CHAPTER SIX Anchors

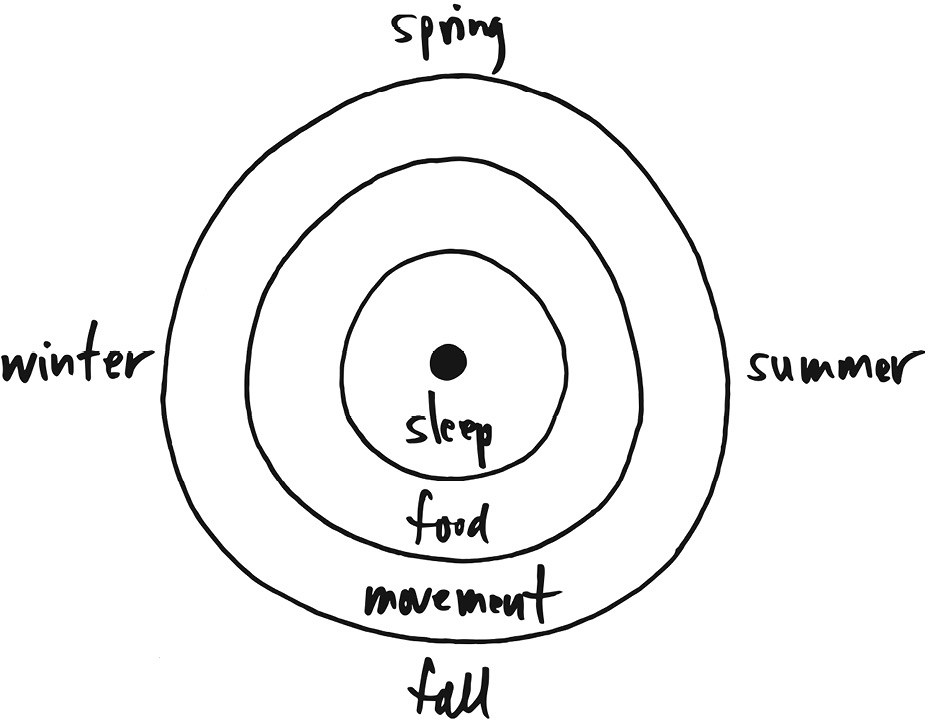

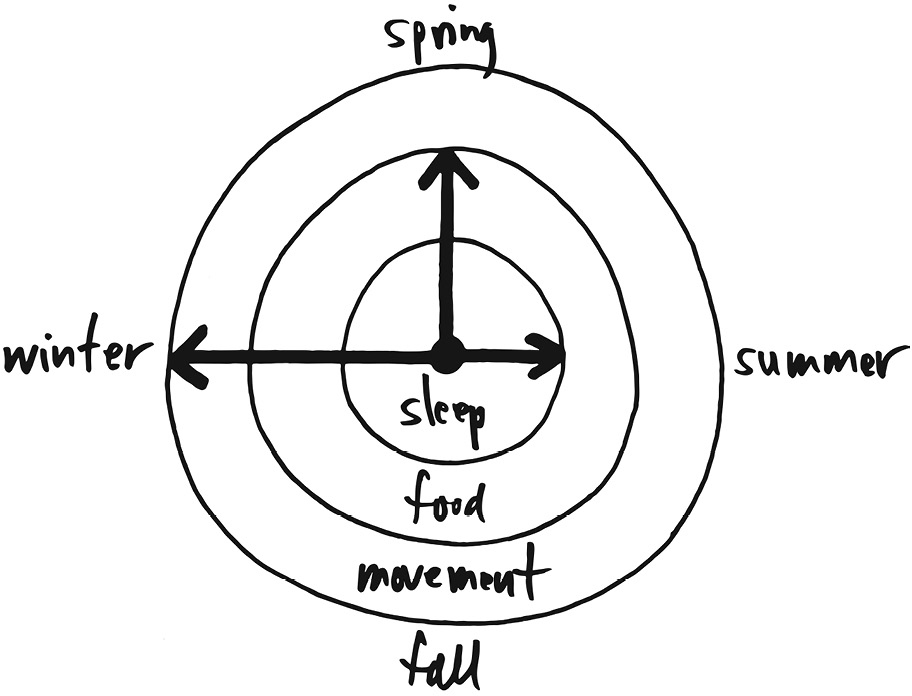

In 2012, before a small group at the Ancestral Health Symposium at Harvard, I unveiled my seasonal health model for the first time. On a 48 x 48-inch poster, I depicted all four seasons on a large clockface, with three concentric circles representing sleep, food, and movement (social connection hadn’t occurred to me as central yet). This complicated poster must have struck observers as a bit daunting.

As I explained to conference-goers, sleep, diet, and movement—three pillars of human life and my model’s core lifestyle variables—should properly oscillate throughout the year, with the height of summer defining one extreme and the depth of winter another. Sleep, I hypothesized, should be shorter over summer, with the early sunrise and late sunset, and more extensive during winter’s prolonged periods of darkness. Our diet, I argued, should oscillate from higher-carbohydrate and lower-fat content in the summer (with fruits, vegetables, and honey available) to lower-carbohydrate and higher-fat foods over winter (with fatty animal products more plentiful). The lighter, warmer days of summer provide occasions, I said, for longer and lower-intensity movements like hiking, brisk walking, and so on. Winter’s shorter days, by contrast, lend themselves to brief, higher-intensity bursts of activity.

I described how our society had resisted the less immediately gratifying seasonal oscillations of the cooler months, as we’d become locked into perpetual summer. To help convey my ideas, I made the presentation interactive, moving the poster’s various clock hands to demonstrate the common lifestyle/seasonal mismatches we’ve considered in this book, such as eating a winter diet (low carb) while doing summer exercise (chronic cardio) and getting consistent summer sleep (up early, down late), irrespective of the actual season.

What I didn’t realize at the time was that my seasonal model missed something crucial: an anchor point. For all my emphasis on rhythms, seasons, and cycles in this book, you could easily conclude that human beings exist—ideally—amid permanent change and flux. Today, I know differently. While all the seasonal and lifestyle oscillations I’ve described in past chapters are crucial, so, too, are the fixed points—the constants—that ground them. Oscillation itself depends on fixity. A pendulum, after all, swings on a fixed point that anchors and enables the instrument’s oscillation. A teeter-totter moves up and down on a fixed central axis. A wheel revolves around a central fixed axle. When navigating a voyage, we begin with a fixed geographical location or map, and then chart our movements relative to that position.

The same principle holds for seasonality. Amid life’s variability, we must maintain stable, year-round sources of dietary protein, very dark nights and light-filled days, functional movements like walking, lifting, and carrying, and a close group of intimate connections. These dietary, sleep, movement, and social requirements don’t change seasonally, and allowing for them makes my seasonal model less dizzying and daunting. Rather than trying to juggle multiple variables in a life that perhaps already feels chaotic and overwhelming, you can instead focus on anchoring yourself in a stable set of unchanging practices. Oscillation is important, but I now realize that these anchors—the constants—form the most critical linchpin of my seasonal model. You need to get these right before you focus on the oscillation.

Return to Ritual

I first realized the importance of anchoring specific lifestyle components after hearing my friend Baya Voce’s 2016 Salt Lake City TEDx Talk called “The Simple Cure for Loneliness.”1 Baya is an expert on human connection, serving as chief strategy officer of Secret Experiences, a design company that helps organizations create meaningful and lasting experiences. Human connection also suffuses her life and purpose. It’s why she joined a reality TV show in her early twenties, and why she and I met nearly weekly for a time to explore that topic.

To overcome the epidemic of loneliness that afflicts our digitized, disconnected world, Baya proposes ritual, not in the sense of a religious or spiritual exercise, but of an activity that anchors us socially. Ritual is so powerful because it’s repeated action plus intention, says Baya. When these two are combined, ritual becomes ingrained just like habits do.

Baya and her friends decided many years back to build ritual into their workweeks. Every Monday night, they pulled on their leggings and gathered at one person’s house, poured a glass of rosé, and piled on the couch to talk. Think of the couch as the metaphorical fireplace around which our ancestors once gathered. On many Mondays, the women arrived excited, ready to share news about their careers, families, and relationships. Other times, they were dispirited, and sometimes devastated, sharing painful details about miscarriages and divorces. Through grief and celebration, however, the ritual remained a touchstone, allowing everyone a fixed point from which to navigate their connections, both inside and outside the group.

It took a moment of extreme crisis for Baya and her friends to recognize their ritual’s full meaning and power. The year was 2016, and they were on vacation together in France. Having arrived in Paris for the first time, Baya was charmed by the city’s iconic shutters and windowsills as well as the sweet smells wafting from the bakeries. She admired France’s ritualized mealtimes, during which people ditched their electronic devices and spent several hours enjoying a meal and connective conversation with close friends and family. But the warm glow of novelty and happiness ended suddenly when Baya and her friends arrived in the city of Nice. It was Bastille Day, and, in a horrifying terrorist attack, a man had just driven his truck into a crowded street, killing eighty-four people. Amid the fear, anxiety, tragedy, and loss, it would have been easy for residents of the city to retreat to their homes, seeking safety and solace in private. But not twelve hours after the tragedy, storefronts and restaurants had opened their doors, welcoming people in to congregate and connect while partaking in France’s cherished mealtime ritual.

Inspired by what they saw, Baya and her close friends likewise returned to the anchor that had served them so well. That summer night, thousands of miles from home, they went back to their apartment, got into their comfy clothes, poured some rosé, and piled all together onto the couch. “So my invitation to you today is simple,” Baya said during her presentation, reflecting on this ritual. “Don’t do something new. Find something you’re already doing with your friends and families, your intimate relationships, or within your communities, and do that thing over and over and over again. Do it with intention. Do it during the good times and do it during the mundane. So when the inevitable emotional storms hit, you have your ritual to go back to. You have your very own anchor of connection.”

Listening to Baya’s talk, I asked myself the same question I explored in chapter 5: How did we as a species become stuck in an epidemic of loneliness? Why do we lack these grounding, core connections that rooted our ancestors, and that still root residents of the Blue Zone societies, who experience exceptional longevity and above-average happiness? My thoughts turned to the discipline of psychology and to attachment theory, which I’d found helpful as I’d wrestled with depression and a lack of meaningful relationships. Popular in the psychotherapy community for decades, attachment theory holds that secure connections—what I call “anchor connections”—are critical for human psychosocial health.

We seek these profound, anchoring connections early in life, typically from a parent. If we experienced parental security in our own childhoods, we move through life with greater physical and emotional security; if we didn’t, we sometimes develop insecure attachment styles, avoiding others or anxiously attaching to them.2 Either way, our desire for this firm social base—whether we received it as children or not—remains deep-seated and persists into adulthood. To attain psychosocial health and well-being as adults, we must embrace these desires and attach (or to use my vocabulary, anchor) ourselves to close family, romantic partners, parents, children, or friends. They alone can provide us a consistent, secure base from which to navigate an uncertain world.

Though we can’t be certain about how attachments functioned among our ancestors, we can infer that they enjoyed rooted connections, and that such bonding and solidarity provided neurological and psychological advantages. If ancestral babies didn’t receive adequate amounts of the hormone oxytocin from their caregivers, for example, deeply bonding them during early infancy, they would have been less likely to thrive.3 Something analogous held true for the tribe as a whole. A strong man with great hunting prowess, an especially observant female forager, someone with especially strong intuitions: primitive societies had a place for all of these different people, assigning them roles relating to food acquisition or, in the case of someone gifted with insights about human existence, perhaps the role of shaman or religious guide (that is, someone who stood at the intersection of the physical and spiritual worlds, and could access unseen forces). This diversity of characteristics, preserved in groups, allowed our ancestors to better mobilize in times of hardship and survive. Because tribespeople were closely rooted to one another, because they bore solid attachments to one another, the group stood a better chance of surviving with more varied skills and abilities.

The same principle should apply in a modern context, where resources, talents, physical strengths, and intelligence aren’t equally distributed among us all. As social animals, we don’t have the capacity to go it alone, nor should we want to. Our best hedge against life’s uncertainty and difficulty is a core group of intimate acquaintances. One of the hallmarks of anchor connections is that they are deep-rooted, predictable, and reliable—imperfect, perhaps, but stable. As my friend Katy Bowman, whose work on biomechanics I explored in chapter 5, has observed, many people around the world—especially where I live in Utah—stockpile food, water, weapons, and gold in case of apocalyptic catastrophe. But as Katy commented in personal conversation, she doesn’t do that. Instead, she described a different strategy: handpicking a small group of people to serve as a capable, resilient safety net for tough times.

Katy seemed to echo Baya’s thinking; both treat people as our most valuable resource. They are right. You might have millions of dollars in the bank, but what happens when you receive a cancer diagnosis? What happens when you’re emotionally stressed or lonely or riddled with anxiety? No money, power, or influence can ease those heartaches. Only the emotional support of those psychologically and emotionally proximate to us, the people to whom we give access to the deepest parts of ourselves, can help. To prepare ourselves for life’s uncertainties, we must develop sleep, eating, movement, and social anchors. Anchors give us something to hold onto when the storm rages around us.

Security and Stability

You might still be thinking: Dallas, here you are, deep into this book, arguing that the starting point for living wilder, more rhythmically attuned lives must be our fixed anchors. What gives?

Anchors have always informed my thinking, even when I didn’t realize it. On reflection, the Whole30 program is an anchoring framework for our food selection and meals. It asks participants to create a dietary anchor—a base diet lacking processed food products, legumes, grains, dairy, added sugars, and other known sources of bodily inflammation. Once that dietary reference point is established, people can build a broader, more individualized dietary framework, which hopefully includes some oscillation, like eating seasonally.

Most of us already have well-established anchors in our lives, otherwise known as our habitual behaviors. Chances are, your alarm goes off at the same time every workday, whether you are ready to wake up or not. You might have attached yourself to your favorite cereal as a way to start your day. You might connect with the same social media accounts, via the same device, as you eat your cereal. And your morning commute or workout might unfold along the same route every day that you do it.

All too often, however, we’re anchoring to the wrong things, and as a result, we oscillate incorrectly (or not at all). We anchor to late nights and alarm-clock mornings, shifting to the occasional early night and natural wake-up. We anchor to highly processed, predominantly refined carbohydrate foods throughout the year and shift to the occasional nutrient-dense, high-quality protein meal when our bodies start yelling at us about it. We anchor to our habitual cardio exercise and shift to the occasional strength-training session in the weight room or in the garage. We anchor to countless hours of image and content creation for our superficial social media connections and “community” and shift to occasional real-life interactions with friends, loved ones, and community members.

We’ve constructed and accepted these environments, and the short-term dopamine rewards they give us powerfully reinforce them. Sure, you’re tired and a good night’s sleep is exactly what you need. But the allure of your social media feed or the TV series you are binge-watching is far more powerful than your desire for a good sleep. If you started an Instagram account to promote nourishing, seasonal, and locally grown whole foods, but you get three times as many likes for posting photos and recipes for cupcakes and grain-free cookies, guess what you’re going to keep doing?

That’s not your fault, given the powerful forces anchoring us to the status quo. Legions of trained psychologists, sociologists, and behavioral analysts have carefully engineered social media platforms to play on our insecurities and hold our attention for as long as possible. The entire modern “attention economy” is based on extracting time from our lives, so that businesses can benefit economically from it. The visual design, colors, time delays, and notification pings play on our fears of missing out and our deep-seated desires to avoid rejection or exclusion from social norms. Social media has taken a natural human instinct—the comparison of ourselves to others—and flipped it. Instead of comparing ourselves to our fellow tribesmen, whose collective intimacy afforded us little privacy but also little loneliness, social media encourages us to maximize our strengths and minimize our weaknesses. We then scroll through feeds in which we compare ourselves, in all our flaws, quirks, and dreams, to others’ carefully curated and distortive self-representations. That’s an apples-to-oranges comparison.

Although we increasingly recognize the toxicity and hollowness of such interactions, it’s still scary to limit, let alone reject, this fast food of connection. It’s just like the painful transition from summer to fall that I’ve described throughout this book. Altering your current, maladaptive fixed anchor points and following a new, seasonal, cyclical path is tough. Before I outline my framework’s key anchor points, let’s acknowledge the constraints and limitations we face in making such changes. You might be a shiftworker (or a night owl). You might have a long daily commute. You might live alone, with few close, real-world connections. You might support a tribe of hungry teenagers on a limited budget. In these and other ways, your current life might prompt you to adopt unhealthy behaviors, but they are familiar, and grounded in routines. Breaking these habits for something novel, different, and healthier might seem daunting.

For most of my life, I struggled with what attachment theory would term an insecure attachment style. Because I didn’t form close attachments as a child, I was uncomfortable with intimacy and vulnerability in my adult relationships, and I would distance myself and shut down whenever family, friends, and romantic partners asked me about my emotions. But once I developed the seasonal model and understood the deep value of intimacy, I realized that I was electing to stay in a place of social isolation and loneliness, and that this was ultimately self-defeating and unhealthy. At that point, I had to make my model pragmatic and not simply theoretical. It’s one thing to write about the importance of close, intimate anchor connections and quite another to embark on a journey to actual intimacy. When I finally found the courage to become more vulnerable with others, I experienced profound self-transformation. One of the reasons I wrote this book was to offer readers an intellectual framework for improving their lives, and perhaps a catalyst to take that first step.

Since breaking unhealthy attachments usually means working against common societal and cultural norms, please approach this in a spirit of experimentation and creativity. Consider the primary anchor points I describe below for the four areas of health, and embrace the ones you feel you can integrate into your life straightaway. When those are well embedded, build from there. If you are in a position to make wholesale changes, trialing them, say, for one lunar cycle, fantastic. Your context, however, might allow you to make only one incremental change over the course of a season. That’s fine too. The goal isn’t to pull off a quick, total, but potentially short-lived perfection. It’s to make lasting and sustainable changes, season after season. And that might mean taking your time.

Anchor Points for Sleeping

Our sleep-wake cycles, the centerpiece of our circadian rhythm, should in theory sync with the changing light-dark cycles across the seasons. The changing lengths of day and night across the year should drive the oscillation of our sleep-wake times. This means that those of us living farther from the equator will experience greater fluctuations in our sleep patterns throughout the year. I can well imagine the reaction I would get from most readers if I were to say, “Anchor your sleep oscillations to the physical sunrise and sunset. Wake up at 5:00 a.m. (or earlier) in summer, and after 9:00 or 10:00 a.m. in midwinter.”

From a health perspective, there would be little wrong with this guidance. But, of course, our modern world doesn’t operate like this, and there are practical limits to how far we can opt out of our society’s asynchronous norms. A pragmatic approach to improving sleep is to create anchor points around our sleep environment (the inner sanctum of which is our bed and bedroom) and around some of the rituals and habits that impact our sleep quality and duration.

Think about your sleeping environment, starting in your bedroom and moving outward from there. There is a strong chance that many of you have your bedroom lit up like the Las Vegas Strip. You have phones, laptops and tablets, and perhaps worse, large television screens beaming into one of the smallest areas of your home, most likely with the main lights turned off. With low ambient light, your pupils open wide, taking in significant high-intensity blue-spectrum light from these screened devices. This leads to light-induced melatonin suppression, and subsequent disruptions to your sleep quality and quantity.

We therefore must anchor our bedrooms to darkness. To do so effectively, our bedrooms must become analog rather than digital. Yes, I’ve heard it before—you can’t make your bedroom analog, because you need your phone as an alarm clock. If you really need an alarm clock, buy a cheap analog travel device. If you absolutely cannot do that, create your alarm clock profile, put the phone in flight mode, and then place it under your bed or on the other side of the room. Do all of this before heading to bed so that you maintain your bedroom as a dark space.

Perhaps you need your phone in your room because you are on call, or the kids are out at night and you have told them to call you in case of emergency. Fair enough. Instruct such contacts to call rather than message you. Put your entire phone in dark/night mode, dim the screen to the maximum allowable limit, and disable notifications from every app. In short, transform your smart and bright minicomputer miracle machine into a dim, dumb phone. Or, get a cheap landline and circulate that number to loved ones who agree only to use it for emergencies.

If your phone doesn’t need to be in your room, remove it. The same goes for electronics larger than a phone. You have no need for a computer or television in your bedroom. If you enjoy watching TV to relax before going to bed, fine, but do this in another room. If your partner wants to watch television in bed and won’t remove it from the bedroom, then some tough love might be required—maybe one of you needs your own bedroom.

Recall that quality restorative sleep is predicated on darkness at night and bright natural light exposure early in the day. Irrespective of the time of day you awaken, or of the season, healthy sleep-wake cycles require you to get your eyes outside into bright light for as long, and as frequently, as possible. From the time you wake up, look for opportunities to increase your bright natural light exposure. Open your home’s window blinds as early as possible and delay wearing sunglasses. Increase your time outside as much as possible before you head indoors (between parking your car and entering your workplace building, for example). Take your breaks either as close as possible to a window with bright light streaming in or, better yet, go outside. I discussed this idea with a die-hard exercise enthusiast who now does as many of her morning workouts as possible outdoors, even trekking the equipment she needs out into the parking lot. As she’s reported, this has enhanced her sleep quality, her ability to recover from injury, and her performance strength and quality.

A light-meter app can come in handy. Most smartphones have a built-in light meter controlling everything from screen brightness to camera settings. Downloading an app gives you the ability to access this feature and to quantify the amount of light you receive, allowing you to either increase or decrease the light intensity to which you are exposed. I personally use an app called Lux Light Meter. Creating an awareness of how bright different environments are really helps to shift behaviors.

Even with the research I’ve done and the awareness I now have, I’m always surprised at just how different indoor and outdoor environments are. If it is 500 lux in your office, but 50,000 lux outside, then it is one hundred times brighter outdoors than indoors. Conversely, at night, if it is less than 5 lux outdoors, but 500 lux in your lounge room, then it is one hundred times brighter indoors than out. Your ultimate goal should be to decrease the magnitude of difference between each environment and anchor those exposures as best you can. In an ideal world, morning’s bright light would awaken you from your slumber and evening’s sundown initiate your sleep. But in this imperfect world, a little technology can help anchor us too.

My final recommendation for improving sleep-wake cycles and circadian rhythms is to anchor your sleep and waking times across the week. Most people understand the jet-lag effects of traveling across time zones, yet they often fail to recognize that varying your sleep-wake times (often by a few hours) from one day to the next elicits a similar jet-lag effect (commonly referred to as social jet lag). If you have ever experienced jet lag, you’ll know that even if you do manage to get sufficient sleep, you will often feel tired, lethargic, and out of sorts, highlighting the effect circadian rhythm disruption (independent of sleep time) has on our energy and well-being.

Try to establish anchoring routines around a set wake-up time (preferably a natural wake-up time rather than an alarm-induced one) and a set bedtime, along with habitual ways of winding down prior to climbing into bed. For those whose waking and sleep times change according to their work schedules, such routines hold even more importance, as these secondary zeitgebers can help your body to recalibrate to new sleep-wake routines. This in turn helps to improve, as much as possible, a less-than-ideal situation when it comes to our daily rhythms.

Anchor Points for Eating

In chapter 3, I outlined key anchors and oscillations for food and nutrition, the fundamentals of which I captured in my elevator pitch for how I eat. To jog your memory, here it is again:

Eat naturally occurring and minimally processed foods like meats, eggs, vegetables, and fruits. Choose these whole, nutrient-dense foods over packaged, processed foods, which are often nutrient poor but calorie dense. Food quality is important—a concept that includes where food comes from (local), how it was raised or grown (humanely; organic), and its overall environmental impact.

Aim for well-balanced nutrition—this means you must eat a diet of predominantly unprocessed plant-based foods, anchored by appropriate amounts of quality animal-based protein foods. This balanced combination of plants and animals provides you with all the nutrients you need, including all the proteins, carbohydrates, and fats naturally inherent in these food groups. How you eat—the social and cultural aspects of food and nutrition—is just as important as what you eat.

From this dietary approach, we can infer several anchors that endure across the seasons. I encourage anyone first embarking on a seasonal journey to start with the qualitative aspects of their meals and how they eat. Meals with quality whole foods represent the starting point in a good nutritional journey. I encourage three full meals per day, each of roughly the same size. Since most people begin with a small or absent first meal, and save an enormous meal for the end, this is a departure from common patterns. Each of these meals should take advantage of the protein leverage effect I detailed in chapter 3, anchored by a source of high-quality protein (preferably animal protein) roughly the size of your hand (an ideal approximation that scales to different body sizes).

You can select other foods to accompany this protein anchor based on seasonal availability. What is available seasonally should drive your food selections. Take a broad view, and regardless of the oscillating parts of your meals, anchor your diet to whole, single-ingredient (for the most part), minimally processed foods in each meal. This allows you to aim for a quality protein intake of approximately one gram per pound of lean body weight (your total body weight minus the weight of your total body fat), and will have transformative effects on you, your family, and your community. It sounds too simple, but it’s also massively impactful.

Anchor Points for Movement

In the West, where most of the population is sedentary, I’m not as picky about the particulars of regular physical movement. If your major seasonal mismatches include circadian rhythm disruption, poor sleep, and inadequate nutrition, I wouldn’t unduly focus on physical activity patterns. But if you can focus on improving your physical activity, begin by seizing every opportunity for incidental movement, embracing inconvenience, and rebelling against efficiency. Take the stairs. Walk more. Commute to work on your bike. Hand-grind your coffee rather than using a machine.

If changing habits in these areas is too difficult, then try working in purposeful bouts of exercise. The best exercise and activity programs encompass the three M’s: (Joint) Mobility; Muscle (Strength); and Mitochondria. Mitochondria are the microscopic power plants of our cells, and they need to function well if we are to be able to use food energy efficiently. We need a routine, preferably a daily one, that can guide our joints through their full range of movement, keeping them and their associated structures strong and mobile. We should also incorporate movements that allow for safe yet progressively high weight loads across the most fundamental of human movement patterns: squatting, hip hinging, lunging, pushing, pulling, and carrying. Finally, we should incorporate motions that nourish our mitochondria, the key energy-producing and regulating apparatus of our cells.

Traditionally, experts have considered cardio or endurance-type exercise (exercise with elevated and sustained heart rates) most beneficial to improving mitochondrial health. More recently, researchers and professionals have come to understand that short bouts of high-intensity efforts (such as interval training) elicit similar benefits. Strength training can also improve mitochondrial density and efficiency while enhancing joint mobility.4

If pressed to recommend one method of structured activity to anchor you throughout the year, I would suggest weight lifting, either as a stand-alone activity or as a complement to other functional strength movements like calisthenics. You could achieve strong outcomes, for example, by anchoring to regular yoga classes; adding CrossFit, Starting Strength, or some other form of basic strength training; and boosting your mitochondria with regular walking and general activity. Yoga, Pilates, or body-weight resistance exercises, performed at home, provide sufficient loading to build strength for nearly everyone, especially people just beginning their movement journeys. Bottom line: generating physical strength must be a consistent focus across time rather than a seasonally variable add-on.

Anchor Points for Social Connection

I’ve spoken of Baya Voce’s TEDx Talk and of the importance of anchor connections. Such anchors are our safe harbors. People constantly ebb and flow in our lives, but amid these seasonal and lifetime social oscillations, we must invest in and nurture the core connections that offer us the greatest sense of belonging and community.

We must also take steps to remain rooted in a sense of place. We often refer to our anchor places as home—our physical residence, rented or owned, that contains our belongings. A place of shelter, safety, and security. Think of the violation we experience when someone enters our home who is otherwise unwelcome. Home can also take on spiritual dimensions. I am Canadian by birth but have been an American resident for most of my adult life. Ask where home is for me—which land resonates most emotionally for me—and for all the beauty of Utah (where I currently live) and the many US states and countries I have visited, I’ll tell you my true homeland is British Columbia.

No matter where our life journey takes us, and no matter how many decades we’ve spent moving about during the “summer,” expansion phases of our lives, we all do best when we have a sense of place—either a physical or spiritual home—to which we can return. This might be a physical address, a homeland, or some other anchoring space, like a piece of furniture with your photographs and plants. In today’s freelancing and gig economy, many of us have inconsistent work environments, leaving us physically and psychologically unsettled. We might work at coffee shops and forgo our own vehicles for car-sharing apps like Uber. Even so, we can still find ways to enjoy anchoring spaces in our lives.

At my regular coffee shop, I have a favorite spot to sit and work. When I arrive and someone else is at my favorite table, I become almost visibly affronted. That’s because, in some small way, my physical and psychological connection to this coffee shop corner provides me a sense of belonging, just like my anchor social connections. You might have carved out a similar area in your home or workplace. Or maybe you regularly walk in a park near your home when you need to clear your head or have a favorite spot you and your family return to when camping. Maybe your town, state, or country provides an anchor for your overseas deployments in the military. These are all options. Make a mental note of these places/spaces, the feelings and connection you have with them, and why you always return to them.

Connections to people and places ultimately provide us a deeper understanding of and connection to ourselves and our personal sense of purpose. In reciprocal fashion, such self-connection helps us develop deeper connections with people and places. As I recently confirmed with a close friend, our core anchor connection must be to ourselves and our purpose in life. My friend sells health insurance and routinely finds herself emotionally involved with her clients (supporting them in either accessing adequate coverage or in making a claim). As she described to me, this tendency, combined with her husband’s health problems and her concern for the health of her adult daughters, all added stress to her life. When I encouraged her to prioritize her own well-being over her husband, daughters, and clients, she felt anxious about it, worrying that she would be letting these others in her life down.

After guiding her through a process to elicit her values, we found that caring served as her primary life value, defining her sense of purpose. She cared that her clients had the optimal insurance coverage to meet their health needs. She cared that their claims were met. She cared about her husband’s health and would do anything to prevent it from deteriorating. She cared about her daughters and wanted them to avoid the ill health she saw in many of her clients. Understanding this, I told her that if she let her own health and well-being deteriorate, she wouldn’t have the capacity to care for others in her life. That did it—something clicked.

Prior to our conversation, my friend’s sense of purpose and connection to self was solely contingent on the connections she had with others in her life. Such a tendency is widespread, especially in the modern West, where we tend to view people as either altruistic or selfish.5 In an attempt to demonstrate that we fall on the correct side of this binary and are generous, we sacrifice ourselves, purportedly for the good of others, and often at great expense to ourselves. I find it unhealthy to occupy an extreme at either end of the altruism/selfishness binary. To create healthy attachments, we must extend generosity to ourselves and to our deep anchor connections. Once my friend realized that all the caring she showed others should extend to her, she developed a richer internal world, and more capacity to experience self-love, self-respect, self-esteem, self-appreciation, and self-compassion. This in turn enabled her to be more present and emotionally available with other people. It’s admirable and noble to care for others and place them first. But we must extend such deep investment, generosity, and compassion to ourselves as well.

Setting Your Anchor

People. Places. Purpose. Dietary protein. Functional movement. Robust sleep routines. These are the important anchors that travel with us along life’s journey. They are an intentionally and unavoidably tangled web. Food connects us to people. It can connect us to places too. Food can fuel our physical, emotional, and mental energy so that we can achieve a sense of purpose. Dietary nourishment reduces our reactivity to stress, which makes us more receptive to, and more affiliative with, those around us. Insufficient sleep alters the default settings of our brain from pro-social to antisocial. When we’re exhausted and sleep deprived, we lose our connection with people and places; we lose our sense of purpose (or we lack the emotional bandwidth to explore our purpose in the first place, leaving us bewildered and generally uninspired). Physical capacity allows us to move freely and confidently, taking us toward people and places. It allows us to walk up the mountain or to swim in the sea or lake or visit a friend in another country. And perhaps most notably, fostering our most important relationships anchors us so that we can more gracefully and successfully weather life’s storms. People provide stability, and often serve as the greatest catalysts for feeling a deep sense of rootedness in and contribution to a larger whole. These anchors are beautifully and profoundly interconnected.

It still might seem paradoxical that anchors serve as the basis for our rhythmicity. But that’s precisely how the natural world works. The universe is perpetually ebbing and flowing. Its tempests and storms are dynamic and oscillatory. Yet such dynamism exists within a very predictable framework. There are 365¼ days a year—that never changes. Every lunar month contains the same number of days. Gravity is very predictable. If this all sounds overwhelming and too abstract, don’t worry. There are a few bedrock, foundational things you can do to tiptoe your way into a healthier lifestyle.

Maybe you are already experimenting with eating seasonally, or maybe not. Either way, you likely aren’t approaching rhythmicity in a coordinated, synchronized, or comprehensive way. And that’s okay. The anchoring principles we’ve examined will provide you with a baseline—the biggest return on investment for your personal health and happiness. When life gets crazy and you become stressed or lose your job or get an illness or suffer an unexpected death or end of a family relationship, you’ll have these anchors. Setting anchors is the first step in establishing a healthy life foundation. But before we can begin living in a seasonally oscillating manner, firmly anchored in our four lifestyle variables, we must first compensate for our extensive period of chronic summer living. As I describe in the next chapter, we’re all due for a prolonged period of healing—we all need a fall pivot and a therapeutic winter.