24

Evil and good, they braided play Into one cord.…

MELVILLE, Clarel

Homer climbed into his car and drove to Kitty’s, chewing over in his mind the tasty bits of news Fern had offered up on the sacrificial plate of his tin policeman’s badge. There was something deliciously tantalizing in the thought of the restless rovings of the two Greens, man and wife, during the twenty-four hours before Helen’s death. There was Joe, on the one hand, wandering around the island all night long with Kitty’s poem in his hand. And there was Helen, on the other, rushing from place to place the next morning, looking for something. Searching all over, trying to find it. Something or somebody. But what? Or whom? Joe had lost that piece of paper—could Helen have been looking for that? But why would she look for it in those three places? Joe hadn’t been anywhere near any of them. Or had he?

Homer found Kitty poking around the sloping ground in front of her house with a muddy book in her hand. Her knees and face were muddy. “Is this blueberry?” she said. “This thing here? Maybe it’s broom crowberry. I wish I weren’t so ignorant. I hate to keep bothering Alice.”

“Why don’t you ask Bob Fern?” said Homer. “He knows all that stuff. Besides, the poor fool is in love with you.”

Kitty put out her hand to catch a raindrop. “There, I knew it would begin soon.” She strode into the house in front of Homer, her head down. “I wish he wouldn’t get himself in trouble on my account. I don’t dare look at him. I feel like a basilisk. You know, that dragon that kills with one glance of its, horrible gruesome eye.”

“A basilisk.” Homer laughed. “Well, thank heaven I’m safe. To me you’re just a client who happens to have horrible gruesome eyes. Strictly business arrangement. Listen, basilisk, I met Mrs. Magee this morning.”

“No! What was she like?”

“Oh, she was all right. You just have to kind of wrench yourself around and see things from her point of view. When she stopped being refined I sort of liked her. Say, what do basilisks eat? Besides the corpses of their victims? Basil, naturally—har har. What have you got in your icebox a fellow could …”

“Well, I’ll take a look. Sit down.” Kitty took some hard-boiled eggs and a loaf of rye bread out of her refrigerator and began shelling the eggs. “I had a letter from my publisher this morning,” she said solemnly.

“Oh?”

“My book is doing very well.”

“Mmm. I suspect it is. For all the wrong reasons, I suppose.”

“They sent me a check. Biggest I ever got.” Kitty reached for an envelope on the windowsill. “Here it is. Take it. I don’t want it around anymore.”

“Oh, go on. Look, girl, we’ve been through this before. I’ve been well enough paid already. The money is coming out of my ears, for chrissake.”

“It is? Really? Good!” Kitty was surprised to learn that the Commonwealth of Massachusetts was so generously rewarding its charity lawyers. “You’re keeping track, aren’t you? We’ll have a grand accounting and setting to rights when—after it’s all over.”

“Oh, sure, sure. Now look. I have a job for you. How would you like to go to Mrs. Magee’s Property Owners Rights Association meeting tonight?”

“Me? Oh, Homer, last week she wouldn’t even show me a cottage. She won’t stand for any criminals at her meeting.”

“Well, then, I suppose I’ll have to go myself.” Homer picked up his sandwich, then put it down on his plate, a big smile on his face. “I know. I’ll wear my cloak of invisibility. Did I ever tell you about my cloak of invisibility? I mean, we’ve all got our little mythological devices. You’ve got a basilisk eye, I’ve got a cloak of invisibility.”

“I hope it’s an extremely large cloak. What are you anyway, Homer—seven feet tall?”

“No, no, nothing like that. Look, I’ll show you how the thing works.” Homer got up and ducked out of the kitchen. Kitty could hear him breathing in the parlor. Then he shambled in again, smiling vaguely in no particular direction, put out his hand at Kitty feebly, withdrew it before she could grasp it, said something that sounded like Gdeebmnnn, bumbled behind the backless chair into the corner of the room and let himself down clumsily onto the floor, where he sat hunched behind his enormous knees with his eyes half closed and his mouth drooping open. “How-ziss?” he said drowsily.

“Perfect,” said Kitty. “I can hardly see you. You’re sort of transparent.”

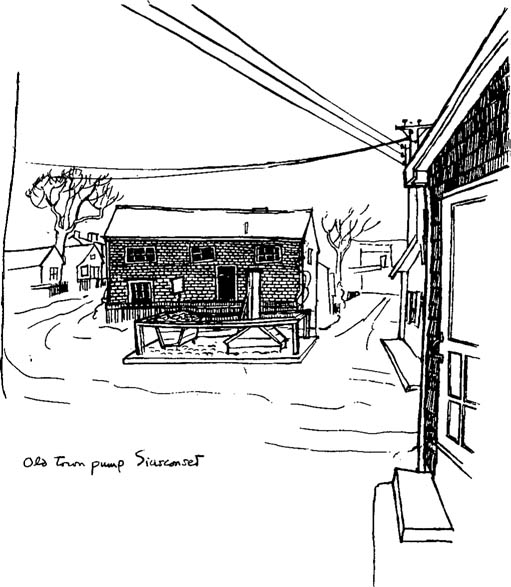

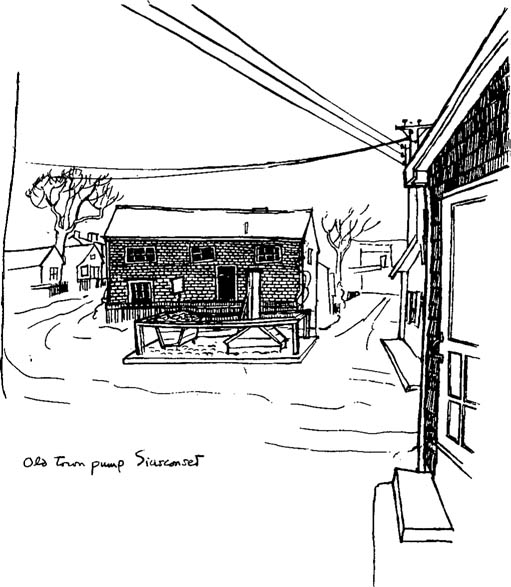

Homer’s cloak of invisibility worked surprisingly well. When he loomed up in the doorway of Mrs. Wilkinson’s big house on the North Bluff at Siasconset, his image registered clearly for only a moment or two on her sharply perceptive retina. Then his terrible posture and wretched articulation and the poverty of the air supply from his lungs and his general air of inconsequence and self-effacement had their effect, and Mrs. Wilkinson soon forgot him in the press of meeting other guests. Homer was able to shuffle into the living room and settle down on a four-legged stool behind a large chair in one corner and withdraw into anonymity, carefully avoiding the look of startled recognition on the face of Mrs. Magee, who was sitting beside the fireplace preparing to conduct the meeting. In a moment the last arrivals had come in, and the business of the evening got under way.

Mrs. Magee carried the ball. She began by reading a list of property owners who had already pledged their support to the cause of overturning the new bylaw. It was a long list. Homer amused himself by comparing Mrs. Magee with her hostess, Mrs. Wilkinson, who sat on the other side of the fireplace in a matching crewelwork chair—Mrs. Magee the businesswoman, the realtor, her spun-glass hair glinting against the dark wood of the paneled wall, her turquoise knitted outfit form-fitting, fabulous; Mrs. Wilkinson an old war-horse, her Fair Isle sweater dyed to match her heather-mixture skirt. They sat in the two handsome chairs like two queens of Nantucket. Evil queens, decided Homer, giving them their due. Representing no majesty but money, no ancient ancestral claim, no roots in the history of the island, no care or concern for its fragile grace. Here they were in the same place working for the same cause—but of course they were different women altogether. Mrs. Wilkinson could sit quietly in the arrogance of inherited and wedded wealth, gazing with insolent indifference at the motley lot in her living room, while Mrs. Magee had the quick nervous gestures of someone who had clawed her way up, who would never be at rest.

She had finished reading the list. She was introducing the man on her left. “With us this evening,” said Mrs. Magee, “is Mr. Hamilton Brine, an attorney who has tried many cases of this nature before the superior court. He will be representing Mr. Holworthy and me in the suit we have filed against the Town of Nantucket, declaring the recent act of the Town Meeting unconstitutional. But before we hear from Mr. Brine, why don’t we all introduce ourselves one at a time and state the nature of our objections to the bylaw? Mrs. Wilkinson, would you begin?”

Mrs. Wilkinson stirred in her chair and leaned forward, narrowing her old eyes as she sucked on her cigarette and coughed. “Before he passed away, my husband, Donald, bought sixty acres here in the neighborhood of ’Sconset because they were about to be picked up by a cheap developer. Donald thought a lot of nasty little houses would destroy the picturesque character of the village and lower the property values. So he bought the land himself as an investment, thinking he might divide it up into a few substantial estates someday. Now of course that investment has become worthless.” Mrs. Wilkinson leaned forward and stubbed out her cigarette with grim emphasis.

Mr. Holworthy was next. He was a freckle-faced sandy-haired fellow of mild address, who had, it turned out, a true reverence for the principles upon which his country had been founded. “It just seems to me that the new bylaw isn’t part of our democratic tradition here in the United States of America,” he said. “Like it says in the Declaration of Independence, all men are created equal—well, we’re not equal if some people can develop their property and some people can’t. It’s the principle of the thing that bothers me.” Homer, crouched obscurely in the corner, reminded himself that in addition to his anxiety about these noble abstractions, Mr. Holworthy might also be slightly concerned about the loss of his million dollars.

Harper J. Cresswell agreed with Mr. Holworthy. He too had lofty ideological differences of opinion with the Nantucket Protection Society. Again Homer had to supply for himself Mr. Cresswell’s strong interest, both financial and sexual, in Mrs. Magee and her various enterprises. Likewise with Samuel Flake-ley, whose sense of patriotism had apparently been deeply and profoundly shocked by this betrayal of the grand designs of the founding fathers of the nation.

The next speaker was a bony little woman in thick glasses and an unbecoming dress. “My name is Doris Pomeroy,” she said. “I’ve only got a very small piece of land, just outside of town. I’ve been going out there on Sundays, planting cedars and pine trees. I’ve been saving up for years to build myself a little place there. And now I can’t. I tell you I’m just heartbroken about it. I just hope there’s something we can do.”

Homer sat up straighter on his four-legged stool. The testimony had taken on a different character.

“I am Erasmus Smith of Nantucket. I was born here, went to school here. I own half an acre next to my own house lot, that’s all. But I was planning to send my kid to college on it someday.”

“Donald Hemenway, Shimmo. Likewise. I’ve scrimped and saved to buy that piece of land I own on the south shore. Used to go there as a boy and watch the waves roll in. Always dreamed of living there, building a house there. Had two jobs the last couple of years, trying to pay for it. My wife worked too, babysitting. So we could have a place of our own, not live with my folks anymore. Jesus, what was that?”

They were all turning around, craning their necks over their shoulders looking at Homer, who was sprawled on the remains of his four-legged stool. His cloak of invisibility had evaporated like the emperor’s new clothes.