration of the moment. “To put it simply,” his statement concluded, “we gave it our best shot. By their failure to agree, the parties have made it very clear that further U.S. efforts to negotiate a settlement would be fruitless. Accordingly, today marks the end of this initiative . . . the special role we have played in recent months is over. The leaders here today must live with the consequences of their failure.”118

The high-tide, low-tide dynamic that Kerrick had noted a few days earlier soon reasserted itself. As Holbrooke reworked the draft failure statement, Milošević and Silajdžić were meeting to discuss ways of achieving the 51/49 territorial split. They landed on an idea of ceding an egg-shaped swath of thinly populated, mountainous territory in western Bosnia to the Serbs. It would be enough to reach the 51/49 division. They went to the American conference room to describe their handiwork. It was about 4 a.m. and, suddenly, resolution of the major obstacle of the negotiation seemed at hand. Christopher, who had returned to Dayton for the end of the talks, took a bottle of California white chardonnay wine from his private reserve and opened it to toast the apparent breakthrough.119

Izetbegović was summoned, and the Bosnian president arrived wearing a coat over his nightshirt. He seemed cool to the tentative deal. The Croat foreign minister, Mate Granić, also was awakened and called to the conference room. He immediately asked to see the map showing the territorial division that Milošević and Silajdžić were proposing. Granić scanned it and exploded. “Impossible, impossible,” he shouted. “Zero point zero zero percent chance my president [Tuđman] will accept this!”120 Silajdžić had proposed to give away land that the Croat military had won in the summer offensive, and Croat officials would have none of that. Izetbegović spoke up, saying he would side with his nominal Croat allies and oppose the compromise that Silajdžić, his country’s prime minister, had developed with Milošević. Silajdžić glared at Izetbegović and stormed from the conference room, shouting, “I can’t take this anymore.”121 The deal had lasted all of thirty-seven minutes.

The Americans’ midnight deadline had long since passed, and Holbrooke and Christopher agreed to give the talks one more day. Progress had been made on many other issues, and they asked Clinton to weigh in on the 51/49 conundrum. The president telephoned Tuđman, encouraging him to cede the territory needed to reach the 51/49 split. Tuđman was willing, but the Bosnians also would have to give up some territory for a deal to be struck. The Bosnians seemed reluctant. Finally, late on November 20, Christopher presented Izetbegović with an ultimatum: accept the revisions for the 51/49 split as well as the other agreements reached at Dayton, or the talks would be over. Raising his voice as he seldom did, Christopher told Izetbegović that almost everything the Bosnians had sought had been achieved in the talks.122 He gave Izetbegović an hour to decide.

Shortly before midnight, Izetbegović sent word that the Bosnians would yield enough territory to the Serbs to close the deal—provided that Brčko, a strategic town in northeast Bosnia, be included in the Muslim-Croat Federation.123 This was a new and thoroughly unwelcome eleventh-hour demand. The town stood astride a narrow corridor that connected the western and eastern segments of the Serb republic in Bosnia. Brčko’s fate, as far as the Americans were concerned, had already been decided: the Serbs were to have it.124 The demand for Brčko, Christopher thought, was at last the deal-breaker: he suspected Milošević would never accept Izetbegović’s demand and further suspected the Bosnians wanted “to avoid coming to grips with the end game” at Dayton.125 In other words, they were not opposed to the talks ending in collapse.

In the early hours of November 21, Christopher went to bed thinking the talks were on the brink of failure.126 The failure statement—revised and toned down from Holbrooke’s draft of twenty-four hours earlier—was distributed to the Bosnians, Croats, and Serbs.127 Milošević was incredulous, telling the American representatives who delivered the statement: “You’re the United States. You can’t let the Bosnians push you around this way. Just tell them what to do.”128 No, they told him, it is up to you to bring the others around.129

Not long after sunrise on the snowy morning of November 21, Milošević went to see Tuđman, suggesting the Serbs and Croats sign a peace agreement at Dayton while allowing the Bosnians to sign later. Such a tactic, Milošević figured, would exert great pressure on Izetbegović and the Bosnian team. Milošević went to the U.S. quarters to present the idea. He arrived just as Holbrooke had convened what was to be the delegation’s close-out meeting. He and Christopher broke away from the meeting to speak privately with Milošević. An agreement without endorsement of all parties was impossible, they told him. If a three-way deal agreement could not be concluded, the talks would be shut down.130 In any case, Christopher said, a two-sided deal would not be legally binding.131

Milošević had a final card to play: he proposed sending the question of Brčko’s sovereignty to international arbitration. Once again, Milošević had yielded. In doing so, he cleared away the last obstacle to a deal. Holbrooke and Christopher took the arbitration proposal to Tuđman, who backed it, saying, “Get peace. Get peace now! Make Izetbegovic agree.”132 The Americans went to the Bosnians’ quarters, outlined Milošević’s offer, and demanded an immediate answer. After a lengthy pause, Izetbegović spoke, saying it was not a just peace “but my people need peace.” Which meant he had at last agreed.133 Fearing that the Bosnians might again raise fresh demands, Holbrooke whispered to Christopher, “Let’s get out of here fast.”134 They called Clinton with the news of a deal, and shortly before noon on November 21, the president stepped into the Rose Garden to announce the agreement. “American Exceptionalism” infused his remarks, especially those devoted to the deployment of 20,000 American troops as part of the international peacekeeping force to go to Bosnia. Clinton declared:

Now that the parties to the war have made a serious commitment to peace, we must help them to make it work. All the parties have asked for a strong international force to supervise the separation of forces and to give them confidence that each side will live up to their agreements. Only NATO can do that job. And the United States as NATO’s leader must play an essential role in this mission. Without us, the hard-won peace would be lost, the war would resume, the slaughter of innocents would begin again, and the conflict that already has claimed so many people could spread like poison throughout the entire region. We are at a decisive moment. The parties have chosen peace. America must choose peace as well.135

The Dayton accords—known formally as the “General Framework Agreement for Peace in Bosnia and Herzegovina”—covered 165 pages and included 12 annexes and 102 maps. It was comprehensive, or nearly so, embracing the 51/49 territorial split between the Muslim-Croat Federation and Republika Srpska.136 It also affirmed Bosnia’s international borders, set forth a constitution for the country, and specified that people displaced by the war could return to their homes. It established a central bank and single currency, and it obliged the parties to abide by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, which had been established at The Hague in 1993. The agreement would be enforced by an Implementation Force (or IFOR), consisting of 60,000 NATO-led troops, one-third of whom would be American.

The three Balkan leaders initialed the accords on the afternoon of November 21 in the B-29 Super Fortress conference room where the talks had begun so awkwardly three weeks before. Clinton thought of traveling to Dayton to attend the initialing ceremony, but Holbrooke dissuaded him, saying, “You don’t want to be anywhere near these people today. They are wild and they don’t deserve a presidential visit.”137

The accords were signed in mid-December at Elysée Palace, the official residence in Paris of the French president. In a bit of Gallic pique, the French Foreign Ministry referred to the agreement as the Treaty of the Elysée and, according to Holbrooke, asked speakers at the signing ceremony “to omit any references to Dayton in their remarks.”138 As Holbrooke noted, the Dayton accords had shaken “the leadership elite of post–Cold War Europe” and “some European officials were embarrassed that American involvement had been necessary” to bring the Bosnian conflict to a close.139 Izetbegović, Milošević, and Tuđman played to form in Paris. “There were no tears of relief, no emotional scenes of reconciliation” from any of them, the New York Times reported. “They signed without saying a word, put the caps back on their fountain pens and shook hands perfunctorily.”140 The treaty, Izetbegović said, was akin to swallowing bitter medicine.141

FIGURE 18. Three Balkan presidents initialed the Dayton peace accords on the afternoon of November 21, 1995, hours after the talks were rescued from collapse. The leaders were, seated from left, Slobodan Milošević of Serbia, Alija Izetbegović of Bosnia, and Franjo Tuđman of Croatia. (Photo credit: Brian Schlumbohm)

The Dayton accords in many ways reflected the complexities, fragility, and contradictions that define the Balkans. The agreement was not without serious shortcomings; its flaws were unmistakable. It was, notably, inherently contradictory, containing elements that encouraged integration of Bosnia’s ethnicities as well as elements that served to drive them apart. The fundamental tension lay in the fact that the accords established a weak central government and two semi-autonomous entities shaped by ethnicity. Both entities—the Muslim-Croat Federation and the Republika Srpska—were granted their own governing structure, parliament, police force, and state agencies. To critics, that looked a lot like partition beneath the fig leaf of a weak unitary government.142 It hardly seemed to be a formula for developing a thriving, multiethnic state.

Moreover, the agreement rewarded Bosnian Serb aggression. Republika Srpska controlled just under half of the territory of Bosnia; before the war, the Serbs had controlled about a third of Bosnian territory. The Dayton accords also permitted the three once-warring parties in Bosnia to retain their respective armies.143 One country, two entities, three armies: these, too, were hardly the ingredients of a sturdy peace. Ted Galen Carpenter, a foreign policy expert at the Cato Institute, a libertarian think tank in Washington, D.C., wrote that the “American-inspired peace plan is one of those convoluted enterprises that habitually enchant diplomats but have no connection to reality.”144 He further wrote that a Bosnia “with two political heads may be theoretically innovative, but it is utterly impractical.”145 In fact, the Bosnian state could be said to have three political heads: a three-person presidency that included two members from the Muslim-Croat Federation and one from the Serb republic. “American diplomacy kept Bosnia whole,” said one critic, “by stitching it together like Frankenstein’s monster.”146

Nevertheless, the foremost priority of the Dayton negotiations had been to end the bloodshed in Bosnia, and in that central objective the talks were a success147—perhaps even “a remarkable achievement,” as Stephen Sestanovich has written.148 A war that claimed 100,000 lives has not flared again. A peace that seemed wobbly, even coerced, has held. That outcome can be attributed in measure to the presence of the NATO-led IFOR contingent in Bosnia. IFOR included 20,000 U.S. troops, and sending them to Bosnia represented for Americans the single most controversial element of the Dayton accords.

A clear majority of Americans opposed committing U.S. forces to Bosnia as part of the IFOR peacekeeping force.149 The Pentagon was not enthusiastic about the troop deployment, either, fearing that Bosnia could turn into a bloody quagmire, akin to that of Vietnam.150 “In their hearts,” Holbrooke wrote, “American military leaders would have preferred not to send American forces to Bosnia.”151 Large numbers of body bags, Holbrooke later said, “had been prepared for the casualties that the Pentagon believed were certain to come” in Bosnia.152

In addressing the unease about troop commitments to Bosnia, Clinton turned again to “American Exceptionalism.” He did not invoke the phrase, but his meaning was clear enough. In a televised address at the end of November, Clinton dismissed arguments that the United States had no vital interests in the Balkans and promised that the U.S. troop deployment would be “limited, focused, and under the command of an American general. In fulfilling this mission,” the president said, “we will have the chance to help stop the killing of innocent civilians . . . and at the same time to bring stability to central Europe—a region of the world that is vital to our national interests. It is the right thing to do.”153 American leadership, he said, had “created a chance to secure the peace and stop the suffering” in Bosnia. “Securing peace in Bosnia will also help to build a free and stable Europe. Bosnia lies at the very heart of Europe, next door to many of its fragile new democracies and some of our closest allies.”

If U.S. troops were not deployed to help keep the peace in Bosnia, Clinton said, then NATO “will not be there. The peace will collapse, the war will reignite, the slaughter of innocents will begin again. A conflict that already has claimed so many victims, could spread like poison throughout the region, eat away at Europe’s stability and erode our partnership with our European allies. And America’s commitment to leadership will be questioned, if we refuse to participate in implementing a peace agreement we brokered right here in the United States.”154 Clinton acknowledged that the United States “can’t do everything” to keep peace in the world, “but we must do what we can. There are times and places where our leadership can mean the difference between peace and war and where we can defend our fundamental values as a people and serve our most basic strategic interests.” There are, he said, “still times when America and America alone can and should make the difference for peace. The terrible war in Bosnia is such a case. Nowhere today is the need for American leadership more stark or more immediate than in Bosnia.”155

Clinton closed by saying that the “people of Bosnia, our NATO allies and people all around the world are now looking to America for leadership. So let us lead. That is our responsibility as Americans.”156 It was not necessarily an electrifying speech, not a rousing statement of doctrine. Nor was it Kennedyesque in pledging that America would “pay any price, bear any burden, [or] meet any hardship.” But the speech was striking for its unmistakable if tacit embrace of “American Exceptionalism” and for its assertion of muscularity in U.S. foreign policy. It signaled a renewed interventionist ethos for the United States as the “indispensable nation.”157 Clinton invoked that sentiment on other prominent occasions—in accepting the Democratic Party’s nomination for a second term, for example,158 and in celebrating his reelection to the presidency.159 Madeleine Albright, who succeeded Christopher as secretary of state in Clinton’s second term, was even more assertive in her rhetoric, declaring in 1998: “We are the indispensable nation. We stand tall. We see further into the future” than other countries.160

In some respects, to assert “American Exceptionalism” in 1995 was to assert the obvious: the United States was no longer confronted by a rival superpower; the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 had left a world in which the United States, alone, could project military might around the globe.161 Still, the memories of the quagmire of Vietnam and of the more recent disaster in Somalia placed a significant brake on U.S. interventions. Vietnam and Somalia, as Holbrooke noted, still “hung like dark clouds over the Pentagon.”162 They created what he referred to as the “Vietmalia syndrome,”163 a decided reluctance to commit U.S. forces to distant lands. U.S. casualties were a dread prospect, which served in 1995 to restrain American ambitions and interventions abroad.

U.S. forces began deploying to Bosnia at the end of 1995 as part of the IFOR contingent. The U.S. troop presence was supposed to last a year. As it turned out, the last U.S. troops did not leave Bosnia until 2004.164 During that time, there was not one U.S. fatality in hostile action in Bosnia—a wholly unanticipated outcome.165 The feared quagmire did not open in Bosnia, and that country was not again convulsed by war.

Still, IFOR was roundly criticized for having stood by in March 1996 as Bosnian Serb thugs evicted fellow Serbs from homes and apartments in Serb-populated suburbs and enclaves of Sarajevo before they were to come under the jurisdiction of the Muslim-Croat Federation. “We must not allow a single Serb to remain in the territories which fall under Muslim-Croat control,” declared the head of the Bosnian Serb Resettlement Office.166 The disaster, Holbrooke wrote, “could have been easily prevented if IFOR had taken action.”167

An even greater failure was the reluctance of NATO forces to seek out and arrest suspected war criminals such as Mladić and Radovan Karadžić, Bosnian Serb leaders indicted in 1995 for war crimes in Bosnia. Mladić and Karadžić were “most vulnerable after Dayton,” Holbrooke wrote in 2005, “but the opportunity [to arrest them] was essentially lost after the NATO commander in Bosnia, U.S. Admiral Leighton Smith, told Bosnian Serb television, ‘I don’t have the authority to arrest anybody.’” Smith’s statement, according to Holbrooke, was “a deliberately incorrect reading of his authority” under the Dayton accords.168 Mladić remained a fugitive until Serbian police caught up with him in 2011; Karadžić was at large until 2008, when he was captured in disguise in Belgrade, where he had worked as a doctor. Like Mladić, Karadžić is on trial at The Hague for war crimes.

Some analysts have argued that the Bosnian war was ended not so much by the imaginative and assertive U.S. diplomacy as by the sheer exhaustion of the warring parties. “The true lesson of Dayton is this,” journalist Michael Goldfarb wrote in 2010. “When it comes to conflict resolution the United States is still the indispensable, international head cracker—but only when people are too tired to feel the pain.”169 The exhaustion thesis is appealing but untenable. Croat and Muslim forces were resurgent in the summer of 1995, reclaiming hundreds of square miles of territory that had been taken by Bosnian Serbs during the war’s early days. Before the ceasefire took effect in October 1995, a joint Croat-Muslim offensive had threatened the Serb stronghold of Banja Luka.170 An attack on the city never developed. But had it fallen, all of Serb-held western Bosnia was at risk. So Bosnia’s warring parties were hardly played out by late summer 1995. Indeed, a persuasive case can be made that the pre-Dayton ceasefire halted the Croat-Muslim advances prematurely. Moreover, some of the war’s most grievous atrocities—the massacre at Srebrenica, the deadly mortar attack on Sarajevo, and the “ethnic cleansing” of Serbs rousted by Croat forces from the Krajina—all occurred within a few weeks in the summer of 1995. Another year of war, wrote Carl Bildt, a former Swedish prime minister, probably would have been “even more brutal and horrific than the terrible year of 1995.”171

Dayton is more accurately understood as the first major successful foreign policy initiative of Clinton’s presidency.172 After the fiasco in Somalia and the mortification of standing aside as genocide swept Rwanda, the Clinton administration finally found its bearings and a formula: robust if measured application of U.S. military force, especially air power, could be instrumental in ending conflict and in pursuing policy objectives.173 Although Clinton certainly can be faulted for diffident and ineffective responses to attacks by Islamist extremists on U.S. interests abroad during the late 1990s, his foreign policy after Dayton was noticeably more aggressive. The Dayton accords led Clinton to realize, as Kerrick said, that the United States sometimes had to put its “power and prestige on line to do things.”174

Success in ending the brutal war in Bosnia was bracing. It emboldened U.S. foreign policy,175 helped shake off the “Vietmalia syndrome,” rekindled “American Exceptionalism,” and fired ambitions abroad. Bosnia was the first in a succession of ever-more ambitious military operations overseas.176 As Richard Sale has observed, after the first years of his presidency, Clinton “was not in the least dainty about using force.”177 In December 1998, Clinton ordered an extensive four-day bombing of Iraq to punish Saddam’s regime for failing to cooperate with U.N. inspectors investigating the country’s suspected stocks of chemical and nuclear weapons.178 Clinton at that time was about to be impeached on charges of lying under oath and obstructing justice, upshots of a sex scandal discussed in the next chapter. The timing of the bombing campaign stirred suspicions that the attacks were principally a diversion from Clinton’s serious troubles at home.

Britain joined the attack on Iraq, a campaign that was undertaken without U.N. endorsement. The objective was to degrade Iraq’s capacity to produce weapons of mass destruction and to weaken Saddam’s grip on power.179 Six weeks before the bombing, Clinton signed the “Iraq Liberation Act of 1998,” which committed the United States to supporting efforts to remove Saddam and “promote the emergence of a democratic government” in Baghdad.180

Less than a year later, Clinton ordered the bombing of targets in Serbia to pressure Milošević to end the persecution of ethnic Albanians in the province of Kosovo. After more than ten weeks of NATO air strikes, Milošević gave in and withdrew Serbian troops from Kosovo, a first step toward the province’s gaining political independence. The brief Kosovar War was won without U.S. casualties and fought without U.N. approval.181 It was, in some ways, a preemptive war—a war “justified less by what Milošević had already done in Kosovo than by what Americans believed he would do there in the future, judging by his behavior” in Bosnia, Peter Beinart observed in The Icarus Syndrome, his discerning book about trends in U.S. foreign policy.182 Moreover, Beinart wrote, the war in Kosovo “nudged open an intellectual door, a door George W. Bush would fling wide open four years later,” in invoking preemption as a justification for the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq.183

Post-Dayton interventionism—and a willingness to deploy U.S. military power in pursuit of foreign policy objectives—lived on after the Clinton administration. As Derek Chollet and James Goldgeier have noted, “Clinton’s policies and the George W. Bush administration’s ideas about using military power to defend values [overlapped] more than many Americans have perceived, or partisans on both sides care to admit.”184 Both administrations were willing to apply that power without securing prior endorsement of the United Nations.

U.S. foreign policy was decidedly more activist after Dayton: it was embroidered by “American Exceptionalism” and accompanied by what Beinart has termed a “hubris bubble” that expanded as military success encouraged even more ambitious undertakings. “The more confident America’s leaders became in the hammer of military force,” Beinart wrote, “the more closely they looked for nails” in projecting force abroad.185 Bush administration officials were hardly enamored of Clinton, but, “when it came to foreign policy,” Beinart noted, “they stood on his shoulders.”186 The “hubris bubble” expanded with the swift destruction of the Taliban regime in Afghanistan after the devastating September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks on the United States. In 2003 came the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq. In his book about the Bush administration, New York Times reporter Peter Baker anonymously quoted an official in the administration as saying: “The only reason we went into Iraq . . . is we were looking for somebody’s ass to kick. Afghanistan was too easy.”187

The “hubris bubble” burst in the aftermath of the invasion of Iraq. After taking Baghdad and toppling Saddam’s Baathist regime, the United States was thoroughly unprepared for the grinding insurgency that followed. The puncturing of the “hubris bubble” did not necessarily foreclose American ambitions abroad. But it led to a decided retrenchment. As if chastened, the United States in recent years has been far less inclined to apply force to diplomacy and far more content to lead from behind. Twenty years after Dayton, “muscular” is seldom invoked to describe U.S. diplomacy. The “American Exceptionalism” that embroidered the post-Dayton rhetoric of the Clinton administration has fallen decidedly out of fashion among policymakers—a subject of wincing discomfiture and scorn,188 if seriously mentioned at all.189

Holbrooke left the State Department three months after the Dayton accords, saying he wanted to spend more time with his wife and family. He came to regret the decision, saying later that he realized “too late that I had left too early.”190 His departure removed a singular force for implementing the terms of the Dayton agreement. But he returned to the Clinton administration as special envoy to the Balkans and later became U.S. ambassador to the United Nations. He also served two mostly unhappy years in the administration of President Barack Obama as a special representative for Afghanistan and Pakistan,191 a post he held at his death, after emergency surgery for a torn aorta in 2010.192

Dayton was Holbrooke’s major achievement in public life; he relished the accomplishment and kept a dutiful watch on postwar Bosnia.193 He also was known to overstate the significance of the agreement, asserting for example that, without the Dayton accords, al-Qaeda might have planned the terrorist attacks of September 2001 from a safe haven in Bosnia instead of Afghanistan.194 That is a highly debatable, speculative, and in the end an unlikely thesis. The Dayton agreement did require the removal of some 3,000 Islamist fighters who entered Bosnia from Afghanistan, Iran, and Arab countries to join Muslim forces. These fighters constituted a battalion that was disbanded in 1996.195

It is highly improbable that al-Qaeda militants would have operated in Bosnia as freely as they had in Afghanistan before 9/11. Had the talks at Dayton failed and fighting resumed in Bosnia, Islamist extremists surely would have drawn the attention of Serb and Croat forces.196 Moreover, Bosnia’s Muslim leaders were moderate and had shown little affinity for radical Islam. They would have been less-than-eager hosts to an al-Qaeda affiliate in the Balkans.