CHAPTER SEVEN Pivot to Heal: Fall and Therapeutic Winter

After completing my master’s degree at the age of twenty-two, I married my college sweetheart, started my career as a physical therapist, and began living a fairly conventional American life. At that time, I was poorly equipped to handle the pressure of student loan debt and the psychological stress of “adulting” and found that I felt better when I exercised. Hard. Often. I crammed a lot of competitive volleyball, running, climbing, strength training, and Olympic weight lifting into my twenties. Friends and strangers admired my physique and athleticism (which only encouraged me to do more training), but underneath it all, I had occasional inklings that all wasn’t well in the henhouse. Whenever I was unable to work out, such as when I was nursing an illness or injury, or when I was simply away at a conference, I’d become anxious, jittery, and irritable. I also had a nagging shoulder injury that stubbornly refused to heal, but that I also stubbornly refused to rest. Addictions are powerful things.

As I “matured” into my later twenties, I slowly realized that I had developed a psychological dependence on exercise, using hard training to deal with a life that didn’t feel deeply satisfying. I was using intense exercise to self-medicate and deal with financial stress, the lack of emotional connection and nourishment in my marriage, a lack of deeply gratifying social connections, and the extended illness and eventual death of my father from pancreatic cancer (which left me grieving and abruptly confronted by my own mortality). I also used exercise to quell my own anxiety and insecurity about my self-identity and my life’s larger direction and purpose. Not surprisingly, the people I often hung around with behaved similarly, so there wasn’t anyone with healthier habits to highlight my dysfunctional choices.

What I know now is that my story isn’t unusual. Many of us seek a reprieve from modern environmental stressors and our chronic summer lifestyles in workaholism, alcohol, food, sex, recreational drug use, compulsive shopping, and, yes, even exercise. In the case of intense or prolonged exercise, the structural and metabolic stress triggers hormonal responses (adrenaline and cortisol) as well as the release of feel-good endorphins. For our hunter-gatherer ancestors, these endorphins helped increase our physical pain tolerance, enabling us to fight or flee from dangerous predators and threats. But in the modern world, we’ve unconsciously repurposed these natural painkillers to manage other types of pain and stressors, like loneliness, social rejection, financial pressure, feelings of inadequacy, and lack of deep connection with our family, friends, and romantic partners. This works because the brain circuits involved with perception of physical pain also light up when we experience social rejection. That is, being excluded or breaking up hurts, so self-made painkillers are a convenient and effective way to deal with that. The problem, of course, is that the net effect of excessive exercise (when it’s long and/or very intense) is to add even more stress to an already overloaded system.

As I got closer to thirty, I began drawing on my academic background in anatomy, physiology, and physical therapy to really look at the impact that the chronic stress and excessive training were having on my body. After some reflection, I found that my behaviors weren’t very consistent with my priorities of physical and psychological resilience, and an overall high quality of life. I continued introspecting and slowly shifting my behaviors and values elsewhere in my life too. Around 2009, as I began to develop this seasonal model, I also began an incremental but significant overhaul of my life. I pivoted away from chronic summer. It wasn’t structured in exactly the same way that I organize it here, but the shift was comparable.

Addressing my exercise addiction, I started training less often, moderating my training intensity when I did exercise, and taking more recovery time in between training sessions. I focused more on strength- and power-building movements, and didn’t thrash myself so hard or so often with intense conditioning work. This allowed my chronically under-recovered body more time to recover and heal. At the same time, I adopted a Paleo-type diet, and started noticing new subtle and intuitive seasonal urgings around food, like more sugar cravings in the summertime (which match the seasonal availability of fresh fruit), and a yearning for hearty stews, meaty soups, roasts, and root vegetables come wintertime. My larger social disconnections also became apparent, like the lack of meaningful intimacy and vulnerability in my first marriage. I started paying more attention to personal growth and the value of deeper relationships, gradually extricating myself from summer-type, shallower intimacy by becoming more vulnerable with closer anchor connections (as described in chapter 6).

In other words, I was getting out of chronic summer and pivoting to fall.

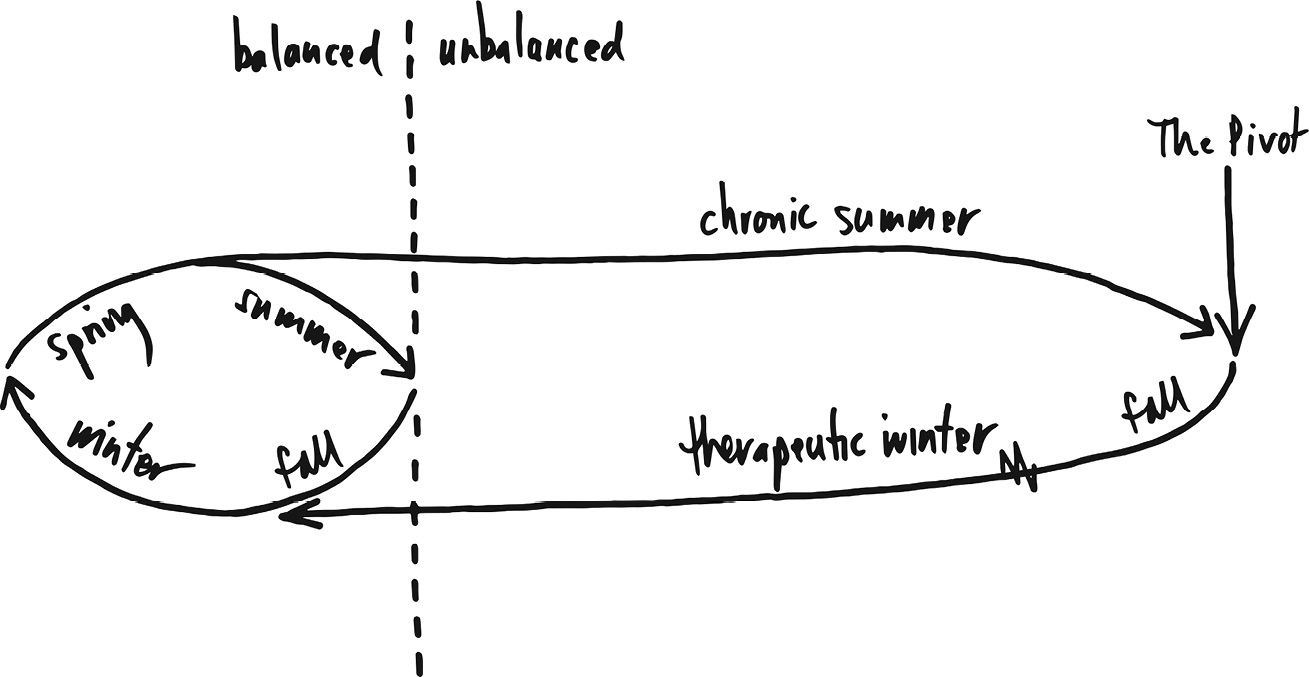

No matter your starting point when you pick up this book—whether you’re in the throes of stress addiction or you still feel pretty good for the moment, yet sense something isn’t quite right or believe you can feel even better—chronic summer living has likely left you feeling overstimulated, fatigued, beat down, and a bit unmoored. Our chronic summer civilization has left us, in one way or another, with circadian rhythm dysregulation, dietary imbalances, dysfunctional movement patterns, and a lack of meaningful social connection and self-awareness. This means that we all need an extended period of rest and restoration before we can fully embrace truly seasonal living. Before we can live in a harmonious and coordinated fashion with the seasons of the year, we must normalize, heal, and rebalance our topsy-turvy lives. To offset the damage we’ve incurred from chronic summer, we must embark on a period of extensive, comprehensive healing—something I refer to as the pivot to fall, followed by a therapeutic winter. I call it a pivot because it’s a directional change from our chronic summer’s focus on expansion, on consumption, on accumulation.

Chronic summer-style living has depleted us so extensively that, to use a financial analogy, we’ve all overdrafted our bank accounts. We’ve overspent our emotional energy, our waking hours, our physical health, our mental bandwidth. To get ourselves out of the red, we need a period of restoration, where we build up our psychological and physiological “savings.” The pivot to fall and its deepening into winter is a strategic recuperative strategy—a necessary first step before we can operate on a healthy, sustainable “budget,” where our lifestyle incomes and expenditures are roughly balanced. And this means that we can’t make partial, compartmentalized changes. If you’ve racked up some credit card debt, you’ll be able to dig yourself out of debt faster if you stop overspending on entertainment or vacations or clothing. But it’s only when you address your financial health in holistic terms—examining your expenses on housing, food, transportation, and all the rest—that you can achieve financial health and long-term solvency. Similarly, you can’t solve your chronic summer woes just by changing your diet or exercise program while you continue your erratic sleep patterns and self-medicate with likes on social media.

Turning Away from Chronic Summer

By now, we’re familiar with my model’s understanding of fall—a challenging, directional shift away from summer; a moment of deceleration, energetic contraction, simplification, self-examination, and interpersonal reconnection. We’re also familiar with my model’s version of winter as a prolongation and intensification of this restorative fall mode—a season of introspection, quietude, deeply nourishing and satiating food, and drawing even closer to our important anchor connections. Up until this point, however, we’ve been thinking of fall and winter as both seasons in time and as ways to shift behavior as we come out of the high sun of summer and embrace the shorter, cooler days of fall and winter. I’ve discussed oscillating the four keys of health over the four seasons, embracing summer sleep, eating, movement, and connection in summer, fall habits in fall, and so on across the four seasons of the year. But now, I’d like to expand the reach of these concepts, developing them as metaphors, symbols, and even overarching themes where we deliberately turn away from chronic summer in major areas of our lives.

The fall pivot and therapeutic winter each last a minimum of three months (a literal season), and ideally coincide with the actual fall and winter seasons. In optimal circumstances, you’ll discover this book in the spring, begin consistently implementing your anchor behaviors in the summer, embark on a pivot to fall in the actual fall, and give yourself three months (or so) of this directional motion before transitioning into the more comprehensive, far-reaching, and deeply restorative habits of a therapeutic winter.

But if you read this book in March or April, I recommend you extend your transition and focus on gradually slowing down. Give yourself a longer period to become mindful of chronic summer as you gradually decelerate and establish the various lifestyle anchors in your life. You don’t need to dive headfirst into the fall contraction right away, though you certainly could. If you instead happen to pick this book up in August or September, right as the seasons transition from summer to fall, and feel motivated to begin the pivot right away, do so, but understand that you might experience some attitudinal and behavioral mismatches and it might take a bit longer to fully feel fall’s deceleration. Embrace the transition with a spirit of openness and flexibility, and remember that there is no rush. There’s no time limit or ideal time frame for this transition; you have many years to let this cyclical approach seep into all the corners of your life. It’s okay if you don’t make all of the sweeping changes right away. This is your journey.

Though not impossible, it’s harder to begin the pivot in the warmer seasons because it’s a bit unnatural to embrace winter’s spirit of contraction in the dog days of summer. Summer’s longer days make it tough to relax into a winter restorative mode. And let’s face it: it’s hard to skip the summertime barbecues, fireworks, long hikes, and social gatherings in favor of staying home, sleeping more, and doing more reconnecting with yourself and those closest to you. Instead of fighting the natural, expansive seasonal urges to go do and see and feel and learn, gradually nudge yourself, and possibly your family, in the general direction of establishing solid anchor behaviors and eating more nutrient-dense whole foods, instead of trying to apply mismatched fall and winter principles in your spring and summer. Once again, it’s okay to slow it down. Once you’ve dialed in your rebalanced lifestyle habits in the literal fall and winter seasons, they are much easier to extend into the warmer months. It’s much easier to prolong your contracted social world and general restorative attitude into the spring and summer, and to continue connecting deeply with place and self and others during these months, than it is to start these big contractions during this time.

Here’s a guiding principle: coordinate all four keys of symbolic fall and winter with the literal seasons as quickly as is practical for you. And give yourself six months minimum (two seasons’ worth) of transition and extended healing once you have. This half-year period of healing is a minimum duration, and given that most of us are extricating ourselves from multiyear or multidecade habits—all of the cultural norms, expectations, conveniences, and habituated pleasures of chronic summer—it might be much longer before we’re physically and mentally ready to return to spring-type behaviors. And as we’ve already seen thus far, the pivot to fall is the hardest shift, as it entails a big directional change away from an exciting adrenaline- and dopamine-fueled summer. Once you’ve made that directional shift and move from fall to winter, the process will start to feel natural, intuitive, healing, and energizing because you are restoring what chronic summer has depleted.

In past chapters, we’ve considered each of my models’ four-fold variables—sleep, nutrition, movement, and connection—in relative isolation from one another. But we can only make a lifestyle pivot to fall and therapeutic winter if we address these variables simultaneously, just as I did over the last decade. As you read this chapter, resist the urge to dismiss any isolated recommendations I offer because you’ve already tried them or you heard that they weren’t really that important. You might have tried blocking out blue light at night, for example, or experimented with a Paleo diet, or tried reconnecting with your spouse in a more meaningful way. You might be interested in ancestral health and may have even incorporated some of the elements of this book into your life. You might have taken on a Whole30 program, or even lived a Paleo lifestyle for an extended period of time, perhaps seeing remarkable shifts in body composition, insulin sensitivity, energy levels, mood, and the reduction of various inflammatory conditions. But while you likely have experimented with different lifestyle variables in isolation, you haven’t undertaken the comprehensive fall pivot and therapeutic winter in its totality, approaching sleep, diet, movement, and connection in a concentrated and integrated fashion. You haven’t approached seasonal healing in a synchronized way. Well, now’s the time.

As I argue in this chapter, one of the causes of our frayed nerves, exhausted bodies, and lonely hearts is that we haven’t coordinated these different factors. We’ve overleveraged summer so badly that we all need a period of holistic, comprehensive renewal to get ourselves back on track. Doesn’t a pivot to a cooler, slower autumn, and then an extended winter of healing just sound soothing, if perhaps unfamiliar? Yeah, I thought so. Our civilization’s destructive chronic summer has bred such imbalance and disease; the solution is a fall pivot and therapeutic winter. Take your foot off the gas, let the engine come down from redline, cool, and simply idle for a while.

Falling into (Better) Sleep

Many people tend to overthink sleep by analyzing, planning, and structuring it, instead of focusing on removing the roadblocks that prevent it from naturally unfolding. A move to fall sleep patterns does precisely that, creating space for our body to achieve the rest, restoration, and recuperation we so deeply need every night.

To prepare your body for sleep each evening, provide environmental cues that allow it to feel relaxed and safe. For several hours prior to sleep, avoid intellectually or emotionally stimulating or stressful movies, books, and other media. If you read an evocative novel or watch a psychological thriller on Netflix, you’ll generate emotional arousal and perhaps a stress response that can make it much harder to settle into sleep. In these presleep hours, avoid frustrating or potentially triggering activities, like checking work email or assembling IKEA furniture. Those things will still be waiting for you in the morning. Avoid intense exercise within a couple of hours of bedtime as well. If your schedule dictates that you must exercise in the evening, decrease the intensity dramatically so that you don’t generate a stress response that blunts the secretion of melatonin that is required for deep, restorative sleep. If you must do your exercise in the evening, restorative yoga is better than an intense spin class. If you have a partner with whom you co-sleep, avoid emotionally intense conversations right before bed, as they’re very likely to trigger stress and impair sleep. An argument before bed will likely derail ideal sleep.

Avoid caffeine, nicotine, and alcohol at night. Many people use alcohol to decompress, especially if they’ve had a difficult or stressful day. But there’s a stimulating effect of alcohol, too, which is why if you have several drinks prior to bedtime, you’ll often wake up or toss and turn midway through the night.1 For optimal sleep, stop drinking three or four hours before bedtime so you have time to clear it from your system before syncing into that restorative sleep mode. Similarly, caffeine has more of a stimulating, sleep-disrupting impact than you might think. If you have trouble sleeping and you regularly consume caffeine, you have to at least consider its possible contribution to your sleep woes. If you have trouble confining your caffeine consumption to the morning, perform the following experiment: go a week when you drink no caffeinated afternoon beverages and see how your sleep fares. You might think caffeine doesn’t have any effect on your sleep because you can drink a cup of coffee and go straight to bed. But that simply indicates that you’re exhausted enough to achieve sleep despite chemical stimulation. You might be surprised by what a difference this simple modification can make in your sleep.

To create an environment conducive for restorative sleep, try to eliminate all light and noise pollution from your bedroom. As we discussed in chapter 2, this means avoiding screens, or at the very least acquiring blue light–blocking glasses if you absolutely must be on your computer or phone two or three hours before bed. There are several computer programs and apps, like f.lux and Night Shift, that help filter out those problematic blue wavelengths. If there’s any light streaming through your windows, hang blackout curtains or blinds to completely block it, so that your room is dark like a cave. If you are traveling or total darkness at home is not possible for some reason, wear an eye mask to bed. To avoid the abrupt and stressful experience of waking to an auditory alarm (the word alarm itself indicates a problem!), I instead recommend a light alarm: a dimmable light bulb that you can program to slowly brighten up your room in the morning, helping you to wake up by mimicking a natural sunrise. Start your day with light! Also consider Himalayan salt lamps that give off a soft, warm glow in the bedroom. Because they match the setting sun’s warm color hues, they are especially useful in the evening hours, and I find mine very calming. To reduce the impact of noise pollution, use an analog white noise machine in your room, or download a white noise app (always remembering to put your phone into airplane mode if it’s in your room at night).

Make your sleep environment simpler and more relaxing. Clean up your bedroom to make it less visually cluttered; whether it’s your preferred style or not, consider a minimalist decor for your sleep space. Think of your bed itself as a place for sleep, sex, and intimate conversation, but not eating, reading, playing on your phone, or watching TV. While avoiding stressful conversation with your partner is key, physical intimacy (with a partner or with yourself) is a great way to create the hormonal climate that helps you relax into a restorative sleep state. Adjust the thermostat for ideal sleep temperatures—around 65°F, or 18°C—and consider a few deep-breathing exercises or minutes of meditation in this cool, dimly lit, relaxing space. Aren’t you getting drowsy just reading about this?

A great, final way to achieve better sleep is to create a nighttime ritual. Read a book, snuggle with your kids or companion animal, take a warm bath with Epsom salts and relaxing essential oils like lavender, or have a cup of herbal tea. Keep a notepad next to your bed and if during these relaxing moments you come up with a creative idea or item for your to-do list, write it down. You’ll off-load the responsibility to remember it, which allows your brain to relax more completely.

As you read my recommendations for sleep, check in with yourself. Are there any ideas I mentioned that you immediately resist? Go back and reread the above paragraphs, jotting down one or two recommendations to which you feel most resistant—you’re either arguing about its validity or dismissing it as particularly useless. These are the places where I want you to start your pivot to a fall sleep pattern. Lean into the places you resist the most, like putting away your fast-paced novel or giving up your 3:00 p.m. cappuccino. What we most strongly emotionally resist is often what will benefit us the most. This principle applies to our other key behaviors too. Notice the things you resist, and instead of reflexively casting them aside, I challenge you to embrace them. I used to absolutely detest yoga, and I’ve more recently found it to be transformative, but that discovery could only happen once I leaned into the uncomfortable, awkward space. I suspect you’ll discover something really helpful once you use the indicator of internal resistance as your guide toward your most impactful shifts.

Becoming a Fall Foodie

Transitioning to fall nutrition might be the most straightforward lifestyle change you’ll make during this comprehensive pivot. Because whether you’ve been immersed in a healthy nutritional paradigm for years or are just beginning to think critically about your diet, the general movement is the same. Fall food selection represents a deliberate resistance to the overwhelming pull of summer’s cravings. It’s a more moderate nutritional position. Fall’s diet is sane and balanced—something that prepares your body to embark on seasonal oscillation for a lifetime.

In its broadest outlines, a movement toward fall eating involves consuming local and seasonal foods and anchoring them around a naturally raised or naturally fed meat, seafood, or egg protein source. Supplement these offerings with liberal amounts of nutrient-healthy fat sources like avocados, nuts, seeds, and grass-fed butter. In a broad sense, the really moderate diet I described in It Starts with Food is very much a fall-type diet. You can consult that book, any of the Whole30 resources, or simply return to chapter 3 of this book to orient yourself to fall eating staples and approximate portion sizes.

When prioritizing healthy, nutrient-dense fall staples, you’ll naturally eat fewer nutrient-poor and inflammatory foods. Remember that this lifestyle pivot will ultimately serve as a foundation for lifelong nutrition, so focus on what you are prioritizing, not what you’re excluding. The Whole30 program’s elimination of all added sugars, artificial sweeteners, grains, legumes, dairy products, and alcohol is wonderful and certainly a powerful and healthy way to eat. But it’s also a short-term experiment, not an optimal long-term diet. Think of the fall pivot as a gentler, more extended transition period of developing an integrated wellness lifestyle that’s flexible and achievable in your life. If you’ve completed a Whole30 program and you’ve found its principles energizing, that’s wonderful. Take the lessons you learned about your own food sensitivities, satiety signals, and energy levels, and carry them forward as principles, but not rigid rules. Don’t be afraid of veering “off-plan,” enjoying a sweet dessert treat or an alcoholic beverage on occasion. There’s room for occasional deviations because your fall pivot represents a broad directional shift in your journey, not a tightrope to walk.

To nudge yourself out of habitually consuming high-carbohydrate, high-sugar summer offerings, you might consider a check-in that I do with my son. When he was around age four or five, we started having conversations at the dinner table about how he felt after eating his meal. If he asks for a sweet treat, I cue him to pause, take a few deep breaths, and ask his body whether it’s really hungry for dessert. “Look,” I’ll usually say to him, “the priority here is the nutrient-dense meat and vegetables. If you’ve eaten all those meat and vegetables and you feel pretty good about things and you want a little bit of a treat, you can have that. But do you really want that right now?”

To my amazement and delight, he’ll often decline dessert. And like most of us, that boy loves dessert. “I thought I wanted dessert after dinner,” he’ll say, “but I realized I’m already full and I don’t really want to eat anything else.” Alternatively, he’ll say, “I feel good and I don’t need dessert,” or “I don’t need extra sugar.” At six years old, he’s developed an awareness about his own nourishment and satiety, and he continues to hone his self-awareness of his cravings. If we perform this brief check-in, we can all develop such an awareness, whether we’re six or sixty-six. When we’re deeply nourished and sated with complete proteins, healthy fats, and dietary fiber, we gravitate less to refined carbohydrates and sugar. This isn’t a panacea for your sugar cravings (since those are also exacerbated by chronic stress), but it might bump you out of a mindless, lifelong habit of eating dessert after most meals.

Perform this check-in with yourself, not just after dinner but following each meal. Are you craving ice cream, doughnuts, cookies? Ask yourself the following: “If I had a plate of panfried salmon and steamed cauliflower right now, would I want to eat it?” If that sounds appetizing, you are still hungry and should eat more nourishing food. But if you don’t want that nutritious meal and instead just want the ice cream, then you’re experiencing a sugar craving. That distinction is important when making the transition to fall. People often eat to satiety, especially in the evening, and then out of habit and driven by stress hormones—and the omnipresence of high-calorie, nutrient-poor summer offerings in our environments—reach for a sugary dessert. Sometimes such habits are long-standing, dating back to childhood when parents rewarded us with sugar-laden treats. Once habituated to summer’s easy sugar, we self-medicate or self-soothe with sugary (or at least carbohydrate-dense) foods, like candy, French fries, pasta, bread, ice cream, and pastries. Remember, refined carbohydrate gets rapidly converted to blood sugar, so the pleasurable response to pastries is partly driven by the low-nutrient carbohydrate; it’s not just the sugar that drives us. Slow down. The pivot to fall requires us to pause, reflect, and consider what our bodies truly need.

Building in the opportunity to develop more self-awareness is quite powerful at the beginning of the day too. Often, out of habit or rush, people skimp on breakfast. It’s time to break that habit. At the end of breakfast each morning, ask yourself, “How do I feel? Do I feel like I’m well nourished? Do I feel like I have enough energy now to go out and start my day and power me through to lunch?” If you pause and reflect on these questions, you might discover that you haven’t consumed a satiating breakfast. If you only had a banana, a muffin, and coffee for your first meal, you might find that this isn’t adequate. (You will find that out around 11:00 a.m. when you’re ravenous or brain-fogged.) Revisit the protein leverage hypothesis I described in chapter 3 and consider eating a few panfried eggs or sausage (or leftovers from last night’s dinner!) to power you through until lunch, stabilizing your blood sugar levels and keeping your mind clear.

A check-in with ourselves helps us curb unnecessary, problematic overconsumption (of sugar and refined carbohydrate) and also address inadequate consumption (of complete protein and healthy fats). But as is the case with everything in the pivot, the most important aspect of fall-style nutrition involves pausing, reflecting, and taking stock. This isn’t a dietary experiment in the tradition of a short-term cleanse or a “ten days to flat abs” gimmick. You are instead creating a foundation of dietary wholeness to serve you for the rest of your life, and that starts by leaving behind the old habits that haven’t served you well while creating a “new normal” for your better, brighter future.

Autumnal Movement

It’s relatively easy to accelerate the transition to sleep. Starting today, you can take a magnesium glycinate supplement before bed and hang blackout curtains in your bedroom, and you’ll start to notice positive changes. Likewise, after a month or two of autumnal-style eating, you’ll also begin to see positive effects in your life. Exercise is different. Because it involves a structural stressor, we must ease into it more gradually. Getting injured exercising is pretty ironic, don’t you think?

This approach needs to be personalized, and largely based on your individual fitness level, before pivoting to fall. In chapters 4 and 6, I described the importance of engaging in functional, strength-based movement patterns like squatting, deadlifting, ascending stairs or steep hills, rock climbing, and picking things up and ferrying them either in your arms, on your back, or in your hands. If you’ve integrated these movements into your lifestyle for a few months, then you can advance deeper into your personalized pivot. But if you’ve been relatively sedentary, or performed no strength training at all, you must develop this movement “anchor” before supplementing with the other hallmark fall movements. Please perform the anchor behavior of functional strength training described in chapter 6 for at least a month or two before you add any additional conditioning work. Go slow and easy, remembering that movement and exercise should represent mild bodily stressors that you gradually adapt to, making you stronger and more resilient over time. I’d feel like I failed to provide responsible, helpful guidance if you ended up getting hurt or even further beat up by life’s stressors as a result of starting my recommended movement plan.

In general, the pivot to fall movement represents an amplification of the anchor movements. During your pivot, do a lot of low-intensity, high-frequency movement, like walking, stair climbing, and riding your bike to the grocery store instead of driving. To cultivate a spirit of autumnal movement, start to gradually blur the lines between physically active and fully stationary aspects of your life, deliberately and proactively choosing to move and engage more of your body when you can. For example, instead of sitting still on your therapist’s couch, ask if you can walk and talk instead, or take some conference calls as you’re casually walking instead of stapled to your office chair. When you feel ready, begin integrating higher-intensity activities into your routine. Gravitate away from the long-duration summer activities of hiking, swimming at the lake, playing golf, and gardening and toward higher-intensity movements like hill sprints, intervals on your bike, or rowing (on a river or on a machine).

Generally, your movement during fall’s pivot should mark a midpoint between the extremes of low-intensity, long-duration summer activity and the short-duration, maximal intensity of winter. Do fifteen to sixty minutes of beach volleyball, tennis, or pickup basketball. Or train for a five- or ten-kilometer race, start rock climbing, take up Brazilian jujitsu, or sign up for aerobics classes. Diversifying the nature of your workouts is also central to the fall pivot. If you’ve primarily emphasized a winter-type strength-training regimen such as power lifting or bodybuilding, then you’ve already built robust connective, muscle, and skeletal tissues. It’s now time to supplement with some moderate-intensity, moderate-duration activities to build your cardiovascular endurance. On the other hand, if you’ve been engaging in chronic summer cardio, introduce some strength training, reducing your total training time and increasing the intensity. In fact, if you’re a die-hard CrossFit, Orange Theory, or Insanity participant, or religiously attend the local pseudo-military sergeant’s “boot camp” classes in the afternoons, you’ll likely work out less during the pivot (just like I did as I tapered down from my excessive reliance on training to manage my psychological stress).

Remember, if we’re using an intense exercise regimen to blunt our feelings or to self-medicate, we’re off kilter. People commonly develop addictions to intense exercise like hard running, CrossFit, and triathlons, but not to tai chi, hiking, swimming in a relaxed fashion around a lake, and gentle yoga. The first group provokes a stress response, and the second doesn’t. Notice that. The kind of exercise I’m advising in the pivot, and eventually for every season, should not negatively affect your psychological state if you skip it.

When I initially began working with consulting clients who struggled with compulsive exercise, I started hearing about their increased irritability and anxiety as we dismantled their destructive training programs. “Isn’t this healing work supposed to make them healthier and happier?” my clients’ partners and family would often ask. “He’s turning into a total jerk and picking fights with me all the time.” I realized eventually that their real addiction was to the stress response that intense exercise elicited. My clients were unconsciously addressing their withdrawal from intense exercise—itself a self-medication—through creating interpersonal stress with those closest to them. In other words, they were swapping physiological, structural stress for interpersonal stress—all the same to the body. We do this in all sorts of ways, swapping compulsive scrolling for video gaming, reading and intellectualizing in place of experiencing our difficult feelings.

We avoid and self-medicate in so many different ways, and just like exercise, some of the behaviors look “healthy” on their face, but peel back a layer, and you’ll notice that the reason you’re doing that specific thing is anything but healthy. Sure, it’s probably better to exercise compulsively than to use drugs, but the commonality is the lack of healthy, effective coping skills for unhealed pain and buried trauma. If this resonates with you, I highly recommend digging up some books by Peter Levine, Bessel van der Kolk, Alan Fogel, and Gabor Maté.2

Initially, you might experience withdrawal symptoms when it comes to cutting back on exercise (or compulsive socializing or media consumption); you might become cranky when you can’t reach for your phone right before bed or finish the day with a big bowl of sugary ice cream. Whenever we try to extricate ourselves from an addictive pattern, we’re liable to experience anything from anxiety to irritability, short-term sleep disruptions, negative moods, and a lot of resistance to the change. But remember: compulsive exercise is detrimental to your body, and ultimately a sign that you are in the throes of chronic summer stress. The healthy solution to anxiety or depression is not more stress from excessive exercise, though moderate exercise can be a powerful tool. The extrication process might prove psychologically or physically challenging in the short term. But you can rest assured that you are making a deeply healing choice as your body adjusts to a more nourishing baseline that can sustain you into a vibrant and robust old age.

Fall-Focused Connections

Whether it’s exercise, nutrition, or sleep, so much of the fall pivot involves decelerating from summer’s frenzied, topsy-turvy pace. Connection follows the same pattern. Cultivating fall-style connectivity begins with slowing down and reconnecting with ourselves, whether that takes the form of mindfulness meditation, introspection, psychotherapy, or journaling. Sift through the fairly superficial social connections of summer and (re)establish a more profound connection with you. As in other areas, the pivot to fall should represent an opening—a cracking of the door. Your goal is just to feel more and to look more directly at larger questions about yourself, your connections, and your larger place and purpose in life. You likely won’t answer such questions after several months or even several years. This is a lifelong process, and your pivot to fall’s deeper connections is the critical first step. If you don’t eventually leave chronic summer behind, you won’t have much of an opportunity to explore some of these bigger, deeper topics, and your long-term sense of peace and belonging will suffer.

Make some room for yourself by double-checking on your social engagements. Just as you ask yourself whether you really need dessert, ask yourself whether you really want to attend happy hour every Friday night with your colleagues, or if you really want to host a birthday party for everyone in your daughter’s class next month, or if you need book club and your weekly basketball league games. Declining some of those social opportunities allows you more time to reconnect with yourself and even your closest friends and family. Another way to socially decelerate is to start recognizing sources of gratitude and recording them in a journal. I used to roll my eyes when I heard people talk about such journals, dismissing them as soft, fluffy, even contrived and self-indulgent. But I don’t see it that way anymore. Gratitude journaling is a simple, effective mechanism to notice and connect to a deep sensation of appreciation and gratitude—both hallmark emotions of fall. Of course, you don’t have to journal to express gratitude (it simply helps you to notice the things you might be grateful for); you can simply express gratitude as you feel it, to other people, to yourself, to a higher power or to mother earth if that fits your belief system.

In the context of your fall pivot, take some time for other self-care activities dedicated to your personal restoration. Once we start to slow down and notice our needs, a series of helpful self-care activities will often come into focus. They might include the stereotypical bubble bath and glass of wine, rising ten minutes earlier in the morning to meditate or read, or getting a massage every few weeks. These activities need not be expensive nor time intensive. For me, the most important of such activities is meditation. Meditation is the ultimate self-care practice, and a powerful way to be more present and grounded. It’s therefore optimal to start during the pivot. I recommend Eckhart Tolle’s profound book The Power of Now and Dan Harris’s Meditation for Fidgety Skeptics as starting points. The apps Headspace and Insight Timer are both excellent meditation tools too.

Pivoting to fall also involves connecting or reconnecting to place, people, and purpose. Whether literally or metaphorically, we’ve spent our summers preoccupied, busy, and traveling—maybe working our butts off on the job or distracting ourselves with Netflix binges. In the spirit of autumnal deceleration and reconnection, think about spending more time settling in at home, decluttering your surroundings and possibly even revamping the decor while you’re at it. Reconnection to place might also involve returning to your family roots, to your hometown. As I’ve observed after two decades of living in America, Thanksgiving is one of the most emotionally powerful holidays. It’s the archetypal autumn celebration that honors familial rootedness. Seek that emotional tone throughout your metaphorical fall.

Whether we return home or not, this pivot means reinvesting in and prioritizing our anchor connections. For many of us, these close connections are parents, siblings, children, aunts, uncles, and cousins. For those without such close familial relationships, our anchor connections might be our closest friends or other members of our “chosen family,” such as committed romantic partners. These are the deep, intimate, profound relationships that are stable over time and resilient through difficulties. As I’ve discussed, reconnecting with our anchors or establishing new ones can be awkward and even discouraging because we make ourselves vulnerable to the rejection of others. But fall’s directional shift from numerous, more superficial connections to fewer, higher quality ones requires that we lean into the discomfort. That is a move that will take time, energy, and courage.

Begin this reconnective process by checking in on the quality of your relationships. Ask yourself: In what ways are my relationships deep and meaningful? In what ways are they superficial or emotionally distant? How can I bring some of these people closer? Could an acquaintance of mine become a closer friend? Could I connect with my dad in a more profound way? Maybe you could invite your basketball friends to have dinner with you and your family, instead of leaving promptly after your weekly games. Reconnection involves exploring these topics and following up with deliberate and proactive action.

Our chronic summer society encourages superficial and mostly fun modes of connection, so be prepared for people to express a little confusion or discomfort when you open up to them or invite them closer. Part of this pivot is learning how to part with your defenses, frustrations, or past hurts and to speak with more openness and vulnerability to others. “We haven’t talked much these past few years,” you might say to a faded anchor connection. “We ended things with a fight, and I’m ready to put that behind us and reconnect.”

Also remember that the fall pivot is a moderate, transitional step. We’re not engaging in summer partying, but we’re also not only having friends over for an intimate fireside chat in the deep of winter, discussing our existential dilemmas and most profound insecurities. Instead we’re deliberately moving toward reconnection in a healthy, experimental fashion. This shift takes time and practice, and fall is the perfect transitional time.

As I discussed in chapter 5, a reconnection to purpose, place, and self are integral parts of this process. The fall pivot provides a great opportunity to check in and reassess the direction of your life, considering whether you are on the right track in your career, friendships, marriage, and even finances. So much of chronic summer society hinges on consumption, and an almost insatiable desire for acquisition, a constant yearning for more. Part of reconnecting to purpose is checking in with yourself, possibly with a close friend or loved one, to help you explore profound questions. Ask yourself: Do I have enough? This is a particularly potent question to ask after doing some gratitude journaling and noting all that you do have. Give this some careful thought and consideration, because society’s default assumption is that we never have enough. Even if you have a gratifying job, pay all of your bills, and want for nothing, you’ll still likely feel the need for more. More money. More recognition at work. More toys. More square footage in your house. More retirement savings. That’s the mantra of chronic summer: more, more, more. Consider prayer, meditation, introspection, and journaling as important strategies for questioning our society’s default mode of endless acquisition and for identifying your truest desires.

One of the challenges of being in a perpetual summer mode is that we never acquire true knowledge of ourselves, either. Our extrication from the outward focus and consumption of chronic summer includes self-examination, gleaning valuable self-knowledge through inward-looking, quiet, and sometimes solitary experiences. Summer’s consumptive mode is necessarily future oriented, urging you to work harder so you can acquire more things, like a bigger house, an exotic vacation, and an elite education for your kids. Mindfulness, by contrast, entails clearly seeing and experiencing what is happening now. The “enoughness” and adequacy of fall often involves being profoundly present. And who knows: your innermost longings and true life purpose might arise spontaneously as you focus on the moment, exploring what you want out of life and whether your current actions match your values.

Take parenting, for example. Parenting might constitute a big chunk of your life purpose. Or, on closer reflection, you might feel that intensive parenting has displaced some greater purpose you have. It’s easy to lose ourselves in the parental roles of provider, protector, teacher, nurturer, and chauffeur. There’s great beauty in sacrificing your quality of life, time, or energy in the service of your kids; the disconnect happens when parents make these sacrifices out of guilt and social expectation rather than a deep calling. Strike a balance between honoring your values as a parent and honoring what’s important to you as a person. You’ll be setting a great example for your children by showing them how you take care of yourself and find balance among life’s many competing demands.

It’s essential to recalibrate this balance throughout our lives because chronic summer overstimulation can numb our deeper yearnings for purpose and meaning. That might even be one of the reasons that we seek out the numbing stimulation—to drown out the unaddressed, gnawing recognition that there is something bigger out there for us. Pivoting to fall provides an opportunity to embrace a more philosophical and introspective mode. This may sound idyllic or romanticized, but often the revelations that arise from these slower, quieter activities are, in fact, deeply unsettling, discouraging, and disorienting, leading us to question some of the fundamental premises about the way we view the world, our personal values, our relationships, spirituality, or the ultimate nature of consciousness. The fall pivot might also be a time of grief and sadness, of the deeper recognition of past losses, leaving you feeling more disoriented than you did in summer. This is one of fall’s central challenges and paradoxes: we are more deeply connected to ourselves, our anchor connections, and a sense of place and purpose during this season, yet we often simultaneously feel solemn, discouraged, and might feel a downturn in our mood. It’s a paradox we feel keenly at first, as we withdraw from the numbing stimulation of excessive summer.

However uncomfortable or unfamiliar these feelings are, experiencing more of them is a positive sign. As we notice the grief, sadness, and loneliness that we’ve drowned out in our chronic summer frenzy, we can explore the source of these feelings, and begin addressing them. Maybe we need to explore a childhood trauma in therapy or address a spiritual yearning we have through meditation or prayer. Or perhaps we deeply desire a committed intimate partnership that we don’t currently have and need to make some shifts to make room for.

Sometimes this process allows us to push beyond our long-held beliefs and automatic assumptions, and to connect with our more profound inner yearnings. For most of my twenties and thirties, for example, I identified as a hard-line atheist, believing there was no deity or supernatural reality of any sort. But following the introspection and self-evaluation I did during my incremental fall pivot and extended therapeutic winter, that perspective has begun to soften somewhat. I’ve moved away from a strident position of knowing what I believe to a more flexible space where I’m open to a variety of different spiritual possibilities. I don’t really know what I believe, and that’s okay. Just broaching those questions has made me more open, compassionate, and self-aware, and has been deeply rewarding and meaningful. Spirituality is one of many ways we cultivate meaning and purpose, and as I’ve explored this previously unknown dimension of myself, I’ve experienced enhanced meaning, and that has fueled the trademark fall feelings of gratitude, abundance, and generosity. This whole cluster of profound and interrelated experiences wouldn’t have been possible without my deliberate slowing down and peering within as part of my personal pivot to fall.

That’s part of the beauty of fall. It’s a transitional period, allowing us to make way for the emotional intensity and presence of winter. Then, once spring comes around again, we can experience more outward-directed energy, intensity, and zest—feelings we haven’t had much of lately because of our chronic, exhausting summer. Grief, sadness, discomfort, and recognizing things that you need to let go of are typical of fall. Fall is a time of stripping away, of lightening one’s psychological and emotional load, and this letting-go process can invoke sadness that we are unaccustomed to feeling (given how much time and effort we spend avoiding discomfort in our collective chronic summer). But fall also catalyzes self-discovery, an enhanced feeling of purpose and contribution, and even the wonder and awe that can arise from mindful meditation or a spiritual practice. Lean into all of those feelings, as they in turn enable the beautiful renaissance of spring and our reemergence as strong, fertile, capable people. As powerful as a fall pivot can be, three months of moderate fall won’t undo the consequences of years or even decades of chronic summer. That’s why, following our pivot out of that unnaturally long paradigm, we must embark on an even more therapeutic and restorative phase of metaphorical winter—the true antidote to chronic summer. Winter is a powerful medicine for our summertime ills.

Winter Heals

As a season of profound recovery, therapeutic winter is grounded in restfulness and sleep. You can think of winter sleep as a recovery period from an illness, literal or metaphorical (or both). Sometimes, when getting over a bad flu or cold, you might sleep for fourteen hours straight, or ten hours a day for five consecutive days. Our therapeutic winter also contains extended periods of sleep, all designed to correct for your prolonged period of pathogenic chronic summer. Experiment with dimming your lights as early as 8:00 or 9:00 p.m. and, if possible, arise naturally with the sun. Don’t mistake this extra sleep for lack of productivity or laziness. On the contrary, winter sleep is deeply healing—and necessary.

Therapeutic winter’s nutritional staples include meat (including the fattier cuts), preserved foods, and root vegetables like carrots, beets, parsnips, and winter (hard) squashes. Winter is a great time to embark on short-term trials of low-carb/ketogenic and time-restricted eating patterns. With the consumption of high-fat, low-carbohydrate foods your body will naturally shift from burning mostly carbohydrates to relying on more stable fat and ketone sources to fuel it and your overall recovery process. As you know from past chapters, I recommend doing all your eating during the daylight hours. In the wintertime—real or therapeutic—we have fewer daylight hours, resulting in a shortened “feeding window” to consume food, allowing our body to spend less time digesting and more time healing. For optimal restoration, consume your largest meal in the morning within an hour of waking/sunrise, a smaller lunch, and a spare pre-sunset dinner. Not giving in to the after-dinner cravings will be made easier by dimming the lights (thus not sending the “be alert” signals that can cause sugar cravings) and heading to bed earlier. You don’t need to exert willpower to not snack if you’re asleep! For those of you not habituated to eating breakfast, you’ll probably find it easier to eat in the morning if you ate dinner at 5:00 or 6:00 p.m. and didn’t snack at all after dinner.

When it comes to movement, think of therapeutic winter as your rest period or (relative) off-season. This is a time to give chronic overuse injuries, like that nagging plantar fasciitis, patellar tendonitis, or lingering shoulder ache, an opportunity to heal. Expending less energy and pushing less hard enables such physiological recovery. Your anchor movement of functional strength training should remain intact, and if you feel energetic and motivated, feel free to engage in the winter-style movements I’ve described in this book like short bursts of intense movement or interval training. But here’s my therapeutic winter rule: your total time spent engaging in continuous high-intensity movement is ten minutes. That means that when you’re doing intervals, say, on a one-to-one work:rest ratio, your total time in activity cannot exceed twenty minutes. What I’m getting at here is that the total “dose” of stress is very small; that neither moderate strength training nor very short, high-intensity training induces a large hormonal stress response; that avoiding more stress is a critical feature of a healing winter.

Therapeutic winter similarly opens you to psycho-emotional healing. Because we’ve removed the excessive and superficial summer relationships, winter’s connection to self and our closest others becomes more intense (in a really good way). Winter is a time to deepen any introspection and self-awareness activities you’ve embarked on during your fall pivot. During therapeutic winter, you’ll be home and perhaps alone more, simply relaxing, reading, journaling, napping, daydreaming, and meditating. Let yourself get bored. Let your mind wander. Give yourself permission to not do things. If you didn’t start therapy or a daily meditation practice during the fall pivot, do so now. Talk about what you discover with a few close anchor connections, and go deep. As the pendulum swings the farthest away from the superficiality of summer, winter is a time for terrifying intimacy and profound vulnerability. Strongly consider going on a social media blackout during this season. I know one person who gave up his smartphone entirely for his therapeutic winter. I admire that kind of commitment to one’s own healing process. Admittedly, I struggle with engaging “just a little bit” with social media, and I foresee more offline blackouts in my future as I continue to expand my own healing into more corners of my mind and life.

Keep in mind that, especially when contrasted with the spring-summer continuum of which we’ve grown long accustomed, winter’s general vibe can sometimes feel a bit solemn. Therapeutic winter entails a natural downturn in mood, when feelings of loss and the awareness of mortality can arise. Winter is the time when the trees look barren or even lifeless, but it’s also the time when they are storing up resources to rebound into rapid growth and expansion in the spring. As a summer society, we aggressively avoid such difficult emotions, regarding them as “bad” or even pathological. When we pivot to fall and then therapeutic winter, we thus experience these submerged feelings that have often gone unresolved for years or decades. Don’t fear natural human experiences of grief, loss, mourning, and sadness. To the extent you can, embrace them. (Not to minimize truly pathological depressive conditions that must be addressed professionally; do not hesitate to seek out professional help if needed.) Winter—seasonal and therapeutic—is a normal time to process these cyclical emotions of loss, loneliness, and sadness, leaving you less burdened when you resurface in spring, lighter and clearer.

Establishing or finding a long-lost connection to purpose often comes out of deep winter’s introspection. That purpose sometimes has a spiritual component, an interpersonal or relational component, or a societal dimension. It virtually always involves something larger than ourselves. Most of the time, our most peaceful, meaningful, gratifying life experiences occur in relation to people, whether that person is us, our families, or our larger communities. Whatever your purpose in life might be, don’t rush therapeutic winter’s restoration and don’t skip past the opportunity to be present to your feelings, thoughts, dreams, and disappointments as you struggle to find your purpose and path. You’re not going to sort this out in a few weeks or even a few years, but each gleaming winter provides more opportunities to learn and deepen your connection to purpose. This evolution of self goes on forever, which I find both maddening and magical.

For some people, as I’ve mentioned, a season of therapeutic winter might be fairly brief, perhaps only a few months. Younger readers in particular might need less of a therapeutic winter, as they handle stress better from a physiological perspective and haven’t had as many years of exposure to chronic summer stimulation. They’re simply not so badly beaten down. For others, especially people with systemic inflammation, mental health struggles, or metabolic dysregulation, their therapeutic winter might last several years. Mine did, and I revived this principle for a second go-around as part of my postdivorce healing process. I’m not saying that your multiyear therapeutic winter should be a period of full-blown ketosis, minimal movement, and social isolation. It simply means that you’ll concentrate the range of activity and lifestyle variation during this period toward the winter end of the seasonal continuum, even in the actual spring and summer seasons. The fall pivot and therapeutic winter entail more of a dominant mood, feeling, or orientation, instead of a fixed set of objective behaviors. You can have a healing, wintery mind-set even if it’s hot and sunny outside.

If, for example, you are a night-shift worker or travel extensively, your body experiences perpetual circadian rhythm disruption, making fall sleep a challenge. Speaking plainly, this is a sub-optimal situation. But that doesn’t mean you can’t still do a fall pivot. Instead, it underscores the importance of offsetting an imperfect situation with even greater consistency across the other lifestyle keys, making great dietary choices and achieving consistency with movement and social behaviors. Perhaps you have an orthopedic injury like a meniscal tear in your knee or some chronic inflammatory condition that doesn’t permit intense exercise or skeletally loaded strength training. That’s all right too. During your pivot, you can work toward partially loaded (scaled) body-weight movements, or even stand up and down out of a chair a few times. Do what you can and build from there. This is a very flexible system that you can start using no matter where you currently are.

Maybe your schedule is chaotic, you’re experiencing financial difficulties, or even grappling with mental illness. You can modify my prescriptions accordingly, working around certain parameters and customizing others. It might take you several years. Some readers might have dedicated years to eating healthy, developed a strong sense of self-knowledge and self-efficacy, and have a supportive close-knit group of family and friends, but might have changed jobs, relocated their families, embarked on new career paths, had a child, or returned to school. These external circumstances also pose challenges, none of which are insurmountable.

I’ve had hundreds of consulting clients over the years tell me that they couldn’t possibly curtail their intensive exercise routines. “It’s good for me,” they say. “It’s camaraderie at the gym. It’s social connection. It’s stress relief. It helps me sleep better. It manages my weight!” How could I possibly deny them something that has so many obvious benefits? It’s a fair question, but it also requires that we examine the underlying motivations, which always end up being more important that what the tangible behaviors are. In these cases, these clients were often rationalizing and defending their addiction to intense and excessive exercise, mounting resistance to a more moderate regimen of fall movement. As anyone who has ever dealt with addicts understands, they are masters of justifying the addiction and denying that there is a real problem. I can say that; it takes one to know one.

Some of my clients have pushed back on my food recommendations, saying that they can’t fully get on board with my food plan because the organic, seasonal, sustainably raised food I suggest is elitist, unrealistic, or too expensive. Others protest that they need a steady drip of all-day caffeine to keep themselves awake during work; or that they can’t part with their cell phones at night because the work taskmaster expects them to be available twenty-four hours a day. There are many challenges that people might have with these changes, some of which are fully valid. We all must pay our bills, and if you absolutely must do overnight shift work to do so, then there’s no way around that. Sometimes, however, people will say my dietary plan is too expensive, but nonetheless spend $400 a month to lease a high-end car and $150 for cable television. Affording the optimal food in this case is not a financial limitation, but not a priority relative to other consumer items. It’s a statement about personal values. There’s no judgment inherent in that; only you can determine what’s most important to you. Oftentimes, resistance to changes masquerades as a pragmatic limitation. That resistance often really covers up a fear of failure, discomfort with the unfamiliar, fear of social rejection or judgment in being unconventional, or feeling alone and unsupported by your family, friends, or partner. If you’re pushing back against some of my recommendations, check in with yourself and ask what the “but what if _________” concern is. I bet it’s there somewhere. Sometimes, simply identifying what the fear is helps you to move through it.

But whether you are internally resistant or openly enthusiastic, think of the fall pivot and therapeutic winter as a series of self-directed principles and concepts, not pass/fail propositions and rigid rules, that, taken together, trend toward deceleration, restoration, contraction, and reconnection. The more you embrace these principles and the more broadly you apply them to your life, the smoother and more gratifying of a transition, and future life, you’ll ultimately lead.

Once I got past some of my own internal resistances, I greeted fall with relief. I fell into it like a child falls into the comforting arms of a parent. Chronic summer living often felt like I was speeding—recklessly—on the freeway. Sometimes the feeling was momentarily exhilarating, but it was also scary and uncomfortable, as I thought about aggressively slamming on the brakes, swerving, or losing control and careening off into the ditch. The safest and best way to adapt in such circumstances is to simply take your foot off the gas, flick your turn signal, and deliberately move to a slower lane. That first moment of deceleration is immediately calming and reduces your stress response. But notice, you’re not screeching to a full stop on the freeway, and you are still in the car on a journey. This figurative deceleration creates an opportunity to inhale deeply and recognize you are shifting in a safer, more positive direction. Like slowing down to a safer, less reckless speed on the freeway, moving into fall gives you more control, safety, room to breathe, time to think, and, ultimately, peace of mind.

Living the Pivot

Do you remember Kim from chapter 1? She was the woman in a familiar rut who bathed in blue light as she tried to fall asleep, engaged in unhealthy movement patterns, and managed only a subpar marriage and so-so relationship with her kids. I have some great news about Kim. I introduced her to the concept of anchors, and she spent a few weeks establishing important dietary, sleep, movement, and social foundations in her life. With those foundational anchors in place, Kim then embarked on the pivot I described in this chapter. She became really consistent in avoiding blue light in the evenings, and instead reads a (print) book of poetry she keeps on her nightstand. She bought a light alarm, allowing her to wake up more naturally and in step with the natural light. She sets it for fifteen minutes before she needs to wake up, so she can take some quiet time to wake up gradually and enjoy a few pages of poetry as she eases into the day.

Once she’s up and rolling, her first priority is locating an anchor of complete protein for the family breakfast. Starting the day with protein has given her more energy and a more stable mood. She also purchased a monthly box of produce, commonly referred to as community supported agriculture (CSA), and now eats an array of seasonal fruits and vegetables. It’s taken some work and occasionally some research. Kim has found herself with unfamiliar produce on several occasions and had to go online to learn how to cook turnips, rutabaga, and acorn squash, but she’s enjoyed the adventure of cooking and eating new foods. With this concentration on local produce and dietary proteins, her household consumption of refined grains and dairy has decreased substantially.

Kim’s work schedule is still demanding, but after she ditched her high-intensity workouts and instead focused on movement anchors, she’s become much more at ease and happy. She met a few girlfriends at the gym and decided to host them every other weekend for an informal brunch. Nothing fancy—she simply decided to take a risk and draw people with similar experiences and lifestyles closer to her. Her desire for closer, meaningful connection also extends to her husband. Kim and Mark’s marriage wasn’t in crisis, but they’d been disconnected for a while. After a few conversations, they decided to enter couples’ therapy in a proactive attempt to communicate better and connect more deeply. Though they found it a bit awkward communicating before a third party at first, their communication started to improve, and this extended to their physical intimacy as well, and they were both grateful for the experience. Kim and Mark still have their own interests, and they allow each other space to pursue them. But when they do connect, they have more fun—like they did during their marriage’s early days.

Paying more attention to each other led Kim and Mark to focus more on their kids. They instituted a very unpopular “no devices at the dinner table” rule, and it was a headache at first. But they led by example, not checking their phones as they talked to each other. As they became more present with each other, they were able to engage in more meaningful conversations with their kids about what was going on at school, and with their friends. Soon, the grumbling about the phones subsided.

Kim’s reconnection has also extended to herself. Like many mothers, she’d lost touch with herself in the chaos of parenting. To recalibrate her life, she established a daily, fifteen-minute mindfulness meditation practice first thing in the morning. It was a small lifestyle adjustment, just like her morning poetry reading. But both of these activities have made a big difference, as Kim starts her day feeling centered and creatively nourished, and now feels less frayed, anxious, and fragile.

Three months following her fall pivot, Kim and her husband embarked on their more intensive, immersive experience of therapeutic winter. They naturally started winding down even earlier in the evening. They stopped watching television altogether and moved all phones and non-analog devices from the bedroom, choosing instead to illuminate their space with salt lamps and sometimes burning candles. This increased the comfort and intimacy of their room, and also dimmed the light spectrum, helping them achieve a more peaceful, relaxed nighttime mode. Kim and her husband extinguished the candles at 9:00 p.m. consistently and fell asleep shortly thereafter.

After embracing several months of a fall-style moderate diet, Kim’s eating patterns gravitated toward even higher-fat, lower-carbohydrate offerings. She made stews, short ribs, and hearty soups in her slow cooker, stocking leftovers in the fridge or freezing them in ziplock baggies, easily accessible for lunches on the go and even filling breakfasts. Her kids initially looked at her funny: “We’re going to have meat stew, for breakfast?” But they grew accustomed to the change, and now instead of thinking of cereal, waffles, and orange juice as breakfast food, they have a broader and richer understanding of food in general.

As Kim’s mindfulness meditation practice progressed postpivot, her self-knowledge deepened in turn. During her fall pivot, she’d experimented with erecting boundaries, sometimes telling her children that she needed to redirect their energies when they asked for a late night at the amusement park or arcade. But during her more intensive therapeutic winter, she had more profound realizations about the nature of human boundaries themselves. Prior to this journey, for example, she’d believed that creating boundaries was a defensive or aggressive act. Psychotherapy and meditation, however, led her to understand that boundaries serve to more clearly articulate and define the borders of self. Over the span of fifteen years of marriage and parenting, she realized that the boundaries between herself and her family had blurred, leading her to neglect important self-care and lose sight of her life’s purpose.

Armed with these realizations, Kim started carving out more time for herself and began maintaining healthier boundaries with her family and her children. Her morning meditation time became fixed and sacred. She also drew her anchor connections even closer. She and Mark committed even more to couples’ therapy, exploring profound topics that made them feel close, connected, and intimate (though also more vulnerable and exposed than their fall sessions). The kids started relying less on their phones and exploring more creative pursuits. Kim’s daughter expressed an interest in taking art lessons, and Kim began drawing and painting herself, becoming closer with her child in the process.

Overall, Kim is more emotionally stable and present for her kids, her husband, and herself. She hasn’t lost copious amounts of weight—in fact, the scale reads the same as it always did—even though her clothes fit her better. Feeling more settled in her life, she’s proactively advocated for herself and her own interests, choosing to stay in and connect with people over homemade meals or brunches instead of going out for drinks. She also declined to take her children to the water park one weekend, telling them instead that she needed more family time with them (and more time with herself). She did this lovingly, without aggression, modeling for her kids how to establish healthy boundaries, even when it came to them. Ultimately, for Kim, this six-month period of movement away from chronic summer has given her more rootedness, control, and sense of connection.

In many ways, Kim’s fall deceleration and embrace of winter restoration is far from revolutionary. Over the course of the twenty-first century in particular, our society has begun to realize it’s collectively disconnected, lost, and frayed at the edges. Many studies, for example, have drawn attention to the importance of prioritizing sleep. There’s a larger cultural conversation around how sleep is deeply restorative, and integral to one’s mood, mental health, cognitive performance, and longevity. People have started to pay more attention to sleep hygiene, wearing blue light–blocking glasses to work on their computers at night, and even avoiding screen time altogether before bed. And that’s a step in the right direction.

The importance of healthy, nutritional eating has also broadened throughout our society. When the Whole30 program began crystallizing around 2009, it formed part of a larger movement of popular nutritional awareness, during which people began experimenting with plant-based diets, low-carbohydrate or ketogenic diets, and seasonal, local eating. And while we know junk food is bad, it’s also common knowledge that sedentary lifestyles are just as unhealthy. At this point that’s as ingrained as knowing that cigarettes are bad for you. Sedentary lifestyles, we’ve been told in many forms, have profoundly negative effects on our quality of life. We’re also aware that conventional aerobic exercise and the type of chronic cardio I describe in this book isn’t the best alternative to no movement. In fact, a broad cross-section of North Americans now understand that summer modes of intensive exercise don’t create durable bodies that endure into old age. Gyms, personal trainers, and wellness-inclined individuals have begun featuring bodybuilding exercises, step aerobics, and kickboxing, realizing that our long-term structural, metabolic, and mitochondrial health greatly benefit from such activity.

Around 2010 or so, I began noticing a lot more cultural conversation around the value of human connection. Sherry Turkle’s Reclaiming Conversation and Susan Pinker’s The Village Effect join other books in addressing our society’s disconnection, loneliness, and overstimulation. Many of us have started realizing that even though we have many “friends” on social media, we still feel lonely. Even technology company executives have put limits on their children’s screen times, and app developers have created tracking software to give us awareness about how much time we spend on them. Many of us are startled by how addictive our screen-based entertainments and habits are. We now understand that the social isolation and disconnection that social media breeds are huge risk factors for anxiety, depression, and other forms of mental illness, and we actively limit our screen time, downloading tracking apps on our phones to curtail the time we spend mindlessly scrolling our social media feeds.

As someone whose life purpose centers on health and human wellness, I’m inspired by these positive trends in our society. I’ve personally experienced how such shifts in lifestyle behaviors have profoundly improved my life, and those of my clients. But what I’ve also noticed is that however beneficial such isolated and piecemeal lifestyle changes can be, they alone don’t produce enduring change. In fact, I’ve observed the opposite, where people discover ketogenic eating, or high-intensity interval training, or engage in social media detoxes, and believe they’ve found the answer to all the problems that ail them. Unfortunately, these positive changes begin to peter out months or years later, after which time people often double down on the same strategy (pursuing keto with even more ferocity and dedication), or try another isolated strategy, considering the previous one a failure. What makes my model unique is that it combines and coordinates these various principles into an integrated and oscillatory pattern. If you pursue the restorative, health-promoting lifestyle behaviors over seasons, in a coordinated fashion, you’ll make lasting, lifelong changes.

But in order to experience the cognitive, physiological, and psychological benefits of seasonal living, we must first embark on a period of restoration. So please: whether you’ve read books on sleep, tried the Paleo diet, or even actively engineered your biological circadian rhythms around morning light and evening blackness for optimal sleep, don’t skip this step. After you establish your anchors (see chapter 6), lean into your fall and winter periods in a prolonged, focused, and comprehensive way.

I can personally attest to how indispensable these six months are. Around 2006 and 2007 I started making changes around my food, and around that same period, I also began moderating my exercise. It was a powerful improvement and I felt better. But it wasn’t until I emerged from my therapeutic winter that I really began to feel differently. I embarked on this after my fall pivot, following a period of intense travel, work-related stress, and a divorce. I felt overdrafted and withdrew. I attended fewer social events, dramatically reduced my exercise, slept a great deal, and consumed more fat-rich and hearty foods, naturally curtailing my carbohydrate intake. After decades of a chronic summer, I felt like an injured and sick animal who crawls into a dark hole somewhere to rest and recover.

It was a solemn and hard period, but it wasn’t depressing; in fact, it was a period of great clarity, punctuated with moments of joy. Prior to my fall pivot and therapeutic winter, I’d been doing a lot of travel for public speaking. During this period of restoration, I gave myself permission to decline most of these invitations, accepting 10 or 20 percent of those I previously had. Winter’s contraction gave me the clarity to understand I needed less travel, and traveling less helped fuel this recovery. Embracing therapeutic winter’s spirit of contraction was honoring the deep yearning I had to slow down, nest, and reconnect, especially with my primary anchor connection, myself.

I started introspecting and asking personal values questions like, “What is important to me? What do I care about? How do I want to show up in the world?” Though this time was dedicated to personal growth, as I sought to find my purpose and place, I didn’t become a hermit, nor was I completely sedentary. But I did strip back my exercise to the anchors of functional movement and strength training—a few pull-ups and push-ups and moderate-intensity squats—interspersed with walking and light hiking. That was a way for me to maintain basic capacity without increasing stress. I was able to find a much greater sense of peace, quietude, and restfulness in the solitude of my meditation practice, and in the company of my more intimate relationships with close anchors. I simply embraced the opposite of chronic summer, leaned into the healing, and emerged with more clarity, enhanced purpose, and greater energy.

Remember that the joy, reward, and pleasure that therapeutic winter provides is fundamentally different than that of summer and spring. It brings deep satisfaction, healing, and the promise of a better life. It’s like going to sleep after you’ve been exhausted for days. You wake up not feeling spring or summer’s sense of exhilaration. Instead you feel the quiet energy and bountiful restoration that a great night of sleep provides. I encourage you to embrace a pivot to fall and therapeutic winter like me and “Kim,” approaching your life and wellness in a targeted, comprehensive, and healing manner, enabling you to get out of chronic summer’s debt and embark on sustainable seasonal living. This period of restoration is worth it. Once this healing is over, you’ll emerge on the other side, ready for spring. You’ll have restored previously tapped-out energetic resources, fueling yourself for the psychological, physiological, emotional, creative, and relational expansion and growth of springtime.

After a prolonged foray into your therapeutic winter, you’ll naturally start to feel the telltale markers of spring-style behavior—you’ll start to feel antsy and spontaneously energetic. Look for those trademark feelings of spring: curiosity, excitement, anticipation, optimism. They often coincide with the literal dawning of seasonal spring. Your mood will lift, your energy will rise, and suddenly, your interests might pique when a friend suggests a road trip, or you might have thoughts of starting jujitsu, rock climbing, or composing music again. The visions, plans, and dreams that have been hibernating and incubating during your fall pivot and winter healing may begin to surface, and you might want to return to school, pick up an old hobby, sport, or activity, or expand your social circle.