Improving from Year to Year

9

If you take up the sport of distance running as a child, you can expect to continue improving until you’re well over 30 years of age, and to remain at your performance peak until you’re pushing 40. And regardless of how old you are when you start running, you can expect to be able to improve gradually for at least six or seven years. So if you start running at age 40, there’s a pretty good chance you will be significantly faster when you’re 47.

There’s a difference, of course, between being able to improve over such a long period of time and actually doing so. Many runners who would love nothing more than to continue improving for many years hit a premature peak due to inconsistent training, injuries, failure to build properly on past training, failure to learn from experience, or even failure to believe in their ability to reach higher. Most runners who stop improving before they feel they should blame another factor: lack of time for the additional training that’s needed for ongoing improvement; but this notion is a fallacy. I’ve never met a nonelite runner who was training so perfectly that he or she could only improve by training more.

Taking the long view is an important facet of adaptive running. After all, adaptation of any sort takes time, and to achieve any significant degree of adaptation, such as reaching one’s genetic limit of physiological adaptation to running, usually takes a very long time. As a coach, my ultimate objective is not just to help my runners achieve their goal for the next race or the upcoming season; rather, it is to set each runner on a steady course of improvement and to keep him or her on that course of improvement as long as possible. Above all, I want my runners to race better this year than last year, and to race better next year than this year.

There are six keys to improving from year to year as a runner. I keep each of them constantly in mind when charting a course for the development of my athletes. The six keys are:

1. Consistency

2. Avoiding injuries

3. Building on past training

4. Learning from experience

5. Experimentation

6. Setting higher goals

Let’s take a close look at each of them.

Consistency

When you stop running or reduce your training workload, the fitness adaptations that you worked so hard to achieve begin to reverse themselves. Exercise scientists refer to this process as “detraining.” The rest of us refer to it as getting out of shape. Different aspects of detraining proceed at different rates, but most of them proceed all too quickly, producing an almost immediate and rapidly worsening decline in performance. For example, the concentration of aerobic enzymes in the muscles may begin to decline within two days after a runner stops training. A study from the early 1990s found that performance in a high-intensity treadmill running test decreased by more than 9 percent in a group of runners who stopped running cold-turkey for two weeks. Other research has shown that runners lose fitness when their training is interrupted at a significantly faster rate than they gain fitness when they ramp up their training.

It is very difficult to improve as a runner without consistency in your training. When a reduction or interruption in training causes you to lose fitness, you dig a hole for yourself that takes much longer to climb out of than it took to create. By contrast, when you maintain a solid foundation of fitness through consistent training, it is much easier to achieve a higher level of performance through modest short-term increases in training workload and/or improvements in training practices.

Lack of consistency in training is one of the most common barriers to improvement in nonelite competitive runners. Some training interruptions are caused by injuries, which I will discuss in the next section. But there is another common type of training lapse that is more easily avoided: off-season slacking. Many runners simply voluntarily get out of shape during the winter, when the weather is foul, the days are short, and there are no races on the horizon. Having lived, trained, and coached for many years in Boulder, Colorado, where the winters can be truly savage, I have empathy for those runners who slack in the off-season. I would even say that a certain amount of off-season slacking is acceptable and even healthy. Everyone needs a break now and then. But the unavoidable fact is that if you want to improve from year to year, you have to stay in decent shape through the winter.

It isn’t too difficult to get a break from the physical and mental grind of race-focused training without losing much fitness. You can cross-train indoors (cycling, aerobics, etc.) or outdoors (snowshoeing, mountain biking, etc.) to keep your aerobic system sharp while at the same time escaping the pounding of running and enjoying the motivational boost that comes with variation. You may even enhance some aspects of your fitness—particularly your strength—by focusing on certain types of cross-training that you have less time for during the rest of the year. Calisthenics, weightlifting, and Pilates workouts are all good options. But whatever you do, don’t go cold turkey on running. A week’s break is fine, but otherwise you should try to run at least twice a week throughout the winter to maintain the adaptations to repetitive impact that only running provides and that take so long to regain once you’ve lost them.

If you are a longtime off-season slacker, I think you’ll be amazed to discover how much easier it is to reach a higher level of performance in the spring if you maintain a solid foundation of fitness over the winter.

Avoiding Injuries

Injuries are the most common factor that thwarts training consistency at all levels of the sport of running. Improvement in running is very difficult to come by if you’re frequently injured. But if you’re able to stay healthy for an extended period of time and avoid other training interruptions, improvement becomes virtually automatic.

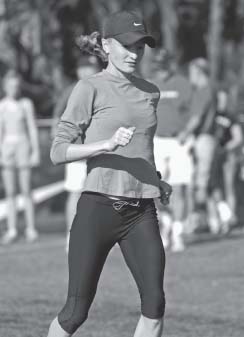

Over the years I’ve observed many cases of runners who achieved stunning levels of improvement simply by overcoming a pattern of bodily breakdowns and getting into a groove of steady training. A great example is Shalane Flanagan. A promising runner in her college and early professional years, Flanagan saw her career seriously derailed in 2005, at age 25, when she developed a major foot injury that required surgery and months of rehabilitation to fix. When she was finally able to return to normal training, Flanagan felt a renewed hunger to improve, and improve she did. In January 2007 she smashed her personal best time for 3,000 meters indoors by 21 seconds, clocking 8:33—a new American record. Three months later, she bettered her 5,000-meter PR by an equal amount, setting another new American record in the process. Flanagan’s mid-career breakthrough shocked many people, including her, but the recipe was nothing new: Consistent, dedicated training unleashing potential previously hidden by injuries.

Shalane Flanagan © Alison Wade

Preventing injuries is the most important priority of training. Injuries foil progress more than anything else, yet the harder you push for progress in your training, the more likely it is that you will get injured. Thus, if you don’t prioritize injury prevention with specific practices, you’re very likely to break down sooner or later.

The most effective way to prevent injuries is to avoid running in pain. Whenever unusual pain manifests in a bone, muscle, or joint, stop running and don’t start running again until you can do so pain-free. The surest way to prevent pain from emerging in the first place is to never increase your training workload abruptly or do workouts that are substantially harder than any workout you’ve done recently. Maintaining a consistently high running workload will help you avoid making such dangerously sudden increases.

As I’ve mentioned more than once already, running steep hill sprints at least once a week drastically reduces injury susceptibility by significantly strengthening the muscles and joints. Traditional core-muscle training is a good supplement to hill sprints. Running with proper technique is also important. If you’re a heel striker, learn to run flat-footed. This will reduce the risk of knee injuries and shin splints especially. Always wear the lightest, most comfortable running shoes you can find, and replace them every 500 miles. Finally, healthy eating plays a key role in injury prevention as well. Include a nice balance of food types (fruits, vegetables, meats, dairy, seafood, and whole grains) in your diet, minimize the amount of processed, sugary, and fried foods you consume, and make sure you get enough calories.

Building on Past Training

Each training cycle you complete changes your body. When you begin a new training cycle, you are not the same runner you were when you started the last one. Therefore, you should not train in precisely the same way that you did in your last training cycle, no matter how successful it was. In fact, in some ways, the more successful your last training cycle was, the more you can and should change the next one.

For example, suppose you struggled to handle the volume of running you planned for your last training cycle. If this is the case, the last thing you want to do is increase your training volume in the next training cycle. But you just might be able to handle the same running volume more comfortably in the next one, supposing you take a short break to rejuvenate your body and ease back into hard training. If, on the other hand, the running volume you planned for your last training cycle seemed ideal—enough to build your fitness to a high level but not so much that you struggled with it—then you’ll probably be able to increase your running volume slightly in the next training cycle. The “summit” of your recently completed training cycle is now the foundation for the next.

Increasing your training volume is the simplest way to stimulate year-to-year improvement by building on past training, but it is not the only way, nor is it always the best way. At some point in their development, all runners reach a point where their training volume is either as high as they can take it without sacrificing the quality of their workouts, or as high as they care to take it given the need to balance running with other priorities in life. After this point is reached, the only way to build on past training is to increase the specificity of your training. And even before you reach your lifetime running-volume limit, increasing the amount of race-specific training you do from year to year is an important way to build on past training and stimulate further improvement.

Over the course of your running career, the arc of your training evolution should move from generality toward specificity, just as it does within each individual training cycle in the adaptive running system. When you start running, your training should place a heavy emphasis on aerobic development and muscle training—the twin foundations of running fitness. Your specific-endurance training should be limited; do just enough to sharpen up for races. In subsequent training cycles, build on your foundation by increasing your total running volume and by doing tougher aerobic workouts (longer and faster long runs and threshold runs) and more challenging muscle-training sessions.

When foundation-building has taken you about as far as it will take you, begin adding more and more specific-endurance work to your training—that is, more work in the 3K-to-half-marathon pace range. Each year, find a way to add slightly more of this type of training to your regimen, whether it is by introducing it earlier in the training cycle, by doing longer specific-endurance workouts, or by adding a little extra specific-endurance work into other workouts besides those that are entirely focused on specific endurance.

The movement from generality to specificity can only go so far, of course. Even the most seasoned runners can only handle so much specific-endurance training. Moderate aerobic-pace running will necessarily always account for the majority of your weekly miles, because your body can handle a lot of this type of training and because doing a lot of it gives you a foundation to handle more specific-endurance training. Your year-by-year increases in specific-endurance training should be quite modest and should cease as soon as you reach a point at which you feel you’re doing as much specific-endurance running as your body will ever be able to handle.

Very few competitive runners really take advantage of this long-view approach to training evolution. By becoming one of the few who do, you will improve much more steadily and for a longer span of time than you would otherwise.

Learning from Experience

Perhaps the most important skill you can develop to foster improvement in your running is that of learning from experience. By that I mean paying attention to how your body responds to various training patterns, determining what works for you and what doesn’t, and modifying your future training to include more of what does work and less of what doesn’t. The most valuable service I provide the runners I coach is the application of this skill to their training. Cultivating the ability to learn from experience is the key to becoming an effective self-coach.

The reason that the ability to learn from experience is so important is that each runner is unique. If the same training methods worked equally well for every runner, there would be no need to pay attention to how your body responds to them. But because there’s no predicting how your body will respond to individual workouts, let alone long-term training patterns, ongoing improvement depends on your ability to assess the effectiveness of workouts and training patterns and to make appropriate adjustments based on these assessments.

Day-by-day adjustments are needed to keep your training on track toward a particular race goal, but year-to-year improvement requires a broader scope of analysis. In November or December, after the year’s last race is in the books, I sit down with each of my runners to comprehensively analyze the past season. We talk about what went right and what went wrong, and we try to identify the training patterns that seemed to do the most good and those that seemed to do more harm than good. Based on these discussions, we make some decisions about how we’ll approach next year’s training: what we’ll do similarly and what we’ll do differently.

You should do the same thing as a self-coached runner. During your off-season break, set aside some time to look at your training log and race results with a view toward identifying any specific lessons they might offer. A full year of training and racing is hardly a controlled experiment. There are so many variables at play that it’s impossible to establish precise cause-and-effect relationships between particular training patterns and particular fitness results with perfect certainty. But if you have indeed paid close attention to your body over the course of the year and kept a good training log, your hunches will generally be fairly accurate. Following is a list of questions you might want to ask yourself during your year-end review, plus some ideas about how to use your answers in planning your approach to next year’s training.

Did I perform as well as expected in my peak races?

The ultimate objective of your training is to maximize your performance in peak races. So your peak-race performances are the first things you should look at when assessing your past year’s training. Every runner prefers a satisfying peak-race performance to a disappointing one, but the silver lining around disappointing peak-race performances is that they provide better learning opportunities.

Sometimes a disappointing peak-race performance results from unrealistic expectations, but this scenario is much more likely to affect inexperienced runners than experienced ones. Perhaps the most common cause of failure to meet realistic expectations in a peak race is peaking too early. Runners often spend too much time doing specific, high-level training before a peak race and consequently do their best running several weeks early. If you feel you were running better a month or so before a peak race than you did in the race itself, and you did in fact sustain high-level, race-specific training for some time before the race, then consider modifying next year’s training in ways that will ensure that you don’t peak early again. Specifically, concentrate your peak-level training closer to the actual peak race. Extend your fundamental period of training so that you’ve achieved a higher level of general fitness when you begin doing hard, specific work.

In other cases, a disappointing peak-race performance results from the opposite cause. You fail to peak at all because you don’t allow enough time to build peak-level fitness and/ or you don’t do enough peak-level training before the race. If your training cycle leading up to a disappointing peak race was compressed or hurried, plan a longer training cycle next year. And if your training cycle did not culminate with at least four solid weeks of peak-level training featuring lots of challenging race-specific workouts, be sure that your next training plan includes a sharpening period that fits this description.

Another common cause of disappointing peak-race performance is failure to taper properly. Some runners race best when they engage in a modest taper, approaching the pre-race week as they would a normal recovery week. Other runners race best when they taper more drastically, starting their taper 10 days to two weeks before a peak race and reducing their training to a minimal level in the final week. If you feel that a poor taper might be the cause of a disappointing peak race in the past year, consider trying a different sort of taper next year. If your taper was short and modest, try a longer and/or sharper taper.

If your taper was fairly extreme, try doing a taper that’s more like a normal recovery week.

Sometimes a bad race is due to a bad taper, not necessarily bad training. © Alison Wade

How did I perform in my tune-up races?

After assessing last year’s peak-race performances, assess your tune-up race performances. Runners often perform better in tune-up races than they do in peak races. This phenomenon may indicate that the runner peaked too early and should modify his or her future training to avoid a repetition of this scenario.

It’s also common for runners to perform very poorly in tune-up races that fall early in the training cycle and to run steadily better in subsequent races. While this pattern does suggest that the runner’s training was effective, it usually also indicates that the runner started the training cycle at a relatively low fitness level and that much of the training cycle was wasted on playing catch-up. As I suggested above, I believe it is important to sustain a high level of base fitness year-round, so that when you begin formal training for a peak race you don’t have to play catch-up and can instead train in a way that builds on your solid foundation and takes your running performance to new heights.

If a tendency to get out of shape between training cycles is the probable explanation for poor performance in your early tune-up races, try to plan next year’s training in a way that enables you to stay consistently fit and start each training cycle at a higher level.

Did my running volume hold me back in any way?

After assessing your race performances, next look back over your training logs and consider the volume of running you did over the past year. Estimate your average weekly running mileage, determine your peak weekly running mileage, and note the size of volume fluctuations throughout the year. Now try to establish a cause-and-effect relationship between these volume numbers and the fitness development and race results you achieved in the past year.

Ask yourself the following questions: Could my body have handled more mileage than I took on last year? If so, is it likely that running slightly more miles would have improved my fitness and performance? In other words, was I held back by inadequate running volume? Or did I try to run too much last year? Would I have performed better in my key workouts if I had run slightly less in other workouts? Was I frequently fatigued or injured due to excessive mileage?

In answering these questions, bear in mind that problems that seem to result from excessive training volume are often caused by excessive fluctuations in running mileage. Injuries and overtraining fatigue tend to develop during periods of increasing running volume. If you allow your running volume to fall too low at one or more times during a running season, you have to devote more time to the process of making relatively larger volume increases when you begin focused preparation for a peak race. As a result you’re likelier to run more miles than your body is prepared to handle. If you experienced large fluctuations in your training volume last year, concentrate on making your running volume more consistent next year. If you do, you’ll probably find that the peak running volume that seemed to be too much last year is easily handled and more productive this time around.

Was my training poorly balanced?

Most runners are also held back by the quality of running they do as much as they are by the quantity of running they do. Specifically, their training lacks balance. Every competitive road racer should consistently include the following training stimuli in his or her training: easy runs, long runs, threshold runs, specific-endurance intervals, speed intervals, and maximal efforts (e.g., short hill sprints). The majority of your weekly running should be done at lower intensities, and only a tiny fraction should be done at maximal intensity, but no training stimulus should ever be overemphasized or marginalized. Very few nonelite runners train with appropriate balance. Improving the balance of your training stimuli is a simple way to improve your running without training more, or even harder, necessarily.

Was I limited by my aerobic fitness?

A “performance limiter” is a relative weakness in your running fitness that is the primary factor preventing you from performing better at any given time. If your aerobic fitness is underdeveloped relative to your neuromuscular fitness and specific endurance, then aerobic fitness will be your limiter. If your neuromuscular fitness is lagging behind your aerobic fitness and specific endurance, then neuromuscular fitness will place a ceiling on your running performance. And if your specific endurance is weaker than your aerobic fitness and neuromuscular fitness, then your specific endurance will hinder your overall fitness development.

A sure way to improve your running next year is to analyze your past year of running, identify your primary limiter, and find ways to address it in next year’s training. Start with aerobic fitness. There are several possible signs that you were limited by your aerobic fitness in the past year. The first is a tendency to perform better in shorter races than in longer races. Another sign of lagging aerobic fitness is a trend of stronger performance in shorter, faster workouts than in longer, slower workouts. Did you tend to feel substantially stronger running intervals at 1,500-meter to 3K pace than you did running threshold workouts at 10K to half-marathon pace? If so, then aerobic fitness was probably your Achilles’ heel. Poor recovery between workouts may also indicate relatively low aerobic fitness.

There are three ways to address limiting aerobic fitness in planning next year’s training. First, you can increase your overall running volume by adding one or more additional easy runs to your weekly schedule or by slightly increasing the average distance of your easy runs. This option is most appropriate for less experienced runners who have run low mileage in the past and feel ready and willing to run more. A second option is to increase the average intensity of your aerobic training by adding more threshold work to your schedule, tacking faster progressions onto the end of some easy runs, and incorporating faster running into your long runs. This is a good option for runners with at least a couple of years of training experience in their legs who are limited in their ability or willingness to increase their running volume. Finally, you can boost your aerobic fitness by doing longer long runs next year. I consider this option a good one for any runner who was limited by his or her aerobic fitness and is not already doing the longest long runs that are sensible with respect to his or her peak-race distance.

Was I limited by my neuromuscular fitness?

There are three major signs that you lacked adequate neuromuscular fitness in the past year. The first two are more or less the opposite of the first two signs of inadequate aerobic fitness mentioned above. If you tended to perform best in your longest races and worst in your shortest ones, and/or if you tended to feel stronger in longer, slower workouts than you did in shorter, faster workouts, your neuromuscular fitness was probably a limiter. A third indicator of limiting neuromuscular fitness is injuries or problems with muscle and tendon soreness.

The best way to address limiting neuromuscular fitness in planning next year’s training depends on precisely how it limited you last year. If you feel that you simply lacked adequate speed and power, add more hill sprints and more interval work at 1,500-meter to 3K pace to your training. This doesn’t necessarily mean you have to do a greater total amount of speed and power training in the early fundamental period, when this type of training receives its greatest emphasis. It might just mean that you train for speed and power more consistently throughout the training cycle by introducing it earlier and by not deemphasizing it as much in the later stages of the training cycle.

If you feel that you lacked strength more than you lacked raw sprint speed and power, the best response is to add some additional uphill running to your training next year. Specifically, run more hill repetitions, especially at the beginning of the fundamental period. In the remainder of the training cycle, transfer some of the interval work you would normally do on level ground to hills.

Hills are also my prescription to correct problems with injuries and soreness. If you had these problems last year, increase your commitment to steep hill sprints next year by doing more total sprints each week and by doing them more consistently throughout the training cycle. This will enhance the strength of your running muscles and connective tissues, making them more injury-resistant. You might also benefit from transferring some of the interval work you would normally perform on level ground to hills. This will allow you to build speed with less stress on the legs.

Was I limited by my specific endurance?

If your aerobic or neuromuscular fitness level is lower than it should be, your specific-endurance fitness will suffer as well, because specific endurance is nothing more than a goal-specific combination of aerobic and neuromuscular fitness. But it is possible to have well-developed aerobic and neuromuscular fitness and still be limited by your specific endurance. This problem results from a failure to combine your aerobic and neuromuscular fitness in the appropriate way for your peak-race distance and goal time.

Suppose you’re training for a 10K peak race. Your training program includes a fairly high volume of easy running, weekly long runs, and healthy doses of hill sprints and short intervals at 1,500-meter to 3K pace. But it does not include threshold runs or 10K-pace intervals—the workouts that are most specific to 10K racing. In this case you will reach a level of fitness that enables you to perform very well in your hill sprints, short intervals, and long runs, and you will probably run a decent 10K, too. But you will not perform as well in your peak race as you would if you included more specific-endurance work in your training.

If you had a disappointing peak race last year despite performing well in your speed work and long runs during the latter weeks of training, then you were most likely limited by your specific endurance. The same diagnosis can be made if you tended to feel stronger in workouts in which you ran substantially faster or slower than race pace than you did in workouts run at or near race pace. And if you simply did not do much race-pace running last year, you can be sure you were limited by your specific endurance even in the absence of other signs.

The cure for a diagnosis of limiting specific endurance is obvious. Do more specific-endurance training next year! Be sure to introduce a small amount of specific-endurance work, in the form of fartlek intervals and/or progressions (depending on your peak-race distance), at the beginning of the training cycle. Gradually increase the amount of specific-endurance training throughout the training cycle. In the sharpening period, all three of your weekly hard workouts should be highly race-specific.

Experimentation

Everything you do in training is an experiment, and it should all be viewed as such. You never know exactly how your body will respond to any specific workout or training pattern. Your expectations for how your body will respond are nothing more than a hypothesis. When your body’s actual response to training differs from your expectations, you must revise your hypothesis and tweak your future training accordingly. Too often, runners hang on to their hypotheses concerning the workouts and training patterns that ought to work best for them even after their application disproves them. Don’t make this mistake! When a given training practice does not work as well as expected, try a new one.

There is, of course, a converse aspect to this principle. When a given training practice does work for you, it’s important that you retain it. But competitive runners are much more likely to retain familiar practices that don’t work than to discard proven practices that do.

The fact that a certain training practice appears to give you good results does not mean that an alternative practice might not give you even better results, however. For this reason, I recommend that you stay open to experimentation even when you feel that everything in your training is working. There is no such thing as perfect training. The concept of perfection implies permanence and stasis. But in the process of training for distance running, your body is constantly changing. Consequently, training patterns that seem perfect for you now will no longer be perfect for you next year, or even next month. If you train exactly the same way next year or next month, you will not improve as much as you would if you took account of changes in your running fitness and modified your training appropriately.

I am not talking about drastic changes. Once you have begun to practice adaptive running, there will be no more need for drastic changes in your training. But there are plenty of minor changes you can make that will have a measurable impact on your progress as a runner. These minor changes are mainly to be found at the level of workout formats. There is a whole universe of specific workout formats out there. This book contains only a fraction of them. I encourage you to continuously learn about other workouts and try those that are compatible with the adaptive running system and seem to offer some potential to improve your performance.

I try new workouts on my runners all the time. Recently I borrowed a new workout from Nic Bideau, who coaches the Australian runner Craig Mottram. The workout starts (following a warm-up, of course) with six laps around the track. The first lap is typically run at 10K pace or slightly slower. Each subsequent lap is a little faster. The sixth lap is run at 3K to 1,500-meter pace. The runner then jogs a lap and completes a set of eight 200-meter intervals at 5K to 3K pace with 100-meter active recoveries after each. This entire sequence is then repeated. (If you choose to try this workout, you will probably want to complete the sequence just one time.) I like this workout because it allows my runners to perform a fairly large amount of work in a way that is not too taxing. Also, it can be adjusted for use at any point in the training cycle through manipulation of the pace targets.

It’s best to experiment in a controlled way. I don’t recommend trying new workouts too frequently or testing multiple new workouts simultaneously. As important as adaptability is in training, structure is also important. The single most important characteristic of a training cycle is direction. It has to move consistently in the direction of race-specific fitness. It’s very difficult to ensure that your training is doing this if you are constantly changing things. To ensure that they are truly building on each other, your workouts must maintain a “family resemblance” throughout the training process, changing only within certain strict parameters. Once you’ve settled on the types of workouts you plan to do in your next training cycle, it’s best to stick with them, modifying only the details based on how your body responds. Thus, the best time to select new workouts to try is between training cycles, when you’re planning and have not yet started the next ramp-up toward a peak race.

Setting Higher Goals

Suppose I challenged you to run as far as you could at a certain pace. My instructions were to hang on at the designated pace until you were so exhausted that you could not take another single stride without slowing down. Now let’s suppose you were able to run 13.91 miles at this pace before throwing in the towel. Knowing this, I could almost guarantee that if I had challenged you not to run as far as you could at that pace, but to run 14 miles at the same pace, you could have done it, because that objective goal would have motivated you to push through a little more suffering than you believed you could overcome without the goal.

This little thought experiment is intended to make the point that it is impossible to produce a truly maximal race effort without chasing some type of goal, whether it’s beating another runner to the finish line or beating a personal best time for the distance. You might think you’re running as hard as you can when you race without any particular goal established, but you’re not. It’s an unalterable reality of how the mind affects the body during running.

Naturally, the mind can overcome only so much matter. You cannot achieve just any goal simply by setting it. Going back to the thought experiment described above, if I had challenged you to run 15 miles at the designated pace, knowing that you could only run 13.91 miles without a goal, chances are very slim that you could have run an extra 1.09 miles without slowing down. An appropriate goal challenges you to push just a little bit harder than you otherwise would—to squeeze the last 1 percent of reserve that your mind allows your body to hold back without such a demand.

Past race performances provide the best information to use in setting appropriate future race goals. In most cases, next year’s goal time for a given race distance should be slightly faster than the best time you achieved for that distance last year. Accumulating fitness and better training will render your body able to perform at a higher level next year, but you might not fully realize the potential of these changes unless you set goals that demand it. In other words, on top of everything else discussed in this chapter, improvement requires that you aim for improvement. When setting goals for next year, try to account for not only accumulating fitness and better training, but also for the need to reach higher in your mind so that your body can follow.

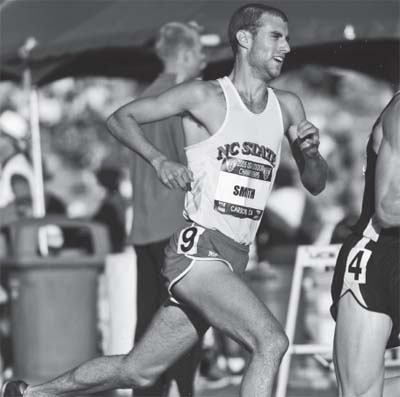

Andy Smith © Courtesy of the New York Road Runners

Runner Profile: Andy Smith

A lot of the runners I coach come to me as hard-luck cases—athletes whose careers have been stymied by frequent or major injury setbacks. Andy Smith might be the greatest hard-luck case of all. A 2005 graduate of North Carolina State University, Andy had only been able to run one race in two years due to injuries that culminated in surgery for compartment syndrome.

My work with Andy began with post-surgery rehabilitation in the early spring of 2007. My primary goal was to gradually and steadily increase his running volume to the point at which he was running twice a day and at least 100 miles per week. I was confident that by cautiously transforming Andy into a high-mileage runner I could greatly increase his durability and resilience.

In college, Andy had trained on the Lydiard system, which is characterized by lots of hard aerobic runs and very distinct training phases. I had him reduce the intensity of his aerobic running so that he could handle a much greater volume of such running, which was necessary to stimulate further aerobic development. Also, as I do with every runner, I made Andy’s training more consistently well rounded, introducing hill sprints and small amounts of specific-endurance work as soon after his surgery as I felt it was safe to do so and steadily increasing the balance of his training from there.

Andy’s primary event is the 3,000-meter steeplechase. Just eight weeks after his surgery, Andy ran an 8:34 steeplechase—just five seconds off his personal best time from college. Two weeks later he posted a personal best time of 13:38 for 5,000 meters. The future looks bright for this former hard-luck case.