1

“Of Course I’m Proud of My Country!”

Michelle Obama’s Postracial Wink

In the months leading up to the selection of the 2008 Democratic nominee, Michelle Obama was widely considered to be a liability to her husband’s campaign. In both anonymous online spaces and mainstream media outlets, journalists and lay-commentators alike attacked Ms. Obama with astoundingly racist, sexist vitriol. Black feminist theorist Brittney Cooper summed up these comments as focusing on Obama as “unpatriotic, unfeminine, emasculating, and untrustworthy,”1 while sociologist Natasha Gordon described how Obama “has been charged with epithets ranging from being ‘ape-like’ to a ‘terrorist’ to a ‘bitter, angry Black woman’ to President Obama’s ‘baby mama.’”2 If online comments were crude and explicit, mainstream press sentiments circulated barely sublimated racialized codes that amounted to one underlying assumption: Michelle Obama simply wasn’t the image of a First Lady.

Then, within a matter of months, the First-Lady-to-be’s popularity surged. While she would continue to dodge barbs from the extreme racist fringes of the country, her quickly climbing ratings demonstrated that the country was falling in love with Michelle Obama, mom-in-chief, down-to-earth fashionista. She was still an Ivy League-educated attorney, like her husband, but she didn’t make a big deal about it. Alongside Laura Bush, Michelle Obama enjoyed higher favorability ratings than any First Lady since Pat Nixon.3 What happened to precipitate such a flip? Did the country somehow magically become less racist and sexist, or did Michelle Obama do something to win the hearts and minds of America? This chapter explores one specific media event that helped create this shift, in which Michelle Obama played the ultimate magic trick: postracial resistance through strategic ambiguity.

* * *

Imagine that it is November 5, 2008, and you are Michelle Obama, on the cusp of potentially becoming the first Black First Lady of the United States.4 Along with the virtues of femininity, strength, maternity, humility, and grace, you must perform constant restraint. You must be cognizant that each and every one of your words is being scrutinized, taken out of context, and magnified for the world to dissect. You are in the midst of a constant media circus of neither your own creation nor desire. You must not only grin and bear the media’s obsession with you, but present yourself as happy to be in the midst of such a spectacle. How do you face open, unbridled hostility? And not just any type of hostility, but a particularly virulent, racist, misogynistic, anti-Black woman brand. What do you do?

This conundrum—how, as a minoritized subject, to negotiate a metaphoric straitjacketing in response to racist, misogynistic verbal attacks—is, of course, not just an issue for a potential First Lady. Ironically, because of her success, those “of difference,” whether race, gender, sexuality, class, or ability, received arguably fewer options to respond to the vitriol targeting our bodies in the Michelle Obama, first Black First Lady era. “We” were ostensibly past discrimination and even past identity.5 The mainstream media presented the ubiquitous cultural assumption that all Americans reached a moment “after” or “post” oppression that defaulted to “after” or “post” race.6 Scholarship exposing the danger of these posts has exploded in the past decade, illuminating, as communication scholar Catherine Squires, puts it, “the material stakes of so-called identity politics and how the rhetorical shenanigans of the post create another layer of difficulty in decoding and detecting regressive, oppressive tactics.”7

Postrace has been interdisciplinarily deconstructed by sociologists, critical race scholars, critical theorists, and communication scholars.8 Under the rubric of postrace scholarship, some authors such as geographer Anoop Nayak, building on the work of Paul Gilroy, celebrate how “post-race ideas offer an opportunity to experiment, to re-imagine and to think outside the category of race”;9 but others such as sociologist Brett St. Louis warn against “putative post-racial attempts to dismantle the meaningful symbolism and materiality of race.”10 Crucially, race/gender media studies scholars, from Mary Beltran, to Julietta Hua, to Kimberly Springer, have centered representations of women of color in their conjoined critique of race and gender and postrace and postfeminism, connecting illuminating yet largely single axis debates—race or gender—in postrace and postfeminism.11

To read Michelle Obama’s strategic ambiguity, and how effectively she resisted the ideology of postrace by using the tropes of postrace against themselves, I investigate two of her speaking events that were heavily hyped by the media: a before and after picture, if you will. In the first, Michelle Obama was verbally attacked for her line at a February 2008 campaign rally: “for the first time in my adult lifetime, I’m really proud of my country.” In the second event, four months later on the daytime talk show The View, Obama used strategic ambiguity to address criticism of these comments.

To make sense of the landscape of talk about and talk by Michelle Obama, I did an initial Lexis-Nexis search of the major U.S. newspapers using the terms “Michelle Obama” and “race,” from January 1, 2008, when Michelle Obama began to occupy the national consciousness after Barack Obama became a viable candidate following his January 2008 win at the Iowa caucus, to September 24, 2009, the date of my first search. This search produced a total of 959 articles, of which I found 84 to be particularly relevant because they showed sustained engagement with issues of Obama and racialization. From these eighty-four articles, I found that the “pride” event (in February 2008) and its reframing (in June 2008) was the most comprehensive “media spectacle,” to borrow media studies scholar Douglas Kellner’s phrase, because it encapsulated a number of the newspaper articles’ themes.12 These included Michelle Obama’s providing “Black authenticity” to Barack (negatively spun in this event, equating Blackness with bitterness); the obsession with her body (through the constant refrain of her height, described as “5’11” or “just shy of 6 feet,” and descriptions of her “fit” and “athletic” body); and, most importantly for my purposes, her Americanness, patriotism, and the American Dream. (Choosing an event with clear beginning and ending dates also helped me avoid, in the words of Gilbert Rodman, “one of the occupational hazards of studying contemporary culture … It’s a constantly moving target.”13) Michelle Obama affords minoritized subjects a model of how to resist the assumption that we are in a postracial culture, or how, to flip Audre Lorde’s famous phrase, to dismantle the master’s house with his tools in our new era of sanctioned racialized misogyny.

If, as sociologist Patricia Hill Collins writes, “in the post-civil rights era, the power relations that administer the theater of race in America are now far more hidden,”14 minoritized postcivil rights subjects need new ways to become powerful actors. Michelle Obama’s postracial resistance through strategic ambiguity provided us with this new model. Although the intentions behind her scripting are impossible to determine, I do believe that, as communication scholar Mary Kahl argues, Michelle Obama’s public statements exhibited an “awareness of the persona she is fashioning for herself.”15 Through her reframings, redefinitions, and coded language, Obama demonstrated her refusal to accept when anti-Black, anti-woman controlling images were superimposed by hateful conservative and fetishizing liberal media culture onto her body.

Situating Postrace

To make sense of Michelle Obama’s strategic refutation of postrace, and build on the previous chapter’s discussion of the theory and its uses, I briefly historicize some of the metatheoretical moves that have enabled twenty-first century post ideologies. The idea of being past identity is not new, although in this historical moment the popular media often presents it as such. Postracial ideology, reflecting both neoconservative and neoliberal leanings, can be traced not only to reactionary political thought but also to what were largely understood to be liberatory political and academic movements, at least in their time. I read central tenets of postrace against three landmark movements of thought and activism: postmodernism, civil rights and feminism, and women of color theory’s interrogations of identity. To answer how Michelle Obama resists postrace, I investigate how we have arrived at a moment in which postrace conscribed the landscape of talk by and around Obama.

In the Obama era, the media presented postrace, intended to mean post-bias, somewhere along the spectrum from fact to aspiration. In reality, the discourse and concomitant ideology of postrace dictated a contemporary, media-fueled moment in which “different” racialized and gendered identities (those of color and those female) were somehow magically granted equal status and were therefore expected to agree that historic, structural, interpersonal, and institutional discrimination were exclusively in the past. Those who merely referenced race or gender, much less racialized or gendered discrimination or racialized or gendered “pride,” got dismissed or attacked by the popular media as outmoded, irrelevant, paranoid, or even themselves “racist” and “sexist.” Racialized and gendered disparities that abounded and dictated life chances were simply not allowed to enter into the ideological space of postrace. Scholarship that deploys the term postrace has a tendency to quickly breeze past both identity categories and structures of discrimination, to think through the “possibilities” inherent in leaving behind identity, as opposed to thinking through the possibilities inherent in leaving behind minoritized people or ignoring inequities. I argue here that postrace was a fabricated realm where race-blind fiction supplanted racialized fact. As differential outcomes and structural inequalities were silenced in postracial ideology, they were, in effect, allowed to continue, unfettered. Interestingly, the body did not disappear in the ideology of postrace. Instead, the body of color was symbolically important as its freedoms and successes, despite its markers of racialized difference, were used to measure progress from the civil rights era.

Postracial ideologies, while present for decades, emerged on a large-scale in the 2008 election campaign, when Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton became the top two Democratic Party contenders for U.S. president; they crescendoed after Obama’s election. These two firsts were offered up in the popular media as evidence of the United States emerging as a truly meritocratic state. This new millennium moment of postrace, in which the fiction of meritocracy became hegemonic, defined the incredibly restrictive landscape in which Michelle Obama, an African American female icon and then potential First Lady, was allowed to speak. When frank discussions of difference were verboten, hypervisible Obama had to couch her words as she carefully fought off her verbal attacks. With help from her media team, Michelle Obama skillfully used strategic ambiguity to create a counternarrative to controlling images of Black women. Ideologies, including what Stuart Hall called the formulation of identities, are never complete but always in flux; counterhegemonic narratives like Obama’s speak back.16

Michelle Obama deployed strategic ambiguity specifically in reframing and redefining ideologies such as “American” and “patriotism” and in speaking of race, class, and gender in code.17 In resisting, reframing, redefining, and coding, Obama used the tactics articulated in women of color theory, also known as the U.S. third-world feminism. Cultural studies scholar Michelle Habell-Pallán illustrates that, for more than 30 years, “women of color [have been] initiating and advancing a politics of difference … in response to liberal essentialist notions embedded in the women’s movement and scholarship as well as to ethnic nationalism.”18 Women of color theory does not refer to the scholarship produced by a demographic group but to a particular way of reading or of what literary theorist Valerie Smith calls a “strategy of reading simultaneity.”19 Smith builds on critical race theorist Crenshaw’s ideas of intersectionality, where “ideologies of race, gender … class, and sexuality … are reciprocally constitutive categories of experience and analysis.”20 These are the instruments with which Obama and, following her, we ourselves can cut through both her racist marking as a Black bestial body and her postrace framing as an exemplar of Black achievement and the sign of the end of racism.21

Postrace is the culmination of a narrative of progress from a past notion of identity categories as biased, discriminated against, and particular, to a current notion of identity categories as unbiased, discrimination-free, and universal. Postrace has clear resonance with postmodern scholarship, particularly that which is associated with fragmentation, pastiche, and a play of identity—with the denial of any fixed meaning. One node of postmodernism originated with Jean-Francois Lyotard, who expressed a certain “incredulity [toward] metanarratives,” whereby he questions the previously assumed-to-be-sacred teleologies of Enlightenment progress. In poststructuralism, too, an “identity” lost much of its integrity.22 For example, Jacques Derrida’s critique of the so-called scientific nature and objectivity of language in Writing and Difference assessed the “logocentrism” of structuralism and argued that language is ambiguous, unstable, full of “slippage,” constantly changing, and open in meanings, and that the self is not separate or singular but is rather a construct. Poststructuralist scholarship celebrated the fluidity of linguistic meanings. Similarly, today, postracial ideology champions the ostensible fluidity of racialized meanings;23 new millennium postrace culture claims that there is no singular essence to a racialized identity.

However, as the Michelle Obama case will demonstrate, in practice, post ideologies can lead to media and politics representing and sometimes even spotlighting different bodies, whether queer, disabled, of color, or working-class—but also rhetorically erasing them. In other words, when differences are visually present but disempowered and unremarked on they are devalued. Indeed, although bodies of color are often featured prominently in postracial culture, they can function as mere multicultural decoration or, in the words of media scholar Brenda Weber, operate as “a discourse of style as substance.”24

What does it mean for race and gender to have these same types of open meanings? Can changing our definition of race mean that we eliminate racialized and gendered stereotypes? Theorizing race and gender through a postmodern framework means that racialized and gendered identity remains unhistoricized and thus not recognized as the effect of historic processes of racialization or gendering? Postmodernism and twenty-first century postracial ideology—like neoliberalism—present identity as ambiguous, unstable, changing, open, fragmented, and, perhaps most importantly, the result of choice. Mainstream media representations play on many of these tropes in their coverage of Michelle Obama. Through postmodern notions of identity play, the dynamics of race—as well as gender—can become, in effect, elements of style. In her media representations, Michelle Obama’s gendered image signified elements of “girl power” culture: she was portrayed as a “strong woman” who could still be interested in ostensible frivolities (as a penchant for fashion is understood to be un-, anti-, or postfeminist) and yet not be dismissed as frivolous. At the same time, postmodernism could not only be spotted in talk about Michelle Obama: postmodernism guided talk and action by Obama and her media team. For example, during the election campaign, Obama often wore oversized pearls and her hair in a flip reminiscent of Jacqueline Kennedy, a lighthearted nod to what Vogue editor-at-large Andre Leon Talley called “a black Camelot moment.”25 Playing to a mediatized embrace of her fashion choices, Obama directed audiences away from her inside (as in second-wave feminism) and invited us to celebrate her outside (as in postfeminism).

Postmodern challenges to conventional iterations of identity must also be seen alongside 1960s and 1970s era civil rights and feminist activists’ articulation of identity. Both movements held explicit goals of exposing and challenging material, social inequality. Importantly, the media frequently represented Michelle Obama as the beneficiary of the civil rights and second-wave feminist movements: the press and Obama’s own media team focused on her “American Dream” story whereby, as the narrative goes, her working-class African American family produced two children who overcame the barriers of their neighborhood, their race, and their socioeconomic background to attend Princeton University and “make it.” This narrative was one of moving from lack of economic opportunity and racialized specificity to wealth and postracial universalism. This narrative wasn’t false; it was partial and it had an agenda. Obama’s story was contingent upon silences and exclusions as she omitted the realities of structural, institutional, and historical racism affecting the South Side of Chicago.

This example is of Michelle Obama controlling racialized narratives through postracial resistance and strategic ambiguity. In addition, scholars such as Crenshaw have illustrated how, in the service of political efficacy, civil rights and feminist movements scripted “authentic” Black and female subjects.26 The mainstream of both movements aligned themselves with the most empowered members of their respective communities: middle-class, straight White women in the feminist movement and middle-class, straight Black men in the civil rights movement. Thus, the leadership of the civil rights and the second-wave feminist movements was often reliant on singular, essential, bodily instantiations of identity. Forgotten were those with multiple marginalized or intersectional identities who crossed and fell out of categories, such as women of color. Identity was not at all “post” in such activist movements—unambiguous, stable, unchanging, authentic, bodily, status regulated inclusion.

Michelle Obama’s public statements and actions illustrated that she sought to challenge discrimination, even though she had to speak of materiality and inequities in code, particularly when discussing those dynamics as racialized or gendered. To be clear, however, post ideology relies on the narratives of the civil rights and second-wave feminist movements as the moments in which America already conquered inequality. Cementing discrimination firmly in the past helps prove that the twenty-first century is about the unequivocal success of the movements. We have now arrived at the “after” moment when inequality is over. Postrace as an ideology assumes that structural inequities, too, are relics of the past. In this vein, for example, a popular newspaper piece investigated Michelle Obama’s family tree all the way back to her last enslaved relative27—not to illustrate the legacy of enslavement’s effects on structural and institutional racism today but rather to note that we have so profoundly overcome a dehumanizing system that an individual with an enslaved relative ascended to the White House. For some who believed deeply in postracial ideologies, these pieces functioned as racism’s death knell.

But postrace is slippery. Although diametrically opposite in the realm of politics, women of color theory, along with scholarship by and about other minoritized and historically forgotten people, is yet another influence on postrace. Women of color theory was born out of a moment in which the identity fluidity and play inspired by postmodernism met the materialist, racialized, gendered, and most certainly identity-based concerns of liberation movements. Cultural studies scholar Michael Millner characterizes this scholarly moment as “a rich and sophisticated reconceptualization of identity—as performative, mobile, strategically essential, intersectional, incomplete, in-process, provisional, hybrid, partial, fragmentary, fluid, transitional, transnational, cosmopolitan, counterpublic, and, above all, cultural.”28 Millner describes authors such as Homi Bhabha, Judith Butler, Rey Chow, Paul Gilroy, Jose Esteban Munoz, and Eve Sedgwick as expressing “exhaustion around the whole project of identity.”

But the exhaustion, at least as it pertains to women of color theory, has been centered on the project of essentialism (a limiting litmus test of authenticity) and not the projects of identities (de-essentialized, open, multiple, and hybrid entities).29 Essentialism and identity are, of course, not one and the same. In many spheres of discussions of “difference” in arenas as varied as the popular press and communication scholarship, the slippage between identity and essentialism flourishes. Writings on identity, in and of themselves, are not necessarily stultifying. Although Millner describes certain critics as writing “past” identity in the 1990s, not all scholars are in agreement. For example, literary scholar Farah Jasmine Griffin, identifies that same decade as “one of the most intellectually exciting and fruitful developments” for Black feminist studies. Griffin points out that “it is quite likely that the latter critique of essentialism was made possible by the very terms and successes of Black feminist literary critics who were among the first to call attention to the constructed nature of racial and gender identity.”30 Grounded in the Combahee River Collective’s articulations of simultaneity, women of color theorists in the 1990s built on the work of sociologists Michael Omi and Howard Winant, specifically their classic formulation of race as materially, institutionally, and structurally constrained as well as fluid, performative, and mobile.31

Reformulating racial formation theory in light of women of color theorizing, we can see that acknowledging the constructed and the conscribed results in a denial of the either/or formulation and a celebration of the both/and, to borrow the language of Patricia Hill Collins.32 The body, although not the sole determinant of life chances or life choices, is essential and cannot be disregarded. Identity is, by these meanings, not essentially defined. The identity/essentialism slippage, as it flourished in popular discourse, helped produce the post era. Michelle Obama navigated this slippage by resisting racialized, gendered verbal attacks through redefining and reframing “traditional” ideologies. Her invocation of a highly feminized performance of postrace to fight against the racist/misogynistic effects of postrace is enabled by postmodernism, the civil rights and second-wave feminist movements, and women of color theory.

The reading tools of women of color theory help us see that Michelle Obama entered a public sphere in which, as Black feminist theorist Joy James writes, “commercial and stereotypical portrayals of Black females center on fetishized and animalized sexual imagery; consequently Blacks, females, and politics become effaced or distorted. Racial and sexual caricatures corseting the black female body have a strong historical legacy.”33 These caricatures are contradictory, ranging from diminished humanity, as James notes, and super-humanness, which is equally limiting in nature. bell hooks explains,

Racist stereotypes of the strong, superhuman black woman are operative myths in the minds of many White women, allowing them to ignore the extent to which Black women are likely to be victimized in this society and the role White women may play in the maintenance and perpetuation of that victimization.34

The “fragility of Whiteness,” to use education scholar Robin DiAngelo’s phrase, and White womanhood, in particular, silence discussions of Black stereotyping, and force figures like Michelle Obama to rely upon strategic ambiguity in order to make her interventions. Public refutations of postrace thrive in our media culture even as they must enter under the cover of postracial discourse, that is, by way of strategic ambiguity. Valerie Smith writes that “unacknowledged cultural narratives such as those which link racial and gender oppression structure our lives as social subjects; the ability of some to maintain dominance over others depends upon these narratives remaining pervasive but unarticulated.”35 To fight oppression, we need to articulate these cultural narratives. For women of color like Obama, explicit, uncoded speech on race and gender was simply not possible. But coded speech was still available. When she and others named minoritized and marginalized identities in code, code protected the message from outsiders’ scrutiny while making it available to insiders to decipher. Here is a material postmodernism: Texts are open enough to enable, in the words of rhetorician Leah Ceccarelli, a polysemy, “a bounded multiplicity, a circumscribed opening of the text in which we acknowledge diverse but finite meanings.”36 Thus, the performance of strategic ambiguity, twenty-first century postracial resistance by an iconic figure like Michelle Obama reinvigorates late twentieth century women of color theory.

The postracial resistance Michelle Obama performed, which the popular media at least did not read as resistance, is markedly different from opposition to “traditional” racism or sexism. The game has changed: There is no room for such conventional responses. When “old-school” civil rights and second-wave feminist responses explicitly naming racism and sexism erupt, critics dismissed them as irrelevant and even laughable, as in the public parodying of Al Sharpton and Hillary Clinton for being, respectively, too old-school civil rights or old-school feminist to speak to a twenty-first century Democratic party. Their insistence on seemingly conventional antiracist or feminist politics is portrayed as out of time and out of touch with twenty-first century America. Communication scholar Robin Means Coleman notes that Sharpton, for example, faced a “‘race card’ dismissal … in favor of the perceived ‘race in moderation’ political discourses of Barack Obama.”37 Michelle Obama should not be evaluated in the old binary framework of either “selling out” (in other words, not acting appropriately Black and female by failing to prove her race/gender credentials) or “being real” (in other words, acting authentically Black and female by proving her race/gender credibility). Instead, to resist postracial ideology, Michelle Obama deployed particularly feminized elements of postracial culture in her presentation of strategic ambiguity—she performed and subverted the hyper-feminized postrace that was available to her.

Pride Attacked

There were numerous events where the McCain campaign and the conservative media pilloried Michelle Obama in the 2007–2008 presidential election campaign season; she spoke back to each of them, deploying a sophisticated resistance to postrace. These included the ridicule directed at her because of a “fist bump” with Barack Obama at a campaign rally in St. Paul, Minnesota, in June 2008, and the parody of her as a Black Panther a month later on the July 21, 2008, issue of the The New Yorker. But perhaps the most attacked of all of Michelle Obama’s statements was her “pride” comment during a stump speech in early 2008. Carefully and critically examining Obama’s words helps to reclaim her humanity, which as legal scholar Adrienne Davis writes erupts through language, from the claws of the media.38

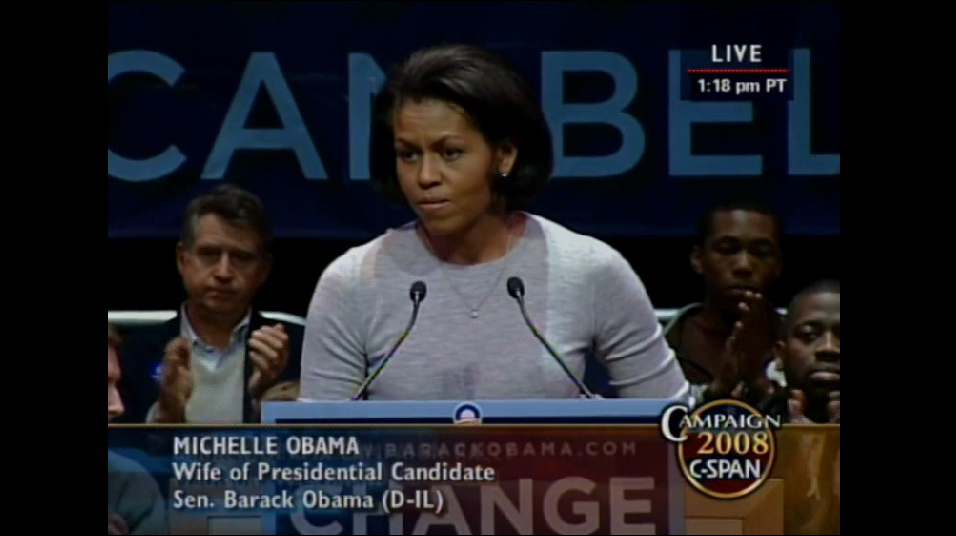

Figure 1.1. Michelle Obama’s “pride” comments. Screenshot from “Michelle Obama: First Time proud of USA,” C-SPAN, February 8, 2008. Viewed October 6, 2017. www

Michelle Obama made her “pride” comments during a campaign speech on February 19, 2008, first in Milwaukee and then in Madison, Wisconsin (Figure 1.1).39 In the television networks’ coverage of the speech, only Obama’s head and shoulders were visible in the frame; the rest of her body was concealed by a podium. She wore a crew-necked light gray sweater that accentuated her muscular lats, small pearl earrings, and a very thin gold necklace. Complementing this dressed-down look was her minimal makeup and no-nonsense bob. Obama spoke in a self-assured, even-toned voice. She was intent and focused and smiled infrequently during her remarks. In essence, her words, not her outfit, hairstyle, or personality, were the focus of this speech. She stated,

What we’ve learned over this year is that hope is making a comeback. It is making a comeback and let me tell you something, for the first time in my adult lifetime, I’m really proud of my country. And not just because Barack has done well, but because I think people are hungry for change.

Obama underscored her talk of “hope” by a vision of collective and not individual success: Her investment was not just in her personal family’s or her husband’s success, but in the usually overlooked folks, the “people hungry for change,” who were now being given hope that they were not going to be forgotten forever. She continued,

And I have been desperate to see our country moving in that direction and just not feeling so alone in my frustration and disappointment. I’ve seen people who are hungry to be unified around some basic common issues, and it’s made me proud. And I feel privileged to be a part of even witnessing this, traveling around states all over this country and being reminded that there is more that unites us than divides us.

In her insertion of “I” statements, Obama did not isolate herself from the people she rhetorically conjured but instead put herself in the category of the disregarded, those who have felt alone, frustrated, and disappointed. This functioned as code for minoritized people. But, also in code, Obama was clear to illustrate that the dispossessed were not simply racialized minorities; she inserted an intersectional critique, noting that class dispossesses people as well. In the final section of her remarks, Obama stated that the crowd must keep in mind,

That the struggles of a farmer in Iowa are no different than what’s happening on the South Side of Chicago. That people are feeling the same pain and wanting the same things for their families.40

Hence, working-class Whites, such as the “farmer in Iowa,” were cast out by the then-current Republican regime just as were working-class African Americans, such as those “on the South Side of Chicago.” What her message amounted to was that we, the cast out, needed to stand together in cross-racial unity to create change. The major news networks did not cover the last part of Obama’s remarks and, indeed, I only found Obama’s full speech on a C-SPAN feed.

Although Obama named race and class only in code, a clear element of postracial discourse, Obama’s call for collectivity spoke directly against the individualism inherent in postracial ideologies. She articulated a theory that Michelle Habell-Pallán credits women of color scholars with: “illuminat[ing] … the linkages … of economic exploitation and racialization.”41 Obama refused to be seen as a token or as an exceptional individual who has made it. Indeed, minoritized subjects who attain a degree of success are often portrayed as singularly exceptional and therefore apart from their communities. Black feminist scholar Carol Boyce Davies examines such a case in her analysis of former president George W. Bush’s Secretary of State, Condoleezza Rice. Davies describes the focus on individual success as “Con-di-fi-cation,” the political tactic of “exceptionalism as strategy.” The “media construction” of elite minoritized public figures such as Rice, Davies notes, involves “a typical singling out of one member of a subordinated group as many others with similar talents are erased.”42 Obama’s use of coded language allowed her to argue against such a singling out, an expression of anti-Con-di-fi-cation.

In this speech, Michelle Obama also reframed hegemonic conceptions of patriotism: It was not just the purview of those who were enfranchised but those who were disenfranchised, who were victims of racialized, economic abuse propagated by the very political structure of this country. For Obama, patriotism was, in the words of performance studies scholar D. Soyini Madison, “the ability to both love and critique, to both honor and re-imagine, to both recognize the noble possibilities of this country while interrogating its wrongs.”43 Obama provided us with an open enough text that insider readers accustomed to strategically ambiguous race/gender winks could indeed identify an intersectional, anti-racist message imbedded in it. There was inclusivity at the very core of this message, through Obama’s paralleling the similar plights of working-class Whites and Blacks.

But, despite what could have been acknowledged as a benignly multicultural moment to rhetorically unite the races, an amazingly ferocious media attack followed her remarks. I contend that her tone and appearance, which might be described by some viewers as more traditionally “feminist,” made some room for it. While the message Obama gave used major tropes of postrace—reframing, redefining, and coding—her more “feminist” look didn’t match, so postrace didn’t fly. As feminist, Obama is imaged as strong enough to take mediatized attacks, while as glam goddess, which she will soon after this event emerge as, she is framed as needing protection from such attacks. Michelle Obama only stopped being beaten up by the media later, when she created a hyper-feminized look and persona.

Conservative commentators (most prominently television news personalities Joe Scarborough and Sean Hannity) and the McCain campaign quickly picked up on a single portion of these comments, taken out of context: “for the first time in my adult lifetime, I’m really proud of my country.” Twenty-four hour cable news networks featured these comments around the clock as proof that Ms. Obama was bitter and un-American. They caricatured her, one cultural commentator said, as “emasculating, sarcastic, and bossy.”44 This is a type of “framing by foil,”45 to use rhetorician Dana Cloud’s phrase, whereby verbally denigrating one’s adversary produces the attacker’s image of him- or herself as all manner of positive attributes that are in direct opposition to the object of hate.

Cindy McCain, the very picture of a traditional (read: White) First Lady, picked up on Michelle Obama’s line that same day, saying at a campaign rally as she introduced her husband: “I’m proud of my country. I don’t know if you heard those words earlier. I’m very proud of my country.”46 Through attack, the Republicans portrayed Obama as unpatriotic. The very tone and tenor of this attack was intended to demonstrate their own so-called uber-patriotism. The Republicans’ slogan for the September 2008 Republican National Convention (RNC) was “country first”; they came out with “pride in country” merchandise immediately following Michelle Obama’s remark.

And, of course, the Republicans’ claim to the flag is legendary. Because of Republican policing of “authentic” patriotism, for example, Democratic candidates and their spouses, including Barack and Michelle Obama, were constantly scrutinized to see if they were performing patriotism appropriately. The signifiers of patriotism included the positioning of hands over hearts for the recitation of the “Pledge of Allegiance,” the prominent featuring of flag pins on jacket lapels, and the positioning of multiple flags in the background during public events and press conferences. Patriotism meant waving flags, not invoking images of the union of Blacks and Whites, as Michelle Obama conjured in her February 2008 speech. Strategic ambiguity also had a look in this particular case: it was not crewneck sweaters and minimal makeup.

The Glam Makeover: Success through Strategic Ambiguity

Obama’s positioning as disgruntled, upset, and unpatriotic throughout media coverage referenced the “Angry Black woman” stereotype, and one I will go into greater depth about in the next chapter on Oprah Winfrey. Media theorist Kimberly Springer points out that, in framing figures into this controlling image, the media fails to address one basic question: why she might be angry.47 Women of color theorizing, however, provides such an explanation. In the classic essay “The Uses of Anger: Women Responding to Racism,” Audre Lorde explains,

Women of Color in America have grown up with a symphony of anger at being silenced, at being unchosen, at knowing that when we survive, it is in spite of a world that takes for granted our lack of humanness, and which hates our very existence outside of its service … We have had to learn to move through [our anger] because we have had to learn to orchestrate those furies so that they do not tear us apart.48

Part of the way in which Obama “orchestrat[ed] those furies,” how she moved through what undoubtedly was anger at her attacks, was by deploying resistant postracial tactics through strategic ambiguity. In the aftermath of the media attack, Michelle Obama was forced to reframe, explain, and defend. She did so by choosing a certain type of media coverage—what media industries designate as women’s television programs and magazines—in which she used coded language to redefine and expand the limits of who is American. Women, and particularly White women, were a vital demographic for Barack Obama given the challenge by Hillary Clinton. Obama’s message was, in fact, the same as in the full text of the attacked comments, although the tone and venue of her comments, and her physical appearance, were different. Obama’s reframing of patriotism directly spoke back to Republicans, who used “love of country” to separate “us” (White, conservative Americans) from “them” (people of color, feminists, liberals, and other assorted malcontents). The Michelle Obama media blitz reached its peak on June 18, 2008, when she appeared on the daytime talk show The View, described by critic Daphne Brooks as “the kaffeeklatch gossip bowl,”49 as a “guest co-host” for the day. In accordance with the conventions of The View, as co-host, Obama was positioned as an insider member of the “us” of the show and not the “them” of featured guests. The change in venue, from a gender-neutral site of a political speech to a feminized location of women’s television, supported Obama’s transformation from “feminist” to “postfeminist.”

Obama entered The View stage to thunderous applause and a standing ovation from the audience. The View was complicit in the reframe of her image, demonstrating that not all had swallowed the negative media messages circulated by the Republicans. The hosts ranged from friendly (conservative personality Elisabeth Hasselback) to giddy (panel moderator Whoopi Goldberg). Obama’s appearance was drastically different from her February remarks. She wore a sleeveless black-and white floral dress accented with a floral pin on one shoulder, an off-the-rack number that sold out immediately after the show.50 Her jewelry consisted of First Lady appropriate simple pearl earrings and a wedding ring, while her skin, enhanced by bronzer, glowed. Her hair, while still a bob, was bigger, bouncier, and shinier; a bang subtly swooped towards her left eye. Her makeup was vivid and sparkling. Her physical image, of a vibrant fashionista, played in stark contrast to her more muted affect and dressed-down appearance during her February “pride” remarks (Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2. Michelle Obama looking glamorous. Screenshot from “Michelle Obama on The View,” The View, June 18, 2008. Viewed 6 October 2017. www

After quoting the famous line, co-host Barbara Walters asked Obama, “What is your answer to all of these attacks?” to which Obama responded,

Well, you know, I take them in stride. It’s a part of this process. We’re not new to politics. But just let me tell you of course I’m proud of my country. Nowhere but in America could my story be possible.

As opposed to Obama’s February remarks where she deployed some signifiers of postrace, on The View her transformation to highly feminized, postracial subject appeared complete. She used the tropes of girlishness in contrast to her Wisconsin speech: here her sentences were shorter and her tone was more intimate, friendlier, and conversational. Smiles punctuated her statements. This was not a seriously delivered speech, but a perky monologue peppered with interjections from the cohosts.

Obama’s makeover provided a blueprint for how women of color could perform a postracial image transformation. Although Hortense Spillers wrote with “dismay” how Obama “had to be rechoreographed into a more palatable routine;.… ‘handled,’ ‘softened’ in tone and image,”51 I respectfully disagree that her makeover was cause for alarm and that she herself wasn’t a co-conspirator. Indeed, Obama’s strategically ambiguous resistance remained constant even while she performed as a postracial subject. A White woman telling this story (such as Hillary Clinton or Sarah Palin) iterated a normative American rags-to-riches narrative; the intersectionality of a Black woman telling presented a critique of racist assumptions of African American success.

Obama continued, calling herself “a girl” twice in quick succession: “I’m a girl that grew up [Barbara Walters: Give people a little bit] I’m a girl that grew up on the South Side of Chicago.” In this media appearance, Obama spoke, for the most part, on personal, individual matters and not collective ones. In utilizing the tropes of postrace, Obama named her Blackness through the code “the South Side of Chicago,” which, like in the first speech, was meant to connote both Black and working class. But here it is not used alongside a conjuring of an “Iowa farmer” to foster interracial, working-class unity, a possible allusion to cultural miscegenation or shared oppression, but to signify the point from which she departed, the place she moved beyond. The South Side of Chicago became the place Michelle Obama made it out of and not a place in which people currently reside. Obama also brought together her intersectional identity here by describing herself as “Black girl from the South Side of Chicago.”

She continued,

My father was a working-class guy who worked a shift all his life. And because of his hard work he sent not just me but my brother to Princeton [BW: he’s now the coach]. He’s now the coach of Oregon State. Go Beavers! I tell people just imagine the pride that my parents, who didn’t go to college, felt. That they could through their own hard work and sacrifice have us achieve things that they could never imagine. And so I am proud of my country without a doubt. I think when I talked about it in my speech I think what I was talking about was having pride in the political process.

Obama employed the language of postrace by using no racialized descriptor, in code or otherwise, for her father, as he was a “working-class guy.” She used the language of meritocracy, another element of postrace, where “hard work and sacrifice” trumped structural, institutional, and historic discrimination and provided entrance to the elite, of which the Ivy League and Princeton University were the ultimate signifiers. Michelle Obama’s utilization of postracial tropes, her strategic ambiguity, was necessary for her voice to be heard by the mainstream of the country.

However, focusing on Black success was far from just a pander to postrace. As part of her redefinition of Americanness, Obama paused on her parents’ “hard work and sacrifice”—two ideas that might sound like conservatively tinged—“all American notions,” but which resonated quite differently in lieu of the anti-Black racism in which African Americans have been historically and contemporarily pathologized. In such a context, Obama’s comments resounded far differently than Joe Biden’s recounting of his kitchen-table chats with his working-class father, Hillary Clinton’s recalling her down-home roots in Scranton, or Sarah Palin’s many significations of her “real” American identity. The race and gender of the speaker cannot be dismissed. Even though her rhetoric did not necessarily sound remarkably different from Biden, Clinton, or Palin here, the context of the racist and sexist nature of the previous attacks on Michelle Obama made her remarks extremely different. She was negotiating racist, misogynistic postracial culture and must respond in a safe, mainstream, and recognizable (read: White-friendly) manner: with strategic ambiguity. Yet Obama did not abandon a vision of collectivities, as she finished her remarks,

People are just engaged in this election in a way that we haven’t seen in a long time and I think that everybody has agreed with that, that people are focused [Joy Behar: they’re coming out]. They’re coming out.

Obama narrated her own family as classically American and reframed pride and patriotism as not merely the purview of White, conservative Americans. On The View, Michelle Obama worked to create a space in which she could reclaim her own humanity by presenting herself as having common goals with the White mainstream of the country. In a similar vein, the popular media obsessed over her self-applied moniker of “mom in chief,” a major part of this new Michelle Obama effort. But I do not think of this as pandering, as her harsher critics did. Michelle Obama’s appearance on The View, where she performed some signifiers of postrace, could not be dismissed as only postracial. Instead, Michelle Obama’s reframing must be seen in the context of a material history in which African American women have never had the luxury to be the most esteemed “lady” in the world. Indeed, a Black woman naming and claiming motherhood through the cutesy phrase “mom-in-chief” must also be seen in the historical context whereby Black women did not have the luxury of being stay-at-home mothers. This material history is reflected not merely in representation but also in areas of life as differential as income and mortality; in 2016, the median income of Black households was almost half of the median income of White households and, in 2014, infants born to Black mothers perished at more than twice the rate of infants born to White mothers.52

By recognizing this material history and taking it into account, we then understand why Obama’s “playful” words are actually resistant. We could not read Obama’s words as resistant if we were to look at them only in terms of race or only in terms of gender, as feminist philosopher Maria Lugones explains: “the logic of categorical separation distorts what exists at the intersection … [T]he intersection misconstrues women of color.”53 Reading Michelle Obama at the intersection enables an understanding of her use of, and resistance to, postrace—her strategic ambiguity. Black women’s claims to humanity using the language of mainstream goals is radical given the long history, and continued present, of dehumanizing Black women. Michelle Obama’s public statements illustrate that she is a Black woman voicing a collective rehumanization that is so powerful for some and so vexing for others. The key visual marker makes the difference in The View event as opposed to the February stump speech. Visually marked as feminist, she could not use postracial framing to resistively insert a critique of postracial assumptions about meritocracy; visually marked as hyper-feminized, she offers much of the same content without the backlash. Obama’s visual code of a stylistic mask allows her to get away with such resistant content. Strategic ambiguity is successful when it comes with matched set of look and message.

From Postracial Performance to Postracial Resistance

The conventional media coverage stated that Michelle Obama went from being almost universally hated because of her unveiled racial animosity (e.g., being dubbed Mrs. Grievance on the cover of the National Review;54 to being almost universally adored because of her accessibility (e.g., topping People Magazine’s “best dressed” list).55 I have argued here that this mediated “makeover” is achieved by her strategic ambiguity: deploying less-coded to more-coded ideologies of postrace. Her “makeover” is achieved by her performance of visual and linguistic postracial codes in the second event. Michelle Obama’s presentation of her accessible fashionista View-self matches the highly feminized, postracial tools she used, even while she continued to offer content that subverted the racism and misogyny that remains even in our purportedly postracial nation.

For Obama, majority–minority settings provided a safe space to name systemic and discursive racialized and gendered inequality. For example, at a 2009 campaign fundraising event with prominent African Americans, Obama used “our” and “us” to refer to African Americans, stating: “I am committed, as well as my husband, to ensuring that more kids like us and kids around this country, regardless of their race, their income, their status, the property values in their neighborhoods, get access to an outstanding education.”56 To this same group, she stated: “I know that the life I’m living is still out of the reach of too many women. Too many little Black girls. I don’t have to tell you this. We know the disparities that exist across this country, in our schools, in our hospitals, at our jobs and on our streets.”57 When she became First Lady, Obama presided over a ceremony at which a bronze bust of Sojourner Truth was unveiled. There she stated: “Now many young boys and girls like my own daughters will come to Emancipation Hall and see the face of a woman who looks like them.” She told the gathering: “I hope that Sojourner Truth would be proud to see me, a descendant of slaves, serving as the First Lady of the United States of America.” Such frank language illustrated that Obama saw herself as a racialized, gendered member of a larger African American community in a racist, sexist world. These statements demonstrated a clear challenge to postrace that was appropriate for the occasion and the audience. Obama crafted a public identity that allowed her to slip in critiques of the inequality still embedded in our nation, while still garnering fans who might object to such critiques if they were made explicit.

Thus, as First Lady, Michelle Obama reframed and redefined traditional ideologies in the service of refuting racism and sexism. She refused to let her body be used against her community. She resisted postrace through what Chela Sandoval calls differential consciousness, a strategy in women of color feminism “of oppositional ideology that functions on an altogether different register … Differential consciousness is the expression of the new subject position called for by Althusser—it permits functioning within, yet beyond, the demands of dominant ideology.”58 Sandoval sees women of color differential consciousness as a type of “differential praxis,” a theory that operates through real-life practice as decolonial strategy.

Obama’s strategic ambiguity can continue to be evaluated as resistant in a variety of ways. She used racialized and gendered euphemisms as a rhetorical strategy, for example, in the way that rhetorician Edward Schiappa describes the manner in which euphemisms are used to domesticate an otherwise fearful nuclear arsenal for an American public.59 Michelle Obama’s careful choice of terms could be considered a euphemism that domesticated an otherwise fearful racial arsenal for the American public. Obama’s coded language could also be an attempt at resistant passing, akin to the queer rhetorics analyzed by critical rhetorician Charles E. Morris III. Performing euphemisms as rhetorical strategy and passing through coding herself as (an exceptionally glamorous) “everymom” has the effect of winking at the insider audience (of women of color) while fostering acceptance and even adoration from the outsider audience (of White women). The surge of positive feelings toward the United States’ first African American First-Lady-to-be bucked a culture that still frequently reviled African American women.

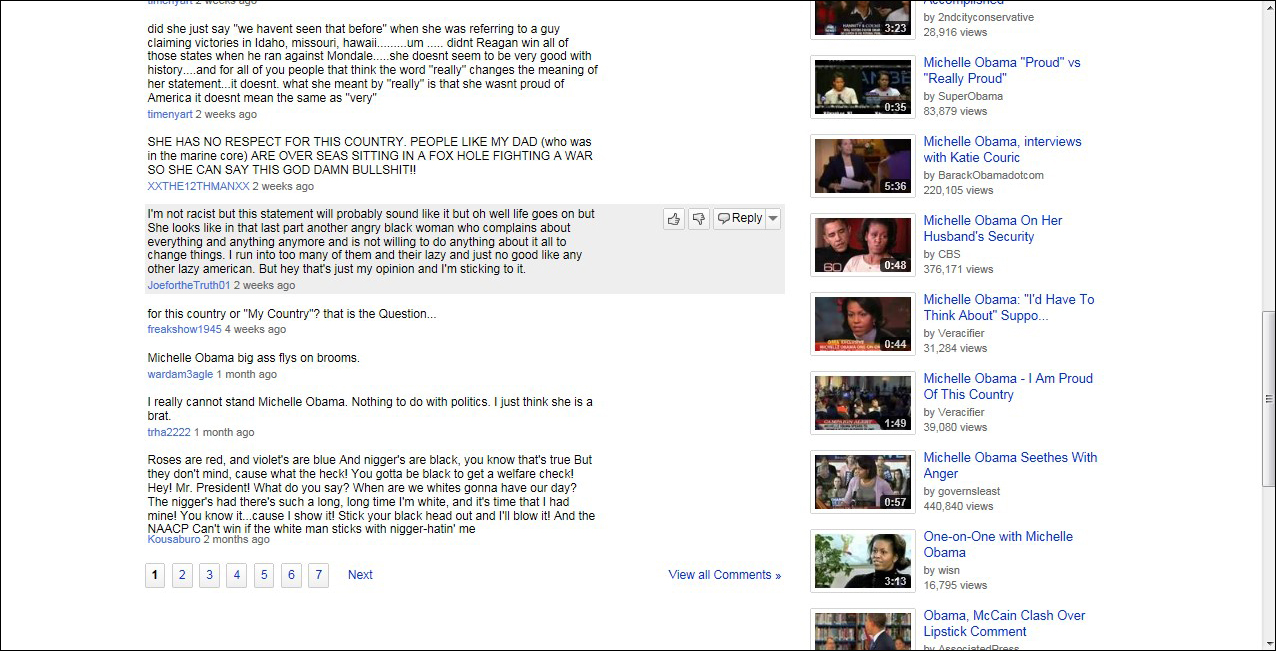

In her public statements speaking back to verbal attacks, Obama performed strategic ambiguity, deploying its very tenets by speaking about race, class, and gender in code, and by reframing and redefining ideas such as American and patriotism. I want to be clear that all of the American public did not meet Obama’s performance on The View with the thunderous applause of that studio audience. In fact, for a number of years I have followed the comments that are posted online below clips of her View appearance, and they are almost always chock-full of hate. The cropped screen shot in Figure 1.3 from 2011 demonstrates just one moment of one day of such hatred. From the nearly all caps entry, second in the image, that decried Michelle Obama’s alleged lack of “RESPECT FOR THIS COUNTRY” as “GOD DAMN BULLSHIT,” to the “poem,” last in the image, that ends with the threat—“Stick your black head out and I’ll blow it [off]!”—the anti-Black racism knew no bounds. In anonymous online commentaries, as in other mediated spaces, our Ivy League-educated First Lady/First-Lady-to-be experienced what critic Natasha Gordon-Chimpembere calls a “metaphorical lynching.”60

Figure 1.3. A sampling of anonymous hatred towards Michelle Obama online. Screenshot from comments underneath YouTube clip “Michelle Obama Clarifies ‘Proud’ Remark.” Viewed May 13, 2011. www

I also want to be clear that this moment on The View happened alongside many other similar moments, from her gracing a vast array of magazine covers to her celebrated remarks at the 2008 Democratic National Convention (DNC). At that convention, as critic Caroline Brown notes, Obama combined “God and motherhood, national pride and a devotion to the military” in a successful speech that “struck a chord that has resonated with the American public.”61 Critical race scholar Verna Williams notes that Michelle Obama opened the convention by affirming, “I stand at the crosscurrents … of history”—not her husband, not Hillary Clinton, but Michelle Obama.62 At that speech, as on The View, Obama’s discussions of race had to remain coded. After 2008, Obama enjoyed much praise as First Lady.

In her 2016 DNC convention speech, Michelle Obama emerged again as the star. Wearing a cap-sleeved, fitted dress with sweetheart seaming that could only be described as deep Democrat blue, Obama’s grace and poise ruled the stage. With the platform adorned in a similar blue, Obama became the physical embodiment of the 2016 Democratic party. Her hair dusted her shoulders, her bangs swooped over one eye, and her earrings appeared to be the marriage of hoops and pearls; her skin glowed while her beautifully lined eyes glimmered, and her words emerged from lips shining with a neutral color. Obama began her speech by broadly narrating the family’s entrance into the White House as one of concern for their daughters. She named Trump in code, iterating the family response to negativity: “When they go low, we go high” (Figure 1.4). Continuing broadly—her speech punctuated at times by audience yells of “We love you, Michelle!”—Obama said “we know that our words and actions matter,” before moving on to racial specificity. Such words mattered for all, yes, but especially for “Kids like the little Black boy who looked up at my husband, his eyes wide with hope and he wondered ‘is my hair like yours?’”

Obama continued, “the story of this country,” the one that “brought me to the stage tonight,” was one of “generations of people that felt the lash of bondage, the shame of servitude, the sting of segregation.” The next part of the speech went viral: “I wake up every morning in a house that was built by slaves.” She paused with assurance for thunderous applause. Her eyes appeared to be slightly welling up with tears as she continued, “I watch my daughters [touched her chest], two beautiful, intelligent Black young women, playing with their dogs on the White House lawn.” This statement was capped off by more roaring approval from the crowd. Obama refuted postrace by underscoring her daughters’ race and gender, calling the teens, in a feminist manner, “young women” (and not girls). In this moment, Michelle Obama’s movement from postracial resistance through strategic ambiguity to Black feminist resistance through forthright critique was complete.

Figure 1.4. Michelle Obama rousing the crowd at the 2016 DNC. Digital image. Getty Images. July 25, 2016. www

In this chapter, taking Michelle Obama’s lead, I have used women of color theorizing to unpack her comments at a rally and read them against her later reframing on The View, to show that strategic ambiguity enabled her shift in popularity. Michelle Obama’s sophisticated strategic ambiguity, how she spoke back to postracial ideology, helps minoritized twenty-first century subjects understand how power, privilege, racialized and gendered discrimination, and resistance function in our present moment. She showed us when we can speak through code and when we can abandon code as we take our seats at the table. As the next chapter will show, not all Black women celebrities, including the Queen of All Media Oprah Winfrey, were able to perform strategic ambiguity as successfully and seamlessly as our former First Lady.