5 / Occupation

IBRAHIM WAS MAYOR between 1958 and 1964, and it was a golden era for Khan Younis. He did many things for Khan Younis and found work for many people throughout the municipality, which was possible because the situation was very difficult. He built and fixed roads and dug four additional wells and built four reservoirs, so instead of having one, we had five reservoirs of sweet water that was not salty as before. The water even reached people living outside of Khan Younis, and the citizens were angry because those outside the municipality boundaries did not pay for water, but Ibrahim told them that he couldn’t deny water to people just because they lived outside the municipality. He also built the Unknown Soldier Square in front of Barquq Castle in Khan Younis, but Israeli soldiers destroyed it when they occupied the Gaza Strip in the 1967 war. It was rebuilt when the Palestinian National Authority (PNA) came.

Ibrahim was responsible for building Nasser Hospital, and on the opening day, the Egyptian administrative governor came with many Egyptian officials and important people from Khan Younis. Many gave speeches in which they thanked the governor, but after they finished, he said that the one to thank for building Nasser Hospital was Ibrahim Abu Sitta:

For a long time he has been telling me of the necessity of building a hospital in Khan Younis and I told him there was no possibility, but he kept pushing until he had convinced me. He told me that Gaza has two hospitals, the Baptist and Shifa, where we always send sick people but many die on the way because of the distance. So we need a hospital, especially for emergencies, for those thousands of people. The hospital will not only serve Khan Younis but all the southern area so it will decrease the pressure on the other two hospitals. He kept giving me all these reasons until I agreed to build the hospital, so all of us have to thank this man.

This was February 24, 1960, and I was in the last days of pregnancy. I was visiting my family and felt the baby would soon arrive, so I told them I felt sick and went home. When I gave birth, I never sent for my family to be with me. Usually when I felt the birth pains, I told them that I was tired or cold and wanted to sleep or rest at home, and not to come and visit me. And they believed me because they didn’t know the exact month I was due. After I had delivered, Ibrahim would tell them the news. This time I felt very strong pains in my back, which became so severe that I phoned the office of the railway station to send the midwife who lived next door. Unfortunately, the office was closed at night because the train only came once during the day. The pain was so strong that I was forced to send Salma to my parents’ home to ask them to fetch the midwife, and my two sisters went to her home, which was very far away. As I felt the baby coming, my sister-in-law arrived because she knew the midwife would be a long time and was afraid something bad might happen while I was alone. She found me already boiling water and preparing aniseed tea and the necessary things for the baby. She helped me to my bed, and a minute later the baby arrived. Ibrahim came at that moment and she congratulated him on the birth of his baby son, but he was surprised because he thought that only a midwife could deliver a baby. She asked him to bring the midwife and he also brought a doctor, who assured him that everything was fine and asked what he was going to call the baby. He suggested we call him Nasser after both the hospital and Gamal Abd Al Nasser, and we agreed.

After I was married, I participated in community activities. I was invited by schools to give speeches on special occasions such as Mother’s Day, Withdrawal Day, and other national occasions, and I used these opportunities to encourage and raise the political level of the young generation and remind them of our land and our right of return. I considered all the Khan Younis girls, including the teachers and headmistresses, as my daughters because I knew all of them. I had taught most of them and those I hadn’t taught were my colleagues, or they had taught me. I did this a lot, and in fact I’m not so good at housework and don’t have the patience for it. I was more interested in reading and writing, especially poetry. I also encouraged the teaching of illiterate people because the Islamic religion encourages people to learn and study. The first word in the Quran is “Read,” which is an invitation to learn. Many times, I taught women to read the Quran with its correct rules for reading and listened to them and corrected their mistakes. I still read the Quran every day and listen to it as well.

In 1961, I had eight children, and Ibrahim was representing the Palestinian Lawyers Syndicate together with Dr. Haidar Abd al-Shafi and Mr. Mounir al-Rayyis, mayor of Gaza. They travelled to America for three months to represent Palestinian refugees at the UN, so I attended a sewing course organized by the UNRWA for thirty refugee women and girls. Some of them were married and their husbands had fled during the war and couldn’t return. I was able to sew from my mind and from what I saw, but not from patterns, and I really wanted to learn the rules of sewing and take part in the course, which was held in a big hall in a girls’ school. So, I studied with the girls and women, all of whom were illiterate, and discovered that none of them could hold a pencil and needed my help when they wanted to make measurements. I became so sad, and was even sadder when the married women brought me the letters they had received from their husbands to read, and asked me to reply to them. I told them they should learn to read and write because I was sure they didn’t want anyone but themselves reading their husband’s letters. I said I would try to help them, and I went to the course supervisor and offered to teach the women and girls to read and write. I told her that I needed about six months for the course, and hopefully after that time they would be able to read and write themselves. All I needed to start was permission to use the place, a blackboard, and some chalk. The sewing class finished at 1:00 PM, so I could teach from 1:00 to 3:00 PM because my husband was overseas, and I had two housekeepers at home who could take care of the children.

She agreed, so I started to teach the women. I could feel their strong desire to learn. They always urged me to give them more and more, so I brought books from Lebanon meant for illiterate education to teach them with. After two months, they were reading small articles in the newspapers, and at the end of the course, they were each able to write letters to their husband. During the course, they couldn’t believe that one day they would read their husband’s letters and also answer them. I always pushed and encouraged them by saying,

You have minds and you are clever, and you have the will to learn. Your problems resulted because your families didn’t send you to school, so now is the time to correct that mistake and learn. I want you to keep reading and writing at the end of this course, and if you don’t have newspapers or magazines you have the Quran. Everyone has the Quran at home and if you continue reading from it you will not forget these skills.

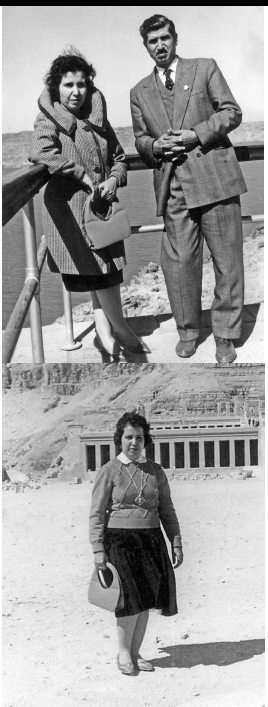

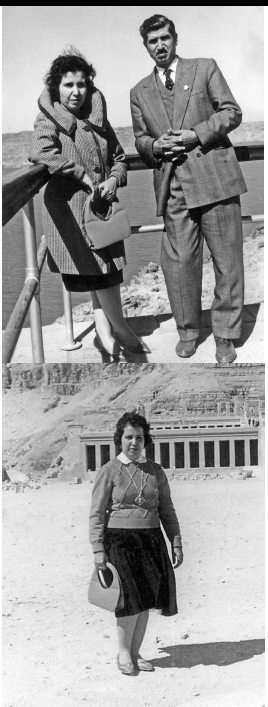

< Top: Madeeha Hafez Albatta with her husband Ibrahim Abu Sitta on their trip to Egypt for the conference in February 1961. The photo was taken at the construction site of the High Dam in Aswan. Photo courtesy of Madeeha’s family.

< Bottom: Madeeha Hafez Albatta on the trip to Egypt in February 1961. The photo was taken in Luxor at the Valley of the Kings (Wadi El Molouk) ancient site. Photo courtesy of Madeeha’s family.

In February 1961, a conference for Arab lawyers was held in Cairo. As well as being mayor of Khan Younis, Ibrahim was head of the lawyers’ syndicate, and he also had a legal office in Jerusalem. The lawyers took their wives to Cairo, and Abd Al Nasser invited the magistrates and the heads of the various lawyers’ associations to stay after the conference so he could entertain them with a trip to Luxor, which was very beautiful. There were forty-five of us and we visited Aswan and stayed in the best hotels, and Abd Al Nasser put a yacht at our disposal for a trip down the Nile. Then, after we returned to Cairo, he sent for us in the late afternoon. I asked the messenger if the wives were included but he didn’t know, so I told him that if the wives were not included in the invitation, they would not let their husbands go. The man returned and said that everybody was welcome, but not that day, the next day at the same time. I said that for sure Abd Al Nasser had postponed the meeting because he needed time to shave, do his hair, and iron his shirt!

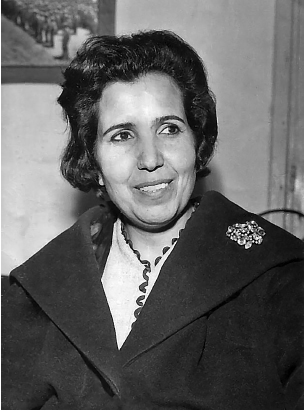

Photograph of Madeeha with Jamal Abd Al Nasser, Egyptian president from 1952–1970. Photo courtesy of Madeeha’s family.

The next day we met Abd Al Nasser in the centre of a big empty hall. It was the first time that I had met him in person, but this was not the case with Ibrahim, as he, as well as Abdallah, had led many delegations from Gaza to meet with Abd Al Nasser. People came through the front door and were greeted by him, and then passed by the guards behind him to go through another door, which opened onto a verandah and a garden beyond. Everyone said very polite and formal things when they met him, but when it was our turn to shake hands, I said to him, “I am from Khan Younis and on behalf of all Khan Younis people, particularly widows, orphans, and those with tragedies in their lives, I tell you that the blood of the martyrs and the people who were massacred is on your hands, and is your responsibility, from this day to judgement day.” Ibrahim tried to shut me up, but Abd Al Nasser’s eyes filled with tears, and he squeezed my hands and said, “If you are from Khan Younis, I can say I am from ’Iraq Suwaydan because I fought there, and I feel the Palestinian cause like you and more, and I am waiting for the day I can avenge all our martyrs, both Egyptian and Palestinian, and all those who were massacred.” It didn’t mean that he was Palestinian, he was Egyptian, but he had fought for Palestine, and ’Iraq Suwaydan was a village in the area of Al Majdal. And because he was under siege in Al Faluja for a long time before being forced to withdraw, he still wanted to seek revenge against the Israelis.

After Abd Al Nasser had finished welcoming everyone, he asked for a photo with the Palestinian delegation and the lady from Khan Younis, so Ibrahim and I climbed the steps and stood on either side of Nasser for the photo to be taken. Zuhair Al Rayess, the other member of the Palestinian delegation, was late in joining us and he came rushing up the stairs and barely lined himself up for the photo just before the photographer snapped the shot. He stood beside me, sensing that it might be too late to walk to the other side to stand next to Ibrahim as etiquette would require. When we returned to Khan Younis, Nasser sent the photo, and on the back was written, To Madam Ibrahim Abu Sitta from Jamal Abd Al Nasser. In the years that followed, we always had a laugh with Zuhair about his awkward posture when he visited us and saw the famous photo hanging on the wall of our guest room.

I have two surviving brothers: one is a teacher in Khan Younis, and the other a doctor in Libya. When my brother wanted to study medicine, my father sent Abd Al Nasser a telegram reminding him that he had promised to help families of martyrs and that his son wanted to study medicine, but he never replied. In December 1962, Ibrahim took Adala to Alhimiyat Hospital (which has now been demolished) in Gaza, where we discovered she had meningitis. No doctor in Khan Younis knew about this disease. She had a high fever and was vomiting, and she even vomited the medicine she was given. The next day, Ibrahim had intended to travel to Yemen as part of the Arab Lawyers Union, and early the next morning, while we waited for the driver to take him to the station to catch the train to Cairo, we heard a knock on the door and my sister-in-law’s voice. She told us that my father was very sick, so we went to see him. He told me, “You see Madeeha, Abd Al Nasser did not answer the telegram and did not keep his promise to help Ya’la.” I told him that I was sure he wanted to help, but maybe he didn’t have time. Then his condition became worse and Ibrahim fetched a doctor, who declared him dead.

In Muslim culture, we bury our deceased on the day of their death, and so Ibrahim sent his apologies and did not travel that day. It was a holiday in Gaza and Egypt, so all the government offices were closed and the mosques announced that my father had passed away. As it was a holiday, all of Khan Younis, the Egyptian administration, the Egyptian governor of Gaza, and judges attended his funeral at midday, after the second prayer. Ibrahim then traveled that night, taking a taxi for the five-hour journey to Cairo, 400 kilometres from Gaza, to meet his friends and fly to Yemen the next day. When he arrived in Egypt, he placed an obituary in the newspaper on behalf of the Khan Younis municipality, and Abd Al Nasser saw it and remembered the telegram. He sent us a telegram by the order of the Egyptian President to accept the student Ya’la Hafez Albatta at the medical college in Cairo as an exception, and he had dated it for the next day with his signature and stamp. We cried with happiness and wished my father could have been alive to see it.

My brother studied medicine in Egypt at the beginning of 1963, but he lost his residency right when the 1967 war started and couldn’t return to Khan Younis. So, he became displaced, along with about two hundred thousand Palestinians who happened to be outside Gaza and the West Bank when the war erupted. In 1971, he became engaged to his cousin and went to work in Saudi Arabia. Then he returned to Egypt, bought a house, and opened a clinic, and later went to Libya and is there still. He has visited a few times, but he is still displaced. He wants to come home and open a clinic and work so his children can live in their homeland, and hopefully he can return if the situation improves. We want to help him return because he has been in exile long enough. This is the problem of Palestinians: they are displaced, in exile. Everyone has their own problems, but in the end, it is the same problem. The same story, but with different characters.

At first, I thought it was my stepmother’s mistake that she did not apply for an identity card for my brother. I thought he might have received one then, if he had returned shortly after the war, but he didn’t. I did this with Adala and Hussein when we sent them to Kuwait one month after the 1967 war to study for tawjihi. We thought the occupation would only last for three or four months, and we were afraid they would lose the academic year. While they were in Kuwait, the Israelis conducted a census and they were not included, but when they returned, we applied, and they received their identity cards. But maybe my brother’s situation was different because he was away when the war took place, and it was impossible to get an identity card for him while he was gone. In fact, the whole purpose of doing the census right after the war was to deprive as many Palestinians as possible of their residence rights, by denying them identity cards. His mother, just as many other thousands of Palestinian mothers, could do nothing to challenge that policy and reunite her family.

The morning of the first anniversary of my father’s death, I prayed the first prayer and went back to bed, but I couldn’t sleep because I was remembering my father. Then I slept until about 9:00 AM, and while I was sleeping, I had a vision of my father lying on a mattress with an empty mattress beside him. A white jalabiya was on his mattress, and I picked it up to take it and told him that it wasn’t his because it was too small. But he told me to leave it because it belonged to his dear friend who would come to be with him today. I opened my eyes and wondered what it could have meant, and then I turned the radio to the Egyptian station, where I heard an obituary for a sheikh from Al Azhar University and then understood my father’s words. It was really strange that I dreamt that exactly one year after my father’s death, and it was correct.

After I had eight children, I tried natural birth control in which I avoided the fertile days. In 1963, I was sitting on the balcony looking at the sky and saw the moon and thought it was the beginning of the month, which meant it wasn’t a day I should avoid. When I looked at the date in the newspaper the next day, I found it was the middle and not the beginning of the month as I had thought, so I became worried, and the next month I found I was pregnant. I was unhappy at the beginning because I already had enough children and didn’t want more. But after I thought more about it, I believed that God wanted to give me another child and had made me confused about the date, so I accepted God’s will. In 1964, I had Azza, and after that I was very, very careful with dates and times.

Before we built this house in Gaza City in 1964, I gave Ibrahim one hundred and fifty [Egyptian] pounds I had saved from the housekeeping money, and I told him I wanted to build outside of Khan Younis on the land we had in Gaza, and he agreed. We moved here on September 9, 1965. Before, there were no buildings in front of this house, and because it was built on a hill, we had a view down to the sea. But, look now, the area is full of buildings.1

In 1964, the Egyptian administration employed five Palestinians from Gaza, and gave them five portfolios: health, education, civil affairs, land and properties, and law. Ibrahim was given the civil affairs portfolio, and for the first time Palestinians replaced Egyptians. Ibrahim was still going to his office in Jerusalem, and in order to reach it, he had to travel from Khan Younis to Cairo, to Amman, and then to the West Bank. He was also a member of the Palestinian Liberation Organization’s (PLO) executive committee when Ahmad Al Shuqairy was chairman. Ahmad Al Shuqairy was originally from Acre and represented Saudi Arabia at the United Nations. Then he started the PLO, and in 1964 became its chairman, and in time the Fatah movement became strong and took over the leadership.2 Al Shuqairy organized military training camps for Palestinians in the Gaza Strip, many areas of the West Bank, Syria, Jordan, and in many Arab countries. We used to celebrate his visits to Gaza, and when Ibrahim was mayor, he organized a reception and lunch for him at Khan Younis beach. He only stopped coming after the 1967 war. His last visit was on March 7, 1967, to celebrate Victory Day, the withdrawal of 1956, where he made a speech in Yarmouk Stadium in Gaza City and visited the Fedayeen training camps in the Gaza Strip.

Madeeha Hafez Albatta in Jerusalem in 1965. The photo was taken at a women’s conference in Jerusalem organized by the Palestine Liberation Organization (plo). Photo courtesy of Madeeha’s family.

In 1964, the Palestinian Women’s Union in Gaza was established, led by Yusra Al Barbari. I was a board member and responsible for literacy, so three days a week I trained teachers in teaching methodology and how to deal with children’s problems, especially in young children. Then, in 1965, the PLO organized a women’s conference in Jerusalem, and I was among sixteen women from Gaza, eighty from the West Bank, and many others from various Arab countries who attended. We travelled from Gaza to Cairo by train, then to Amman by plane. At that conference, I was elected along with three others to represent the women of the Gaza Strip through the women’s union. During the conference, it was arranged for us to meet King Hussein in Amman, but for some reason he cancelled the meeting. The organizers suggested that we visit Al Shuqairy’s Palestinian military group instead, where we had lunch and I gave a speech about the importance of their role in helping the Palestinian cause. When we returned to Gaza, the women’s union met in the PLO office on ’Omar Al Mukhtar Street, but it was closed after the 1967 war.

I used to visit the UN schools and other schools to speak to the girls, trying to promote and raise awareness of the Palestinian cause and the role of women in helping with the situation, and to give hope that one day we would have our own state and our rights would be returned and we would return to our land. Sure, we would suffer, but this would end if we were united. We also organized meetings for women and students in the Al-Jala’ Cinema, monitored by officials from the Egyptian administration to ensure that we didn’t use the space for other purposes or go against their policies.

Ibrahim was a member of the PLO executive committee from 1964 until around the end of 1966 or beginning of 1967, and had been given a leave of absence as the director of civil affairs to work full time as the head of the PLO popular resistance committees. In January 1967, at a meeting in Cairo with Al Shuqairy and other PLO members, he asked for permission to organize young men for military training, to use their energy instead of them sitting in the streets doing nothing. He wanted to do this rather than asking for help from Egypt, Jordan, or other Arab countries because he believed that only Palestinians could fight to have their rights returned. They disagreed, so he resigned and returned to his work with the Egyptian civil administration. This was fortunate for us because when the Israeli army occupied the Gaza Strip in 1967, he had already left the PLO and had nothing to do with them. If he had still been connected with the PLO, the Israelis would surely have killed, jailed, or deported him.

In 1967, the Israelis occupied the Gaza Strip, and the first thing they did was open the Allenby Bridge without restrictions so that Palestinians could leave but not return. They didn’t issue identity cards3 for people then, so they wanted as many people as possible to leave. Ibrahim’s former deputy in the PLO advised him to leave with him before they were arrested because they had both been members of the PLO, but Ibrahim refused. He told him that he would never leave his home whatever happened, because if he went, he would never be permitted to return. Also, if he left, many people would follow him, but Ibrahim thought that they should stay on their land and encourage people not to leave, whatever Israel did. This man was very afraid. As many Palestinians who were involved in PLO activities did, he left for Egypt, but Ibrahim stayed.

On June 5, 1967, as his driver waited to take Ibrahim to work, I saw from the balcony an Israeli plane flying over the sea. Then I heard shooting and bombing, and the Egyptian army shot down the plane and captured the pilot. It was the beginning of the war.4 Ibrahim found out from his colleagues that Israel had attacked Egypt, and he came and told us, so we moved downstairs where it was safer. The shooting became heavy and continuous and we didn’t know where it came from, or any other news, so we prayed, read verses from the Quran, and made Du’aa. The next day we heard that the Israelis had occupied Shaja’iyya, an eastern suburb of Gaza City, and then Al Nasser, a northern suburb. When I heard this, I told Ibrahim to take Fawaz and Hussein, who looked older than their ages, and leave. Ibrahim asked where they should go and I didn’t know, so I said, “Go anywhere. Go to the fields, the fields of grapes, the fields of fig trees, Wadi Gaza, anywhere, but don’t stay here. I don’t want to repeat what happened to my brothers in my home. Please take them to a safe place and hide.” He hesitated as he didn’t know where to go, but I insisted, so he left with the boys after I gave them a bag full of bread and food and some clothes. The boys were very afraid of the shooting and could hardly walk, but their father kept urging them to lift their feet and walk. They finally found shelter with other people who were hiding under fig trees in the fields of Sheikh Ejleen, a few kilometres south of our house.

The next day, Israeli soldiers came to our home. Nasser was young, and I used to send him to Um Yahya, the gardener’s wife, for bread. That day, he came to me and said, “I saw Israeli soldiers outside the walls of our home and they asked me about my family and told me to bring all of you, and raise your hands in the air.” We were downstairs with the gardener’s wife and children, watching from the small windows, when they ordered us outside, and I became so scared and thought it was now our turn to be killed. I called for the children to go out with their hands raised, and I tried to recite some small verses of the Quran, but my tongue couldn’t form the sentences and I couldn’t remember any verses, even the short ones. It was against my dignity to raise my hands, so I ran after the children raising and lowering my hands, pretending to show them and telling them to keep their hands raised. The children stared, because they were already doing this. Adala was very weak and thin because she hadn’t eaten anything for three days, and was wearing her uniform because the day the war started she was ready for school. She thought they would kill us like they had killed her uncle in front of her eyes, and she was shaking, while my other small children cried. The Israeli officer spoke Arabic and asked why she was shaking, and she said she was afraid they would kill us like they did her uncles. He asked who they were, and she gave their names, Hassan and Nadid Hafez Albatta. He told her not to be afraid because his soldiers had no intention of harming anyone.

I saw Abu and Um Yahya and their son, and also a neighbour who owned a shop, already facing the walls with their hands raised. The soldiers asked me where my husband was and I told them he was in Egypt, and when they asked why he was there, I told them that he had married another woman. When they saw us shaking, they told us not to be afraid and asked me about Abu Yahya and his son. I told him he was the gardener, and when he asked me about the shop owner, I said he was our neighbour. Then we were ordered back downstairs with Um Yahya, and they took the men, pointing their guns at their backs, toward the area in front of the house, which had been an Egyptian army camp. I was sure they were going to kill them, and as soon as we went inside, we heard shooting. I said, “I’m sure that they have killed them like they did in Khan Younis in 1956.” Adala and I looked at each other and both thought the same thing, but Um Yahya did not understand what had happened because she hadn’t had this experience. I don’t know how the time passed until the late afternoon, and then we saw Abu Yahya and his son, with their hands raised, returning. I couldn’t believe they were alive. They told us that many young people had been taken in buses and thrown out at the Sinai border with Egypt. Others had been killed, and the rest, who were old or very young, were ordered back to their houses.

I planted many vegetables such as cucumbers, tomatoes, mulokhia, mint, and other things in our garden. Once, Nasser went outside and ate some cucumbers, and Hamed followed him and brought one back to us. When I discovered this, I went crazy and shouted at them because I was afraid that if the soldiers saw them, they would be shot. They started to cry, and I realized that they were bored from being inside this small shelter for so long, so I organized things for them to do to fill their time. I didn’t want them to go outside at all because if they did, they might not return. Curfews were imposed every night from late afternoon until early morning, and sometimes during the day if there were problems, such as the Fedayeen shooting at the Israelis or their tanks or jeeps. Sometimes the curfews were lifted for a short time so people could obtain food. The next day, there was a short period in which the curfew was lifted, and my children helped collect some vegetables to give to neighbours who had big families and nothing to eat. At that time, even if the curfews were lifted, not many shops opened, and if they did there wasn’t much to buy. Once, when I sent my children with vegetables for the neighbours, on their way home, Moeen and Yahya played near a tank close to our home, and even climbed up and sat on it because no soldiers were there. When other soldiers saw the boys, they shot at them. I heard the shooting from my home and didn’t know what was going on. They quickly got down off the tank and crawled toward our home, and when the soldiers saw they were young children, they stopped shooting. The same day, Hussein and Fawaz came for more food because they had finished their supply, and they told me their father was well and waiting in the area beside Wadi Gaza. I gave them food and told Hussein to take Moeen with him, and Um Yahya asked them to take Yahya as well so they would be safe. The four of them took the food and returned to Ibrahim.

The war lasted for a week. Then Ibrahim and the children returned, and we went back upstairs to live, but everyone was afraid for a long time. The Israelis imposed curfews during the night and sometimes during the day for many years after 1967. In the beginning, the curfews were long, then they were gradually reduced to being only at night, and then stopped. As time passed after 1967, our hopes that they would withdraw after a few months, as in 1956, decreased. When the Israeli occupation controlled the area, we couldn’t travel to Egypt directly, but had to go first to Jordan through the West Bank and from there to Egypt. Adala and Hussein had finished their eleventh-grade exams, and one month after the war, when the way was open again through the West Bank and Jordan, we obtained permission from the Israelis to travel to the West Bank. We were optimistic that the Israelis might stay three or four months and then withdraw, and we didn’t want them to lose the school year because we didn’t know when the schools would reopen. So, we thought to send them to join their uncle in Kuwait to do their tawjihi. We went to Nablus and stayed with my uncle, and the next day Ibrahim took the children to the Allenby Bridge, where his brother was waiting on the Jordan side, and they went from there to Kuwait.

After the 1967 war, an Israeli administrative governor took over the Gaza Strip, and we went to his office to ask for identity cards for Hussein and Adala. I think his name was Beni Metiv. When he saw our name, he recognized the family and told us that he knew Ibrahim’s brother Abdallah. Metiv had been a commander of a battalion when Abdallah was a leader of a group of Fedayeen in Beersheba, and in the battle of Al Ma’in in 1948, he knew where Abdallah was and had wanted to find him and kill him. But, on that day, Abdallah had left the area and he didn’t know he had gone. When they occupied the Abu Sittas’ land, he entered their house and took all the books in their library and found some family photos, which he gave to us. He also gave us a book he had written in Hebrew, The Planters of the Desert, and wrote on its first page, “To the Abu Sitta family. I wish to God that there could be peace between us,” because he knew I understood Hebrew. This book is about Jews who lived in the Negev in the Dangur Colony (also called Nirim in 1949 and now has taken the name Nir Yitzhak), located approximately 15 kilometres from Al Ma’in. The book also mentions the above story concerning Abdallah. He spoke Arabic because he was a Jew who lived close to Al Ma’in where the Abu Sitta family lived, and he knew many things about the place and people. Then he issued the identity cards.5

After 1967, the Israelis tried to make Ibrahim return to work under the Israeli civil administration. An Israeli officer from the civil administration came to our home at midnight during a curfew and tried to convince Ibrahim, but he refused and said he couldn’t work in an occupation administration. They told him that he would be a director as before, but he said he would be one in name only, as there would be other Israelis over him to draft the plans he would be forced to implement. The soldiers knew that in Bedouin society a son respects his father’s words, so the officer went to his father and tried to convince him to make Ibrahim return to his work by saying he would need it to survive and feed his family. Ibrahim’s father told them, “What are you saying? Are you crazy? Have you lost your mind to think that my son would work in your government? Get out of my sight and don’t return.”

Ibrahim made this decision when the five Palestinian directors of the Egyptian administration decided that only the directors of health and education should return to their positions, because the nature of their positions was not political but administrative, so they would still be helping people. The remaining three directors resigned because their staying would not be helpful for the people; rather, it would have furthered the aims of the occupation. I supported Ibrahim in his decision because I believed that he would be useless and only fulfilling Israeli orders, not his own plans, so he would just be an instrument in their hands. So, we lived on a small pension from the Egyptian government, and every year he went to Egypt to collect it. We also have land in Deir Al Balah, so we lived off both. In fact, it was really hard for us after 1967. The income from the land was not enough because of the children’s education expenses, but Ibrahim’s brother sent money and supported us for a long time. We managed with that generous support, which continued until the children graduated and started to work.

The soldiers didn’t return, but they kept us in their minds. They deported and detained Ibrahim for three months in the Sinai Desert, after accusing him of organizing activities against the occupation.