CHAPTER FOUR Moving to the Rhythm

James was tired of working for the man in the daily nine-to-five office grind. He woke up early to catch the subway into the office and ended his days in much the same way. He could only make it to the gym after work, and while it made for a long day, it provided him a sorely needed stress release after being chained to a desk. James chafed under this weekly routine and dreamed of working for himself, building a robust online platform, and then cracking the big time as a social media influencer. As a self-employed entrepreneur, instead of a corporate shill, he figured he’d have more autonomy and flexibility—the freedom to do what he wanted, when he wanted, including hitting the gym whenever he liked and traveling to exotic places like all the “influencers” seemed to be doing all the time.

James eventually quit his job and began working for himself at home. He soon discovered that producing high-quality content for his channels and staying ahead of his competition wasn’t easy. To keep pace, he changed his routine dramatically. In order to post initial content before viewers scrolled their social media feeds at breakfast or on their daily commutes, James began getting up earlier in the morning. He also stayed up later and later so as to keep up on all the social interactions on his channels. In order to maximize those all-important likes and subscribes, he had to pay constant round-the-clock attention to his screens, leaving him only a few bleary hours of shut-eye every night.

After a few months of this new schedule, James saw a marked deterioration in his physical fitness and an increase in his body fat levels. As he realized, he had replaced a nine-to-five with a five-to-nine (if not worse), and was no longer walking twice a day to and from the subway. He seldom made it to the gym and was less focused when he did go, posting Instagram stories along the way. James had swapped working for the man with working for a computer algorithm, endlessly chasing hits, likes, subscribers, and comments. The algorithm was proving to be a much more demanding boss, and James was paying the price.

James’s story points us to a sad truth about technology. We now have labor-saving devices like computers in every home, constant connectivity throughout the world, and the ability to work from anywhere, largely according to our own schedules. But do we have more free time for physical activity as a result? Not at all. Instead, the industrial, technological, information, and social media revolutions have eroded the boundaries and blurred the lines between our professional and private lives, between home and away. Thanks to the powerful computer in our pockets, we are constantly connected to the office, and moving less than ever before, regardless of our occupation or industry.

We also increasingly spend what leisure time we do have in front of screens. American adults spend almost 50 percent of their days, or more than ten hours, with their noses buried in their tablets, smartphones, computers, and televisions.1 In 2016, American adults also logged nearly six and a half hours of sitting a day, probably looking at screens.2 Such sitting time is harmful—to quote a CNN headline, reporting on a 2017 Annals of Internal Medicine study, “Yes, sitting too long can kill you, even if you exercise.”3 Unfortunately, most adults don’t exercise either. As a 2018 World Health Organization (WHO) study found, only 25 percent of global adults engage in enough physical activity, which per the study left “more than 1.4 billion adults at risk of developing or exacerbating diseases linked to inactivity.”4

The situation is even bleaker for younger Americans. Of the five and a half hours of free time that American teens have each day, the Pew Research Center found they spent the majority (almost three hours on weekdays and nearly four hours on weekends) scrolling, swiping, surfing, and playing games on screens.5 Year after year, in tests assessing physical fitness and strength, children have become weaker and less aerobically fit. “Kids today are less fit than their parents were,” proclaimed the Washington Post in 2013, echoing many such headlines since. Citing a series of studies analyzing millions of children throughout the world, the article demonstrated that today’s kids had fitness levels significantly inferior to those of their parents.6 This was true across different genders and ages, and probably struck most as unsurprising. Schools have scaled back physical education programs, and participation in organized sports hasn’t generally increased over the years.7 Parents and educators tend to believe that maintaining optimal physical fitness, and understanding how one’s body works, isn’t as important for the future as, say, learning how to code or score high on a college entrance test. And this pervasive attitude directly harms our youth. According to Sam Kass, a former White House chef and head of Michelle Obama’s Let’s Move initiative, “We are currently facing the most sedentary generation of children in our history.”8

Everything from the removal of sidewalks (often to widen roads and allow better traffic flow), to fears for children’s safety, to increasing traffic on school routes has resulted in children walking and cycling less and being driven to school and extracurricular activities. Notice the irony. Anxious parents drive their tired and unfit children to school, increasing the traffic and pollution around schools while reinforcing their fears about the dangers of walking or biking. This in turn further deteriorates our kids’ physical fitness levels. It’s a vicious, sedentary cycle.

Previous generations of children and adolescents may have sought to get out of the house to hang out, in person, with their friends. For today’s kids, access to Wi-Fi is paramount, and with more and more children having their own smartphone at a young age, the constant connection these devices afford means kids are even less likely to leave home and move. According to the WHO, only 20 percent of global youth get enough exercise.9 In 2019, the WHO publicized new guidelines suggesting that “to grow up healthy, children need to sit less and play more.”10

All of us have to get ourselves moving—but how exactly? As I’ll discuss more later in the book, we must first establish a baseline pattern of movement in our lives—an “anchor,” as I call it—by reintroducing activities like easy walking, hiking, taking the stairs, and electing to carry our personal items. Once we recover a measure of the physical strength that our ancestors likely enjoyed, we can go on to optimize our health and longevity by slightly modifying our movements on a seasonal basis. As we’ll find, our renewed dedication to physical strength will increase our longevity and quality of life, leaving us with strong, resilient, and happy bodies over a long life span.

“Working Out,” Caveman Style

Did our distant ancestors really work out? Of course not. They didn’t need to, because in the course of their daily lives they engaged in a broad range of physical activities, like walking, carrying, lifting, and the occasional sprint to flee from a hostile predator or violent adversary. Based on what we know about our ancestors’ lifestyles, we might characterize their fundamental and basic movements as including the following three elements:

- They undertook a relatively high volume of lower-intensity, high-frequency activities such as walking, with much of it performed as incidental physical activity throughout the day. They simply moved.

- They loaded their muscles, bones, and connective tissues by engaging in lifting and carrying movements, beginning with body weight and progressively increasing the loads over time. They lifted and carried heavy things.

- They undertook a relatively low volume of high-intensity activity, such as sprinting, doing so after building a strong foundation with both lower-intensity and higher-loading (lifting and carrying) activities. They ran like hell occasionally.

Early on in my thinking, I transposed this three-part movement oscillation onto my seasonal model, arriving at broad generalizations about how our preindustrial human ancestors moved. Summer, with its longer days and warmer temperatures, lent itself to doing more work—gathering, hunting, child rearing, and resource exploration—all in preparation for the coming winter. The amount of activity was high, but its intensity remained low. Come winter, at least at high latitudes, the amount of activity decreased. It would have been too brutally cold to stay outside for very long, and the daylight hours too short to venture on long explorations. But with a need to gather food (predominantly from hunting), retrieve water (possibly frozen), and lug wood for the fire, the overall relative intensity of winter activity would still have been considerable.

While this is a convenient shorthand for my model, I now realize that life for our ancestors wasn’t this consistent or straightforward. Not every tribal society would have remained in one place across the year. Many tribes would have migrated, keeping pace with roaming herds and flocks, or ventured to more hospitable climes during winter. Many ancestral societies would see a mixture of the three main elements I’ve outlined: a lot of relatively low-intensity movement and a lot of lifting and carrying, punctuated by infrequent and intermittent bursts of high-intensity activity (once again: think running from a hostile lion). While the relative balance of these elements might have changed seasonally to a certain extent, I don’t believe the pendulum would have swung all that far. Indeed, of all my four keys, I now feel that movement and physical activity are perhaps the least oscillatory, relative to sleep, diet, and even social connection.

I’m not saying that varying our movement patterns is unimportant. Think of food. While we lack details about Paleo man and woman’s caloric expenditures and exercise routines, we do know that they were incredibly resilient, adaptable, and varied in their diets and movements—they were food and movement omnivores, so to speak. Humans are incredibly adaptable. For the sake of our health and well-being, we should strive to be so, too, engaging in nourishing movements like lifting and carrying that bolster our musculoskeletal and nervous systems, rendering us capable and durable. Ancestral movement patterns functioned atop a physical foundation of strength (lifting and carrying), with most movement occurring at a relatively low intensity (walking) but punctuated by relatively short bouts of high-intensity movement (sprinting). The totality of these ancestral movements resulted in what physical therapists and fitness practitioners now call excellent general physical preparation (GPP).

Within this general rootedness in broad-based movement, our ancestors likely varied their physical activities to some degree. Consider the evolutionary imperative of high-intensity physical activity. Our ancestors would have needed and utilized short bursts of speed and power in a variety of scenarios, ranging from the final lunge to make a kill to the fight-or-flight response from predators (including other humans). In our ancestral environments, you couldn’t out-jog tigers or flash floods. Short-burst activities would have oscillated on a semi-seasonal basis (think of hunting season versus migration season), strengthening our ancestors’ bodies and increasing their survival rates and vitality. They would have also improved certain metabolic pathways, making our ancestors better at converting carbohydrates into cellular energy, and helping them control and clear lactic acid from their muscles. When performing low-intensity, general physical activity, like migrating when the weather was bad or when following a herd of animals, our ancestors would have enhanced more metabolic pathways, making their bodies more effective at using fat as a fuel source. Ultimately, their varied movements would have increased the range of their bodies’ capacities, enabling them to not just survive but thrive in different environments and under different conditions.

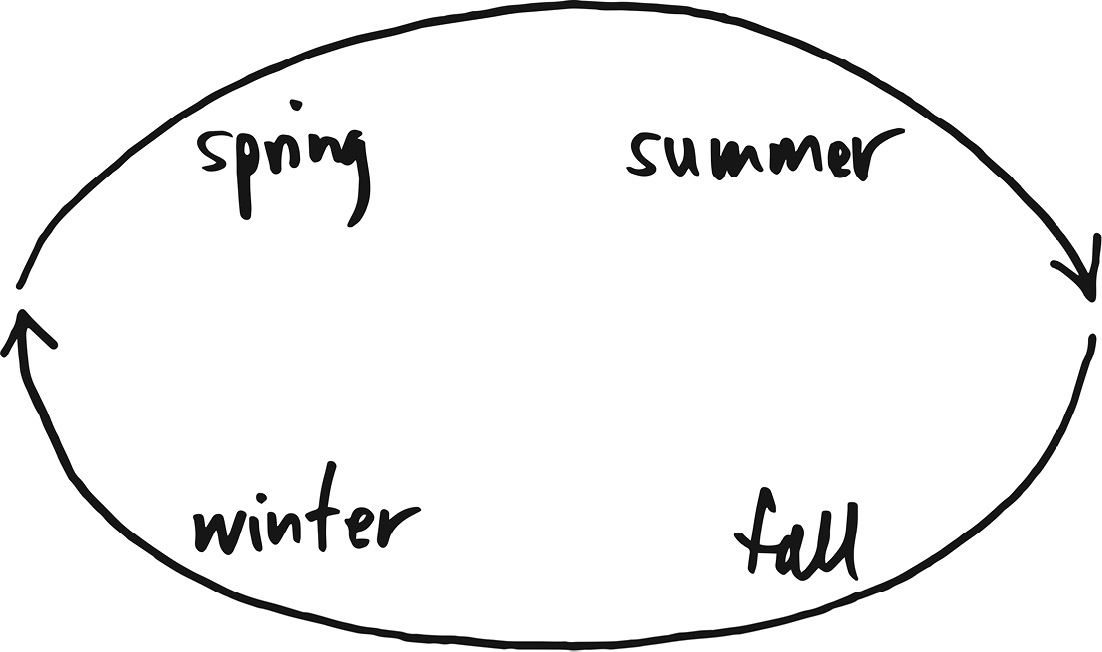

We moderns should return to such oscillatory movements to enhance different metabolic pathways and render our bodies stronger and more resilient. Such movement oscillation, however, looks different than it did with nutrition. When I described the seasonal oscillation model with nutrition in chapter 3, you may have visualized a circle with four quadrants, each representing the four seasons. When it comes to movement, visualize instead an elongated ellipse. Spring and summer run along one edge of the ellipse and fall and winter along the other. With this visual in mind, you can think of roughly varying your workouts not among the four seasons, but rather between two general poles of winter and summer. In performing these two major oscillations, you’re providing your body the opportunity to adapt to different stimuli, which serve to strengthen our bodies, just like it did our ancestors’.

With movement, as with nutrition, the summer/fall and winter/spring transitions matter most. The transition from winter to spring is relatively easy to accomplish because, as dopamine-driven, novelty-seeking human beings, we spontaneously seek expansion in the springtime, getting into the garden, doing spring-cleaning, and starting a new exercise program. In the summer months, generally speaking, we should incorporate large volumes and long durations of general movement, like hiking and being out and about at the park or the lake. Think of the classic summertime staples of bike rides and throwing the Frisbee for your dog or with your kids. As we enjoy mostly pleasant weather outside, we should choose to do a lot more walking and carrying, like rambling to the grocery store and ferrying our groceries back home. Here you might pause and think, “I’ll look crazy if I walk a mile to the store!” Yes, you might, by conventional standards. In modern society, most people don’t leave the car at home and deliberately move their bodies instead. But we must substitute convenience for movement, because our society’s default is movement minimization. And if the headlines are right, we’ll soon miss even the short walk to our cars as we head to the supermarket, since most of our groceries will arrive at home via drone delivery. Have you seen the animated film Wall-E? Yeah, it’ll be like that.

The winter-to-spring shift might be easy, but the difficult transition—and the place where we can easily become stuck—is the pivot from summer to fall. We’ve observed how the last ten thousand years of human history, premised on agriculture and civilization, orients us to the logic of summer—the allure of expansion, craving, dopamine, pleasure, ease. Whether it’s staying up late, feasting on carbohydrate-rich foods, or basking in artificial light, it’s easy to get stuck in summer. The same holds true for movement. As the leaves change color and the colder weather approaches, we’ll naturally begin spending less time outdoors, and thus doing less general movement. Our whole world, literally and figuratively, should contract during these months as we spend more time resting and nesting at home.

But just because we experience an overall reduction in the duration of our activities doesn’t mean we should become sedentary in these months. Instead, we should vary our movements, substituting longer, easier workouts with shorter, harder, interval-based or sprint-based training. We should also adjust the nature of physical connections. Summertime lends itself to outdoor activities with lots of people—we enjoy the excitement of exploring groups and the rush of meeting new acquaintances. Running a 10K with a bunch of friends makes good summertime sense. In the fall and winter, the nature of our movements changes, as our more indoor and concentrated efforts, performed among close family and friends, entail more intimacy and vulnerability. Think of working with a personal coach, or training with a gym buddy.

Our movement patterns should thus obey the oscillatory logic we’ve seen throughout this book. Fall’s and spring’s movement should be moderate in both intensity and duration, but only as transition points between the more polarized movement extremes of summer and winter. The pivot from summer to fall—and from winter to spring—represents a moderation of both intensity and duration, where winter itself sees more of a reduction in total activity by duration and time, and an introduction to short, hard, interval-based or sprint-based training that isn’t present at all in the summertime.

Let’s say you wanted to take up a competitive sport like running, and to oscillate your training seasonally. In the spring, you might begin by engaging in low-intensity, moderate-duration preparation. You’re just getting started. This would represent your aerobic period early in the training season and should be full of low-intensity runs, or something referred to in the lingo as “base building.” As you get more fit, you can lengthen your training sessions. As you approached the date of your event, be it a ten-kilometer run, half marathon, or ultra-marathon, summer’s long training would gradually yield to fall, and you would reduce your overall exercise duration. At this juncture, you would increase your overall intensity, training closer to your aerobic thresholds, or doing some sprint work and “sharpening” activities. But you would also want to scale back or eliminate your long, base-building runs in turn. This transition from summer to fall wouldn’t be stark, nor look significantly different. It would simply involve a tapering off general activity, and a ramping up of intensity. Picture a sine wave, not a right angle.

Unfortunately, whether we’re preparing for a race or simply going about our days, we don’t tend to maintain a foundation of basic daily movement, accompanied by slight seasonal oscillations. Most of us are slaves to our environments, which naturally lead us to move very little. While my writing here is a nudge (if not a vigorous shove) in the direction of a high degree of “healthy deviancy” from the status quo (to use the term coined by my dear friend Pilar Gerasimo), we can only opt out of our environment so much without becoming misfits or outcasts or risk losing the jobs we depend on. If you work away from home for ten or twelve hours every day, you probably won’t break out the vacuum cleaner each night just to elevate your heart rate. If you live on the seventh floor of an apartment building, I don’t expect you will volunteer to carry buckets of water up and down the stairs for an hour, as great as this may be as a workout. Without being too extreme, or arousing the concern of our neighbors, we must find ways to reintroduce a basic level of movement into our lives. Then, and only then, can we begin to oscillate those movements on a seasonal basis.

Become an Exercise Generalist

So, what should we do—get on that treadmill more often? Hop on a stationary bike or attend CrossFit classes three times a week? It’s not so simple—these and other popular forms of exercise are actually part of the problem. Ours is a world where you can shop online for a robotic vacuum cleaner so that you no longer need to vacuum your home (because who has time for that?), while at the same time you must buy exercise equipment or a gym membership to ride a stationary bike or walk on a treadmill to improve your cardiovascular health. Just like the standard American diet has stripped the nourishing components out of naturally occurring nutrient-dense foods and replaced them with ultra-processed, nutrient-poor food products, so we’ve stripped the nourishing movements from our everyday life. In the name of efficiency, productivity, and ease, we’ve stopped walking, carrying, pushing, and lifting—the very activities that make us strong, functional, and durable humans for decades. Then we reincorporate some form of (processed) movement back into our lives via our regular exercise programs.

As the brilliant biomechanist Katy Bowman has observed, humans have transitioned from movement generalists to movement specialists. We now perform an ever-narrowing range of movements that leave us overtaxed in some areas and undernourished in others.11 Think of factory workers performing the same repetitive tasks hundreds or thousands of times per day. (As a physical therapist, I often treated “overuse” and “repetitive strain” injuries.) Or office workers whose movement specialization entails being seated at a desk and pecking away at a keyboard, gaze fixed on their screen. Many of us, regardless of occupation, outsource our baseline needs, like acquiring food, shelter, and fuel, to the specialized movements of others, and then only engage in highly specialized movements as it relates to a singular sport or exercise, such as running, cycling, or tennis. When it comes to movement, we’re effectively eating potato chips and chocolate bars, and then consuming a multivitamin (i.e., a narrowly defined, non-oscillatory activity), and expecting to be healthy.

It’s true that in order to fulfill a large chunk of the three major elements of movement I outlined above, most modern humans must engage in some form of planned and structured physical activity, exercise, and training. And many people choose to do just that. But the classic mistake is to go from low levels of any activity to immediately specializing in one, like jogging, cycling, or obstacle-course racing, and performing said activity at virtually the same frequency, intensity, and time (duration) all year-round. Consider the jogger who shuffles around the park at the same speed every day, for years on end, not getting any fitter or faster, but nursing a progressively deteriorating lower back, hips, and knees. The frequency is the same. The intensity is the same. The duration is the same. There is no oscillation. Things get worse over time.

Those starting out with high-intensity interval training programs, such as CrossFit, often fare similarly. They begin well enough with high-intensity, relatively short-duration (e.g., ten minutes), low-frequency (e.g., one to two days per week) workouts, all of which contain some variation (read: oscillation). But then, slowly, people’s participation tends to increase to year-round high-intensity workouts, with increased duration (either longer classes or multiple classes per day), higher frequency (five to six days per week), and no real oscillation. These athletes become increasingly exhausted and their relative effort in each workout slumps. Soon enough, the six-days-a-week, twenty-minute CrossFitter is flatlining on the same “chronic cardio” as the six-days-a-week, twenty-minute park jogger. Doing different movements but using the same metabolic pathways isn’t true variation.

I often see destructive chronic cardio patterns among weekend warriors—people who engage in demanding physical activity during their off-time, which usually falls on the weekend. Many of them choose activities that afford little to no oscillation in their movements. They live a largely sedentary life during the week, not engaging in general activities like walking, lifting, carrying, or real-life functional strength movements. On weekends, during mountain biking workouts or recreation league soccer games, they push their bodies really hard. Such weekend warriors oscillate, but in a destructive way: they work too hard on their chosen specialties when they should be taking it easy, and take it too easy (perhaps because they are too tired and worn out from previous workouts) when they should be pushing a bit harder. They aggregate toward a middle ground, maintained across the year, that is both too stressful at moments and not stressful enough at other times to develop a healthy baseline of fitness and physical conditioning.

One need only glimpse nonindustrialized traditional cultures to see evidence of our generalist roots. In such cultures, people still use basic, labor-intensive tools, replicating the broad movement patterns that drove the evolution of our physical attributes and capacities. In contrast to modern, industrialized, automobile-centric societies, members of traditional cultures walk. A lot. In fact, they engage in a relatively high volume of light-to-moderate walking, in the range of three to ten miles per day. With the exception of those engaging in some form of intentional cardiovascular exercise, most people in modern society cover less than three miles per day at a comparable intensity. Yes, even those with a Fitbit who walk around the block during their lunch breaks (which I do encourage!).

Members of nonindustrialized and traditional cultures move their bodies at a relatively low-to-moderate level of intensity across a wide range of activities. Those whom modern societies deem “fit” or “active,” by contrast, often participate in specialized sports or exercise, instead of more general activity. Modern people accumulate this activity at much higher relative intensities and sustain that intensity for much longer periods of time. Imagine covering ten miles across a day through such acts as fetching water, sourcing and preparing food, firewood, and other supplies, undertaking general chores, and maybe engaging in social activities or dance. Compare this to a typically modern scenario of driving everywhere, remaining seated most of the day, and then going for a six-to-ten-mile run at 80 percent of your maximum heart rate a few times a week. The former group is likely aerobically fit and strong, yet we wouldn’t think of them as such because they are not, in our modern eyes, performing a distinct, specialized fitness session.

Also consider the surface areas on which these activities unfold. In traditional societies, people living in major towns and villages walk or run on dirt, sand, and rough ground. This aids in the development of foot and hip strength and stability, promoting balance and protecting the body from falls and strains. Most modern cities feature flat, uniform surfaces of asphalt and concrete. As the Guardian evocatively put it, “Concrete is modernity’s foundation stone: it surrounds us in bridges, motorways, tunnels, hospitals, stadiums and churches—from the Roman Pantheon, which is what God might pour if he had a concrete mixer, to Clifton Cathedral in Bristol, which looks like the ashtray where he would stub out his cigarettes.”12

These compact surfaces might accommodate the modern corporate uniform of heavy, tight-fitting clothing and restrictive, heeled shoes, but walking, jogging, and running on them for even moderate distances can promote repetitive strain-type injuries to bone and connective tissue. And you don’t even have to run. Teachers, nurses, engineers, and others who spend a lot of time merely standing on hard floors can experience a painful foot-based inflammation called plantar fasciitis, as well as osteoarthritis, Achilles tendonitis, and even varicose veins.13 Of course, we typically address these maladies with more cushioning, controlling footwear, and anti-inflammatory steroid injections—strategies that often cause more problems than they fix.

Perhaps of greater significance to our current well-being is not cardiovascular activity, as we in the modern world call it, but activities of daily living that strengthen our musculoskeletal system, such as lifting, carrying, climbing, and throwing. People undertake such activities from a very early age in traditional egalitarian societies, continuing throughout their lives. If you have ever watched National Geographic–type documentaries on such societies, you would have seen the classic images of a woman carrying baskets of food, bundles of firewood, or large bunches of bananas on her head, often with a child wrapped around her hip. You might have watched this from the comfort of your couch and thought, “Poor woman!” Such high musculoskeletal-load activities, however, allow for the development of physical strength not seen in most modern, urbanized humans. That “poor woman” might face many issues in her life, but those don’t include a frail and weak body. She’ll be strong and independent for the duration of her life. Compare that to the ten million Americans who have osteoporosis and the forty-four million more who suffer from poor bone density.14

In their paper “Achieving Hunter-Gatherer Fitness in the 21(st) Century,” James O’Keefe and his coauthors produced a table of typical hunter-gatherer activities and their modern-day equivalents.15 Our ancestors performed high-load activities like carrying baskets of gathered food or wood while we moderns carry bags of groceries or luggage. It might sound equivalent, but it’s not. Our modern penchant for labor-saving conveniences has worked against us in each of these cases. Carrying our belongings has now become dragging luggage on low-friction wheels. Carrying children has become pushing them in strollers. Small, low-maintenance yards have rendered our gardening activities less extensive and strenuous. Wood, if you even need it, might come to your door presplit, and if you pay enough, they might even stack it for you.

The removal of these “burdens,” no matter how welcome we might find it, leads our muscles and bones to weaken from disuse. We then break them down even further via inflammatory diets, stress, lack of sleep, and insufficient sunlight exposure. These effects have their own scientific names: dynapenia (loss of muscular power), sarcopenia (loss of muscle mass), and osteopenia (loss of bone density). All three form an often silent, interrelated triad of decreasing physical health and function. These pervasive penias (as I have heard one exercise physiologist call them) grow increasingly apparent earlier in our life spans than we’ve ever seen historically. In traditional societies, elderly people often perform hard physical labor well into their sixties, seventies, and eighties. What strikes us as unusual and awkward activities—like carrying water on our heads or squatting for extended lengths of time—keeps people strong and functional over their lifetimes.

The effects of reduced muscular load in modern life are similar to what astronauts experience after spending prolonged periods of time in a zero-gravity environment. When we rely on a chair to support our bodies instead of our bones, muscles, and connective tissues, we are effectively creating a low-gravity environment. Something similar holds true when we use carts, elevators, and cars to move objects. It might take years of exposure to such low-effort conditions here on earth to match the deterioration experienced over only a few weeks and months by astronauts in space. But such physical deterioration undoubtedly takes its toll. We tend to shrug it off as “getting old,” but it’s not—it’s the product of unhealthy aging, driven by years and years of mistreating our bodies.

Bear in mind that our muscles aren’t just the mechanisms that move us. They also function as a secretory organ, and they release chemical messengers into the body, like your pancreas or thyroid gland. These messengers, called myokines, help to control your metabolism, as well as bone and immune health. Myokines also help to protect us from excessive inflammation (driven by inflammatory cytokines), and are present in proportion to our movement and muscle mass.16 I’m always frustrated by the commonly distorted meme suggesting that “you can’t outrun a poor diet.” It became popular in the mid-2000s to underscore the importance of good nutrition and physical fitness, not one or the other.17 I find that the adage mainly reinforces the notion that you really only need to follow a particular type of diet such as low carb or keto, and that strenuous muscular contraction doesn’t matter very much. That’s a dangerous, misleading conclusion.

While physical activity guidelines have recommended some form of weight-bearing or muscle-building exercise for decades, such prescriptions remain vague, if not outright glib. The US Department of Health and Human Services began releasing guidelines to help inform Americans about the importance of physical movement and health beginning in 2008.18 Some of their key findings include, “Adults should move more and sit less throughout the day” and “some physical activity is better than none.”19 They also recommend several key staples of good fitness, including moderate-to-vigorous cardiovascular/aerobic exercise, stretching and flexibility exercises, and even the development and maintenance of total body strength across a life span (though the overall emphasis still seems to be on cardiovascular health).

According to Todd Miller, an associate professor in the Department of Exercise Science at George Washington University, everyone should engage in strength training, but only about one in five Americans follow government exercise guidelines.20 But even for the 20 percent of Americans who do, these guidelines remain a starting point at best. Taking them at face value, it’s hard to know how to build muscle and bone strength safely and effectively to achieve a good range of movement through the joints (and people actually need range of motion more than the muscular flexibility they chase through stretching). Even more important, how do we actually develop the cardiovascular system? For all the emphasis on “heart health” and cardiovascular disease prevention, we shouldn’t forget: the heart is a muscle too.

The average person will probably associate strength training with bodybuilding, big muscles, and testosterone-filled gymnasiums full of grunting men. This perception, married to the public health and media bias toward cardio-based exercise, and the common understanding that weight loss requires us to “burn calories,” accounts for the popular notion that cardio is “king.” People think that the best way to burn a lot of calories is to perform exercises that lead to an increased and sustained heart rate. Gyms, moreover, are expensive and difficult to get to. It’s much easier to slap on a pair of running shoes or hop on a stationary bike and get your heart rate up.

In truth, poor cardiovascular fitness isn’t what stops you from picking up your three-year-old grandchild or getting out of a chair in your eighties. An efficient heart isn’t what stops you from falling over and breaking a bone should you lose balance. You interact with the world either by exerting force against something (for instance, walking up a flight of stairs) or by resisting the forces being applied to your body and dissipating their effect (for instance, minimizing the impact of a fall). For all of us, and especially women, gaining more physical strength allows us to engage more fully and self-confidently with the world than virtually any other exercise modality, and this is especially true as we age.

In recent years, high-intensity interval training has been the exercise modality du jour. HIIT programs might feature single bouts of maximum-effort sprints, or the classic (though potentially overused) Tabata intervals of twenty-second efforts interspersed with ten-second rest intervals and repeated eight times.21 Rooted in the circuit training of yesteryear, HIIT represents a welcome departure from traditional physical activity guidelines that have focused on high-frequency exercise most days of the week, at a moderate to vigorous intensity, and at relatively longer durations. Over the last couple of decades, more research has focused on the benefits of lower-frequency and higher-intensity training. Working through slightly different physiological pathways than the classic continuous aerobic exercise, these high-intensity intervals have proven themselves to be as beneficial as high-frequency, lower-intensity, longer-duration exercise, if not more. They’ve been shown to enhance overall fitness and wellness levels, not to mention decrease blood pressure and help control blood sugar levels.22

Exerting yourself at near maximum effort is structurally hard on the body, though, especially tendons, joints, and ligaments. We condition such tissues by undertaking a great deal of low-intensity movement each day, as our ancestors did via the many different types of lifting and carrying they performed. Once we restore our baseline physical fitness levels, we’ll be ready for such activity too. That’s because we’re almost hardwired to move in the right ways. Children tend to be natural sprinters, engaging in relatively short bursts of effort interspersed with longer periods of lower-intensity movement. Older readers may still remember how children used to develop strong physical conditioning via rough-and-tumble natural play, spontaneous dancing or wrestling, school physical education programs based on gymnastics or calisthenics, or the trialing of several sports.

Funding cuts for school physical education programs, greater emphasis on academics and technological savvy over physical health and development, the sad state of health care, technology additions, and a host of other factors have all made children less inclined to stay active. When children do select some form of physical activity, they often opt for a relatively specialized and highly repetitive sport. These weak, unfit children, who may have had quite negative experiences with physical activity, grow into weak, unfit adults who fail to prioritize physical capacity. Carry this effect across a couple of generations, and being relatively weak and unfit becomes the new normal.

Overcoming Polarization

Our extremes of excessively consistent, monotonous movement or a lack of exertion altogether form what we might term a polarization in movement. What we truly need is more of a balance or middle ground. Research examining the training of elite athletes suggests that most of their training (upward of 80 percent) takes place at relatively low to moderate intensities, while specific workouts relevant to their sport, state, and stage of competitive season take place at relatively high intensities.23 That is, they spend little time occupying the two polar extremes. Far from a concept applicable exclusively to elite athletes, this is a useful way for us everyday athletes to organize our own physical activity.

Starting out, you might want to perform low-intensity movements by taking a brisk walk or going for a leisurely swim or bike ride. At least 80 to 90 percent of your exercise volume should focus in this zone. This kind of movement shouldn’t feel very stressful, and should include other aspects of health such as natural light, time outside, interpersonal connection, and avoidance of smartphones and other screens. At the opposite extreme of the intensity scale, you should perform a few short sprints at the highest relative intensity you can manage. In practice, we might be talking about three hours of walking per week plus two ten-minute sessions of sprint-like movement, where each sprint-like effort might last five to thirty seconds.

Sandwiched between these two polarized extremes, forming the critical foundation for most people’s structured exercise routines, should be some form of progressive strength training. Given that we can’t necessarily change our environments to allow for more strength-building loads on our bones and muscles, working deliberately to make our bodies stronger is one of the most essential things we can do for our health. Strength training programs can range from body-weight movements (such as calisthenics or yoga), to using tools like dumbbells and kettlebells, to specific barbell and powerlifting programs. Yes, walking and sprinting are good, but neither will benefit you as much if you lack underlying musculoskeletal strength. Build strength first, develop cardio second.

In line with my seasonal model, we should oscillate these activities over the year. The long daylight hours and hotter temperatures of summer lend themselves to longer, lower-intensity physical efforts. Shorter, colder winter days lend themselves to emphasize high-intensity efforts, with perhaps the occasional longer, lower-intensity effort if the weather allows. Year-round, continue building foundational, core strength by engaging in lifting, carrying, and smaller, easier shifts like taking the stairs. Also, don’t forget to share these activities with others. The rush of sharing a thrilling descent on a mountain bike with a friend will bond you together. I’m not suggesting that authentic human connection can only happen in physical environments and circumstances. But, in my experience, the bonds formed hiking up a mountain versus driving to the same point are much deeper, largely due to the shared collective experience and challenge of physical movement.

A good friend of mine shares fifty-fifty custody of her daughter with her former spouse. When her daughter took vacations with her father, they would travel predominantly by car. They’d drive to a spot, have a look around, get back in the car, and go on their way. Her daughter would say the right things following such “adventures”: “it’s nice” or “so beautiful.” But she lacked the ability to describe the experience with more detail, texture, or emotion. With my friend, however, the daughter would lace up her hiking books and visit places like the old-growth rainforests in the Pacific Northwest. She’d look around, glimpse the soaring canopies of the ancient trees, and dig her boots into the dirt, feeling herself momentarily part of the biodiversity in her midst. With her father, she viewed the vistas in a detached way. With her mother, she had an immersive, three-dimensional experience, using her bodily movement to connect to her environment and her parent.

In a sense, the daughter straddled the worlds of mechanization and tradition. She received traditionally nourishing and bonding physical experiences with her mother, and the nonphysical ease of modernity with her father. Of course, she resented physical experiences with her mother early on, grumbling when she returned from a hike, tired, with blisters on her feet. Like adults, children prefer ease and immediate gratification. But when this girl grows into adulthood and looks back on her family trips, I believe she’ll remember the experiences with her mother most fondly and profoundly.

A Maori physical educator from New Zealand, Dr. Ihirangi Heke, draws on a similar principle of physical connection when describing how he increased the physical fitness levels of the young indigenous Maori population in New Zealand.24 He found that telling these youths to work out in order to stave off heart disease and other afflictions fell on deaf ears. So Dr. Heke devised a different strategy, tapping into the deep spiritual connection the Maori have with their environment and the deities that, under Maori lore, form the caretakers of these environments. Dr. Heke led his students on a hike up a particular mountain that had spiritual significance. If they struggled to make it to the top due to a lack of fitness, Dr. Heke asked how they could possibly enjoy such a spiritual connection with a mountain they couldn’t even summit. How was this showing respect for the mountain? These simple questions explicitly linking physical activity to spiritual awareness did much more to motivate his students to become fitter than simply exhorting them to run or pump iron.

In Maori culture, there are gods for different types of dirt, sand, wind, water, and even snow. By asking his students to experience the texture of different grains of dirt or sand, to discern the different types of snow or water, and to mimic birds or insects balancing in different winds, Dr. Heke also used movement to connect with a special environment. All the while, he increased the fitness and strength of his students without explicitly telling them to “exercise.” I know I wouldn’t ride my mountain bike if the sole aim was to increase my VO2 max (the maximal oxygen amount someone can use during physical activity) or lower my risk for heart disease in thirty years’ time. I am motivated to ride because it connects me with the warmth of the sun, a pleasing trail, or a hill summit. The spectacular views, in turn, provide a sense of exhilaration that I can share with my fellow riders or others I might meet along the way. In exploring all these connections, via my bike, I also happen to improve my aerobic fitness and reduce my risk for chronic disease. Experiences weigh more than obligations.

With these ideas in mind, my elevator pitch for how and why we should develop our physical fitness and strength boils down to this: move your body in a way that strengthens it, connects you to others, and allows you to explore your world.25 But be smart in how you engage in such movement. Don’t get your butt up at 5:00 a.m. to go for a run if you only got five hours of sleep. (Stay in bed. Really.) I’m moving (see what I did there?) away from words like “exercise” and “training” because they conjure images of grinding away at the gym, sweating your way through a timed 10K run, or spinning your way through a fitness class. While these can be good options in the right context, such a focus on fitness and exercise overlooks the importance of low-intensity movement like walking, hiking, or riding a bike and natural movements like crawling, balancing, climbing, and carrying. The latter activities all help to strengthen our bodies in ways modern life—and gyms—often cannot. Fun, playful, and restorative movements like throwing a Frisbee, playing fetch with your dog, running around with your kids, climbing a tree or a steep hill, dancing, massage, and sexual intimacy are all examples of movement that help us to connect with those we feel closest to while improving our physical health.

Given the nature and constraints of our modern lives, physical strength, rather than aerobic fitness, should form the central pillar of any structured exercise program. Resistance training, carrying, and weight lifting are all common methods of building a strong and capable musculoskeletal system. Short infrequent bursts of high-intensity activity, when added to plenty of regular low-intensity movement, give most people all the aerobic conditioning they need. I recommend varying the balance of such activities according to the seasons on the calendar and the seasons of your life.

Physical Fitness for Quality of Life

Some readers might find the discussion in this chapter frustrating. “But Dallas,” they might say, “just tell me what the best exercise program is!” I really can’t do that. I’m also not going to give you an easy answer like, “Just do CrossFit/yoga/jogging.” Such blanket solutions, from me or others, miss the mark. As always, context matters.

We must look at physical fitness more holistically, starting with becoming more attuned to the many movement deficits we face as a society. How often do you take the escalator instead of the stairs? How often are your groceries or books delivered to your doorstep? How much time in a day do you spend in a non-seated position? When we start asking these sorts of questions, we begin to realize how much we’ve made our world mechanical, easy, and convenient, essentially discouraging any physical movement. You might have rolled your eyes when I suggested you walk to your grocery store and then return home with your groceries. If so, you’ll think my suggestion of taking the stairs over the escalator is also annoying. But that’s a small modification we can make to get us moving and attuned to the presence or absence of physical movement in our lived environments. It’s only when we make decisions like these that we can cultivate a healthy deviance against our society’s anti-movement status quo, improving our physical health and connecting with others and our environments.

When you travel, try to make your time away more physically interactive. Get out of the car or tour bus, and deliberately immerse yourself in the environment. Navigate the meandering streets of Europe; take off on a mountainous dirt trail and see where it leads; pitch a tent with your kids, letting them pound the stakes into the ground, and then experience the wondrousness of sleeping amidst nature. Choosing more interactive and physically demanding leisure activities such as these will create a richer, more enjoyable, and memorable experience. You and your children will also become more primed to exploring movement in other areas of your lives, setting the stage for bodily integrity and future independence.

I witnessed the importance of cultivating lifelong strength when, during my physical therapist days in the mid-2000s, I worked with elderly patients on fall prevention and recovery. As I both observed and confirmed in the medical literature, leg strength represents one of the strongest risk factors dictating fall risk. Elderly people with higher leg strength fall less frequently and recover faster than their weaker-limbed counterparts.26

When elderly people fall, at least half the time it’s because they trip over their pets, the edge of the carpet, the toe of the stair, or something of that nature.27 In order to recover fast enough to regain balance, your body must have the muscular force to move your leg rapidly. People with stronger lower extremities—like legs and hips—are more likely to engage in general activity, like a solid strength-training program, that leads to stronger muscles, better balance, and therefore better reaction times (not to mention a more efficient nervous system).

It’s tempting to measure people’s health and fitness levels based on their muscular definition, leanness, or what they look like in a bathing suit. But as I hope I’ve conveyed, I’m most interested in long-term quality and enjoyment of life. And I believe that strong, durable, and resilient bodies are best able to access this. Those of us who emulate the general movements of our ancestors as closely as possible are better poised to enjoy vibrancy, health, and vigor throughout their lives, and to stay independent into old age.

I could ramble on endlessly about physical fitness. But the social connection that can arise from movement is especially important and worth focusing on. Homebound elderly who are so physically frail they cannot leave the house do not die of lack of formal exercise. They die from loneliness. Our ability to move ourselves independently connects us with other people and places. CrossFit’s industry dominance and social popularity ultimately has little to do with its programming, but rather with the social bonds and connections formed when humans experience and endure something physically and mentally challenging together. As we’ll explore in the next chapter, our social rootedness is perhaps the most important component of human health and well-being, eclipsing even a healthy diet and a robust physical fitness regimen.