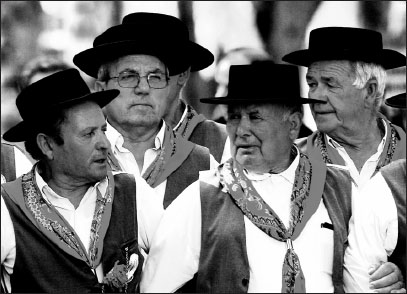

The word “típico” is widely used and highly regarded in the Portuguese language. Translated literally as “typical,” típico means anything traditionally, truly, typically Portuguese. There is typical everything: dishes, restaurants, customs, costumes, songs, dances… and these can vary from region to region or even town to town. These traditions have been cherished and maintained throughout the country’s history and are proudly displayed during holidays and local festivals as an integral part of Portuguese culture.

Portugal has fourteen public holidays throughout the year plus over a hundred municipal holidays. The national holidays celebrate either a religious or historical event, while the municipal celebrations usually honor the town’s patron saint, with one day taken off work and local festivities that can last a week or more. When a holiday’s date falls on a Thursday or Tuesday, it is common to take the Friday or Monday off (“fazer ponte”—“make a bridge”) and extend the holiday to form a long weekend.

Christmas and Easter are the most important religious holidays. Extended families use the occasion to get together, going to mass and sharing lavish meals of traditional food and plenty of wine.

Midnight mass (missa do galo) is attended on Christmas Eve (unofficially also a holiday, except for retail businesses), usually followed by a ceia or evening meal. On December 25 the festivities continue with lunch and often dinner as well. The menus vary from region to region, but Christmas meals are typically comprised of cod-based dishes as well as the traditional roast turkey, with rich desserts and pastries heavy in butter and sugary egg yolks. It is normal for families to travel around a lot during these two days in an attempt to see as many relatives as possible, and gifts are exchanged at each meeting. At this time of year, town and city centers are filled with lights, nativity scenes, and other traditional Christmas decorations. Most homes have a Christmas tree and nativity scene (Presépio) with Joseph, Mary, and Jesus in the manger, as well as figurines of shepherds, animals, and the three wise men. The more modern figure of Santa Claus has permeated the once strictly religious holiday and is also included in the public and private decorations and festivities.

January 1 New Year’s Day

February (always a Tuesday) Carnival

March/April Good Friday

March/April Easter Sunday

April 25 Liberation Day

May 1 Labor Day

May/June Corpus Christi

June 10 Portuguese National Day

August 15 Assumption Day

October 5 Proclamation of the Republic

November 1 All Saints Day

December 1 Restoration of Independence

December 8 Immaculate Conception

December 25 Christmas

Palm Sunday, one week before Easter Sunday, marks the beginning of Holy Week (Semana Santa). Customs vary from town to town and region to region, the older neighborhoods and rural areas being more “typical” and maintaining the more traditional ceremonies, but the principal rituals are upheld throughout the country. On Palm Sunday, the last day of Lent, each parish holds a procession celebrating Christ’s entry into Jerusalem. Often the priest takes the opportunity to visit parish homes and families, and it is customary for children to give their godparents flowers. Throughout the week, a variety of processions are carried out parading statues of Jesus and Mary, and people hang their most elaborate and treasured embroidered blankets and cloaks outside their windows and balconies.

Good Friday, the anniversary of Christ’s crucifixion, is a day of fasting and spiritual reflection. There are also local processions and plays that reenact the Passion of Christ. On Easter Sunday, churches are full and a general sense of celebration pervades. As is the case at Christmas, families unite for large, elaborate meals, and the international customs of offering and hunting for chocolate Easter eggs and rabbits are also practiced.

Carnival, or Entrudo, falls on the Tuesday before Ash Wednesday and marks the last day before Lent. Though not an official holiday, schools close on Carnival Monday and Tuesday, and many companies give their employees the day off. The Portuguese celebration of Carnival varies greatly throughout the country. Some cities, such as Loulé, choose to copy the Brazilian concept of carnival, with street dances and samba school competitions, while others prefer putting local craftsmanship on display. In some areas, celebrations are of a more ceremonial and conservative nature, whereas in cities like Ovar or Torres Vedras, participants run loose, tickling and teasing onlookers or parading giant puppets that satirize historical figures and modern-day politicians. Generally, people use Entrudo as an excuse to dress up and have fun, be it publicly or privately, while others simply take the opportunity to get away and enjoy a long weekend.

The month of June brings what is known as the Santos Populares, festivities of pagan origin celebrating the Summer Solstice. The favorite saints are Santo António (Saint Anthony), São João (Saint John), and São Pedro (Saint Peter), and though the reason these holy figures are associated with the summer folly is unknown, they have come to symbolize the connection between the sacred and the pagan. Between June and August, private and public balconies and patios all over the country are decked with lights, streamers, wild leeks, and potted basil. Communities come together to consume large quantities of grilled sardines, caldo verde (a traditional green cabbage soup), and wine in order to celebrate summer and ask the saints for good luck. The day following the celebrations is a municipal holiday.

Santo António was an exemplary Franciscan monk who was considered among other things to be the protector of the poor and of single girls, and a curer of infertility, the last two attributes endowing him with matchmaking qualities. Though not officially Lisbon’s patron saint, he has been “adopted” by the city, and the festivities that honor him begin on June 12 with the Santo António weddings. Since 1950, the city of Lisbon has selected a group from among the city’s poorer engaged couples to participate in a public wedding. After the ceremony, the couples are paraded around the city, stopping at the saint’s statue to offer him the bride’s bouquet before continuing on to the reception, also provided by the city.

Also taking place that night are Lisbon’s “Marchas Populares.” Avenida da Liberdade, one of downtown Lisbon’s main avenues, sets the stage for a parade where over twenty associations representing the traditional neighborhoods compete in songs, choreography, and costumes. Each procession is an explosion of color and music that attempts to capture the essence of local tradition.

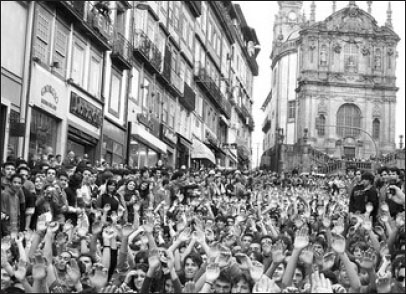

In the north, the preferred saint is São João. As in the rest of the country, outdoor fairs and parties are organized where plenty of traditional singing and dancing takes place, with the night of São João being celebrated on June 23. In Porto, revelers roam the streets and squares armed with plastic hammers and wild leeks, banging them on the heads of passersby for good luck. It is best to maintain a sense of humor and take this behavior in the spirit of excess and good fun! Aside from the neighborhoods competing with their displays of fireworks, it is also customary on this night for everyone to set large, colorful paper balloons alight and release them into the sky, watching them float, glowing, over the city.

In the urban centers today family occasions are celebrated or marked in much the same way as in other cultures with Christian practices. Weddings, baptisms, and funerals in Portugal’s small, rural communities, however, follow time-honored traditions.

In traditional Portuguese weddings, the bridal party, consisting of the bride’s extended family and close circle of friends, will go to the bride’s home for breakfast and then accompany her to the church for the wedding ceremony, while the same occurs at the groom’s family home. After the ceremony, the guests are invited to a reception where a lunch consisting of numerous courses and large quantities of wine and other beverages is served. Following lunch and dancing, it is customary for everyone to visit the newlyweds’ home and then go home themselves for a siesta before meeting up again for another meal, usually but not necessarily lighter than the lunch. Sometimes guests are invited back the following day for leftovers! Wedding guests are expected to give the newlyweds a gift. In some cases the bride and groom may have gift registries in shops where people can purchase items they have chosen beforehand, while in others, an envelope is passed around during the reception for guests to give money.

Because baptism is a child’s introduction into the religious community, it is usually performed within the community at regular Sunday mass. Thus it is not uncommon during mass for there to be a number of babies (ranging from two or three to ten) waiting to be christened after the regular service. Baptisms are a smaller affair than weddings, usually restricted to family and close friends, but also involve a large meal afterward. It is also customary to take a gift for the child, usually a piece of silverwork with religious significance, such as a cross pendant or a medallion portraying a saint.

Funerals are solemn affairs that do not involve eating or drinking. A death is usually announced by the family in a local newspaper, along with the time and place of the funeral service for those wishing to pay their respects and attend services. People who want to offer their condolences may do so at the wake before the religious ceremony, and many churches and chapels place an attendance book in the entrance for those wishing to sign, as well as a plate to leave personal cards. Once the service has ended, attendants will follow the casket on foot (if a short distance) or drive to the cemetery for the burial, after which people go their separate ways. Women wear black or white for funerals, while men wear suits and a black tie. One week after the death, a seventh-day mass is held to pray for the deceased and for people once again to offer their condolences and pay their respects.

The precise origins of fado are unclear, but on one point everyone agrees: these quintessentially Portuguese melodies are the true expression of the Portuguese soul. The word “fado” derives from the Latin “fatum,” which means fate. The songs, melancholic lamentations accompanied by the Portuguese guitar, mirror the Portuguese romantic and fatalistic side, describing the pain and saudade of surrendering to one’s destiny.

One theory states that fado descends from Moorish chants, which were also melancholic and doleful. Others suggest that the songs came from the medieval jesters and troubadours who sang about friendship and love as well as criticizing politics and society through satire. The most common explanation, however, is that fado derives from “lundum,” the music sung by Brazilian slaves, and was brought to Lisbon in the mid-nineteenth century by Portuguese sailors. The first known fado songs speak of the sea and distant lands and therefore seem to support this theory.

The Portuguese guitar is one of fado’s main symbols, the other being the black shawl. Men usually sing fado wearing a dark suit, while women are also dressed in dark colors with a black shawl draped over one or both shoulders. Themes usually revolve around the pain of love and/or death, though individual songs can broach any subject from horses and bullfights to politics and patriotism. “Typical” fado is sung in small, dark restaurants and taverns in the older parts of Lisbon such as Alfama and the Bairro Alto, and the artists can be the most unlikely people, even one of the waiters serving tables. Though conversation can flow normally when no one is performing, it is important to keep quiet when someone is singing or the singer and fellow patrons may take offense. Of course, with artists like Amália Rodrigues, Dulce Pontes, and Marisa, fado has reached an international audience and, thanks to the recordings of new artists like Carminho and Ana Moura, can also be enjoyed at home or in a more modern setting.

In Coimbra, the fado tradition took a slightly different direction. Coimbra housed the country’s first university, and young people from Lisbon and Porto would flock there to receive their education, taking along their guitars and their songs and instilling fado in the student community. Little could better impress a young woman than a suitor standing under her window at night serenading her with heart-wrenching songs of unrequited love. Nor could any other music better explain the saudade of leaving behind the best years of one’s youth and the bohemian student life. Thus fado became the official anthem for graduating university students. Toward the end of the academic year, groups of students from universities around the country can still be seen wandering the city streets at night in their thick black cloaks, playing their guitars and singing their serenades.

The ribbon-burning (queima das fitas) tradition carried out by graduating university students, mainly in the north of Portugal, dates back to the mid-nineteenth century. Upon finishing their exams, students would group together by faculty and form a procession from the university to the town or city’s main square, where they would burn the ribbons used to tie their books together. Over the years, this tradition has grown in participation and sophistication, and there is now an official ribbon-burning week in May, with organized activities and festivities.

This week usually begins with a monumental serenade where the academic community comes together to sing fado and other songs. At these concerts, rather than clapping, the students shake their satchels, displaying all their ribbons, which are covered with signatures of professors, colleagues, friends, and family. There is also usually a religious ceremony where the ribbons and satchels are blessed. After this, the week continues with sketches that parody the professors and academic life, processions, and large parties and concerts. In Porto and Coimbra, ribbon-burning week is a major event, with the activities and events usually making the front pages of the newspapers.

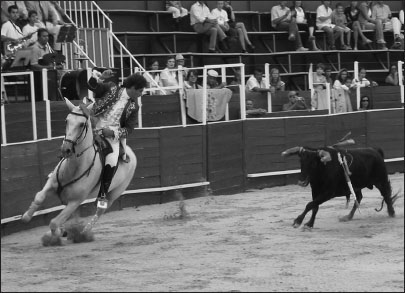

Unlike in Spain, in Portugal the bull is not killed in the ring. At the end of the spectacle it is led out by a herd of cows to be slaughtered for beef.

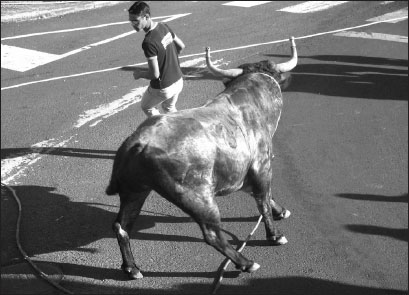

Drawings found in caves throughout the Iberian Peninsula suggest that the ritualistic relationship between man and bull dates back to prehistory. The practice of letting bulls loose among crowds for amusement began during the summer fairs and festivals of the Middle Ages. The art of bullfighting on horseback as it is seen today was developed as entertainment for the aristocracy in the sixteenth century. Later came the practice of bullfighting on foot, which brought the tradition to the masses. Bullfighting in Portugal is of extreme cultural importance; the Portuguese pride themselves on the rituals and traditions of what is considered an art form, and the toureiros (bullfighters) are regarded as heroes for their skill and bravery.

Bullfighting season begins on Easter Sunday and runs through to October. There are corridas (races) or toiradas (bullfights) throughout the country on most weekends, every Thursday night in Lisbon during the summer months, and every day during the weeklong rural fairs that take place in the Ribatejo. The Ribatejo is the region northeast of Lisbon where the bullfighting tradition is strongest and where most of the bulls are bred. In each corrida, six or eight bulls are fought one at a time, with approximately half an hour allocated to each bull. The number of bullfighters varies between one and four, with each bullfighter usually facing two or three bulls. The toureiro performs either on horseback or on foot, never doing both. The toiradas themselves can be only on foot, only on horseback, or a variation of the two.

Bullfights follow a rigid set of rules and the fighters themselves are very superstitious, each with their own personal rituals for preparing for the fight. Once in the ring, the first part of the spectacle involves bullfighters on horseback dominating the bull with lances, while the matadors on foot show their skill leading the bull with a crimson cloak. For corridas on foot, the next phase is for the banderilheiros to face the bull head-on and stick pairs of small spears in its back, ending once again with the matador and his dance with the red cape. With toiradas on horseback, the show is brought to a close with the pega, where a group of eight forcados literally take the bull by the horns and tail and bring it to a standstill with their bare hands. A band plays paso dobles and other traditional bullfighting music to accompany the performance, and there is a trumpeter, who stands and plays certain notes to signal changes in the program. Bullfights are not for the squeamish, but observing the enthusiasm and appreciation shown by the crowd as they applaud, throw flowers, handkerchiefs, and even items of clothing is amusing and exciting entertainment in itself.