CHAPTER ONE Beaten Down by Being Normal

Kim, a woman in her midthirties, consulted with me to discuss her health and how she might improve it. Like so many mothers, her daily schedule was hectic, as she juggled part-time work with family and household demands. Prioritizing helping her children and husband in the morning, she gave little thought to her own breakfast and lunch, and then battled to fit what was effectively a full-time job into her part-time day. Even as we sat down to focus on Kim’s own needs, her phone beeped and buzzed with seemingly endless messages from work, her husband, and reminders about events for the kids.

Kim’s evenings mirrored her mornings. Dinner needed to be cooked, and the kids wrangled for homework, dinner, and, eventually, bed. If she did manage to get the kids settled and asleep at a reasonable time, she usually spent the remainder of her nights on the couch, engaged in a vague and shifting combination of television watching, messaging friends on her phone, scrolling through Facebook, answering work-related emails, or “window shopping” for items she didn’t really need. Her husband sometimes sat with her, engaged in similar activities of his own, but more often lingered on his computer elsewhere in the house catching up on his own work.

Kim thought of the relationships in her life as “good,” but not great. She and her husband both felt committed to their marriage and tried to schedule some sort of a “date night” once a week, although the kids and their general lack of energy and enthusiasm often undermined that plan. Struggling to meet everyday demands, Kim and her husband didn’t connect deeply with each other much. Their sex life was mediocre, mostly because neither of them felt particularly energetic in the evening once the kids had finally settled into bed, and because they were essentially in survival mode much of the time.

Their relationship with the kids, like their relationship with each other, was not terrible, but not great, either. They faithfully attended parent-teacher conferences and looked after their kids’ academic needs and social lives, but they weren’t truly connecting. Case in point: Kim and her husband made it a priority to eat dinner most nights together as a family, but found it was such a battle to get the kids off their electronic devices that they eventually abandoned their no devices at dinner policy altogether. It just wasn’t worth the arguments and stress it caused everyone.

Physically, Kim wasn’t in terrible shape, but she’d lost the healthy, glowing “athlete’s body” she had maintained earlier in life. As she told me, she suffered from “the usual” back and knee aches, tension headaches, and her main concern, crashing energy levels. She felt physically and emotionally “fragile,” she said, and believed the answer (and her reason for seeking my advice) was to go to the gym three times per week and start exercising. She imagined doing some cardio on the bike and treadmill. When I inquired as to when she might fit this in, she said she thought she could do it over the winter months, after 8:30 p.m., once the kids were settled in bed. Kim was looking for help, but her perceptions about where to begin shifting were mismatched to what was actually causing her deteriorating physical and mental health. She was confused and discouraged but still trying to make things better, hence her consultation with me.

Does Kim’s story sound familiar? It should. Although “Kim” isn’t a real person, her story echoes hundreds of others I’ve heard throughout my years of coaching. Like her, most of us feel less healthy than we’d like—tired, overwhelmed, distracted, “fragile,” mired in uninspiring relationships. We want to fix things, so we try diets and exercise regimens and meditation, but nothing seems to work—or at least, not for very long, and not in the comprehensive way that we were hoping for.

Kim’s is the all-too-common story of the daily grind of modern life—where every day of the year, for years on end, is virtually the same. Modern life, in modern consumer cultures at least, has flattened out, averaged, or disregarded many of the oscillations, rhythms, and cycles of the natural world (and our evolutionary past). Sunrise might vary by three or more hours between summer and winter solstices, but your alarm still goes off at 5:15 every morning as regularly as clockwork. Seasonal temperature variations have been replaced with climate control systems in our homes, cars, and workplaces. No matter where you are, or what season you are in, it is always 65 to 72°F (18 to 22°C). If you fancy mangoes in the midst of winter, no problem. Pre-ripened picking, packing, and global shipping can bring you any tropical fruit your sweet tastes desire, even when it is literally freezing outside. And you can go to your gym and run on the treadmill under fluorescent lights at nearly any time of the day or night.

It feels great to have the food we like continuously available and to not experience temperature extremes, but this modern “flattening” also has a serious downside. As with Kim, it’s left us “stuck” in a mix of incongruent health behavior, like maintaining hectic summer-style schedules in the depths of winter. The good news is, our natural rhythms haven’t been lost. They’re still there, temporarily buried but surprisingly accessible, waiting to be rediscovered and to direct you toward a more natural and effortless way of being in the world.

Our Bodies, Our Rhythms

Let’s say I plucked you and a group of your closest friends and loved ones out of our standardized, modern existence and dropped you all on a Jurassic Park–style island (we’ll say sans dinosaurs for now). You have no access to any of life’s modern conveniences, and in particular, no access to clocks, watches, calendars, or any other modern way of marking time. How would you keep track of the passing days?

Chances are, within a very short period of time—quite literally, hours—you would hook back into one of life’s many natural rhythms. In the absence of bright lights, Netflix, smartphones, and so on, you and your island clan would likely head to bed not long after sundown, with nothing to wind you up except for the occasional brightness of a full moon. You would quickly learn to mark the progression of the days via the sun’s rising and setting. You might track the progression of the year by following the sun’s arc in the sky—low in winter, high in summer. In this way, you would soon be able to mark the solstices—the point at which the sun changes its trajectory and the days become shorter or longer, cooler or warmer. Approximately halfway between the solstices, you’d have an equinox, where day and night are roughly equal in length. You would also track the months and progression of the year via the repeating phases of the moon—the lunar cycles. You might notice changes in plant life, flowers and fruit, weather patterns, and animal behaviors as indications of changes in the seasons. The longer you remained isolated from modernity, the more likely you would be in tune with, and live by, such rhythms.

Within yourself, in the absence of caffeine, sugar, alcohol, artificial light, and all the other common stimulants we use to get through life, you might begin to notice a certain rhythmicity to your own energy levels. You might become spontaneously active and exploratory in the early part of the day but seek a comfortable spot to take a siesta in the early afternoon. You might perk up again in the late afternoon and into the early evening but find yourself wanting to head to sleep not that long after sundown, and certainly much earlier than you would in your modern, electronic home. Spring and summer might find you and your tribe using the longer day length and warmth to explore your surroundings further, attempting to learn what was over that mountain, or beyond the horizon. Autumn and winter might see you lingering a little closer to your base camp, hunkering down on the shorter, cooler days, and making the most of the bounty of resources you had stockpiled during the warmer months. Winter would mean less exploration and activity, and more recovery and planning ahead.

Year upon year, you’d see these rhythms organically ebb and flow, expand and contract. If you experienced your particular environment long enough, you might begin to notice rhythms in longer time frames, such as climate rhythms—how every five years or so, for example, it might become particularly wet or dry. Some plant or animal might become abundant or scarce on a rhythmic basis. Perhaps within your own lifetime, or across the generations, you would accumulate a store of such environmental knowledge and wisdom, and be capable of predicting the frequency of volcanic eruptions, earthquakes, and other natural occurrences. These are just a few examples of some of the many rhythms, short and long, that exist in the natural world and that our ancestors (and thus our own genetic, social, and cultural heritage) would have had exposure to for countless generations. This accumulated wisdom depends on intergenerational respect and the recognition of the value of elders as guardians of invaluable information that cannot be neatly packaged into Wikipedia articles or tweets.

But of course, we don’t live in Jurassic Park—and we don’t need to in order to sense our natural patterns. Even in the pressure cooker of modern life, they peek through from time to time. When we get restful sleep at night, wake up energized, get into a groove sometime midmorning, and tap into our best productivity, we notice it. We might also notice energy fluctuations throughout the year. Some months we might have boundless energy, while in others we might feel quieter and more contemplative.

Taking such observations seriously and studying our bodily patterns, we find that we aren’t just peripherally bound to the ebb and flow of the natural world. Rather, those oscillations are inscribed into our very physiology. We can think of a biological rhythm as any cyclical change in the body’s chemistry and/or function. That broad definition includes everything from our daily sleep cycles, to the regulation of our body temperature, to the menstrual cycle. To use the technical lingo, these rhythms are endogenous—controlled by an internal and self-sustaining biological clock.

Body temperature is a good example. You might remember from high school health class that our “natural” temperature is 98.6°F. But that’s just a baseline, as our body temperature fluctuates throughout the day. During our waking hours, it gradually rises several degrees, hitting its highest point around 4:00 to 6:00 p.m. The body’s lowest temperature comes in the early morning, hours before we wake up.1 That’s useful to know, as we feel our most energetic as our body temperature increases throughout the day, and we feel more relaxed and sleepy as our temperature falls in the evening and nighttime.2

Decreasing temperatures signal to your body that it’s time to slow down and prepare for sleep. We sleep in cycles, too, all of which are roughly ninety minutes long. When we enter our most intensive, rapid-eye-movement (REM) periods of our sleep, the cells controlling our temperature temporarily deactivate.3 That means our surroundings determine our body temperature during REM. If you’re missing some needed shut-eye, or if you wake up frequently at night, it might be that your bedroom is too warm.4 Consider lowering the thermostat a few degrees. Or, better yet, ditch those pajamas and sleep au natural. Unfortunately, modern environmental exposures, as well as stress and anxiety, can influence and disrupt these endogenous rhythms as well.

In addition to internal, self-activating cues, our bodies also have external or exogenous rhythms, biological cycles that harmonize with external stimuli. Such external stimuli are referred to as zeitgebers, from the German word meaning “time givers.” Zeitgebers help to keep the biological clock synchronized to a twenty-four-hour period and include environmental time prompts such as sunlight, food, noise, and, important for us as social animals, interaction with others.5 For instance, your internal sleep/wakefulness cycles are synchronized with the external light exposures of day/night. Get too much light at the wrong time, and you’ll have problems. We’ve all heard that we should avoid screen time before bed, and it’s not to ruin our fun. Light directly interferes with our sleep, and research suggests that such late-night exposure might be linked to cancer, obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular problems.6

Dr. Wendy Troxel, a senior behavioral and social scientist at the RAND Corporation, contends that partnered sleeping can help the body release zeitgebers and keep us in healthy rhythms. “Partners can be very helpful to help enforce consistent sleep and wake routines,” she said. “It becomes a reminder to go to bed instead of staying up late playing video games or binging on Netflix.”7 Though Dr. Troxel concedes that many studies associate sleeping alone with a better night’s sleep, those same studies reveal that people strongly prefer social sleeping. “Prioritize sleep as a couple. Think of it as an investment in your relationship, because you really are a better partner as well as more productive and healthier and happier when you sleep better,” Dr. Troxel said.8 Whether we opt for social or solitary sleep, we must ultimately curtail our late-night light exposure and develop other healthy sleep hygiene practices to keep our internal cycles harmonious.

You’ve probably heard of circadian rhythms, a Latin word meaning “about a day,” which refers to our bodies’ core endogenous rhythm. This twenty-four-hour internal clock is the same as the time it takes for the earth to rotate on its axis—a rhythm so fundamental that it has made its way into our genetic codes.9 Your circadian rhythm coexists and moves in harmony with many (if not most) physiological and behavioral processes that occur, cyclically, every day of your life. These include your sleep/wake cycles, levels of alertness, body temperature fluctuations, blood pressure variations, reaction times, hormone secretions, digestion, and bowel movements.10

On a local level, many of these functions themselves run on shorter, recurring ultradian rhythms. Think of sleep, which happens in approximately ninety-minute cycles throughout the night. As it turns out, ultradian cycles of around ninety minutes operate during the daytime too.11 Most of us can’t maintain optimal productivity for over ninety minutes at a time, as our energy and creativity naturally ebb after such sustained focus. Instead of another cup of coffee, or disciplining yourself to keep your “nose to the grindstone,” try taking a break after every hour and a half of work.12 You might find yourself refreshed and recharged, ready for another ninety minutes of focused work.

Digestion, appetite, blinking, and sexual arousal also run on shorter rhythms. Some of these processes happen with precision and regularity. Others, like our hunger or the cycles of our moods, are more mysterious. Either way, these automatic processes tend to fade into the background as we go about our lives. We don’t pay any real attention to them until they become disrupted in some way. And then, as we’ll see, we frequently are forced to pay a lot of attention.

The Neuroscience of Rhythms

Have you heard about a “master clock” in humans and other mammals that helps to govern our rhythms and biological processes? It isn’t simply a metaphor, but a real place in the brain’s hypothalamus, located in a cluster of about twenty thousand nerve cells known as the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN). Situated right above the optic nerve, the SCN is sensitive to external stimuli, which help it keep accurate “time.”13

In the absence of external zeitgebers, this master clock maintains a free-running rhythm of between twenty-four and twenty-five hours—your intrinsic circadian rhythm.14 Because the shift from dark to light/light to dark happens twice per day, this synchronized rhythm is also called the diurnal rhythm. We synchronize ourselves to the daily rotation (rhythm) of the planet in step with our diurnal rhythms. But as I’ll discuss later in the book, the way we behave in the modern world often disconnects us from this planetary synchrony. The diurnal rhythm becomes disrupted if our SCN receives a light signal when it is expecting darkness, or darkness when it is expecting light. We all know what it’s like to feel groggy after a long flight—our diurnal rhythms are out of sync, and in conflict with external stimuli.15 People who habitually reverse their natural diurnal habits, by working the night shift, for example, also experience disruptions in sleep and, as we’ll see, are even more vulnerable to chronic diseases.16

You might have heard about the hormone melatonin and wonder how it fits into this rhythmic mix. When night falls, and our SCN no longer senses light, it signals the pineal gland to produce and release melatonin. As this hormone gets into the bloodstream, we become less alert, and the idea of sleep becomes much more enticing.17 We’ve all been there! Melatonin is classically thought of as a sleep hormone, but as you will read later, it is perhaps best thought of as the darkness hormone. Our bodies release it in the absence of light, and for most of us, sleep happens to occur during this time.18 You’ve likely seen it advertised in grocery market aisles and on Amazon—it’s the only hormone authorized for sale without the need for a doctor’s prescription.19 Since melatonin is linked to the dark of night, the longer the night lasts—as it does through fall and winter—the longer our exposure to melatonin. Conversely, the long days and relative short nights of spring and summer shorten the duration of melatonin output released at night. (Unless, of course, we’re popping the melatonin we’ve purchased from the pharmacy like they’re breath mints!)

Melatonin, then, is the chemical messenger that links the expanding and contracting cycles of light in our external environment to our own master clock. Melatonin plays a role, for example, in synchronizing digestive secretions and enzyme pulses, as well as periods of immune system activity. Even your skin has its own diurnal rhythm, exhibiting greater resilience to UV radiation early in the day.20 Melatonin allows the brain to orchestrate our seasonal rhythms and the biological processes that are best synchronized with these rhythms.21 But when we expose ourselves to light at night, even in small amounts, melatonin production declines and all these processes become unaligned. Yes, that means that creature comforts like a night-light, and the innocent-looking light emissions from our electronics and consumer appliances, might be imperiling our sleep—and, by extension, our health. Small things can make big differences.

A Seasonal Model of Health

Our biological rhythms and the mechanisms by which they operate can become fairly complex when you get deeper into it—I’ve only just scratched the surface. But these rhythms become simpler, more intuitive, and more useful from the perspective of personal health when we look at them experientially and behaviorally, and in terms of the key hormones in our brains that help shape our experiences and behaviors. In the core areas of how we sleep, eat, move, and interact, we can break our experiences of sleep, food, movement, and social contact down into four conceptual blocks or seasons that occur throughout the year—spring, summer, fall, and winter. As a prelude to the rest of the book, let’s take a quick look at each of these seasons in turn.

We start with spring. Within the context of the annual seasons, spring is the moment we start to become more physical, awakening from the slumber of winter. The coming of spring signals rebirth and reincarnation, which some people mark in religious traditions like Easter, and others in the annual “spring-cleaning” ritual of sprucing up the house. Many of us are titillated with the coming of spring, anticipating the fun and energy of summer that soon awaits.

Some of this titillation likely derives from spring’s food offerings. In spring, there are fewer root vegetables and squashes left over from last fall, and the earth produces more fresh, fast-growing vegetables, like leafy greens. When I think of a hormone that best typifies this season, I think of dopamine. Please understand: I’m not making a physiological argument about hormone thresholds correlated to each season. Instead, I’ve come to think of our calendar seasons as having personality traits and characteristics. Certain neurotransmitters and hormones, which are constantly coursing through our bodies, typify or embody essential elements of the different seasons in fascinating and sometimes uncanny ways. Take spring’s dopamine. From a neurochemical standpoint, dopamine signals spring in that it triggers or motivates us to take risks, seek novelty, explore, become curious. Technically speaking, dopamine is a neurotransmitter, as it’s released by brain cells called neurons. Dopamine, of course, is infamous for its role in reward, pleasure, emotional regulation, and addiction. Springtime is essentially the season of dopamine, and there’s nothing wrong with that.

When it comes to seasons, spring and summer are thematically connected. They are both, broadly speaking, outward-looking, expansive, productive seasons. After we’re done cleaning our houses, we’re inclined to explore and meet new people and go new places in the spring, something that expands and intensifies during the months of summer parties and neighborhood barbecues. As spring develops into summer, our bodies crave more carbohydrate-rich, energy-dense foods. Sugary fruits are naturally plentiful during this period, and our ancestors gorged on them whenever possible. When I think of summer, the hormone that immediately comes to mind is adrenaline, a hormone that’s well known for its role in responding to perceived stress. Adrenaline is useful because it helps us to focus and perform under that stress. And get this: adrenaline is biochemically made from dopamine.22 Dopamine, which gets us jazzed about things to come, is biochemically converted into adrenaline, which helps us perform well and conquer the stressful challenge, however we might define these terms. I find it fascinating and even profound that the symbolic theme for spring (dopamine) is biochemically converted into the symbolic theme for summer (adrenaline). For our ancestors, performing might mean going into battle against a neighboring tribe or hungry predator. For modern man, it might mean summoning the courage to open your business or propose to your long-term partner. Either way, adrenaline is about action and engagement, and summer is all about performance and its subsequent stress.

During the summer, adrenaline courses throughout our bodies because we live in an extended period of stress—all of those late nights, all that stimulation, all the things to do, all that hard work. At this point, you might be thinking, “Hang on, Dallas. Summer is about relaxation and the beach. It’s not stressful.” I’m not talking about stress in a negative, psychological sense. I simply mean demands placed on the body and mind that require cognitive and metabolic resources. No doubt, dopamine and adrenaline both feel good. We even call thrill seekers “adrenaline junkies,” a reference to the addictive properties of these endogenous substances. In fact, stress hormones and endorphins (natural painkillers), and all of the experiential hallmarks of spring and summer, feel so good that we have trouble moving away from them, even when it’s no longer summertime. When we become hyperstimulated and overloaded, then we experience stress in a more negative and costly way. We become stressed out in the popular sense of being overtaxed, frayed, depleted.

The seasonal pivot from summer to fall is crucial and difficult to make. During the fall, fresh fruit supplies naturally dwindle, and the earth produces lower-sugar, starchy root vegetables. With cooler weather and shorter days, we tend to gravitate to heartier, meatier comfort foods. The Thanksgiving table is an ideal representation of what the fall diet is all about. A complete protein is the meal’s centerpiece (the turkey), accompanied by hearty, satiating vegetables like mashed potatoes. There isn’t typically kale salad with strawberries and feta cheese at the Thanksgiving table, unless you’re trying to placate your vegetarian aunt from California. Tender greens and berries are spring fare, and at the Thanksgiving table they would seem out of place, as our bodies at this time of year naturally crave more protein and naturally occurring fats, with less emphasis placed on consuming sugar.

Now if what I said about kale salad in fall was hard to hear, prepare yourself because it gets even harder: this is a normal time to gain a little bit of weight. Think again of the stereotypical overeating we often see at Thanksgiving. It’s conceptually consistent with the spirit of this transitional season, as our bodies are biologically saying, “I have to eat a bunch of calories because the cold winter is coming, and I really should prepare with putting on some extra body fat.” This modest, seasonal weight gain isn’t abnormal or at all damaging. The problem, once again, is when we get stuck in a certain mode and don’t graduate to a different phase that would naturally rebalance the preceding seasons. When I think of autumn, the neurotransmitter that comes to mind is serotonin. Serotonin is associated with reward and pleasure, as well as meaning and gratitude. It’s an adult version of adrenaline—it feels good, but still prompts us to think about the broader picture, about cooperating with others, and about the future. As I’ll explain in more detail in later chapters, serotonin is also associated with leadership, with contribution to the community, and with connectedness to others.

Just like spring and summer, the phases of fall and winter are conceptually related to one another. While, generally speaking, the spring-summer block is largely about moving fast, working hard, and looking out for ourselves, fall and winter are seasons of slowing down, reconnection, and increased intimacy and generosity with the people who matter the most to us. When the winter months arrive, the natural carbohydrate availability recedes even more, and we incline to more dietary fat (with complete protein staying as a pretty consistent feature across all the seasons). This corresponds with a natural reduction in overall physical activity during these cold months, especially those that require large amounts of dietary carbohydrates to support (think hard running or cycling). We all know what comes to mind when we think of winter foods: short ribs, hearty and warming stews, and soup, something that will warm and nourish us after being out in the cold.

When I think of the interpersonal warmth and closeness associated with winter, I think of the hormone oxytocin. Fall’s connectivity, characterized by serotonin, is a fitting precursor to the winter’s oxytocin, a critical neuropeptide (something neurons use to communicate among themselves) that’s crucial for strengthening deep and intimate bonds between people. Oxytocin is released during pregnancy, childbirth, and breastfeeding. It’s been stereotyped as the “love hormone” because it is released during intimate romantic and sexual encounters as well, and even during conversational eye contact, close physical proximity, and nonsexual touch. So it’s less the “love hormone” and more the “bonding hormone,” which allows the broad connectivity of fall to yield to the deeper intimacy, trust, and closeness of winter.

Stuck on Summer

What a beautiful cycle. Our social interactions, activity, sleep, and nutritional inputs harmonize elegantly with the passage of the seasons. But, you probably guessed it, there’s a problem. In the modern world, we’ve become like Kim: stuck on summer. By that I mean we become stuck in a world of (mostly) pleasurable stress. Summer, as we’ve seen, is a great time, both literally and metaphorically. It’s a period of long days and short nights, brimming with activity and stimulation. It’s when the neurochemical stimulation of hormones and neurotransmitters like dopamine lead us to gorge on sugary, carbohydrate-dense fruits. And that’s biologically normal … in the seasonal context.

But following our organization into sedentary civilizations after the agricultural revolution (ca. 10,000 BC), we gradually abandoned any seasonal oscillations, and have had a hard time making the annual pivot to fall-type behavior. Once we started cultivating grain and other agricultural plants, carbohydrate-rich foods became available all year long and eventually formed the backbone of our “civilized” diets. Following the industrial revolution a few hundred years ago, highly processed, high glycemic index, sugary foodstuffs became continually available as well. As I said, it’s normal for us to crave such foods when experiencing the stress of summer. Those cravings are appropriate responses to short-term stressors. Unfortunately, many of us never switch out of summer mode, meaning we live for years or even decades preferring and actually building our entire food system around the carbohydrate-centered diet of summer.

Many of our modern ills arise from our entrenchment in a perpetual summer mode. Take sleep, for example. When we expose ourselves to artificial lights in our office buildings, fluorescent lights in grocery stores, and the blue wavelength lights (such as those emitted by our phone and computer screens) that potently disrupt our normal circadian rhythms, we give our brains the message that it’s daytime, and it’s summertime. The quantity and quality of our sleep both suffer, causing our bodies to crave quick energy in the form of carbohydrates. Yes, disrupted circadian rhythms contribute to sugar cravings. When we’re bathed in disruptive artificial light, especially after the sun has set, it becomes increasingly difficult to hear the deeply intuitive part of our bodies saying, “Hey, it’s wintertime, go for the nourishing beef stew instead of the soda and chocolate muffin you’re eyeing.”

And that drowning out of intuition and satiety signaling leads us directly to overeating and obesity. When our rhythmic ancestors overate sugary fruits and seasonal plants, displacing some dietary fats and complete animal protein sources, it made sense because seasonal summer stress made us neurochemically inclined to prefer energy-dense, sugary foods over complete, more deeply satiating dietary proteins and healthy fat sources. But whole foods containing complete proteins and fats aren’t just great to consume because they are nutrient dense—they are also the most satiating of the macronutrients, and as such they suppress our natural hunger signals more effectively than the same number of calories from carbohydrates. Overeating carbohydrate-laden foods, especially carbohydrates from refined, low-nutrient sources, year upon year, leads to the dysregulation of our appetites and metabolism, setting us up for more cravings and overconsumption. Our bodies become chronically inflamed, metabolically deranged, overweight, and chronically diseased as a result. A chronic summer diet causes chronic disease.

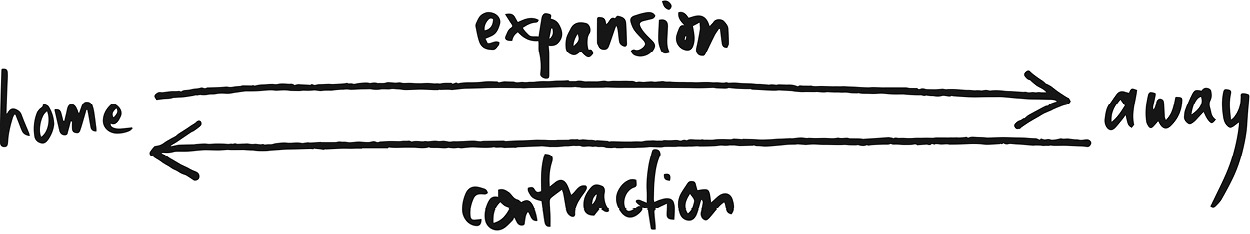

It’s easy to get there because, let’s face it, transitioning from summer to fall is hard. It’s tough to tear ourselves away from the fun and frenzy of the summer’s Las Vegas Strip and settle into autumn’s quiet cabin in the woods. This makes sense intuitively and neurochemically: expansion and excitement is so much more neurochemically motivating and rewarding than contraction and restfulness. In today’s world, summer is the expansive action phase, whereas the contraction phase requires more attentiveness and self-awareness to implement. In the natural world, it simply happens as a part of the whole cycle, but in today’s world, we need to deliberately reintroduce contraction phases, as well as reframe contraction as balancing, stabilizing, and healthy. When’s the last time you heard a positive news headline detailing how excited everyone was about a contracting stock market or smaller company earnings? Expansion is crucial. Think about what would have happened to our hunter-gatherer ancestors if they were not neurochemically motivated to explore, take risks, or seek novelty: they would have stayed in one safe and quiet place, depleted their resources, and probably starved to death. We needed the neurochemical motivation of dopamine and the performance enhancement of adrenaline to act, take risks, learn new things, explore the world … and survive. But problems arise when we don’t confine such action to the appropriate season, or when we don’t stop exploring. Like a seafaring explorer, we need to return home to port periodically, or else we’re simply perpetually lost at sea, running low on supplies and feeling disconnected from our roots.

Let’s not forget: while dopamine and adrenaline are pleasurable, they also cause us to become shortsighted and self-centered. They give us focus on the challenge or scenario at hand, but they also put blinders on us—blinders to other perspectives, other people, other ways of being. This is partly why drug addicts often lose track of practical aspects of their lives; they get hyperfocused on destructive neurochemical patterns. These neurochemical stimuli might feel amazing in the moment, but they don’t lead us to plan wisely for the future or reflect deeply on the past. They don’t facilitate broad, integrated thinking, or peaceful introspection. I don’t know about you, but being stuck in summer is exhausting too. Don’t you often feel like a lot of parents do at the end of the summer, wondering when the kids will go back to school so you can get a break? We often look forward to the fall for the shorter days, which mean earlier bedtimes. If that sounds familiar, you aren’t alone. Many of us, myself included, have the perpetual sense of being frazzled and run-down, but we tell ourselves that we can’t just stop in the middle of the madness (unless we get an illness, which is often the body’s way of saying, “Hey, I really need some more caring attention over here!”). The feeling of being overextended is one that many of us carry for years and decades. You might not even recognize it anymore because you’ve lived with late summer exhaustion for so long. But if that’s how you’re feeling, take note: that’s not okay. If it feels out of balance, that’s because it is.

Breaking Free of Summer—and Getting in Tune

Many of us can at least partially identify with Kim’s life—I know I have at various points in my life. Let’s say that I only had an hour to consult with her. This is how I’d begin our journey together. I’d introduce her to the simple concept of expansion and contraction, of seasonal change, and encourage her to begin to develop a rotating or oscillating mind-set. When it comes to her social interactions, I’d encourage her to think of ways she and her family could slow down and be present with one another at some moments, while still pursuing activity and stimulation at others. Kim needn’t do anything radical. She could start with simply spending more time with her kids, bracketing out some time to talk about everyone’s day, or maybe even suggest meditating as a family. The larger point for her and for all of us is to jump right in and start experimenting—and not just with restoring rhythmicity to our social interactions, but to our eating, movement, and sleep as well. It doesn’t matter where we begin. So long as we begin somewhere, we’ll gradually become more aware of our innate patterns, and how to honor them.

The summer-to-fall pivot is a confronting, surprising, and even counterintuitive transition. But as I’m going to suggest in this book, although we might like the stimulation and fun of summer, we might also feel a little hollow or empty inside from always being in this mode. As a result, nudging ourselves back little by little to some fall and winter behavior can prove to be healing and deeply satisfying. Kim, for example, probably doesn’t want to go to wine and cheese with the girls every week, because she’s exhausted. She might not want to attend all her children’s classmates’ birthday parties, although she might feel subtle pressure to do so. Sometimes we gravitate to larger social events and welcome the opportunity to attend or host grand occasions. But we can only know if this is what we really want, and not simply ingrained routine or social expectation, when we slow down and check in with our innermost desires. When we give ourselves permission to slow down, contract, and connect more meaningfully, intimately, and vulnerably with a smaller circle of loved ones, we usually experience a degree of relief from the perceived expectations to do everything all the time.

Our lives and our bodies can be so much healthier and more fulfilled if we slow down, settle in, and fully immerse ourselves in the restorative phase of fall. The summer lights will still be there, beckoning, next year. But for now, take a long-overdue opportunity to rest and recharge. Over the next four chapters, we’ll explore in more detail how we become stuck in summer in the four key domains of sleep, food, movement, and social interaction. We begin with an area that so many of us misunderstand and neglect in our 24/7, always-on, technologically saturated world: the need for an honest night’s rest.