Chapter 20

Dendritic Development

Dendrites play a critical role in information processing in the nervous system as substrates for synapse formation and signal integration. Neurons have highly branched, cell type–specific dendritic arbors (or dendritic trees). The size, shape, branching pattern, and position of dendritic arbors are the main determinants of what inputs they receive and how those inputs are integrated. It is now widely recognized that dendrites develop in constant interaction with other neurons and glia. The signals from these other cells affect dendritic arbor development in different spatial domains and time scales. For instance, synaptic inputs may increase calcium influx rapidly and locally to enhance rates of branch addition and stabilization. This dynamic morphological remodeling allows neurons to modify their structure and synaptic connectivity in response to afferent inputs (Cline, 2001; Ruthazer, Akerman, & Cline, 2003; Sin, Haas, Ruthazer, & Cline, 2002). In contrast, calcium signals with slower temporal dynamics may selectively signal to the nucleus to trigger gene transcription (Dolmetsch, Pajvani, Fife, Spotts, & Greenberg, 2001; Kornhauser et al., 2002; Wu, Deisseroth, & Tsien, 2001). Such activity-induced genes can then have profound effects on dendritic arbor structure and function (Cantallops & Cline, 2008; Leslie & Nedivi, 2011; Nedivi, 1999; Nedivi, Wu, & Cline, 1998). Dendrite arbor structure and plasticity are altered under a variety of neurological disorders, including mental retardation (Bagni & Greenough, 2005; Govek et al., 2004; Na & Monteggia, 2011; Newey, Velamoor, Govek, & Van Aelst, 2005) or seizure (Nishimura, Gu, & Swann, 2011), and can be affected by exposure to drugs, including nicotine (Gonzalez, Gharbawie, Whishaw, & Kolb, 2005) and cocaine (Kolb, Gorny, Li, Samaha, & Robinson, 2003; Morrow, Elsworth, & Roth, 2005). The study of dendritic arbor development can therefore provide important insight into the cellular basis of normal brain development, as well as neurological and psychiatric disorders.

After a brief description of dendritic arbor development, we discuss four principles of dendritic development: (1) Transcriptional programs establish rudimentary dendritic morphology characteristic of distinct neuronal subclasses. (2) Extracellular cues interact with signaling pathways to sculpt dendritic morphology. (3) Coordinate sculpting of axonal and dendritic arbors leads to formation of neural circuits optimized for information processing. (4) Electrical and synaptic activity refine dendritic arbor morphology and synaptic connectivity.

Although these principles are general ones, applicable to most if not all parts of the nervous system, we illustrate each one with reference to a model system that has been useful for studying it. Thus, we highlight Drosophila mechanoreceptor neurons for genetic analysis, mammalian cortex for extrinsic signals, vertebrate retina for circuit formation, and Xenopus retinotectal system for activity-dependent structural plasticity.

Dynamics of Dendritic Arbor Development

Dendritic arbor development requires global, arbor-wide architectural modifications (e.g., generalized arbor growth), as well as localized structural changes (e.g., sprouting and retraction of higher order branches). Some changes in dendritic arbor morphology occur rapidly in response to synaptic inputs or growth factors, whereas others occur with some time delay, secondary to new gene transcription and protein turnover.

The advent of in vivo time-lapse imaging has allowed the assessment of cellular events underlying the development of dendritic arbors. In vivo imaging of dendritic arbor development was pioneered in the 1980s by Purves and colleagues, who discovered that peripheral neurons could be imaged repeatedly in developing mice (Hume & Purves, 1981). These studies revealed considerable heterogeneity in the dynamics of dendritic arbor structure and suggested that dendrite structure was affected by differences in afferent inputs to different neurons. More than a decade passed before the methods were developed to reliably label single neurons in the CNS and image their dendrites over time without damage (Wu & Cline, 1998). In vivo time-lapse imaging of neurons is now routine in several systems, including fish, amphibian tadpoles, Drosophila, and rodents, thanks to technical advances in imaging reagents and widespread use of 2-photon microscopy.

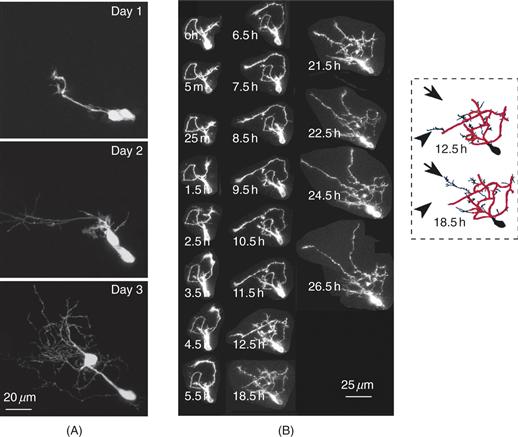

In vivo time-lapse imaging studies of developing optic tectal neurons in Xenopus and Zebrafish and peripheral sensory neurons in Drosophila demonstrate that the dendritic arbors develop through a gradual process in which branches are added and retracted rapidly (Fig. 20.1). Figure 20.1A illustrates the generalized growth of differentiating optic tectal neurons imaged in the intact Xenopus tadpole over three days, and Figure 20.1B shows an optic tectal neuron imaged in vivo over about one day, but at shorter intervals. Widespread changes in dendritic architecture are apparent when time-lapse images are collected over daily intervals or longer, while short interval imaging unveils sites of local branch dynamics and growth that contribute to the changes in structure seen at longer intervals. Many more branches are added to the arbor than are ultimately maintained, so that the net elaboration of the dendritic arbor occurs as a result of the stabilization of a tiny fraction of the newly added branches. These branches then become the substrate for further branch additions. In this way the complex arbor develops gradually as a result of concurrent and iterative branch addition, retraction, stabilization, and extension (Cline, 2001; Hua & Smith, 2004). Time-lapse imaging studies in other systems including rodent hippocampus and cortex, and chick auditory system (Dailey & Smith, 1996; Sorensen & Rubel, 2006) indicate that this plan is fundamental to dendrite development.

Figure 20.1 Time-lapse images of Xenopus optic tectal neurons collected in vivo. (A) This example shows two neighboring, newly differentiated neurons, close to the proliferative zone, imaged over a period of 3 days. These cells initially present glial-like morphologies (day 1). By the next day, these cells have elaborated complex dendritic arbors (day 2), which continue to grow to the end of imaging period (day 3). (B) Example showing an optic tectal interneuron imaged at short intervals over about 1 day. Dendritic trees develop as neurons differentiate within the tectum. Although portions of the dendritic arbor are stable over time (red outlined skeleton at 12.5 h and 18.5 h), other areas are very dynamic as dendritic branches are both added (arrows) and retracted (arrowheads) over time (in this case between 12.5 h and 18.5 h).

Transcriptional Control of Dendrite Development

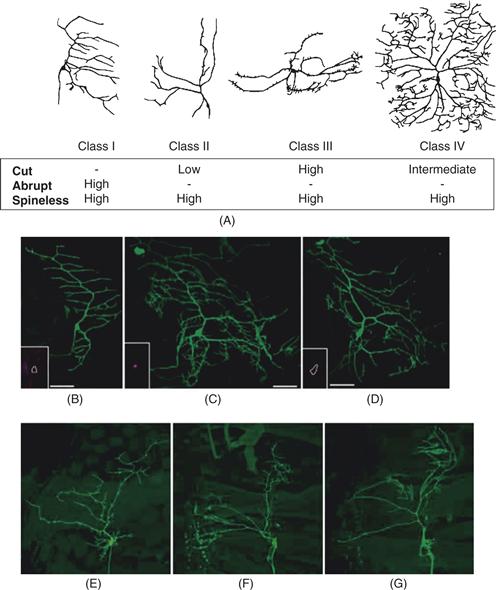

Studies using Drosophila genetics have been instrumental in the identification of core transcriptional programs that control dendrite development. The dendritic arborization (da) neurons, a group of Drosophila sensory neurons with a stereotyped dendritic branching pattern, have provided a useful assay system for the genetic dissection of dendrite development (Gao, Brenman, Jan, & Jan, 1999; Grueber, Jan, & Jan, 2002; Jan & Jan, 2010). Each hemi-segment of the abdomen of the Drosophila embryo or larva has 15 da neurons that can be subdivided into four classes based on their stereotyped location and unique dendritic branching pattern (Fig. 20.2) (Grueber, Jan, & Jan, 2002; Grueber, Ye, Moore, Jan, & Jan, 2003b). Class I and II have relatively simple dendritic branching patterns and small dendritic fields, whereas class III and IV neurons have more complex dendritic branching patterns and large dendritic fields.

Figure 20.2 Transcription factors regulate the diversity and complexity of dendrites. (A) Dendrite morphologies of representative class I, II, III, and IV dendritic arborization (da) sensory neurons in the Drosophila PNS and a summary of the relative levels of expression of the transcription factors Cut, Abrupt, and Spineless in these neurons. (B–D). Ectopic expression of cut increases the dendritic complexity of class I da neurons. (B) Wild-type dendritic morphology of the ventral class I neuron vpda. Cut is normally not expressed in vpda (inset). (C) Ectopic expression of Cut in vpda leads to extensive dendritic outgrowth and branching. (D) Ectopic expression of CCAAT-displacement protein (CDP), a human homolog of Drosophila cut, also induces overbranching. (E–G) Loss of spineless function leads to a dramatic reduction in the dendritic diversity of different classes of da neurons. In loss-of-function spineless mutants, class I (E), class II (F), and class III (G) da neurons begin to resemble one another.

From Parrish et al. (2007b).

Transcription Factors Regulate Cell Type–Specific Dendritic Morphology

Expression of the gene cut in da neurons differs such that neurons with small and simple dendritic arbors either do not express Cut (class I neurons) or express low levels of Cut (class II), whereas neurons with more complex dendritic branching patterns and larger dendritic fields (class III and IV) express higher levels of Cut. Analysis of loss-of-function mutations and class-specific overexpression of Cut demonstrated that the level of Cut expression controls the distinct, class-specific patterns of dendritic branching (Grueber, Jan, & Jan, 2003a). Loss of Cut reduced dendrite growth and class-specific terminal branching and converted class III and IV neurons to class I and II morphologies with simpler dendritic branching patterns and smaller dendritic fields. Conversely, overexpression of Cut in neurons that express lower levels of endogenous Cut transformed branch morphology toward that seen in high-Cut expressing neurons. Furthermore, a human Cut homologue, CDP, can substitute for Drosophila Cut in promoting the dendritic morphology of high-Cut neurons (Fig. 20.2). Thus, Cut may function as an evolutionarily conserved regulator of neuronal-type specific dendrite morphologies.

Class III and class IV da neuron dendrites are made distinct by different combinations of Cut and another transcriptions factor Knot/Collier, which is expressed in Class IV but not in other classes of da neurons. In Class IV da neurons, Knot/Collier suppresses the tendency of Cut to induce actin-rich dendrite protrusions known as “dendritic spikes,” structures unique to Class III da neurons. In contrast, Class III da neurons express high levels of Cut but not Knot/Collier—a combination that favors the formation of dendritic spikes. Thus, Knot/Collier and Cut provide an example of a combinatorial mechanism for specifying neuronal type–specific dendrite morphology (Jinushi-Nakao et al., 2007).

In contrast to Cut, Spineless (ss), the Drosophila homologue of the mammalian dioxin receptor, is expressed at similar levels in all da neurons. In ss mutants, different classes of da neurons elaborate dendrites with similar branch numbers and complexities (Fig. 20.2), suggesting that da neurons might reside in a common “ground state” in the absence of ss function. Studies of the epistatic relationship between Cut and Spineless indicate that these transcription factors likely are acting in independent pathways to regulate morphogenesis of da neuron dendrites (Kim, Jan, & Jan, 2006). A comprehensive analysis of transcription factors with RNAi screens has revealed more than 70 transcription factors regulate dendritic arbor development of class I neurons in Drosophila. These findings suggest that complicated networks of transcriptional regulators likely regulate neuron-specific dendritic arborization patterns (Parrish, Emoto, Kim, & Jan, 2007b).

The Maintenance of Dendritic Fields

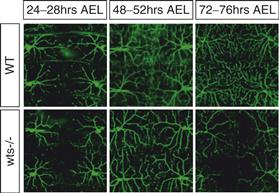

Dendrite development is a dynamic process involving both growth and retraction. Thus, selective stabilization or destabilization of branches might be one important mechanism to shape dendritic arbors. Studies of Drosophila class IV da neurons revealed that dendritic fields are actively maintained and there is a genetic program to maintain dendritic fields. The tumor suppressor Warts (Wts), as well as the Polycomb group of genes are required for the maintenance of the class IV da dendrites.

Drosophila has two NDR (nuclear Dbf2-related) families of kinase: Trc and Wts. Wts and its positive regulator Salvador originally were identified as tumor suppressor genes that function to coordinate cell proliferation and cell death. Loss-of-function mutants of either gene cause a progressive defect in the maintenance of the dendritic arbors, resulting in large gaps in the receptive fields (Fig. 20.3). Time-lapse studies suggest that the primary defect is in the maintenance of terminal dendrites, so Wts may normally function to stabilize these dendrites.

Figure 20.3 Dendritic fields are largely unchanged once established during development. Late-onset dendritic loss in Drosophila warts mutants (wts−/−) in late larval stages. Live images of wild-type (WT) and wts mutant (wts) dendrites of class IV da neurons at different times after egg laying (AEL). In wts mutants, dendrites initially tile the body wall normally but progressively lose branches at later larval stages.

Adapted from Emoto et al. (2006).

How are the establishment and maintenance of dendritic fields coordinated? In Drosophila class IV neurons, the Ste-20-related tumor suppressor kinase Hippo (Hpo) can directly phosphorylate and regulate both Trc, which functions in the establishment of dendritic tiling, and Wts, which functions in the maintenance of dendritic tiling (Emoto, Parrish, Jan, & Jan, 2006). Furthermore, hpo mutants have defects in both establishment and maintenance of dendritic fields. How Hpo regulates the transition from establishment to maintenance of dendritic fields remains to be determined.

What might be the downstream genes regulated by Wts? In the Drosophila retina, Wts regulates cell proliferation and apoptosis by phosphorylating the transcriptional coactivator Yorkie (Huang et al., 2005), but Yorkie does not appear to function in dendrite maintenance. Instead, the Polycomb genes are good candidates as targets for Wts/Sav for dendritic maintenance. The Polycomb genes regulate gene expression by repressing developmentally regulated genes. Polycomb genes can be separated into two multiprotein complexes: Polycomb repressor complex 1 (PRC 1) and PRC2. PRC2 is thought to mark the genes to be silenced by methylating histone H3, and PRC1 then comes in and blocks transcription. Mutants of several members of PRC1 and PRC2 have dendrite maintenance phenotypes very similar to that of Wts. Further, genetic and biochemical experiments suggest a functional link between Hpo/Wts signaling and the Polycomb genes, and that Polycomb genes regulate the dendritic field in part through Ultrabithorax (Ubx), one of the Hox genes in Drosophila (Parrish, Emoto, Jan, & Jan, 2007a).

Extracellular Regulation of Dendritic Development

Regulation of Dendritic Differentiation and Dendrite Orientation

The developing cerebral cortex in mammals has been a valuable system to identify molecular mechanisms of dendritic growth control. Most excitatory cortical neurons are generated from precursors in the germinal zones lining the ventricle (Fig. 20.4). Once the cells become postmitotic, they migrate from the ventricular zone to the cortical plate. Following migration, pyramidal neurons extend an axon toward the ventricle and an apical dendrite toward the pial surface. To test the role of the local cortical environment in regulating the differentiation and guidance of nascent axons and dendrites, Polleux and Ghosh developed an in vitro assay in which dissociated neurons from a donor cortex were plated onto cortical slices in organotypic cultures. Neurons plated on cortical slices behave like the endogenous pyramidal neurons and extend an axon toward the ventricular zone and an apical dendrite toward the pial surface. Both the oriented growth of the axon and the apical dendrite are regulated by the chemotropic signal Sema 3A, which is present at high levels near the pial surface, and acts as a chemorepellant for axons and a chemoattractant for dendrites (Polleux, Giger, Ginty, Kolodkin, & Ghosh, 1998; Polleux, Morrow, & Ghosh, 2000).

Figure 20.4 Upper Panel: Development of the dendritic morphology of cortical pyramidal neurons. Pyramidal neurons are generated from radial glial precursors in the dorsal telencephalon during embryonic development. Upon cell cycle exit from the ventricular zone (VZ), young post-mitotic neurons migrate along the radial glial scaffold and display a polarized morphology with a leading process directed toward the pial surface and sometimes a trailing process directed toward the ventricle. The leading process later becomes the apical dendrite. The trailing process of some neurons (but not all) develops into an axon that grows toward the intermediate zone (IZ; the future white matter) once cells reach the cortical plate (CP). Upon reaching the top of the cortical plate, postmitotic neurons detach from the radial glial processes and have to maintain their apical dendrite orientation toward the pial surface and axon outgrowth orientation toward the ventricle, which appears to be regulated by Sema3A, which acts as a chemoattractant for the apical dendrite and a chemorepellant for the axon. Adapted from Polleux and Ghosh (2008). Lower Panel: A model of how sequential action of extracellular factors might specify cortical neuron morphology. A newly postmitotic neuron arrives at the cortical plate, where it encounters a gradient of Sema3A (Polleux et al., 1998), which directs the growth of the axon towards the white matter. The same gradient of Sema3A attracts the apical dendrite of the neuron toward the pial surface (Polleux et al., 2000). Other factors, such as BDNF and Notch, control the subsequent growth and branching of dendrites.

Adapted from (Polleux & Ghosh, 2008).

The basis of the differential response of axons and dendrites to Sema3A appears to be asymmetric targeting of sGC to the emerging dendrite, which regulates cGMP levels (Polleux et al., 2000). Inhibition of cGMP-dependent kinase by pharmacological or genetic perturbation leads to ectopic dendritic orientation (Demyanenko et al., 2005; Polleux et al., 2000). Experiments carried out in Xenopus spinal neurons indicate that modulation of cGMP signaling by semaphorins can convert axons into dendrites, suggesting that local control of cGMP may be important in regulation of dendritic differentiation (Nishiyama et al., 2011). In addition to cGMP signaling, the nonreceptor tyrosine kinases Fyn and Cdk5 play important roles in mediating the effects of Sema3A on cortical dendrite orientation (Morita et al., 2006; Sasaki et al., 2002).

The concept of dendritic guidance turns out to be a general one: studies in Drosophila show that diffusible proteins (Netrin A and B) secreted by midline cells activate a cell-surface receptor (Frazzled) to pattern dendrites of motor neurons (Furrer, Kim, Wolf, & Chiba, 2003; Huber, Kolodkin, Ginty, & Cloutier, 2003; Yu & Bargmann, 2001).

Regulation of Dendritic Growth and Branching

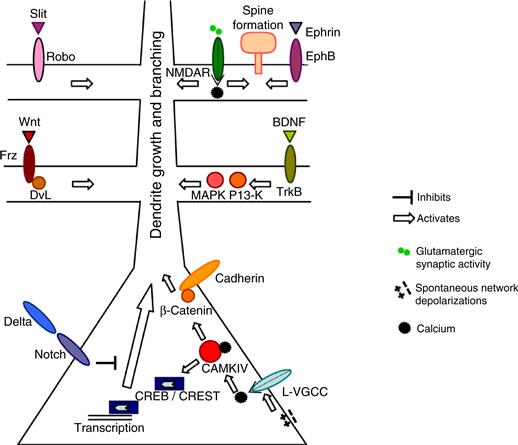

The growth and branching of dendrites can be influenced by a large number of extracellular signals (see Fig. 20.9). In this section we discuss how specific extracellular factors regulate the development of the dendritic tree.

Neurotrophins

Neurotrophins (NGF, BDNF, NT-3, and NT-4) exert their effects on the growth and branching of dendritic arbors through the Trk family of tyrosine kinase receptors. Experiments in which the effects of neurotrophins on dendritic growth control have been examined in slice cultures from mammalian hippocampus or cortex indicate that, in general, neurotrophins increase dendritic complexity of pyramidal neurons by increasing total dendritic length, the number of branchpoints, and/or the number of primary dendrites (Baker, Dijkhuizen, Van Pelt, & Verhaagen, 1998; McAllister, Lo, & Katz, 1995; Niblock, Brunso-Bechtold, & Riddle, 2000; Yacoubian & Lo, 2000). By contrast, BDNF injection into Xenopus optic tectum increases synapse density on tectal neurons without affecting dendritic arbor structure (Sanchez et al., 2006).

The complexity of neuronal dendrites is likely to be influenced by the action of multiple neurotrophic factors. For example, Osteogenic Protein-1 (OP-1), a member of the transforming growth-factor-beta (TGFβ) superfamily, increases dendritic growth and branching in dissociated embryonic cortical neurons (Le Roux, Behar, Higgins, & Charette, 1999). Insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) affects dendrite growth and branching of postnatal layer 2 cortical neurons (Niblock et al., 2000). Furthermore, insulin receptor signaling is required for visual experience–dependent enhanced dendritic arbor growth in Xenopus tectal neurons (Chiu, Chen, & Cline, 2008), illustrating that neurotrophin signaling mechanisms operate broadly across evolution.

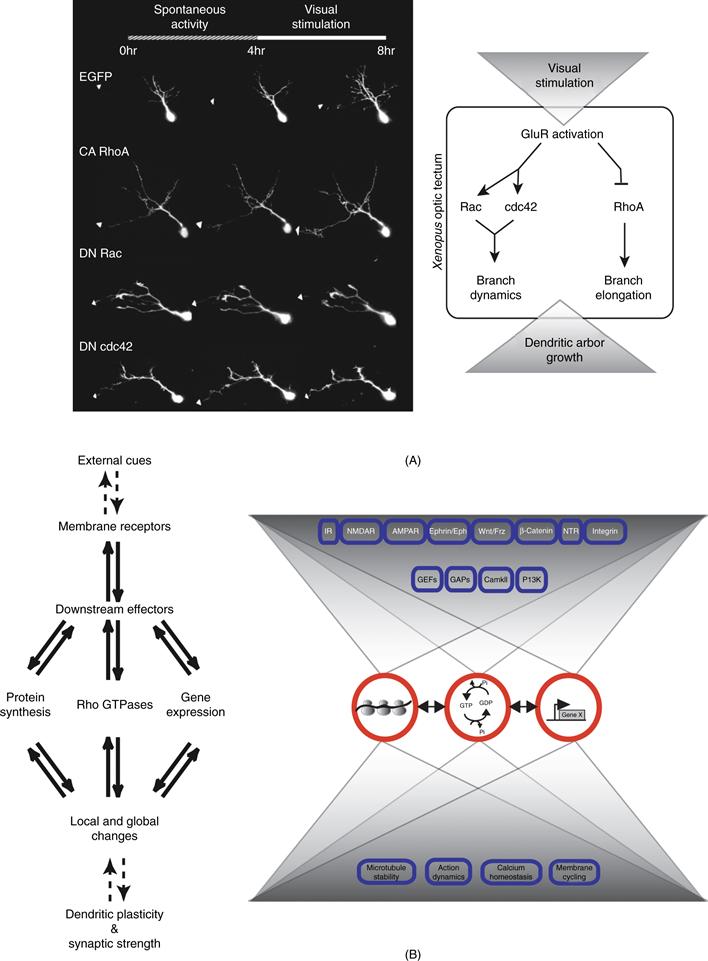

Recent work indicates that Trk receptors and most other tyrosine kinase receptors affect dendrite development through the MAP kinase and PI-3 kinase pathways, which in turn include PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome Ten), mTOR (mammalian Target of Rapamycin), and local protein synthesis (Chow et al., 2009; Jaworski, Spangler, Seeburg, Hoogenraad, & Sheng, 2005). In addition to control of local protein synthesis, these signaling pathways appear to influence neuronal morphology by regulating the activity of the Rho family GTPases, which mediate actin cytoskeleton dynamics and are known to induce rapid dendritic remodeling (Box 20.1; Fig. 20.5).

Box 20.1 Rho GTPases Control the Structure of the Dendritic Cytoskeleton

All the pathways that regulate dendritic development necessarily converge on the regulation of the cytoskeleton, which is controlled by the Rho GTPases. It is noteworthy that many, if not all, of these pathways also affect gene expression and different aspects of dendritic function, such as synaptic transmission, calcium signaling, and neuronal excitability. Such divergence of signaling from extracellular cues assures that the development of dendritic structure and function are tightly coregulated.

The dendritic cytoskeleton is composed of bundles of microtubules extending within the center of the dendritic shaft, a cortex of actin sandwiched between the microtubular bundles and the plasma membrane, and an actin matrix at the tip of dendritic processes. Fine terminal dendritic branches, or filopodia, have actin filaments as their sole cytoskeletal component (reviewed in Van Aelst and Cline (2004)). Considerable effort has been devoted to understanding the interaction between extracellular signaling events and the cytoskeleton, since these interactions are likely to be essential for the highly stereotyped and yet plastic elaboration of the dendritic arbor structure. A general scenario is emerging in which an extracellular signal interacts with a cell surface receptor that activates a cascade controlling the RhoA GTPases that, in turn, affect both the actin- and microtubule-based cytoskeleton in dendrites (Newey et al., 2005). The significance of these Rho GTPase regulatory molecules for dendritic morphogenesis is perhaps best illustrated by the fact that the abnormal development of dendritic trees, a hallmark of several different types of mental retardation, is at least in part caused by deficient signaling via Rho GTPases (Govek, Newey, & Van Aelst, 2005).

The Rho GTPases regulate the cytoskeleton in all cell types, but the elaborate and plastic structure of neurons poses particularly fascinating regulatory constraints on GTPase signaling (da Silva & Dotti, 2002; Luo, 2000; Van Aelst & Cline, 2004). The Rho GTPases function as bimodal switches, cycling between inactive, GDP-bound and active, GTP-bound conformations. RhoA, Rac1, and cdc42 are arguably the best studied of the small Rho GTPases. These molecules regulate both actin and microtubule dynamics (Gundersen, Gomes, & Wen, 2004; Zheng, 2004), and the manipulation of their individual activities has shown that each plays a particular role in dendritic structure development (reviewed in Newey et al. (2005)). The interplay of these effects on the cytoskeleton is key in shaping the intricacy of dendritic trees.

As more refined methods are used to probe the molecular and cellular basis of structural plasticity, our understanding of the intricate web of control becomes more complete. A striking example is that of the in vivo dendritic arbor development of optic tectal neurons in Xenopus. These neurons respond to stimulation of the tadpole visual system with an increased dendritic arbor growth rate, which requires glutamate receptor activity (Sin et al., 2002). Expression of dominant negative or constitutively active forms of RhoA, Rac, and Cdc42 demonstrated the participation of the Rho GTPases in the activity-dependent enhanced dendritic arbor growth rate. Expression of dominant negative forms of Rac or Cdc42, or expression of active RhoA blocked dendritic arbor elaboration in response to visual stimulation (Li, Aizenman, & Cline, 2002; Li, Van Aelst, & Cline, 2000; Sin et al., 2002) (Fig. 20.5A). These data suggest that glutamatergic synaptic input regulates the development of dendritic arbor structure by controlling cytoskeletal dynamics and that the Rho GTPases are an interface between glutamate receptor activity and the cytoskeleton. Furthermore, these data and reports from other systems support a model in which Rac and Cdc42 activity regulate rates of terminal branch dynamics, whereas RhoA regulates extension of branches in response to activity (Ahnert-Hilger et al., 2004; Hayashi, Ohshima, & Mikoshiba, 2002; Lee, Winter, Marticke, Lee, & Luo, 2000; Li et al., 2000, 2002; Nakayama, Harms, & Luo, 2000; Ng et al., 2002; Pilpel & Segal, 2004; Ruchhoeft, Ohnuma, McNeill, Holt, & Harris, 1999; Scott, Reuter, & Luo, 2003; Sin et al., 2002; Wong, Faulkner-Jones, Sanes, & Wong, 2000).

Branch formation requires the regulation of local cortical actin dynamics to create protrusive forces that allow filopodial sprouting (Luo, 2000). Time-lapse imaging indicates that filopodia are extremely dynamic, consistent with the rapid assembly and disassembly of actin filaments (Hossain, Hewapathirane, & Haas, 2011). The stabilization of filopodia and their extension as branches likely depend on their invasion by microtubules. Although the invasion of filopodia by microtubules is a key regulatory event in dendritic arbor development, the mechanisms regulating this process are unknown. Microtubules generate the mechanical forces necessary for branch elongation and can serve as tracks for the delivery of new membrane as branches extend (Horton & Ehlers, 2003, 2004), as well as transport of ribonucleoprotein (RNP) granules that regulate local protein synthesis (Bagni & Greenough, 2005). A close interplay between actin and microtubules is fundamental for the cellular events leading to changes in dendritic architecture. Importantly, in nonneuronal cells, the activity of Rho GTPases not only induces changes in both actin and microtubules but is also itself modified by alterations in the dynamics of the two cytoskeletons, thus serving as the regulator for the interplay between actin and microtubules (Etienne-Manneville, 2004; Fukata, Nakagawa, & Kaibuchi, 2003; Wittmann & Waterman-Storer, 2001; Zheng, 2004).

The role of RhoA in regulating the extension of branches in response to activity relies on its capacity to control microtubule stabilization (e.g., via mDia; Palazzo, Cook, Alberts, & Gundersen, 2001) and favor polymerization of cortical actin (Da Silva et al., 2003; Nobes & Hall, 1995), whereas Rac and cdc42 act on branch dynamics by regulating actin (e.g., supporting filopodial formation; Luo, 2002) and by favoring microtubular dynamics (e.g., by regulating catastrophe rates; Daub, Gevaert, Vandekerckhove, Sobel, & Hall, 2001; Kuntziger, Gavet, Manceau, Sobel, & Bornens, 2001). The description of the function of other Rho GTPases, such as that of Rnd2 in regulating branching via its effector Rapostlin (Negishi & Katoh, 2005), will help in the detailed understanding of how Rho GTPases regulate dendritic arbor development.

Rho GTPases are distributed ubiquitously throughout the neuronal cytoplasm (Govek et al., 2005), and, consequently, the activity of these proteins must be restrained in dendrites by resident upstream regulators. The link between incoming signals, for instance by activation of neurotransmitter receptors, and GTPase activity is mediated by GTPase regulatory proteins, which are particularly interesting because they are capable of integrating extracellular signaling with other signaling events relevant to neuronal structure. These include the guanine exchange factors (GEFs), which activate GTPases by favoring the substitution of GDP for GTP, and GTPase activating proteins (GAPs), which inactivate GTPases by inducing GTP hydrolysis (Bernards & Settleman, 2004; Schmidt & Hall, 2002). A rush of recent papers has examined the potential participation of several GEFs and GAPs in activity-dependent dendritic structural plasticity. GAPs can regulate dendritic development, as is exemplified by the observation that p190 RhoGAP is necessary for the dendritic remodeling that allows the shift from pyramidal to nonpyramidal morphologies in cortical cultures (Threadgill, Bobb, & Ghosh, 1997). Importantly, p190 RhoGAP is likely to exert its effect in an activity-dependent manner as indicated by its importance in fear memory formation in the lateral amygdala (Lamprecht, Farb, & LeDoux, 2002).

GEFs also play important roles in regulating dendrite arbor structure. For instance, Tiam1, a Rac-GEF, is located in dendrites and in particular in spines in cortical and hippocampal neurons. Tiam is noteworthy because it associates with the NMDA receptor, is phosphorylated in a calcium- and NMDA receptor–dependent manner, and is required for dendritic arbor development (Tolias et al., 2005). This is particularly interesting if one considers that the closely related member of the Dbl family of GEFs (Rossman & Sondek, 2005), Trio, regulates the development of axons in a potentially calcium-dependent manner (Debant et al., 1996), indicating the subcellular localization within different neuronal compartments is key to the specificity of GEF function. Kalirin, another example of a RhoGEF, in this case a dual RhoA- and Rac1-GEF, has been shown to regulate the development and maintenance of dendritic arbors by modulation of RhoA and Rac activities (Penzes et al., 2001). Recruitment of this Rho GTPase regulator in dendrites depends on the ephrin-EphB transynaptic signaling pathway, another cell surface signaling system linked to the actin cytoskeleton regulatory machinery. EphrinB-EphB receptor signaling may coordinate pre- and postsynaptic structural and functional development (Palmer & Klein, 2003). Its activation results in the translocation of Kalirin to synaptic sites and the activation of a signaling pathway involving Rac1 and the specific downstream effector PAK (Penzes et al., 2003). One intriguing possibility is that the Ephrin-EphR signaling could be coordinated with regulation of NMDA receptor distribution and calcium-permeability in postsynaptic sites (Dalva et al., 2000; Takasu, Dalva, Zigmond, & Greenberg, 2002). This kind of crosstalk between proteins involved in cell–cell contact and neurotransmitter receptors provides evidence for coregulation of development of dendritic arbor structure and synaptic communication.

Figure 20.5 Visual experience regulates dendritic growth through Rho, Rac, and Cdc42. (A) Visual stimulation over a 4-hour period increases the rate of dendrite growth in optic tectal neurons from Xenopus, Expression of constitutively active (CA) RhoA, dominant negative (DN) Rac, or DN Cdc42 affect specific aspects of dynamic dendritic arbor growth, as shown in the images of GFP-expressing tectal neurons collected in vivo. As summarized in the diagram on the right, visual stimulation, acting through glutamate receptors, triggers enhanced dendrite growth by regulating the Rho GTPases. (B) External cues acting through membrane receptors and downstream signaling pathways regulate functional and structural dendritic plasticity. Multiple mechanisms operate in parallel to accomplish and control neuronal plasticity.

From Bestman et al. (2008).

Slit/Robo Signaling

The Slits are a well-studied family of multifunctional guidance cues that have been shown to both repel axons and migrating cells, as well as promote elongation and branching of developing sensory axons (reviewed in Huber et al., 2003). Generally, Slits exert their effects through binding to specific members of the Roundabout, or Robo, family of receptors. Slit1, and two of the three Robo receptors, Robo1 and Robo2, are expressed in the developing cortex during the time of initial axon and dendrite differentiation. Slit proteins simultaneously repel pyramidal neuron axons and stimulate dendrite growth and branching and these effects of Slit1 are mediated by the Robo1 and 2 receptors (Whitford et al., 2002). Thus, in contrast to the guidance role that Sema3A plays in orienting apical dendrites, Slit1 acts as a more general dendrite growth and branching signal for cortical neurons.

WNT Signaling

Another illustration of the ability of individual signals to control diverse biological responses including the control of axonal and dendritic development is provided by the WNT family of secreted proteins. The WNTs are a large family of proteins initially identified as potent morphogens involved in patterning organ development in both invertebrates and vertebrates. WNTs also have been shown to regulate cell proliferation, migration, and survival (Ciani, Krylova, Smalley, Dale, & Salinas, 2004; Ciani & Salinas, 2005). WNT proteins can function as axon-guidance molecules and as target-derived signals that regulate axonal remodeling and synapse formation (Budnik & Salinas, 2011; Hall, Lucas, & Salinas, 2000; Krylova et al., 2002). WNT proteins signal through at least three different pathways. The binding of WNT proteins to Frizzled receptors results in the activation of the scaffold protein Dishevelled (Dvl). In the so-called canonical pathway, WNT proteins signal through Dvl to inhibit GSK3-β a serine/threonine kinase. Inhibition of GSK3-β, in turn, activates β-catenin-mediated gene transcription. WNT proteins can also signal through Dvl to regulate Rho GTPases. Finally, WNT proteins can activate a Ca2-dependent pathway, again through Dvl. WNT proteins induce axonal remodeling through the activation of Dvl and the subsequent inhibition of GSK3-β (Hall et al., 2000). Dvl has been shown to act locally to regulate microtubule stability by inhibiting a pool of GSK3-β through a β-catenin- and transcriptional-independent pathway (Ciani et al., 2004).

WNT proteins control dendritic arborization of hippocampal neurons (Rosso, Sussman, Wynshaw-Boris, & Salinas, 2005). Salinas and colleagues have found that Wnt7b is expressed in the mouse hippocampus and induces dendritic arborization of hippocampal neurons during development. This effect is mimicked by the expression of DVL. Importantly, analyses of the Dvl1 mutant mouse revealed that DVL1 is crucial for dendrite development, as hippocampal neurons developed shorter and less complex dendrites in the mutant than in the wild-type. A dominant-negative β-catenin does not block DVL function in dendrites, suggesting that the WNT canonical pathway is not involved. In this case WNT7B and DVL signal through a noncanonical pathway in which the small GTPase Rac, but not Rho, is involved. First, endogenous DVL associates with Rac but not Rho in hippocampal neurons. Second, WNT7B or expression of DVL activates Rac in hippocampal neurons. Last, expression of a dominant- negative Rac blocks DVL function in dendrites.

Inhibition of the WNT pathway by SFRP1 (a secreted antagonist of WNT proteins) decreases Rac activation by WNT7B and blocks the effect of WNT7B in dendrite development (Rosso et al., 2005). Rosso et al. also report that WNT7B and DVL activate JNK, a downstream effector of Rac. Inhibition of JNK blocks DVL function in dendrites, whereas pharmacological activation of JNK enhances dendrite development. It remains to be determined whether JNK acts downstream of Rac, or whether the WNT–DVL pathway regulates Rac and JNK independently. Although Rho GTPases are well-known modulators of dendrite development and maintenance (see Box 20.1), the mechanisms by which extracellular factors modulate these molecules during dendrite morphogenesis remains poorly understood. The findings reported by Rosso et al. (2005) demonstrate that DVL functions as a link between WNT factors and Rho GTPases in dendrites, and they reveal a novel role for JNK in dendrite development.

Cadherins and Catenins

One of the central challenges in the study of dendritic development is to understand how extracellular cues that regulate dendritic branching are integrated with Ca2 activity-dependent signals. A potential clue comes from recent results exploring the role of β-catenin and cadherins in dendritic branching (Yu & Malenka, 2003). Overexpression of β-catenin (and other members of the cadherin/catenin complex) enhances dendritic arborization, whereas sequestering endogenous β-catenin causes a decrease in dendritic branching. Importantly, the authors show that blocking β-catenin prevents the enhancement of dendritic morphogenesis caused by neuronal depolarization. Furthermore, the release of secreted WNT, which occurs during normal neuronal development, is enhanced by manipulations that mimic increased activity, and WNTs contribute to the effects of neural activity on dendritic arborization. These results indicate that β-catenin is an important mediator of dendritic morphogenesis and that WNT β-catenin signaling is likely to be important during critical stages of dendritic development (Yu & Malenka, 2003).

These observations are reinforced by the recent demonstration that another class of cadherins (Celsr1–3) regulates dendritic branching of cortical pyramidal neurons (Shima, Kengaku, Hirano, Takeichi, & Uemura, 2004). This class of cadherins has been identified in vertebrates as orthologs of flamingo, a gene previously implicated in the control of dendritic development in Drosophila (Gao, Kohwi, Brenman, Jan, & Jan, 2000). Shima et al. (2004) combined loss-of-function techniques including RNAi-mediated gene silencing in single neurons using biolistic-delivery in P8 organotypic slice cultures to demonstrate that knocking-down Celsr2 expression in both layer 5 pyramidal neurons and Purkinje cerebellar neurons significantly reduces dendritic branching (Shima et al., 2004). Furthermore, using the same technique, Shima et al. performed a structure-function analysis demonstrating that these effects of Celsr2 on dendritic branching require the integrity of a site on the extracellular portion outside the cadherin-domain as well as a portion of the intracellular domain called the EGF-HRM region. These results indicate that cadherins play an important role in the control of dendritic complexity.

Dendritic Development and Circuit Formation in Mammalian Retina

Why are dendrites so elaborately patterned? A main reason is that their form underlies their function, and their function can be quite complex. The size, shape, branching pattern, and position of dendritic arbors are main determinants of what inputs they receive and how those inputs are integrated. These relationships have been demonstrated in many regions of the nervous system of both vertebrates and invertebrates. Here, to exemplify the relationship between dendritic development and circuit function, we focus on the vertebrate retina.

Retinal circuitry is described in Chapter 26, and summarized in Figure 26.2. Briefly, light excites photoreceptors, which form synapses on dendrites of bipolar cells; the axons of these cells form synapses on retinal ganglion cells (RGCs), whose axons send information to the brain. Horizontal cells and amacrine cells mediate lateral interactions. Complexity in this seemingly simple circuit arises from the existence of multiple subtypes of each main cell type—at least 12, 30, and 20 subtypes of bipolar, amacrine cells, and retinal ganglion cells, respectively, in mammals, along with several photoreceptor subtypes (red, blue, and green cones plus rods in humans) and 2–4 horizontal cell types in most species (but only one in mice). The synapses these cells make and receive are highly specific and the circuits they form are complex. As development proceeds, the dendrites of RGCs and amacrine cells and axons of bipolar cells extend to form the inner plexiform layer through a sequence of intercellular interactions (Godinho et al., 2005; Mumm et al., 2006). We will describe two main features of dendritic development, termed laminar and lateral specificity, that help explain how intrinsic and extrinsic factors regulate the development of retinal neuronal dendrites into circuits. We also mention studies from Drosophila da neurons, introduced above, in which similar phenomena have been studied in greater molecular depth.

Laminar Specificity in the Inner Plexiform Layer

The inner plexiform layer (IPL) is divided into a series of at least 10 narrow, parallel sublaminae, with arbors of individual RGCs confined to just one (monostratified) or two (bistratified) of the sublaminae. Distinct RGC subtypes display distinct sublaminar patterns. Likewise, axons of bipolar cells and processes of amacrine cells (amacrine cell processes both make and receive synapses but are generally called dendrites) are also confined to few sublaminae in subtype-specific patterns. Thus, the laminar restriction of dendrites and axons in the IPL is a main determinant of synaptic connectivity, and therefore the visual features to which subsets of RGC respond. For example, dendrites of RGCs that respond to decreases and increases in light intensity (so-called OFF and ON cells) are restricted to the outer and inner halves of the IPL, respectively, where they receive synapses from the specific subsets of interneurons that endow them with these response properties (Famiglietti & Kolb, 1976; Roska & Werblin, 2001).

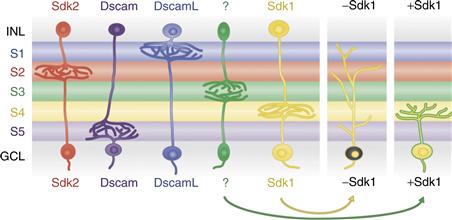

How does laminar specificity arise? Most IPL synapses form prior to visual experience, though they may be modified by electrical activity (see below). An appealingly simple idea is that expression of a homophilic adhesion molecule by pre- and postsynaptic partners, perhaps as a consequence of their cell autonomous differentiation programs, could match them to each other. In chick embryos, four closely related transmembrance recognition molecules of the immununoglobulin superfamily—Dscam, DscamL, Sidekick-1, and Sidekick-2—appear to play such roles. They are expressed by nonoverlapping subsets of bipolar, amacrine, and retinal ganglion cells that form synapses in distinct IPL sublaminae (Figure 20.6). Each of the four proteins is concentrated within the appropriate sublaminae and each mediates homophilic adhesion. Ectopic expression of any one of them in small groups of cells redirects their dendritic processes to the sublamina in which that immununoglobulin superfamily is most prominent. Conversely, when expression of any of the four is decreased, with interfering RNAs, the processes wander beyond their appropriate sublaminae (Yamagata & Sanes, 2008; 2010; Yamagata, Weiner, & Sanes, 2002). Together, these results suggest the existence of an “Ig superfamily code” for laminar specificity in retina. Genetic studies indicate that Dscams and Sidekicks also mediate laminar specificity in mouse retina (Fuerst, Harris, Johnson, & Burgess, 2010; Yamagata & Sanes, 2011), although the situation is complicated by the fact that Dscams (but not Sidekicks) also act as repellents implicated in dendritic patterning in the orthogonal plane (Fuerst, Koizumi, Masland, & Burgess, 2008; Fuerst et al., 2009; see below).

Figure 20.6 Expression of Sidekick 1, Sidekick 2, Dscam, and DscamL by nonoverlapping subsets of neurons in chick retina. Processes of most neurons that express each gene arborize in the same inner plexiform sublaminae, and altered expression of the gene (illustrated for Sidekick 1 in RGCs) leads to redistribution of their dendrites.

Recent studies have implicated the semaphorins in determining how particular connections come to occupy specific positions. The semaphorins are a diverse set of transmembrane and secreted ligands that signal through receptors of the plexin and neuropilin families. As noted above, the semaphorins had already been implicated in sculpting dendritic arbors of cortical neurons. Retinas from mice lacking various combinations of receptors and/or ligands have mistargetted arbors (Matsuoka et al., 2011a, 2011b). Clearly the codes have yet to be fully broken, but Dscams, Sidekicks, and Semaphorins account for only a fraction of the laminar choices that retinal axons make. However, an attractive model is that cues such as Semaphorins and Plexins help place arbors in appropriate laminar regions, where recognition molecules such as Sidekicks and Dscams further refine sublaminar patterns and promote specific connectivity among arbors that coexist within sublaminae.

Lateral Specificity in the Inner Plexiform Layer: Dendro–Dendritic Interactions Regulate the Shape and Organization of Dendritic Fields

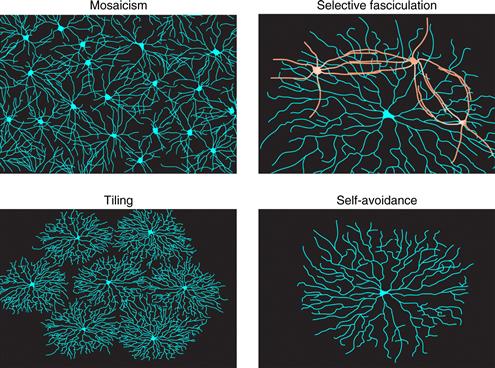

Dendrites are highly organized within the “x-y plane” of the retina. This type of organization is very important for the function of the retinal circuit. For example, the size and shape of an RGC’s arbor are prime determinants of its receptive field; the even spacing of neuronal dendrites and the degree of dendritic arbor overlap ensure uniform coverage of each part of the visual field by a full set of processing elements. Dendro–dendritic interactions have a profound influence on the size and shape of the dendritic field, as well as the spatial relationship between dendritic fields. In many areas of the nervous system, dendrites of different types of neurons are intermingled and packed into a tight space. This arrangement is not random but well organized. At least four mechanisms contribute to the orderly organization of dendritic fields: tiling, mosaicism, self-fasciculation, and self-avoidance (Fig. 20.7).

Figure 20.7 Four cellular processes that lead to regular arrangement of dendrites in the tangential plane of the retina’s inner plexiform layer.

Tiling

Tiling, first discovered in mammalian retina (Wassle, Peichl, & Boycott, 1981), refers to an arrangement in which arbors of individual neurons of a single subtype overlap minimally. A leading model is that dendrites of a given neuronal class grow until they are stopped by repulsive signals from the dendrites of their neighbors, leading to an arrangement in which arbors efficiently fill a field while avoiding overlap (Grueber & Sagasti, 2010). The degree of tiling is quantified by a “coverage factor,” which corresponds to the number of arbors of a given subtype a pin piercing the retina vertically would encounter. Thus, for perfect tiling, the coverage factor is 1.0. Dendrites of a few RGC subsets form tiled arrays in this sense (Dacey, 1993), as do the axonal arbors of many classes of bipolar cells (Wassle, Puller, Muller, & Haverkamp, 2009), but in fact dendrites of most RGC and amacrine subtypes do not tile: their coverage factors are significantly >1 and range up to >30 (Devries & Baylor, 1997; Peichl & Wassle, 1979). Thus, for these cells, regulation of dendritic size and control of dendritic overlap must arise from other mechanisms. One such mechanism is mosaicism (discussed below).

Tiling requires some cell surface recognition molecules to mediate the homotypic repulsion between neurons of the same type. Although the signal(s) that mediate vertebrate tiling behavior remain to be identified, studies in Drosophila and C. elegans have shown that the evolutionarily conserved protein kinase Tricornered (Trc) and the putative adaptor protein Furry (Fry), are important components of the intracellular signaling cascade involved in tiling (Emoto et al., 2004; Gallegos & Bargmann, 2004). In trc or fry mutants, dendrites no longer show their characteristic turning or retracting response when they encounter dendrites of the same type of neuron. In the mutants, unlike in the wild-type, there is extensive overlap of dendrites between adjacent neurons of the same kind. As a result, the mutant neurons have enlarged dendritic fields (Emoto et al., 2004).

Mosaicism

Neurons of most retinal subtypes are spaced more evenly than would be expected by chance alone. This regularity can be measured as the reduced probability of finding two cells of a single type near each other; the presence of an “exclusion zone” defines and characterizes the so-called “mosaic” arrangement (Eglen, 2006; Novelli, Resta, & Galli-Resta, 2005; Wassle & Riemann, 1978). Even in the absence of tiling, mosaics can help distribute each cell type evenly across the retina, thus optimizing dendritic coverage. Remarkably, mosaics are independent of each other; while a neuron of one subtype is unlikely to be adjacent to another of the same subtype, there is no restriction on its spatial relationship to neighboring neurons of other subtypes (Rockhill, Euler, & Masland, 2000), suggesting that molecular cues expressed by specific subtypes pattern mosaics by mediating homotypic (within-subtype) short-range repulsive interactions. Recently, a transmembrane protein called MEGF10 was found to mediate homotypic repulsive interactions critical for mosaic spacing of two interneuronal subtypes that occupy distinct cellular strata: horizontal cells and starburst amacrine cells (Kay & Sanes, 2011).

Selective Fasciculation

In some cases, dendrites of a particular neuronal subtype not only overlap, but they fasciculate. These associations presumably augment the specificity of the synapses that pass information laterally through the retina—for example, the electrical synapses that interconnect horizontal cells and the chemical synapses that interconnect starburst amacrine cells. Numerous cell adhesion molecules have been identified that promote fasciculation in other systems, and several are expressed by subsets of retinal neurons, but none has so far been shown to function in the IPL. On the other hand, the Dscams, mentioned above as mediators of laminar specificity, appear to have a separate role as modulaters of fasciculation in mouse retina. Intriguingly, their role is a negative one; in their absence, neurites hyperfasciculate, leading to loss of selectivity and formation of large bundles that disrupt tiling and mosaicism (Fuerst et al., 2008, 2009). Thus, the selectivity of lateral interactions appears to require a proper balance between attractive and repellent interactions.

Self-Avoidance

Self-avoidance is a phenomenon in which neurites of a cell can recognize and avoid other neurites emanating from the same cell, while interacting freely with neurites emanating from other, similar neurons (Grueber & Sagasti, 2010). Self-avoidance thus leads to maximal and uniform coverage of receptive or projective fields by an individual neuron, while allowing multiple neurons to share the same field. The remarkable feature of self-avoidance is that it requires endowing neurons with individual molecular identities so they can discriminate between self and nonself neurites within a subtype (Zipursky & Sanes, 2010). For example, strict self-avoidance among retinal starburst amacrine cell dendrites is what endows them with the radial shape for which they are named, yet the dendrites bundle with dendrites of other starbursts and even form numerous synapses with them (Lefebvre & Sanes, 2011). Some RGC subtypes also show dendritic self-avoidance (Montague & Friedlander, 1991).

In Drosophila, da neuronal dendrites show self-avoidance that is attributable to the expression of Dscam1, a member of the immunoglobulin superfamily, originally identified as an axon guidance receptor. Alternative splicing of DSCAM1 in flies can potentially generate over 38,000 isoforms (Schmucker et al., 2000). A neuron typically expresses only a couple dozen of those isoforms (Neves, Zucker, Daly, & Chess, 2004). Dscam appears to be involved in self-avoidance through isoform-specific homophilic binding (Hummel et al., 2003; Wang, Zugates, Liang, Lee, & Lee, 2002; Zhu et al., 2006) in which neurites expressing the same set of Dscam isoforms repel one another (Wojtowicz et al., 2004). Mutant da neurons devoid of Dscam exhibit dendrite bundling and a crossing-over phenotype. This self-avoidance phenotype can be rescued by expressing a randomly selected single DSCAM isoform in the neuron, suggesting that Dscam is necessary in the da neuron for their dendritic self-avoidance, but the particular isoform is not important (Hughes et al., 2007; Matthews et al., 2007; Soba et al., 2007). In mice, Dscams may also play a role in self-avoidance, but they do not have numerous isoforms, so their roles are generic; they limit interactions of neurites both within an arbor and between arbors (isoneuronally and heteroneuronally). On the other hand, a gene cluster encoding a set of >50 protocadherins does exhibit isoform diversity, homophilic specificity, and combinatorial expression, suggesting that they could act in vertebrates as Dscam1 does in flies (Zipursky & Sanes, 2010). Indeed, deletion of the 22 genes of the protocadherin gamma subcluster markedly degrades self-avoidance among dendrites of mouse starburst amacrines (Lefebvre & Sanes, 2011).

Activity-Dependent Dendritic Development

Synaptic inputs play a significant role in controlling dendritic arbor development. Synaptic communication allows pre- and postsynaptic neurons to assess potential partners within a developing circuit, to establish and strengthen optimal connections, and to prune back or eliminate suboptimal contacts. Experience-dependent effects on brain development are readily demonstrated in sensory projections where afferent input can be manipulated from the periphery. In vivo imaging experiments in the visual system of Xenopus tadpoles showed that a relatively brief 4 hour period of simulated motion stimulus results in significant increased dendritic arbor growth rate, that requires glutamatergic synaptic transmission and Rho GTPase activity (Sin et al., 2002) (Fig. 20.5). Electrophysiological recordings from tectal neurons in animals with short-term visual enhancement (STVE) indicate that the visual experience increases synaptogenesis and synapse maturation (Aizenman & Cline, 2007), promotes maturation of tectal circuitry (Pratt, Dong, & Aizenman, 2008), and increases signal to noise in visual stimulus detection (Aizenman, Akerman, Jensen, & Cline, 2003). Recently experience-dependent increases in gene transcription were shown to regulate dendritic development and visual system function (Schwartz, Schohl, & Ruthazer, 2009, 2011). Together these studies indicate that sensory inputs activate a divergent range of cellular events that cooperate to orchestrate the development of functional circuits.

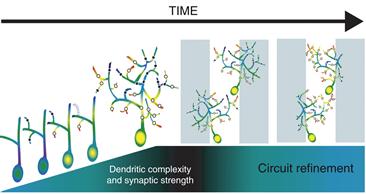

The Synaptotrophic Model Of Dendrite Development

How does activity regulate dendrite development? We will address this complex question by starting at the proximal site of activity-dependent regulation: the synapse. Considerable evidence supports the Synaptotrophic model of arbor development, presented by Vaughn (Cline & Haas, 2008; Vaughn, 1989; Vaughn, Barber, & Sims, 1988), which postulates that the formation and stabilization of synaptic contacts control the elaboration of dendritic (and axonal) arbors by regulating the stabilization or retraction of dynamic branches in the arbor (Fig. 20.8). Although the greatest numerical increase in synapse density in mammalian cortex occurs after lamination has occurred and many pyramidal cells have extended dendrites (Rakic, Bourgeois, Eckenhoff, Zecevic, & Goldman-Rakic, 1986), a key observation from Vaughn’s EM studies was that synapses form on arbors as the arbors elaborate (Vaughn, 1989; Vaughn et al., 1988). Indeed, whole cell recordings from newly differentiated optic tectal neurons in Xenopus or cortical neurons in turtle demonstrate that they have glutamatergic and GABA ergic synaptic inputs as soon as they extend their first dendrites (Blanton & Kriegstein, 1991; Wu, Malinow, & Cline, 1996).

Figure 20.8 Schematic diagram of the effect of synaptic input on dendrite development. During dendritic development, newly generated glutamatergic synapses are mediated primarily by NMDA type glutamate receptors (black dots). With the addition of AMPA type glutamate receptors (white dots), synapses can be active at resting membrane conditions and overall synaptic strength is increased leading to dendritic branch stabilization. Dendrites with relatively weak synapses lacking AMPA receptors are retracted (dotted line). The resulting local increases in calcium influx through AMPA/NMDA containing synapses (indicated with “hot” colors) may enhance rates of branch addition and further stabilization. Newly stabilized branches become the substrate for further branch additions. It is the interplay between the dendrites and their synaptic partners that leads to selective stabilization and elaboration of branches toward appropriate target areas (gray and white bars) that is essential for circuit refinement. These processes are not just important during development, but underlie changes in circuit refinement in the mature nervous system.

From Bestman et al. (2008).

Glutamatergic synapse formation is a multistep process in which an initial adhesion event is rapidly followed by synaptic transmission mediated by NMDA receptors. NMDA receptor activity promotes the trafficking of AMPA receptors into nascent synapses, which renders the synapses functional of resting potential (Cline, Wu, & Malinow, 1997). The Synaptotrophic hypothesis predicts that manipulations of synapse formation or synapse stabilization would affect dendritic arbor development. Adhesive events mediated by neurexin-neuroligin were recently shown to be required for tectal cell dendritic development (Chen, Tari, She, & Haas, 2010), consistent with Vaughn’s idea. Time-lapse in vivo imaging experiments showed that blockade of NMDA or AMPA receptors or interference with their trafficking perturbs tectal cell dendritic arbor development by interfering with addition or stabilization of dendritic branches (Haas, Li, & Cline, 2006; Rajan & Cline, 1998). Genetically decreasing NMDA receptor subunit expression also disrupted dendritic arbor development in the rodent somatosensory system (Lee, Lo, & Erzurumlu, 2005). Time-lapse imaging demonstrated that blocking trafficking of AMPA receptors into developing synapses increased the rates of branch retractions in the developing dendritic arbor and increased the proportion of transient dendritic branches (Cline & Haas, 2008; Haas et al., 2006), exactly as predicted by the Synaptotrophic hypothesis, that strengthening synapses formed onto newly established dendritic branches would stabilize the branches. Similarly in the hippocampus and cortex, perturbing AMPA receptor activation or trafficking affects synapse maturation and dendrite arborization on pyramidal neurons (De Marco Garcia, Karayannis, & Fishell, 2011; Shi, Cheng, Jan, & Jan, 2004a; Shi, Cox, Wang, Jan, & Jan, 2004b), again supporting the general principle that afferent inputs control dendritic arbor development in vivo.

During early stages of neuronal development, GABAergic synaptic activity depolarizes neurons from their resting potential because the reversal potential for chloride is relatively positive due to the delayed expression of the KCC2 chloride transporter. In Xenopus neurons, premature expression of KCC2 blocked the maturation of glutamatergic synaptic inputs and indicated that depolarizing GABAergic inputs cooperate with NMDA receptors to promote AMPA receptor trafficking into developing synapses (Akerman & Cline, 2006). Premature expression of KCC2 in cortical neurons impaired dendritic arbor development (Cancedda, Fiumelli, Chen, & Poo, 2007), suggesting that depolarizing GABAergic input might affect dendritic arbor development indirectly through an effect on development of excitatory synaptic inputs. It is interesting to note that once dendritic arbors are elaborated, glutamatergic synaptic input activity and CaMKII stabilize dendritic arbor structure (Wu & Cline, 1998), suggesting that signaling cascades downstream of these events proximal to the synapse change as the neuron and circuit develop.

Recent studies provided the first evidence that inhibitory GABAergic inputs regulate dendritic arbor development. Shen, Da Silva, He, and Cline (2009) expressed a peptide in optic tectal neurons, called ICL, which interfered with the residence of GABAA receptors at synaptic sites. ICL expression selectively decreased inhibitory GABAergic, but not glutamatergic, synaptic inputs onto tectal neurons, shown by electrophysiological criteria. In vivo imaging experiments showed that ICL expression severely disrupted dendritic arbor development and experience-dependent structural plasticity, in striking similarity to the effect of interfering with glutamatergic synaptic maturation (Haas et al., 2006). Further studies showed that ICL-expression in tectal neurons significantly disrupted visual information processing and visually guided behavior (Shen, McKeown, Demas, & Cline, 2011). These studies demonstrate that both excitatory and inhibitory synaptic inputs regulate dendritic arbor development, but whether similar or unique mechanisms operate under these circumstances is not yet known.

Branch Retraction and Synapse Elimination

Although dendrite arbor elaboration clearly requires net branch addition and extension, both branch and synapse elimination are integral parts of dendritic arbor development. The final structure of cortical pyramidal dendrites is heavily influenced by pruning major portions of the arbor. For instance, a recent study in ferret visual cortex showed that layer 4 neurons initially form an apical dendrite, which is subsequently retracted to produce the classical stellate morphology. Furthermore, visual input is required for the pruning of the apical process (Callaway & Borrell, 2011). Another clear example of this phenomenon comes from study of the retina, where developing retinal ganglion cells transiently respond to both light on and light off events and their dendritic arbors terminate in both On and Off neuropil laminae. With normal visual experience, the bistratified dendritic arbors are pruned to On and Off laminae. Dark-rearing blocks the normal pruning of dendritic branches in retinal ganglion cells so that retinal ganglion cells remain responsive to On and Off visual stimuli (Tian & Copenhagen, 2003). In contrast to the relatively large-scale dendrite pruning mentioned above, a recent study, which combined in time-lapse imaging and subsequent serial section electron microscopic reconstruction of the imaged neuron, showed that synapse elimination is a prominent activity-dependent component of microcircuit assembly (Li, Erisir, & Cline, 2011). In this study, time-lapse in vivo imaging over periods of hours or days allowed identification of newly added or relatively stable dendritic branches, while the serial section EM allowed ultrastructural comparison of synaptic contacts on identified dynamic and stable branches. Although one might anticipate that new dendritic branches might have few synapses and that synapse density might increase with branch stabilization, this study showed otherwise. Surprising, newly emerged dendritic branches had a significantly higher synapse density compared to more stable branches. As dendritic branches stabilize, most synapses are eliminated and one input remains and becomes morphologically mature (Li & Cline, 2010). Furthermore, visual experience and NMDA receptor activity were required for both synapse elimination and synapse maturation. These data provide quantitative ultrastructural understanding of the activity-regulated cellular mechanisms contributing to dendritic arbor development.

Calcium-Dependent Mechanisms That Mediate Dendritic Growth

The effects of neuronal activity on dendritic arbor development are mediated by calcium signaling. Calcium levels in neurons are regulated by influx through voltage-sensitive calcium channels (VSCC), NMDA receptors, and calcium-permeable AMPA receptors, as well as by release of calcium from intracellular stores (Fig. 20.9). Release from internal stores principally involves calcium-induced calcium release (CICR) or activation by ligands that lead to the production of IP3, which acts on internal stores. Two major signaling targets of elevated intracellular calcium are calcium/calmodulin dependent protein kinases (CaMKs) and mitogen-activated kinase (MAPK), which have multiple effects on dendrite development that reflect rapid and local consequences of kinase activity, as well as regulation of gene transcription through calcium-responsive transcription factors, such as CREB and CREST.

Figure 20.9 A summary of signaling pathways by which neuronal activity influences dendritic development. The effects of neuronal activity on dendritic development are mediated by calcium influx via voltage-gated calcium channels (VGCCs) and NMDA receptors, as well as release from internal stores. Local calcium signals act via Rho family proteins to regulate dendritic branch dynamics and stability, whereas global calcium signals recruit transcriptional mechanisms to regulate dendritic growth.

Of the CaMKs, CaMKII has been most extensively studied in relation to a role in dendritic development and function because both CaMKII isoforms, αCaMKII and βCaMKII, are present at high levels in dendrites. Most functional heteromers of CAMKII in cells include both α and β isoforms, and the α to β ratio in the heteromer regulates its association with the actin cytoskeleton and therefore its microdistribution in cells (Lisman, Schulman, & Cline, 2002). CaMKII strengthens synapses and stabilizes or restricts dendritic growth of frog tectal neurons in vivo and mammalian cortical neurons in vitro (Redmond, Oh, Hicks, Weinmaster, & Ghosh, 2000; Wu & Cline, 1998). CaMKIV is predominately localized in the nucleus, where it can respond to cytosolic calcium transients that enter the nucleus and regulate dendritic morphology through transcription events (Mauceri, Freitag, Oliveira, Bengtson, & Bading, 2011). The best-characterized target of CaMKIV is the transcription factor CREB. A noteworthy effector of CREB is CPG15, candidate plasticity gene 15 (Nedivi, 1999; Nedivi, Fieldust, Theill, & Hevron, 1996; Nedivi, Hevroni, Naot, Israeli, & Citri, 1993). CPG15 is a highly conserved neurotrophic molecule, which can promote neural survival and differentiation in mammalian systems (Putz, Harwell, & Nedivi, 2005). CPG15 enhances dendritic and axon arbor elaboration, and increases synaptogenesis and synaptic strength when expressed in Xenopus optic tectal cells in vivo (Cantallops, Haas, & Cline, 2000; Nedivi et al., 1998). Furthermore, the trafficking of GPI-linked CPG15 to the surface of axons is activity-regulated (Cantallops & Cline, 2008), suggesting that sensory activity regulates both the transcription and cellular localization of CPG15, which in turn promotes and coordinates multiple aspects of circuit development.

Protein Synthesis Dependent Regulation of Dendrite Development

Protein synthesis can be regulated locally within dendrites by mRNA binding proteins, such as the fragile X mental retardation protein, FMRP, cytoplasmic polyadenylation element binding protein (CPEB), staufen, and pumilio. In general, these proteins bind specific mRNA cargo and hold them translationally silent until they are signaled to release the cargo for translational processing. The possibility that local protein synthesis in dendrites might affect neuronal morphology was first suggested from studies on material from patients with Fragile X Syndrome (Purpura, 1974), in which the spines on pyramidal cell dendrites were unusually long and thin. Work in a variety of systems has begun to elucidate the role of mRNA binding proteins in dendrite development. For instance, in Xenopus, in vivo imaging of neurons expressing dominant negative forms of CPEB showed that CPEB RNA binding and microtubule-based transport into dendrites was required for normal dendritic arbor development and visual experience–dependent structural plasticity. Furthermore, electrophysiological recordings show that cells that are deficient in CPEB function fail to integrate into the retinotectal circuit and do not respond to visual inputs (Bestman & Cline, 2008). Work in rodent visual cortex indicated that CaMKII translation was regulated by CPEB1 downstream of visual experience and NMDA receptor activity (Wells et al., 2001). Many candidate mRNA cargoes of CPEB have been identified bioinformatically. Given that CaMKII, which is just one protein that is translationally regulated by CPEB, is itself pleiotropic with respect to control of dendrite arbor development, it is clear that we must embrace the complexity of activity-dependent regulatory mechanisms controlling dendritic arbor development and circuit connectivity.

Convergence And Divergence

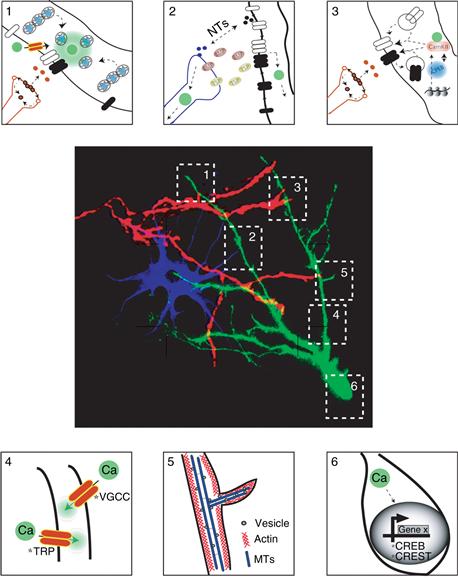

A wide variety of signaling pathways participate in dendritic arbor development by regulating different downstream events such as cytoskeletal rearrangements, Ca homeostasis, and membrane cycling (Fig. 20.10). In addition, many signaling cascades diverge, for example to regulate somatic gene expression, local protein synthesis as well as the Rho GTPases. These diverging pathways ultimately result in modifications of dendritic plasticity. One example of divergence comes from the activation of the Ras superfamily GTPases that regulate membrane cycling downstream of neurotransmitter receptor activity. Synaptic NMDA receptors activate the Rab GTPase Rab5 (Pfeffer & Aivazian, 2004) that in turn regulates the internalization and dephosphorylation of AMPA receptors (Brown, Tran, Backos, & Esteban, 2005), an event associated with changes in dendritic structure (Ikegaya et al., 2001) and synaptic strength. Similarly, decreasing or increasing the activity of the Ras GTPase Rap1 decreases or increases, respectively, dendritic arbor elaboration in vitro (Chen, Wang, & Ghosh, 2005). One way Rap1 works is by regulating how calcium influx affects CREB-dependent transcription (Chen et al., 2005). Rap1 also mediates the internalization of AMPA type glutamate receptors from local synaptic sites in response to NMDA receptor signaling (Zhu, Qin, Zhao, Van Aelst, & Malinow, 2002). Since blocking glutamate receptor activity also decreases dendritic arbor development (Rajan & Cline, 1998), it is possible that Rap1 may act principally to control cell surface levels of glutamate receptors and this, in turn, affects dendritic arbor elaboration, as shown by interfering with AMPA receptor trafficking (Haas et al., 2006; Shi et al., 2004b). As with the Rho GTPases, Rap1 and the other GTPases regulating membrane cycling are at nodal points in the cascades controlling cell surface distribution of membrane proteins. For instance, Rap1 is downstream of other receptors, such as the neurotrophin receptors, plus GTPase-dependent membrane cycling regulates the cell surface distribution of signaling molecules, other than glutamate receptors. As illustrated in Figure 20.10, the pathways regulating dendritic arbor development are nonlinear and neither their regulation nor their targets are independent. Consequently, it is essential to investigate the function of these complex molecules in their normal in vivo context in order to dissect their endogenous functions.

Figure 20.10 Summary of multiple mechanisms that influence dendritic growth and remodeling. Dendritic arbors develop within a complex environment in which they contact and receive signals from afferent axons, glial cells, and other dendrites. Several changes occur at sites of contact between axons and dendrites, marked by 1 and 3 in the image, including local changes in enzyme activity, such as CaM kinase and phosphatases, receptor trafficking, and local protein synthesis. Interactions between glia and neurons, marked by #2, include release of trophic substances that regulate synapse formation and maintenance. Process outgrowth, represented by #4 and #5, is mediated by cytoskeletal rearrangements. Finally activity-induced gene transcription, #6, can change the constellation of protein components in neurons in response to growth factors or synaptic inputs.

Conclusion

Studies such as those summarized here, aided by computational approaches to map biochemical events in space and time, will ultimately lead to a complete appreciation of the signaling pathways that regulate dendritic structural and functional plasticity. Elucidation of these pathways will reveal mechanisms by which activity can rapidly affect dendritic structure, and over more-prolonged time frames, exert profound changes in the so-called intrinsic states of the dendritic tree by modifying gene expression (Goldberg, 2004). Knowledge of these events, together with an understanding of the integrative capacity of dendrites, is essential to grasp the function of neuronal circuits and the brain.

References

1. Ahnert-Hilger G, Holtje M, Grosse G, et al. Differential effects of Rho GTPases on axonal and dendritic development in hippocampal neurones. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2004;90:9–18.

2. Aizenman CD, Akerman CJ, Jensen KR, Cline HT. Visually driven regulation of intrinsic neuronal excitability improves stimulus detection in vivo. Neuron. 2003;39:831–842.

3. Aizenman CD, Cline HT. Enhanced visual activity in vivo forms nascent synapses in the developing retinotectal projection. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2007;97:2949–2957.

4. Akerman CJ, Cline HT. Depolarizing GABAergic conductances regulate the balance of excitation to inhibition in the developing retinotectal circuit in vivo. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2006;26:5117–5130.

5. Bagni C, Greenough WT. From mRNP trafficking to spine dysmorphogenesis: The roots of fragile X syndrome. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2005;6:376–387.

6. Baker RE, Dijkhuizen PA, Van Pelt J, Verhaagen J. Growth of pyramidal, but not non-pyramidal, dendrites in long-term organotypic explants of neonatal rat neocortex chronically exposed to neurotrophin-3. The European Journal of Neuroscience. 1998;10:1037–1044.

7. Bernards A, Settleman J. GAP control: Regulating the regulators of small GTPases. Trends in Cell Biology. 2004;14:377–385.

8. Bestman JE, Cline HT. The RNA binding protein CPEB regulates dendrite morphogenesis and neuronal circuit assembly in vivo. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105:20494–20499.

9. Bestman J, Santos Da Silva J, Cline HT. Dendrite development. In: Stuart G, Spruston N, Hausser M, eds. Dendrites. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press; 2008.

10. Blanton MG, Kriegstein AR. Spontaneous action potential activity and synaptic currents in the embryonic turtle cerebral cortex. The Journal of Neuroscience 1991;3907–3923.

11. Brown TC, Tran IC, Backos DS, Esteban JA. NMDA receptor-dependent activation of the small GTPase Rab5 drives the removal of synaptic AMPA receptors during hippocampal LTD. Neuron. 2005;45:81–94.

12. Budnik V, Salinas PC. Wnt signaling during synaptic development and plasticity. Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 2011;21:151–159.

13. Callaway EM, Borrell V. Developmental sculpting of dendritic morphology of layer 4 neurons in visual cortex: Influence of retinal input. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2011;31:7456–7470.

14. Cancedda L, Fiumelli H, Chen K, Poo MM. Excitatory GABA action is essential for morphological maturation of cortical neurons in vivo. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2007;27:5224–5235.

15. Cantallops I, Cline HT. Rapid activity-dependent delivery of the neurotrophic protein CPG15 to the axon surface of neurons in intact Xenopus tadpoles. Developmental Neurobiology. 2008;68:744–759.

16. Cantallops I, Haas K, Cline HT. Postsynaptic CPG15 promotes synaptic maturation and presynaptic axon arbor elaboration in vivo. Nature Neuroscience. 2000;3:1004–1011.

17. Chen SX, Tari PK, She K, Haas K. Neurexin-neuroligin cell adhesion complexes contribute to synaptotropic dendritogenesis via growth stabilization mechanisms in vivo. Neuron. 2010;67:967–983.

18. Chen Y, Wang PY, Ghosh A. Regulation of cortical dendrite development by Rap1 signaling. Molecular and Cellular Neurosciences. 2005;28:215–228.

19. Chiu SL, Chen CM, Cline HT. Insulin receptor signaling regulates synapse number, dendritic plasticity, and circuit function in vivo. Neuron. 2008;58:708–719.

20. Chow DK, Groszer M, Pribadi M, et al. Laminar and compartmental regulation of dendritic growth in mature cortex. Nature Neuroscience. 2009;12:116–118.

21. Ciani L, Krylova O, Smalley MJ, Dale TC, Salinas PC. A divergent canonical WNT-signaling pathway regulates microtubule dynamics: Dishevelled signals locally to stabilize microtubules. The Journal of Cell Biology. 2004;164:243–253.

22. Ciani L, Salinas PC. WNTs in the vertebrate nervous system: From patterning to neuronal connectivity. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2005;6:351–362.

23. Cline HT. Dendritic arbor development and synaptogenesis. Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 2001;11:118–126.

24. Cline H, Haas K. The regulation of dendritic arbor development and plasticity by glutamatergic synaptic input: A review of the synaptotrophic hypothesis. Journal of Physiological. 2008;586:1509–1517.

25. Cline HT, Wu G-Y, Malinow R. In vivo development of neuronal structure and function. Cold Spring Harbor Symposia Quantitative Biology. 1997;LXI:95–104.

26. Da Silva JS, Dotti CG. Breaking the neuronal sphere: Regulation of the actin cytoskeleton in neuritogenesis. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2002;3:694–704.

27. Da Silva JS, Medina M, Zuliani C, Di Nardo A, Witke W, Dotti CG. RhoA/ROCK regulation of neuritogenesis via profilin IIa-mediated control of actin stability. The Journal of Cell Biology. 2003;162:1267–1279.

28. Dacey DM. The mosaic of midget ganglion cells in the human retina. The Journal of Neuroscience. 1993;13:5334–5355.

29. Dailey ME, Smith SJ. The dynamics of dendritic structure in developing hippocampal slices. The Journal of Neuroscience. 1996;16:2983–2994.

30. Dalva MB, Takasu MA, Lin MZ, et al. EphB receptors interact with NMDA receptors and regulate excitatory synapse formation. Cell. 2000;103:945–956.

31. Daub H, Gevaert K, Vandekerckhove J, Sobel A, Hall A. Rac/Cdc42 and p65PAK regulate the microtubule-destabilizing protein stathmin through phosphorylation at serine 16. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276:1677–1680.