FIGURE 6.1. Massacre des patriotes de Montauban. Courtesy of the Carnavalet Museum. Unlike in Nîmes, where hundreds died in sectarian violence, few were actually killed in Montauban.

When legislators protected the freedom of religious opinions [in 1789], it never entered their minds to allow all religions to be free, except for one, the religion that has been the national religion for more than twelve hundred years.

—Deputy-bishops of the National Assembly, October 30, 1790

On the morning of October 21, 1790, the comte de Mirabeau thundered at the podium in the National Assembly. Debate concerned a measure that would require the French Navy to raise the revolutionary tricolor flag instead of the traditional white one. In arguing for the revolutionary ensign, Mirabeau excoriated the opposition in terms that amounted to an accusation of treason.

I demand a judgment. I insist that it is not only disrespectful or unconstitutional to question [the tricolor flag]. I insist that it is profoundly criminal. . . . I denounce as seditious conspirators those who would speak of maintaining old prejudices. . . . No, my fellow deputies, these tricolors will sail the seas; [they will] earn the respect of all countries and strike terror in the hearts of conspirators and tyrants.1

Mirabeau’s incendiary speech riled the opposition, prompting one deputy on the right, Jean-François-César de Guilhermy, to mutter injurious epithets. Overhearing them, Mirabeau’s allies demanded Guilhermy’s arrest, “for the honor of the National Assembly.”2 After a vote—and, as evidence suggests, communication between individuals in the Assembly and crowds outside—the deputies expelled Guilhermy for three days, keeping him under house arrest during that time. Mirabeau endorsed the measure. Despite having championed the freedom of expression and the inviolability of deputies the year before, he now reasoned, “It is not fitting for a deputy to sacrifice the portion of respect due to him as a member of this Assembly.”3

Guilhermy was one of four deputies condemned for speech in the Constituent Assembly in 1790. Three were put under arrest; a fourth was pardoned. Temporary arrests were not the only form of exclusion. In the spring of that year, François-Henri, comte de Virieu was pressured into stepping down as president of the National Assembly for having signed and circulated a declaration protesting a recent decree, thereby violating an oath. To be sure, these exclusions were mild compared to the deadly ones carried out three years later; punishments ranged from three- and eight-day house arrests to three days in prison. Still, they suggest that alongside liberal reforms, illiberal practices were seeping into high politics. Nor was the illiberal nature of these exclusions lost on the deputies of the losing side (in all cases, right-wing deputies). In their view, these exclusions ran counter to the Assembly’s professed commitment to free speech. Worse, they had no basis in law. Although deputies had set rules governing Assembly discipline in the summer of 1789, they had not agreed on authorizing arrests of members. A motion calling for the temporary arrest of obstreperous deputies was advanced in June 1790 but was rejected.4

What prompted these exclusions in the Constituent Assembly? Few historical studies of the early Revolution acknowledge that they even occurred. These incidents run counter to the prevailing view of the “liberal phase” of the French Revolution. According to this view, national deputies are seen keeping their extremist elements in check, conducting debate “without imputations of disloyalty or treason,” and remaining above the fray of popular passions, at least after October 1789.5 Before then, of course, the storming of the Bastille on July 14, rural attacks on noble property in the following weeks, and the Women’s Bread March to Versailles in early October helped progressive deputies push through liberal reforms, notably, the abolition of feudalism and the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen. But from late 1789 until September 1791, the high politics of the Constituent Assembly are depicted as just that, high. As one historian has recently asserted—and most accounts concur on this point—in this period, “[Popular] terror spread at the bottom without ever contaminating the high reaches of the state,” even when it would have been easy and opportune for leaders to exploit it.6

But leaders did exploit it. While patriot deputies courted crowds gathered outside the National Assembly in Paris, reactionary deputies capitalized on, even fomented, sectarian agitation in the provinces. Moreover, noble deputies injected their own form of violence, the duel, into revolutionary politics, where it mixed with popular punitive dynamics. In the course of interactions between the National Assembly and society, religion, oaths, and honor played important roles. Deeply engrained in Old Regime culture, religion, oaths, and honor provided familiar idioms for defining the legitimate limits of opposition and customary practices for preventing and structuring conflict. To be sure, these practices and social idioms were not inherently radicalizing forces. During the Old Regime, they had helped affirm allegiances, reinforce hierarchical power relations, and structure patterns of esteem and deference. During the Revolution, however, they polarized politics, lowered tolerance thresholds, and generated punitive, exclusionary impulses. They had markedly illiberal consequences for free speech.7

The first attempt to arrest a deputy in the National Assembly for speech occurred on December 15, 1789. The Assembly was considering whether the Parlement of Rennes had obstructed the Assembly’s efforts to reform the justice system (the creation of a system of elected judges was on the agenda). The magistrates had sent a letter to the king asking him to declare where he stood on this issue, a gesture that some deputies construed as undermining the National Assembly’s authority. Robespierre denounced the letter as “criminal.”8 The irascible and frequently drunk vicomte de Mirabeau (André-Boniface-Louis Riqueti, not to be confused with his more famous brother, Honoré-Gabriel Riqueti, comte de Mirabeau) insisted that Robespierre was skewing the matter by ignoring key documents concerning the Parlement’s communication with the king. The vicomte then belched forth speech “peu mesuré,” too offensive, in any case, to be printed in the Archives parlementaires.9 A moment of disorder followed, after which demands were made to have the vicomte expelled from the Assembly for eight days. Barnave pointed out that the Assembly did not have the right to do so, since it had not yet passed a law for dealing with such violations, and the matter was soon dropped.

Another deputy was nearly expelled on January 22, 1790. The matter concerned an insult. During heated discussion about the management of state finances, Jean-Siffrein, abbé Maury blurted out, “I insist that those in this Assembly whom nature has denied all but a shameful courage.”10 This was considered an egregious affront. Indignant, one deputy proposed expelling Maury from the Assembly and having his constituents in Péronne elect another representative. He claimed that, although public opinion was capable of redressing insults against individuals, those against the National Assembly required official, punitive measures, since they amounted to an attack on the representative body in which the nation had invested its honor. If the Assembly failed to command respect and avenge itself, insults would eventually undermine efforts to enforce its decrees.11

The comte de Mirabeau agreed that some kind of official reprimand was needed but proposed a more moderate response. He called for censuring Maury. Maury claimed that according to new judicial maxims concerning the separation of powers, the National Assembly could not be both plaintiff and judge. Pierre-Louis Roederer countered by invoking the example of the French sovereign courts, the parlements. In cases of internal wrongdoing, the magistrates had legitimate authority to investigate and adjudicate. Roederer believed this logic should apply to the Assembly, warning that without the authority to enforce internal discipline, nothing would prevent deputies from disrupting meetings. In the end, the Assembly chose to follow the moderate guidelines it had set the previous summer. Mirabeau’s motion was accepted. Maury received formal censure, and his behavior was recorded in a procès-verbal.

The first instance of an exclusion for speech in the Constituent Assembly occurred on April 27, 1790. On the surface, the affair involved the violation of an oath. At root, it turned on the more profound issues of a national religion, religious freedom, and sectarian strife. On that morning, the Assembly elected the comte de Virieu for its president. Virieu’s election was controversial because of his recent protest against the decree of April 13, which put an end to right-wing efforts to declare Catholicism the national cult.12 Ever since August 1789, the right had sought to secure official exclusive status for their faith. Their aim was, in part, to gain political leverage in order to reduce the impending damage to their interests caused by the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (which declared the freedom of religious opinions) and the abolition of privilege (which put the fate of tax-free Church property into question). Although these reforms had been ratified in 1789, deputies had not yet agreed on how to implement them. When the right was defeated on April 13, Virieu, along with more than three hundred other deputies—that is, between a quarter and a third of the National Assembly—signed a petition protesting the decree. Published a week later under the title Déclaration d’une partie de l’Assemblée nationale sur le décret rendu le 13 avril 1790 concernant la religion, it circulated widely, galvanizing resistance to the Revolution and provoking unrest and massacres.

Efforts to oust Virieu from his post as president of the National Assembly began the morning of his induction on April 27. The Jacobin deputy Charles-François Bouche proposed a motion requiring incoming presidents to repeat the civil oath of February 4, 1790—the day when the National Assembly and the king formally declared their allegiances to the nation, the law, and each other. But Bouche added a clause requiring them to swear that they had never partaken and would never partake in any protest or declaration that undermined the Assembly’s decrees sanctioned by the king or that undermined the respect due to the king or Assembly.13 The measure, which passed, was clearly intended to challenge Virieu’s election.14

During his induction, Virieu made no mention of his participation in the protest declaration, but the left pressed the issue. “Who would have thought,” asked Alexandre de Lameth, “that the Assembly would choose for its president a member who protested its own laws?”15 Virieu replied that, since the king had not yet ratified the April 13 decree, his signing of the protest declaration did not constitute a violation of the civil oath.16 Bouche intervened to remind him that the oath had two components. The first forbade deputies from protesting decrees sanctioned by the king. This was the clause that Virieu’s defense was riding on. The second forbade dissent that weakened or undermined the honor of the king and National Assembly. He insisted that Virieu was guilty on this count.17 Charles de Lameth added that, even though Louis had not signed the April 13 decree at the time the Declaration appeared, Virieu’s involvement was all the more criminal, since it constituted an attempt to coerce the king through the threat of sectarian strife.18 For Bouche and the Lameth brothers, then, free speech ended where disrespect for authority and threats to public order began. The strongest argument in defense of Virieu was advanced by the abbé Maury, who claimed (rightly) that the inviolability of deputies, declared in the summer of 1789, prohibited anyone except a judge appointed by the National Assembly from ruling on the matter and only after proper investigation.19 The left, however, persisted, and eventually Virieu’s defenders backed down. Virieu resigned from his position as president.20

If one considers only what transpired in the Assembly that day, it would seem that the use of the oath to force Virieu to step down as president was an early sign of the inherent intolerance of Jacobins and their obsession with unity; and, indeed, the key left-wing deputies in this affair were members of the Jacobin Club. This interpretation would reinforce the view of revolutionary oath taking as nothing but coercion masquerading as unanimity, the acting out of Rousseau’s social contract, with all its illiberal trappings.21 Yet, we can better appreciate revolutionary oath taking, I believe, by considering its long-standing place in early modern political culture and the contingent problem of distrust provoked by conditions of regime change. Revolutionary oath taking owed much to Old Regime preoccupations with honor, deference, and allegiance. For centuries, oaths were an important part of corporate and political life.22 In France, high-ranking office holders came to Versailles to place their hands between those of the king to swear their allegiance to him. In the oaths sworn during coronations, kings promised to uphold the Catholic faith, peace, and justice in the kingdom. They also swore to enforce edicts against dueling—an oath that reveals much about the relationship between oath taking and concerns about violence.23 Although oaths were commonly sworn throughout France, they were prominent in frontier regions, where conflicting allegiances could readily spark wars.24 They were also commonly sworn in Enlightenment institutions, such as royal academies.25

Ironically, Edmund Burke—no friend of the French Revolution—was sensitive to the importance of trust and allegiance, which oaths were intended to reinforce. Instead of applying his insights to Revolutionary oath taking, he applied them to idealize feudal fealty, which he claimed the Revolution had destroyed. “By freeing kings from fear,” he wrote in Reflections on the Revolution in France, “fealty [declared through oaths] . . . freed both kings and subjects from the precautions of tyranny.”26 By “precautions of tyranny,” Burke was referring to preemptive violence, such as assassinations or invasions, which grew out of conditions of distrust. Burke failed to see that revolutionary oath taking was also intended to prevent “precautions of tyranny” by cultivating a climate of trust. So, too, have historians who have portrayed revolutionary oath taking as nothing but the imposition of Enlightenment ideology—the sign of sterile, authoritarian politics.27

The oath that brought down Virieu’s presidency on April 27 was a modified version of the civil oath of February 4, 1790. The events that led to this oath reveal much about the problems of distrust and violence in a period of abrupt political change. Some historians have argued that revolutionary oaths sought to replace the charisma of the king with that of the nation.28 Yet, the oath of February 4, which served as the basis for all major revolutionary oaths for the next two and a half years, was initiated by the king himself. It was intended not to eclipse his charisma but to fuse it with the honor and charisma of the nation. Louis swore the oath in a desperate effort to reverse a rapidly deteriorating political situation. At the beginning of 1790, suspicions about where he stood with regard to the Revolution were pushing France to the brink of civil war. In early January, the king’s brother presented himself to municipal authorities in Paris to deny rumors of his complicity in a recently unveiled counterrevolutionary plot to take the king abroad.29 Days later, violence broke out on the Champs-Elysées between royalist and radical groups within the Paris National Guard. Violence nearly erupted in the Cordeliers district of Paris on January 22 when police came through with an arrest warrant for the radical journalist Jean-Paul Marat (district fury forced the police to withdraw empty-handed). All this, together with reports of rioting in Brittany, Bas-Limousin, and Quercy, convinced the king’s advisors, notably Necker and Lafayette, that to stop ongoing entropy, Louis had to position himself publicly with regard to the Revolution.30 A royal oath sworn before, and to, the National Assembly was devised as a solution.

In his speech before the National Assembly on February 4, the king described, quite accurately, how “the suspension or inactivity of Justice, the dissatisfactions and hatreds that spring from persistent dissensions . . . combined with a general atmosphere of unrest” were “fueling the anxieties of loyal friends of the Kingdom.” To overcome these problems, he swore to “defend and maintain constitutional liberty, the principles of which the general desire [vœu général]—at one with my own—has consecrated.”31 Later that day, Marie-Antoinette, descending from the royal carriage with the dauphin, swore before the crowds gathered near the Tuileries Palace that she would raise her son to be loyal to public liberty and the laws of the nation. Inspired by the queen’s pronouncements and still under the spell of the king’s visit, deputies in the National Assembly devised an oath of their own, requiring it of all members: “I promise to be faithful to the Nation, the Law, and the King, and to maintain with all my power the Constitution decreed by the National Assembly and accepted by the King.”32

The oath spread quickly throughout France. In Paris, special masses were celebrated to honor it, municipal officials swore it, and zealous individuals forced random pedestrians to repeat it.33 In the provinces, it was received with equal enthusiasm, accompanied by Te Deums (Catholic hymns) and echoed in the correspondence of local officials to the National Assembly in the following weeks and months. In a world in which justice, administration, and the military were in disarray or mired in conflict, the oath offered hope and reassurance that, with some goodwill, strife could be averted.

But strife was not averted. Within three months, sectarian violence broke out in southern France, fueled in part by intransigent deputies who insisted that their allegiance to God trumped their allegiance to the nation, or that the nation was inseparable from allegiance to a Catholic God. When the left succeeded in blocking the motion to declare Catholicism the national religion on April 13, hundreds of deputies, in a powerful display of defiance, stood up in the Assembly, raised their right hands to the heavens, and swore an oath to God and their religion.34 The gesture posed the threat of schism—and schism over the issue of religion would unfold in coming months.

A week later, on April 19—the day the National Assembly transferred the administration of Church property to the state—dissenting deputies published their protest declaration, sending it into the provinces, somehow with the Assembly’s official seal. The declaration hit a France that was already on the brink of revolt in many places. Not only had fighting among French troops broken out in the North; contest over religion was also heating up in many areas, especially in the Midi.35 Despite numerous studies on the violence of 1790, most general accounts of the Revolution still ignore or gloss over these incidents, reinforcing the myth of 1790 as the “happy” or “peaceful” year of the Revolution.36 Yet, the signers of the declaration were neither happy nor naive about the impact their declaration would have.37 Upon exiting the Assembly on April 12, the abbé Maury was reported announcing that the issue of a national religion had lit the fuse of a political “powder keg.”38 To prevent troubles in Paris, the National Guard was stationed in sensitive locations on the morning of April 13. Aside from minor incidents (angry crowds chased two right-wing deputies through the streets of Paris after one of them had drawn his sword), peace was maintained.39

In the Midi, however, the powder keg exploded. The worst incidents occurred in Nîmes, where Protestants, who dominated the National Guard, and Catholics, who controlled the municipal government, clashed. On April 20, 1790—too soon to have received the April 19 Déclaration but certainly late enough to have been informed about the scandal in the Assembly on April 13—reactionary Catholics in Nîmes published a pamphlet insisting that Catholicism be declared the official religion of the nation. Less than two weeks later, on May 2–3, violence broke out. The National Assembly was sufficiently alarmed to summon the Mayor of Nîmes, Jean-Antoine Teissier, baron de Marguerittes, who was also a national deputy, to explain his actions, or rather, his suspicious inaction the day Catholics initiated hostilities against Protestants.40 Marguerittes had been on leave from the National Assembly and was in Nîmes at the time violence erupted. On behalf of outraged deputies, Charles de Lameth tried (but failed) to persuade his colleagues to suspend the inviolability of deputies in order to hold Marguerittes responsible for the violence.41

The situation in Nîmes worsened. On June 1, Catholic forces published another provocative pamphlet in which they openly aligned themselves with religious opposition to the Revolution in Alsace, Comminges, Toulouse, Montauban, Albis, Uzès, Lautrec, Alais, Châlons-sur-Marne, and numerous other towns.42 They claimed that although they had been among the first to denounce the abuses of the Old Regime in 1789, they now wanted to bring the Revolution to an end. They professed their allegiance to monarchical and religious authority, which they believed the Revolution was undermining. Oddly, they justified their resistance to the Revolution by invoking the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, which guaranteed the freedom of religious opinions provided public order was not disturbed. To charges that they themselves were disrupting public order, they responded, “People cannot accuse us of expressing opinions that disturb the public order since our mission is, to the contrary, to reestablish and maintain it.”43 For them, as for many devout contemporaries, “public order” meant not merely the absence of agitation; it referred to a moral order as well, one based on throne and altar. In any case, their intransigence provoked another outbreak of sectarian violence between June 14 and 17, killing more than three hundred.44

Throughout the spring and summer of 1790, the National Assembly received a steady stream of denunciations of the declaration of April and the flurry of local pamphlets inspired by it. The municipalities of Arras, Bordeaux, Castelnaudary, Châteauneuf, La Rochelle, Lyon, Lorient, Montbrison, Issoudun, and Tarbes, among others, expressed their indignation and alarm. They warned the Assembly about the destabilizing impact of these tracts, which they were banning and seizing as best they could.45 Some threatened to prosecute anyone involved in spreading them.46 Officials in Issoudun and Saint-Martin-en-Ré went so far as to order the public executioner to burn copies of them in front of their respective city halls.47 Members of the conseil général of the commune of Lyon explained why they thought the protest declaration, which they banned, was treasonous.

FIGURE 6.1. Massacre des patriotes de Montauban. Courtesy of the Carnavalet Museum. Unlike in Nîmes, where hundreds died in sectarian violence, few were actually killed in Montauban.

Such protests, which might have been considered simply erroneous had they not been publicized, become crimes of lèse-nation the moment that they are published and distributed with the National Assembly’s [official] seal to ecclesiastic and religious bodies in order to . . . renew the flames of religious strife.48

The council reiterated the oath of February 4 and declared its determination to bring charges of lèse-nation against anyone involved in undermining the Assembly’s decrees or threatening public order.

By summer 1790, even supporters of the protest declaration began acknowledging the dangers of ongoing resistance. In his pamphlet published in July, the deputy François Simonnet, abbé de Coulmiers encouraged supporters of the declaration to desist. He said that, even though he believed Catholicism should be the national religion, public opinion was clearly opposed and ongoing intransigence was threatening public peace.49 He went so far as to characterize ongoing support for the protest declaration as “criminal.”50

On July 12, 1790, the National Assembly passed the Civil Constitution of the Clergy. This far-reaching reform nationalized Church property, put priests on the state payroll, made clerical posts subject to local elections, restructured dioceses and parishes around new civil jurisdictions, and required new clergymen to swear an oath based on the civil oath of February 4 (with minor additions). In November, the National Assembly went further, imposing the oath on all clergymen and teachers, threatening to remove them from their offices if they refused. Many historians have criticized the clerical oath of November for being unnecessary, illiberal, and catastrophic for the course of the Revolution. It has been described as “one of the Constituent Assembly’s greatest mistakes,” producing a crisis of conscience by forcing individuals to choose between their religion and the Revolution.51

There is no doubt about the oath’s polarizing impact, which has been thoroughly documented.52 Still, I would stress the significance of struggles over defining the place of religion in the new order even before the Civil Oath was imposed on the clergy. Catholic resistance to religious freedom was indeed threatening the new order, as the sectarian violence of May and June 1790 demonstrates. In their Exposition des principes sur la Constitution civile du clergé of October 1790, right-wing bishops in the National Assembly announced their refusal to recognize the Assembly’s policies on religion until receiving the pope’s views.53 They explicitly rejected the freedom of religion, claiming that “when legislators protected the freedom of religious opinions [in the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen], it never entered their minds to allow all religions to be free, except for one, the religion that has been the national religion for more than twelve hundred years.”54 Historians critical of the clerical oath often mistake the distinction contemporaries made between spiritual and secular domains with the more recent distinction between the public and the private. In most developed democracies, religious freedom is based on the premise that religious convictions have no privileged place in public affairs and cannot serve as criteria for the negotiation or judicial settlement of competing interests. Catholic reactionaries during the Revolution, however, insisted on the distinction between secular and spiritual authority, both of which were public in their minds. They had no intention of seeing religious faith relegated to the private sphere. To the contrary, they wanted Catholicism to be declared the official national cult—the moral essence of “public order,” which would justify limiting free expression according to the Declaration of Rights. In light of the clergy’s agenda, the clerical oath should be seen not as gratuitous provocation by Jacobins unable to distinguish between public and private spheres, but rather as an attempt to prevent sectarianism from undermining the Revolution’s achievements, religious freedom among them. Seen in this light, the clerical civil oaths decreed in July and November 1790, like the rapid rise of Jacobin Clubs throughout France in the spring of 1790, were not so much the cause of religious troubles but responses to Catholic resistance to the Revolution.55 Given the Church’s privileged role in education—there was no universal secular education system yet—the insistence of revolutionaries that the clergy swear allegiance to the new order can be seen as an expression of practical concerns.

If oaths were intended to prevent conflict, honor was invoked to structure conflict that was not averted. Honor, which had figured prominently in social and political life during the Old Regime, persisted into the Revolution, becoming imbricated in profound sociopolitical shifts. In his Honour among Men and Nations, Geoffrey Best notes that the Revolution marked a decisive turning point in the history of honor.56 Whereas honor had been based on social hierarchy before 1789, the Revolution democratized it while also fastening it to the sacred concept of the nation. How did this transformation take place? Best attributes it to the rise of Jacobins to power in 1792 and their commitment to Rousseauian notions about virtue and unity within the nation-state. This explanation, I believe, reifies Jacobin ideology and exaggerates its causal role in the radicalization of the Revolution. Like many discursive analyses of the French Revolution, it takes the Jacobin discourse of 1792–1794 as its starting point, confusing effects for causes. It fails to appreciate the way in which honor had already started becoming collectivized in the nation before the Revolution and overlooks how Jacobin discourse itself grew out of interactions between elite politics and popular agitation—interactions inflected by a deeply engrained culture of honor.

During the Old Regime, however, popular and elite cultures of honor were distinct, and elite violence rarely fused with popular revolt. Social and political hierarchy determined legitimate forms of resolving conflicts over honor. With the advent of civil equality in 1789, the system of honor, esteem, and deference was thrown into question. The dignity that had been concentrated in elites, giving them social and juridical privileges, was now recognized to exist among the people. Although revolutionaries did try to maintain hierarchical distinctions, notably, between active and passive citizens (defined by property) and between men and women, the genie was out of the bottle. With the democratization of honor, popular indignation and punitive demands gained legitimacy. Recognizing this, leaders of the left and the right often exploited them to advance their respective causes.

The first arrest for speech of a deputy in the National Assembly occurred on August 21, 1790. The incident reveals how elite and popular cultures of violence merged in struggles over honor. That morning, the deputy Thomas-Louis-César Lambert de Frondeville distributed a pamphlet he had written to deputies arriving in the Assembly. In it he boasted about the censure he had received a few days earlier in the Assembly for his behavior during discussion of a political affair dating back to 1789. Frondeville’s insolence incensed deputies, who declared his pamphlet a punishable insult to the National Assembly. The question was how far to go with the punishment.57 Debate was heated. Some left-wing deputies declared that the majesty of the nation resided in the national representation; any insult against the Assembly, therefore, amounted to an insult against the entire nation.58 Maury countered with the argument that there was no law justifying the arrest of a deputy for speech (which was correct). He claimed that perceptions of honor or dishonor belonged to the realm of public opinion, and that it was not for the deputies to decide whether the Assembly’s honor had been violated. Invoking Old Regime custom, the left retorted that all corporate assemblies had the right to exercise internal policing and discipline members. But the right insisted that punishment be based on laws, not custom. If the Assembly punished without recourse to a previously declared law, they would be, in the bigoted words of a clerical deputy from Noyon, “worse than the Jews.”59

The situation became explosive when Barnave declared that if a deputy congratulated himself for the censure he received from the Assembly, then imprisonment was the least severe penalty he should expect.60 This statement implicitly invoked and legitimized punitive violence. The right struck back immediately in the words of Louis-Charles-Amédée, comte de Faucigny-Lucinge, who leapt forward and cried out, “This is all starting to look like an open war by the majority against the minority. There’s only one way to settle this . . . to attack those bastards with sabers in hand.”61 Deputies on the left rose, bracing themselves for combat. Frondeville, panicking, rushed to the podium to try to restore calm. He pleaded guilty and begged the Assembly to punish him, but only him, not Faucigny. (Faucigny, by the way, had been a career cavalryman in the Old Regime.) Frondeville claimed that if, for his defense, a deputy would go so far as to jeopardize the security of the Assembly and declare civil war, then all responsibility should fall on him, and he encouraged the Assembly to overlook Faucigny’s call to arms.62 The Assembly granted the first part of Frondeville’s request, condemning him to eight-day house arrest.63 The remaining problem was what to do with Faucigny. For some deputies, a call to arms was far more egregious than Frondeville’s puerile pamphlet. But Guillaume-François-Charles Goupil-Préfelne, who had initiated debate on punishing Frondeville, urged his colleagues to “close [their] eyes” to this incident. Like Roman legislators who believed that parricide was too horrible a crime to even mention, they should pass over the event in silence.

This “oblivion” option was promptly extinguished when a rumor spread throughout the Assembly that the comte de Mirabeau had ordered messengers to inform crowds outside about what had just happened. Mirabeau dismissed the rumor, but he nevertheless admitted that the left had so many supporters, its popularity might turn out to be its greatest weakness if it proved incapable of securing the personal safety of Frondeville and Faucigny.64 Faucigny must have recognized these risks, for he immediately apologized and declared himself willing to submit to whatever punishment the Assembly wished to impose.65 The left was reluctant to make a martyr of him and sought ways to downplay the event. The two sides compromised: after formally condemning Faucigny, the Assembly accepted the errant deputy’s apologies and pardoned him.66 In this way, the National Assembly avoided losing face and, in obtaining an apology, assuaged popular punitive sentiments that might have boiled over had Faucigny remained intransigent or gone unpunished.

We return to the incident concerning the tricolor ensign in October 1790. The issue had grown out of concerns in Paris about insurrections in Brest, where sailors in the French Navy, recently arrived from Saint-Domingue, had staged a mutiny against their officers. The municipality and the local Jacobin Club got involved, and the situation deteriorated.67 Between mid-September and mid-October, Brest was in a state of rebellion, no insignificant matter given its vulnerability to British invasion. France was still traumatized by a similar such mutiny in Nancy, which led to a bloodbath that, according to one historian, killed as many as three thousand people.68 Left-wing deputies suspected Louis’s ministers of fomenting reaction in Saint-Domingue (the governor had tried to shut down the new local representative assembly). The mutiny in Brest, they claimed, was nothing but the predictable backlash of the sailors against their reactionary officers. In a controversial motion proposing that the ministers be held responsible for the troubles in Saint-Domingue and elsewhere, left-wing deputies included an article calling for the replacement of the traditional white Bourbon Banner with the revolutionary tricolor ensign.

The rebellion in Brest, along with the smoldering sentiments over the massacre in Nancy, should be kept in mind in assessing Mirabeau’s long, incendiary speech. In it, he maintained that symbols were powerful instruments in the hands of patriots and counterrevolutionaries alike and should not be treated superficially.69 The Brest tragedy, he insisted, demonstrated this. His repeated reference to the white flag as the symbol of counterrevolution infuriated the right. The situation became explosive when he stated that a deputy defending the white flag would have paid for such views with his head had he voiced them just a few weeks earlier.70 The statement was a thinly veiled threat, and it enraged the right. In the commotion that followed, Guilhermy was overheard calling Mirabeau a “scoundrel” and “assassin.” Guilhermy defended himself, insisting that Mirabeau had insulted deputies by interpreting support for maintaining the white flag as counterrevolutionary.71 He added that Mirabeau’s statements incited sedition by legitimizing popular punitive violence against deputies who supported the Bourbon Banner.

Indeed, the presence of crowds outside the National Assembly could not be ignored. Terrified that he might be implicated in this affair, Maury requested that two officers be sent out into the Tuileries gardens to inform the crowds that he had nothing to do with this incident.72 A fellow right-wing colleague, Jacques-Antoine-Marie de Cazalès, frowned upon Maury’s request, warning that nothing was more dangerous than putting the National Assembly in direct contact with the people.73 Cazalès added that he had indeed found Mirabeau’s speech to be libelous but claimed to have refrained from stopping Mirabeau out of respect for the freedom of expression. This same freedom, he now insisted, should be extended to Guilhermy, even if the Assembly might consider calling Guilhermy to order, as was purportedly done in the British Parliament.74

After more wrangling, Roederer boiled the matter down to this: was it tolerable that a deputy call another a scoundrel and assassin?75 At this point, Mirabeau turned the dispute into a zero-sum duel: “I demand that the Assembly condemn either Mr. Guilhermy or myself. If he is innocent, I am guilty.”76 The majority chose the former option and condemned Guilhermy to three-day house arrest.77

In an open letter to his constituents, Guilhermy described the maneuvers against him in the Assembly that day.78 He claimed that Mirabeau’s allies had tossed notes out the windows of the Assembly, informing crowds that he, Guilhermy, had insulted Mirabeau, thus inciting them to avenge the comte. He provided the names of several witnesses (and claimed he could provide thirty more) who had seen individuals scooping up the messages and reading them aloud. He complained that when he and several other deputies tried to alert the Assembly to this dangerous situation, the majority brushed off the matter, claiming that the notes belonged to a journalist whose assistants were picking them up on the other side before carrying them to print shops.79 Whether the notes were intended for the crowds or the presses, the crowds were clearly being informed (or misinformed) about events going on inside as they unfolded. Maury’s panicky request to have officers inform the crowds outside that he had nothing to do with the incident suggests that such communication had occurred and, more significantly, that threats of popular violence were inflecting internal Assembly politics. It is likely that Mirabeau’s allies exploited popular punitive sentiments to intimidate the right. In any case, the tactic succeeded in avenging Mirabeau for insults in the absence of legal limits on speech offenses. In the long run, however, such demagogical tactics had dangerous implications. They encouraged conflating the individual honor of deputies with the honor of the nation. They reinforced the idea that popular punitive violence—or the threat of it—might be just.

Revolutionaries did no better than their predecessors in curtailing the age-old practice of dueling. Demands that the National Assembly pass strict laws against it were made frequently after 1789, but the odds of eliminating the practice were not great when deputies themselves did not refrain from engaging in it.80 The duel between Charles de Lameth and Armand-Charles-Augustin de la Croix, duc de Castries, which occurred in November 1790, just a few weeks after Guilhermy’s arrest, reveals how personal rivalries could escalate into affairs of state, stirring up Parisian crowds and leading to imprisonment for injurious speech.

The events leading up to the duel began when the vicomte de Chauvigny arrived at the Assembly (escorted by guards) seeking to settle a private matter with Lameth. When Chauvigny challenged Lameth to a duel, Lameth sneered, saying that the duc de Castries must have put him up to it. When news of this remark reached Castries (he was absent from the Assembly that morning), he rushed to the Assembly to challenge Lameth to a duel. The next morning, the two deputies squared off on the Champs de Mars. Lameth, the expected victor, was wounded in the arm.81

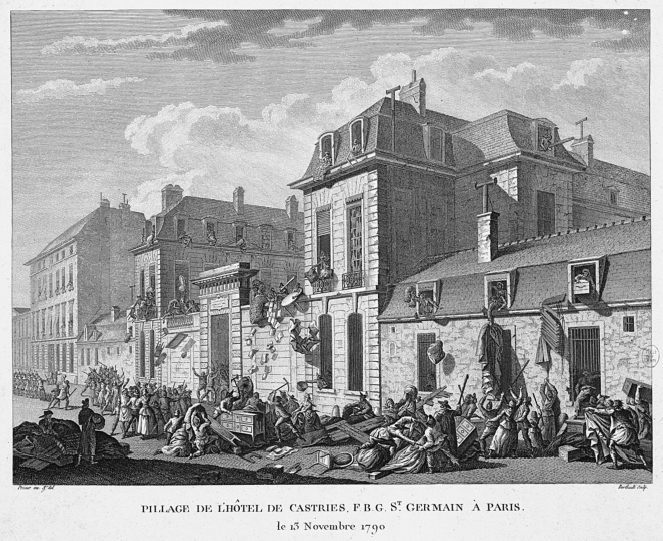

As deputies discussed the event in the National Assembly, crowds numbering between forty thousand and two hundred thousand (the latter figure was undoubtedly exaggerated) descended upon Castries’s hôtel particulier.82 Castries was already notorious for having protested the abolition of noble titles the previous summer and for having led cavalry troops in the suppression of the mutiny in Nancy. After storming the residence in search of him and discovering that he had fled, the invaders ransacked the place, tossing furniture out windows. Upon receiving news about the riot, some deputies applauded, but others scowled them into silence. Alarmed, Maury exhorted the National Assembly to order the municipality to deploy forces to break it up. He also demanded that all such gatherings be treated as lèse-nation and that all who participated in them be corporally punished. Another deputy called for outlawing duels but warned that, given the present “emotional state” of the deputies, it was not wise to convict Castries now.

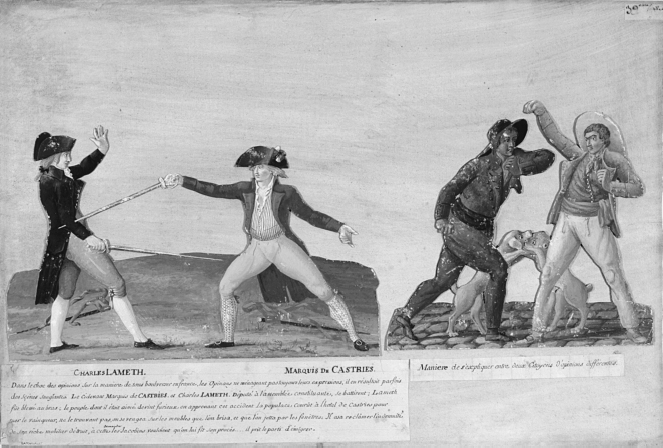

FIGURE 6.2. Duel Lameth-Castries, Bagarre d’hommes du peuple. Courtesy of the Carnvalet Museum. The caption on the left reads, “In the clash of opinions over how to disrupt everything in France, those with opinions are not always in control of their expression. Bloody situations sometimes result.” The duel and its tumultuous aftermath are described. The caption on the right reads, “The manner in which ordinary citizens explain their different opinions.”

That evening, a deputation of National Guardsmen from the section Bonnes-Nouvelles arrived in the National Assembly. The guardsmen demanded that Castries be charged with lèse-nation.

Considering that nothing is more urgent than to impose public vengeance against those who attack the respect due to the nation’s legislators and considering, moreover, that any further indulgence might embolden the enemies of the Revolution and slow down progress on [drafting] the Constitution, [the battalion of Bonnes-Nouvelles] sends its envoys to the Assembly to request, with all due justice, a decree declaring attempts to provoke a national deputy to a duel or to hinder him from carrying out official duties to be a crime worthy of universal indignation and treated as lèse-nation.83

The demand met with vigorous applause in the Assembly. On the right, however, a deputy from Angoulême, Antoine-Joseph Roy, chided enthusiastic deputies, saying, “Only villains could applaud such a request.”84 Indignant murmurs spread on the floor, and once again demands for punishment were made. This time the left would not settle for house arrest. They wanted Roy imprisoned.

FIGURE 6.3. Pillage de l’hôtel Castries. Courtesy of the Carnavalet Museum.

At this point, the National Assembly had two matters to settle: duels and insults. Barnave drew a causal link between the two, arguing that insults often sparked acts of vengeance and public disorder. “If there is a true means to prevent personal vengeance and to take out of the people’s hands the arms they use to attack their fellow citizens, it is to empower the law to stop them. . . . [The Assembly should] punish insults, and soon people will stop making them.”85 He asked his fellow deputies, who among them had not, at one time or another, been insulted just walking through the Tuileries? An ironic voice, probably from the right, shot back that they had even been insulted from the podium.

Barnave then peppered his injunctions with suspicions about plots. He claimed that counterrevolutionaries were testing the limits of the people’s patience by provoking them to violence. Castries’s aggression offered Barnave an opportunity to stretch a particular instance of personal animosity into an orchestrated conspiracy.

I am not sure of the exact source of such provocations, but there is clearly a system of provocation directed against good citizens. It seems that conspirators are seeking to exhaust the people’s steadfastness which has been, up to this point, the source of terror and despair for the country’s enemies.86

Since Barnave was a leading Jacobin, such speech seems to bear out François Furet’s observations that Jacobins were prone to paranoia. Yet, the right harbored similar such suspicions. Roy insinuated that some external and malicious force (on the left) was behind this uprising: “Whether the people acted on their own initiative or whether they were provoked by . . .” The left growled, but Roy persisted. “It seems my hypothesis raises complaints; but who here has not remarked that the enemies of public order have always incited the people to seditious acts, that there has not been a single insurrection in the realm which has not been generated by the enemies of the public good.”87

After both sides vented their suspicions about plots, Virieu spoke up. He said that it was dangerous to allow the Assembly to be transformed into a Roman arena, “where the moderate clash of opinions gives way to the violent clash of passions.”88 To calm tensions in the National Assembly, he thought it was necessary to ban all approbatory and disapprobatory expression by the audience—an audience, by the way, that was filled with bribed supporters of the left, at least according to the secret correspondence of Mirabeau.89 The left howled and hissed, but Virieu persisted, deploring “in the name of the provinces” the injustice of a few hundred spectators imposing their views on the entire nation.

Further altercations followed. On the right, Louis, marquis de Foucauld de Lardimalie opposed Roy’s arrest on the basis of the inviolability of deputies.90 The comte de Mirabeau (who had been the driving force behind the decree securing the inviolability of deputies in June 1789) countered with biting sarcasm, humiliating Foucauld and stirring up such indignation that deputies had to be physically restrained from assaulting him. It appeared now that the left was as prone to incendiary propos as the right. Mirabeau was, in fact, called to order by the president of the National Assembly, but the left kept pressing for Roy’s arrest. Barnave emphasized the exigencies of the moment. “I request that, given the circumstances and the dangerous effects of indulgence, the National Assembly arrest [Roy].”91 Mirabeau stretched Barnave’s contingent imperative into universal principle. Much like the leaders of the Committee of Public Safety in the winter of 1793–1794, he warned that “continued indulgence will be criminal and fatal. . . . La chose publique [the common, sovereign weal] is in danger. . . . You need to impose obedience to legitimate authority throughout the Empire.”92 He continued his tirade by flattering the crowds who had ransacked Castries’s residence.

Behold, the people: violent but reasonable, excessive but generous; behold, the people even in insurrection: [this is how they act] when a free Constitution has restored in them their natural dignity and they feel this freedom threatened! Those who would judge the people otherwise underestimate and insult it.93

These paradoxical pairings reveal the strains involved in trying to exploit and sanitize popular violence. Mirabeau described how “dispassionately” these crowds imposed their vengeance, “destroying [Castries’s] house with a kind of order and calm.” Those exiting it, he claimed, emptied their pockets so that “no baseness would sully the vengeance they believed to be just.”94 (He said nothing about how things got into their pockets in the first place.) The image of a virtuously restrained but punitive crowd pandered to the rioters as well as to elites who expected legitimate political actors to behave with civility and restraint, their own inability to do so notwithstanding. Mirabeau ended his speech by imploring the deputies to “make an example of how your respect for the law is neither tepid nor feigned . . . decree that Roy be condemned to prison.”95 His performance must have been spellbinding, for no one refuted him with the fact that no law authorized such arrest.

Discussion then turned to the question of punishment. Various propositions were advanced, ranging from three-day house arrest to eight days in prison. Pierre-Victor Malouet made one last-ditch effort for the right, pushing Barnave’s reasoning to its logical conclusion by proposing that, if the National Assembly was going to arrest Roy, it might as well arrest all who insulted deputies in the Palais-Royal, in the Tuileries gardens, and even from the audience of the Assembly.96 Another deputy on the right, less sarcastic, tried to have Roy’s punishment mitigated by citing the Latin proverb Prima gratis, secunda debet, tertia solvet, claiming that this was only the second violation of its kind and therefore punishment should be light. The left corrected the count, pointing out that it was the third such incident, following the condemnations of Faucigny and Guilhermy. Roy’s offense thus had to be paid in full (solvet).97

In the end, the majority passed a decree condemning Roy to three days in the Abbaye prison. To avoid provoking further trouble, deputies did not have Roy arrested on the floor, allowing him to present himself at the prison within the following twenty-four hours. Interestingly (and tellingly), now that Roy was free to exit the Assembly on his own, he adopted an apologetic and submissive tone, promising to uphold the Assembly’s decision with utmost respect and adding that he was willing to serve as long a sentence as the Assembly wished to impose.98

Were these punitive exclusions of 1790 in the Constituent Assembly the beginning of an inexorable slide into the Terror? I think not. First, it appears that no such arrests took place in 1791, despite a close call in January. An arrest did occur in 1792. The deputy Jean-Jacques-Louis Calvet-Méric was thrown into the Abbaye prison for “insulting the French people in the person of one of its representatives.”99 This appears to be an isolated case. Second, although nearly all the excluded deputies of 1790 would emigrate and become active counterrevolutionaries after December 1791 (Virieu, Frondeville, Faucigny, Guilhermy, and Castries), they do not seem to have been so vexed or traumatized by their treatment in 1790 as to flee France as soon as they might have—there was a major wave of emigration in December 1790. They continued participating in Assembly politics for nearly another year before going abroad. Their temporary arrests (or, in the case of Virieu, forced resignation) were not that shocking, since corporate bodies had habitually exercised such disciplinary authority over members.

That said, these exclusions shed light on the cultural dynamics that injected punitive impulses into revolutionary politics. They reveal how oaths, honor, and religion became polarizing forces after 1789. Under stable conditions, the act of oath taking can reinforce allegiances, express the central values of the political order, and strengthen attachments to that order. Indeed, oaths continue to hold an important place in republican political culture today. Under revolutionary conditions, however, oaths served as vehicles for asserting competing notions about the sacred, prelegal foundations of authority. While progressives elevated the nation and sought to place the sacredness of the monarchy and religion within its scope, reactionaries elevated throne and altar over the nation and new civil authorities. In the clash over first principles, politics took on eschatological dimensions, making moderate, middle paths increasingly treacherous. With such inflated stakes, compromise smelled of conspiracy, and opposition took on the hue of heresy or treason.

Revolutionary conditions also radicalized the culture of honor. With the collapse of Old Regime hierarchy, honor became horizontally reconfigured. Elite and popular forms of violence—the duel and rebellion—began fusing into a politically combustible mix. In the volatile economy of coercion and punishment being worked out between authorities and agitating forces, the nation’s honor was increasingly invoked. To be sure, Rousseauian conceptions of collective sovereignty were often invoked as well. Ultimately, though, the drive from political representation in 1789 to popular sovereignty and terror in 1792 and 1793 was fueled by calumny, honor, and vengeance—the dynamics of a hierarchical culture unhinged in the throes of democratic transition.