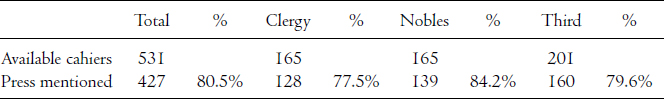

Table 4.1 Frequency of Demands concerning the Press

Individual freedom of thought must remain in accordance with the morality and manners of a people.

—Réponse aux instructions envoyées par S. A. S. monseigneur le duc d’Orléans, à ses chargés de procuration dans ses bailliages, relativement aux États-généraux, 1789

The turbulent conditions that Condorcet believed would justify restricting press freedom in his 1776 Fragments sur la liberté de la presse were precisely those reigning in France when this freedom was declared. Futile assemblies of intractable notables, an unbridled speculation war accompanied by a vicious libel war, pitiless calumny campaigns directed by and against ministers, the impending bankruptcy of the monarchy, and highly contested judicial reforms were rocking the Old Regime at its foundations, paralyzing government and sparking popular violence.1 Yet, amid the storm, calls for press freedom were made across the political spectrum, from the crown, clergy, and parlements to the most progressive elements of the nobility and third estate. Indeed, desire for this freedom was so widespread in 1789 that it is difficult to find signs of outright opposition to the principle.

But the devil was in the details. Demands for press freedom were often accompanied by demands for regulations and restrictions on it. We have seen that most philosophes and progressive royal administrators during the Old Regime were rarely naive in conceptualizing this freedom. Whether they saw it as a means for spreading enlightenment or regarded it as a pragmatic solution to an unstoppable clandestine print market, they nearly always envisaged limits. But what did communities throughout France think about press freedom on the eve of the meeting of the Estates-General, especially now that the monarchy had requested their opinion on the matter?2 How did local views trickle upward, if at all, in the series of meetings that began with local parish assemblies, corporations, and town councils, continued with primary assemblies where the general cahiers de doléances were drafted, and culminated in the National Assembly, which promulgated the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen in August 1789? Finally, what do the presence of limits on press freedom in the cahiers and their absence in the Declaration of Rights suggest about the problems revolutionaries later encountered in implementing this freedom?

In The Old Regime and the French Revolution, Alexis de Tocqueville expressed astonishment at having discovered in the cahiers de doléances a general desire to bring down the Old Regime. “I realized with something like consternation that what was being asked for was nothing short of the systematic, simultaneous abolition of all existing French laws and customs.”3 Tocqueville added that the drafters should have recalled the old dictum “Claim too great freedom, too much license, and too great subjection shall befall you!”4 However fitting this adage may have been for other demands, it was not warranted for free-press demands. Abuses of this freedom were precisely what a good many authors of cahiers sought to have punished, and they envisioned the reinforcement of Old Regime laws to do so.

Take, for example, the cahier drafted by the clergy of Villefranche-de-Rouergue. It called for “la liberté indéfinie de la presse” as a means to spread and advance enlightenment. Yet it also demanded that the names of publishers and authors appear on publications so that they could be held liable for works violating “the dominant religion, the general order, public decency, and citizens’ honor.”5 The nobles of Lille also expressed themselves in this forward- and backward-looking manner, calling for “the indefinite freedom of the press” by the “suppression of censorship,” followed by the requirement that the names of authors and printers appear on works so that they could be punished for statements contrary to “religion, the general order of things, public decency, and the honor of citizens.” They also demanded corporal punishment for distributors of foreign works containing reprehensible content.6 The third estate of Châtillon-sur-Seine touted the enlightened benefits of a free press but then coupled the demand for it with a call for the courts to punish writers and printers for publications contrary to “religion, mœurs, and the Constitution of the state.”7

Although historians have noted the great frequency of demands for a free press—indeed, such demands figure in over 80 percent of the general cahiers—they have tended to ignore the widespread desire for limits.8 Yet, not only did the vast majority of cahiers express desire for limits, the limits that were specified came straight from Old Regime press laws, the very laws historians often cite as proof of the lack of press freedom before 1789. The Book Trade Code of 1723, for example, threatened to punish “according to the rigor of ordinances” anyone involved in the production and distribution of “libels against religion, the service of the King, the good of the state, the purity of mœurs, and the honor and reputation of families and individuals.”9 The excessively repressive ordinance of 1757 imposed capital punishment on anyone involved in writing or distributing works that “attack religion, agitate spirits, undermine our authority, or disturb the order and tranquility of our states.”10 Restrictions on published statements attacking religion, mœurs, honor, the general order, and state authority—though absent from most of the pamphlet literature dealing with press freedom in spring 1789—appeared frequently in the cahiers.

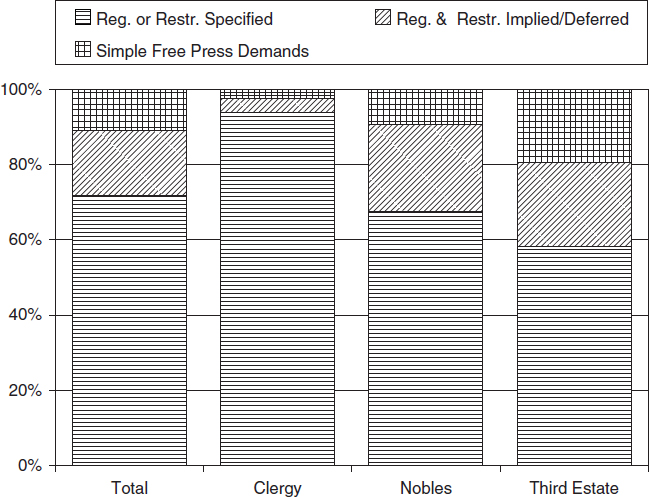

Desire for regulations and restrictions on press freedom is expressed in 89 percent of the general cahiers that mention the press. I consulted the available 531 general cahiers of the three orders: the clergy (165 cahiers), the nobles (165), and the third estate (201).11 General cahiers refer to those drafted by primary assemblies at the bailliage level.12 These assemblies also elected representatives who were responsible for carrying the general cahier to the meeting of the Estates-General in Versailles in May 1789. I also consulted the initial, lower-level (or local) cahiers of four densely populated areas: Paris, Rouen, Marseilles, and Aix-en-Provence.13 These local cahiers were drafted by corporations and parishes of the third estate (by bailliages secondaires in the case of Aix-en-Provence) and handed to representatives who subsequently convened in primary assemblies. What follows is a content analysis of the general cahiers of the three orders drafted by primary assemblies at the bailliage level and the preliminary, local cahiers of several cities or densely populated bailliages. In addition to calculating the frequency of demands for press freedom, I classified and counted demands for regulations and restrictions. Often, regulations and content restrictions were specified. In some cases, however, the cahiers expressed desire for them but deferred the task of determining them to the Estates-General, the king, or both. (See table 4.1 and figure 4.1.)

FIGURE 4.1 Kinds of free press demands

Although the question of limits on press freedom has not been overlooked by all historians of the cahiers de doléances, it has tended to be treated in passing or impressionistically.14 In her Le régime de la presse pendant la Révolution (1901), Alma Söderhjelm offered the most thorough discussion of limits to date.15 She read much into the differences in tone among the three orders’ demands. She saw the third estate out in front with the most radically formulated demands, the nobles following closely behind but trailing in enthusiasm, and the clergy divided on the matter. To illustrate the boldness of the third estate, she underlined the appearance in several of their cahiers of demands for “unlimited freedom of the press” (liberté illimitée de la presse), claiming that this phrase appears more frequently in the bourgeois cahiers than in those of the nobility (which is not true).16 Söderhjelm seems to have conflated unlimited with other superlative qualifiers such as absolute and indefinite since unlimited appears in only four documents.17 Moreover, whereas she construed unlimited to mean the absence of all restrictions and regulations, the nobles and third estate used all these superlative qualifiers—unlimited, indefinite, and absolute—in a temporal sense. This explains her puzzlement as to why such demands (appearing in 61 cahiers, by my count) frequently specified regulations and restrictions (appearing in 37 of the 61).18 She attributed this (apparent) contradiction to contemporaries’ inexperience with the concept: “People before the Revolution did not yet have a precise notion of what unlimited freedom of the press meant.”19 That may have been true, but they did have meanings that made sense to them, and a temporal interpretation of these qualifiers makes these demands intelligible. Given the monarchy’s provisional suspension of censorship in July 1788 for the sake of the upcoming meeting of the Estates-General, these qualifiers expressed a desire to prolong this suspension indefinitely. One can surmise this interpretation from the cahier by the nobles of Vitry-le-François, who called for “the most severe punishments against violators of the restrictions which must be legally applied to the indefinite freedom of the press.”20 Similarly, the nobles of Châlon-sur-Saône called for “the establishment of press freedom, indefinitely through the abolition of censorship, on the condition nevertheless that printers put their names on the works they publish and are held responsible, alone or with the author, for anything contrary to the dominant religion, the general order, public honor, and the honor of all citizens.”21

Many cahiers expressed an awareness that press freedom already existed and that the issue at hand was how to restrict and regulate it.22 The nobles of Châtillon-sur-Seine, for example, called for the abolition of all laws concerning censorship in their cahier. They observed, “This law, which is as pointless as it is impracticable, has consequently become entirely obsolete.”23 The clergy of Clermont-Ferrand asked the king to renew old regulations governing the press, “rather than legally authorize press freedom, which, in fact, already exists all too much and is degenerating into license.”24 Likewise, the clergy of Dôle seemed to view this freedom as a sad reality when it requested that “the police watch over the freedom of the press with more circumspection.”25

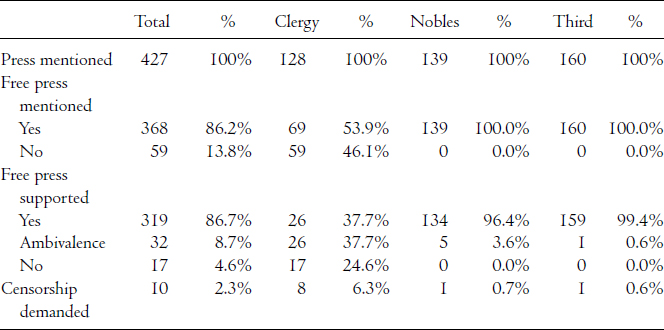

Of the three orders, the clergy was, as Söderhjelm noted, least enthused about press freedom (see table 4.2). They railed against the “prodigious quantities of scandalous works, the unfortunate fruit of a love of independence.”26 They bemoaned the underground market of “perverse” works, convinced that it was “altering all religious and political principles” and “delivering fatal blows to faith and mœurs.”27 Some complained that bad books were “poisoning” the countryside, “corrupting morals, spreading discord within families, provoking tensions between the different estates, and causing divorces to multiply.”28

Table 4.2 Dispositions toward Press Freedom

Percentages in the top half are based on the number of cahiers mentioning the press. Percentages in the bottom half are based on the number of cahiers mentioning the freedom of the press.

Yet for all the clergy’s alarm about press freedom, only 17 of their cahiers explicitly opposed it (see table 4.2). Twenty-six clerical cahiers, in fact, demanded it, sometimes singing its praises.29 Only 8 clerical cahiers, along with 1 noble cahier and 1 by the third estate, insisted on censorship.30 Even in these cases, they envisaged significant reforms. For example, the clergy in Amiens called for the establishment of a committee of three censors composed of an honest magistrate, an incorruptible man of letters, and a rigorous theologian. The clergy of Le Mantes pressed for postpublication censorship by Church officials, demanding that they be authorized to conduct random inspections of print shops and that they be in charge of reading all new publications, denouncing bad ones to the Public Ministry, which would be responsible for bringing the affair before the courts. In the only third-estate cahier calling for censorship, the bourgeoisie of Libourne supposed that the Provincial Estates would assume the responsibility of authorizing publications. Only three of the ten general cahiers that called for censorship did not propose significant changes to the old system.31 This is an eloquent indication that for prerevolutionaries, Old Regime censorship was dead.

Among the 427 general cahiers mentioning the press, there are two that, despite their exceptional length, exemplify the way Enlightenment optimism about press freedom could be combined with demands for regulations and restrictions. These cahiers give extended articulation, I believe, to widespread notions about legitimate limits. None went further than the nobles of Châtillon-sur-Seine. They began their cahier praising the press for having spread a spirit of critical reflection and enlightened ideas about justice.32 They underlined how the press helped inform and guide administrators in carrying out their duties but believed that censorship discouraged many individuals with useful knowledge from publishing it. Administrators, they argued, often received this information only when it became imperative to obtain it, if at all. By definitively abolishing prepublication censorship and facilitating the flow of information, press freedom, these nobles insisted, would improve the functioning of government.

The nobles of Châtillon-sur-Seine then outlined regulations and restrictions. They recommended that writers register their manuscripts with royal notaries in the districts where they intended to have their works published (an idea that appears in three other noble cahiers as well).33 The printers of registered works were not to be held responsible for criminal content. (This also appears in several other cahiers.) The author alone was to bear responsibility, a measure that would have satisfied not only Voltaire, who believed that authors should be free to have their works published at their own profit and risk, but Malesherbes as well, as we have seen. If, however, the printer chose to publish an unregistered work, he and the author would be held jointly responsible. Finally, after the printing of the manuscript, the author and printer were to sign a declaration asserting that the printed version conformed to the original manuscript.

These were already elaborate regulations. But there was more. The nobles of Châtillon-sur-Seine insisted that any writer found to have insulted religion, the law, the king, or the nation or whose works provoked divisions among the people was to be punished according to “the rigor of laws which already exist or that the Estates-General chooses to modify or create.” Thus, this cahier not only called for maintaining the harsh jurisprudence for injurious speech; it authorized the Estates-General to make it harsher if they so desired.

The cahier of the third estate of Vézelise also combined Enlightenment optimism with Old Regime restrictions, though with less stress put on punishment. They asserted that press freedom was necessary for a people to be truly free.34 The interests of the king and the people, they believed, would be advanced by the truth that a free press would bring to light. After several lofty paragraphs about the virtues of press freedom, the authors began slinging mud at the king’s ministers, declaring that truth is only disadvantageous to such men who amass personal fortunes on the ruins of the state. Man’s dignity, they insisted, requires that he be free to act against ministerial corruption.35 After lambasting ministers, the bourgeoisie of Vézelise turned their attention to libels. They called for “the erection of barriers against this torrent of scandalous writings that cultivates a taste for libertinage . . . leading men away from their responsibilities as citizens.” In this, they sounded much like the clergy. They also sounded like the many midcentury philosophes who believed that good mœurs were the sine qua non of stable, flourishing societies. Once mœurs were corrupted, so they believed, only state force could prevent society from sliding into anarchy.36

All this appeared in the preamble to concrete demands, the first of which was quite typical: “the freedom of the press, except for libels and obscenities that will be dealt with by the law.” Subsequent articles, however, departed from cahier norms in proposing the establishment of provincial committees in charge of monitoring all books concerning mœurs, history, philosophy, ethics, and fiction. The authors of good books were to be rewarded; those of bad ones were to be declared “bad citizens.” The proposal clearly smacks of censorship, but not of the prepublication kind. It chimed with Thiébault’s recommendations, as well as with the civil censorship described by Montesquieu and Rousseau. Unlike the nobles of Châtillon-sur-Seine, though, the bourgeoisie of Vézelise called for gentle punishment for press abuses. In the spirit of Rousseau’s Lettre à d’Alembert, they called for bad authors to be publicly humiliated rather than banished, imprisoned, or executed.

Most cahiers, however, did not envisage mitigated punishment for criminal expression. To the contrary, many insisted on harsh sentences. Explicit punitive language can be found in sixty-six cahiers (15.5 percent of those mentioning the press), slightly more than the number of cahiers containing enlightened arguments about the benefits of a free press (11 percent).37 The third estate of Orléans, for example, urged the Estates-General to fix “a solemn law prohibiting, with the most rigorous of punishments, writings attacking religion, mœurs, the respect due to the sacred person of the King and the honor of citizens.”38 With the reticence characteristic of a good many clerical cahiers, the clergy of Nancy urged that, if the Estates-General decide that press freedom is a measure necessary for political liberty, they should nevertheless “take severe precautions to prevent abuses by imposing grave punishments.”39 Especially harsh, the third estate of Monteuil-sur-Mer and the nobility of Lille demanded corporal punishment for offenses.40 Most cahiers, though, were vague about punishment, calling simply for “due punishment.”

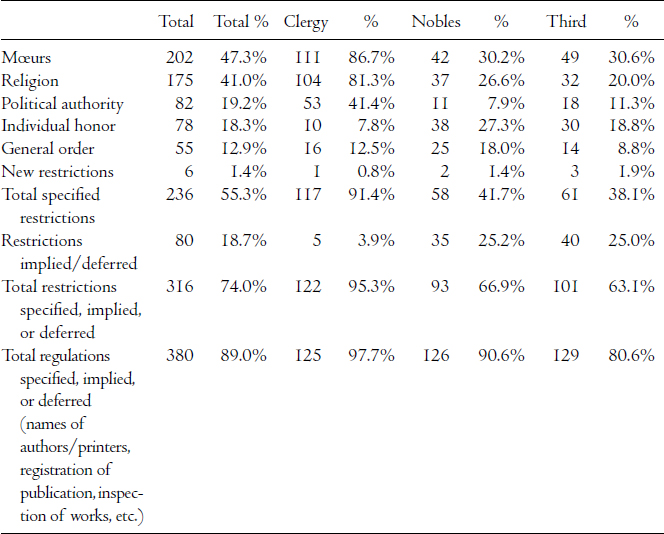

What abuses were the authors of the cahiers most concerned about? Mœurs figured most frequently among all three orders (see figure 4.2). Among the clerical cahiers, mœurs was mentioned even more often than religion! Religion, though, was the second most frequently stated concern for the clergy and third estate, although it ranked third among the nobles, who expressed more concern about attacks on individual honor. Such attacks ranked third on the list of limits demanded by the third estate. In contrast, the clerical cahiers hardly mentioned honor at all. After mœurs and religion, the clergy’s most frequently cited concern was libels against the government and the constitution—or, more generally, political authority. This concern appeared in roughly 40 percent of their cahiers that discussed the press. Political authority was much less frequently mentioned by the nobility (8 percent) and the third estate (11 percent). This suggests that the latter two orders viewed press freedom as a vehicle for challenging traditional institutions of authority. (See table 4.3 and figure 4.2 for the relative frequencies of cited restrictions for each order.)

Table 4.3 Regulations and Content Restrictions

Percentages are based on the number of cahiers mentioning the press for each order.

The only novel restrictions appearing in the cahiers were “the rights of other individuals” (les droits d’autrui), which appeared in three cahiers, one from each estate, and “respect for the nation,” also found in three cahiers, one by the nobles and two by the third estate.41 All but two of these six cahiers combined these categories with Old Regime restrictions. Of the two cahiers that contain only these new content restrictions, one was written by Condorcet and is frequently cited in studies of the cahiers.42 Clearly, though, it was not representative of the spirit of the general cahiers.

The reason historians have so often overlooked the widespread desire for limits on press freedom on the eve of the Revolution may have to do with the fact that such limits hardly appear in the cahiers they most often cite, namely, those of the third estate of the most densely populated bailliages in France: Paris, Marseille, Rouen, Lyon (ville), Bordeaux, and Aix-en-Provence. One might suppose that, given the prominence of the press in these areas, the public had become inured to abuses and did not worry about them. Close inspection of the preliminary cahiers drafted at the level of parishes and corporations in these cities, however, suggests otherwise.

Consider Rouen. The fifth largest in France, the city had a particularly active bourgeoisie in the spring of 1789.43 Of the sixty-two corporations that drafted cahiers, only twelve demanded a free press, five of which came from the legal professions.44 Formulations ranged from straightforward (the procureurs au parlement requested simply “the freedom of the press”) to cautious (the notaires added restrictions to protect citizens’ honor and public order). Five of the twenty-eight artisans’ guilds (watchmakers, grocers, stockings fabricants, small-wares makers, and mirror makers) demanded press freedom. Surprisingly, their demands were often more elaborate than those made by the legal corporations. For example, none of the legal corporations came close to phrasing a demand as developed as the one by the watchmakers’ guild.

The burdens placed on printers make us dependent on foreign works. The sums of money . . . sacrificed to procure forbidden books would be better spent rewarding acts of virtue or encouraging manufacturing. . . . [Our] mœurs gain nothing from the more or less spectacular prohibition [of books]. The nation is gratuitously deprived of the enlightenment that press freedom would spread concerning aspects of administration and notably, concerning the virtues of each of its members in whom this enlightenment has been entrusted.45

For their part, the stocking fabricants adopted a more punitive tone, calling for rigorous prosecution of writers, printers, and distributors who abused press freedom. They also proposed ecclesiastical censorship of texts concerning religion.46

Among the parishes on the outskirts of Rouen, free-press demands were made far less frequently, appearing in 4 of 153 cahiers. Yet, these cahiers express more originality and frankness than those drafted by higher assemblies. The small farming village of Duclair outside Rouen wrote, “We’re no longer worried about the freedom of the press; abuses exist, of course, but prohibitions have done nothing to stop bad books anyway, and they’ve done much to stop good ones.”47 The other three cahiers were explicit about restrictions, especially on works threatening public order. The cahier of Saint Paul, which had only 271 inhabitants, called for press freedom but warned that it might be imprudent to grant it without restrictions; its authors underscored the current climate as proof: “The effervescence of the present revolution attests to the dangers [of unrestrained libels].”48 In the spring of 1789, then, peasants saw themselves already swept up in the excesses of a revolution! This cahier also confirms what the clergy bemoaned—the spread of “philosophie” into the countryside.

How were all of these formulations synthesized in the general cahier of Rouen? Both the city of Rouen (which was accorded exceptional general-cahier status) and the bailliage proclaimed, “The freedom to communicate ideas is an essential aspect of personal freedom. . . . All citizens are permitted to have their works printed without having to submit to censorship . . . excepting the qualifications and modifications that the Estates-General chose to impose.”49 Thus, the concrete regulations and restrictions that were specified in the cahiers drafted at lower levels were omitted and the task of defining them left to the Estates-General.

Limits on press freedom were also omitted from the general cahier of Marseilles. Eight of fifty-one corporations in that city demanded press freedom with great diversity in tone and specified restrictions. Yet, the general cahier demanded “the freedom of the press, except for restrictions that the Estates-General might impose.”50 In Paris, free-press demands were made in many district cahiers.51 Again, formulations range widely, from tepid assent to bold insistence. In a curious and radical departure from cahier norms, the district of Théatins claimed that press freedom would be jeopardized if printers were held responsible for content and authors were required to declare their names. The district assured that there were “already enough means to track down and punish the authors of libels.”52 In any case, like the general cahiers of Rouen and Marseilles, specific restrictions were left out of the general cahier of Paris (intro muros), which insisted only on holding authors and printers responsible “for the consequences of their writings.”53 The general cahiers of Bordeaux, Lyon (ville), and Nantes also avoided specifying regulations and restrictions in their demands for press freedom.54

It appears, then, that in densely populated places where demands went through a succession of assembly debates before being inscribed in a final general cahier, limits were omitted. Why? One might suppose that the plethora of published pamphlets at the time—notably, the many instructions, memoranda, and model cahiers—had influenced the primary assemblies of densely populated areas. These pamphlets rarely mentioned limits in demanding press freedom, and even when they did, their authors (mostly noble) were concerned about protecting honor more often than religion or mœurs. Writers in the spring of 1789 knew that a world was opening up in which they might exert political influence. They therefore had little interest in limits. Why insist on restrictions that might be turned against oneself?

This is precisely what happened to Alexandre de Lauzières de Thémines, Bishop of Blois. In calling for limits on press freedom, he put himself in the predicament that most writers avoided. His model cahier, Instructions et cahier du hameau du Madon, dealt with, among other issues, fiscal reforms. It was above all a scathing indictment of the Calonne ministry. Thémines took this occasion to outline his views on press freedom. He stated that the freedom to think should not be confused with the freedom to publish. “If each individual is master of his own opinion, this does not put him in charge of public instruction and policing.” He offered an analogy:

Imagine if a foreigner came to France to find as many philosophical systems, religions, and political agendas as there are people; if he found everywhere—even on the stairs of the palace of Versailles—the brochures and libels of the day; if he went to the location where a great number of people are [regularly] defamed under the noble pretext of patriotism; one would call the universe into question. . . . Property, life, and the honor of citizens should be under the protection of the law . . . in all well-administered [policées] nations there must be respected regulations of which the first article should be to punish all clandestine works.55

Thémines proposed establishing a system of surveillance within the Public Ministry office, not unlike the systems proposed by Rousseau and Thiébault. This aréopage, or learned assembly, would keep an eye on publications and alert the minister to dangerous works so that judicial action might be taken. Slandered individuals would not have to suffer financial ruin from legal fees since the Public Minister would pursue affairs involving defamation.

Yet, defamation is precisely what Calonne, the disgraced former minister of Louis XVI, accused Thémines of spreading. In his published response, Calonne turned the Bishop of Blois’s principles against him:

You should be judged, Monsieur, by your own maxims. What would you say before the aréopage you insist on establishing to punish the authors of defamatory pamphlets? How would you respond to the Public Minister whose task, you propose, would be to avenge the honor of citizens?56

Most writers were more prudent than Thémines. They remained vague about limits on press freedom. With tensions so high and power not yet secured (the Bishop may have assumed he still had unquestioned authority), it was not wise to insist on regulations and restrictions.

Does the marked absence of demands for limits on press freedom in most of the pamphlet literature explain the marked absence of such demands in the general cahiers from densely populated urban areas? It is difficult to tell, but in reading hundreds of cahiers and nearly four dozen pamphlets deemed to have been influential in the spring of 1789, I have occasionally discovered strong textual similarities that suggest that the authors of the cahiers living in bailliages far from each other were inspired by the same pamphlets. For example, the nobles of Armagnac in the southwest, the nobles of Poitiers in the center-west, and those of Châlons-sur-Saône in the Burgundian center, together with the third estates of Metz in the northeast and Villers-Cotterets just east of Paris, all used the same syntax and lexicon to demand “the indefinite freedom of the press, absolute by the abolition of censorship.”57 (It is rare to find the abolition of censorship mentioned explicitly in the cahiers.) They all required the name of the printer on works and held the printer and author jointly responsible for content, and four of the five mentioned specified content restrictions using the same lexicon and sequence, desiring the repression of writings attacking “the dominant religion, the general order, public decency, and the honor of citizens.” (“The dominant religion” and “the general order” were commonly mentioned restrictions in the cahiers but usually formulated differently.)

For all their textual similarities, subtle differences among these cahiers suggest that, even if the authors of these cahiers borrowed from the same pamphlet, they did so selectively. Of the five similar cahiers mentioned above, the one from Poitiers added two restrictions not found in the others: on writings that undermined “the constitution and the laws of the realm” and “respect for the king.” Moreover, one cahier asserted that press freedom was rooted in individual liberty, a claim found in the instructions circulated in the name of the duc d’Orléans, but not in the other four cahiers of the group.58 I also discovered lexical similarities between a widely circulated pamphlet and the cahier by the clergy of Autun. Both requested press freedom for discussions concerning administration, “because the affairs of the state are the affairs of each person.”59 A notable difference, though, is that unlike the pamphlet, the cahier added restrictions: “except for attacks on religion, mœurs, and the rights of others.”

Clearly, then, the authors of most general cahiers did not allow themselves to be swept up by the more liberal formulations of press freedom found in the pamphlet literature. They wanted and expected limits. But why, then, did the general cahiers of densely populated bailliages such as Rouen, Paris, Marseilles, and others refrain from specifying limits? It is impossible to know for certain, but if what occurred in the National Assembly that summer during debates on the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen sheds any light on the matter, the reason may have had to do with the inability of deputies in primary assemblies, particularly large ones, to agree on what limits should be implemented. The greater the political stakes and the greater the number of deputies assembled, the less likely it was that consensus on limiting press freedom would be reached.

Between May and August 1789, the freedom of the press went from being an item on the agenda for reforming the administration to becoming an inalienable and universal right of the citizen. Seeking to bolster its own legitimacy and determine the guiding principles for a new constitution, the National Assembly decided to issue a declaration of rights.60 Debates on the final wording of Articles 10 and 11 of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, which dealt with religious freedom and free expression, reveal the difficulty involved in reaching compromise. Rhetorically strident, these articles show that deputies hedged their bets, tempering bold principles with precautionary clauses. These clauses were vague, however, since national deputies could not agree on how to reconcile free speech with the protection of other core values, particularly religion and mœurs.

The ambivalence of deputies on the issue of limiting press freedom in August had been preceded by months of ambivalence on the part of the monarchy. Since the spring, the crown had been giving mixed signals about its tolerance threshold. In April, it renewed all prior laws and ordinances governing the press.61 A month later, the king’s Conseil d’État ordered the shutdown of Brissot’s and Mirabeau’s unauthorized newspapers and increased police surveillance. Still, press freedom remained on the official agenda, and on May 19 the garde des sceaux, ceding to public pressure, authorized journalists to cover the meeting of the Estates-General, provided they withheld commentary.62 On June 23, just days after the Estates-General transformed itself into the National Assembly, deputies reminded the king during his royal session with them that the problem of press freedom still needed to be resolved.63

In July and August, the problem became imbricated in the larger issue of a declaration of rights. The first proposed declaration in the National Assembly was made by Gilbert du Motier, marquis de Lafayette, on July 11. Drawing inspiration from certain state constitutions of the United States, Lafayette avoided mentioning restrictions.64 He asserted that certain rights were inalienable, among them the freedom of opinion and of communication “by any available means.”65 Over the next month and a half, dozens of other proposals streamed into the National Assembly, which set up several committees to review them and to draft model declarations that would be discussed and voted on by the whole Assembly.

How did these proposals envision press freedom? Like the cahiers, they advanced a variety of formulations. Among the 32 proposals assembled by Antoine de Baecque, Wolgang Schmale, and Michel Vovelle, 14 mentioned Old Regime restrictions: 5 invoked religion, 4 mœurs, 7 public order and tranquility, 6 the honor of citizens, and 3 respect for political authority. However, whereas only 3 general cahiers from all over France had mentioned “the rights of other individuals” (les droits d’autrui), 16 model declarations did so. Clearly, this marks an important shift in how limits were being conceived; rather than framing them in terms of traditional collective values, such as morality and religion, les droits d’autrui suggested a more liberal approach, focusing on the individual. Though novel and clearly modern, the concept of les droits d’autrui would not work its way into a declaration of rights until June 1793.66

Taken together, specified regulations and restrictions appeared in 21 of the 32 proposals. In addition to these, 6 proposals said nothing about the press, including, ironically, the one proposed by future radical journalist Jean-Paul Marat. Another 3 proposals did allude to limits but deferred defining them to the Constitution.67 Aside from Lafayette’s proposal, there remains an anonymous one that called simply for the author’s name to appear on published works.

A noteworthy difference between the cahiers de doléances and declaration proposals was the position of specified limits in the overall document. While many of the rights proposals sounded more stridently liberal than the cahiers in articulating press freedom, restrictions often crept into adjacent articles. For example, Article 13 of Jérôme Pétion de Villeneuve’s proposal seems unambiguous: “Each individual may write and publicize his thoughts; one should no more obstruct the development of intellectual faculties than the development of physical faculties.” In a prior article, however, he stated that individual freedom could be limited by the law, and indeed, he called for laws to repress religious opinions that disturbed “public tranquility.”68 Étienne-François Sallé de Choux (who, like Pétion, would eventually sit on the left in the National Assembly), in his proposed article on press freedom, invoked only les droits d’autrui. However, in an earlier article, he called for the law to specify duties as well as rights. “Given the clash of passions fueled by particular interests that can disturb society and even overthrow it, laws are necessary to determine the rights and obligations of all members, to put restraints on those who refuse to respect them.”69 He warned about secret transgressions that might elude the law and stressed the need for religion, “which alone can repress such crimes by ruling over hearts.” Similarly, under the rubric “the rights of citizens,” the future left-wing deputy Arnaud-Raymond Gouges-Cartou called for the freedom of ideas and their communication, the sole restriction being attacks on les droits d’autrui. However, in a subsequent article under “the rights of societies,” he referred to “secret crimes” on the moral level that only religion and moral instruction could prevent.70 Although such qualifications do not amount to legal restrictions on speech, they suggest that these deputies expected religious and moral institutions to discipline thoughts and speech as a prior condition to enjoying freedom responsibly.

Two other proposals also viewed religion and mœurs as prior to positive law.71 Preceding an article declaring the right to communicate and publicize ideas freely for any subject “not proscribed by the law,” the future Girondin J. M. A. Servan insisted on the importance of religion in shaping opinion, even as he tried to define religion in broad, confessionally neutral terms.

Religious laws conform to civil liberty when, in prescribing moral actions beneficial to all, they impose a cult and dogma only to the degree that is necessary to secure the [more universal] principles of morality. . . . Laws [those prior to positive law], and especially the law of opinion, secure civil liberty when, for actions that positive law does not prescribe, each individual directs his actions toward the public good defined by the law of opinion which chastises through shame and rewards through esteem.72

Like many midcentury philosophes concerned with civic morality, Servan thought that religion encouraged people to consider the general good. Alongside religion figured a second source of morality: public opinion. Servan viewed public opinion not just as a well of ideas from which authorities would draw to make policy, but as a moral regulating force as well. His ideas reveal the strains involved in trying to reconcile the preservation of civic mœurs through religion on the one hand and the granting of religious freedom on the other.

On August 4, the day feudal privileges were abolished, the National Assembly voted against a declaration of duties. Whereas before, restrictions on free speech had fallen neatly into the “duties” column of proposals, they were now inserted into articles on the right to freedom of opinion and of expression. On August 19, the comte de Mirabeau presented a draft on behalf of the comité du cinq. It called for limits on expression that violated the rights of other individuals.73 The National Assembly rejected it. According to Marcel Gauchet, deputies criticized the draft for not protecting religion. It did not call for the establishment of a public cult, failed to declare religion the guarantor of mœurs, and did not even acknowledge God as the inspiration for the declaration’s principles.74 Pressed for a new model, deputies chose an obscure one written earlier that month by one of the Assembly’s thirty bureaus, the sixième. Contrary to the comité du cinq’s draft, this one was infused with religion.

Debate on the freedom of opinion and of religious expression began on Saturday, August 22, and quickly became tumultuous.75 Despite pleas by the National Assembly’s president at the start of the session to remain calm, deputies were at each other’s throats, and the president threatened twice to step down. By the end of the day, the Assembly had reached no agreement. On the twenty-third, the duc de Castellane presented a more liberal and laconic article than those discussed the day before. He proposed that “no one be disturbed for his religious opinions or bothered in the exercise of his cult.”76 The proposal stirred up a storm of opposition, and the “public order” clause was put back on the table. Mirabeau opposed the clause. He insisted that religious cults should not be policed, even if, he added bitingly, the Roman emperors Nero and Domitian had done so to crush the nascent Christian movement. Mirabeau’s sarcastic point was reinforced by the more sober arguments of Jean-Paul Rabaut Saint-Étienne who, speaking on behalf of his many Protestant constituents in Nîmes, called for the absolute freedom to express any religious opinion. But the majority insisted on maintaining the “public order” clause, which clearly implied the maintenance of orthodox religion.77 Many worried that extending civil equality to Protestants would provoke sectarian strife, observing that the specter of the sixteenth-century Wars of Religion still haunted contemporary imaginations.78

By the end of the day on August 23, the National Assembly agreed to declare the freedom of religious opinion but stopped short of approving the freedom of public worship. Article 10 read, “No one should be disturbed for his opinions, even religious ones, provided that their manifestation does not disturb public order as determined by the law.”79 Ultimately, the article did not advance the cause of religious minorities much further than the 1787 edict recognizing Protestant property and marriage rights. Like the edict, the article did not grant full civil status to Protestants or the right to hold administrative offices and teaching positions.80 Many deputies were dissatisfied with the article, and it was criticized in the press.81 Still, the final formulation of the article was a good deal more tolerant than the sixième bureau’s original proposal. Although the bureau had been quite progressive with regard to press freedom, calling for limits only on violations of les droits d’autrui, it had approached religious freedom with less verve, qualifying this freedom in three articles, none of which exuded religious tolerance. The first article insisted on the necessity of religion in order to strike down “secret crimes” occurring in one’s moral conscience that might otherwise remain beyond the grip of the law and undermine the “good order” of society. The second declared Catholicism the official national cult. The third protected alternative religious opinions from repression, provided they did not disturb the public order. In the end, the National Assembly approved only the third proposition.

It was clear to religious pluralists, of course, that the “public order” clause was sufficiently vague to be pressed into the service of Catholic hegemony, especially if legislators were to subsequently declare Catholicism the official religion of France.82 The next day, August 24, a deputy tried to reverse the situation by proposing to replace the ordre public clause with les droits d’autrui, but modifications to articles already adopted were not permitted. The discussion then turned to Article 11, the freedom of expression. Again, the sixième bureau’s proposal served as a starting point for discussion: “The free communication of ideas being a right of the citizen, it must not be restricted in so far as it does not infringe on the rights of others.”83 This qualification—les droits d’autrui—which had been rejected the day before by conservative deputies in the article concerning the freedom of religious opinion, now served as the starting point for debate on free expression. It would be rejected again.

The National Assembly reached consensus on the first part of the article, which concerned the freedom to communicate ideas. The latter part, which concerned limits, sparked intense debate. François-Alexandre-Frédéric, duc de la Rochefoucauld-Liancourt proposed altering it, making authors accountable “for the abusive use of this freedom, as prescribed by the law.” Rabaut Saint-Étienne warned that the clause was too vague and would lead to inquisitions and censorship. He tried to recover the droits d’autrui clause. Another deputy suggested the inclusion of both clauses, but the majority squawked. A few deputies questioned whether restrictions should even be included in a declaration of rights. Robespierre thought that all restrictive limits should be confined to the Constitution.84 “Abuses pertain only to penal law. . . . All restrictions, all exceptions to the exercise of rights must be taken up in the Constitution.”85 This suggestion polarized the Assembly further. Mirabeau then intervened and reframed the whole debate. Rather than argue about whether limits should be mentioned in the declaration of rights, he questioned whether they should be treated as restrictions (which, he warned, would lead to new forms of censorship) or, as he preferred, repression, applied after publication in cases of criminal content. Like other progressives at the time, Mirabeau conceived of press freedom as compatible with ex post facto punishment. “We give you a desk to write a calumnious letter, a press for a libel; you must be punished once the crime is committed: it is a matter of repression, not restrictions; it is the crime one punishes, and the freedom of men should not be hampered under the pretext that they might want to commit crimes.”86 The discussion now moved toward consensus. Despite two final attempts to pull the article in conservative and liberal directions, Mirabeau prevailed. The article on free expression passed in the following terms: “The free communication of ideas and opinions is one of the most precious rights of man. Each citizen may therefore speak, write, and print freely, while nevertheless being held accountable for abuses of this freedom in such cases as are determined by the law.”87

In the end, then, the National Assembly opted to authorize punishment for abusive, criminal speech. But it postponed defining what constituted an abuse. Would abuses be limited to attacks on the rights of other individuals (les droits d’autrui)? Or would they encompass attacks on collective moral and religious values, as so many cahiers had insisted and a good number of deputies still wished?

In his 1788 book, De l’importance des idées religieuses, Jacques Necker, a Protestant and Louis XVI’s Director General of Finances, defined the aims of legislation: “Wise laws should have two major objectives: maintaining public order and the happiness of individuals; but to achieve them, the aid of religion is absolutely necessary.”88 For Necker, Christianity preceded positive law and was even more important than public opinion, whose authority he had done so much to promote in recent years.89 Unlike laws or public opinion, religion, he now argued, had the advantage of being able to “reach into the secrets of our hearts.”90 “By their influence on mœurs,” he continued, religious opinions “produce an infinite number of good acts.”91 Necker was not alone in thinking so. As we have seen, this view was common during the eighteenth century, even among many enlightened philosophes.

Similar views, though less confessionally elastic, were propounded by the Bishop of Nancy, Anne-Louis-Henri de La Fare. In his opening sermon at the meeting of the Estates-General on May 4, 1789, La Fare insisted that religion was the basis of happiness and urged that it remain the sacred foundation of the reformed state. (La Fare would head the sixième bureau that proposed establishing Catholicism as the exclusive national cult, and he would later become an active counterrevolutionary.) Apparently, La Fare’s views were enthusiastically received by the monarchy, clergy, third estate, and newspaper press. (The response of nobles was mixed.)92 As the preponderant mention of religion and mœurs in demands for press freedom in the cahiers de doléances suggests, the importance Necker and La Fare gave to religion chimed with public sentiment.

In the summer of 1789, conservative and progressive deputies in the National Assembly advanced declaration proposals that included restrictions on free expression to protect religion and the general order. Particularly revealing about the widespread nature of such concerns, three of the four proposals that emphasized the important role of religion in shaping civic values were written by deputies who would later sit on the left (Servan, Gouges-Cartou, and Sallé de Choux; the fourth was anonymous). The belief that religion and mœurs constituted the mutually reinforcing twin pillars of a stable order underwent its first serious challenge in discussions on the Declaration of Rights, just as factions were beginning to form in the National Assembly. The division was discernible in debate over Article 10. Although the supporters of religious orthodoxy failed to get their views inscribed in the Declaration of Rights, the “public order” clauses in Articles 10 and 11 left open the possibility that “public order” would later be defined as a Catholic moral order. Attempts to declare Catholicism the national cult were indeed made over the next year. The defenders of religious freedom worried, not without reason, that Catholic hegemony over public morality would favor the forces seeking to reverse the Revolution. Still, like their adversaries, progressives believed that good mœurs required tutelage. The problem was that they had no alternative moral paradigm to Catholicism and no institution other than the Catholic Church to rely upon.

Thus, a raw nerve in revolutionary politics stretched across religion and mœurs. If Jacobins would later become obsessed with morally regenerating society through new secular principles, it was clear from the outset that many wanted to keep society under the moral sway of the Catholic Church. And there were compelling reasons for keeping it there, especially as privileges were being abolished and feudal documents, not to mention châteaux, were going up in smoke. But what would happen once clerics began using religion to stir up popular opinion against the Revolution over the next two years—against policies that extended citizenship to non-Catholics, deprived the Church of its vast wealth, and blocked the creation of an official national religion? As we shall see, revolutionaries would eventually detach mœurs from religion and seek new secular moorings for them. They would invoke public spirit, the law—even the Revolution itself—as the bases of their new civil religion. Fighting fire with fire, they would spread these values with evangelical fervor, invoking them to justify their efforts to consolidate punitive authority in the state. But as the cahiers de doléances of 1789 suggest, the repression of bad mœurs was already deemed legitimate and necessary by much of French society.

In any case, the war over the sacred underpinnings of the new order would break out later, beginning in the spring of 1790. For now, in August of 1789, revolutionaries managed to reach a compromise on free speech. They abolished what was widely held to be an inefficient and arbitrary, though essentially defunct, press regime. But even as they drove nails into the coffin of prepublication censorship, they tempered their bid for freedom—and ultimately undermined it—calling for the repression of abuses that they failed to define.