Lost in Translation

I was in my late twenties and fairly innocent of Spain in particular and Latin culture in general when I first went to Spain, though I had earlier been posted to our embassy in Argentina. On arrival in Buenos Aires I heard everyone in the street referring to “Asia.” I thought some catastrophe had struck that continent and asked people “What’s happening in Asia?” They looked at me strangely. I bought all the newspapers at a kiosk on the Calle Florida, the city’s lovely pedestrian only street, and went into a coffee shop to read them. I could find nothing of significance about Asia in the newspapers. Days passed before I realized that how Americans say “Asia” is exactly how Argentines pronounce “ella” (she). Spaniards say the word something like “eya.” The double “l” is a “y” sound in Spain, in Argentine more like a “j”.

Argentines today, after my years in Spain, routinely want to know if I learned my Spanish in Spain.

“Why do you ask?” I reply.

“Because,” they say, “you speak with a Castilian accent.” Of course, Spaniards think I have an Argentine accent. I tell citizens of both countries that my accent is actually pure New Jersey.

Differences in accent and pronunciation among Spanish speaking countries are paralleled by differences between the meanings of words. One of the first things I learned in Spain was that the verb “coger,” never to be used in polite company in Argentina, is perfectly acceptable in Spain. In Argentina it means, plain and simple, “to fuck.” In Spain it means to take hold of something. So, even within Spanish, there are important differences from country to country, and not just in accent or pronunciation. This should not have surprised me. In England, people are still learning to speak the proper English we in the “colonies” speak. Quite apart from their strange accents, to this day the Brits confuse “lorry” with “truck,” “petrol” with “gasoline.” Perhaps we Americans should send over cultural missionaries to straighten them out.

We must also contend with the fact that the same word may, in English and Spanish, mean very different things. I first became aware of this upon arrival in Madrid. Searching for a place where my family might live, I located a house in the Madrid neighborhood of Colonia de El Viso. An American family had previously lived there, the one that told me about the Romanian Nazis next door and left the ill-fated Pipo with me. Just before my prospective landlady and I signed the rental agreement, she told me that that family had been “muy informal” (translated literally : very informal).

“Glad to hear it,” I told her.

She looked at me searchingly, her pen hesitating over the paper. Later I would learn that celebrating my predecessor’s informality had nearly sabotaged the house rental. Americans can’t imagine informality as anything but positive. What I thought of as easygoing and sincere she thought of as bad manners and incorrect, unreliable behavior.

Of course, the incident with my landlady occurred back when Spanish culture was in the grip of a very conservative church and the Franco dictatorship. Informality was not in the least prized. The Spain I knew in the 1960s was a stiff, buttoned up place. Men of any stature never went out of doors without wearing a jacket and tie, even on the hottest summer day. Neighbors on my little street never knew what to make of me when I came home from work at the embassy, took off my suit, and went outside in torn jeans and a dirty T-shirt to work on my car. For them, there were people who worked on cars and people who didn’t; it was a matter of social class. What was I, an American diplomat, doing under my car, oil dripping down on my face?

Americans have always believed in a classless society. To put it another way, virtually everyone in our country considers themselves middle class, from the homeless person in the street to Bill Gates. We fought for our independence from Britain partly to rid ourselves of class distinctions. It is something of a myth that we succeeded, but we hold to it as an ideal.

Jeans, the national “uniform,” is an expression of that ideal. With everyone wearing jeans it is largely impossible to discern social class. When I was a boy jeans were called “dungarees.” The first part of that word, “dung,” refers to manure. Dungarees were the trousers one put on to emulate cowboys, one of whose regular tasks was shoveling manure. Thus “dungarees” implied people not too proud to work with their hands but still middle class. “Jeans” or, even more so, “designer jeans”—jeans with some celebrity’s name stitched on one’s rear—are virtually identical to dungarees but “classier.” Or so those think who pay so much money for them. The most fashionable of these jeans come “stressed” from the store, appearing to the uninitiated as if they were plucked from a dumpster. And now the designer, Ralph Lauren—that clever devil—has come out with a new line of very expensive jeans called “dungarees.” We’ve come full circle.

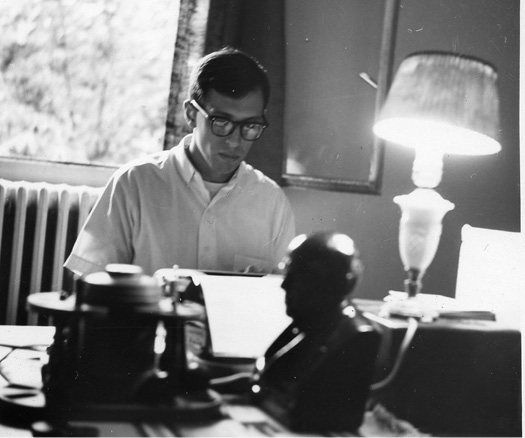

The author seated at his desk at home in Madrid working on his doctoral dissertation on Domingo Faustino Sarmiento and the United States, eventually published by Princeton University Press. In front of him is a bust of Sarmiento.

Today, everywhere in the world—with the exception of North Korea, where they are banned—jeans are worn. They are more of a symbol of American influence on universal culture than is McDonald’s. However, in the Spain in which I lived, virtually no one wore them. And few were informal, utilizing either meaning of that word. It is testimony to how much democratic Spain has changed since my embassy years that everyone wears jeans and occasionally now I hear “informal” used positively. Regardless of the words utilized, it could be argued that today Spain is more informal than the United States.

I’ve noticed that Spaniards much more readily than when I was with the embassy use the familiar “tu” instead of “usted” when saying “you.” Then it tended to be restricted to family and close friends. Also, Spaniards today often begin calling me “Michael” on our first meeting—or even before, in correspondence—and that is another sign of American-like informality. Whether a good idea or bad, this is one reason this American feels so much more comfortable in Spain than he did in the past. Let us hope, however, that as Spaniards increasingly use first names, this informality will not be exploited, as it is in America, by those trying to sell you something you do not want—such as another insurance policy.

One thing that took getting used to in Spanish as spoken in Spain (generally called “Castilian” now, to distinguish it from the various regional languages that were banned during the Franco dictatorship) is how so many Spanish words that appear to have English equivalents seem much stronger, if not exaggerated, if said in English. We Americans must be careful in English to remember that these words do not have the same force or even meaning in Spanish, where they are everyday words. Literal translation is referred to in Spanish as “traducciones de vaca” (translations made by a cow). For example, there are the exclamations “estupendo,” “magnifico,” “barbaro.” If one were to use these words in English, translating literally, they would be “stupendous,” “magnificent,” and “barbarous,” words used only in the most extraordinary circumstances. Also, for us, something barbarous is an atrocity committed by barbarians, while for Spaniards, “barbaro” is usually a colloquial expression of delight or of approval. To the American eye and ear, much of Spanish, were it to be translated literally—always a mistake—would seem infected by inflation. These are examples of the “false friends” idea in translation—identical or similar words that appear in two languages but do not mean the same thing, sometimes even, quite the opposite.

My favorite in Spanish is “constipado.” I thought it very curious during my early days in Spain that many people, especially in winter, would go about publicly announcing that they were “constipado.” I was embarrassed for them and would look away. What a private, if not gross, thing to announce! What they meant was not that they were constipated but that they were suffering from colds, that they were, if you will, stuffed up at the other end of their bodies. There is a different word entirely in Spanish for constipated.

A conference on Spain and the United States organized by the author at El Escorial Monastery. On the right is Julian Marias, Spain’s most distinguished philosopher at that time and a member of the Spanish Royal Academy. Marias also wrote several books on the United States which the author, in shirtsleeves in the picture, edited for publication in English.

Another word in Spanish that tickles me is “embarazada.” It means pregnant, not embarrassed—though perhaps at one time it may have been a more delicate way to admit that one was pregnant if that was not desired.

I am reminded of the book by Guy Deutscher titled Through the Language Glass: Why the World Looks Different in Other Languages. At one point Deutscher writes that language “actually organizes habits of mind and influences perceptions in different cultures.” I can testify to that. There are things I say every day in English that have no Spanish equivalents and vice versa. Thinking in another language is the only way to fully enter a culture.

To translate from another language one must fully understand the culture out of which its words have emerged or you will be translating literally, usually a mistake. I’ve always wondered what Hemingway had in mind in For Whom The Bell Tolls when his characters, especially Robert Jordan and Maria, speak in a kind of pigeon English, supposedly translated from the Spanish and laced with “thees” and “thous” Was Hemingway trying to communicate some of the flavor of Spanish in the English or just translating literally from the Spanish he would have placed in his characters’ mouths. Frankly, I don’t know. I remember reading the novel before I knew Spanish and finding the language charming. Now it seems rather corny.

In April of 2011 a lecturer at Princeton University of Spanish background, Antonio Calvo, killed himself after he had been suspended from the Spanish Department for reasons not entirely made public. But one reason he fell into disfavor seems to be his use of common expressions that are not in the least offensive in Spain but, when translated literally into English in the United States were taken to be insults and even threats. It would appear that misunderstandings from one language to another can, under certain circumstances, be dangerous, if not lethal. Humor, for example, is sui generis, limited by time and place. Today’s joke can be tomorrow’s insult. I have learned the hard way that what was funny to an earlier generation of students at my university is not funny today and, not always happily, I have tried to make adjustments.

Also, cultures, and the languages that embody them, are forever evolving and changing. For example, there is in progress in the United States a continual semantic redefinition of black people. When I was a child my parents would refer to “colored people.” Coming of school age, I learned that “colored people” was a racist term and that the word “Negro” should be employed. With some discomfort, my parents agreed. But just having settled on “Negro,” they and I were informed that this word was now racist and one should say “black”—with much discussion over whether the word should be capitalized or not; colors are normally not capitalized, ethnic groups are. Black people are obviously both though, of course, none of them are actually black. Brown, maybe, but not black.

There were two other ironies about “black.” First, “black” was the term used during slavery days, so why was it now being championed? After slavery was abolished, “colored people” was actually considered a step up from “black.” There was, and is, after all, the important National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Second, “Negro” means “black” in Spanish, so while we in the United States could switch to “black” from “Negro,” being two different words, how could Spaniards be au courant in describing this group of Americans, since they had only one word, “Negro,” at their disposal. Having just settled down with “black,” I was informed that the correct term was now “African-American.” Which was fine with me, but I wasn’t sure how to refer to a white friend of mine who had emigrated to the United States from South Africa. Was he not an “African-American?” Nor did I know how to refer to immigrants from African countries north of the Sahara, mostly Arabs, who are also Caucasians. Were they not also “African-Americans?” And what about black people who emigrate to the United States from the West Indies? To the chagrin occasionally of people who consider themselves African-Americans, they insist they are “Caribbean-Americans.”

Recently, just after I had decided, despite arguments to the contrary, to adopt “African-American,” sophisticates latched on to “People of Color” as the new term—which refers primarily to black people but also to anyone not classified as “white.” There are several things wrong with this expression. First, with the possible exception of albinos, I have never seen a white person; we are all shades of beige or tan or brown. Second, every human being is colored something. And, third, “People of Color” sounds mighty like the very “Colored People” term I gave up as a child so as not to be thought of as racist. If we in the United States are confused about what terminology to use, one can only imagine how the issues I raise here—simply what to call a certain group of Americans—must puzzle Spaniards trying to discuss race in America, not to mention those translating from English to Spanish.

How should one racially designate President Barack Obama? His black father was from Kenya, his white mother grew up in Kansas. A Spanish friend asked me why we don’t refer to him as “a mulatto,” but Americans long ago gave up this word as a vestige of slavery and as particularly offensive because it was derived from the fact that mules are the product of the mating of donkeys and horses. It is interesting how in the presidential campaign of 2008 there were some Americans who considered Obama “too black,” others who considered him “not black enough.” This was primarily not a reference to color as to politics and culture. Often our problems and misunderstandings as human beings stem from simply not having the words to describe certain people or situations. Proper attention to semantics might very well preclude, or at least limit, human dissension and even warfare.

There is a movie I like whose entire plot hinges on a simple mistranslation: The Ballad of Gregorio Cortez, produced in 1982 and starring Edward James Olmos in the title role. Cortez is a Mexican-American accosted by the local sheriff, who is looking for a horse thief. Cortez is asked if he has a new “caballo” (which actually means “stallion,” not horse). He responds “No, I have a new yegua” (a mare). The sheriff’s deputy, with only a bit of Spanish and unaware of the male-female gender distinction between horses, tells the sheriff that Cortez refuses to cooperate in the investigation. Gunfire breaks out, and there will be many deaths before anyone comes to understand that, when it comes to an unfamiliar language, or one not fully mastered, a little knowledge can be a dangerous thing.

There is a book I confess to not having read, but I love its title: El Delito de Traducir (The Crime of Translation) by Julio-Cesar Santoyo. Translation is something of a “crime,” come to think of it—albeit a necessary one. I’ve translated one book from Spanish into English without once feeling guilty that every word in that translation is mine—as if I had such callous disregard for its author as to feel free to “plagiarize” his work without apology. Let’s face it: reading a book in translation is not reading the same book as the original. For example, reading a novel in English that was originally written in Spanish or some other language is to read a novel written by a translator based on the ideas of the original writer.

And this is, under the best of circumstances, a translation by someone both extremely knowledgeable, careful, and talented—an artist, since translation is primarily an art not a science. Of course, the “artist” part can be pushed too far: translators make up things—sometimes whole sentences, even paragraphs—that weren’t in the original version. I have had writing of mine appear in various languages and, since the only language I know well is Spanish, it’s only the Spanish editions of my work where I am able to read the translation before it appears in print, and I sometimes discover anomalies if not downright falsehoods and am able to point them out to the translator. I can’t, for the most part, do this in other languages. Once something of mine appeared in Japanese. I’ll never know to what extent the Japanese translator created a text entirely akin to what I had written or had used her imagination excessively.

Even names have different significance in different cultures. A certain name took a great deal of getting used to when I first arrived in Spain. Though I am not a Christian, I initially thought Spaniards who named their son “Jesus” must be guilty of blasphemy. Until recently in the United States, most Catholics have been of Irish or Italian or Polish origin, and few, if any, American Catholics would ever name their son “Jesus.” They reserved this name for a being they considered divine. How could an ordinary boy be named Jesus? There was, for them, only one Jesus. Americans are beginning to get used to the name in common usage because of vast migrations from Latin America, which include a fair number of males named Jesus, but the name still seems strange to many of us.

I’ve asked Spanish friends with the name Jesus whether they feel any particular obligation to be well behaved. They laugh and say, “It’s just a name,” or “I’m a sinner like everyone else,” or they joke: “Ironically, with this name I can get away with more.” Still, the name Jesus, and its pronunciation in Spain, which sounds like “Hey Zeus” to the American ear (in English we say something that sounds like “Jeezus”) takes some getting used to.

A personal note in this regard. My youngest child’s name is Joshua. When he was born, Catholic friends would say, “You’ve given your son a very Jewish name.” That we had, though a very Christian name as well. Jesus and Joshua are the same name in different languages. Indeed Jesus’ name was not Jesus, it was Yeheshuah. Jesus is Greek for Yeheshuah which is Hebrew for Joshua. I’ve always wondered why my Christian friends do not call Jesus by his own name instead of its Greek translation. It’s a little like a certain Jose emigrating from Spain to the United States and deciding to call himself “Joseph” or “Joe” instead of sticking to Jose or if I were to move to Spain and insist my name was not Michael but “Miguel.” Though if I may be so bold as to suggest, not calling Jesus by his proper name would seem to have, or should have, vastly greater significance to Christians.

Also sounding strange to Americans is when they meet Spanish men whose names are Jesus Maria or Jose Maria. How can a man carry the middle name “Maria,” a woman’s name? John Steinbeck had fun with this in his novel, Sweet Thursday (1954), one of whose key characters, of Hispanic background, a certain Jose Maria, he calls “Joseph and Mary.” The same problem for Americans applies to Spanish women with the name Maria Jose or Maria Jesus. How can a woman have a man’s middle name such as Jose or Jesus? We do have plenty of women named Mary Jo in the United States. Perhaps that was originally a shortening of Maria Jose. Mary Ann (Mary’s mother supposedly having had the name Ann) might be another common example, though Ann is, of course, another feminine name, not a feminine name followed by a masculine one. Americans do not associate anything religious with such names any more than do Spaniards.

Forgive my vulgarity, but there is a word in constant use in Spain today that I wish to discuss, “coño.” I don’t recall its universal use during my embassy days, but today it is everywhere and in every social context. If literally translated and utilized by a man in the United States it would cause his estrangement, if not permanent exile, from every woman in his life. It is probably our most taboo word in English: “cunt.” Try using that word in the United States, whether in a small town in Iowa or in New York City, and you may not live to see another day. If one were to refer to a woman as a “cunt” this would be like calling her a whore multiplied one hundred times but also with specific derogatory reference to her genitals or the suggestion that she is nothing but her genitals. But, in Spain, “coño” is casually used even in polite society and with a hundred different meanings and, at the same time, none at all. People greet their best friends using this word or use it regularly at the beginning of sentences. It also seems to be a common exclamation, of little significance, such as “Oh, my!”

I have tried to explain this usage to key American women in my life—said that “coño” in Spain is generally not in the least offensive. But these efforts to demonstrate cultural relativism have failed miserably. Even mentioning that Spanish women friends—most of them professors and writers and quite as feminist in their orientation as anyone in the United States—do not seem at all offended by the constant use of “coño,” has had no effect. I’ve asked Spanish women why they are not offended by this casual reference to female genitals, and they have laughed at me. “Coño may once have meant that,” they tell me, “but it doesn’t any more. It doesn’t mean anything and certainly not anything offensive to women.”

Ah, yes, language evolves. So much so that a Spanish scholar, Juan Manuel de la Prada, has written a respected book, in multiple printings, titled—you guessed it!—Coños (1995), with graphic illustrations throughout created by a distinguished female artist. The book is, broadly speaking, about Spanish culture.

Even my saying that the use of “coño” in Spain usually has no more negativity to it than, say, Argentines beginning their sentences with “Que se yo” (What do I know?) or Americans beginning their’s with “Like” or “You know” or “Man” has not helped me with the American women in my life. Nor has it helped to point out that “coño” has no more significance than that plague infecting the speech of young American women these days, who cannot seem to say anything not preceded by “Oh my God” or in their e-mails and text messages, “omigod” or simply “O. M. G.” That I know of, this expression is never a sign of religious devotion. It could, in fact, be regarded as a violation of the Third Commandment, to “not take the name of the Lord thy God in vain,” but no one in the United States gives this a moment’s thought. We have yet to hear preachers of various faiths inveighing against this usage from their pulpits. If they do, it will, no doubt, leave a host of young women temporarily mute.

Spaniards seem to forever be saying “coño” this and “coño” that, women employing it almost as much as men. During a recent trip to Spain I was actually greeted by an old friend who went much further. “Coño,” he said, advancing to embrace me, “me cago en tu puta madre” (which, if translated literally, means, “Cunt, I shit on your mother the whore.”). My mother no longer being alive, my feelings were a little less violent than they might have been. And I tried to remember that the great Spanish film director, Buñuel, always insisted that Spanish was the most obscene language of all. Still, it wasn’t until well after my friend explained that this was the ultimate greeting of endearment between friends that I was able to give up my strong desire, if not obligation, to strangle him on the spot.

I also realized that, in English, we sometimes use similarly vulgar terms in greeting friends. We may say, “How are you, you old son-of-a-bitch?” Or, much stronger, “How’re doing, motherfucker?” Obviously one might use such terms in great anger, but, like “Coño me cago en tu puta madre ,” they are usually expressions of affection. In a friendly context they don’t mean that your friend’s mother is a dog or that you are accusing him of having sex with her, but that you feel comfortable enough with him to use vulgar and even highly insulting words as testimony to your deep feelings for him and the mutual trust of friends.

Years ago, my wife and I were invited to dinner by Spanish friends at their home. The word “coño” flew about the room at regular intervals, despite the fact that the couple were serious Catholics and had both once served in the church. When our hosts were in the kitchen preparing to bring food out into the dining room, my wife turned to me and asked, “Are they saying what I think they’re saying?”

I tried to explain that “coño” as used in Spain means something other than “cunt” if it means anything at all, that this is a common expression or interjection or exclamation, occasionally even a term of endearment, that its public expression virtually never has, in the Spanish mind, anything to do with women’s genitals, that “coño,” though I can think of no other way to translate it into English, simply does not mean “cunt” in Spain. She was, nevertheless, furious.

I could not begin to convince her that translating “coño” literally is incorrect, if not dangerous. It was all I could do to keep her from dashing out the door of their home. It remains a bone of contention between us to this day. She loves Spain as I do but finds the constant use of “coño” insupportable.

In Oslo, Norway a few years ago I went to see the wonderful 2003 Spanish movie Mar Adentro with Norwegian friends. In this film Ramon Sampedro, played by Javier Bardem, has been paralyzed from the neck down for almost thirty years and desires to simply end his life. Friends wish to help him, but he wants legal sanction so they will not be accused of a crime. The movie is based on an actual case that long wended its way through the Spanish courts.

At one point in the movie a priest who is similarly paraplegic, visits. He wishes to convince Sampedro that he has much to live for. The bedridden Sampedro is upstairs. The priest remains downstairs because it is impossible to transport his wheelchair above. In their shouted exchange, the priest, like any other Spaniard, utilizes “coño” as part of normal, colloquial Spanish. “Lord,” I thought, “priests too!”

After the movie I asked my Norwegian friends if they were offended by anything in the priest’s speech. While I had seen the film in Spanish, they had read the Norwegian subtitles. They knew of nothing offensive in what the priest said. “What did he say?” they demanded to know. I tried to explain as delicately as I could. They looked at me strangely as I, somewhat embarrassedly, told them about “coño” and “cunt.” They assured me that there was nothing like that in the priest’s speech as translated into Norwegian. At first I thought this might have been the work of Norwegian censors, but I soon concluded that those who crafted the subtitles wisely realized that the manner in which “coño” is generally used in Spain should not translate as anything sexual or offensive in Norwegian or any other language. I have since seen the movie with English subtitles and can report that the same thing is true of them as of the Norwegian ones, another example that translation and culture are intimately linked.

Finally, there is a Cuban restaurant in the town of Hoboken, New Jersey called La Isla (The Island) where I occasionally go with a daughter of mine who lives in that city. All the employees in the restaurant, men and women alike, wear T-shirts that simply say “ño” on them. I asked our waiter what this means. He told me that “ño,” as I had begun to suspect, is short for “coño” in Cuba and that its usage is a source of national identity and even pride. I have attempted to share this further information—the Javier Bardem movie and the T-shirts in La Isla—with my wife but she refuses to hear anything about it. The same is true of many, though not all, American women friends and colleagues with whom I have discussed the issue. I write about it here as an example of cultural contrasts. Spaniards will understand what I am talking about. In my own country I hereby abandon the cause as, at least for the present, hopeless.

A related matter: in American English we have a host of words in common usage that were “dirty” in origin, or at least unmentionable in polite society, but have become parts of everyday speech just as in Spain. For example, when my students in the United States do not like something or someone they say “That sucks” or “he sucks” or “she sucks.” When I explain to them that this term originated in expressions disparaging those who perform oral sex, they think I’m crazy. The connection that was once there has been lost.

The word “jock” is another case in point. At first, jock was short for jockstrap, the device protecting men’s privates while playing sports. As a young athlete I never used that word in mixed company, nor did anyone else I knew. Later, “jock” came to mean any male athlete. But now it is used quite as frequently for female athletes, who never wear jockstraps. Today’s young people obviously no longer associate the word “jock” with “jockstrap.”

I should also report that such expressions as “Fuck you” “Oh, fuck!” and “fucking” as all purpose verbs, adjectives, adverbs, or exclamations have become almost universal in the United States, used, like coño, for virtually everything but sex, and, in becoming so widely used, have largely lost their power to offend. However, Americans were more than a bit surprised when former Vice President Dick Cheney told Senator Patrick Leahy of Vermont, right on the floor of the United States Senate, to “Go fuck yourself!”

I do think Americans curse utilizing religious terms more than Spaniards do. “God damn it!” or “Go to hell!” or “Jesus Christ!” are common expressions unconscious of religious significance or blasphemy except among fundamentalists and strict Catholics, whereas I have the sense they are taken more seriously in Spain. I do not hear them used often there. Each culture has its distinct taboos, and that’s fine. We just have to be careful not to assume they are applicable elsewhere.

Worth mentioning are the differing challenges in learning Spanish and English. Except for the silent “h,” the fact that all nouns in Spanish have gender (la casa, el libro), and the fact that the Spanish language “sadistically” offers two different verbs for the all important “to be” (ser and estar), English is harder to learn because it isn’t, like Spanish, phonetic. For example, hearing the Spanish word “bastante” for the first time, one would know how to spell it. But pity the poor English learner when faced with the equivalent word, “enough.” We pronounce it “enuff” but spell it in a way that looks nothing like it sounds. Not to mention that a considerable number of words in English sound alike, and in some cases are spelled identically, yet have different meanings. For example, “bear” (as in to carry), “bear” (the animal), “bare” (to be naked) and even the way southerners pronounce “beer” (the drink). If Hispanics learning English refused to learn the language until some phonetic rationality had been injected into it, I would sign their petition.

There is a related subject I want to discuss now, not language per se but body language. There is much that is lost in translation between Spain and the United States in how we comport ourselves in public.

Spain initiated me into being physically closer with people. In those days, American men never embraced. It was considered, well, unmanly. But living in Spain I was soon a great aficionado of the abrazo. It seemed a lovely thing for men to be physically intimate with male friends and relatives just as women were with other women—without this suggesting anything regarding sexual orientation.

I did get into difficulties with the abrazo when I first returned to the United States after my years at the Madrid embassy. My father and brother picked me up at Kennedy Airport in New York. As I advanced towards them, arms open, they backed up, alarmed. They must have been wondering what had happened to me in Spain that I intended to embrace them rather than to shake hands. Of course, these days in the United States, partly because of Latino influences, many men embrace. As mentioned elsewhere in this book, President Barack Obama is a great embracer or hugger, which has served to further popularize the abrazo.

Spain also taught me to kiss in a way I never had before. Some American men will socially kiss women, but it is always on one cheek. I can recall the first time I was introduced to a woman in Spain and proceeded to kiss her on one cheek. Our noses smacked into each other as I retreated and she moved toward the kiss on the other cheek. The blow brought tears to both our eyes. “Que bruto!” (what a brute you are) she exclaimed. I do hope that woman has forgiven me by now.

I think that before my Spanish experience I always kissed my daughters on the cheek but never my sons after they were more than a few years old. Spain changed that. Ever since, I routinely embrace and kiss all five of my now grown male and female children on the cheek, sometimes on both cheeks. In doing so, I fly in the face of traditional American custom. I remember when, as a boy, an Italian-American friend of mine complained of the embarrassment his father caused by publicly kissing him hello and goodbye. As my friend put it, “I wish he would cut it out. I’m an American.” This fellow used to complain too about the dripping meatball sandwiches his mother sent along with him as his school lunch instead of the peanut butter and jelly sandwiches we “true Americans” always ate. Actually, I rather envied him his dripping meatball sandwiches. They surely tasted much better than my peanut butter and jelly sandwiches. They also seemed to complement the kisses bestowed on him by his father.

I guess that after so many years of experience of Spain I am a bit less “American” than I once was, certainly in terms of publicly expressing affection. However, I recall an incident when I was seeing my son Jeffrey off at New Jersey’s Newark Airport. The same son who was in Dr. Zhivago as a child, he was then a professional ballet dancer, magnificently handsome and with a perfect body (if a father may brag). At first I had been disappointed in his dancing career, wondered whether it was sufficiently manly. Soon enough, however, I became a dance aficionado and found myself proud of his strength and grace. Ballet dancers aren’t just performing artists; they are the world’s greatest athletes.

Before Jeffrey went down the tunnel to his plane (this was before 9/11; travelers could be accompanied by non-travelers to their gates) we embraced and kissed each other on both cheeks. I stood there for a moment and then looked around me. People seemed to be gazing at me. Or I thought they were. Perhaps they weren’t and it was just that elements of internalized homophobia I would have denied harboring had briefly reappeared in my thoughts. I imagined these people saw me as this middle aged guy saying goodbye to his young lover. Comic though the thought was—this was my son after all!—I was ashamed. Certainly, a father ought to feel comfortable about kissing goodbye a son of any age in any place in any country.

I recovered from my chagrin and, today, I’m a great hugger and a great kisser—females, males, children, old ladies, dogs, readers of my books—and my life is considerably the richer for it. I like doing these things so much I may already surpass my Spanish friends. If so, Spain’s attractive, infectious culture is to blame.