![]()

stress and the american kid

Life moves pretty fast. If you don’t stop and look around once in a while, you could miss it.

FERRIS BUELLER, in Ferris Bueller’s Day Off

![]()

In 2014, the American Psychological Association did a study of stress in American life. They found that the most stressed group in America are teenagers. If you’ve spent time with a teenager lately, they could have told you that—or maybe they already did.

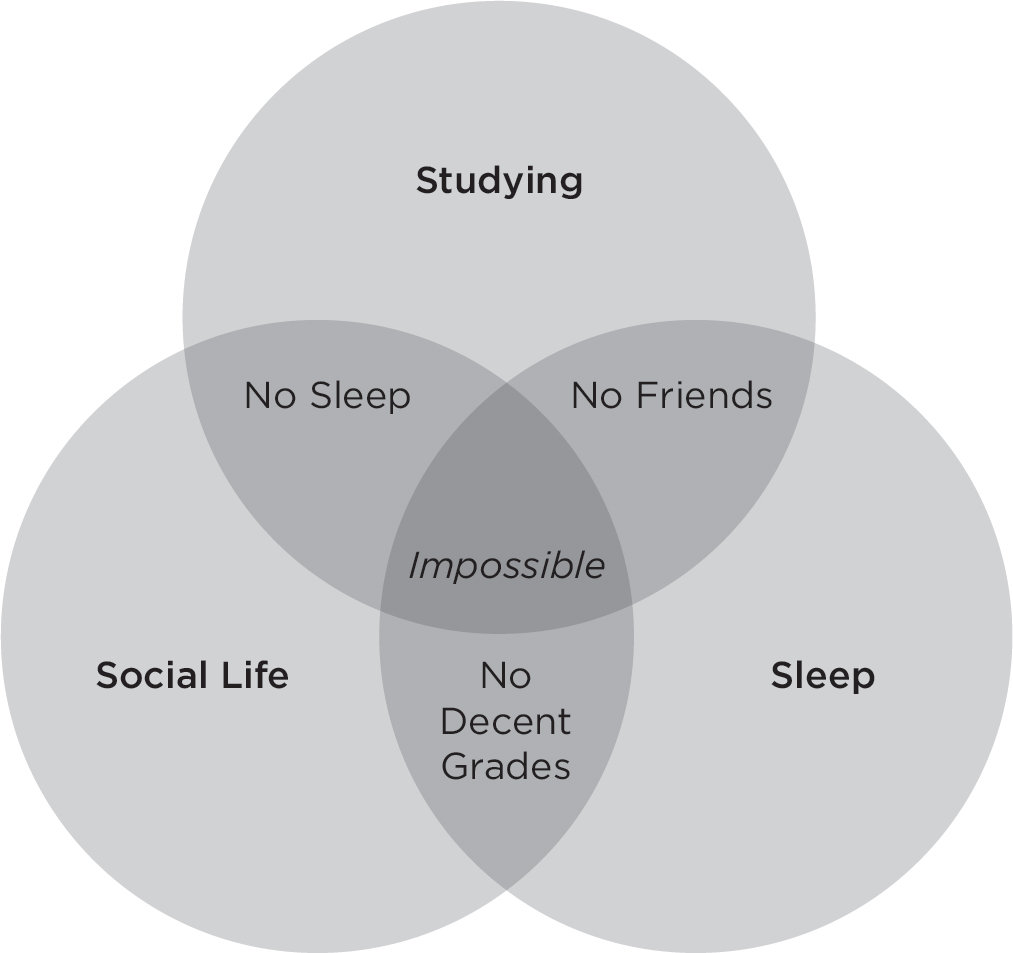

Figure 1 shows a Venn diagram making the rounds online. “The Student Paradox” is funny, to be sure, but it’s all too relatable for most teens. And this diagram doesn’t include other issues, such as caring for a sick parent, dealing with a brother in prison, working an extra job to help keep your parents’ house out of foreclosure, and other stresses that many teens are under.

It’s not just teens who are under stress. Whether I am speaking to kids in the inner city or students on manicured university campuses, the concerns I hear are the same. Kids of all ages worry about whether they will have a future, given the wars and environmental devastation affecting the planet. They worry about the economy, violence, poverty, and prejudice. It’s heartbreaking to hear a slender seven-year-old girl in the suburbs tell me she is too fat to have friends, or an eleven-year-old boy in the city tell me the only way he will live past twenty is if he’s in jail. No matter what background a kid is from, suffering and fear are universal.

Not only are kids under more stress, but they also have fewer skills for coping with it. Overburdened parents and teachers don’t know how to help; schools are cutting life skills programs to make room for high-stakes testing. Yet if young people don’t learn to manage stress by the time they hit their teenage years, they are hardly likely to learn later. Automatic responses to stress are learned at an early age and reinforced by life experiences. Stress, and kids’ responses to it, are contagious, spreading from kid to kid and through schools and families like this year’s flu, leading to long- and short-term negative effects on physical health, mental health, and learning. The good news is that mindfulness and compassion are contagious as well.

FIGURE 1 The Student Paradox: pick two

How We Usually Respond to Stress

Fundamentally, stress is a response to fear, real or perceived. Humans are hardwired to respond to fear in just a few ways. Our children facing SATs today react in much the same way that our ancestors did when facing a saber-toothed cat. Unfortunately, we haven’t evolved that much.

The following exercise, adapted from one taught by Mindful Self-Compassion teachers Christopher Germer and Kristin Neff, demonstrates two of the body’s built-in responses to stress.

![]()

Close your eyes and hold your hands in front of you, making tight fists. As you do, ask yourself these questions:

![]() What do you notice in your body? In your mind?

What do you notice in your body? In your mind?

![]() What kinds of emotions are you feeling?

What kinds of emotions are you feeling?

![]() What kinds of thoughts are you having?

What kinds of thoughts are you having?

![]() When during the day or during the week do you tend to feel this way?

When during the day or during the week do you tend to feel this way?

![]() How does your breath feel right now?

How does your breath feel right now?

![]() How open or closed do you feel?

How open or closed do you feel?

![]() How energetic do you feel?

How energetic do you feel?

![]() How would it be to feel like this all of the time?

How would it be to feel like this all of the time?

Now release your fists and drop your hands. Slump over and slouch, your head falling toward your chest.

![]() What do you notice in your body? In your mind?

What do you notice in your body? In your mind?

![]() What kinds of emotions are you feeling?

What kinds of emotions are you feeling?

![]() What kinds of thoughts are you having?

What kinds of thoughts are you having?

![]() When during the day or during the week do you tend to feel this way?

When during the day or during the week do you tend to feel this way?

![]() How does your breath feel right now?

How does your breath feel right now?

![]() How open or closed do you feel?

How open or closed do you feel?

![]() How energetic do you feel?

How energetic do you feel?

![]() How would it be to feel like this all of the time?

How would it be to feel like this all of the time?

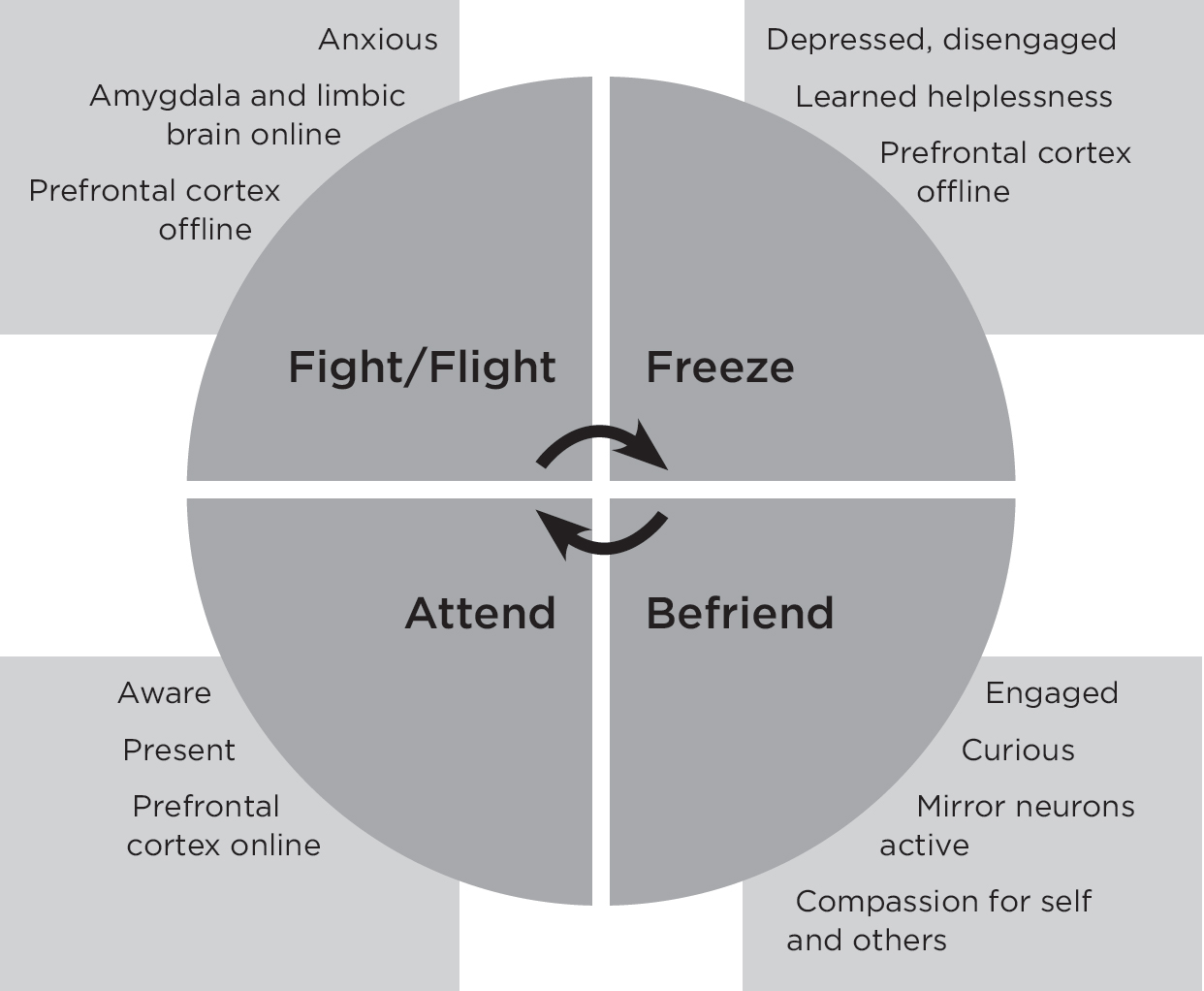

The first position, making fists, turns on the fight-or-flight response to stress, which helps us either fight off what’s stressing us out or run away from it. We tend to feel this way in traffic, on that busy day when we open our email to twenty new urgent messages, when our phone starts ringing, and when our child just vomited on the floor as the dog starts barking.

When we’re in fight-or-flight mode, our breath is constricted. In fact, our whole body is constricted, along with our mind and heart. It might feel that the slightest thing will set us off—probably because it will. We are on guard, closed off to everything except signals of danger. In our brain, the part called the amygdala (sometimes described as the “reptilian brain,” “caveman brain,” or “Incredible Hulk brain”) is flaring up, while the prefrontal cortex, where we do our best thinking, is shut down. We are thinking only about ourselves and the next few seconds; we are not thinking about the big picture, let alone experiencing compassion or the perspective of others. When we are in this mode, our filters only let in signs of danger, and they interpret even neutral or safe stimuli, such as a helpful parent or teacher, as threats or dangers. Cortisol, the stress hormone, is coursing through us, blocking the brain receptors for oxytocin, the hormone that allows us to feel love, compassion, and other cuddly emotions. The fact that fight-or-flight blocks our compassion explains why we’re not willing to lose three seconds by letting someone merge when we’re in terrible traffic, or why we snap at our partner or kids after a tough day at work. It perhaps also explains something about bullying and violence in high-stress schools. The body and brain are sending the message that everything is a threat, and there is no room in our response for compassion or understanding.

Many kids spend much of their waking life in fight-or-flight mode, their bodies reacting to danger even when there isn’t any. Many describe the fight-or-flight posture as powerful, but its power isn’t sustainable. The fight, or attack, response appears as aggression. The flight, or avoid, response manifests as anxiety. The long-term effects of a sustained flight-or-flight stress response are devastating to both mental and physical health, affecting everything from mood and the ability to think clearly, to cardiovascular health, immune functioning (after all, who needs long-term immunity for short-term survival?), and metabolism (yes, all this stress is partly to blame for the obesity crisis), to our relationships.

Too much time in fight-or-flight can cause kids’ brains to become rewired for reactivity, making it hard for them to access their own wisdom or think clearly. Parents and teachers may see kids spend hours studying and filling their brains with information, or therapists may help them build a strong set of coping skills, but the kids can still bomb a test or lose their cool in the important moment because they don’t have the bandwidth to access their prefrontal cortex or their best self in the moment that counts.

Let’s consider the second position, which demonstrates another built-in stress response. The slumped-over position represents the freeze/submit response to stress or danger, which gets less press than fight-or-flight. In the modern adult world, we might call this response the four-o’clock-on-a-Friday feeling. Animals in the wild sometimes respond this way to threats; they freeze, hoping to blend in with their surroundings so predators won’t see them, or they play dead, hoping to fool predators into leaving them alone. When this response is pervasive, behavioral scientists call it learned helplessness or even depression, which is another reaction to chronic stress or chronic trauma. Behaviorally, it manifests as giving up, turning inward, and shutting out the world. We might all call it the “f– it” response, and see it in ourselves, or in those kids who slump in the back row, appearing to have given up. In the freeze/submit state, too, signals of safety are filtered out, and reasons to give up are filtered in, reinforcing the depressive cycle.

While the freeze/submit response has its advantages and can even feel good, like fight-or-flight it is unsustainable. Giving up is no way to approach an athletic competition or a college interview, and repeated over time it leads further into depression and avoidance.

Both the fight-or-flight and freeze/submit responses have evolved to work well for the physical dangers that our hunter-gatherer ancestors faced, but are ineffective in the face of the emotional dangers and emotional stresses that the modern world presents, where the threats are less to ourselves than to our self-concepts. We don’t entirely understand why some people react with aggression, some with anxiety, and some with depression. It may be due to our brain’s neural wiring. It may also be due to a combination of genetics, cultural conditioning, and early attachment (or lack of) to caregivers.

The previous exercise with your hands allows you to experience the way a child, or an adult, responding to stress perceives and interacts with the world. The fight response probably looks familiar to anyone who has spent time with an angry child. The flight response belongs to what we might call an anxious child, and the freeze response to a depressed or traumatized child.

Cultivating Skillful Responses to Stress

The good news is that fight, flight, and freeze/submit are not our only options when responding to fear and stress. Today, biologists are studying two other responses to stress built into our bodies and mind. Because we tend not to cultivate these responses in ourselves, many of us rarely experience them.

To show you what I mean, let’s return to our demonstration exercise.

![]()

Sit or stand up, holding your body not too tightly, not too loosely. Extend your hands out in front of you, palms up and open.

![]() What do you notice in your body? In your mind?

What do you notice in your body? In your mind?

![]() What kinds of emotions are you feeling?

What kinds of emotions are you feeling?

![]() What kinds of thoughts are you having?

What kinds of thoughts are you having?

![]() When during the day or during the week do you tend to feel this way?

When during the day or during the week do you tend to feel this way?

![]() How does your breath feel right now?

How does your breath feel right now?

![]() How open or closed do you feel?

How open or closed do you feel?

![]() How energetic do you feel?

How energetic do you feel?

![]() How would it be to feel like this more of the time?

How would it be to feel like this more of the time?

While still upright, place one or both hands over your heart. Feel the warmth of your hand(s).

![]() What do you notice in your body? In your mind?

What do you notice in your body? In your mind?

![]() What kinds of emotions are you feeling?

What kinds of emotions are you feeling?

![]() What kinds of thoughts are you having?

What kinds of thoughts are you having?

![]() When during the day or during the week do you tend to feel this way?

When during the day or during the week do you tend to feel this way?

![]() How does your breath feel right now?

How does your breath feel right now?

![]() How open or closed do you feel?

How open or closed do you feel?

![]() How energetic do you feel?

How energetic do you feel?

![]() How would it be to feel like this more of the time?

How would it be to feel like this more of the time?

The position with hands up and out represents a stress response called attending. This is a qualitatively different stance than fighting, fleeing, or freezing. It is attending to what is actually here. In this stance, we are likely to feel open, awake, and alert, yet calm. We are settled without being sluggish. Rather than avoiding, we face directly whatever is in front of us, whether we like it or not, and we maintain a clear and receptive mind. We might think of this attentive state of body and brain as mindfulness.

When in this mindful, attending response, we can think fully and creatively, using all of our brain. We can focus on both the big picture and what’s right in front of us. We can breathe easily and deeply, and as we do, we take in accurate information about the world around us and inside of us. In the brain, the prefrontal lobes are back online, and the amygdala, the internal alarm system, is calm, without stress hormones jamming up the system. In the attend response, we are not passive, but alert and awake.

The last position, with one or both hands over the heart, recreates the befriend response. We can think of it as compassion and self-compassion. Not only are we staying present for the stress, for what is difficult for us in the moment, but we are also actively caring for ourselves in that moment and, in the process, learning to befriend the difficult emotions we are having. We can all begin to learn from our emotions, our inner voices, and care for them properly. In the process, we begin caring for ourselves and, in turn, caring for those around us.

You might take a moment to reflect: which of these responses are the best mental state for your kids (or yourself) to be in as they negotiate a new curfew, head into an exam, or approach another potentially stressful situation? The attend and befriend responses are healthier and more sustainable than fight, flight, or freeze/submit, and these too are hardwired into our neural systems. For example, in 2013, I was teaching in Europe when I got news of bombs exploding near the finish line of the Boston Marathon, in my hometown. My first instinctive reaction was to grab my heart, an unconscious, automatic gesture of self-compassion. So it’s not that one is better, it’s that some are better for certain contexts. So why do we usually default to fight, flight, or freeze/submit responses? Because we haven’t cultivated our natural attend and befriend responses or reinforced them when they occur.

That is where mindfulness practice comes in. Using practices that open us up, as in the second part of this exercise, we cultivate new types of awareness and, in doing so, retrain our brains to give us the option of responding to stress with attending and befriending, instead of automatically defaulting to the limiting and draining responses of fight, flight, and freeze/submit. We can also use these practices to help our kids cultivate their attend and befriend responses, so they can find the feelings of open, calm alertness and compassion for themselves when they need it most. Running through this four-position exercise is a good introduction to mindfulness; giving kids or adults the experience of mindfulness through position three will always be more powerful than defining it for them.

When I use this exercise with younger kids, I joke that in the first two positions we are acting and moving like a robot or a rag doll, and in the second two positions we are acting like human beings. Another friend describes these as tiger energy, sloth energy, and swan energy. You or your kids can also playfully say to yourself in fight-or-flight, “I’m calm,” or when slumped over, “I can do it!”, or in the attend position, “I’m so stressed out,” or in the befriend position, “I’m a complete failure.” It’s almost comical how wrong the words feel.

It’s not that stress is bad. We just need to better match our responses to the situations we find ourselves in. Attending and befriending are not the best responses all the time; sometimes we and our kids deal with real danger, and to survive we need to respond by fighting, fleeing (as when a car darts out in front of us), or “freezing” and just vegging out. At first, the attend and befriend responses may make us feel vulnerable, and some kids may not be physically or emotionally safe if they respond in these ways in their neighborhoods or homes. Had I been at the finish line of the Boston marathon when the bomb went off, I would have wanted to be in fight/flight until I reached safety, where I could shift into attend/befriend for myself and others. As adults, we can help kids find spaces where it is safe to practice the attend and befriend responses, so they can kick in when appropriate.

FIGURE 2 Ways we can respond to stress

We used to think that the brain we were born with was the one we were stuck with, once it finished growing in our late teen years. But in the last decade, research on neuroplasticity—the ability of our brain to change and grow, like a muscle, as a result of our actions and thoughts—tells a different story.

The brain is a lot like the body. We are born with a set of physical parameters, but if we eat right, take care of ourselves, and work out, we can build muscle, flexibility, and endurance. We can also change the shape and size of our brain, boosting concentration, flexibility, and intelligence and building new neural pathways and networks, by working out our brain, particularly with mindfulness and related practices.

My friend and colleague Sara Lazar, a neuroscientist at Harvard Medical School, has received a lot of attention for scanning the brains of mindfulness meditators with fMRI machines. Her research found exactly that—just as with physical exercise, areas of the brain that are active during mindfulness meditation actually grow with practice.1

The main area where growth occurs is in the prefrontal cortex, the area located right behind the forehead. This region is home to our executive functioning; it is the command and control center, where analytical thinking takes place. Here we see the future, understand consequences, see possibilities, and construct plans and strategies to achieve our goals.

This part of the brain also allows us to suppress impulses and not act on every emotion. Attention regulation and what psychologists call working memory live here, keeping us focused and on task, holding information on our cognitive desktop. Many interactions between emotion and thought occur here, as we make sense of emotional signals, then form moral and rational decisions.

Low activity and smaller size of the prefrontal cortex is correlated with psychological conditions such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), substance abuse and other problematic behaviors, impulse control problems, schizophrenia, distraction, depression, and mood disorders.

Interestingly, this was the last area of the human brain to evolve. You could say that the prefrontal cortex is what makes us human. It is also the last area to develop over our lifespan, reaching full development only in our mid-twenties. Research now suggests that, in males, it isn’t fully developed until the late twenties. (Insurance and car rental companies, not to mention parents and teachers and anyone who tried to date in their twenties, figured this out long before scientists.) Research on mindfulness has found improvements in sustained attention (listening to the teacher for the entire class) and selective attention (ignore the spitball flying past), both of which take place in the prefrontal cortex.

The insular cortex, located deeper in the brain, is also active during meditation and grows through regular practice. This region controls visceral processes, including regulating our heart rate, breathing, and hunger. The insular cortex also assists with emotional regulation, the integration of thoughts and emotions, and awareness and self-awareness. Mirror neurons, which give us the ability to put ourselves in another person’s shoes and have compassion for them, are located here. This area is often smaller in people with severe mental illness, including bipolar disorder and schizophrenia, yet it appears to get larger with even short-term meditation. Just as our muscles are active during physical workouts, these areas are active during mental workouts and get bigger with repeated use.

A few other brain regions also show positive changes with mindfulness meditation. Researchers believe the temporoparietal junction houses many aspects of emotional intelligence, including the abilities to see situations in a larger perspective, to see the perspective of others, and to consider the larger consequences of actions and behaviors. The hippocampus is important in memory and learning, both learning in the classroom and learning from past behavior. This part of the brain is smaller in patients with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and in people who struggle socially. The hippocampus helps us respond appropriately to a situation by getting information from the prefrontal cortex, which will help us to choose the wisest action. The posterior cingulate region, which allows us to shift from a self-centered perspective to the big picture, is also changed through mindfulness meditation practice. Other research has found that mindfulness meditation alters our brain-wave patterns in the short and long term to patterns associated with greater happiness.

FIGURE 3 Research on mindfulness shows that it has a variety of positive effects.2

While some parts of the brain become bigger, stronger, and more active with meditation, other parts of the brain get quieter. One significant change happens in the amygdala, the region most commonly associated with the fight-or-flight and freeze/submit responses to stress, as well as with depression. When the amygdala (caveman brain) is active, the prefrontal cortex (the civilized brain) shuts down, and vice versa. As described earlier, when the amygdala is active, we see threats everywhere and can’t think clearly. As it calms down or shrinks, our perspective of danger becomes more realistic, our levels of stress decline, and we can respond rationally rather than react irrationally to stressful events.

The research on mindfulness is well established and growing all the time, from a few dozen studies a year just a decade ago to a few thousand studies in recent years. Figure 3 summarizes what some of the recent research on mindfulness tells about the effects mindfulness can have.

Kids’ Brains and Mindfulness Practice

While the brain is always “plastic,” or changeable, it is most plastic during childhood. Because children’s brains are still developing, they can learn, adapt, and change faster than the brains of adults. (Don’t worry, the research shows that it’s possible to change your brain and make it calmer, more focused, and less reactive at any age—so you can teach an old dog new tricks!) We can set kids on a course of healthy brain development across their lives through early mindfulness practice.

Consider the less happy times in your own home, the children in your classroom that have a tendency to get under your skin, the types of referral questions that you get in your therapy office. When I ask this question at workshops, I hear the same responses over and over again: Moodiness. Impulsivity. Unhappiness. Aggression. Self-centeredness. Lack of perspective. Failure to see consequences. Questionable judgment. Mood swings. Emotional thinking. Short attention span. Poor planning. Reactivity. Executive functioning deficits. Hypersensitivity. These are typical of a brain in development. But there is great evidence that mindfulness and related practices have positive effects on the brain regions that are most important to emotional balance, calm, and resilience, and all kinds of research showing the ways in which mindfulness helps kids with these issues.

You may be thinking to yourself, “That’s all well and good, but how is my moody adolescent who can see only five seconds ahead going to sit down on a cushion and meditate?” The answer is, they don’t have to. The next chapters will give you dozens of practices that are just as helpful as formal meditation and don’t involve sitting still or take much time.

It’s important to know that whether or not our kids practice, if we adults do everyone benefits from the infectious calm, clarity, and compassion fostered by mindfulness. When we can stay balanced with our own practice as our kids enter challenging years—whether it’s the terrible twos or the terrifying teens—those phases go more smoothly for everyone.

BRAIN SCIENCE—IT’S NOT JUST FOR ADULTS

Understanding their own brains is empowering and motivating for kids. A study at Stanford examined how students’ understanding of intelligence changed their work habits.3 Two separate groups of middle schoolers were given a brief workshop in study skills, with a single difference: one group was taught about neuroplasticity and told that they could change their brains and become smarter by working hard. The kids from that group were easy to spot months later: they had better study habits and grades.

Kevin, a young man I work with, was skeptical about why he needed to address his stress. He had aced all of his science Advanced Placement tests and wasn’t about to do anything in therapy without grilling me on the scientific evidence. I explained the mindfulness research and sent him some articles. Now he actually likes to visualize his prefrontal lobes growing ever so slightly during his mindfulness practices.

I’ve explained to many kids who see themselves as impulsive or just “bad” that they simply need to give their brain some exercise. When they take that perspective, they are able to let go of some of their shame and self-blame and begin to feel better about themselves.

Slowing Down Our Minds

Stress, like death and taxes, is a certainty in life. But too often, our reactions to stress make everything—physical health, mental health, and thinking—worse. Besides reshaping our brains and helping us cultivate better responses to stress, mindfulness practices provide counterbalances to our busy world, because they encourage us to slow down, stop the rush, be instead of do, and experience instead of think. These slow moments are often the moments when we feel and are at our best. Slowing down and being a little vulnerable is not easy, and for many kids, it may not feel safe. The world can be a scary place, but we can help them find those moments when they can be more mindful.

Consider where you do your best thinking or come up with your best ideas. Many people say, “In the shower.” Why? Because we are relaxed, warm, comfortable, and often not in a rush. There are strong sensory stimuli—sounds, smells, sensations—that ground us in the present. Or perhaps you, like other great thinkers throughout history, receive insights as you daydream or drift off to sleep. Psychologists call this cognitive process incubation, and have discovered that flash insights are most likely to burst from the unconscious into the conscious mind at these relaxed moments, not when we are actively trying to make them happen.

Research shows that when the brain is relaxed, it takes in the big picture and opens to new ideas, making important new connections. The bumper sticker saying “Minds are like parachutes, they function best when open” does not just apply to politics; it holds true in learning, relationships, and creative approaches to life challenges. Mindfulness practices open the mind in just this way. Think back to the exercise of making a fist: how clear were your thoughts compared to when you held your hands open in front of you?

For kids, the brain relaxes not only during mindfulness practices but also in free play, recess, vacations, nap time, daydreaming, doodling, and other nonacademic activities, all of which are falling by the wayside in our test-driven schools and achievement-driven culture. Young people from all walks of life are falling into the busyness trap. They are frequently overbooked and distracted, unfamiliar and uncomfortable with slowing down. We are speeding up our kids all the time, neglecting downtime or playtime in favor of more doing. The romantic notion of childhood as a time of wonder and freedom is slipping away.

While “doing” is important, it also exacerbates stress. The habit of staying busy gets hardwired into our brains at a young age, making it even more vital that kids learn how to slow down, as well as manage their responses to stress, before they become adults. There are many theories about why there has been such an explosion of mental illness in young people. I don’t know the answer, or if there is even one—but this culture of doing and distraction certainly makes it worse.

The culture of “doing” has become ubiquitous. We can see it in all corners of our society, from the inner city, where kids are raised by video games inside or gangs in the streets outside, to the suburbs, where the culture of helicopter parenting emphasizes the college rat race, and kids are shuttled from soccer to SAT prep to saxophone lessons, all before homework. Everywhere, play, authentic connection, and curiosity are passively, if not actively, discouraged. I’ve encountered parents who have their sixteen-year-olds’ “free time” scheduled into fifteen-minute increments and ask me when to fit in mindfulness practice. (I tell them, don’t.) I’ve met college students whose parents track their phones by GPS to check on where they are at 3 a.m. A teacher at a workshop recently told me his school was cutting its lunch period from twenty to eighteen minutes. These are the extremes, to be sure, and yes, they may come from a place of concern, but they prevent children from learning from their own experiences. Kids are up to midnight or well past midnight online or studying, with no time to become curious about what matters to them.

Today’s young people have less experience with slowing down and exploring the world around them, let alone exploring the beautiful worlds inside themselves. Many young adults with anxiety and depression say that the hardest times of day are when they have time to themselves. Yet getting curious about what’s inside us is how our natural values arise, how true learning and growth takes place. When the cultural messages tell kids to ignore their experience, or that how they feel or look or what they do is wrong, they are left lacking in emotional intelligence and unprepared for adulthood. MIT sociologist Sherry Turkle reminded us in a 2012 TED talk, “If we don’t teach our children to be alone, they’re only going to know how to be lonely.”4

I titled my first book Child’s Mind to play on the Zen notion of beginner’s mind. Zen master Shunryu Suzuki describes it this way: “In the beginner’s mind there are many possibilities, but in the expert’s mind, there are few.”5 The title Child’s Mind was a call for adults and young people to return to the naturally contemplative state of childhood existence, that moment-to-moment open awareness with nonjudgment and acceptance and reflection. Contemplation, curiosity, wonder—these are the values of the beginner’s mind. As we’ll explore in chapter 2, experiencing things in their essence, for the first time, without judgment, is what mindfulness is about.