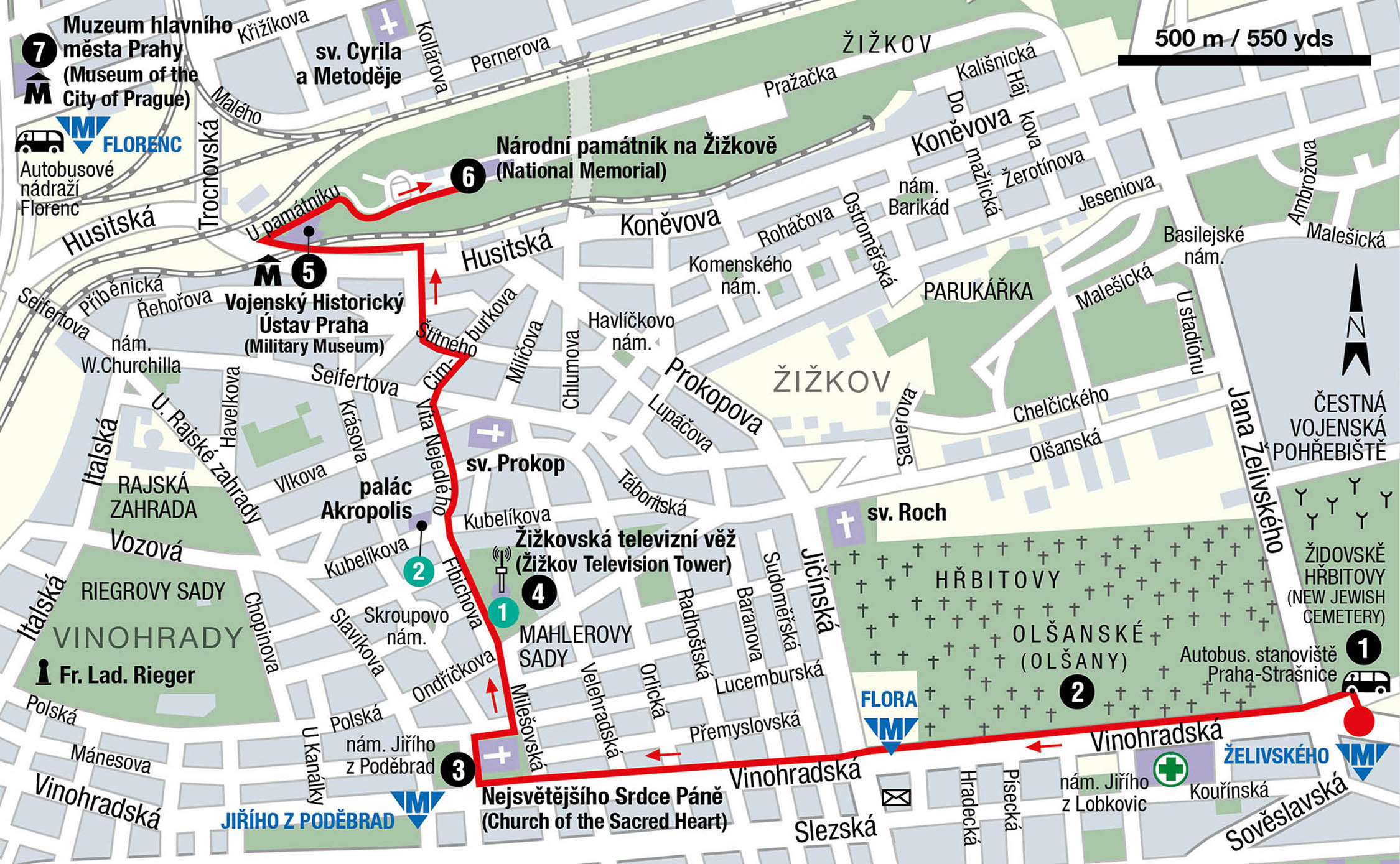

DISTANCE: 5km (3 miles)

TIME: A full day

START: New Jewish Cemetery

END: Museum of the City of Prague

POINTS TO NOTE: The first part of this route is best taken by public transport – it would turn into quite a trek otherwise. Buy a 24-hour ticket that allows you to use the metro and trams for a whole day.

This route explores two of Prague’s more interesting outer districts, the first the sometimes down-at-heel district of apartment blocks that is Žižkov (also known as Prague 3). Its working-class credentials are well established and it was at one time a hotbed of sedition. It is also famous for a huge number of local pubs (more than any other district of Prague), not all of which are welcoming or salubrious. The neighbouring district of Vinohrady gets its name from the vineyards that once thrived here. Today, in contrast to Žižkov, it is rather bourgeois, pleasant, and lively – full of young, upwardly mobile Czechs, who live in the fin-de-siècle apartment blocks that make up much of the area.

Franz Kafka’s grave in the New Jewish Cemetery

Shutterstock

Žižkov’s Cemeteries

Begin at the far-flung end of Žižkov by the New Jewish Cemetery 1 [map] (Židovské Hřbitovy; www.synagogue.cz; Mon–Thu and Sun Apr–Sept 9am–5pm, Oct–Mar 9am–4pm, Fri 9am–2pm all year; male visitors must wear yarmulkes, skull caps, available from the gatehouse; free). The cemetery is easily reached by metro, alighting at Želivského station, or take the tram (Nos 10, 11, 16 and 26 all stop here). It is a serene and atmospheric spot with attractive, tree-lined avenues of graves overgrown with ivy. Looking at the headstones you realise just how wealthy and important the local Jewish community was before World War II. It included owners of industry, doctors and lawyers, and, ironically, many were German-speakers (most of the inscriptions are in either Hebrew or German).

Many people visit to see the grave of Franz Kafka, usually covered in flowers and notes (follow the signs leading to block 21). However, the plain Cubist headstone is not the most impressive; look instead for the striking Art Nouveau peacock on the headstone of painter Max Horb (in block 19).

Church of the Sacred Heart

Rod Purcell/Apa Publications

Olšany Cemetery

Leave the New Jewish Cemetery and take either the metro to Flóra station, or tram 10, 11 or 16 to the stop of the same name. Here you will find the second of Žižkov’s large cemeteries, Olšany 2 [map] (Hřbitov Olšanske; May–Sept 8am–7pm, Mar–Apr, Oct 8am–6pm, Nov–Feb 8am–5pm; free). This huge necropolis has been the preferred burial spot of many famous Czechs (particularly if they have not managed to get a spot in Vyšehrad). Wonderfully Gothic in parts, it has higgledy piggledy graves, all slightly overgrown. Among the famous Czechs buried here are painter Josef Mánes (1784–1843), Art Nouveau Symbolist sculptor František Bílek (1872–1941) and painter and writer Josef Lada (1887–1957).

However, perhaps the most venerated grave is that of Jan Palach (1948–69), who committed suicide in political protest in 1969 and whose body was moved here in 1990. Palach is buried near the main entrance on Vinohradská. Also here is what must be one of the most overblown funerary monuments, that of Rodina Hrdličkova: a sculptural group with a woman pleading with a man in uniform not to follow an angel up to heaven.

Prague Television Tower

Shutterstock

Church of the Sacred Heart

Time to get back on public transport, this time to Jiříhoz Poděbrad by metro or on the tram (again Nos 10, 11 or 16). On the square of the same name as the metro station is the most unusual Modernist building to be found in Prague, the Church of the Sacred Heart 3 [map] (Nejsvětějšího Srdce Páně; www.srdcepane.cz; only open 40 mins before and 30 mins after mass, Mon–Sat 8am, 6pm, Sun 9am, 11am, 6pm; free). Designed by the architect Josip Plečnik (who was responsible for the restoration of St Vitus), it was built in 1932 in an eclectic style, which looks forward to the later developments of postmodernism. The monolithic structure uses elements of Classical and Egyptian styles on a rather uncompromising exterior, and is impressive but not immediately appealing. However, it is enlivened by the huge glass clock on the narrow tower flanked by obelisks.

Unlike the forbidding facade, the interior is high and spacious with a coffered ceiling. The clock tower is climbed via a ramp that is double-sided so that the light streams through from one side of the tower to the other; peering out through the glass faces gives a spectacular view over the city.

Close-up of the ‘babies’ on the Television Tower

Shutterstock

Television Tower

Retrace your steps to the square and this time continue on foot, taking Milešovská at the northeast corner. This leads to Mahlerovy sady (Mahler Park) where, dominating the entire district and much of the city, is the Žižkov Television Tower 4 [map] (Žižkovska televizní věž; www.towerpark.cz; daily 8am–midnight). At 216 metres (708ft) and with a boldly modern (almost science-fiction-inspired) design based on three interlocked towers, this is the most adventurous piece of architecture (by Václav Aulický and Jiří Kozák) of the Communist era. Inspired by the similar tower on Alexanderplatz in Berlin, in an unpopular move it was built on the site of an old Jewish cemetery (used between 1786 and 1890). It is the tallest building in Prague.

Work began on construction in 1985, and the finishing touches were only made in 1991 after the fall of the Communist regime; before then it had allegedly been used for blocking foreign broadcasts from the West. Since then the tower has acquired a number of rather alien babies crawling up the steel tubes, courtesy of David Černý.

It is possible to take the lift up to the Observatory at 93 metres (305ft), from where there is an awe-inspiring view over the entire city with telescopes provided. After a major renovation there are now three cabins, each with a different theme and unique perspective of the city, plus a room to view a film of the history of the tower. For dining in the sky the Oblaca Restaurant and café offers some tremendous views, see 1.

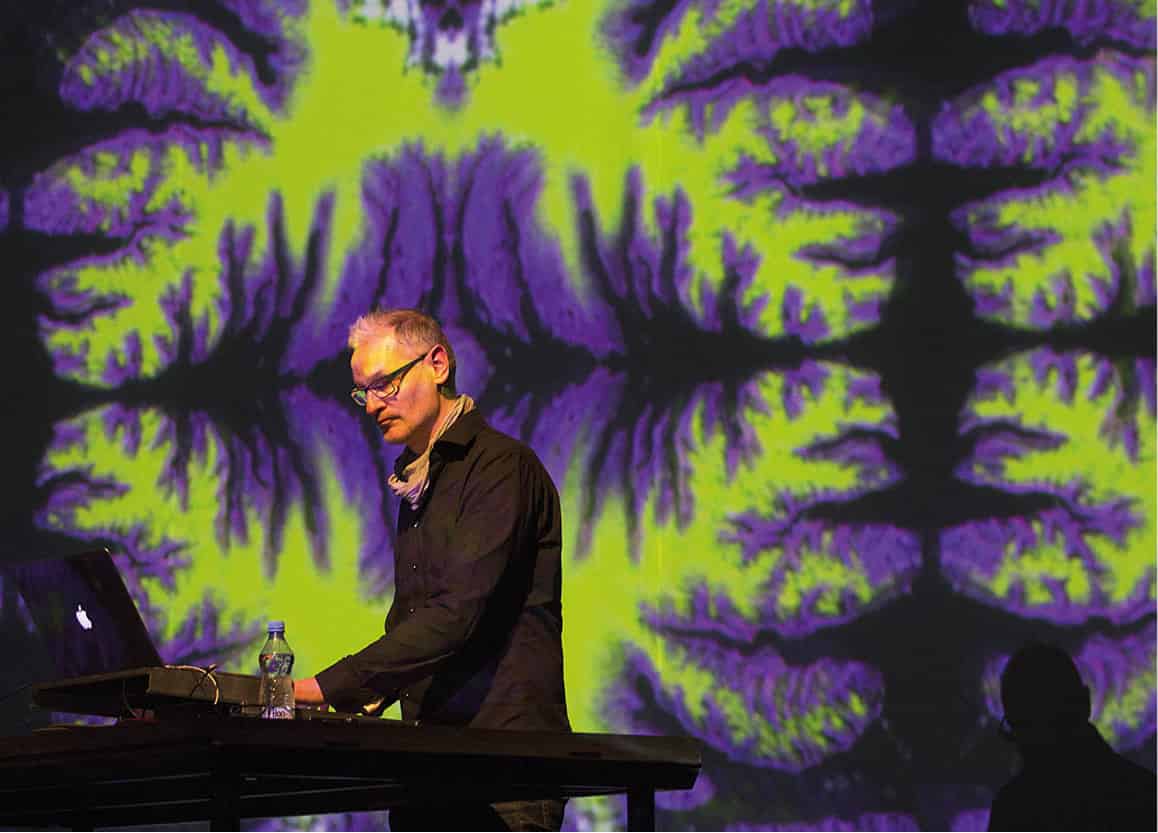

Acropolis Palace

Easily visible from the tower (looking north) is a colourful apartment block on the nearby corner of Kubelíkova and Víta nejedléno. This is the Acropolis Palace (palác Akropolis; www.palacakropolis.cz; box office Mon–Fri 10am–midnight, Sat–Sun 4pm–midnight), an arts centre set in the pre-war Akropolis theatre. The centre has a concert hall, cinema, theatre and exhibition space. Notable for putting on an eclectic selection of groups and acts, especially world music performers, this is one of Prague’s more exciting music venues. Be sure not to miss the wonderfully designed bar and restaurant either: see 2.

The Acropolis Palace hosts an eclectic programme

Shutterstock

Žižkov Hill

Make your way down the hill taking Víta nejedléno and Cimburkovo, turn left into Štítného and then go down Jeronýmova on to the main road of Husitská. Turn left, cross the road and just before you reach the railway bridge take the cobbled road U památníku on the right.

Military Museum

On the way up the hill you will pass the Military Museum 5 [map] (Vojenský Historický Ústav Praha; U Památníku 2; www.vhu.cz; Tue–Sun 10am–6pm; free), which is rather more interesting than first impressions might suggest. The exhibits tell the story of the Czechoslovak Army from its inception in 1918 up to World War II and, apart from an impressive collection of headgear, there are good displays on World Wars I and II.

National Memorial doors

Shutterstock

National Memorial

Keep on climbing through the wooded park and you will come to a series of steps that lead up Vítkov Hill to a wide esplanade. Here you will find the National Memorial 6 [map] (Národní památník; www.nm.cz; Wed–Sun 10am–6pm), an immense granite-faced cube containing the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier.

Right in front of it stands one of the biggest equestrian statues in the world, the monument to the Hussite leader Jan Žižka. The enormous equestrian statue (given greater height by being placed on a granite platform), by the Czech sculptor Bohumil Kafka (1878–1942), was commissioned after a competition in 1925 (one of a series that had created bad feeling and controversy about how to commemorate Žižka’s victory). Only the Stalin monument, which had dominated Letná Hill until it was demolished in 1963, was bigger than that of Žižka.

The granite monolith of the National Memorial itself was initially designed by Jan Zázvorka and built in 1929–30. However, after World War II the building was redesigned and used as both the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier and as a final resting place of worthies of the Communist Party, including Klement Gottwald, whose body was preserved in a similar way to that of Lenin in Red Square in Moscow. Gottwald is now in Olšany Cemetery (for more information, click here). Although it is not possible to gain access at present, the legacy of the Communist redesign can be seen in the numerous reliefs and statues of heroic workers and revolutionary soldiers that adorn the bronze doors.

The complex now has an air of slight neglect, and there are few other places in Prague where the ghost of the Communist years can be felt so easily. However, the walk up through the park is pleasant and the views from the top of the hill are wonderful.

To get back into town, retrace your steps down the hill and turn left into Husitská. At the first bus stop you come to (on U památníku), catch either the No. 175 to Florenc, or No. 133 to Staroměstská.

Statue of Jan Žižkov at the National Memorial

Shutterstock

City of Prague Museum

Those who still have some energy left should alight at Florenc and make their way to Na Poříčí 51 and the Museum of the City of Prague 7 [map] (Muzeum hlavního města Prahy; tel: 224 816 772; www.muzeumprahy.cz; Tue–Sun 9am–6pm), a fascinating collection housed in an imposing building. Much of the labelling is in Czech only, so ask to borrow the English booklet from the front desk.

The collection

The galleries take you through the history of the city in great depth, from prehistory and the medieval period on the ground floor, to the Renaissance and Baroque upstairs. The museum’s prize exhibit is undoubtably Antonín Langweil’s enormous paper model of the city (1837). Also here is the architect Josef Mánes’s original design for the astrological face of the Old Town Hall.

Food and Drink

1 Oblaca Restaurant

Malhlerovy Sady 1; tel: 210 320 086; www.towerpark.cz; daily 8am–midnight; €€€

A sleek modern restaurant some 66m (216ft) above the ground in the Žižkov Television Tower, which serves modern cuisine using local seasonal ingredients. There are great views to accompany dishes such as saddle of suckling pig and fillet of Czech trout. It’s expensive but there is also a café serving lighter snacks.

2 Palác Akropolis Restaurace

Kubelíkova 1548/27; tel: 296 330 990; Mon–Thu 11am–12.30am, Fri–Sun 11am–1.30am; €

The food is simple but tasty, and you can drink here till late, but the surreal decor is the real star. Created by artist František Skála, it features an aquarium full of bizarre objects and even an upside-down canoe.