Table 3.1 The Place of Intentions in Assessing Press Abuses according to Condorcet

To God, would I maintain that men might insolently spread satire and calumny against their superiors or their equals.

—Denis Diderot, “Libelles,” Encyclopédie, 1765

On December 27, 1788, Louis XVI’s Director General of Finances, Jacques Necker, announced the agenda for the upcoming meeting of the Estates-General. Among the many reforms to be discussed, Necker included press freedom, in these terms: “Your Majesty is impatient to receive the opinions of the Estates-General concerning the just measure of freedom that the press should be accorded for works or the publicity of works concerning public administration, government, or any topic of public concern.”1 Approved by the king, the report was printed up and distributed throughout France. With little more than four months to go before the meeting, the government was turning over the question of press freedom to the nation for reflection.

But the floodgates had already burst open. The monarchy’s attempt to abolish the parlements the previous May provoked a torrent of unauthorized pamphlets. On July 5, 1788, when Louis tried to resolve the crisis by agreeing to summon the Estates-General to discuss reforms, it was believed that he suspended censorship, and the outpour continued.2 But an explosion of print and temporary reprieve from censorship did not amount to legitimate freedom. As Necker saw it, the task ahead was to set new legal and regulatory parameters for the publishing industry.

Thinking through freedom and limits raised a number of questions. Why should the press be free? What risks did this freedom involve? And how should abuses be defined and limits enforced in order to secure benefits while avoiding drawbacks? In reflecting on these issues, revolutionaries drew from a wide range of Enlightenment ideas. This chapter examines this legacy. It begins by showing how conceptions of a self-regulating public emerged. Beleaguered by censorship and repression in the late 1750s, philosophes tried to outflank authorities by spreading the idea of a self-policing “public”—a public inherently immune to the influence of bad books and more effective than the state in punishing their authors. Later, once the philosophes had secured positions in the social, cultural, and political institutions of the Old Regime, they adopted less expansive notions of press freedom. They no longer maintained that public opinion was sufficiently capable of repressing abuses of this freedom. As calumny proliferated, contemporaries began meditating on the laws and regulations needed to deal with injurious print. In the final year of the Old Regime, the issue of press freedom became imbricated in political struggles among competing factions and institutions. Although nearly everyone agreed that the press should be free and that calumny should be punished, they disagreed on who should have the authority to define and enforce new laws governing free expression.

There may well have been a widespread desire for press freedom by 1789, but contemporaries were not naive about the power of publicity. They recognized that the outcome of their struggles depended greatly on the ability to control the policing of public opinion.

There was no coherent campaign for press freedom in the French Enlightenment. The story of an epochal struggle between freedom-seeking philosophes and a repressive state, depicted in many histories of the Enlightenment in the twentieth century, has recently given way to a more complex picture—one of complicities and compromises between writers, the Court, the royal administration, the parlements, and the Printers’ and Booksellers’ Guild.3 The philosophes did, to be sure, seek greater toleration for their ideas, if not for those of their adversaries. And although they sometimes criticized prepublication censorship and police repression, they rarely called for abolishing both at the same time.4 On the whole, they tended to be prudent and tactical in discussing press freedom, aware that courting, rather than castigating, authorities better served their interests, whether those interests involved the protection of their own works or the suppression of those of their enemies.

By midcentury, the philosophes had influential sympathizers at Court and in the royal administration.5 Support was provided licitly and illicitly. Licitly, the Directors of the Book Trade expanded the use of permissions tacites and permissions simples. Although these authorizations did not confer exclusive privileges and thus did not protect publishers from counterfeiting or prosecution for libel, books receiving them were usually, though not always, spared judicial repression.6 Illicitly, authorities sometimes abetted the underground market of unauthorized books.7 Even the Directors of the Book Trade and Lieutenants General of Police (the positions overlapped after 1763) occasionally conspired to circumvent their own system of licensing and surveillance, sending manuscripts abroad to be printed and protecting them when they came back as books into France.8

Yet, complicity between the philosophes and authorities should not be overstated. Directors of the Book Trade and Lieutenants General of Police were subject to pressure from many sides, and their efforts to help the philosophes sometimes encountered formidable resistance. Enemies of the Enlightenment at Court, in the Church, and in the parlements tried to drive the philosophes out of existence.9 Although they did not succeed, their efforts led to not a few condemnations, book seizures, and lettres de cachet. Individuals involved in the book trade, including authors, found themselves thrown into the Bastille and other such prisons with increasing frequency in the decades between 1750 and 1780.10 Thus, even as the Enlightenment gained increasing legitimacy in society, the personal and financial risks of writing and publishing remained high.11

The vicissitudes of official tolerance for the philosophes helps explain their ambivalent, tactical pronouncements about press freedom. With the sympathetic Malesherbes at the helm of the Book Trade and authorization to publish the Encyclopédie in the late 1740s and early 1750s, they had little reason to complain. The situation changed abruptly in the wake of the Damien Affair of 1757. In the aftermath of the assassination attempt on Louis XV, the Conseil d’État declared all writings attacking religion or the state to be punishable by death. Two years later, the Parlement of Paris condemned the Encyclopédie, and the project went underground.12 The magistrates also condemned Helvétius’s materialist and sacrilegious De l’Esprit, burning it on the steps of the Palais de justice, thereby humiliating the royal censors for having approved it.13 Five years later, the Parlement passed a Law of Silence prohibiting public discussion of administration and royal finances.

It was in this “dark period,” as Robert Darnton calls it, that the philosophes honed their most radical ideas on press freedom.14 They employed two arguments. First, they denied that books could provoke sedition. In his 1764 Dictionnaire philosophique, Voltaire quipped, “I know of many books that bore; I know of none that have caused real harm.”15 A year later, he seems to have taken a page from Hume’s 1742 “Of the Liberty of the Press,” expounding on the peaceful progress that comes only through reading.

Each citizen can speak to the nation through writing, and each reader can examine leisurely and dispassionately what his compatriot submits to him through the press. Our assemblies can sometimes be tumultuous: it is only in the contemplation of the reading room that one can do good.16

The article “presse” in the clandestinely published volume of the Encyclopédie repeated this view, asserting that readers were “immune from contracting passions.”17 In his 1764 Refléxions sur les avantages de la liberté d’écrire et d’imprimer sur les matières de l’administration (it was not published until 1775), André Morellet wryly dismissed Parlement’s concerns that a free press would stir up the people: “It is strange that one opposes the advantages [of press freedom] with such vague fears.”18 According to Morellet, if troubles occurred in the wake of a publication, it was the fault of authorities, not writers and publishers. “It is false that public tranquility can be disturbed [by writings] in any state where authorities know how to attain respect”—that is, where authorities know how to govern respectably since the public, Morellet assumed, was reasonable and of one mind in its judgments.19

Another argument for press freedom advanced during this “dark period” held that public opinion was inherently self-regulating and that, consequently, it was useless, even counterproductive, for authorities to obstruct the circulation of ideas. Borrowing freely from Montesquieu’s De l’esprit des lois, the authors of the article “libelles” in the Encyclopédie claimed that libels and satire were unknown in the East where despotism hampered the intelligence and wit needed to write them—a roundabout way of flattering the French for indulging in the vice. In a thinly veiled dig at authorities, they argued that in aristocracies, libels were punished severely because magistrates were “as little sovereigns not strong enough to dismiss insults.” And while democracies tolerated libels, which served as a check on authority, “enlightened monarchies” treated them as mere misdemeanors, punishing them through mild “correctional policing.”20 The encyclopédistes departed from Montesquieu’s views, however, in positing the notion of a self-regulating “public opinion,” one that was sufficiently capable of punishing scandalous writers. Glossing over how the public did so, they, like Morellet, blamed authorities for disturbances, believing that as long as sovereign authorities did nothing reproachable, they need not worry about the impact of libels. “Decent people embrace the party of virtue and punish calumny with contempt.”21

These were provocative assertions, but the encyclopédistes (or their meddlesome editor) tempered them with conventional appeals to the law. It is worth citing their argument in full, for it appears neither in De l’esprit des lois, which inspired most of the article, nor in Diderot’s more radical (but unpublished) tract Lettre sur le commerce des livres of 1763.

To God, would I maintain that men might insolently spread satire and calumny against their superiors or their equals. [Apparently, social inferiors were fair game.] Religion, morality, the right of truth, the necessity of subordination, order, peace, and tranquility of society all conjoin to detest such audacity; but in a [well-regulated] state, I would not want to repress such licentiousness through means which would destroy all freedom. One can punish abuses through wise laws, which in their prudent execution unite justice with the greatest happiness of the people and the preservation of the government.22

The concession lent an air of conventionality to what was otherwise a radical stance. Still, the article said nothing about what “wise laws” were to consist in.

The next article appearing in the volume, “libelles diffamatoires,” was unequivocally conventional. While readers of the previous article may have relished the idea that authorities should be held accountable to them (the public), they would have been comforted to know that their own reputations would not be brought before this court. The authors summarized the Old Regime jurisprudence on injurious speech, stressing its hierarchical aspects. They observed that punishments were set according to the status of the person attacked and the conditions under which the libel was produced. If the defamation involved calumny, “the author is punished and sometimes sentenced to death.” Executions for calumny were rare in the eighteenth century, but not unheard of.23 In any case, the fact that the article conveyed no criticism about such conventions suggests that the encyclopédistes, or their squeamish editor who often mutilated their articles, accepted the status quo or felt that readers needed to be assured that they did.24

Diderot’s 1763 Lettre sur le commerce de la librairie, which was not published until 1861, advanced what was arguably the most radical position on press freedom during the French Enlightenment. The Printers’ and Booksellers’ Guild had hired Diderot to propose new regulations to the new Royal Administrator of the Book Trade and Lieutenant General of Police, Antoine de Sartine, but his tract turned out to be too radical for the guild, which gave it a thorough overhaul and a new title before submitting it.25 Most studies of the tract situate it within complex struggles over privileges and literary property, and indeed, those issues are central in the text.26 But Diderot also advanced quasi-libertarian views about how press abuses should be handled. In calling for permissions tacites à l’infinie—permission for all publications regardless of content—he stressed the futility of both prepublication censorship and postpublication repression. He assured that a truly bad book—one so dangerous that no author or printer would dare submit it to the censors, even for a permission tacite—would meet with the public’s wrath. He made no mention of the “wise punitive laws” alluded to in the Encyclopédie. Apparently, there was no need for them. For should a truly dangerous book appear, the public would be so outraged, it would express its choler in the form of “public vengeance.”27 “Public vengeance” is certainly more severe than “public contempt,” the term used in the Encyclopédie, and it might be considered nothing more than rhetorical excess. But if there was an exaggerated concept at play in Diderot’s argument, it was not “public vengeance.” Rather, it was the notion of a reasonable public—a uniform body of opinion capable of discerning truth from calumny and of punishing the latter. As we have seen, the public sphere in eighteenth-century France defied the sanitized portraits the philosophes made of it. When stakes were high, dispassionate reason often gave way to vindictive libel, and the public sphere became a battlefield for struggles over honor and esteem—the prerequisites for power.

The philosophes were well aware of this. When Voltaire wrote scandalous tracts in the name of Rousseau to compromise the “citizen of Geneva” in the Republic of Letters, he counted on the public’s inability to discern truth from dissimulation.28 Diderot’s and d’Alembert’s lack of confidence in public opinion prompted them to go running to the Lieutenant General of Police when a libel cut too close to the bone. In 1772 the abbé Antoine Sabatier, a former philosophe, published a scathing indictment of the encyclopédistes in Trois siècles de notre littérature. Diderot and d’Alembert begged Sartine to suppress the work. Sartine asked them if it impugned their mœurs or private conduct. They insisted that it did, since it predicted the greatest calamities as a result of their principles. Sartine rejected their argument. Turning their own principles back on them, he told them to take their complaint to the public.29

Clearly, there were limits to how far the encylopédistes would go in erecting public opinion as the supreme tribunal over the printed word. Still, the notion of public opinion as such persisted, taking on a life of its own in the course of political struggles during the Old Regime’s final decades. As Keith Baker has shown, magistrates—notably Malesherbes, who, after resigning as Director of the Book Trade in 1763, devoted himself to judicial functions in the Cour des aides—viewed it as a legitimate restraint on sovereign power once the parlements were abolished in the Maupeou coup of 1771.30 So, too, did Jacques Necker after he was dismissed as Director General of Finances in 1781.31 Both men, we shall see, would temper this view on the eve of the Revolution. If the “tribunal of public opinion” was a powerful notion, it was essentially an oppositional one—readily abandoned when the alienated or ousted managed to secure (or resecure) power.

By the 1770s, the philosophes’ situation had changed. They were working their way into the establishment, holding influential posts in the administration and cultural institutions.32 From such elevated positions, the problem of press freedom and limits looked different. Erecting public opinion as the final word on taste, morality, and politics seemed less important than establishing legal, institutional, and moral parameters for the world of print. And given the cultural and political battles raging in the 1770s and 1780s, there were compelling reasons to be thinking about such parameters. In the wake of the grain crisis of 1768, Ferdinando Galiani, a Neapolitan diplomat and man of letters in Paris, wrote a controversial tract attacking the philosophical foundations of physiocracy. The tract, Dialogues sur le commerce des bleds, also criticized the philosophes’ mode of disputation in promoting the new economic policy, sending shock waves through the Republic of Letters. In the bitter pamphlet war that ensued, aggrieved parties sought the support of Sartine, then Director of the Book Trade and Lieutenant General of Police.33 The Republic of Letters was further divided by the Maupeou coup of 1771. While Voltaire supported the radical judicial reforms, other philosophes defended the parlementary magistrates, their erstwhile repressors.34 Finally, contested appointments to the Académie française and the Académie des sciences where the encyclopédistes were gaining strength had the effect of pitting members against each other and stirring up debate over the need to censor the Academies’ own (calumnious) publications.35

Marie-Jean-Antoine-Nicolas Caritat, the marquis de Condorcet was in the thick of these struggles. His appointment as assistant secretary to the Académie des sciences in 1773 was a highly contentious affair.36 He became an advisor to Anne-Robert-Jacques Turgot, Controller General of Finances between 1774 and 1776. An enthusiastic supporter of press freedom himself, Turgot appointed Condorcet inspecteur des Monnaies in 1775, around the time when his liberal economic reforms were stirring up violence and published protest.37 It was in this context that Condorcet wrote his Fragments sur la liberté de la presse. The text marks the most thorough contemplation of the “wise laws” that were to accompany the abolition of prepublication censorship. Condorcet’s ideas on press freedom are worth investigating, not because they served as a blueprint for revolutionaries but because they shed light on the tensions surrounding the issue in late eighteenth-century France. They give insight into the tolerance thresholds that Condorcet assumed his readers shared.

According to Condorcet, the most serious print crime was sedition. Absolutists would have agreed, of course, but Condorcet erected a mountain of criteria for determining guilt. First, proof had to be furnished that the accused not only wrote the work in question but also engaged in having it circulated.38 Second, it had to be demonstrated that the work in question contributed to a wrongdoing and that this wrongdoing resulted necessarily from the publication. Finally, it had to be demonstrated that the author intended this wrongdoing.39 Clearly, Condorcet’s plan would have made indictments for sedition next to impossible to obtain. Yet, he included a backdoor clause. In periods of unrest, such as war or civil strife, press freedom could be suspended. He gave historical examples of times when authorities proscribed, rightly in his view, certain forms of expression. “It was in this way,” he wrote,

that Queen Elizabeth could, without tyranny, ban for a time unauthorized preaching. . . . The act of preaching is itself irrelevant. Every man has the right to preach to those who want to listen to him; every man has the right to be preached to by whomever he wants. But since this freedom can stir up unrest, Elizabeth had the right to justifiably suspend this law for a fixed period of time.40

Condorcet thus built a “state of exception” into his plan; press freedom could be sacrificed for the sake of preserving the general order.

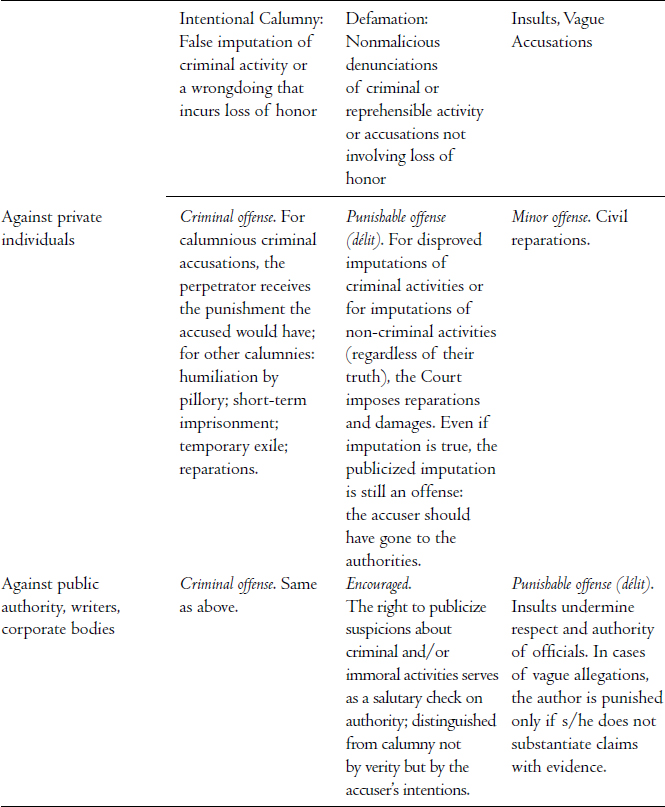

For Condorcet, speech offenses against public figures (officials, guild leaders, and authors all shared “public” status in his plan) were to be treated differently from those against private individuals (particuliers). He identified three kinds of speech violations: calumny, defamation, and insults or vague accusations (see table 3.1). The worst was calumny, which referred to the malicious and false imputation of a criminal or dishonorable action to someone. The perpetrators of calumny against public and private figures were to undergo the same punishment that the victim would have undergone had the denunciation been determined to be true. Matters became more complicated in cases of defamation and insult. Defamation was defined as the nonmalicious (in intent) public accusation of criminal or reprehensible activity. According to Condorcet, defamation against a private individual was to be treated as a serious offense, even if the accusation turned out to be true, since the denunciator should have submitted the matter to authorities.41 Inversely, defamation against public figures was to be tolerated and even encouraged. Indeed, the very purpose of press freedom was to empower the public to censure and monitor authorities. If writers had to worry about reprisal for voicing suspicions or for hazarding accusations that, after further investigation, turned out to be false, the chilling effect would hamper public opinion’s function as a check on authority.42

These guidelines posed a potential problem: how were the courts supposed to distinguish between punishable calumny and virtuous defamation if “truth” was irrelevant? The jurists Dareau and Jousse, we have seen, emphasized the importance of determining the relative social status of the parties involved. For Condorcet, however, culpability depended upon the author’s intentions. His position on this point is worth highlighting; for I believe it helps explain judicial practices during the Terror. In the highly polarized climate of revolution when truth was too difficult (or contentious) to ascertain and social status no longer mattered, tribunals sought to uncover the moral and political consciences of suspects. “What were your true sentiments on August 10, 1792, when the monarchy fell?”43

Condorcet also proposed employing different criteria in assessing insults, or vague accusations, against public and private figures. Whereas such speech was to be treated as a minor offense when it concerned private individuals, it was to be treated as a serious crime when directed at public figures. This reasoning differs from the views of Montesquieu and the encyclopédistes, who believed that the attribution of lèse-majesté should not pertain to such speech. In De l’esprit des lois, Montesquieu stated, “Nothing renders the crime of high treason more arbitrary than declaring people guilty of it for indiscreet speech.”44 Disrespectful criticism, the Bordeaux magistrate argued, could even be salutary, especially in monarchies where it served as a kind of collective psychological release valve. “[It] consoles the disgruntled, diminishes jealousies, gives the people the patience to suffer, and makes them laugh at their own sufferings.”45 The harshest treatment that satire or libels merited in a monarchy, according to Montesquieu, was correctional policing, which, in the Old Regime, tended to involve relatively modest fines or short stays in prison.46 Condorcet, on the other hand, stressed the political dangers of disrespect. “Each citizen has the right to judge the conduct of the employees of the nation; but no one has the right to take away public esteem [from a public official] through vague imputations.”47 As for insults, he believed they were even more dangerous than calumny. Since calumny imputed a concrete crime, it could be disproved. Insults, however, deprived officials of the respect the community invested in them, respect that was needed to exercise authority and maintain the community’s well-being.

Condorcet’s legal framework for press freedom thus narrowed the range of permissible speech. Of the three kinds of injurious speech—calumny, defamation, and insult—only defamation, that is, an accusation made in good faith of criminal or reprehensible actions, was to be tolerated and only in cases in which public figures were the targets. But distinguishing the permissible from the punishable—civic denunciations from calumny—required assessing authorial intentions. Condorcet offered no guidelines for how to do so.

Condorcet’s proposal also narrowed the role of public opinion. Whereas earlier philosophes depicted public opinion as sufficiently discerning and self-regulating to pass judgment on all public matters, Condorcet believed that this “tribunal” should have limited jurisdiction. It was to be the final court of appeals only for affairs concerning violations of mœurs, such as pornography.48 He insisted that it was as ignoble for the state to punish such offenses as it was for someone to engage in them. Circumscribing public opinion still further, he distinguished between public opinion and publicized opinions, holding that the public’s censure of mœurs violations should be restricted to casual conversation and banned from print, copied manuscripts, and songs. While he recognized the salutary influence of an opprobrious “public opinion” on mœurs, he emphasized that the publicity of its judgments could be disruptive.

Thus, in Condorcet’s schema, public opinion figured as an abstract repository of censorious sentiments. But he wanted it to remain abstract, depriving it of the means to compete with state institutions. He reiterated this argument again in 1789, a time when notions about public opinion were becoming mixed up with discussions about more democratic forms of sovereignty. In an open letter to deputies to the Estates-General, he wrote, “Public opinion exerts over us a nearly irresistible force; it is a useful instrument, but one to which no external force should be added, in giving its decisions a solemnity which would allow no possibility to resist it.”49 He discouraged the idea, which must have been circulating at the time, that public approbation and disapprobation of deputies’ actions should be institutionalized as a form of civil censorship. In the spirit of his 1776 tract, he feared that giving censorious expression an institutional base would undermine law and authority, leading to divisiveness and anarchy. Deputies would become the slavish agents of local factions and be inhibited from exercising authority through their individual conscience and reason. He concluded, “A virtuous man can withstand a dispersed public opinion; but the strength to withstand it once it is consolidated . . . into a respected organ is almost beyond human capabilities.”50

Condorcet’s insistence on the law as the ultimate regulator of speech presupposed a neutral, disinterested application of it. Judicial neutrality, however, was too much to expect in the final decades of the Old Regime, when the judicial order itself was at the center of political struggles. It is quite possible that Condorcet drafted Fragments sometime between 1771 and 1774, when the parlements had been abolished and enlightened administrators were trying to establish a new legal-judicial system. In the late 1780s, when the monarchy again tried, but failed, to dispense with the parlements, the magistrates would resist, provoking a political crisis that brought the Old Regime to a grinding halt. In the new regime of press freedom that opened up, legislative and judicial institutions could not be counted on to be sufficiently impartial in defining and enforcing press laws.

Tracts on press freedom proliferated in the months before the meeting of the Estates-General, and even royal officials got in on the act. Those by a former censor, Malesherbes, and a current one, Dieudonné Thiébault, are exceptional in their length and depth of reflection. After stepping down as Director of the Book Trade in 1763, Malesherbes worked on and off for the government and magistracy and had just resigned from his position as Royal Minister in the summer of 1788 when the government asked him to submit his ideas on press freedom. Although he repeated many of the suggestions he had made in his 1758 Mémoires sur la librairie, he now took into account the new political landscape, notably, the political position of the parlements and the imminent abolition of mandatory censorship. Thiébault’s tract, which bore the same title as Malesherbes’s manuscript, considered these issues even more rigorously. Unlike Malesherbes’s memoir, Thiébault’s Mémoire sur la liberté de la presse was published. It figured in debates on press freedom in 1789.

Historians have tended to see Malesherbes’s and Thiébault’s texts in different lights. While views on Malesherbes vary (he is seen as either a champion of liberalism within an oppressive regime or a moderate conservative), there has been more consensus that Thiébault was an outmoded defender of the Old Regime and that his tract was little more than a half-hearted, roundabout call for maintaining censorship.51 Yet, these two men conveyed similar views, and they were quite innovative and astute in their reflections. Even if neither called for the outright abolition of censorship, they drew upon Enlightenment ideas in proposing ways to extend freedom to writers while protecting them from arbitrary, postpublication repression. Both authors envisaged protecting writers and empowering public opinion by establishing a system of checks and balances between the administration and the courts.

Malesherbes knew much about the difficulties in trying to establish such a system. Dismissed in 1771 from his post as first president of the cour des Aides in the Maupeou coup, he wrote remonstrances over the next several years in which he insisted on the benefits of press freedom as a check on absolute monarchy.52 In 1787, he accepted a position as Royal Minister, though not without hesitation. A year of working for the monarchy was enough to have cultivated in him a distrust of the parlements. Whereas he had defended the magistracy against royal “despotism” in the early 1770s, on the eve of the Revolution he presented royal censorship as a salutary check on the despotism of the parlements.53

Malesherbes’s background helps explain what appears to be a curious contradiction in his Mémoire sur la liberté de la presse: he called for both press freedom and censorship. The censorship he envisaged differed from the one practiced until then. He proposed that authors choose to either submit their works to the censors with the guarantee that, if approved, they would receive judicial immunity, or bypass the censors at their own “risk, peril, and fortune.”54 For Malesherbes, there was no doubt that writers and printers should be held accountable for abuses of press freedom, such as calumny, breaches of bonnes mœurs, and attacks on religion and sovereign authority. But it was the unchecked authority of the parlements that Malesherbes regarded as the greatest threat to press freedom.

In a letter to the Controller General of Finances, Étienne-Charles de Loménie de Brienne, in 1788, Malesherbes observed that the parlements now had a monopoly on speaking for the nation.55 He wrote this when it appeared that the public was encouraging the Parlement of Paris to challenge the crown’s attempt to abolish the parlements.56 But by winter 1789, when Malesherbes completed his manuscript, the situation had changed. The public was now suspicious about the Parlement’s stated commitment to equitable reforms, and he feared that if the magistrates continued exercising exclusive punitive authority over the world of print, they would soon become despotic. While conceding that royal censors could sometimes be tyrannical, he held up royal censorship as the lesser of two evils.

The principles of censorship are arbitrary [according to Enlightenment writers] . . . but if books are deemed reprehensible by the judicial system, it will no longer be the whims of a single man on which [the fate of] a book will depend; rather, it will depend on [the whims] of all the councilors of the Parlement and Châtelet, who, if displeased with a book, will find it appropriate to denounce it.57

Malesherbes based his misgivings about the French magistracy on several factors. First, unlike their English counterparts, French judges formed a self-interested corporation and conducted certain proceedings secretly.58 Second, French magistrates did not have the expertise to adjudicate affairs concerning complex subjects, such as theology and metaphysics. Judges were often moved by the eloquence of plaintiffs seeking to protect their intellectual fiefdoms.59

In a footnote, Malesherbes deviated from his general reflections to slip in his suspicions about the Parlement’s recent arrêté in favor of press freedom. He warned,

Nothing better reveals the arbitrariness of the rules . . . that the Parlement proposes to follow as soon as it obtains what it calls “the freedom of the press” than the terms of its recent arrêté which, in calling for this freedom, excepts “reprehensible works, whose authors will be held to account.”60

He added that if seventeenth-century writers like Molière and La Bruyère had lived under such a free-press regime, they would have spent most of their time in court.61 The arrêté that Malesherbes was referring to had been issued on December 5, 1788. In many ways it prefigured Article 11 of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen. The Parlement called for

the lawful [légitime] implementation of the freedom of the press, the only prompt and sure means for good people [to combat] the licentiousness of the wicked, excepting reprehensible writings for which authors are answerable according to the law.62

“Lawful” implied legal limits, a qualification that amounted to asserting the Parlement’s exclusive authority to determine and punish press abuses. Malesherbes’s suspicions were not unfounded. In an earlier passage of the arrêté, the Parlement signaled its intention to punish its opponents, referring to

the maneuvers practiced in the realm by ill-intentioned people to deprive the nation of the fruit of its magistracy’s efforts by substituting the fire of sedition and the horrors of anarchy for the desirable success of a generous and wise freedom.63

In a single strike, the Parlement of Paris presented itself as the stalwart defender of press freedom, arrogated to itself the authority to define and pursue abuses, and warned its opponents that it regarded them as seditious.

It is in this political context that Thiébault’s Mémoire sur la liberté de la presse should be reappraised. This ex-Jesuit has been depicted as sailing against the prevailing currents, the sole conservative defender of a system under inexorable collapse. Many of his proposals and commitments, however, did not differ from those of Malesherbes. Both suggested reforms that would extend more freedom to authors while avoiding the drawbacks that they thought unlimited press freedom might engender. For Thiébault and Malesherbes, press freedom meant freedom from the tyranny of the parlements and from mandatory royal censorship. However, the best way to avoid the former, they believed, was to submit voluntarily to the latter.64

Like Diderot and Malesherbes, Thiébault believed it was impossible to stop the circulation of bad books. “Abuse is inseparable from the common use of things, as long as there remains an ounce of freedom.”65 He reasoned that just because guns could be used to kill people, governments should not start banning them.66 Still, abuses were to be punished, and Thiébault proposed that if writers declined to submit their works to the censors, they, along with the printer and distributors, could be held legally accountable for offenses in print. If, however, submitted works were approved, they were to be immune from all prosecution, except in cases of calumny and defamation.67 (He thought that since slander could be subtle and go undetected by the censors, authors should always be held responsible for such offenses.)68 Thiébault added that a writer whose work was submitted but refused an approbation should also be immune from prosecution, unless, of course, the author chose to have it published and circulated anyway. This immunity was justified because the author had demonstrated good faith in submitting the work in the first place.69

FIGURE 3.1. Dieudonné Thiébault. Courtesy of the Carnavalet Museum.

Thiébault shared Malesherbes’s distrust of the parlements. He argued that, without the protection of the censors’ approbation, authors would become vulnerable to the whims of the magistrates. Whereas under the old system, printers and distributors were held responsible for bad books more often than were authors, under a free-press regime, more would be printed, but “the number of guilty authors will necessarily increase.”70 If the courts’ arbitrariness could not be avoided (and he doubted that it could), the magistrates would end up exercising “the most encompassing, absolute, and formidable influence over public opinions, the doctrines of the Nation, and people’s minds.”71 Alluding to the monarchy’s current struggle against the parlements, he pointed out a contradiction on the part of those who demanded unlimited press freedom while decrying the tyranny of the parlements.

You fear aristocracy, yet you are about to establish the most complete aristocracy in the name of freedom! You say that your magistrates have exercised too much influence over your laws, yet you are going to give them authority over the very ideas upon which the laws themselves are to be based. You complain about speech restrictions, yet you are [now] going to open yourselves up to the most severe inquisitions! You do not want to be held back any longer from doing wrong, yet you yourselves are about to authorize a law which will inevitably strike at your property, happiness, freedom, and life.72

Thus, Thiébault and Malesherbes thought in terms of checks and balances. Voluntary censorship run by the royal administration, they believed, would serve as a check on parlementary tyranny. Furthermore, since neither the administration nor the parlements would exert exclusive control, the press would become more responsive to demands from below. The victims of oppression would feel freer to air grievances, knowing that complaints against the monarchy would not be pursued by the parlements and that complaints against the parlements would be protected by the legally binding approbation of royal censors.73

Still, the right to denounce through print did not, according to Thiébault, exempt authors from responsibility for calumny. Like most enlightened contemporaries, he thought that press abuses were punishable. For Thiébault and Malesherbes, abuses were those already defined by Old Regime law: attacks against mœurs, government, religion, and the honor of citizens. In discussing these matters, Malesherbes exuded more tolerance, though less rigor, than did Thiébault. He dismissed concerns about threats to the “principles of government,” pointing to the fact that the king had already suspended censorship requirements for tracts dealing with reforms. As for religion, he believed that controversies over Jansenism, so tumultuous in the past, were now over. In his view, therefore, “fears about the threat of press freedom for religion and government have often been exaggerated.”74 For Malesherbes, “the censor should watch over all that concerns public order and do no more than that.”75

Whereas Malesherbes had little to say about attacks on religion, except that they might provoke trouble and should be repressed if necessary, Thiébault expounded on their danger.76 He viewed them in much the same way as Montesquieu and Rousseau had viewed attacks on mœurs: the sign of society on the brink of self-destruction.

And who could ignore the terrible havoc that metaphysical sophisms have wreaked among weak minds! We cannot deny that among all Peoples, in all centuries, and under all systems [of government], men’s respect for religion has never been altered without public corruption ensuing quickly thereafter along with the dissolution of social bonds!77

According to Thiébault, an entirely unrestricted press would not only destroy mœurs and honor; it would also undermine the state’s (unwritten) constitution and legitimate authority.78

Clearly, Thiébault was no radical. And it might even seem that he was insincere about the freedom he was proposing. Whereas other proponents of press freedom trumpeted its virtues while ignoring the question of limits, Thiébault assumed that limits were necessary and stressed the importance of cultivating the sentiment of freedom, that is, the notion one has about the will she or he exerts.

It is the sentiment of freedom and not freedom itself which raises us up and ennobles us. . . . He who were a slave without knowing it would still be capable of virtue. . . . It is better, from the political point of view, to give the Nation the true sentiment of press freedom rather than the real thing in its unlimited form.79

Although Malesherbes and Thiébault agreed on much, they differed on some points. Malesherbes condoned anonymous writings, seeing them as necessary for society to confront despotism without risk of reprisal. He mentioned Montesquieu’s aversion to anonymous denunciations but dismissed it.80 Thiébault, however, thought that the names of authors and publishers should appear on all publications. In the case of works approved by the censors, the name of the author would already be registered. But what about works not submitted voluntarily to the censors? Thiébault suggested that a copy of all publications, approved or not, be submitted to a public depository, each page signed by the author and printer along with a declaration of responsibility for the content. This formality, he argued, would protect authors from subsequent changes that printers might make—a chronic nuisance of eighteenth-century literary life—and ensure legal accountability.81 In addition, Thiébault believed that writers should furnish a cautionary sum to ensure that, in the case of libel, injured parties would be compensated.82 Thiébault’s readers may have wondered how “the weak,” whom his free-press regime was supposed to empower, might afford this. In any case, such concerns are entirely absent from Malesherbes’s tract.

Unlike Malesherbes, Thiébault recommended maintaining censorship of newspapers and almanacs. Newspaper licensing, he insisted, was to be obligatory and the number of licenses limited. Why? He followed a tortuous path in arriving at this conclusion. At first, he considered putting newspapers under the same kind of voluntary censorship as books. But he believed that the celerity with which newspapers circulated and the immediacy of their widespread impact rendered them more bound up with the public interest than books.83 (It should be noted that such rationales inspired regulations on radio and television in the twentieth century.) Thiébault was also concerned about the financial interests of subscribers who might lose substantial sums should a newspaper operating without a privilège be shut down.84 As for almanacs, Thiébault considered their information too important to leave to the open market. He believed that errors could have grave consequences for an agricultural society highly dependent on this information.85

Malesherbes did not treat the issue of newspapers. In fact, he ignored or glossed over many of the implications of press freedom that Thiébault took seriously. The most significant problem Malesherbes overlooked was how press offenses against the public were to be handled, particularly threats to public order, religion, bonnes mœurs, or principles of government. While he recognized that such abuses could exist and should be dealt with, he offered no criteria for assessing them and no guidelines for bringing “bad” authors and printers to justice. Malesherbes’s tolerant, liberal tone was achieved by simply skirting thorny issues.

Thiébault gave abuses of press freedom deliberate consideration. He proposed establishing a bureau of censors, not at all related to the censors who issued approbations for books. These censors would form an academy independent of the government. They would comb newspapers for announcements of new books not approved by the royal censors. Embodying public opinion, the censors would read these books, informing the administration about dangerous ones so that advertisements could be suppressed.86 At this stage, the work could still be circulated. If the censors determined that the work in question was extremely dangerous, the Public Minister would intervene. The Minister could stop the circulation of an allegedly dangerous book only for a short time and would have to bring the affair before a court. If the court did not adjudicate within a specified period, the book would be permitted to circulate.87

With what criteria were the Public Minister and the courts supposed to assess a denounced book? And if it were determined to be seditious or calumnious, what punishment was to be be imposed? After raising these questions, Thiébault modestly admitted that he did not have answers. For calumny against individuals, he saw little difficulty in calculating punishment; like Condorcet, he thought that it should be in proportion to the risks and/or suffering to which the victim had been exposed.88 But for crimes against society, the risks and injury were difficult to measure. Like Condorcet, Thiébault believed that the degree to which a bad book was criminal depended, at least in part, on the circumstances in which it appeared.89 He urged enlightened citizens to give these matters further reflection in order “to give us the penalty which we lack and which alone can thwart arbitrary judgments.”90

Of all his concerns, Thiébault worried most about the unchecked power of the parlements. Like Malesherbes, he feared that repression would be far more arbitrary if left solely to the discretion of the sovereign courts, which held both legislative and judicial powers. Voluntary censorship run by the royal administration, he believed, would serve as a check on the parlements. Summing up the options to his readers, Thiébault asked, “Do you prefer the power that prevents wrongdoing or the power that punishes it?”91

At least one revolutionary journalist responding to Thiébault’s tract insisted that he preferred punishment. Gabriel Feydel, editor of the newspaper L’Observateur, scoffed at Thiébault’s arguments. In an issue appearing in August 1789, Feydel wrote, “Don’t ever forget that the law must act through punishments, and not through prohibitions.”92 A week later, he criticized Thiébault’s tract. “In vain M. Thiébault objects that the freedom of the press might have drawbacks.”93 He continued, “We respond to M. Thiébault that prohibition is the arm of despotism, punishment the arm of the law.”94

Feydel was not alone in extolling the virtues of a legal, ex post facto punitive regime over a regulatory one. In a pamphlet appearing in June 1789 shortly before the third estate declared itself to be the National Assembly, Jacques-Pierre Brissot de Warville demanded the abrogation of all Book Trade regulations. Still fuming over the arrêt du Conseil of May 6–7, which shut down his newspaper, Brissot urged the Estates-General to declare press freedom, pass new press laws, and establish a new court to try censors for having violated this freedom. He conceded that press abuses needed to be dealt with but insisted that preventative censorship had no legitimate role. “It is necessary to prevent licentiousness, libels, etc. . . . [This is] a valid principle, for which the application of censorship is wrong. . . . Without doubt, it is necessary to prevent offenses, but [this should be done] through laws and not through arbitrary regulations.”95

What laws? Brissot was vague on this point, admitting that “it is difficult to reconcile [press] freedom with the desire to punish calumniators.”96 Indeed, a press regime based entirely on law raised several complicated issues: “To what degree should the public have the right to censure its representatives and executive power? When does censure amount to libel? These questions pose great difficulties, and I dare to say that they have not been sufficiently discussed in any Constitution, not even in England.”97 Brissot encouraged the Estates-General to take time to reflect carefully before passing the appropriate legislation. In the meantime, he proposed a temporary, working definition. To “outrage” or “calumniate” a member of the Estates-General, according to Brissot, involved attributing to that member speech, opinions, or actions that would “dishonor” him before the Assembly.98 Thus, just as during the Old Regime, honor and hierarchy mattered more than truth.

Brissot urged deputies to pass a temporary law authorizing the Estates-General to censure and imprison those found guilty of libel against deputies, “for to insult [them] is to insult the Nation itself.”99 If a deputy were to write such a libel, he was to be expelled from the Estates-General. Given Brissot’s enthusiasm for Anglo-American constitutionalism with its separation of legislative and judicial powers, explaining how legislators could justly adjudicate affairs of honor involving themselves required creative argumentation. He conceded that the Estates-General could not preside over all criminal affairs without falling into despotism.100 However, allowing them to adjudicate affairs involving political libel would give them absolute authority over just one small part of the law. And in any case, as he assured his readers, such cases were rare in the United States and Britain.101 To this rather weak argument, he added that the Estates-General’s jurisdiction over such affairs was justified because of their supremacy over all other institutions. He warned that if rival institutions had this jurisdiction, they would try to undermine the Estates-General by letting libellistes off the hook.102

Brissot’s proposal was clearly designed to advance the cause of the Estates-General, which, at the time of publication, was being dominated by the third estate. Abolishing censorship would loosen the monarchy’s already tenuous grip on publicity; giving the Estates-General exclusive jurisdiction over political libels would neutralize the parlements; and with provisional laws maintained at the discretion of the Estates-General (soon to become the National Assembly), why hurry to define speech offenses? As it turned out, legal limits would not be defined until summer 1791.

Ultimately, then, all political camps but the Church had reasons for demanding press freedom in 1789. (And as we shall see, even much of the clergy supported it.) Yet, all camps also had reasons to keep the authority to enforce limits within their own sphere of control. Indeed, the stakes were too great and the influence of publicity too strong to leave the setting and enforcing of limits to adversaries. In the short term, it appears that Brissot’s views prevailed. The National Assembly successfully navigated between the Scylla of censorship and the Charybdis of the courts, emerging as the sole legitimate authority to determine limits on press freedom, even if it did not get around to defining them for two years. Meanwhile, old and new authorities would police political expression on their own initiative. And as this chapter and the previous ones have shown, the Old Regime and the Enlightenment bequeathed practices and principles to guide them in doing so.