EIGHT

The Legend Begins

The rising sun sparkled on dew-drenched leaves as Weiser made his way east out of the Bradshaw Mountains. Mid morning, he stopped to water his horse and mule. As he studied his reflection in the stream, signs of middle age no longer bothered him. They suited the seasoned and successful man he’d become. In fact, he thought, they gave dignity to the wealthy man he’d become. He imagined Wells and Fargo begging him to take a seat on their board of directors, and winked at his mirrored self.

But as he rode, prudence told him his move to San Francisco had better wait until he was reasonably certain Waltz’s murder wasn’t going to be found out. The world of prospecting was small enough to ask where his long-time partner was if he showed up in San Francisco alone, with a boatload of gold from an unknown source.

“So what am I going to do?” Weiser asked himself. And the obvious answer was to hide out in nearby Phoenix, a one-horse town where he could pretend to be Waltz until it was safe to move on. It would be far easier to play the part of Waltz than to defend his own highly suspicious actions and predicament.

Phoenix was little more than a hick town on the banks of the Salt River when Weiser arrived. And it was easy to find plots of land available to homestead. He’d known Waltz so long, it was easy to start thinking and behaving like he would have. Accordingly, Weiser chose a plot at the edge of town, with a nice grove of acacia trees and enough land to raise a few chickens and sell their eggs. And it had the advantage of being on the river.

Two weeks after he’d pitched his tent on his new property, Weiser decided it was time to get his new gold assayed.

Tom McCormick’s general store had most of what he needed. And as Weiser’d expected, McCormick examined his small nugget with a jeweler’s loupe and plunked it on a scale.

Hoping to get a clue to the location of Weiser’s strike, McCormick put aside his loupe, peered keenly at Weiser, and said, “I been assaying a lot of years, mister, an’ I ain’t never seen any nugget like this one in these parts.”

Weiser met McCormick’s gaze with a grin and said, “I guess you’d like me to tell you where I found it, Mr. McCormick, but I sure as hell ain’t going to.”

“You can’t blame a fellow for trying,” McCormick said. “Especially since your nugget is the richest I ever seen, Mr. ...?”

“Waltz,” Weiser replied, without hesitating. “Jacob Waltz.”

Six months later, Weiser had a small adobe house on his property and enough chickens to pay for his other groceries. He also had a cache of gold from his new strike buried beneath his hearth.

One lazy afternoon, he was awakened from his afternoon siesta by a couple of Mexicans poking around near his house. He knew who they were all right; they’d come along the day before and put up a canvas tent between his house and the river, ruining his view. “Goddamn Mexicans must be after my gold,” his paranoia whispered.

He’d left his shotgun loaded with buckshot resting against the wall just inside his door. Getting to his feet, Weiser picked up his shotgun, threw open his door, and shot one of the intruders with both barrels. Blood rushed from the man’s chest and he fell, mortally wounded.

The second Mexican turned and ran away before Weiser could reload.

It wasn’t long before word of the shooting made its way to the sheriff. Weiser was ready when the sheriff came out to investigate. Looking the sheriff straight in the eye, he swore he had nothing to do with the shooting. “I heard them Mexicans arguing,” he said. “They woke me up from my nap. Right after that, I heard my door open, two shots, an’ footsteps runnin’ away. I didn’t want to get shot, so I stayed in my house until you got here, Sir.”

Weiser thought he had successfully put the matter to rest with his quick thinking. But the Arizona Gazette ran an article based on his story and the sheriff posted a reward for the missing Mexican. In spite of the $100 reward, the Mexican stayed missing. But Weiser’s assumed identity was now recorded for posterity.

After this incident, rumors of Weiser’s — or, as he was now known, Waltz’s — gold spread like wildfire, making him more famous than he would have liked. And although he’d shed his accent years earlier, his assumed name of Waltz led people to refer to him as “the Dutchman.” And now he had an even bigger problem: with so much publicity for “Waltz,” he could never hope to explain the real Waltz’s disappearance. Moreover, if he went to see Wells and Fargo, he would be in a world of trouble when people started adding up all the clues and coming up with murder.

The bottom line, for the foreseeable future, was he was stuck in Phoenix, and stuck as Waltz.

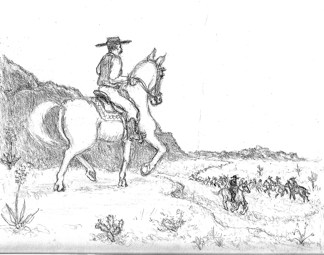

A decade passed in the blink of an eye, during which Weiser led dozens of prospectors to follow him with deadly results. In his eyes, these men were thieves who deserved to die. He had no qualms as he maliciously misled them away from the beautiful Bradshaw Mountains and into the labyrinthine hellhole of the wretched Superstition Mountains wilderness. When these would-be thieves were weakened by heat, thirst, and exhaustion, he whacked them with his trusty shovel, took their food and water, and left their bodies for the buzzards. And only then did he circle back to his real mine in the heavenly cool Bradshaws.

One warm night, as he tossed restlessly in his bed, Weiser thought he heard Waltz’s voice. Opening his eyes, he saw the shadow of a man Waltz’s height at the foot of his bed.

“Who are you?” Weiser whispered.

The specter swayed silently and breathed a sigh of unbearable suffering.

“Could this be Waltz?” he asked himself, then quickly declared, “No, that’s impossible. I don’t believe in ghosts!” Nonetheless, Weiser repeated, “Who are you? Why don’t you answer me,” as he surreptitiously picked up a stout stick he kept beside his bed.

Just then a gust of wind blew in through his open window, sending a sudden and powerful feeling of fear through Weiser’s body.

As the curtains fluttered, the specter seemed to sway.

Weiser inched forward.

But as the breeze abated, the ghostly figure stopped swaying.

Weiser began to relax, and slipped back into sleep, until another gust of wind swept in and tickled his damp skin.

The only thing that moved was his eyes, as Weiser stared at the shadowy figure just beyond the foot of his bed.

And one final gust of wind made him take a firm hold of his stick, rise to his knees, and strike viciously.

His momentum carried him over the foot of his bed and he landed in a heap on the floor.

Spent by his effort, Weiser passed into a stupor and lay there until his rooster crowed and brought him back to reality.

Getting up from the floor, he saw the pile of his clothing in a heap beside him. With bravery born of daylight, he looked at the pile of clothing and said to himself, “This is ridiculous. I’m getting so’s I’m scared of my own shadow.” He stood up straighter and continued, “I’ve got to get out more, maybe get back to playing poker.” He grinned, picturing himself raking in the chips. After all, a man can never have too much money.

Humming to himself, Weiser made himself a pot of coffee and sat down to read the latest issue of the San Francisco Chronicle, which he subscribed to through Walt Johnson’s General Store.

The year after Weiser bought his farm, Julia Thomas and her husband Emil arrived in Phoenix. Julia’s grandmother had come to New Orleans on a slave ship, chained to nine other black girls, and had been sold to a lecherous plantation owner who made her pregnant with Julia’s mother and, fifteen years later, repeated his acts with Julia’s mother to beget Julia herself.

Emil Thomas had won Julia in a poker game in a backstreet saloon. She was a beautiful mulatto woman, adept at pleasing men, but had never felt pleasure for herself until Charlie Smith came to town and swept her off her feet. Poor Julia was devastated when Charlie moved on and forgot her before he got to Tucson.

Like Charlie, Emil had a roving eye. He bought a bakery in the center of Phoenix and put Julia to work baking and selling pastries while he flirted with their female customers. Julia’s hard work made Emil’s bakery the busiest in Phoenix, and he had no trouble borrowing more money.

But this money was not for the bakery. It was for dumping Julia and leaving her with a drawerful of overdue bank loans.

The morning after Emil ran off with a white woman, Julia sat alone at a small table in her bakery, trying to get hold of her new situation. She’d gotten as far as figuring out that what she needed was a good man with deep pockets when Weiser walked in the door.

“I’ve brought you fresh eggs,” Weiser began, then paused and looked more closely at Julia. In her snug bodice and flowing skirts, she was the picture of feminine frailty.

Julia knew most men were suckers for women’s tears, and gently dabbed at her moist eyes with a lace hanky. Looking at her voluptuous body, Weiser felt his groin tingle. He wanted to take her in his arms to console her — and maybe more, if he played his cards right.

Weiser put his eggs on another table and turned back to Julia. “What’s the matter, Mrs. Thomas?” he asked softly.

“Emil’s gone off with one of the dancing girls from Matt’s Saloon,” Julia sobbed, daintily wiping her tears with a lace hanky before looking up at Waltz. “An’ he ain’t coming back. How will I ever manage all by myself?”

Weiser knelt down on one knee beside her chair and eased his arm around her gently shaking shoulders. As he hoped, Julia responded by snuggling closer. Weiser moved his hand to the coils of her curly black hair and rubbed the back of her neck gently as he whispered, “Emil will come back.”

“No,” Julia replied, her soft lips trembling, “he won’t. He took all our money. He ain’t coming back.”

As Julia sobbed softly in his arms, Weiser looked around the tidy little bakery, thinking it was a nice little business that he could use a piece of — diversify his assets, so to speak, while enjoying the dividends of this woman’s gratitude. “Maybe I can help you,” he said, moving his hand from her neck and gently raising her chin until her soft brown eyes met his cool grey ones.

Julia had heard rumors of this Dutchman’s gold. Were they true? “Perhaps they were,” she thought. It couldn’t hurt to try and find out. This man wasn’t young, but she’d noticed the burgeoning bulge in his trousers and knew what to do with it. Rising and taking Weiser’s hand, she put a “closed” sign in the bakery window and led him upstairs to her bed.

The next day, Weiser returned with a baking powder can filled with gold nuggets. With a courtly bow, he handed it to her and said, “This should help you get back on your feet, my dear.”

Julia smiled and put her “closed” sign in the window again. “Thank you,” she said, looking up at him through thick black eyelashes. “I don’t know what I would have done if you hadn’t come along.” Her full lips curved upward. “Do you have time to come upstairs?”

Weiser replied by sliding the bolt shut on the bakery door and covering her lips with his.

Julia bought a horse with some of Weiser’s gold. She ordered a small buggy, too, but Weiser frowned disapprovingly when she mentioned it. Not wanting him to think she was frivolous, Julia cancelled the order.

Of course, she knew Weiser had intended his gold to be a loan, but that could change. And she certainly wasn’t about to bring up the subject. If Weiser started hinting, Julia changed the direction of the conversation by taking his hand and leading him upstairs.

Moreover, on Sundays she filled picnic baskets with mouthwatering fried chicken, and they spent the afternoon in a secluded grove of cottonwood trees down by the river.

The day came when she began to gently question him about his gold. To satisfy her curiosity, Weiser spun a yarn that captured her fascinated attention as he began, “I used to have a partner, Jake Weiser, who came with me from Germany. We were dirt poor but we believed we could get rich in America.”

Julia’s dark eyes filled with admiration as she looked up at Weiser and said, “You were awfully brave to do that, Jacob.”

Weiser smiled modestly and said, “We weren’t thinking about being brave, we just did what we had to, chasing after one gold strike after another. Eventually, we ended up in Mexico, at a Cantina where a poker game was in progress.”

“How exciting,” Julia murmured.

“Not at first, but it became so,” Weiser said, looking down at Julia, who was hanging on his every word. “Even though I didn’t know much about poker, I could see there was some cheating going on. My partner, who wasn’t very brave, saw it too and whispered we should get out of there. But I wanted to stay and see what happened.” He paused for a sip of lemonade.

“Don’t stop,” Julia said breathlessly.

“As it turned out,” Weiser continued, “we couldn’t of left if we wanted to because right then one of the poker players jumped to his feet and accused the dealer of cheating.”

“Oh, my God!” Julia exclaimed.

“And before anyone else could move, the dealer whipped out a pistol from under the table and shot his accuser.”

“No.” Julia put her hand to her mouth.

Weiser reached over and patted her shoulder reassuringly, “But the man wasn’t dead.”

Julia had been holding her breath. She let it out with a soft, “Phew.”

Weiser smiled at her womanly soft heart, and continued. “In the resulting confusion, the crooked dealer jumped on a horse and rode away, chased by the men he had tried to cheat, while Waltz and I stayed with the wounded man and took care of him.”

“How kind you are,” Julia said.

“But that’s not the end of the story,” Weiser said. “Our wounded man was Don Miguel Peralta, who owned land in Mexico and California and Arizona. Don Miguel was so grateful for our help, he rewarded us with a gold mine in the Superstition Mountains.”

“And that’s where you go to get your gold?” Julia whispered.

“It is,” Weiser whispered back, reaching out and putting his hand on her breast, “but you mustn’t tell a soul, my dear. Cross your lovely little heart.”

“I promise,” Julia sighed, lying back on the grassy riverbank and pulling him down beside her.

That evening, after Julia went home, Weiser sat in the rocking chair in front of his house, contemplating the ash of his Cuban cigar. A splendid reddish yellow moon rose on his left and cast its light on his small vegetable patch, but he was too absorbed in his uncertainty about Julia to notice the moon’s beauty.

Before Julia’d come into his life, Weiser’s experiences with women had been one-night stands, and love was just a four letter word. Moreover, in his pre-Julia world, everyone was out for something — usually money — and no one but a fool would help another human being simply out of the so-called goodness of his heart.

“So what was she after?” Weiser asked himself.

The reply came automatically: “She’s after my gold.”

But what was she willing to do to get it? So far, her demands — requests, actually — had been modest. And the sex she gave in return was like nothing he’d experienced before. He certainly didn’t want to give that up!

Well, he didn’t have to do anything about Julia right away, but he did need to replenish his funds. He looked up at the sky, saw only a few scattered clouds, and decided to go back to his mine the next day.

He was followed by a pair of prospectors who had come down from Utah with high hopes of following the Dutchman to his elusive but increasingly famous mine. In what was now an established practice for him, Weiser dispatched these would-be thieves as soon as they reached the Superstition Mountains before proceeding to the haven of his Bradshaw Mountains mine.

Unknown to Weiser, his temporary absence, as brief as it was, left Julia open to the charms of Charlie Smith, the traveling salesman who had swept her off her feet on his earlier visit to Phoenix and then abandoned her. Charlie was down in Tucson, sipping a beer after a hard afternoon with the wife of a customer, when a buddy of his came in and sparked his interest in his old flame. Plunking his briefcase on the bar, the newcomer ordered a beer for himself, then turned to Charlie and said, “Ain’t you the fella who was bangin’ the Thomas woman who owns a bakery up in Phoenix?”

“That’s ancient history,” Charlie replied.

“Well, you might think about adding a new chapter,” the first salesman said with a lascivious leer.

Charlie tilted his chair and ran his hand through his dark curly hair. “Why would I want to do that?” he asked.

“Well, buddy, I hear she’s sharing her buns with the Dutchman,” the first salesman chuckled. “Seems he gave her enough gold to pay off her mortgage. An’ on top of that, folks up there seem to think she knows where his fortune is!”

The next day Charlie was back in Phoenix, renting a room above Matt’s Saloon and seeing Julia on the sly. With the Dutchman out of her bedroom for a few nights, it left an opening that Charlie knew how to fill. And it wasn’t long before he got her thinking about her future. “How long are you gonna fool around with that geezer?” he whispered as he fondled her breasts. “As long as it takes to get his gold?”

“It ain’t like that, Charlie,” Julia protested. “It ain’t just the money. I know I can count on him to take care of me. And you ain’t making any offers, are you?”

Charlie roared with laughter.

Julia pushed Charlie aside and sat up. “I ain’t kidding, Charlie,” she said. “His money is only part of the deal. That old man’s treats me like I was a lady that’s worth protecting, which is more than I can say about you!”

“Whoa there, Ma’am,” Charlie said, reaching up and gently touching Julia’s elbow. “I may not have his money, but I have something else I know you need.” When she didn’t pull away, he continued, “What I was thinking is there might be a way you could have both the old man’s money and me in your bed.”

After a moment, Julia grinned and pulled Charlie to her. And as she lay in his arms, she couldn’t help imagine herself and Charlie at the fancy new hotel over at Coronado, hobnobbing with the rich and famous. No more getting up at dawn to make bread and strudel, she thought as Charlie kissed her eyelids and softly stroked her loins. Raising his head for a moment, Charlie saw her expression and knew he’d hit the jackpot this time.

The day after Weiser returned from his mine, he settled into his usual seat at the poker table in the saloon for a hand, and noticed a couple of men at the bar look his way and snicker. He half rose to go ask them what the joke was, but decided to let it go until he finished the hand he was playing. But they obviously knew something he didn’t.

Later that afternoon, as Weiser was upstairs at the bakery waiting for Julia’s customers to pay for their strudel and go home, he found one of Charlie’s shirts stuffed into a drawer in her bedroom. He left it there and told himself it must be one her husband had left behind, but he couldn’t help but suspect there was something fishy about keeping clothing that belonged to a man who’d been gone for over a year. He wanted desperately to believe Julia was innocent, but images of her in the arms of another man began to insinuate themselves into his imagination.

But even his imagination couldn’t do justice to the actual goings on. Julia was not only falling head over heels for Charlie, she was quickly losing most if not all of her interest in Weiser. If there was any glimmer of light left in her love for him, it was colored gold.

Nonetheless, a couple of months later, as Weiser was feeling more and more neglected by Julia, she suddenly shocked him with what seemed like an act of extraordinary kindness and courage.

After a dry summer, unusually heavy rains melted snow at the Salt River’s source in the mountains and sent floodwater rushing toward Phoenix, further threatening Weiser’s utopia. Concerned for the welfare of his chickens, he decided to leave the comfort of Julia’s bakery and go check on them. “Julia won’t mind if I borrow her horse,” he thought, as he laced up his leather work boots, buttoned up his warm woolen jacket, pulled his wide-brimmed hat down over his ears, and sloshed across the street to the livery stable. John Lutgerdner, who owned the stable, told Weiser he was out of his mind to go to his farm in this weather, what with the river about to overflow its banks. “Them chickens can fend for themselves,” Lutgerdner told Weiser.

“I wouldn’t count on it,” Weiser replied. “Them chickens ain’t smart enough to come in from the rain by themselves.”

Sure enough, Weiser found his silly chickens huddled under a tree as the floodwater crept toward them. He looked around and the only high place he could think of to put them was his roof. Propping a ladder against his house, he began picking the chickens up one by one and carrying them up the ladder.

He hadn’t got far when he had a better idea. “These hens’ll cooperate a darn sight quicker if I put my rooster on the chimney,” he said to himself. But even with the rooster up there, cock-a-doodle-doing his little heart out, it was a good couple of hours before the birds were all safely off the rapidly disappearing ground.

And Julia’s horse was gone. In his concern for the chickens, Weiser had forgotten to tie his horse to the hitching post beside his house.

Seeking dry clothing, Weiser went into his house, but the damp sweater he’d carelessly thrown on his bed the last time he was here wasn’t much improvement over what he already had on. Exhausted from his efforts to save the chickens, and losing the body heat he’d generated climbing up and down the ladder, Weiser huddled on his bed and dozed off.

He was awakened by the moaning of the wind. Or was it something else? He began to hear words, and the moans became the voice of his dead partner. “You can’t get away with it.”

In spite of himself, Weiser shrank back and whispered, “I only did what I had to. Ain’t nothing wrong with taking my share of the gold.”

The ghostly visitor moved his head slowly from side to side and sighed. It sounded unsettlingly like, “Murderr, murderrr...,” as it faded away.

Overcome by his situation, Weiser sank back on his pillow, closed his eyes, and sobbed.

Ten minutes later, he opened his eyes and saw a feeble ray of late afternoon light on the foot of his bed. “At least it’s stopped raining,” he thought. Looking down, his optimism faded as he saw the water in his house had not gone down. On the bright side, if there was one, neither had it risen, as far as he could tell.

The sun disappeared and the rain resumed. Weiser sat up, put one foot on the floor, and it splashed. He put his head in his hands, closed his eyes, and tried to summon the comforting image of Julia. She’ll find me, he told himself, but doubt nibbled at his confidence, asking, “Will she figure out where I am? And will she care?”

Meanwhile, Julia’s horse had returned to the livery stable without Weiser. Concerned that his original prediction for disaster was correct, John Lutgerdner, the blacksmith, hurried to Julia’s bakery. “I told him he was crazy to go out there, what with the river rising,” Lutgerdner said. “But I wouldn’t want him to catch his death of cold on account of helping his chickens.” He paused, then said, “If you like, Missus Thomas, I’ll help you look for him.”

Julia’s last customers had gone home an hour ago. She pulled on her waterproof mackintosh, locked the door to the bakery, and followed Lutgerdner back to the stable. In a matter of minutes, he had a horse hitched to his buggy and they were on their way.

The rain, which had let up for a few minutes, began again in earnest. Water flowed across a low place in the road, causing the horse to hesitate. Lutgerdner handed his reins to Julia and climbed out of the buggy. Putting his hand on his horse’s bridle, he spoke gently to the nervous beast and led him through the water to higher ground beyond the puddle.

While his rescuers struggled to reach Weiser, steady rain made the afternoon darker. Weiser drifted in and out of sleep, afraid his ghostly visitor might return.

Having safely gotten past the deepest of the puddles, Julia and Lutgerdner reached Weiser’s farm, but saw no light in his window. Was this miserable trip all for nothing? But where else could the man be? Unbidden, the image of him being helplessly washed downriver passed through Julia’s mind. Maybe she cared for him more than she’d imagined.

“Come on,” she said to Lutgerdner, “he must be inside the house.”

Now it was Lutgerdner who hesitated. “I think the house is starting to melt,” he said nervously.

“All the more reason to hurry,” Julia replied, jumping down from the buggy and landing in mud up to the ankles of her high-button shoes.

Lutgerdner lent her a hand and they waded to Weiser’s door. It was unlocked, but swollen shut.

Huddled on his bed and shaking with cold, Weiser thought he heard Julia call, “Jacob, are you in there?” Afraid he was hearing things, but hoping she was real, he tried to reply. All that came from his mouth was a whisper.

Nonetheless, Julia heard him. “He’s in there!” she cried out.

Just then, a corner of the roof made a harsh, high-pitched sound as it settled slightly, signaling impending collapse.

Lutgerdner was a big, strong man accustomed to lifting heavy loads. “Come on,” Julia urged him, “put your shoulder to it. We’ve got to get him out.”

Lutgerdner backed off a little, then really leaned into it. The door didn’t budge. He tried again. Still no shift. But it finally yielded, albeit just a fraction of an inch, on his third attempt, and a moment later they were inside.

The roof creaked again, louder this time. There was no time for conversation, as Lutgerdner picked Weiser up and carried him to the buggy and placed him on the seat. As he did so, the tortured adobe sighed and collapsed into a heap of mud, with only a chimney rising to indicate this had once been a man’s home.

Julia and Lutgerdner started home with Weiser propped between them. Weiser was shaking uncontrollably, his usually tanned face was deathly pale, and his lips and ears were turning blue. “What if he dies?” Julia thought. “What will I do if he dies?” She’d been counting on his gold to secure her future. “He can’t die now,” she thought. She turned to Lutgerdner, urging him to go faster.

“Can’t do it, Ma’am,” Lutgerdner replied. He turned his head to look at her briefly and continued, “I’m doing the best I can. We’ll be lucky to get home without having to make a detour.”

As it turned out, they were able to make it across the low spot and reach Julia’s bakery without further incident. Without having to be asked, Lutgerdner carried Weiser inside. And he helped Julia set up a cot for Weiser in her storeroom, strip Weiser of his saturated clothing, and help him into his temporary bed.

The following morning Weiser was worse. His breath was short, and he had a wracking cough that produced slimy, green mucus. Julia felt his forehead with her wrist and it was abnormally hot. Fearing pneumonia, she put on her mackintosh and ran next door to ask her neighbor’s boy Tom to fetch Doc Swanson.

Doc Swanson didn’t consider Weiser’s symptoms serious enough for a house call until the following day, but he did give Tom a prescription for salicylic acid to ease Weiser’s “discomfort.”

But Weiser’s condition really was pneumonia. It would take the next three months of chicken soup and constant care for him to even begin to recover.

Between bouts of coughing wracking his body, Weiser had plenty of time to think about his future. “There’s no denying that I owe Julia my life,” he told himself many times. “And she certainly is attentive, feeding me hot broth when I’m too feeble to lift a spoon. Would she do that if she doesn’t have feelings for me?”

But just as Weiser began to believe he could trust Julia, she began neglecting him, frequently failing to appear promptly to his summons.

Julia’s increasing slowness to respond was partly because she found it hard to hide her increasing aversion to Weiser’s wreck of a body, which bore little resemblance to the virile man he’d been before the flood. To make matters worse, he began to stink. Sometimes just being in the same room with Weiser would make her gag.

What’s more, when she did show up, Julia’s dress would be rumpled, her face flushed, and the demure coil of thick black curls on the crown of her head a tousled mess.

And to top it off, Weiser could hear the low tones of a man’s voice long after the bakery should have been empty of customers.

Seeing her aversion and suspecting her disloyalty, Weiser cast desperately for a way to regain her affection. “Perhaps I can get her to love me again,” he thought, “if I promise her a share of the gold nuggets buried beneath my hearth. An’ if that ain’t enough, I can promise to throw in a map to my mine. Only the map will have to be a sham. I can’t take a chance on anyone finding my real mine and Waltz’s body.”

The next morning, as Julia was fluffing his pillow, Weiser put his hand on her arm. Resisting the urge to pull away, Julia forced a smile to her lips and said, “It’s good to see you’re feeling better.”

Weiser tried to smile in return but, regrettably, the result was an ugly, twisted expression more like a grimace of pain.

Julia eased her arm from his grip and turned to go.

Desperate for her company, Weiser half-sat up and said, “Don’t go, my dear. There’s something I want to talk to you about.”

The only thing remotely interesting about Weiser now was his gold. On the off chance this was what he was thinking about, Julia paused and looked back at him.

Encouraged, Weiser plunged ahead, “I have a box of gold out at my farm. It’s buried under my hearth.” Intoxicated by her attention, he blurted out, “I’ll give you half that gold if you’ll help me get it.”

Her interest in the old man reignited, Julia bent and gently adjusted Weiser’s pillow. “What are you talking about?” she said. “There ain’t any hearth left, mister. Your house is just a pile of mud and rubble.”

“I know that,” Weiser said peevishly, “but the chimney is still there, ain’t it?”

Julia thought a minute and remembered the chimney sticking out of the mud pile that had been his home. “Maybe it is,” she admitted.

“Well if it is, we can find my hearth, an’ that’s where the gold’s buried!” Weiser exclaimed in an “aha” tone of voice.

Julia’s eyes sparkled at the prospect of this treasure, but she also realized it wouldn’t be an easy task to retrieve it. “Slow down, Jacob,” she said quickly. “Even if we do find it, we’re going to need more help than I can give you.” She knew she could never suggest Charlie, because it would enrage Weiser’s jealousy and suspicions.

“How about that fella across the street, the one with the livery stable?” Weiser suggested. “The fella who came with you when my house melted. He seems like a man who can keep his mouth shut. An’ anyways, he don’t need to know what’s in the box.”

The prospect of going after his gold was the best tonic Weiser could have taken. Within a week, he was out of bed and, with the help of a stout cane, walking as far as Lutgerdner’s stable. “Doc Swanson thought I was a goner,” he told Lutgerdner.

“So did I,” Lutgerdner replied. “But I guess you’re too ornery to die.”

A week later, Julia arranged for Lutgerdner to drive Weiser and her back to Weiser’s farm, disguising the trip as a nostalgic visit for Weiser. They’d barely arrived when the farmer who lived next door showed up, chewing tobacco and hitching up his britches. After peering astutely at Weiser, the farmer turned his head aside and spat a brown stream of tobacco juice before saying, “I took care of them chickens you left behind, mister. Are you wanting to git them back?”

Weiser looked quickly at Julia. How could he have forgotten his precious chickens? A little shaken at what this said about his memory, he played for time, “What do you say, Julia? Do you want to give my chicks a new home?”

The last thing Julia wanted was a flock of chickens pecking around in her yard. But neither did she want to offend Weiser, at least until she had her hands on his gold. “Perhaps in a few weeks,” she temporized, “when you’re able to take care of them.”

Seeing an opportunity to make a few bucks, the farmer said, “I been looking after your chickens an’ feeding them while you was away,” he said. “An’ it don’t look like you’ll be moving’ back anytime soon. You can take your chickens with you or you can sell ’em to me, but either way, you already owe twenty bucks for their feed.”

Weiser’s jaw dropped in amazement, but the farmer’s offer suited Julia. Putting her hand on Weiser’s arm, she leaned closer to him and said softly, “Maybe you should let him have your chickens, Jacob. They’ll be better off out here.”

Weiser reluctantly agreed to let him keep the chickens, and the farmer went home with a smile.

While Weiser and the farmer negotiated, Lutgerdner took his pick, explored the area around the eroding remnant of Weiser’s chimney, and found Weiser’s pine candle box in a matter of minutes. With Weiser’s supervision, Lutgerdner excavated the box, lifted it into the wagon, and drove back to Weiser’s temporary home at Julia’s. As they bounced along, Weiser’s spirits soared at having his gold back in his possession, where he could see it and touch it anytime he wanted. Moreover, it would restore his place in Julia’s bed, or so he thought.

As the bakery door closed behind Lutgerdner, Weiser put his arm around Julia’s shoulders and tried to lead her to the stairs.

But she pulled away, “Not so fast there, mister. Have you forgot your promise to give me half this gold?”

“Of course not,” Weiser said quickly. “But do you need it right this minute?”

“Yes, I do,” Julia replied. “We had a deal. And I sure as hell held up my part of the bargain.”

“Don’t you trust me?” Weiser said, in a tone of righteous indignation stoked by his underlying suspicion that she was as greedy as he was.

“Of course I do,” Julia said. “But I’d trust you better if you would trust me with the gold you already promised me.”

Weiser tried again to lead her upstairs, but she knew better than to give in to his sexual advances in exchange for another unfulfilled promise.

Her delay was enough to push Weiser’s barely controlled jealousy over the edge. Turning away abruptly, he pushed his box of gold under his cot, lay down, and turned his face to the wall.