Adaptive Running Methods

2

Adaptive running is not about reinventing the wheel of training for each athlete. There are certain training methods that I believe to be effective for every runner. Creating a customized training plan for yourself is simply a matter of learning these methods and applying them in the way that suits you best.

Even though I train each of my runners uniquely on the level of details, on a group level there are some general characteristics that each runner’s training shares with that of the others. These general characteristics represent the training methods that I have found to be beneficial for every runner, and therefore to be essential characteristics of any successful training program. There are 12 general methods that characterize my adaptive running system:

1. consistent, moderately high running volume

2. nonlinear periodization

3. progression from general training to specific training

4. three-period training cycles

5. lots of hill running

6. extreme intensity and workload modulation

7. multi-pace workouts

8. nonweekly workout cycles

9. multiple threshold paces

10. constant variation

11. one rest day per week

12. selective cross-training

Let’s take a closer look at each of these methods. This chapter is meant to serve as a general introduction to the methods you will use when practicing adaptive running. You will learn all of the details you need to know to apply these methods in subsequent chapters dealing with the specifics of designing workouts and training plans.

1. Consistent, Moderately High Running Volume

General running volume—or how much you run—is the most basic parameter of training and therefore the first parameter that each runner should consider in creating a customized training plan. How many times per week should I run? How many miles per week? How much should my running volume increase from the beginning to the end of my training plan? These are the questions you need to answer before asking any others as you look ahead to your next training cycle.

The running volume that is most appropriate for you depends on your next peak-race goal, your capacity to absorb and recover from frequent runs and longer runs, and your training history. As a general rule, I recommend that runners consistently maintain a moderately high running volume relative to these individual considerations.

Some training systems are characterized by extremely high volume rather than moderately high volume. In extreme high-volume systems, runners push themselves to run as many miles each week as they possibly can. Arthur Lydiard was a persuasive proponent of extreme high-volume training. Many of America’s top runners of the 1970s and early 1980s—including Frank Shorter, Bill Rodgers, and Alberto Salazar—were strongly influenced by Lydiard’s philosophy and achieved great success on high-mileage training (upwards of 150 miles per week in some cases).

Other training systems are known as high-intensity systems. In these systems, training intensity, not training volume, is considered to be the true path to running success. The weekly training schedule is packed with high-speed sessions that leave runners exhausted after relatively few miles compared to the number of miles they could complete at lower intensities. High-intensity training systems are necessarily moderate-volume systems, because the more high-speed running you do each week, the less total running you can do without becoming overtrained or injured. Many great runners have achieved outstanding success on training programs that emphasized quality over quantity. American middle-distance star Alan Webb and former marathon world record holder Steve Jones of Wales are among the most noteworthy runners to have reached the top by doing a lot of high-intensity workouts and less total mileage than most of their peers. Bill Bowerman, the legendary University of Oregon coach and Nike cofounder, also used a high-intensity, moderate-volume system with his athletes.

Based on the proven effectiveness of both approaches, I like to split the difference between the extremes in volume emphasis and intensity emphasis. I believe that high running volume is indispensable for maximal aerobic development. However, high-intensity training clearly provides fitness benefits that moderate-volume training does not. Since the only way to truly maximize running mileage is to forego high-intensity training, I believe that overemphasizing mileage is a mistake. Most runners will get the best results by finding a balance between quality (intensity) and quantity (volume). So the adaptive running approach is to do as much running at various faster speeds as you can do without seriously limiting the total running volume you can absorb, and to do as much total running as you can do without seriously limiting the amount of high-intensity running you can absorb. Naturally, the precise formula is different for each runner, and finding it requires experimentation.

Another aspect of my philosophy on running volume is consistency. Some training systems entail large fluctuations in running volume throughout the training cycle. I prefer to keep the overall running volume fairly consistent throughout the training cycle while manipulating other variables to produce fitness gains. Obviously, when an athlete’s recent training has been at a low volume it is necessary to gradually increase it to the level that is required for peak fitness. However, once a runner has attained this level, I like to have him or her stay relatively close to that level thereafter, except for brief off-season rest periods.

The rationale for consistency in running volume is, first of all, that it does no harm to maintain a relatively high volume year-round. As long as you take one or two breaks each year and reduce the overall workload of your training when appropriate, you won’t wear yourself down. Secondly, having to build your running fitness from a low level to the level required for peak fitness can really bog down a training program, because volume increases must be executed gradually to avoid overtraining and injuries, and it’s very risky to increase overall running mileage and high-intensity running mileage simultaneously. You’ll be able to build fitness faster and peak at a higher performance level if you start each training cycle with a relatively high volume of running. And the only way to safely start a training cycle at a fairly high volume is never to allow your training volume to drop too low.

A third benefit of maintaining moderately high running mileage more or less year-round is that it reduces injury risk. Injuries tend to occur during periods of increasing running volume. If you keep your mileage relatively high, you will minimize these risky volume ramp-up periods in your training.

2. Nonlinear Periodization

Every running coach uses a variety of types of training with athletes. Each specific type of training is intended to develop a specific aspect of running fitness. In my adaptive running system, aerobic-support training develops the aerobic system, muscle training cultivates the neuromuscular aspect of running fitness (i.e., speed, strength, and power), and specific-endurance training is used to layer a race-specific fitness peak atop the foundation of aerobic and neuromuscular fitness. Most other training systems involve a similar mix of training types, although there are significant discrepancies in the details.

The term “periodization” refers to how one’s training evolves from the beginning to the end of a training cycle. Periodization is considered linear when each period or phase of training is very different from the other periods in terms of the degree to which each training type is emphasized or deemphasized. Periodization is considered nonlinear when all of the training types are mixed together throughout the training cycle and changes in emphasis are less extreme. My approach to periodization is nonlinear.

Traditionally, linear periodization has been the more popular approach. And even today, a lot of coaches divide the training cycle into distinct phases and put a strong emphasis on just one type of training in each phase. By contrast, my training plans feature a more even balance of training types throughout the training cycle. My runners always work on every aspect of running fitness. The distribution of emphasis does change, but I do not reduce any training type to mere “lip-service” level, or phase it out entirely, as others do. The only exception is the final few weeks of training before a peak race, called the sharpening period, when we really zero in on race-pace training. I’ll say more about the sharpening period later in the chapter.

I believe it’s extremely important never to allow any single aspect of your running fitness to fall too far behind the others in your training, because they are all so deeply interdependent. The inevitable consequence of allowing, say, your neuromuscular fitness to stagnate while you work hard on your aerobic fitness and specific endurance is that lack of neuromuscular fitness will become a limiter to further development of the other two aspects of your fitness.

Some runners do not perform a weekly long run at the beginning of base training, but I like to introduce this type of training immediately and keep it there throughout the training cycle. Some runners do sprint training only during one brief phase of the training cycle, but my runners do sprints once or twice every week (on steep hills). In conventional training systems, lactate threshold training (described later in this chapter) is introduced in the middle of the training cycle. I prescribe threshold work from the very beginning and increase it steadily until the middle of the training cycle, after which time I may or may not taper it off, depending on the athlete’s primary race distance. But it never goes away. The same general pattern holds for every type of training that’s a part of the adaptive running system.

In addition to preventing weak links from developing, another advantage of nonlinear periodization is that it increases the adaptability of your training. When you keep all aspects of your running fitness at a fairly high level, you can take your training in any of a number of different directions fairly quickly based on what you seem to need. When you’ve recently neglected any specific type of training, it’s always necessary to ease into doing more of it—otherwise you risk becoming overtrained or injured. So if you suddenly find that a lack of muscle training has left you with a deficit of neuromuscular fitness (you’ll find out how to make such assessments in chapter 8), your only sensible course of action to correct this problem is to start doing small amounts of muscle training and gradually build neuromuscular fitness from its current low level. But if challenging muscle-training efforts have remained a regular part of your training, you can correct a neuromuscular fitness deficit much more quickly by aggressively boosting your muscle training without much risk of becoming overtrained (that is, chronically fatigued) or getting hurt.

3. Progression from General Training to Specific Training

One of the most important principles of sports performance is the principle of specificity. It refers to the fact that the body adapts very specifically to the demands placed upon it in training. Due to the principle of specificity, there is no such thing as truly all-around running fitness. The running fitness of every runner is always limited, reflecting the specific nature of the training he or she has done. For example, you might run 100 miles a week on the plains of Nebraska and consider yourself one heck of a fit runner, but when you compete in the Mt. Washington Road Race you get your butt kicked because your body is not specifically adapted to running up hills. Or you might be able to run a full marathon at a pace of eight minutes per mile, because you always train at this pace, but for the same reason, when you try to sustain seven-minute miles in a 10K race you come up short.

The most important ramification of the principle of specificity for competitive runners is that race-specific fitness requires race-pace training. Every competitive runner likes to achieve time goals in races. When you show up to a race with a particular time goal in mind, whether or not you achieve that goal depends on whether your body is able to sustain the average pace that is associated with your time goal over the entire race distance. The principle of specificity tells us that your body is most likely to have this ability if you have recently done some hard workouts that have challenged your ability to sustain your goal race pace. Doing highly race-specific workouts in your peak weeks of training will ensure that your body is specifically adapted to your particular race time goal.

The principle of specificity only goes so far, however. If you took this principle to the extreme, you would perform challenging race-specific workouts throughout the training cycle. The problem with this approach is that the body can only progressively adapt to this type of training for a few weeks before it reaches a temporary adaptive limit, or peak. Therefore it’s crucial to have a very high level of non-race-specific running fitness before you start to do race-specific workouts. By taking the time to build your fitness to a high level with an emphasis on the types of training that serve as a foundation for race fitness, you can perform your race-specific workouts at a higher level and therefore race at a higher level. But if you start trying to do race-specific workouts in the first week of a training cycle, when your base fitness level is relatively low, you will not be able to perform these workouts at a high level, and when you reach your adaptive limit four to six weeks later, you will not have made much progress from your starting point.

The term I use for the type of fitness that is required for successful racing is specific endurance, which represents the ability to resist fatigue at race pace. As mentioned above, there are two other types of running fitness that serve as elements of the foundation for race fitness: neuromuscular fitness and aerobic fitness. Neuromuscular fitness is basically the ability of your brain’s motor centers to efficiently activate large numbers of muscle fibers during running, which is required to achieve high speeds and to sustain high speeds in an energy-efficient manner. Aerobic fitness refers to the ability of the runner’s body to use oxygen at a high rate during running. In crude terms, neuromuscular fitness is the capacity to run very fast for a short duration and aerobic fitness is the capacity to run slow or moderately fast for a long duration. Together, these capacities represent the two “extremes” of running fitness.

Specific endurance, or race fitness, represents a blend of neuromuscular and aerobic fitness. Generally speaking, the higher you can elevate your neuromuscular or aerobic fitness, the higher you can raise your specific endurance. Therefore, my adaptive running approach to the overall training cycle is to first build a foundation by focusing on the extremes of running fitness. Gradually, I bring these extremes together by adding a little more of an aerobic element to neuromuscular training and a little more of a neuromuscular element to aerobic training. Finally, in the last few weeks of training, I focus on true specific-endurance workouts performed at or very near the runner’s goal race pace. In keeping with my nonlinear approach to periodization, specific-endurance training is always part of the mix, but it stays in the background until the sharpening period.

Traditionally, the term “sharpening period” (or “sharpening phase”) has been used to denote a brief period at the end of a training cycle when distance runners add short, high-speed intervals to their training to “sharpen” for a race. In the adaptive running system, the sharpening period denotes a short period at the end of the training cycle when runners emphasize challenging race-pace workouts. To avoid confusion, I sometimes tell people that I don’t “sharpen” my runners for racing at all, but that’s not quite accurate.

4. Three-Period Training Cycles

As alluded to above, in adaptive running, the training cycle is divided into three periods, or phases. The training cycle starts with an introductory period, which lasts just a few weeks; it then moves into a longer fundamental period; and it culminates in a sharpening period.

The purpose of the introductory period is to establish an appropriate fitness foundation that will prepare you for the more challenging and focused training of the fundamental and sharpening periods. Priority number one is to gradually but steadily increase your running mileage toward the level you have targeted as your average weekly running mileage for the training cycle. This will enhance your body’s ability to absorb the training of the fundamental and sharpening periods without injury or overtraining fatigue. Other priorities of the introductory period include establishing a foundation of neuromuscular fitness with very small doses of maximal-intensity running and beginning the long process of developing efficiency and fatigue-resistance at race pace with small doses of running in the race-pace range.

In the fundamental period, your training becomes increasingly specific. Your longest runs become more race-specific by first approaching race duration (if you’re training for a long race) and then by becoming faster. Your fastest runs become more race-specific by generally moving toward race pace and by challenging you to sustain fast speeds for longer and longer durations.

The purpose of the sharpening period is to raise your running fitness to its peak level, or, put another way, to make your running fitness as race-specific as possible. Peaking is a mysterious art. For whatever reasons, it’s just not easy to achieve one’s highest possible level of performance on the day of a major goal race, despite all the care that goes into planning one’s training to produce this result.

American runners at the top levels tend to run well early in the competitive season and fall flat toward the end of the season, when they should hit their peak. The reason, I believe, is that they start to do race-specific “sharpening” training too early in the training cycle. A runner’s body can only progressively adapt to race-specific training for a few weeks until a limit—that is, a peak—is reached. Trying to prolong race-specific training beyond a few weeks is almost certain to result in a premature peak or failure to peak at all. For this reason, I begin the sharpening period of training just four to six weeks before the athlete’s peak race occurs.

Merely limiting the duration of your sharpening period of training will not guarantee a successful peak, however. There are a few other tricks you can use to reliably increase the odds of peaking successfully. It’s all about understanding the factors that tend to trigger a peak and those that tend to delay a peak, and applying each factor as appropriate.

One factor that tends to delay a performance peak is maintaining balance in one’s training. A peak tends to occur when you push your fitness strongly in a single direction by heavily emphasizing a particular type of training. I take great pains to develop a high level of well-rounded fitness in my runners through balanced training before pushing their fitness in the direction of race-specificity in the final month of training.

Race-pace training is certainly included in the overall training mix before the final four weeks, but the amount is limited compared to other training paces. Then, in the sharpening phase, I have my runners really home in on the race-pace range to effect a quick, quantum leap in race-specific fitness. Now is no longer the time to be a well-rounded runner. You want to be as good as you can be at only one thing: running at your goal race pace over the full race distance.

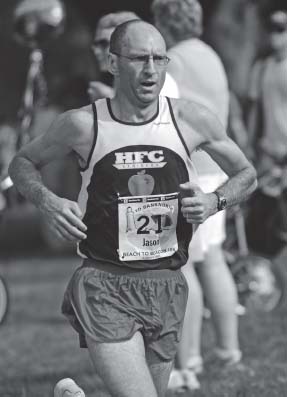

In the adaptive running system, you will maintain a consistently high level of well-rounded fitness. © Alison Wade

If you can achieve a handful of workout performances in the sharpening period of training that are almost equivalent to your goal race performance, your attainment of that goal will be all but guaranteed (as long as you rest up adequately before the race). To achieve such workout performances, you must first of all be very close to race fitness, thanks to the training you’ve done up to this point; second, you must be sufficiently recovered from recent training to perform near your best; and finally, the format of the workout must be very similar to the race itself. For example, if you’re peaking for a 10K, your toughest sharpening workout might consist of 6 × 1 mile at 10K race pace with very short, 60-second active recoveries.

5. Lots of Hill Running

People who know only a little about my training system seem to know me as the coach who has his runners do a lot of hill sprints. Short hill sprints are an integral feature of my training system, and one that I use with every runner. However, this method is no more important than any of the 11 other adaptive running methods discussed in this chapter. Nor am I the only coach who uses steep hill sprints. In fact, I myself borrowed the specific approach to hill sprints that I now use from the Italian coach Renato Canova, who in turn learned about them from an American sprint coach named Bud James.

Like the other core training methods in my system, hill work is used throughout the training cycle. The amount and type of hill training varies, however. We start with very short sprints—approximately eight seconds apiece—at maximal intensity on the steepest hill we can find. The nature of this challenge is not much different from that of a set of explosive Olympic weightlifting exercises in the gym, except it is more running-specific. These short, maximal-intensity efforts against gravity offer two key benefits. First, they strengthen all of the running muscles, making the runner much less injury-prone. They also increase the power and efficiency of the stride, enabling the runner to cover more ground with each stride with less energy in race circumstances. These are significant benefits from a training method that takes very little time and is fun to do.

As the weeks go by, we gradually increase the number of sprints performed in each session. The intervals also become slightly longer (increasing to 10 seconds and finally to 12 seconds), and we may move to less-steep gradients. This process serves to make the gains in strength, power, and muscle fiber recruitment more specific to race-intensity and race-duration running.

Hill running is the only “weightlifting” my runners do. They hoist no barbells or dumbbells. They do some exercises to develop strength in their abdominal muscles and lower back, but that’s it. Some other runners lift weights to build strength and prevent injuries. I believe that short hill sprints achieve the same effect. A number of the runners I’ve coached over the years have come to me with long injury histories, but in every such case I’ve been able to keep them healthy, and I attribute much of this success to hill work.

For example, for three years I coached a very talented high school runner who was also very injury-prone. Her parents brought her to me because every time she tried to take her training workload to the next level, she developed a stress fracture. When I started working with her, I had her start doing hill sprints. She quickly became noticeably stronger and her injury problems vanished. Incidentally, her best mile time dropped from 5:30 to 4:54 in one year.

In addition to hill sprints, I make frequent use of longer hill repetitions and uphill progressions. Hill repetitions are essentially speed work with an added hill component. They put less strain on the legs than traditional speed work, making them a good alternative early in the training cycle for all runners as well as for those limited by their strength. Uphill progressions are prolonged stretches of uphill running (10 minutes or more) at the end of an otherwise easy run. They are an effective way to increase the aerobic training stimulus and the strength-building stimulus of a workout without taking too much out of a runner.

6. Extreme Intensity and Workload Modulation

Intensity modulation refers to changing the pace level or levels that are targeted from workout to workout. Extreme intensity modulation means changing target pace levels more frequently and to a greater degree throughout the typical week of training than most runners do. Workload modulation refers to changing the overall challenge level of a workout from one run to the next. (Bear in mind that a high-intensity workout is not the same thing as a high-workload workout. Very fast runs can be relatively easy if they’re also short, while moderate-pace runs can be quite challenging if they’re long enough.) Extreme workload modulation means mixing workouts of widely varying challenge levels throughout the week.

I believe in doing two hard workouts per week, not including the weekend long run. By “hard workouts” I mean workouts involving a moderate to large dose of high-intensity running (half-marathon race pace or faster). It can be a somewhat misleading term, because the weekly long run can be the most challenging run of all for certain runners at certain times (especially toward the end of a half-marathon or marathon training program), but I’ve been using the term forever and I’m too old to change. I use the term “key workouts” when referring to the weekly long run and the twice-weekly hard workouts together.

Some elite runners try to pack in three hard workouts during the week—that is, three workouts featuring moderate to large volumes of high-intensity running. You might say that these runners train harder than my runners, who only do two. I’m not so sure. In fact, my observation has been that, over time, runners accomplish more hard training, or at least absorb more hard training, when they do two hard workouts per week instead of three. This happens because you work hardest on your best days—that is, on the days when you feel freshest and most ready. Runners are able to perform at a higher level in their hard workouts when they do just two a week because they have more opportunity to recover between them.

In simple terms, what I’m saying is that two really hard workouts per week are better than three merely hard workouts. I believe that workouts have the greatest fitness-boosting effect when they take you to a higher level of performance than you have previously achieved in the present training cycle. In order to take you to a higher performance level, the workout must be demanding in duration and intensity, but it also must occur when your body is fully up to this challenge. Having more recovery time between hard workouts enables you to perform better in each hard workout, which enhances the fitness-boosting potential of each hard workout—provided you once again give your body a chance to absorb it.

Fatigue masks fitness. When you start a workout carrying fatigue from previous workouts, you will not perform as well as you should. Consequently, the workout will have limited effect on your fitness, even if you do rest adequately afterward. Some competitive runners fear that giving themselves more opportunity to recover necessarily means that they do not train as hard. But in fact, more often than not, giving yourself adequate recovery time enables you to train harder by setting you up to perform at a higher level in your most important workouts.

In addition to limiting the number of high-intensity workouts to two per week, adaptive running also brings back the lost art of the moderate run. For many years, the motto “go hard or go home” has been an accurate representation of how most coaches approach training. Either you’re doing a very hard run to stimulate fitness adaptations or you’re doing a very easy recovery run to help absorb the previous hard run and prepare for the next. But a weekly schedule that entails only two hard runs makes it possible to also do one or two moderate runs (in addition to easy recovery runs) without hampering your recovery from a previous hard run or sabotaging your performance in the next.

I think it’s worth taking advantage of this opportunity to do moderate runs for the simple reason that a moderate run provides a stronger training stimulus than an easy run. So if your body can effectively absorb one or two moderate runs per week in addition to two very hard runs, it just makes sense to do those moderate runs instead of the easy runs you would do according to the “go hard or go home” philosophy.

Naturally, the terms “hard,” “moderate,” and “easy” are relative. To give you a sense of what I mean by a moderate workout, let me supply one example. Suppose an appropriate hard workout for you at a given stage of training consists of 5 × 1K at your current 5K race pace with three-minute active recoveries, sandwiched between a two-mile warm-up and a one-mile cool-down. A typical easy recovery workout is 30 minutes of easy jogging. A moderate workout, then, might be a 15K progression run in which you run the first 10K at an easy pace and the last 5K at roughly marathon pace.

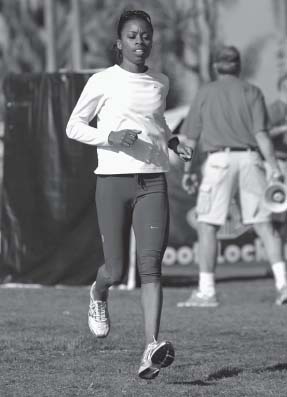

Elite miler Treniere Clement shows it’s okay to run slow sometimes, even if you’re very fast. © Alison Wade

If the hard workouts tend to be especially hard in the adaptive running system, the easy workouts are often equally extreme at the other end of the workload spectrum. The single most common training error I see in competitive runners is running too hard on supposed easy days. There’s no shame in running slow. Running slow allows you to run longer, and it also enables you to run harder when you want to run hard. A longer, slower recovery run is better than a shorter, faster one, because a longer recovery run adds more volume to your training, and again, volume is the number-one determinant of running fitness.

I’ve also found that very slow recovery runs are less likely to leave runners feeling flat in their next hard workout, even when they are longer than the all-too-typical moderate-pace “recovery” run. Many runners fail to recover adequately from their hard workouts because they run too hard on their easy days. As a result, their performance suffers in their next hard workout. A vicious circle is formed.

Wearing a heart-rate monitor on your easy runs is a good way to keep yourself honest. By wearing a heart-rate monitor regularly in your training, you will gain accurate knowledge of the heart-rate range that is associated with a moderately easy effort. When you set out on an easy run, control your pace to keep your heart rate within that range. Your restraint will pay off the next time you’re supposed to run hard.

Table 2.1 Adaptive Running Pace Levels |

|

In running, exercise intensity is understood in terms of pace. The following table lists all of the pace targets used in adaptive running workouts and also identifies the type of training stimulus each of them provides, the type of workouts each is used in, and an example of such a workout. You will learn much more about how these target pace levels are used in adaptive running workouts in subsequent chapters. |

|

Running Pace/ Intensity |

Training Type |

Workouts Used In |

Example Workout |

|

Easy (a pace that feels subjectively comfortable) |

Aerobic |

Easy (“recovery”) runs, some long runs, progression runs |

Easy Run |

|

Moderate (a pace that feels comfortable with a mild aerobic strain) |

Aerobic |

Moderate runs, some progression runs |

Progression Run |

|

Hard (a pace that feels hard but manageable relative to distance) |

Aerobic/Specific Endurance |

Some progression runs |

Progression Run |

|

Marathon Pace (your per-mile marathon pace in peak condition) |

Aerobic/Specific Endurance |

Threshold runs, marathon-pace runs |

Marathon-Pace Run |

|

Half-Marathon Pace (either your current or goal half-marathon pace, depending on workout) |

Aerobic/Specific Endurance |

Threshold runs |

Threshold Run |

|

10K Pace (either your current or goal 10K pace, depending on workout) |

Aerobic/Specific Endurance |

Threshold runs, specific-endurance intervals, ladder intervals, hill intervals, fartlek runs |

Specific-Endurance Intervals |

|

5K Pace (either your current or goal 5K pace, depending on workout) |

Specific Endurance |

Specific-endurance intervals, ladder intervals, hill intervals, fartlek runs |

Hill Intervals |

|

3K Pace (your known or estimated race pace for 3,000 meters or 2 miles |

Muscle Training |

Speed intervals, ladder intervals, hill intervals, fartlek runs |

Fartlek Run |

|

1,500m Pace (your known or estimated race pace for 1,500 meters or 1 mile) |

Muscle Training |

Speed intervals, ladder intervals, fartlek runs, strides |

Ladder Intervals |

|

Maximal Effort |

Muscle Training |

Steep hill sprints |

Example |

7. Multi-Pace Workouts

Multi-pace workouts represent a training method that I use to achieve greater intensity modulation in the adaptive running system. Most traditional running workout formats focus on just a single pace, or intensity level. For example, in a standard long run, the runner holds a steady, moderate pace long enough to develop a moderate to high level of fatigue. In a standard speed workout, a runner might run 12 × 400 meters at 1,500-meter race pace. Yes, there is also easy running in such workouts, in the form of a warm-up, a cool-down, and “active recoveries” between the hard 400-meter intervals, but this easy running only serves to facilitate the 1,500-meter-pace running, which is the one true target intensity of the workout.

Workouts featuring multiple-intensity targets are certainly not unheard-of in competitive running, but adaptive running relies on them far more heavily than most coaches do. Examples include ladder interval workouts, which may feature intervals of one minute to six minutes in duration, with the shortest intervals run at 3,000-meter race pace and the longest intervals run at 10K race pace; progression runs, in which the first segment is run at an easy (comfortable) pace and the last segment at either a steady faster pace or a gradually accelerating pace; and hybrid workouts that include threshold running at 10K or half-marathon pace and hill repetitions. What’s great about such workouts is that they enable you to include more intensity variation in each week of training than you can when you force yourself to focus on a single target intensity in most workouts.

There are times in the training process when your body might benefit most from a small amount of a particular type of training, such as “speed” training at 1,500-meter to 3,000-meter pace. With multi-pace workouts, it’s easy to get a small dose of speed training or another training intensity level when you need it. But if you’re too reliant on traditional methods, you’re faced with a choice of either devoting an entire workout to this type of training, and therefore getting more than you need, or foregoing it, and therefore not getting enough.

8. Nonweekly Workout Cycles

Another method I use to facilitate intensity modulation in training—which goes hand in hand with multi-pace workouts—is not locking myself into rigid one-week cycles. It’s traditional to do one workout of any given type per week, excluding easy runs: one threshold run, one interval workout, one long run, and so forth. But there are times when, for example, you might benefit most from doing more than one threshold run per week—perhaps one-and-a-half (i.e., one long threshold run and one short one) or even two would be ideal—or less than one threshold run per week—perhaps only half a threshold workout (i.e., one short threshold run), or one every 10 days.

In the adaptive running system, it’s okay to break any convention you wish to break in pursuit of getting the right amounts and proportions of training at various intensity levels. Single-pace workouts and one-week cycles are used when and only when they serve this end. When they cannot, never hesitate to use multi-pace workouts and nonweekly cycles to achieve the right mix.

9. Multiple Threshold Paces

In conventional training systems, “threshold training” refers specifically to running at a pace corresponding to one’s lactate threshold (also known as the anaerobic threshold). In my adaptive running system, threshold training has a different meaning. Specifically, I deal with multiple thresholds, of which the lactate threshold is one.

The problem I have with one-dimensional threshold training is that it lacks specificity to race goals. A runner’s race goal is to sustain a certain pace over a certain distance. Lactate-threshold pace—or the running pace at which the blood lactate level begins to spike—falls between 10K race pace and half-marathon race pace for most runners. Well, that’s a perfectly useful training pace in some circumstances, but there’s nothing magical about it. Somewhat slower and somewhat faster training paces are equally useful in other circumstances. The specific “threshold” pace that is most beneficial to a given runner at a given time depends on the race distance he or she is preparing for, the runner’s goal pace, and how far along the runner is in the training process. A mistake that is made in many training systems with respect to threshold training is to overuse the lactate threshold and underutilize other alternatives.

The approach I prefer is to use at least three distinct threshold pace levels in training and to carefully sequence them to develop more and more race-specific fitness. I don’t really care how much lactate my runners have in their blood at any given running pace. I care how long my runners can sustain their goal race pace and how fast a pace they can sustain over their goal race distance. The purpose of threshold training is to increase the duration a runner can sustain pace levels approaching race pace and/or to increase the pace a runner can sustain over distance.

So, what are the three threshold pace levels? The first threshold is the fastest pace the runner could sustain for 2.5 hours, or a little slower than marathon pace for my male runners. The second threshold is the fastest pace the runner could sustain for 90 minutes, which is a little faster than marathon pace for my male runners. And the third threshold is the fastest pace the runner could sustain for one hour, which is half-marathon race pace or a bit faster for my male runners.

For sub-elite runners, the three thresholds are more likely to be marathon pace or a little faster, half-marathon pace, and a little slower than 10K pace. When you practice adaptive running, you can simply run your threshold workouts at your real or estimated marathon pace (minus a few seconds per mile), half-marathon pace, and/or 10K pace (plus a few seconds per mile). There’s no need for scientific precision. The advantage of the multi-pace approach to threshold training is not greater precision but greater variability, so you can do threshold workouts that are a better fit for your needs at any given time.

10. Constant Variation

Variation is intrinsic to my adaptive training system in the sense that I include several different types of workout in each week throughout the training cycle. It is also intrinsic to the progressive nature of the system. Workouts of the same type become more challenging from one week to the next to take advantage of increasing fitness and to stimulate even greater fitness gains. But I also like to include some variation for variation’s sake in my training—little wrinkles in workouts that don’t have any particular rationale beyond forcing the runner’s body and mind to experience the unfamiliar or unexpected.

For example, on a Tuesday I might have one of my runners perform a fairly standard 10K-pace threshold run on flat roads. The next Tuesday I might have the runner cover the same distance at the same intensity level on a trail with steeply undulating hills. The next Tuesday I might move the runner back to the road and insert a 100-meter burst at 1,500-meter race pace at the end of each kilometer.

There are several benefits of such variation. Much of the fitness improvement we experience through training comes as the result of improved communication between the brain and the muscles. The brain learns to activate muscle fibers it was formerly unable to activate, discovers energy-saving ways of timing the activation of different muscles in the unfolding of the stride action, learns how to better relax muscles that don’t need to be active in certain phases of the stride, and so forth. The primary factor that stimulates these sorts of learning is variation. Each time you change the way you run, your brain is forced to change the way it communicates with your muscles, and in facing this challenge your brain makes discoveries that allow you to run more efficiently and powerfully thereafter. So the more variation you can include in each week of running—within reason—the better. Pace, surfaces, gradients, duration, fatigue states, and even shoes are among the variables you can manipulate to stimulate stride refinements.

Variation also reduces injury risk. If you run at the same pace on the same surface in the same shoes all the time, the tissues of your lower extremities face a tremendous amount of repetition in the type of stress they experience. Impact forces will concentrate in the same spots to the same degree, stride after stride, workout after workout, causing damage to accumulate. Varying your training spreads the stress around more, so that no particular spot absorbs more than it can handle. The principle is similar to that which is used on some assembly lines, where workers rotate among different specific tasks to prevent carpal tunnel syndrome.

Other benefits of constant variation are less tangible. The mental exercise of dreaming up little wrinkles to incorporate into your workout each day forces your mind to engage with your training on a deeper level. You’re less likely to mentally coast through your training on “autopilot”—just putting your body through each preplanned workout and moving on. The key to making adaptive running work is paying very close attention to your body’s response to training, learning about yourself as a runner, and using the information you gather to steer your training in the most appropriate direction day by day. Challenging yourself to vary your training for variation’s sake is a simple means of becoming more mindful of your running—of developing that internal coach’s perspective that you need to excel.

11. One Rest Day per Week

Almost all of the runners I coach are at the world-class level. They are genetic lottery winners, born with the innate potential to run very fast over great distances and the ability to absorb the staggering amounts of hard training that are required to fully realize this potential. Yet none of my athletes is exempt from the need for rest. No runner has ever been capable of training hard every day of the week, every week. That’s why I prescribe one day of rest per week for each of my runners (and more whenever necessary).

Rest is relative. A rest day for my elite runners might not be the same thing as a rest day for you. For them it’s usually a 45-minute run at a very easy pace. For you, and for most runners, a rest day is more likely to be a day without exercise, or at most some core-strengthening exercises. The point is to set aside a day to subject your body to much less training stress than you usually do. If you normally run 12 to 15 miles a day in two workouts, at least one of which involves some high-intensity efforts, then a single, slow, 45-minute run certainly qualifies as less taxing than normal and will very likely allow you to absorb your recent training and perform well in tomorrow’s training. However, runners who normally run approximately 45 minutes a day in one session will be required to run much less, engage in some gentler form of exercise, or skip exercise altogether to achieve the same benefits of absorbing recent training and preparing for the next hard workout.

Rest days play a crucial role in effective training. It’s easy for competitive runners to lose perspective and think they need to run to the point of at least mild fatigue every day. But this mentality is based on a misunderstanding of how the body adapts to training stress. Simply doing a workout does not guarantee that your body will adapt to that workout. There is a difference between doing a workout and absorbing the workout. If you follow up a hard workout too soon with another hard workout, chances are your body will not have a chance to absorb—that is, change in response to—the first workout. Rest, or at least relative rest, is required to absorb a hard workout. Rest days provide this opportunity.

There is such a thing as too much rest, though. I strongly recommend that competitive runners seeking to improve their race times run six or seven times a week, even if a couple of those six or seven runs are very slow and easy. It is difficult to achieve the volume of running that is required for improvement on fewer than six runs per week. Furthermore, it’s important to do some type of vigorous exercise at least six days a week simply to stay lean and maximize your overall health.

12. Selective Cross-Training

The best way to improve your running is to run. However, other types of exercise may benefit runners by improving performance, reducing injury risk, and helping them work through injuries without losing too much fitness. These days, I’m seeing more and more runners who seem to cross-train just to cross-train. I believe in a very selective approach to cross-training. I encourage my runners to do only as much cross-training as they need, when they need it.

One form of cross-training that all runners should do consistently is core-strength training. Exercises such as stomach crunches and side step-ups strengthen muscles that play key roles in stabilizing the joints during running. The more stable your knees, hips, pelvis, and spine are when you run, the less chance you have of getting injured. A little core-strength work goes a long way. I recommend doing five or six exercises two or three times each week. The most important muscles to target are those of the upper and lower back, buttocks, hips, lower abdomen, and thighs.

Alternative forms of cardiovascular exercise, such as bicycling, can be useful when running is painful or impossible due to an injury. The best way to approach alternative cardiovascular exercise is to duplicate the planned running workouts you’re missing as closely as possible in whichever alternative activity you choose. For example, if you had planned to do a 10-mile progression run with the last two miles at a moderate pace, instead do a 75-minute bike ride with the last 15 minutes at a moderate intensity.

That’s about all I’m going to say about cross-training in this book, because that’s about all there is to it, in my approach. For more detailed guidelines on incorporating cross-training into your program, check out Runner’s World Guide to Cross-Training by my coauthor, Matt Fitzgerald.

Sarah Schwald © Alison Wade

Runner Profile: Sarah Schwald

Sarah Schwald was one of the few athletes that I actively recruited. I saw her run in the 1,500 meters at the USA National Track and Field Championships in 2005. Based on close observation, I believed she was the most talented female runner at those championships, yet I also saw a lot of unrealized potential in her. She had great stride mechanics and a very elastic footstrike. I felt she would make a terrific 5,000-meter runner with proper training.

I knew that Sarah’s previous coach, Peter Tegen, had heavily emphasized very high-intensity work—short intervals at 1,500-meter race pace and faster—with Sarah. To make her stronger aerobically in preparation for moving up to the 5,000, I reduced her speed training and introduced longer intervals, lots of threshold work, and more mileage. After several months on her new program, Sarah was recording workout performances that indicated she was capable of running under 15 minutes for 5,000 meters.

Unfortunately, despite her progress, Sarah left me for another coach after just one year and never did move up to the 5,000. The one mistake I made with her, I believe, was reducing her speed training a little too aggressively. Only toward the end of my time with her did I realize that she was capable of handling a fair amount of high-intensity work along with all of the aerobic stuff and, indeed, would thrive best on this mix.

My first year with any runner is mainly a learning year. I do the best I can to train the athlete optimally based on close analysis of his or her strengths and weaknesses, my knowledge of the runner’s past training, and our goals. But in every case, observing the runner’s response to that first year of training provides a wealth of new information that allows me to train him or her much more optimally the following year. That’s why few things frustrate me more than getting only one year with a promising runner.

Expect your first year of adaptive running to be largely a learning year for you, too. Don’t get me wrong: You will make plenty of progress in your first adaptive running training cycle. But in closely observing your response to this training you will learn many valuable lessons about yourself as a runner that will enable you to make substantially more progress the next time around.