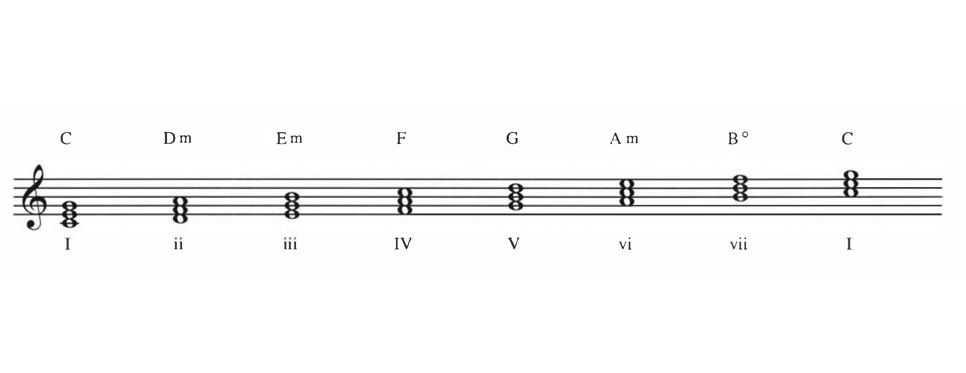

TRIADS ON EVERY NOTE

Play a triad on every note of the major scale, staying in the key

C major is once again our “default” key. Triads built on every note of the scale will involve only white keys. Play each of these chords and listen to the quality of the sound. Some will be major, some will be minor. The triad built on degree VII sounds strange—not major, not minor. It is called “diminished.” The different qualities of these chords come from the intervals that separate the notes.

You already know the difference between a perfect 5th and a diminished 5th (smaller by a half step). There are two kinds of 3rds—major and minor. Obviously, the minor 3rd is smaller than the major 3rd, by a half step. Compare the notes C up to E (count the keys in between them), then C up to E♭. The first interval is a major 3rd; the second interval is a minor 3rd. Play them each again, blocked, then broken. Close your eyes and hear the difference in the sound.

- The numbering and labeling of scale tones always begins on the lowest note and ascends.

- In popular music or jazz music, the symbol for minor is a lowercase “m”. The symbol for diminished is a degree sign, °, or a lower case “d.”

- It is convenient to label with Roman numerals; finger numbers won’t get mixed up with chord numbers.

- If there is no quality symbol, the chord is major.

If you examine the C major triad closely, you will find that the outside 5th—C up to G—is perfect. The interval of a 3rd—from C up to E—is a major one (count the keys between the two notes). From E up to G is a minor 3rd (count the keys between the two notes).

Now you know what a major triad consists of. Find other major triads and test out these qualities.

Now play once again the triads built on each note of the C major scale. Listen for the major triads, the minor triads, and that strange-sounding triad built on B—the diminished triad. It is made of two minor 3rds. The outside 5th is diminished.

- As you play every chord in the scale, you discover that there are only three major chords.

- All the other chords are minor, except VII, which is diminished.

Track 63

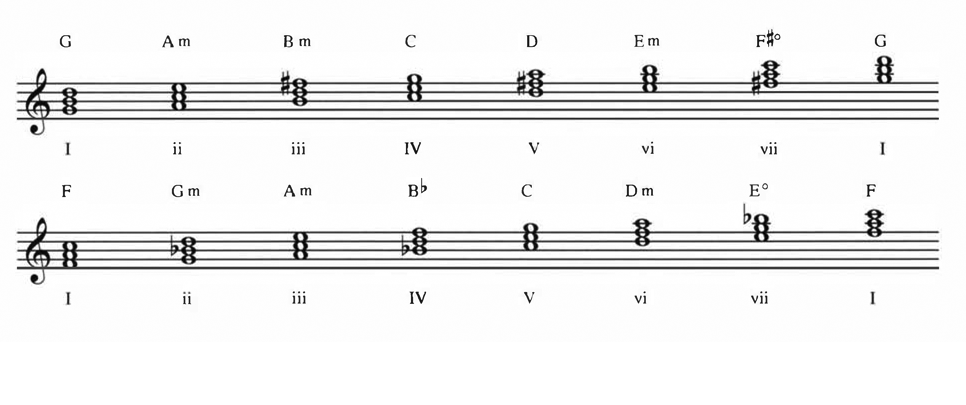

OTHER KEYS, OTHER TRIADS

Get to know the keys by building chords on every note of the scale

For some in-depth practice of a key, build chords on every note of the scale, but stay in the key. In other words, when playing chords in the key of G major, any chord with an F has to use the note F♯. Be sure to give the other hand the same opportunity!

You will also find that the quality of each chord is the same as the corresponding triad in C major.

This is great practice for getting to know your keys! Play in the keys of one and two sharps and flats, triads on each key. You have to think hard, but get accustomed to the “language” of each new key.

You can now start labeling the chords with Roman numerals: I, II, III, IV, V, VI, VII, I. Circle the chords that sound like major. They should be the same in each key. Put small “m’s” under the minor chords, a small “d” under the diminished chord.

- Play these chords in each hand.

- Label the chords, under the chords with Roman numerals and/or above the chords with letter names, “pop” style.

This theory of chords (harmony), with the bass or “root” tones relating to each other in a musical way, was penned by Jean-Philippe Rameau in 1722. We are still using this harmonic organization! There are other digressions and other theories composers use, but for all of us, this basic harmonic theory is important and useful.

Jazz and popular musicians usually label their chords with the letter name of the chord. If there are alterations, or additions to the chord, those are indicated in the chord symbols above the melody, or in some cases over the measure where they occur. A melody is not always needed.

Track 64

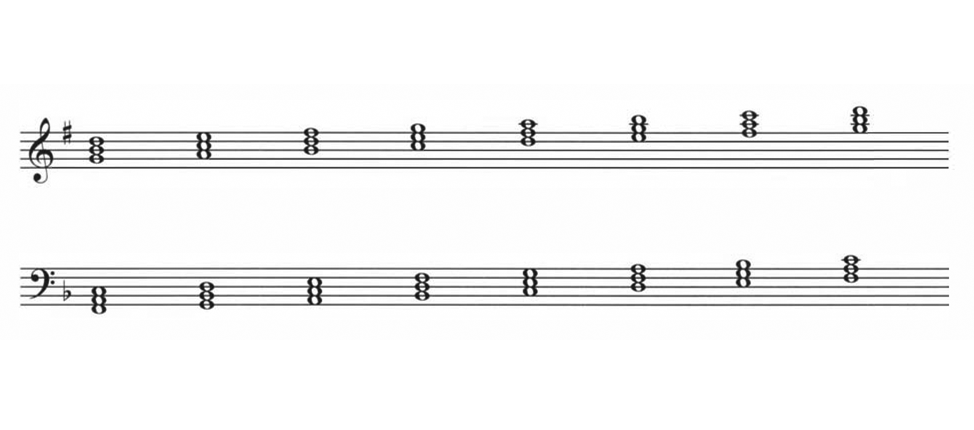

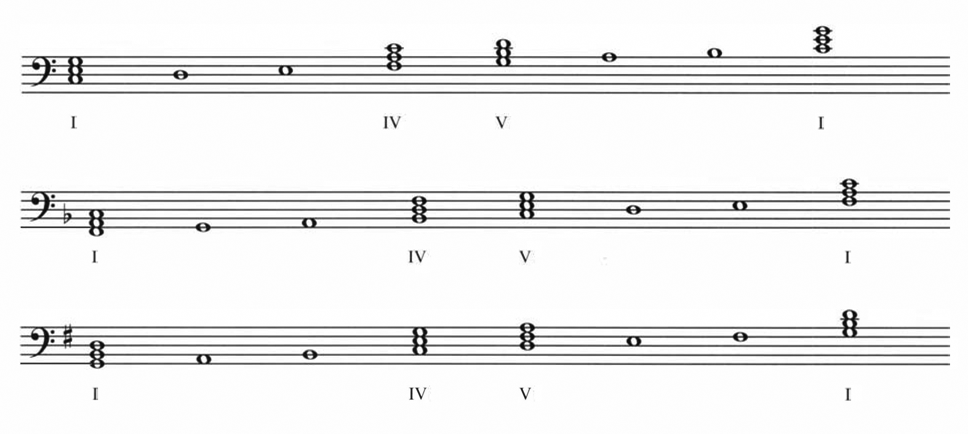

PRIMARY CHORDS

In building chords on every scale note, you will discover only three major ones

As you play chords on every note of the C major scale, listen for the quality of each chord. Choose the three major chords—C, F, and G major—and play them several times. These are the “primary chords.” Play them broken, then blocked. You are getting used to moving from chord to chord.

Test the interval structure of each chord: Is the 5th perfect? Is the major 3rd the lower interval, minor 3rd the upper interval?

Left Hand on C Major Chord

- The arm is parallel to the floor.

- The palm of the hand has a nice “dome?”

- Thumb is on its side and slanted toward the wrist.

- The fifth finger is tall, not collapsed.

You can accompany just about any tune with these three chords, and sometimes you only need I and V, or just I.

The list of three-chord songs is endless! Typical are the tunes “Oh, When the Saints,” “This Land is Your Land,” “Michael Row the Boat Ashore,” and “Yellow Submarine.”

Left Hand on F Major Chord

- The hand looks the same as it did on the C major chord.

- Since the pressed keys are all white, the fingers are slightly away from the black keys.

Usually at the end of these tunes the chord progression V to I is used. This is the sound that gives such finality to a piece. It is called a “cadence.” Often the interval of a 7th is added to the penultimate chord to make that chord more dissonant and to make the progression toward the end more active. Play, in the key of C major, the V or G chord and add one more third on the top. This will read G-B-D-F; the interval from the root note, G, to the top note, F, is a 7th. Play this seventh chord, labeled V7 or G7, with two hands (two notes in each hand). Then play the I or C chord. Listen to some Beethoven symphonies and overtures. Beethoven often used the V to I cadence for dramatic effect. At the end of the Fifth Symphony he repeats the progression V to I many times. You can play the keys G to C along with the recording. Can you tell if he uses the seventh of the G chord?

Left Hand on G Major Chord

- The hand looks the same, in a strong, controlled, relaxed position.

- Practice moving between these three chords: C, F, to G.

- Change the order: C to G to F to G to C. Play these blocked, then broken.

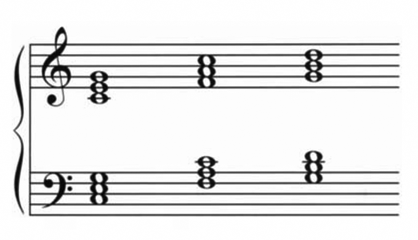

- Here are the primary chords written on the staff, in both the treble and the bass.

- Play the chords adding a C chord at the end.

- Count evenly, 2 or 3 beats per chord.

“LA BAMBA”

A familiar tune, with only primary chords for accompaniment

“La Bamba” is a traditional Latin melody. You need only the three primary chords to accompany the tune. Play the C major chord, to the F major chord, to the G major chord. Hold the G major chord twice as long as the other two. If you do this over and over, you have played accompaniment for the whole song! The melody begins on (up an octave, away from the left hand), and there are not many different notes.

If you play the primary chords in a broken style, left hand fingers 5-3-1, 5-3-1, 5-3-1, you can make a more interesting accompaniment. Try it in the other hand also. (In the right hand the finger numbers will be 1-3-5.)

Make up the simplest tune possible by playing the chords in one hand, and one note of the chord in the other hand. In the key of C major, the very simple melody will be C, F, G. Now try the middle note of each chord in the other hand: the melody will be E, A, B. This very simple way of improvising should give you a boost toward making up your own melody.

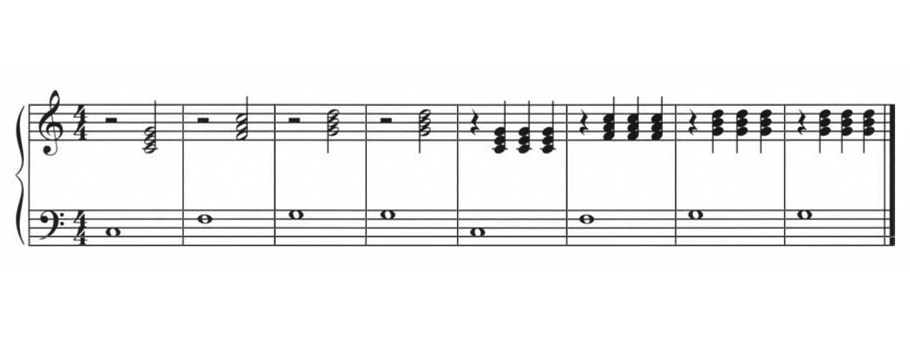

- I have written out the primary chords one note at a time, so you can see how to play them while improvising a simple tune in the right hand.

To make it easier to improvise, hold each left hand chord down for four long beats. This will give you time to play the notes of the chord one at a time in the right hand, and play some notes in between. If you play the C major five-finger pattern, you are playing the triad with passing notes in between.

Primary Chord Exercise

- A simple melody in the key of C major, with accompanying chords in the left hand.

- How did I choose those particular chords?

- How did I choose where to play them?

- Try out chord inversions in left hand.

Track 65

ADD SYNCOPATION

This is beginning to sound almost like “salsa” music!

The word “syncopation” means to move a strong beat over to a weaker beat. This music is more difficult to read, because it takes more notation to write it correctly. As in other rhythmic patterns, you need to feel it first. Listen to Latin-based popular music—it is all syncopated. The main beats are either anticipated or delayed. Jazz and rock and roll music are also performed this way. Listen to a popular song, then look at the music for it. It usually looks very complicated, unless you have the simplest arrangement.

A good example of this is “Linus and Lucy” from the Peanuts cartoons. If you try to play the melody by ear, you will find that the first section consists of only three notes, whole steps apart. But look at the printed music and listen to a recording. The syncopations sound normal and easy to play; but a glance at the music tells you it is not as easy as you thought, at least hands together.

- Another way to accompany a simple tune like “La Bamba” is to play the bass note, or name-of-the-chord note, in the left hand, the chord in the right hand.

- You want to make it fit into four measures of 4/4 time.

“The Girl from Ipanema” is another example of a melody (a little more complicated) over a syncopated accompaniment. This is a bossa nova beat, and you can study it in any Latin-based music book, or by looking at the music and analyzing it. But I warn you, it is complicated unless you feel it first.

We can make our simple I, IV, V accompaniment more interesting, however, by just changing the rhythm a tiny bit. Play the broken chords in a pattern of half note followed by two quarter notes: 1-2, 3,4; 1-2, 3,4. When you play the G major chord, play two quarter notes and hold the third note for six beats. Lonnng, short, short; Lonnng, short, short; short, short, Loooonnng. This whole pattern fills the time of four measures of 4/4 time.

- This is a slightly syncopated version of the accompaniment figure.

Track 66

SIMPLE TUNES TO ACCOMPANY

Fewer words and more music!

I can use folk tunes and eighteenth- and nineteenth-century pieces in this book, but for more recent popular and classical pieces you must go to a music store, or to an online music store. There are usually three levels of arrangements: beginner, intermediate, and advanced. You will need to examine the music to see what you can handle—the beginner or intermediate arrangements.

If you purchase a popular tune because it looks simple enough to play, you may find, when you play it at home, that it sounds a bit “square” and uninteresting. There are two reasons for this: 1. You don’t have a band to back you up; and 2. All the syncopations are deleted so it will be easy to read.

Practice the music until it feels easy and you are comfortable with it. Then play along with a recording, if you have it. This will help you add some rhythmic pizzazz, and will make you feel as if you are part of the band! If you don’t have a recording, play it as you hear it in your head. The main clue here is: You must feel comfortable playing it; it has to be easy.

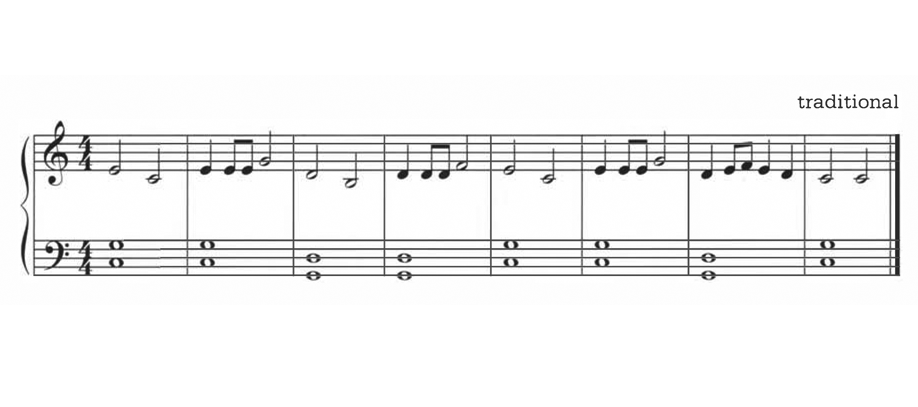

Skip to My Lou

- A simple tune with an accompaniment in the left hand.

Use your ear to try and pick out simple tunes, like “When the Saints,” “This Land Is Your Land,” and “Yellow Submarine.” If you have a favorite tune on your iPod, play along with it to find one or two notes that fit the tune Keep trying!

When you have a tune you can play (or whistle), make up a simple two- or three-chord accompaniment in the left hand. You can use blocked chords or 5ths and 6ths. You can break up the chords and fit the accompaniment to the melody.

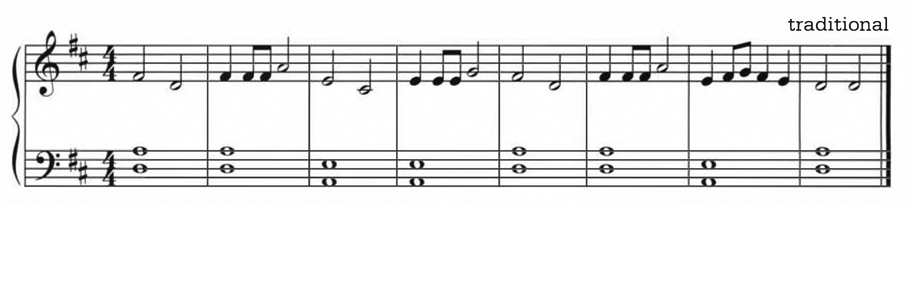

Skip to My Lou

- The same tune transposed to D major.

Track 67