CHAPTER 16

Freedom Day

MY AUNT STANDS IN the grass outside the small house and waves as I back the car up the track. I am sorry to be saying good-bye to her. As with all my mother’s siblings, I am immensely touched by her willingness to talk to me. After my mother left South Africa, said Doreen, she was lonely for her sister and would sometimes look up her name in the Johannesburg phone book. It was listed for a long time afterward, and Doreen would pretend to herself that my mother still lived there. Then, one day, it was gone.

I am driving five hours north, over a mountain pass usable only in summer, down into the Karoo and a small town called Willowmore. It once took sixteen hours to get here from the coast, but it takes me five, through a semidesert landscape of bewildering emptiness.

It was here in 1820, three years after the Voortrekkers passed through, that a man called William Joseph Moore built a farm. It is also where, as my mother had it, the good genes were from. For decades, her mother’s family, the Doubells, lived in Willowmore and made a living mending fences on the ostrich farms, until they moved to the coast in search of an easier life.

In his history of the town, Norrie Steyn makes the place sound idyllic, a settlement “beside a murmuring stream, winding its way through a bush-covered, game-infested basin, flanked by low hills and lying at the foot of a mountain above which vultures hovered.” There is a certain arid beauty to it, and I stop to take photos of the deserted road cleaving through scrubland to the horizon and beyond. Ostriches are still farmed here, and the farms are so large—or there are so few ostriches—that fifty miles can pass and you will see only a couple of birds at the fence, tail feathers hanging like mud flaps, heads poking over the wire with that look they all have, half daffy, half lethal. “Welkom,” reads a sign at the turnoff from the highway. It wouldn’t take much, I think, for the Karoo to reclaim this town.

The high street is empty. There is an old Methodist church with a corrugated tin roof and a coffee shop with “1906” inscribed over the door. The only sign of life comes from a liquor store at the far end of the main strip. I can hear Elton John’s “Nikita” blasting from somewhere within. When I knock at the door of the guesthouse, a block back from the high street and in a Dutch gabled building in traditional green and white, the man that opens it blinks and looks up the street, as if to see where I have landed my spaceship.

“Have you any vacancies?” I say.

There is a long pause. “You mean, is there anywhere for you to sleep?”

“Yes.”

Another pause. “I wouldn’t turn a pretty girl away. Follow me.”

We walk down a dim corridor, decorated with framed photos and oil lamps and oppressively silent.

“Hot,” spits the man, by way of general introduction, “the Karoo.”

• • •

WHEN I EMERGE from my room a little later, the man comes out from his office and shows me the photos on the wall. I’ve told him I’m here to do the family tree, and as it turns out, many of the photos are of my hatchet-faced relatives. Next to a picture of Queen Victoria and a sign that reads “Blessed Are the Meek” is a framed sepia shot from the turn of the century of town dignitaries. A man in the middle, square-shouldered, with a brushed mustache and a cigar in his hand, holding a homburg, is identified as an Oosthuizen. The man sitting next to him is a General Louis Botha. Next to that is a photo of the United Cricket Club of Willowmore, 1919–1920, with, surprisingly, a mixture of black and white players.

He asks what names I’m looking for.

“Doubell,” I say.

“Yes. There were Doubells.”

“And Oost—” I can’t pronounce it. “Oosthuizen.”

He takes this calmly. “West-hazen. There.”

From the lounge comes the sound of a voice I recognize, although it takes a moment to place it: Geoff Boycott. The TV is tuned to a satellite sports channel and is broadcasting an England cricket match.

If I like, says the owner, he’ll call his neighbor Stella and she’ll drive me to the cemetery to meet the Doubells. Why not?

The begraafplase is up the hill. Stella says to watch out for snakes, but for once I’m not worried about the wildlife. To be bitten by a snake and keel over across the marble slab of a dead ancestor would be too contrived an ending, even by my mother’s standards. It is enough that they, of the good genes, mended fences for a living. My grandmother Sarah died six hundred miles east of here in Durban, the photo of her grave offering no clues as to its whereabouts, beyond the gravestone next to it, a black marble monstrosity with the name Connic chiseled onto it. I had asked Gloria, my mother’s cousin and the only possible source of information, if she knew where her aunt was buried, and she had looked distraught and said, “I never thought to ask my mother.” But it is definitely not in Willowmore.

Stella likes coming up here, she says. It’s peaceful among the headstones. Looking out over the town to the desert beyond, she tells me they are trying to market Willowmore as a second-home location for rich people living on the coast. The words they are using are “authentic desert living” and “spiritual retreat.” She says this with enough dryness to communicate her thoughts on the matter.

“You don’t mind if I look around for a minute?”

“No,” she says. “I’m fine here.”

Every other grave is a Doubell or a Van Vuuren. The women are Magdalena Magrita or Marguerite Madeline. The men are mostly Johannes. “God is Liefde,” it says on lots of graves, which are bleached white as bone. At the edge of the cemetery, a line of trees filters the last of the day’s sun, sending fingers of shadow across the white stone. “Did you get what you wanted?” says Stella.

I eat at the guesthouse that night, where the meat is dark like duck and chewy like car tires. “You still happy, lady?” says the owner. We’re alone in the dining room. I nod, and he sits down to join me. He tells me how he once bought an ostrich for 110 rand and sold it for thousands, although, he says, by and large ostriches disappoint. They are temperamental, like the women who used to wear their feathers. They die easily. I ask him about fence-mending. “Draad-maker in Afrikaans. It was a skilled job. As the farms got smaller they needed more fences. You had to get wood from far away, to make the corner pieces. Slate stones to plant in the ground. You had to make them jackal-proof, with three wires along the top. A skill, a real skill. Of course, only the blacks and the coloreds do it now.”

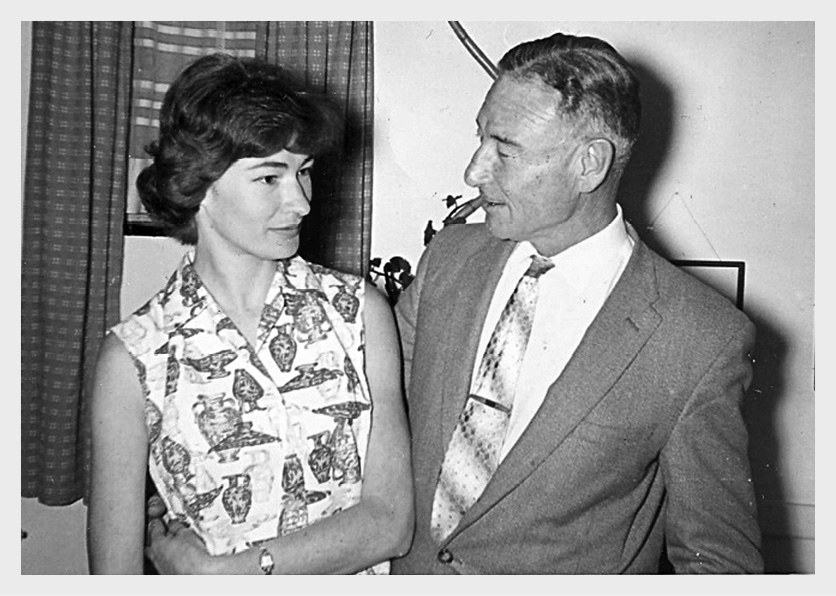

My mother at her mother's grave.

After dinner, the light outside is pale mauve and the temperature has come down to the low eighties. I walk across the street to the only place apart from the liquor store that is open, the Die Gert Greeff old people’s home.

Outside the French windows the residents sit on benches, so old and sand-blasted that even without the shadows you can’t tell what race or sex they are. It is a state-funded home, so I assume they are everything. I find a nurse and ask if I can talk to anyone about the town. She shrugs and says to try Gerty, upstairs. I climb the stairs and walk down a dim corridor. All the doors are open and the rooms mostly empty, except for one, in which a woman is awake and scrunched into a chair by the window. She could be three hundred years old. It takes a moment for us to find a common language, and then she says, in what sounds like a heavy German accent, that her name is Gerty Roux and she was born in the town in 1920, making her some ten years younger than my grandmother. I ask if I can talk to her about the town, and she nods. I mention my grandmother’s name, and she says, yes, there were lots of Doubells.

“They were fence-menders,” I say. Gerty does not reply to this. It is one of those encounters that unfolds in non sequiturs, as in dreams.

“What was it like here then?” I say. It’s not my finest moment in journalism, and to her credit, despite my inept questioning, she manages to dredge up a few details. They worked hard; they got up at five a.m.; they traveled in from the farms once a week to go to the bioscope in town. I can’t think of anything else to say. I sit there with Gerty in silence for what is probably only a few minutes but feels like hours, looking, as she does, out the window. The lace curtain flutters. If you lived here long enough, I think, the day would come when you jumped up from your chair and ran screaming down the high street in your nightgown. Or fell in love with the first person who smelled of the city.

I leave Gerty Roux and go back downstairs. On the way out of the home, I run into a young nurse. She says she is on temporary transfer here from Cape Town. I ask if she misses the city, and she gives me a desperate look. “God, yes.”

The next morning, I get up at 4:00 a.m. The drive to the airport is only two hours, on a regular road with no mountain passes, and my flight isn’t till noon. But I would rather sit in the waiting room for four hours than in this desiccated vacuum.

• • •

FROM WHAT BOTH DOREEN and Tony said, the greater betrayal was not what happened in court, but the fact that their mother took Jimmy back afterward. In fact, Marjorie did divorce Jimmy, two years after the court case collapsed. My mother never mentioned this, and nor did anyone else. It must have seemed a hopeless gesture, too little, too late, and then he died anyway. But I am curious to discover she took a stand at all, something I find out about only by chance. When I get back to Johannesburg, I go online for one last trawl through the National Archives’ database, and there it is. I don’t know how I missed it the first time: Marjorie Violet divorced from James Mauritz, with a shelf and reference number.

I hesitate to go back to Pretoria. The divorce is probably summarized in a single line, and what’s the point of driving fifty miles for that? In the end, I go less out of curiosity than as a kind of marker for how far I’ve come. I drive myself this time, park in the car park, and, entering the reading room, feel none of the terror of the first visit. I am so pleased with myself about this that when my phone rings as I’m putting my bag in the locker, I answer cheerfully. I must be less resolved than I think. It’s my friend Sam, calling from the office in London. “Do you want anything from the trolley?” he says, very pleased with his joke—it is teatime at home—and it’s all I can do not to burst into tears. “I’ll have a peppermint tea,” I say weakly, and hang up the phone.

It turns out the divorce record is more than a line long. The restitution order was served on Jimmy personally by a Deputy Sheriff Lotz at no. 46 single quarters, West Rand Consolidated Mines, in Krugersdorp. He was ordered to pay £10 a month to Marjorie, plus £30 maintenance for the five children still living at home. When he didn’t turn up for the hearing, the judge granted the divorce by default. The court charged Marjorie £1.50 for serving him with papers. To secure a quick settlement, the grounds on which she divorced him were, with cosmic-sized irony, “malicious desertion.” All their lives they had tried to get rid of this man, and now his absence—in the language of the court, his failure to observe “conjugal rights”—was the only legal way to dispense with him.

Looking at those divorce papers, I feel sympathy for Marjorie, the woman about whom no one has much to say—except for Steven, protecting his mother a little, who told me she had once wanted to be a Catholic missionary. She was of Scottish origin. She got pregnant not long after meeting Jimmy. Afterward, she would say she had always been afraid of her husband, thought him “a devil” right from the off, and was reluctant to marry, but her parents had pressured her into it. And yet, said her youngest son, there came a moment when he realized that “at some level, she must have loved the old bugger. And I thought, ‘I’ll be damned.’”

Apart from the telegram she sent my mother telling her of her father’s death, the only example I have of Marjorie’s voice is a note she wrote to my mother on the back of a photo she sent to England shortly after she’d moved. “Dearest Pauline,” she writes, “I wrote to you last week and very stupidly lost the letter. This is just to say thanks to you. We are very grateful and the money was useful. Bless you! Anyway, you can be sure of getting it back soon but that doesn’t mean that I am not grateful and very touched by what you did.” There follow several paragraphs of family news. Then Marjorie writes: “Hope you like the photo.” The photo is, incredibly, of my mother and her father, taken on the day she left South Africa, his arm around her waist while my mother stares like a statue into the distance. With lots of kisses, she signs off, “love, M.”

As with everything else, accounts of Jimmy’s death varied among the siblings. Tony thought it was my mother who was asked to identify the body, but that can’t have been the case; she was already in England. Doreen said she was walking to church from the children’s home with Fay when Tony pulled up on his motorbike. When he told them their father was dead, “I was so pleased. That’s all I felt. Pleased and relieved.” She said Fay started screaming and had to be calmed down. “I couldn’t stop shaking,” says Fay. “When you’ve been frightened all your life, it’s such a relief.” Steven said his mother was terrified there would be an open coffin at the funeral and she would have to see his face again.

To hell with all that: my mother on the day she left South Africa for England, in November 1960.

• • •

FAY IS HAVING A LITTLE gathering at her house. It is not a reunion per se. Words like “reunion” put too much pressure on attendees, plus the idea of togetherness in this family is so toxic as to be almost funny. “It’d be hilarious,” said my cousin Jason while we were sitting in the garden with his mother on the coast. “We could get all of you in a room together, get in loads of booze, and invite Jerry Springer.”

“You’re not big,” snapped Doreen, “and you’re not clever.”

But Fay is being optimistic. Her brother Tony is coming, whom she hasn’t seen for nineteen years, and Tony’s ex-wife, my aunt Liz, and some of Liz’s boys, plus Fay’s daughter-in-law and her husband, Trevor. She invited her daughter, Victoria, whose reaction I can just imagine. Yes, says Fay, it was along the lines of “I’d rather stick pins in my eyes.”

At her round dining table, my aunt and I excitedly plan how many sandwiches we’ll need. A few days later, we drive to the shopping mall to pick them up. They are dainty white triangles with their crusts taken off—not like the huge, chunky doorsteps my mother used to make—laid out on a large silver tray. Before everyone arrives, I take a photo of the fridge, which has been stripped of food to make way for a pyramid of beer bottles. We drag plastic chairs out onto the terrace. It’s an overcast day, but we are in high spirits.

“Won’t it be weird to see Tony?” I ask.

Fay giggles. “Very weird.”

“Will he and Liz be all right in the same room together?”

“Oh, yes.”

Everything flows off Fay’s back. It is an attitude often mistaken for passivity, but one that I have come to understand as a Zen-like transcendence. I ask her how many years it has been since all the siblings were in a room together. She supposes it was at her mother’s funeral longer than two decades ago, although “Of course, your mom wasn’t there for that.” It is always Fay, the sensible one, who is called upon to break news of a death in the family. It was Fay who rang my mother with news of Mike’s death, and who drove over to her own mother’s house to break the same news. Marjorie had been drinking heavily for a long time by then. She came to the door, says Fay, saw her daughter’s face, and said afterward, “I knew instantly. But I thought it would be Doreen.” Marjorie put a leash on the dog and went out for a long walk. When she came back, Fay says, she said good-bye and left.

Before that, she supposes, the nearest they got to a family reunion was my mother’s first trip back to South Africa, in 1967, before the siblings had fully scattered to pursue their own lives. Steven had told me about this; he remembered the visit well. He remembered one incident in particular. When he told me about it, I was surprised I hadn’t heard the story from my mother, since it flattered the idea she had of herself, although it was also, possibly, one of those stories she thought would set a bad example, like shooting her father. Marjorie’s sister had been in town from Ladysmith, and high tea was arranged at one of the posher hotels. It was Steven’s recollection that my mother reluctantly gathered those of her siblings she could lay her hands on and they all trooped along to the hotel. My mother didn’t like this woman, whom she sensed had always looked down on them. She referred to her not by her name, Doreen, but as “that frowsy old cow.”

True to form, said Steven, his aunt Doreen proceeded to patronize them over sandwiches and tea. At some point in the afternoon, my mother had had enough. She suggested to her aunt that they play a little parlor game popular in England at the time. Doreen was delighted. In 1967, fashions established in the old country still held sway among those who considered themselves well-to-do in South Africa. “Yes,” said my mother, who would shout when irritated but when she wanted to do real damage would lower her voice. “It works like this: everyone goes around in a circle and says their favorite curse word. I’ll start.” And summoning her pearly new accent, she looked into the eyes of her enemy and said, “Cunt.”

As Steven remembered it, the aunt actually screamed. In any case, she leaped from her seat, fled the room, and drove the five hours back to Ladysmith in one go.

• • •

THERE WILL BE NO TEARS or ululations at the gathering today. It is not the house style. Call it repression or call it self-discipline, but when brother and sister set eyes on each other after almost two decades, it is with mild, sardonic expressions. After a brief hug, Fay tells Tony to make himself useful and get up on a stool to change a lightbulb over the front door. Tony hops to it. I take a photo of him up there in a canary-yellow polo shirt, hands clasped together like a crumpled angel. When I get back from the kitchen, he has spotted something on the horizon. “Look at my fat wife!” yells Tony from his vantage point, as Liz struggles up the path, carrying beer. She gives him a look to stop traffic.

She has brought a friend along, George, who has a warm, likable air, hearty and male and smelling slightly of whiskey. I give my aunt a hug, and nodding at George, say, “I’m so glad you’ve got rid of that other awful man.” My aunt grins out of all proportion to the comment, and looking over her shoulder I see why. A man carrying a crate of beer emerges from between parked cars. I split my face in two to receive him. “Johannes! How lovely to see you.”

While Tony and Liz’s sons mill about on the lawn, cradling beer bottles and chatting politely, their parents sit beside each other at the table, drinks in one hand, cigarettes in the other. Tony points to Johannes and says, “You’d better watch out, eh,” and starts going through a long list of Liz’s ex-boyfriends who have one way or another come to sticky ends.

“Willem, taken by God. Andreus, taken by God,” says my uncle. Liz, smoking, looks as if at any moment she might shoot a poison dart out of the end of her cigarette and into her ex-husband’s neck. “God takes away those who deserve to be punished,” says Tony, solemnly.

“Shame God didn’t take you, eh,” says his ex-wife.

Tony looks martyred. “They persecute me in His name.”

“They persecute you because you’re no bloody good and a drunk.”

“Shut up, woman, or I’ll beat you up.” My uncle’s verbal tic doesn’t get any less startling. He sighs. “She left me for a better man.”

“Then what are you so big-headed about?”

My uncle grins. “It took her twenty years to find one.”

Fay turns to Liz and asks about the court case. Liz inhales deeply on her cigarette and says, “Fourteen years commuted to six.”

“What’s this?” I say. Fay says blandly, “Oh, didn’t I tell you?” Liz’s sister was shot dead by her husband last year after he discovered she was having an affair. Sentencing was this week.

“Easy on the rum and Cokes, eh, George,” says Johannes from across the table. “I don’t have a black suit for your funeral.”

“I hear you, man,” George cackles. I think, “Johannes is afraid of George, and a good thing, too.”

Johannes rubs his hands together. Someone asks after his son. “Holding up,” he says, and explains, for the benefit of the audience, that he is serving time for murder.

I look across the table at Trevor, who is not, by Fay’s account, a very enlightened individual and who seems to be struggling with the novelty of finding himself the most liberal man at the party. When Johannes starts going on about how the blacks have trashed the country, how “monkeys in the tree are called branch managers now,” and how the crime rate is way up, Trevor clears his throat and, looking nervously at me, says, “There was always a lot of crime, but we didn’t see it because it was in the townships.”

Tony is mostly oblivious to the wider conversation. He turns to his sister, and nodding at me, says, “I told her all about our dad.”

“It’s not ‘dad,’ it’s Jimmy,” she snaps, the only time I have seen Fay lose her equilibrium.

To me, Tony says, “There was something else I meant to say to you—about the twins.”

“What’s this?” says Fay.

“Yes,” I say. “My mother spoke of them once.”

Fay turns to look at her brother.

“There were twins,” says Tony, “between Mike and me. They either miscarried or were born dead.”

Fay says, “I don’t know anything about this.”

Tony says, “Ja. Mom had named them already. They were called Andrew and Trevor.”

Fay smiles in a kind of half-dazed embarrassment. “Well,” she says. “Well.”

There is more beer, more cigarettes. Everyone pushes their chairs back from the table and settles into them. “You’ll see,” says Johannes, to one of my younger male cousins. “They say it’s wrong to hit a woman. But if one hits you, it’s within your rights to hospitalize her.” My cousin scowls across the table.

“That’s right,” says Trevor. His wife, smoking stonily, turns to looks at him. “Not that I would,” he adds quickly.

“You’re very quiet,” a cousin’s wife says to me. If I had the courage, I would say it was because the afternoon seems to have turned into a meeting of wifebeaters anonymous. Because I don’t understand what this is, where men can say these sorts of things at the lunch table as if it were the most normal thing in the world, while their wives frown and withstand it. Instead, I say, “I’m fine.”

Tony, on his own unique path, clears his throat. “I come from a long line of alcoholics,” he says, before everyone at the table shouts him down. When he tries to bring up the subject of the “human intestinal fluke,” an even rowdier chorus defeats him.

“She tricked me,” he says, pointing to Liz and reaching back to some distant memory from their marriage. “She said she needed to go to the doctor, so I took her there, and when we got to the surgery they stuck a needle in me and banged me up in the drying-out ward.”

“You needed it, eh.”

“Trickery. And then she drove me home even though she can’t drive, and my head bashed against the dashboard.”

“You’re such a liar.”

Liz turns to me. “We had nothing. We were really poor. We lived near the cemetery, and in the Indian section they leave curry out on the graves, so after they’d left we’d go and steal the food.” She knows how this sounds and smiles to acknowledge it, taking a deep drag on her cigarette. She says, “The dead can’t chase you.”

Before she leaves, Liz turns her electric-blue eyes on her ex-husband. “Man, look at the hole in your trousers,” she says. Liz sighs, as if in the face of an unpleasant but irresistible force. “Give them to me and I’ll mend them for you.”

My uncle looks at her tenderly. “She’s been in this family as long as any of us, eh,” he says.

After everyone has left, I take a photo of the empty fridge. Fay and I sit side by side on the sofa, exhausted. Notwithstanding Johannes’s various contributions—“Rough,” says my aunt, shuddering, “rough”—we declare the afternoon a success. I’m not sure what criteria we’re judging this by, until the next day, when Liz rings Doreen, who rings me straight afterward, giggling. “Liz said you all had a nice time yesterday,” says Doreen, and flattens her accent to do the impression. “‘It was nice, Dor,’ she said. ‘There were no fights and no one got drunk.’” Doreen laughs uproariously.

Fay and I agree. “It was all just so civilized.”

• • •

I HAVE NOT FOUND the prosecutor. Nor the arresting officer. And there are friends of my mother’s I still haven’t seen. I have reached saturation point, but there is one final connection I want to explore. The person in question is dead, but she was very important to my mother. I want to know something of her.

There are four or five Sosnoviks in the Johannesburg phone book. The first one I call says with surprise, yes, he knew a Sima Sosnovik. She was his late aunt. A couple of days later, I drive to his house, a large, imposing building in one of the nicer suburbs. He is a lawyer, I think. I say hello to his wife and we repair to his study, where I repeat what I said to him over the phone; that my mother and his aunt had worked together in the 1950s; that Sima was important to her, and I’m interested in that period. I am aware that as an explanation, it doesn’t quite cover it, and he looks at me oddly but is game to help. “I think your aunt was some kind of role model to her,” I say.

“Yes, well, she was a forceful character, in a quiet way,” he says. “Not a shouter, but forceful.” He tells me she was born the fourth of seven children in Bialystok, which at the time was part of the Russian empire. The family moved to South Africa in 1920, when she was ten. Her father was a teacher of religious studies. She started out as a bookkeeper in a fish shop in Melville. “I wish I had a photo for you,” he says. “She had reddish hair.”

In the late 1940s, she emigrated to Australia but returned two years later. “She was very confident. She spoke slowly but with emphasis. She had enormous integrity and a very dry sense of humor. Dry and sarcastic. She was the brightest in the family.”

He gestures helplessly. “She had a relative called Grevler, on her mother’s side. I think he won the Delagoa Bay Lottery.”

Sima’s nephew gets up and goes digging in a file. “I can give you a copy of this,” he says. It is a short piece of writing she did when she returned from Australia.

“Thank you.”

“She died in 1958 of cancer of the liver.” The year of the High Court trial. No wonder my mother’s thoughts turned to suicide that year.

That evening, I sit outside on the terrace and read the piece of writing. It is a sentimental account of her childhood, how each of the seven children had an allotted role: the mother, the baby, the rebel, the caretaker. She was the rebel, in the middle, fighting to stand out. After two years in Australia, she saw she had made the wrong decision. She came home to Johannesburg, she wrote, with the realization that after all her protestations of independence, what mattered most in the world was family.

• • •

STEVEN HAS MOVED to another town farther east along the coast, a not-so-chichi resort where he is staying with friends. I go down to see him one last time. By chance, it’s April 27, the anniversary of South Africa’s first democratic elections, christened Freedom Day. We walk along the beach for an hour before sunset, the sky pink and translucent, pebbles clacking beneath our feet as Jesse and Jezebel run ahead of us. Every now and then they skid to a halt and whip over to bite themselves.

At the driftwood, we stop. It is burned white by the sun and shaped like a bench, curving up from the beach in two ribby arcs. We sit on it and watch the dogs. Steven says, “I was headed for a life of repressed mediocrity. I didn’t want to repeat his pathology, be a drunk. I thought, ‘If I’m going to go wrong, let me do it my own way.’” He doesn’t believe in closure. “I have sufficient healing.” My uncle smiles. “Like sufficiently free and fair elections.” He says, “If I hadn’t had her love for the first ten years, I wouldn’t have survived.”

• • •

ON THE LAST DAY, I drive around the neighborhood. The trees are burned orange at the edges. Through the flat, still air a wood pigeon calls. You could die from an afternoon like this, I think. I draw level with the car park at the end of the street and wind down the window. Siya puts his hand through it and grips mine. He is wearing black fingerless leather gloves. “Stay cool,” he says. His guitar is slung around his back and his beanie is as high as the Cat in the Hat’s. “Keep smelling the air and feeling the sunshine.”

“See ya, Siya,” I say. Our fingers grasp and release.

I am so sure I will be back in Johannesburg before long, I have left a large pile of books in the closet. I have said good-bye to Fay in a deliberately casual manner because I will be seeing her again soon. On the plane home I am ecstatic. I did it. I have done it. It is done.

I don’t go back.