Chapter 8. Type

What You Don't know can Hurt You

|

If you're like most people, the first time you used a word-processing application, you accepted the default Times New Roman 12-point font and never looked back. If you still treat your computer like a glorified word processor, you're not taking advantage of the full communicative and creative power of type.

The best designers are experts in type and typesetting because they understand that well-styled type not only sets the document's tone but also directly impacts its readability, legibility and visual hierarchy. Failure to follow best typesetting practices, at best, can leave your audience with a negative impression and, at worst, can leave you with no audience at all.

This chapter talks all about fonts, including styling them for both function and decoration.

|

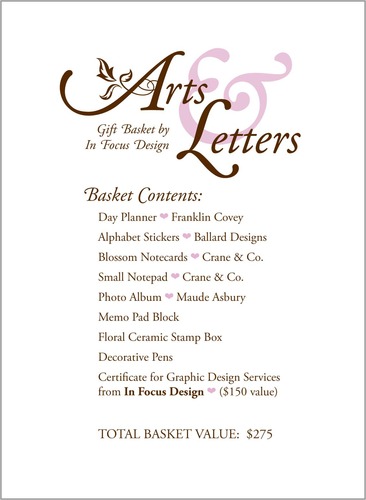

| Type sets the tone. Well-styled, properly set type sets the overall tone of the layout. It impacts readability, legibility and visual hierarchy as well. |

Font, Typeface, Font Family, Glyph

To begin at the beginning, a font is a complete set of characters in a particular size and style of type. This includes the letter set, number set and all of the special characters you get by pressing the shift, option or command/control keys.

A typeface or font family contains a series of fonts. For instance, Times Bold, Times Italic and Times Roman are actually three fonts, even though people often refer to one entire font family as a font.

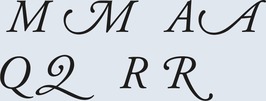

A glyph is an individual character of a font. Glyphs are not limited to upper – and lowercase letters. There are glyphs for punctuation, glyphs for special characters such as copyright and trademark symbols and even glyphs that are purely decorative. Most fonts have a set of 265 glyphs. Fonts in the OpenType® format, a format created jointly by Microsoft and Adobe, are cross-platform and can have as many as 65,000 glyphs.

Font Categories

In the same way we organize plants and animals into genus and species, we can organize fonts into categories. The shape of a font's glyphs determines its category. Learning to recognize and identify font categories is an important first step in selecting the right font for the right job. As usual, it comes down to training your eye to see subtleties.

Depending on the source you consult, you'll find many different font categories. We'll stick to a few of the most common and offer general recommendations for their use:

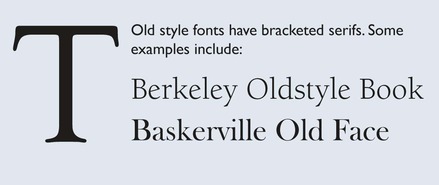

Old Style & Transitional

Characteristics

Classic and traditional, old style fonts have serifs, little “feet,” at the tips of glyphs. Old style serifs are bracketed: They start thick and taper to thin at an angle, creating little triangles. Old style fonts also contain thick stem strokes and thinner hairline strokes, though the difference between the thick and thin is not extreme. Old style fonts often have diagonal stress, which means that a line intersecting the thinnest parts of O-shaped glyphs is diagonal.

|

| Classic. Old style fonts lend a classic, traditional feel to layouts. They are the best font choices when you want readability in print layouts. |

Transitional fonts evolved from old style and share many of the same characteristics. Transitional fonts have serifs as well as thick and thin transitions. The biggest difference between the two is that the diagonal stress is missing or not as prominent in transitional fonts.

Because they are so similar, throughout this text we refer to both types as simply old style.

Best uses

For print body copy, old style fonts are the most readable. Larger bolder versions can work for headlines. But old style's hairline strokes and tapered serifs can get lost when reversed.

Serifs and fine strokes also get lost on computer and television screens. On-screen, old style fonts are best when big and bold in headlines or other short bits of copy.

|

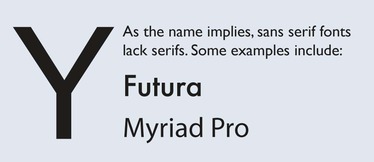

Sans Serif

Characteristics

Contemporary in style, sans serif (French for “without serif”) fonts have no serifs, and their strokes have uniform thickness. Sans serif fonts come in a variety of shapes and sizes from very round to tall and narrow to almost square.

Best uses

In print, sans serif fonts are best used for headlines and other quick nuggets of text such as sidebars and cutlines. They work well when reversed.

On-screen, sans serif fonts rule in the readability department. Many of the most readable on-screen fonts are sans serif, including Helvetica, Verdana and Arial. Larger, bolder versions make excellent headings and subheadings.

|

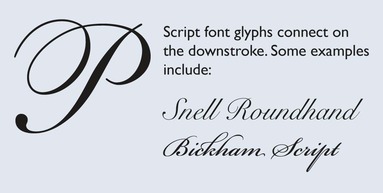

Script

Characteristics

If the type style looks like it belongs on a wedding invitation, it's most likely a script font. Script fonts tend toward formality and often resemble old-fashioned penmanship. Like cursive writing, the glyphs in script fonts tend to be connected on the downstroke. As a whole, script fonts can be difficult to read, though some are more readable than others.

Best uses

Because of readability and legibility issues, script fonts are best limited to small amounts of copy in both print and screen applications. Individual characters of script fonts make interesting decorative elements in watermarks and logos. They also make beautiful drop caps.

|

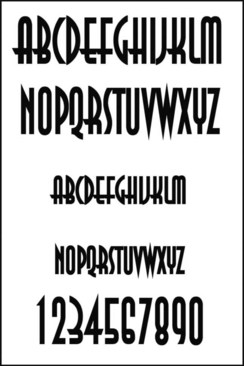

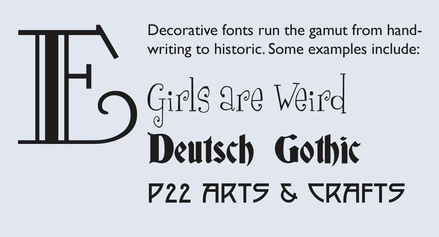

Decorative

Characteristics

The characteristics of decorative fonts widely vary. They can resemble hand lettering, vintage type, grunge type or whimsical lettering.

Best uses

For both print and screen applications, limit the use of decorative fonts to headlines, decorative details, ornaments or very small amounts of type. They are not a good choice for reading extended copy. Reversing decorative fonts may or may not be a good idea depending on the thicknesses of the parts of each glyph. Fonts with fine detail do not reverse well.

|

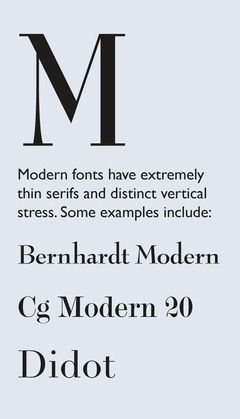

Two other common font categories include modern and slab serif. Many people have a hard time distinguishing these styles from old style fonts. The trick is to look closely at the shapes of the serifs.

Modern

Characteristics

Modern fonts have extremely thin serifs, and their stress lies on the vertical, unlike old style's diagonal stress.

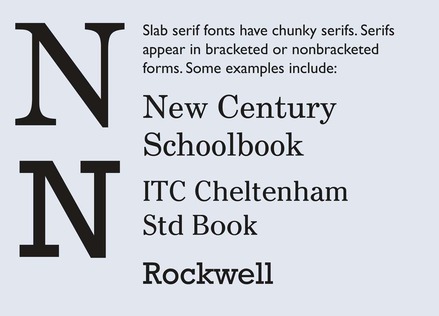

Slab Serif

Characteristics

Slab serif fonts are similar to old style fonts, but the serifs in slab serif fonts start thick and stay thick. Some slab serif fonts look like a hybrid between an old style font and a sans serif font. The result is sort of a sans serif with fat serifs, if you will.

Best uses

Slab serif fonts were invented for retail display advertising so they work well in print headlines. Some slab serif fonts can work for body copy, but old style fonts are generally a better choice. Slab serif fonts tend to work a little better in reverse because of their beefier serifs.

Slab serif fonts also work for Web and television but in the same limited way as decorative fonts.

|

Choosing & Using Fonts

Understandably, most graphic designers love fonts. We want bumper stickers that say, “The one who dies with the most fonts wins.”

Once you discover the big wide world of fonts, it's easy to go nuts. But. Please. Resist. This. Urge. Nothing screams “amateur” louder than using too many competing font styles.

1. Choose one readable font for your body copy. Make sure this font is from a larger typeface that includes related fonts with different styling. For example, for print purposes, Adobe Garamond Pro is an excellent readable body font. Plus, Adobe Garamond Pro Regular is part of a larger Adobe Garamond Pro typeface that also includes bold, italic, semibold, etc. By nature, all the fonts in a typeface get along visually because they're related. Working within one typeface allows you tremendous flexibility. You can use the regular font for body copy, the italic font for cutlines and the bold version for subheadings, all while keeping a consistent unified look.

The same principle applies to fonts on screen, though sans serifs are the best choices for readability.

|

| Be consistent. When designing any type of layout, limit yourself to one or two font families. Limiting font choices creates unity and prevents visual clutter. |

For achieving both consistency and variety, choose a typeface that includes many individual font variations, such as Verdana.

2. Choose a second contrasting font for headlines. If you choose an old style font for body copy, you can pick a contrasting headline font from almost any category. Think of old style fonts as the “basic black” of fonts. They go with everything. Your headline font, then, can be wild and decorative, script and elegant, or sans serif and ultra hip and still work. Or you could choose a headline font from the same typeface as the body and create your contrast through point size or weight. However you do it, you want the body copy to contrast with the headline.

Sans serif fonts are also rather neutral and play nicely with other fonts. Make them your go-to fonts for the screen.

Pairing decorative fonts together is almost always a bad idea. They compete with each other. Script fonts have the same problem. Think of decorative fonts and script fonts as the divas of the font world. You just can't put the two of them in the same dressing room.

Modern and slab serif fonts also can be problem children. Since modern and slab serif fonts are similar in shape to old style fonts, they may not have enough contrasting elements to make them stand out as distinctive from the body copy. When using modern and slab serif fonts, trust your eyes. If the pairing looks like you've simply made a font error instead of a deliberate design choice then the pairing isn't working. You might be able to make such pairings work if you apply contrast in another way by varying size, weight or color.

Wrong. While each of the fonts used below is 10 points, each takes up different amounts of vertical and horizontal space. For most old style fonts, 10 or 11 points is a good baseline reading size. For other fonts, use your judgment when picking the perfect size between mousetype and horsey.

|

Applying Additional Font Styling

Choosing the right typeface will give you the option of using bold, italic, semibold and other type styling options. Your software should allow you to apply some additional font styling options such as leading, kerning and tracking adjustments to impact your design's readability and visual appeal.

Font size

In your typesetting workflow, choose your fonts first, and then choose your font sizes. Layout programs come with a default size setting, usually 12 points, and somehow 12 points is never the right size.

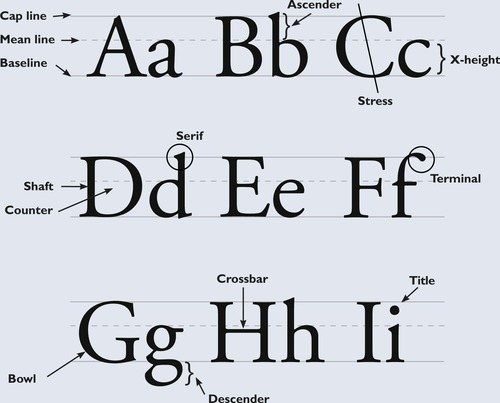

When selecting a font size for body copy, choose a size large enough to be easily readable. Start by trying a setting of 10 or 11 points, but be prepared to change the size again. Font size is calculated by measuring the distance from the top of the ascenders to the bottom of the descenders. The length of ascenders and descenders relative to x-height may make some fonts appear smaller and some appear larger. You'll have to learn to trust your judgment on choosing a font size that hits the correct note between mousetype and horsey.

Don't forget to consider your audience. If your target audience is middle-aged or older, go larger rather than smaller. The older people get the more likely they are to need reading glasses. They'll appreciate bigger fonts. Trust us.

Choose font sizes for such things as headings based on both readability and contrast. Headings must contrast with body copy, so make them really contrast. A 12-point heading barely contrasts with a 10-point body copy font; a 36-point headline greatly contrasts.

Bold & italic type

Back in the day, using all caps and underlining were the only options for emphasizing typewritten words. Thank goodness, we've evolved. Now we have bold and italic in the toolbox.

Both bold type and italic type can create emphasis in short copy situations, such as headings, subheadings or short body copy.

Did we mention short copy situations? Use bolding or italics sparingly. Neither bold nor italic is appropriate for entire pages or long paragraphs of type. Ugh. Too much italic is hard to read, particularly on screen. And too much bold defeats the purpose of having bold at all. When there's too much of it, nothing stands out.

We also would like to point out that not all bolds are created equal. Some bold fonts are bolder than others. Sometimes a bigger font size, a different color or a different font altogether provides greater contrast than using just plain bold.

All caps

All caps are another old-school style of emphasis. They can be difficult to read in long blocks of text. As with many type treatments, type set in all caps cuts down on readability. When we first learn to read, we are taught the shape of each letter and its corresponding sound. We put letters and their sounds together to make words. Over time, our mental process shifts to the point where we recognize shapes of words without the need for scanning and adding up individual characters. But when you capitalize words, they lose the ascenders and descenders that make up their unique shapes. Every word becomes a rectangle, and our brains have to work just a little bit harder to recognize the word.

To add insult to injury, we have come to associate all caps with shouting. And nobody likes to be shouted at.

If you want to use all caps, make sure they don't interfere with your visual communication purpose, including readability.

Leading

Pronounced “ledding,” leading is the technical term for line spacing. It comes from the days of setting type by hand. Once upon a time, typesetters used a slug of lead to separate each line of type.

Today, your computer calculates leading. Every font size has a corresponding default number (a percentage of the font size) that serves as line spacing. This default number works okay most of the time. However, there are times when you need to adjust it.

|

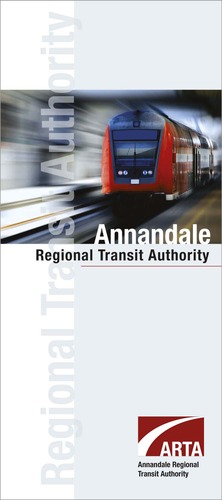

| Fine-tuning your type. Increased tracking on the headline and increased leading on the copy give this ad an open, airy quality. |

When the body copy font has a large x-height, thus reducing the crispness of the shapes of words, additional space between lines of type can improve readability. A little extra leading increases readability, too, when the body copy is set in a sans serif font or when the eye must track across a very long line of type, as in wide columns or no columns. Be careful not to overdo additional leading, as too much space also cuts down on flow and readability.

You might add extra leading for decorative purposes, too, but only for limited amounts of type because of the negative impact on flow and readability. A little extra leading can give the sense of elegance or lightness/airiness, if that serves your communication purpose. Just remember to balance it with readability and flow.

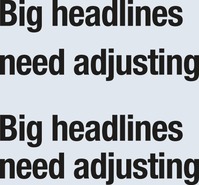

On the other hand, when creating large headlines, reducing leading is essential. Because leading is mathematically calculated based on font size, as the font size increases, so does the leading—exponentially. For headlines more than one line deep, decrease the leading to bring the lines closer together (i.e., clumping). Beginning designers often overlook this step, leaving headline gaps you could drive a bus through.

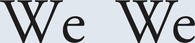

Kerning

Manually adjusting the negative space between two characters is called kerning. Most design programs are set to adjust these spaces automatically. However, you still may need to do some fine-tuning.

When uppercase letters have diagonal lines, such as on the capital W, adjacent letters may appear too far away, particularly when font sizes are large. You also may need to adjust the kerning in large headline words that begin with the capital letters T, P and F.

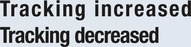

Tracking

Adjusting letter spacing across a string of characters, such as a sentence or paragraph, is called tracking. You also can manipulate tracking for decorative purposes to create tightly packed or loosely spaced words.

Sometimes tracking becomes useful for copy fitting. For example, when you have a widow at the end of a column, decreasing the tracking on that sentence may pull the lone word up to the previous line. Your reader will never notice the difference.

Adjust tracking with care. It's easy to go overboard and end up with squished text. Try to limit tracking adjustments to “-10” or less.

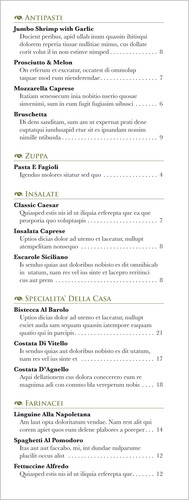

Tabs & tab/dot leaders

Sometimes, in order to keep things aligned, you need tabs. Use tabs for columns of numbers, too, and pay attention to aligning decimal places. Sometimes tabs space out farther than the eye can travel without some help. In those cases, instead of making readers' eyes do the typographic equivalent of a stunt jump across a Grand Canyon of negative space, tab or dot leaders can function like visual bridges. They assist flow by leading the eye along their line of sight.

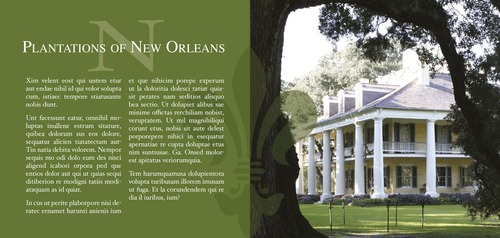

Typesetting for Extended Amounts of Copy

Page after page of nothing but boring gray words scares people, even when the words are set in a nice readable old style font. The prospect of slogging through all that reading is discouraging at best. The good news is that when the content we must communicate comes in the form of substantial amounts of copy, there are tactics for carving intimidating text into bite-size pieces.

Paragraph indicators

Paragraphs are traditionally indicated either by a first line indent or by additional leading after each paragraph. Unfortunately, most people use default tabs or an extra hard return to create paragraphs. Visually, these default keystrokes result in spaces that are too large. You need to set paragraph indents or paragraph space-afters using the specific tools for those tasks that your design software provides.

How big should the spaces be? Use your best judgment. First line indents should be consistent. They need to be just big enough to communicate their presence and do their visual indicator job, but not big enough to distract. If you choose to indicate paragraphs with the indent, remember the first graph or lead does not indent.

|

| Breaking up the gray. Bold colorful subheadings, column guides and bulleted lists break up this text-heavy document. |

Or, if you decide to space between paragraphs, don't overdo the space, but do be consistent.

Still not sure about size? Pay attention to publications around you. Educate your eye on what pleasing spacing looks like. Then use it in your own design projects. While you're at it, keep paragraph length short, as well, to hook lazy readers.

Headings & subheads

Main headers and subheads also provide a great way to break up blocks of text. When styled for contrast, headings and subheads create a sort of navigational rhythm throughout the design.

Proper spacing for headings and subheads increases readers' understanding, too. Remember to position headers closer to the content they reference (clumping) and farther away from unrelated content.

Additionally, remember that headings and subheads should indicate a hierarchy of content. As you might guess, the bigger the headline, the more important it and its related content become. By graduating the size of subheads, the corresponding copy's importance increases or decreases. Keep track of your levels of headings, along with your own decisions about typesetting them consistently.

Display fonts

If your design requires large headline sizes, choose a typeface that includes display fonts as part of the family. Display fonts are specially drawn to look proportionate at larger point sizes. This makes display fonts perfect for poster, newspaper, magazine and advertising design. The general rule is to use a display font if your headline will be 20 points or larger.

Bulleted lists

You can't beat a bulleted list for delivering information quickly and concisely. Bullets serve as eye entry points, letting the reader know in an instant that a new important idea starts here.

When typesetting bulleted lists, you have two options: either match the bulleted list with the surrounding body type or make it contrast.

When your bulleted list is embedded within and flows along with the rest of the copy, it should match in terms of font style, size and color.

If your bulleted list flows with the copy, consider indenting the whole list. You'll have to use your judgment on how much to indent. Too little and the indentation looks like a mistake. Too much and you'll have a distracting gaping hole in your layout.

If your bulleted list sits in a sidebar or is otherwise visually separated from the rest of the copy, make it contrast with the surrounding body type. For example, if your body copy is set in an old style font, consider a sans serif for your visually separated bullet list.

• When the list flows with the text, make it match the text

• When the list is in a sidebar, make it contrast with the text

• Consider indenting the entire list for additional impact

• Use “hanging indents”

• Add additional leading between bullet items for greater readability

• Choose your bullets wisely

• Don't use asterisks as decorative bullets

Whether your list is inline or in a separate box, a bulleted list requires a hanging indent. In a hanging indent, the first line of a paragraph “hangs” out—juts out—into the left margin. It's sort of the opposite or reverse of an indent. A hanging indent pushes the organizing numerals or bullets to the left and aligns all the remaining text together along a single axis.

When setting hanging indents, consider adding extra leading between each list item. The extra negative space helps isolate each item and makes it easier to digest the list. This is white space and clumping to the communication rescue.

Finally, choose your bullets wisely. You can dress up a list with decorative bullets, but as with most design decisions, just because you can doesn't mean you should. If you want a bullet with more personality, consider pulling a shape from one of the many symbol-based font sets out there. Choose something that matches the tone of your layout.

Taking a Page From Newspaper Design

For presenting extensive amounts of type in a digestible format, newspapers rule. Designers of daily broadsheet newspapers manage to lay out five or six text-heavy stories on a single front page each day, with each story clearly delineated in a visual hierarchy. Much of this fantastic feat is accomplished with typesetting.

Headlines

Headlines are the billboards of newspaper design. A well-styled headline is like a big smack on the nose that says, “Read me!” Newspaper designers are experts at creating interest and visual hierarchy through techniques like page position and font contrast.

Graduated headline sizes also reinforce the idea that some stories are more important than others. The bigger the headline, the more important the story. Headline font sizes vary, but it's unusual to see them set less than 24 points, which means leading adjustments, too, for headlines that run more than one line deep.

Another trick is to choose a condensed font for headlines. Writing news-style headlines can be tricky. They need to be pithy, but keeping them concise can be difficult. Condensed fonts are drawn to be narrower than standard fonts. Since condensed fonts take up less space, they offer an extra bit of wiggle room for copyfitting headlines. You don't need to be a news pro, either, to take advantage of that kind of help.

Columns

We keep going on about columns, but newspapers are set in columns because it's easier for the eye to track back and forth across a few inches as opposed to the width of an entire screen or page. To review, newspapers teach us that about two inches make a good-sized column width—not too wide or too narrow.

Newspapers also suggest legs of body copy ought to run at least two inches deep but no more than 10-12 inches.

Even if you don't want the look of columns in your document, you can take advantage of the principle of narrower lines of type for the eye to scan by increasing margins and decreasing line length.

Justification

One thing beginning designers should not emulate is the full justification of newspaper type.

Technically, justification refers to all forms of copy alignment, including left justified (flush left with ragged right edge), right justified (flush right with ragged left edge), centered, or fully justified (right and left edges perfectly squared).

The best justification for reading is always left justified (flush left with ragged right). It accommodates natural word spacing and provides easy eye tracking.

Type: Not Just for Reading Anymore

In addition to type tricks that encourage reading to convey information, there are type techniques that set the piece's overall tone and create visual interest. Obviously, any selection from the huge range of decorative fonts can help set mood and tone. But don't discount using more traditional fonts in creative ways. No matter which route you choose, exercise caution when using type creatively. It is easy to go from type that communicates to type that clutters.

Bold & italic

We've already discussed how bold and italic fonts create emphasis. But bold and italic fonts also have decorative uses. Both type treatments make interesting pull quotes, decks, cutlines, headlines and other short blocks of type.

Small caps

Reversed type

Reversed type is light type against a dark background. It's a common technique used in creating headlines, sidebars and other layout elements. Like all caps, it's best used sparingly. Reading a lot of reversed copy may reduce readability or tire the eye. If you expect your reader to digest significant amounts of copy, then you don't want to reduce your type's readability or tire readers' eyes.

If you choose to employ reversed type, choose your font carefully. Some fonts lose legibility more than others when set in reverse. Modern fonts, with their ultra thin horizontals are notoriously bad in the reversing department. Reversing works best with slightly thicker sans serif fonts, though slab serif, bold versions of old style fonts and some decorative fonts are equally effective.

Initial & drop caps

Those really huge single letters (or words) that appear at the start of the first paragraph are called drop caps and initial caps. Drop caps drop down into several lines of the paragraph. Initial caps sit on the baseline and rise upward well above the line.

Both are excellent ways to create a dynamic eye entry point for your lead. You can set their color and size (in points or numbers of characters deep/tall). You might even set the font to something that contrasts with your body font.

It's best to use only one drop cap per page or story and only at the very beginning. While it is possible to use more than one across a multiple-page spread, don't deploy them in every single paragraph. And if you do use more than one drop cap on a spread, make sure your drop caps don't accidentally spell out something offensive. You laugh, but it can happen.

Newspapers and other publications are dotted with examples of type used creatively. You'll commonly see logos, folios, pull quotes and other typographic design details giving life and order to otherwise dull pages.

Letterforms themselves can be interesting with angles and curves that contrast nicely with the rectangular shape of most screens and pages. Creative designers often manipulate the scale and orientation of fonts to turn type into visual focal points in lieu of photos, line art or other graphics. That's when things get really fun.

Icing On the Cake

Although most fonts have 265 characters, that's a far greater number than the sum of adding up upper – and lowercase letters, numbers and basic punctuation. So what's up with the other 100-plus characters?

Typesetter's punctuation

If you're still typing ellipses as “period space period space period space,” you're doing it wrong. Among those 265 characters are punctuation marks specifically drawn and spaced to match the rest of the glyphs in the font. If you know where to look, you'll also find a variety of specific punctuation glyphs you may not know exists, even though such glyphs are routinely necessary to produce professional-grade type.

For example, you need smart quotes (curly quotes) for quotations. You need the straight version of quote marks called prime marks for notating inches and feet without writing out the words “inches” and “feet.”

While you need the hyphen to create compound words, you need en dashes (historically the width of a lowercase n) for punctuating such things as the implied “to” in “3-4 weeks.” Then you'll need the slightly wider em dash—historically the width of a lower-case m—for dashes used to replace commas, colons and parentheses—when you're trying to be slightly more emphatic.

If you don't think the proper symbols look better than type kluges, we'll give you your money back. Okay, not really. But do check out what proper punctuation looks like and figure out how to use it. Because what you don't know about type can hurt you.

OpenType

OpenType fonts go well beyond the standard 265 characters. Designed to be functional across platforms to work on both Macs and PCs, these fonts may have as many as 65,000 characters. In addition to all the traditional punctuation marks and accent marks, OpenType fonts offer some or all of the following type options:

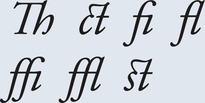

Ligatures

Ligatures are specially designed letter pairs—a single glyph meant to take the place of two traditional letters. Ligatures were created for certain letter pairs that join awkwardly because of the position of the dot of the “I” or hook of the “f,” for example.

Swash alternates

Old style figures

Ever notice that normal numbers often look too big and clunky when typed in with the normal flow of text? That's because the height of regular numerals is the same as uppercase letters. Regular numerals have the visual feel of all caps. An alternative is to use old style figures. Old style figures have varying x-heights, ascenders and descenders just like the rest of the letters in a font. Visually, they blend in much better with text.

Dingbats

If you've ever seen a decorative ornament to indicate that you've reached the end of the narrative, you've seen a dingbat. They look like little tiny pictures, but they really are font characters. Many fonts have a few as part of the 265-character set. Typically, OpenType fonts have more of them. Then there are fonts made up of nothing but dingbats.

Because they are technically font characters, you can style dingbats as you would fonts. You can change their size, color and orientation. They also can function as bullets, although, as always, use some discipline. Not all dingbats make good bullets.

Paired with letterforms, dingbats can be logos. Strings of them can become section breaks or borders. Or they can stand alone as artwork.

Still think type is boring? Neither do we. It is perhaps the most important tool in your visual communication toolbox. Use it. Don't abuse it.

Try This

1. Start a “swipe file” of neat typography and typesetting techniques. Look for anything with interesting type: logos; headline styles from magazines, newspapers and Web sites; sidebars and infographics; bulleted lists; opening slides from video clips; or interesting product packaging. Look for dingbats, ligatures, swash alternates and other uses of extended character sets, too.

2. Go to the candy aisle at your grocery store. Look for packages of the following types of candy: Gummy bears, traditional stick chewing gum, a milk chocolate bar, a chocolate bar with additional ingredients such as nuts or caramel and an expensive bar of dark chocolate. Look at the font choices on each package.

What categories of fonts does your candy-wrapper collection exhibit? Are the font choices appropriate for the target audience? Explain.

Design a candy wrapper for your own favorite candy. Write rationales for your choices.

3. Design a type-only logo for yourself. Use your logo to create your own set of custom business cards and letterhead. Or use your logo as the basis for a new resume design.

4. Create your one-color typographic self-portrait. Using only glyphs (including numerals and punctuation but not dingbats) create a closeup mug shot of yourself. Size contrast will be important. Direction, in the literal sense of turning glyphs topsy-turvy, also will be important. Otherwise, the rules go out the window since you're not using type to convey narrative information.

5. Research a famous font artist. Write a short history (a paragraph or two) and create a one-page layout using your history as the content. Use only fonts designed by your artist, and use only type in your design. No photos or illustrations allowed.

6. Create a vertically folding restaurant menu with a flat size at 8.5 inches wide by 11 inches high folded to a finished size of 4.25 inches by 11 inches. You'll need to design a cover and a two-page inside spread. A design for the back cover is optional. Begin with some menu copywriting.

Use typography to convey the kind of restaurant (casual Thai or upscale French, for instance). Create a visual hierarchy and a sense of isual order, too.

Demonstrate appropriate punctuation marks, paragraph indicators, bulleted lists and hanging indents, tabs and tab leaders, and whatever else is appropriate to your design.

|

what you need to know about logo design

Professional designers make logo design look easy. Some of the most powerful recognizable logos in the world are pictures of simplicity. The elegant appearance of these marks belies the fact that most logos require thousands of hours of brainstorming, sketching, rendering, rejecting and approving before they are launched. The stakes are high. One tiny little picture, or word and picture combination, must encompass the philosophy, activity, spirit and brand promise of an organization. This is why logo design is best left to professionals.

That said, you will have to work with logos in some form. Maybe you've hired a designer to create a logo for a new product launch. Or perhaps you need something simple for internal purposes, and you just don't have the budget to hire a designer. Whether you need to evaluate logos provided by a designer or you need to design something yourself, here are a few things you should know:

1. Logos should be unique to the subject/product/organization. Avoid anything too generic. If the design in question easily could represent another organization with the same name and a different mission, then go back to the drawing board.

2. Logos must be scalable. The design needs to be as clear and readable at the size of a postage stamp as it is at the size of an outdoor board. Avoid fine lines and details that disappear when a logo is reduced in size. If a logo uses more than one font, make sure both fonts are readable even when the logo is small.

The only scalable file format is vector so make sure you get vector versions of the finished logo. Vector filenames often end with the. eps extension. Photos are bitmap images and can't be scaled without loss of resolution. Never use a photo in a logo because photos lose resolution when scaled.

3. Simplicity is a virtue. What you want in a logo design is versatility. The highly complex illustrated logo may look great on the large sign outside, but what if you want to embroider the logo on polo shirts? Commercial embroidery companies will have a difficult time rendering your logo if it has too many details or fine elements, including serifs on fonts. If you must have a complex logo, make sure you have a simplified version as well.

4. Limit the number of colors. Simplicity also applies to the logo's color. The more colors a logo uses, the higher the printing costs. A good economical approach is to use two spot colors, often black plus another color. Spot colors are pre-established printing ink colors. Choosing a spot color is similar to choosing a paint color from swatches at a home improvement store. Because spot colors come “out of the can,” they are consistent. This is important if you're trying to build consistent visual branding.

5. Make sure the logo is reproducible in black only. Sometimes printing in color is not an option for budgetary or technical reasons. A logo must look clear and crisp printed anywhere. So it needs a black and white version. Black means black, too, not gray.

6. Make sure you can “reverse out” your logo. Reversing out is the design term for a logo appearing in white on colored or photographic backgrounds. Again, this is a flexibility issue. The logo needs to be clear and readable in all possible places it might appear. Hint: If the logo works in all black, it will reverse easily.

7. Be wary of designs that are too horizontal or too vertical. Such designs can be difficult to incorporate into layouts. If you're considering a design that is strongly horizontal, consider asking the designer to provide an alternate vertical version. This ensures that you have a good logo shape for any compositional situation.

If you must design a logo on your own:

First, purchase and learn to use a vector graphic program. Seriously. Logos need to be in vector format in order to be scalable.

If we still haven't convinced you to hire a logo designer:

1. Consider a type-only logo. Sometimes called a wordmark, type-only logos are perhaps a bit easier for beginning designers to manage. But only if you have the eye to classify and pair fonts. If you choose to use more than one font in your wordmark, make sure they contrast well but look good together. Think romance: “They make such an attractive couple.”

2. Avoid using the font-du-jour. We all have a few favorite fonts on our computers. A few fonts get done to death each decade. Some fonts were so over-used they've become synonymous with time periods. Some recent grossly overused fonts include Mistral, Papyrus, Copperplate Gothic and Zapfino.

A good rule of thumb is that if the font came installed on your computer, don't use it in a logo. Buy something new. Or down-load something new for free (but beware of copyright issues on free fonts). Or commission a font artist to create something new just for you.

3. No clip art. If you must add a graphic (often called an icon or symbol), consider a decorative dingbat or type ornament. But use care in your selection. A smiley face dingbat is no better than smiley face clip art.

4. Add a simple shape. If you're really feeling brave, consider adding a simple shape to your logo, such as a square, circle or rule. Pairing simple shapes with interesting glyphs can result in creative icons. For inspiration and guidance, revisit mini art school and the Gestalt Laws.

5. Test it out. Finally, as you consider and evaluate logos, be sure to see layout examples of the logo in use. Try the design on a Web page and a newsletter to see how the logo looks in context. You may find that what looks good standing alone on a presentation board doesn't hold up so well sitting atop a busy photo on your brochure cover.