Introduction

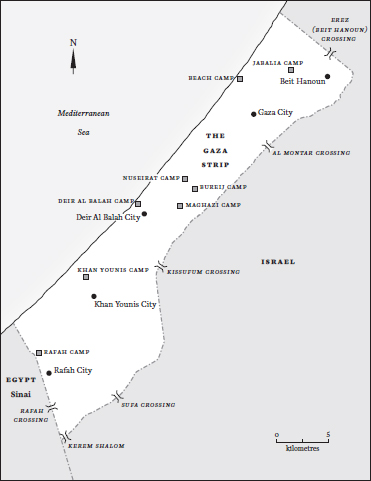

IN PERFORMING their assigned gender roles as life-givers, keepers of family tradition, and culture bearers, Palestinian women have created, practiced, and continue today to practice forms of resistance to generations of oppression that are largely underreported and unacknowledged. This is the case in virtually every part of historic Palestine, but it is particularly true of the Gaza Strip. The Gaza Strip, often referred to simply as “Gaza,” is a small, hot button territory on the eastern shore of the Mediterranean Sea, 40 kilometres long, with a width that varies from 6 kilometres in the north to some 12 kilometres in the south. Despite its significance as the heartland of the Palestinian struggle for freedom and rights, the history of the place and its people is often deformed by simplified discourses or reduced to a humanitarian problem and a contemporary war story. The recurring pain and loss its people face are offset by life and vibrancy, by playful and earnest children, by ambitions and dreams.

Around 1.4 million refugees1 live inside the Gaza Strip (forming some 18 percent of a worldwide total of 7.9 million Palestinian refugees2). For Palestinians and Palestinian refugees in general, but especially for those living in Gaza, the central event in the narrative of their lives is the Nakba (the 1948 catastrophe), which led to the dispossession of the Palestinian people, displacing them, appropriating their homes, and assigning them the status of “refugee.” In the history of Palestine and Gaza, the catastrophe of collective dispossession is a shared focal point around which they can congregate, remember, organize, and “struggle to reverse this nightmare.”3 Rather than allowing the memory of the Nakba to dissipate, time has deepened and extended the communal consciousness of sharing “the great pain of being uprooted, the loss of identity.”4

In his anguished plea for the departure of “those who pass between fleeting words,” the Palestinian national poet Mahmoud Darwish calls for the departed to leave behind “the memories of memory.”5 Darwish’s poem is a cry for the value of memory, for the deployment of words, stories, and narratives in the battle for justice. Words and memories, Darwish said, matter. But he also recognized that dispossession is a function of the Palestinian national story. Among the list of items stolen are the blueness of the sea and the sand of memory. These phrases could be references to numerous sites in historic Palestine, but Gaza would have to be among them. There, the blueness of the sea is still available to Palestinians, but the sands of its beaches offer little comfort to those who remain uprooted from the soil of their ancestral homes. (Among them, one of the editors of this work who grew up a short distance from one of Gaza’s most famous beaches, al Mawasi, looking at it from among the dense, grey crowd of houses that make up the Khan Younis refugee camp.)

The Gaza Strip.

In Palestinian legal, political, social, and historical discourses, the Nakba constitutes the key turning point. The rights to which Palestinians are entitled under international law are the shifting benchmarks these discourses and narratives seek to restore. The memories that they struggle to keep alive are sites of resistance against the obliteration of history and the erasure of a vibrant culture.

Gaza’s History

In putting together this series, we seek to bring attention to just a few strands of the myriad individual narratives comprising the Gazan tapestry. As we explain below, each story has been woven into the series in nuanced awareness of how it relates to the larger context unfolding at the time.

This larger story is multi-faceted. However, its discrete and varying facets share a common sense of abandonment. Virtually all Palestinians have been abandoned and, in fact, suppressed. That this suppression has taken place through the actions of a group of people who themselves were abandoned and oppressed is one of the most painful ironies of this conflict. When Palestinians cry from the pain of their Nakba, this cry comes directly as a mirror of the pain of the Jewish Holocaust—the pain of the Jewish people escaping concentration camps and genocide in Europe. There were cases of people who wanted shelter, security, and freedom. And there were cases of those driven by the Zionist ideology, which, since the days of Herzel and the Basel Congress of 1897, placed a premium on securing a homeland for the Jewish people above all other considerations, including the dignity and protection of Palestinians.

Palestinians have been abandoned by the world, whether by colonial protectorates, like Britain, who signed over “their” land to the Jewish people through the 1917 Balfour Declaration—violating the well-established legal maxim that nobody can give what he does not possess—or by some of today’s Arab regimes, mainly the Gulf countries led by Saudi Arabia, who view their common enmity for Iran as justification for steadily siphoning off the rights of Palestinians. The latter creates a sense that the Palestinian cause has lost its status as cause célèbre of the region and that the Palestinian people are becoming mere footnotes in regional politics. Perhaps most tragically of all, they have been abandoned by both recent and current Palestinian leadership, who have signed peace deals without addressing the core issues of their struggle: the right of return and the 1948 Nakba.

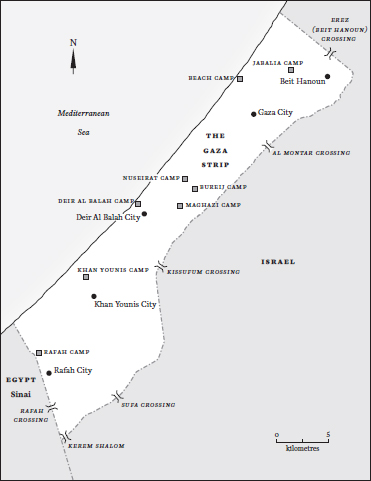

Palestine, 1947: districts and district centres during the British Mandate period.

It is no wonder, then, that a second strand of the Palestinian narrative is that of alienation from, and lack of faith in, the political structures that should supposedly achieve legitimacy for the rights that Palestinians yearn for so passionately.

Gaza, from a birds-eye view, has always been subject to abandonment and suppression. Its location is of strategic significance: a crossroads between Palestine and the lands to the south (Egypt), Israel (today) to the north, and Europe to the west. The future capital of the unborn Palestinian state, occupied East Jerusalem, is just a short hour-and-a-half drive to the east. Under the British Mandate (1922 to 1948), Gaza was one of the six districts of Palestine. When the United Nations voted to partition the country in 1947, Gaza was to be one of the main ports for the future Palestinian state. Successive Israeli governments have consistently deemed the place and its people a problem and perpetual security threat. In idiomatic Hebrew, the expression “go to Gaza” means “go to hell.”6 Even within the Palestinian narrative, Gaza’s history has been pushed into the margins.

The UN library contains a vast body of documentation of the processes and consequences of Palestinian dispossession and occupation, whether economic, social, or legal. Alongside the catalogue of resolutions concerning peace, statehood, and rights (UN Resolutions 181, 194, and 242), the UN has also described the Palestinian refugee situation as “by far the most protracted and largest of all refugee problems in the world today.”7

In 2012, a UN report predicted that Gaza could be rendered completely uninhabitable by 2020.8 This bizarre prediction is consistent with the notorious Zionist image of Palestine as “a land without a people”9 This image has now morphed into one in which a piece of that land has become unfit for human habitation, when its inhabitants number far more than they have at any other point in its history. Perhaps this uncomfortable contradiction epitomizes the core of what should be said about the recent history of Gaza in explaining the current Kafkaesque predicament of its civilian population. Undoubtedly, Mahmoud Darwish would have relished its poignant irony.

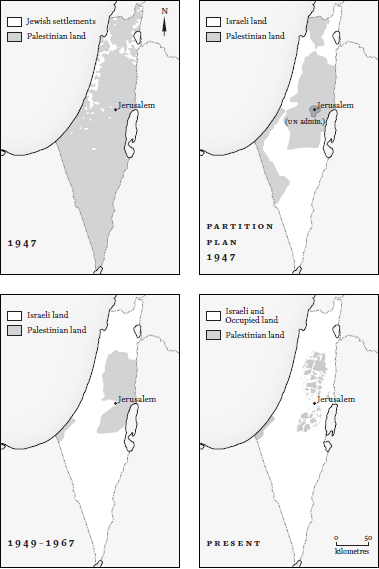

The loss of Palestinian land from 1947 to present.

Gazan life in the early half of the twentieth century was largely agrarian and market based for its eighty thousand inhabitants living in four small towns: Gaza, Deir Al Balah, Khan Younis, and Rafah.10 Even the most urbane of the Strip’s original inhabitants professed a deep connection to the homeland, and the most harried and overextended of Gaza’s lawyers and doctors made time to nurture fig trees or raise chickens. However, the situation changed dramatically with the 1948 Nakba when over two hundred thousand refugees arrived on the tiny strip of land,11 after simply traveling down the road without crossing even a single international border, looking for safe haven. Many of them imagined a sojourn in the Strip, probably for a “few days or weeks.”12 Establishment, in 1949, of the United Nations Relief Works Agency for Palestinian Refugees (UNRWA) to provide vital services such as education, health care, and social assistance seemed to consolidate the status of these displaced persons, despite their abiding hope for “return.” Those who attempted to materialize that hope were forcibly prevented from returning and sometimes killed by Israeli forces. According to Israeli historian Benny Morris, in the period between 1949 and 1956, Israel killed between 2,700 and 5,000 people trying to cross the imaginary line back to their homes.13 Over time, the tent camps turned into concrete cities, where the politics of resistance incubated that would later flourish.

Egypt controlled the Gaza Strip until 1967. During the Suez Crisis of 1956, Israel occupied the Strip temporarily and committed massacres in Khan Younis and Rafah before Israel’s military was forced to withdraw. In Khan Younis alone, Ihsan Al-Agha, a local university teacher, documented the names of hundreds of people killed.14 This period was signified by the rise of the Fedayeen movement—a national movement of Palestinian resistance fighters who attempted to mount attacks against the state of Israel, which had occupied and destroyed their homeland. In order to deter Palestinians, Israel constantly attacked and bombarded Gaza. In August 1953, the Israeli commando force known as Unit 101, under the command of Ariel Sharon, attacked the Bureij refugee camp, east of Gaza City, killing over forty people. Two years later, in 1955, the Khan Younis police station was blown up, leaving seventy-four policemen dead.15 This period also witnessed tensions between the Egyptians and Palestinians against the backdrop of the Johnson peace proposal in 1955. Endorsed by the UN and the Egyptian government, the proposal sought to re-settle Gazan refugees in the northwest of the Sinai Peninsula. Popular demonstrations protesting the plan were directed against both the UNRWA and the Egyptian administration in Gaza.16 This wave of focused activism was the context in which the seeds of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) were sown.

The war of 1967, known colloquially as the Six-Day War, left the Gaza Strip and the West Bank occupied by Israel, as well as the Syrian Golan Heights and the Egyptian Sinai Peninsula. Soon after the war, Israel enacted the annexation of East Jerusalem. These developments generated a new set of legal and political structures that extend to the present day. In East Jerusalem, Israeli law applies to all citizens (whether Palestinian or Jewish). However, the Palestinian residents of East Jerusalem are required to hold special ID documents and they are not entitled to Israeli citizenship (unlike the Palestinian Arab citizens of other areas inside Israel, such as Nazareth). In the West Bank and Gaza Strip, the “occupied territories,” Israeli military law was applied. When Jewish settlements were introduced (that is, colonial townships for Jewish people planted on occupied Palestinian land), a new legal strand emerged and standard Israeli law was selectively and exclusively applied to the Jewish residents of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. Such were the emerging features of a regime that has gained increasingly unfavourable comparisons to apartheid rule in South Africa. In Israel and the territories under its control, legal restrictions on people are conditional upon identities and the respective status of these identities within heavily stratified and discriminatory laws. The regime, in other words, implements a “legally sanctioned separation based on discrimination.”17

The so-called “Six-Day War” of 1967 resulted in the expulsion of another 300,000 Palestinians from their homes, including 130,000 who were displaced for a second time after their initial displacement in 1948.18 The defeat followed by the military occupation shattered Palestinians’ hopes for return, but energized the national movements led by the Fedayeen. To pacify resistance in the Strip, then Israeli Defence Minister Sharon initiated a policy of home demolitions that continues to this day. As people in Gaza were subjected to intensified restrictions on freedom of movement and to increasingly squalid economic conditions, it was no accident that the 1987 Intifada was first triggered in Gaza, specifically in the Jabalia refugee camp, and rapidly spread across the remainder of the Strip before it was joined by the West Bank. The uprising was a mass popular movement that held up for six years. It manifested in protests and strikes, in civil disobedience, and in boycotts. Unable to supress the masses, Israel shut down Gaza’s universities for six years, denying tens of thousands of students the opportunity to study, including one of the editors of this series. It imposed curfews locking the entire Palestinian population of Gaza inside their homes every night for about six years.19 An order ascribed to Israel’s then Defence Minister, Yitzhak Rabin, directed the Israeli army to break the bones of Palestinian protesters.20 The images of unarmed Palestinian youths throwing rocks at fully armed Israeli troops captured attention in international media and contributed to a narrative of the Palestinian David fighting Israel’s Goliath.

Amidst the heat of the Intifada, a peace process was launched in Madrid under the auspices of the Americans and the Soviets in 1991. The process eventually culminated with the Oslo Accords, signed by Israel and the PLO on the White House lawn in September 1993. In keeping with the terms of the Accords, the Palestinian Authority (PA), an interim self-governing body, was constituted. The PA, led by the late Yasser Arafat, along with the PLO leadership, were allowed to return to Gaza and establish a headquarters. Oslo was the pinnacle of Palestinian hopes for statehood and self-determination. Widespread discussions stated that Gaza would become the “Singapore of the Middle East.”21 These hopes evaporated, however, when the Accords panned out as the “biggest hoax of the century.”22 They neglected to deal with the core issues of both the conflict and the Palestinian cause: with the Palestinian refugees, with the right of their return, and with the 1948 Nakba.23 Reflecting his deep frustration at the aftermath of the Oslo Accords, Palestinian historian Salman Abu Sitta, himself a refugee expelled to Gaza along with his family, wrote to PLO leader Yasser Arafat, asking him why the Accords and his ensuing speech at the UN had omitted “Palestine,” “Palestinians,” and demands for inalienable rights:

I wished to hear you, Mr. President, say in your speech: I stand before you today to remind you that forty-six years ago 85 percent of my people were uprooted by the force of arms and the horror of massacres, from their ancestral homes. My people were dispersed to the four corners of the earth. Yet we did not forget our homeland for one minute…Let us learn the lesson of history: Injustice will not last. Justice must be done.24

“Oslo,” as the Accords are commonly called, entrenched the segregation of Palestinian communities. In 1994, a fence was erected around Gaza; a permit system was applied to anyone who needed to leave the Strip. This had a drastic impact on the population’s ability to conduct anything approximating a “normal” life, while severely weakening the Strip’s economy.

The failure of Oslo to recognize the core issues at stake for the Palestinian people was followed by the breakdown of negotiations between the PA and Israel in late 2000. This stalemate provided fertile ground for the eruption of the second Intifada. Israel’s violence in suppressing this uprising unleashed the full might of the world’s fifth largest army against a defenceless civilian population. Daily bombings by F-16 fighter jets became the soundtrack of daily life in Gaza, while Palestinians mounted armed attacks against Israeli military posts inside the Strip and against the army and sometimes civilians in Israeli towns and cities.

In 2001, Sharon declared war on the PA’s leadership, security officials, and infrastructure. Israeli bulldozers destroyed the runway of Gaza International Airport, attacked the symbols of Arafat’s authority, and bombarded and destroyed Arafat helicopters. These attacks left much of Gaza’s internationally funded infrastructure in ruins.25 Even worse, however, as a form of collective punishment of Gazans, Israel imposed a policy of internal “closure,” preventing movement within the tiny Strip. It divided the Gaza Strip into three parts. The principal closure points were on the coastal road to the west of the Netzarim colony (formerly located between Gaza City and the Nuseirat camp) and at the Abu Holi Checkpoint (named after the farmer whose land was confiscated to build the checkpoint), located at the centre of the Strip. Each time the Israeli army shut down these points, Gaza was split apart, paralyzing all movement of people and goods.26 For five consecutive years, for Gazan doctors, nurses, patients, students, teachers, farmers, labourers, and mothers, a trip from north to south—ordinarily a ninety-minute round trip—could turn into a week-long ordeal, and dependence on the kindness of one’s extended family for accommodations and food until the checkpoints were re-opened.27

In 2004, Dov Weisglass, advisor to Prime Minister Sharon, declared his strategy of rendering the peace process moribund and his intention to sink it, along with Palestinians’ national dreams, in “formaldehyde.”28

Israeli political activity has always been rooted in unilateralism. The false narrative of a “land without people” permitted the “people without a land”—now instated in what was formerly Palestine—to conduct themselves in absolute disregard of the existence of another people. The latter, like so many rocks and boulders, were simply to be bulldozed flat as the new state was being constructed. Israel’s unilateral disengagement from Gaza in 2005, vacating about eight thousand settlers, whose houses and farms covered forty percent of the area of the Strip, was an act of political sleight of hand that allowed Israel to declare itself free of political and moral responsibility for the Gaza Strip, while also declaring it an “enemy entity”29 in 2007. It could accordingly be enveloped in a siege designed to generate medieval living conditions.30

The 2006 free and fair elections that brought the Islamic resistance movement, Hamas, into power were the fruit created by Israel’s departure, viewed by many Palestinians as a victory of the resistance, led by Hamas, to Israel’s brutal policies of oppression, as well as to the inherent weakness at the heart of the Palestinian Authority. The latter, which is supposedly authorized to govern, is constrained by severe limitations that effectively disable the centrifugal forces allowing the governance of states. The US and the EU were the parties at whose demand the fledgling Palestinian Authority conducted elections, and these were declared fair and free by all international monitors. And yet, these same parties proceeded to boycott the results (which they found unsatisfactory) and to cut foreign aid to the PA. For the most part, these cuts and the shortages they incurred were imposed upon Gaza (and to a lesser degree, the West Bank).

Declaring Gaza an “enemy entity” allowed Israel to conduct three major offensives against the Strip, in 2008, 2012, and 2014. The 2014 offensive , which lasted 51 days, destroyed much of what had previously functioned as Gaza’s infrastructure and institutions, including the complete or partial destruction of at least 100,000 homes, 62 hospitals, 278 mosques, and 220 schools.31 It also left 2,300 people dead, the majority of these being civilians, and tens of thousands wounded.32

Four generations of refugees now live in the Gaza Strip, scattered among eight refugee camps. As of 2020, Gaza is still under siege. Access to the outside world is controlled by Israel, or by Egypt, acting as Israel’s sub-contractor. No one can enter or leave the Strip without permits from one of these two powers. According to Oxfam, in 2019, one million Palestinians in Gaza lacked sufficient food for their families. Sixty percent of these Gazans were subsisting on less than $2 a day. Unemployment, measured at 62 percent in 2019, is among the highest in the world.33 Economist Sara Roy has characterized the pattern as one of structural de-development,34 and Israeli historian Avi Shlaim describes it as “a uniquely cruel case of intentional de-development” and a “classic case of colonial exploitation in the post-colonial era.”35 Although the World Bank has said that Gaza’s economy is in “free fall,”36 the Strip has in fact maintained a perverse stasis: formaldehyde, after all, is used to preserve corpses.

Israeli sociologist Eva Illouz recently compared the present circumstances of the Palestinian people to conditions of slavery. These conditions, she said, present one of the great moral questions of our time and are similar, in certain respects, to the slavery that embroiled the US in civil war in the nineteenth century.37

The strands of oppression and violence running through the Palestinian tapestry are interwoven with strands of endurance, ability to overcome, and Sumud—steadfastness—in the face of injustice. Palestinians still firmly believe in return and in the possibility of justice, even if these ideals have become embattled and tattered. Gaza’s high level of concentration on the importance of these narratives belies its tiny size, at just 1.3 percent of historic Palestine. Protesting the circumstances of all Palestinians, the near suffocation of the Gaza Strip, and the international disinterest in both, Gazan civil society launched the Great March of Return in 2018. Weekly protests were initiated along the border fence with Israel every Friday, calling on both Israel and the world to recognize the inalienable right of Palestinians to return to the homes and lands from which they were forcibly removed seven decades ago. The protestors also insist upon a plethora of other basic rights denied to Palestinian people in the “ongoing Nakba” of their lives.38 The World Health Organization reported over 300 Gazans were shot and killed by the Israeli army in the course of these rallies, as of December 2019, with 35,000 more injured.39 On May 14, 2019 alone, Israeli military snipers killed 60 unarmed demonstrators and wounded 2,700.40

The weekly marches are an ongoing journey fulfilling the prophesy of Mahmoud Darwish that “a stone from our land builds the ceiling of our sky.”41 Every independent state formed after “the dismantling of the classical empires in the post-World War Two years” has recognized an urgent need “to narrate its own history, as much as possible free of the biases and misrepresentations of that history,” as written by colonial historians.42 In an analogy to the poetry that represents a highly important oral tradition in the Arab world, we see this book as an effort to capture the poetry of life and the history of a people, expressed by those who live it on a daily basis.

Filling in a Tapestry of Resistance Through Memory Work

The history of Gaza is far richer and deeper than the standard narratives of helplessness, humanitarian disaster, or war story would have us believe. Moreover, as is the case with other post-colonial regions and their histories, Gazan history differs greatly from official accounts and Eurocentric renderings based (largely) on oversimplifications.43 This series is, accordingly, an attempt to replace detached—and sometimes questionable—statistics and chronologies of erupting conflict with some of the concrete details of actual survival and resistance, complex human emotions, and specific difficult choices. The stories recounted reflect crucial facts and important events through the evidence of lived experience. They contextualize selective reports and statistics, correcting omissions, misrepresentations, and misinterpretations.

This series is an attempt to re-imagine the history of Gaza from the viewpoint of its people. A true understanding of Gaza entails a reading of the human history beyond and behind chronologies, a reading that follows some of the coloured threads that make its tapestry so vibrant. The seven women whose stories we relate communicate the history they lived, through reflecting on events they experienced in their own voices and vocabularies. They shared feelings and named processes as they understood them, enabling others to grasp and realize the sheer dimensions of the injustice to which they were subjected and which they amazingly withstood.

Israeli New Historian Ilan Pappe has used the term “memoricide” to denote the attempted annihilation of memory, particularly that of the Palestinian Nakba. A systematic “erasure of the history of one people in order to write that of another people’s over it” has constituted the continuous imposition of a Zionist layer and of nationalized Israeli patterns over everything Palestinian.44 This has included the erasure of all traces of the Palestinian people—of the recultivation and renaming of Palestinian sites and villages. These practices were recounted victoriously by Moshe Dayan in 1969:

We came to this country which was already populated by Arabs and we are establishing a Hebrew, that is, a Jewish state here. Jewish villages were built in the places of Arab villages and I do not know even the names of these Arab villages, and I do not blame you, because the geography books no longer exist, the Arab villages are not there either. Nahalal arose in the place of Mahlul, Kibbutz Gvat in the place of Jibta; Kibbutz Sarid in the place of Huneidi and Kfar Yehushua in the place of Tal al Shuman. There is not a single place built in this country that did not have a former Arab population.45

In the context of daily hardship, then, memory is crucial. It is a deeply significant site for resisting policies of elimination and erasure. Often, such resistance work takes place within families, and, in particular, through women. Stories of lost homes are handed down from generation to generation and repeated time and again, preserving the names of lost villages and towns, detailing former landholdings, passing on deeds, and recounting traditions and tales about “the ancestors, everyday life, the harvests, and even quarrels.”46 When asked where they are from, most of the children of Palestinian refugee families will state the name of a village lost generations ago.

In recognizing women’s diverse experiences as a key to decoding history, we share accounts of women of the generation that experienced the 1948 Nakba, told with the backdrop of the master narratives of Gaza, offering new insights into the story of Palestine. The respective narrators enable readers to gain a fuller understanding of the scale of tragedy experienced by each of these women and of its socio-economic and political impacts.

The series draws on the concept of “History from Below” proposed by the French historian Georges Lefebvre, who emphasized that history is shaped by ordinary people over extended periods of time.47 It also draws on the feminist concept of “Herstory,” where feminist historians and activists reclaim and retell the suppressed accounts of historical periods as women, particularly marginalized women, experienced them. It is in these traditions that we present the oral histories of Palestinian women from the Gaza Strip. The school of oral history, initiated with tape recorders in the 1940s, achieved increased recognition during the 1960s, and is now considered a major component of historical research that enlists the assistance of twenty-first-century digital technologies.48 In defending the method of recording oral history, Paul Thompson argued, in The Voice of the Past: Oral History, that it transmutes the content of history “by shifting the focus and opening new areas of inquiry, by challenging some of the assumptions and accepting judgment of historians, by bringing recognition to substantial groups of people who had been ignored.”49 The historically “silent” social groups cited by Thompson include Indigenous people, refugees, migrants, colonized peoples, those of subaltern categories, and minorities. Such groups have employed the methodology of oral history to counteract dominant discourses that suppress their versions of history. Alistair Thomson argued that “for many oral historians, recording experiences which have been ignored in history and involving people in exploring and making their own histories, continue to be primary justifications for the use of oral history.”50 In efforts to represent the totality of truths, oral history has been recognized as a method of realizing the rights of marginalized people to own and sound a voice, to share and reflect on their collective experiences, and to resist the dominant colonial rhetoric that omits or obliterates these experiences. In this context, Julia Chaitin argues that oral history is not simply an attempt to find an alternative historical text, but also to gather new information that cannot be located by other means as it is undocumented.51

Oral history, as a method that both enhances and disrupts formal history, has not yet taken root extensively in the Arab world. Among a few rare exceptions, according to anthropologist and historian Rosemary Sayigh, are the Palestinians “who have used oral and visual documents to record experiences of colonialist dispossession and violence that challenge dominant Zionist and Western versions of their history.”52 In gradually moving “from the margins to the center,” this practice has come to constitute the core of Palestinian historiography in the past twenty years,53 and is deployed abundantly, both formally and informally, in collecting and reviving knowledge that was formerly unrecorded. In response to Edward Said’s call for the “permission to narrate,” oral history has paved the way for the continued production of archival collections, resisting the ongoing erasure of Palestinian spaces, existence, history, and identity. Sherna Gluck notes that this method not only recovers and preserves the past through the collection of accounts, for example, of the Nakba, but also establishes the legitimacy of claim and of the right of return.54 For Palestinians such as Malaka Shwaikh, a Gaza-born scholar, oral history and memory of the past act “as a force in maintaining and reproducing their rights as the sole owners of Palestine” and as “fuel for their survival.”55

Over the past two decades, numerous laypeople, non-governmental organizations, and solidarity workers have joined the intellectual mission of rescuing a history that aims, according Said, to advance human freedom, rights, and knowledge.56 That mission has gathered momentum and gained significance in historic Palestine in a context of neglect on the part of the Palestinian national leadership, which has failed to organize and ensure continuous records or documentation of popular Palestinian experience and of the ongoing dangers posed by the Israeli occupation.57 The specifics of this violence as a current historical process were highlighted in a book by Nahla Abdo and Nur Masalha titled An Oral History of the Palestinian Nakba (2018). The book includes a detailed discussion of the potential of oral history for historicizing marginal experience. It also notes that Palestinian history has not been adequately recorded as the experience of both a community and of individuals and emphasizes the vital role that oral history plays in assembling the Palestinian narrative.

The role of Palestine during World War II features prominently in standard historiographies, but little has been written about its Indigenous population, the conditions of their existence prior to 1948, or their collective life and history before exile. Summing up this gaping void, Said wrote: “Unlike other people who suffered from a colonial experience, the Palestinians…have been excluded; denied the right to have a history of their own…When you continually hear people say: ‘Well, who are you anyway?’ you have to keep asserting the fact that you do have a history, however uninteresting it may appear to the very sophisticated world.”58

Scholarly Work on Palestine’s History

Many historians and researchers have drawn on both oral and visual history to counter the multi-form suppression and abandonment—ranging from disinterest to fundamental denial—of Palestinian history recounted from Palestinian standpoints. A variety of strategies have been adopted in carrying out such work, and famous among these efforts is Walid Khalidi’s Before Their Diaspora: A Photographic History of the Palestinians, 1876–1948 (1984). Others have presented individualized narratives, for example, in Salman Abu Sitta’s Mapping My Return: A Palestinian Memoir (2016), Ghada Karmi’s In Search of Fatima: A Palestinian Story (2009), and Leila El-Haddad’s Gaza Mom: Palestine, Politics, Parenting, and Everything In Between (2010). Scholars such as Ramzy Baroud, in Searching Jenin: Eyewitness Accounts of the Israeli Invasion 2002 (2003), have used oral testimonies in more comprehensive works to gain a fuller understanding of specific events (in this case, Israel’s siege on Jenin in 2002), while linking the event in question to collective Palestinian history. Others have recounted the singular history of specific political factions, for instance, Khaled Hroub in Hamas: Political Thought and Practice (2000) and Bassam Abu Sharif in Arafat and the Dream of Palestine: An Insider’s Account (2009). Several online projects and websites, such as Palestine Remembered, have also initiated and continue to maintain an ongoing collection and dissemination of Palestinian oral histories.59

Nakba: Palestine, 1948, and the Claims of Memory (2007), edited by Ahmad H. Sa’di and Lila Abu-Lughod, is one of the more prominent attempts to incorporate oral history as an essential means of delivering history, justice, and legitimacy for the Palestinian cause, while also linking current events to the recent past. Departing from the Nakba as a central event that defines and unites Palestinians, their volume undertakes the injection of collective memory into the overall framework of Palestinian history. Making memory public, Sa’di and Abu-Lughod write, “affirms identity, tames traumas and asserts Palestinian political and moral claims to justice, redress and the right of return.”60 It also challenges the Zionist myth that Palestinians have no roots in the land.

Some authors have taken up Said’s idea of the intellectual’s mission being to advance human freedom and knowledge.61 This idea is based on Said’s definition of the intellectual as being both detached and involved—outside of society and its institutions, and simultaneously a member of society who is constantly agitating against the status quo. Ramzy Baroud’s book My Father Was a Freedom Fighter: Gaza’s Untold Story (2010), the Indigenous section in Ghada Ageel’s edited volume Apartheid in Palestine: Hard Laws and Harder Experiences (2016), which includes chapters by Reem Skeik, Samar El Bekai, and Ramzy Baroud, and Palestinian poet Mourid Barghouti’s I Was Born There, I Was Born Here (2012) are all manifestations of a concept in which the outsider is also the insider, the researcher, and the narrator. The authors of these narratives either spent a large part of their lives under Israel’s occupation or returned from exile and experienced the suffering of both the individual and the group. These experiences generated their common aspiration to become intellectuals who would repeatedly disturb and problematize the status quo. In documenting their personal stories and describing everyday life in the West Bank and Gaza, these insider-outsider-researcher-narrators have attempted to link present and past.

Within the broader context of abandoned and suppressed narratives, accounts of women’s experiences, elided almost completely from hegemonic histories, open sorely neglected but significant avenues into an understanding of how the past and the present are constituted, reconstituted, and conceived. Women’s accounts are particularly vital for comprehending the past and present in Palestine, as they are framed and determined by the ethnic cleansing of 1948. While women’s stories are largely marginalized, their experiences form a cornerstone of the structure of human impacts generated by successive military campaigns against Palestinians and by generations of Palestinian resistance, both military and non-violent. Foregrounding women’s narratives counteracts a history in which selectiveness reinforces and supports systems of oppression and displacement through the erasure of authentic voices and the prioritization of male dominant narratives.

The tragedy of 1948 and its aftermath in Palestine have been endured by the whole of society and particularly by women, who have borne the remnants with which to reconstruct lost homes both on their backs and in their hearts. As they have put up and organized tents to house their families, they have cared for and raised children, and queued for hours to receive United Nations rations and handouts of clothes, blankets, and kitchen utensils. They have struggled to keep smiles on their own faces and those of their families in the face of humiliation and bitter pain, in the day to day practice of what Palestinians call Sumud. Uncovering the details of their life journeys under such exceptional circumstances reveals a version of Palestinian history that is not only far more complete, but that also acknowledges the central role that women have played in making this history. Sayigh has argued that

women have been a basic element in the Palestinian capacity to survive poverty, oppression, exile. They have been models of courage, tenacity, resourcefulness and humour. Though all were victims of expulsion and of gender subalternity, I would never think of them primarily in these terms, but rather as people who knew/know how to live against poverty and oppression. Palestinian women have the inner resources to make a good life for their children. They pack, and move, and set up again in a new place, among new people.62

Research on the role of gender in preserving the memory of the Nakba has been carried out by several scholars who have attempted to detail and highlight this crucial agency. In their contribution to Nakba, edited by Sa’di and Abu Lughod, Isabelle Humphries and Laleh Khalili used oral history to “examine both how the Nakba is remembered by women, and what women remember about it.”63 It was also crucial to them to investigate how women’s memories “were imbricated by both the nationalist discourse and the same patriarchal values and practices that also shape men’s lives and their memories.”64 Their chapter confronts the manifold predominant narrative and the resulting lack of confidence that has suppressed women’s voices and constrained their role as a conduit of memory.65 Palestinian women’s lack of self-confidence vis-a-vis, and exacerbated by, the male-dominant narrative is clearly reflected, for instance, in Sayigh’s quotation from one narrator: “I can’t say I know all this history; others know it better.” While this narrator is an “eloquent history teller” who is familiar with the events she witnessed, she still designates the task for telling history to those “who would know better.”66

Fatma Kassem’s book, Palestinian Women: Narrative Histories and Gender Memory (2011), focuses on Palestinian women living in Israel. Kassem collected the oral testimonies of twenty urban Palestinian women, a group whose life stories of displacement are rarely noted, even though they form essential parts of the larger Palestinian national narrative. Kassem, who was born in today’s Israel years after the Nakba, positions herself as both an insider—a narrator of her own story—and an outsider—a researcher—in the volume that aims to reveal “the complex intersections of gender, history, memory, nationalism and citizenship in a situation of ongoing colonization and violent conflict between Palestinians and the Zionist State of Israel.”67 Like Baroud, Ageel, and Barghouti, this positionality allowed her a great deal of freedom in crossing boundaries as an unconstrained outsider while interacting intensively as a trusted insider with the other narrators, whose stories, she said, “shaped” her life “as much as [they] did theirs.”68

The work of Sayigh exhibits a similar type of direct interaction with the narratives of Palestinian women. She has authored several books examining the oral history of the Palestinians, notably, The Palestinians: From Peasants to Revolutionaries.69 In her work, Voices: Palestinian Women Narrate Displacement, an online book, Sayigh narrates the stories of seventy Palestinian women from various locations in the West Bank, the Gaza Strip, and Jerusalem.70 The interviewees spoke about their lives following the displacement of Palestinians after the Nakba. Like most of her influential work, Sayigh’s interviews—conducted between 1998 and 2000, just prior to the initiation of this project—investigate displacement and its effects on Palestinian women, and the impact of the Nakba on the identity of women and their sense of self. Also considered in her book is the linkage between collective displacement and the critical role played by women in the Palestinian narrative. Sayigh’s body of work has not only advanced the destabilization of dominant narratives, making space for a more egalitarian narration of history, it also accurately situates Palestinian women at the centre of Palestinian history, offering a fuller, more representative understanding of Palestinian history altogether.

The Women’s Voices from Gaza series is a continuation of the oral history work carried out by many intellectuals and individuals who aimed to assign Indigenous Palestinians a greater role in explaining the dynamics of their own history and to re-orient the story of Palestine by restoring it to its original narrator: the Palestinians. It is a complement to a corpus of work that preceded this series and that asserts the centrality of the narrative of Palestinians, especially women, in reclaiming and contextualizing their history.

A White Lie

The first narrative in our series turns the clock back ninety years and invites readers on a journey of reimagining a once-upon-a-time in Palestine. The story recounts a life of happiness, uncertainty, loss, and also, ultimately, of pride, resistance, and hope. Weaving together many narrative threads, A White Lie unearths a version of history long excluded from mainstream discourse, illuminating a vibrant culture, rich community relations, old traditions, and grand resistance. It is the story of Madeeha Hafez Albatta, a woman with the warmth and depth of the homeland. Madeeha was born and raised in Khan Younis, a town in the southern part of the Gaza Strip, and her life took her, along with her family, across mandatory Palestine to Egypt, Jordan, Syria, Lebanon, Tunis, the United States, Germany, Greece, Austria, and Canada. In 1938, with Palestine under the British Mandate, Madeeha had to resort to tricking her family into allowing her to attend college. That trick changed her life forever. She became a teacher while still in her teens and then the headmistress of a school while in her early twenties, the youngest headmistress in Gazan history and most likely in the entire region.

As a teacher and headmistress, a campaigner for rights, an activist and community organizer, a mother, and a champion of dignity, Madeeha witnessed some of the most turbulent periods of Palestine’s recent history. Widely viewed as a symbol of love and freedom, she advocated an honourable life in all these roles. Her life story presents a model of bravery and strength, demonstrating the collective Palestinian will to stand fast and resist the odds. She was among the pioneers to rally her community to guarantee the right to education for thousands of children arriving in Gaza after the destruction of their homes and homeland in 1948. Upon witnessing the influx of hapless refugees, Madeeha immediately began mobilizing community efforts and energies to secure schooling before the arrival of any outside assistance, including that of the UNRWA (United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East). She was the driving force and key organizer behind the refugee schools, which were set up without aid from any international organizations. Madeeha saw education as a crucial means of survival and a way to preserve Palestinian traditions, culture, history, and identity. Building on this vision and mission and on the nucleus she had set up, the UNRWA then took responsibility for the education of refugee children.

In 1956, Madeeha lost both of her brothers, Hassan and Nadid, who were slaughtered by Israeli soldiers together with hundreds of civilian men and youth in Khan Younis. She was forced into the uncertainty of exile, away from her children and unable to return to her home for almost six months, due to the military campaign waged by the UK, France, and Israel against Egypt, as well as the occupation of the Gaza Strip. Her shock and dismay at this tragedy and her sense of powerlessness and despair, magnified by distance and the inability to support and share with others, approximate the feelings of hundreds of thousands of Palestinians living in exile at the time who witnessed repeated attacks on beloved family members, friends, neighbours, and an entire nation. Madeeha lived on to witness Egypt’s defeat in 1967, followed by Israel’s military occupation of the remnants of Palestine, including the Gaza Strip, while her husband, Ibrahim Abu Sitta, was deported to Sinai along with other community leaders, forcing Madeeha to live through worry and enforced separation. In 1970, during a short visit to Amman, Madeeha experienced the purge of Palestinian leaders by Jordan’s regime, known by Palestinians as “Black September,” surviving yet another period of horror away from her family and home. The eruption of the first Intifada in 1987 revived Palestinians’ hope and spirit of resistance and culminated with the Oslo Accords in 1993 and 1995. The period of hope, which Madeeha shared, was short lived, however, ending in 2000 with the outbreak of the second Intifada that manifested the despair experienced by Palestinians. A White Lie reveals how these events shaped Madeeha’s life and the lives of her family members. It traces the unimaginable decisions and actions they were forced to take in order to safeguard the remains of Palestine, through educating and attempting to protect the family’s children, while also caring for extended family and leading the community.

But Madeeha’s story provides far more than the account of an individual life under continued and complex political upheaval and war. Her narrative preserves minute details of distinctly Palestinian individual and collective life through different eras and regimes. It depicts a vibrant culture, old traditions, customs, and other critical features of Palestinian society that readers rarely encounter. The narrative spans her childhood and early adulthood, including her train trips across Palestine and the Levant (Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, and Palestine), providing a picture of ordinary Palestinian family life in the early twentieth century. This period of the British Mandate in Palestine is largely neglected in other works, while those accounts that do exist invariably focus on the political clashes of the time, between Palestinians and the British and later Palestinians and the Zionists. Little mention is made of the rich tapestry of day-to-day life in Palestine.

Madeeha’s narrative also uncovers untold parts of the Palestinian story, as it captures the disruption and change in Palestine caused by the 1947 partition plan and the 1948 Nakba. Her uncovering of such changes has also been very clear in her literary writings, published in Al Risala and Al Thaqafa, two prestigious Cairo magazines, which according to Abu Sitta were the closest equivalent to today’s New York Times Review of Books.71 The experiences that surface in her tale highlight the role played by civil society in mitigating the national tragedy. Sounding her amazingly resilient voice, the narrative depicts Madeeha reaching out to Gazan civil society to seek help and reflects the immensely impressive response. Records of strong community relations, a healthy civil society, and women’s central roles in it are aspects that are largely absent from scholarship on Palestinians. The narrative further reveals the depth of the solidarity of Palestinians from Gaza with their brothers and sisters: the displaced peasants and city dwellers who found refuge in Gaza. Like the other narratives we share in this series, Madeeha’s story conveys the displacement and dispossession with great clarity. It speaks of a land and a people with a culture and history that existed before these events for generations, completely contradicting the infamous Zionist myth of Palestine as a land without a people unproblematically awaiting a people without a land.

Moreover, Madeeha’s lived experiences of childhood, adulthood, education, employment, activism, love, marriage, and aspirations draw an image that belies widespread western, orientalized stereotypes of Arab Muslim women. Her story portrays the capacities, strengths, and abilities of Palestinian women and reflects their aspirations and feelings, as well as their engagement with patriarchal social constraints in struggles for change that are analogous to those of women in many other areas throughout the world. It also reveals the racism embedded in common attempts to frame, and in fact misrepresent, the struggle of Palestinian women within their cultural tradition and religion. On top of their inaccuracies, such explanatory frameworks fail to capture the unending forms of violence that militarized occupation has practiced on women in Palestine.

Madeeha’s narrative was selected to be first in this series because her life experience and personality overlaps with, corresponds to, and unites all of the women represented (whether a native resident of Gaza, a refugee, a mother of prisoners, a villager, or an exiled returnee). To a large extent, her life journey corresponds to and communicates the collective Palestinian story. As a citizen from Gaza, Madeeha opened her arms and heart to arriving refugees who entered the Strip. In aiding and also, notably, listening to them, Madeeha could grasp the concrete meaning of losing one’s home and being forced to become a refugee in one’s own land. A year after the Nakba, she was married to one of these recent refugees, a lawyer from Al Ma’in who went on to become a magistrate, a national figure, and ultimately the first mayor of the city of Khan Younis under the Egyptian administration of the Gaza Strip. Together with Ibrahim, on a journey of over six decades, Madeeha managed to raise a family of nine despite formidable challenges and very complicated circumstances. Her chief concern was sheltering her children against the dangers and harm of military occupation and a settler colonial regime that practices apartheid. All this while Palestine—the cause and the people—remained the discernible, steadfast centre of their lives.

The battles that Madeeha waged continue. The children and grandchildren of her generation are now taking the lead and following the trail that she, like so many other Palestinians, blazed seventy-two years ago. It is this generation of refugees and non-refugees, men and women, and boys and girls who have marched for rights and dignity along the razor-wire fences that confine Gaza’s residents. Gazan civil society is presenting another model of its people’s strategies of mobilization and struggle for justice, which are at once traditional and innovative. Palestinians from all parts of society are participating in the Great March of Return, as a call to the world to recognize their inalienable right to return to the homes and lands from which they were forcibly removed seven decades ago. Gazans are also demanding an end to the notably immoral blockade that denies them freedom of movement, the right to education, the right to life, the right to livelihood, and the right to feed their children, as well as the rights to fish their waters, cultivate their land, export their products, and to drink clean water and receive medical treatment. These are the same very basic rights that Madeeha struggled to attain.

Madeeha paid heavy personal prices in order for her and her family to struggle for freedom. Today’s younger generations protesting at Gaza’s borders are also paying heavily for exercising the right to take part in determining their future, and for practicing an advanced form of participatory democracy to call world attention to their slow strangulation by blockade. In peaceful demonstrations and sit-ins, held in the buffer zone imposed by Israel hundreds of yards from the outer perimeter of the fence encaging Gaza, they have narrated and staged a legendary epic of resistance, celebrating the Palestinian survival, traditions, culture, and history that Madeeha worked so hard to preserve. As of the beginning of 2020, protesters have continued to gather every day for well over a year, since March 30, 2018, to sing, dance traditional dabkeh, share stories, fly kites, cook traditional meals, and recount memories of what once was their homeland, all while praying for and dreaming of return.72

Ignoring their message and disregarding their right to life, Israeli army snipers, stationed in jeeps and military towers behind multiple stretches of barbed wire, with no imminent threat to their lives, are systematically targeting demonstrators with live ammunition. In February 2019, after a year of demonstrations, an independent Commission of Inquiry, set up by the UN Human Rights Council, confirmed “reasonable grounds to believe that Israeli snipers shot at journalists, health workers, children and persons with disabilities, knowing they were clearly recognisable as such.”73 Accordingly, the report found that the Israeli army might be responsible for war crimes in Gaza against protestors involved in the Great March of Return.

Madeeha died a natural death in her home in Gaza on December 22, 2011, at the age of 87, leaving a legacy that has already become a beacon for the ongoing march of the Palestinian people toward freedom and dignity. A poem written by Maheeda seventy years ago still accurately portrays the current situation in occupied Palestine and in besieged Gaza. It summarizes the agony of Palestinians, their yearning for freedom, and their daily suffering under occupation, siege, and apartheid. It presents a Gaza that is not just a piece of land, but a place in which a history of resistance, resilience, and Sumud (steadfastness) has formed. The poem sends an open invitation to the world, urging it to engage with her struggle to save lives and achieve justice.

A BIRD AND OTHER BIRDS

You are lucky birds, flying from tree to tree, rose to rose.

You are happy birds, singing and dancing.

I can’t understand your songs and I can’t understand your laugh because I am imprisoned here.

Please come and see my tears, my situation, my life.

It’s an awful life. I wish to be like you, but I can’t.