Chapter 24

The Somatosensory System

The somatosensory system has many responsibilities. Beyond the obvious need to bring to consciousness the events that occur along the skin surface, this system provides an organism with knowledge of where it is in space, and it provides the motor system with feedback to control and coordinate action. Those are functions so diverse that minute variations on a common theme cannot accomplish them all. That is, the many demands on the somatosensory system cannot be met by subtle changes in gene expression or pattern of synapses or location of cell bodies. As a result, single neurons, large ensembles and groups of interconnected regions in the somatosensory system use different tactics and strategies to achieve the goals of perception, homeostasis and sensory guidance of movement.

Peripheral Mechanisms of Somatic Sensation

All Somatic Sensation Begins with Receptors and Ganglion Cells

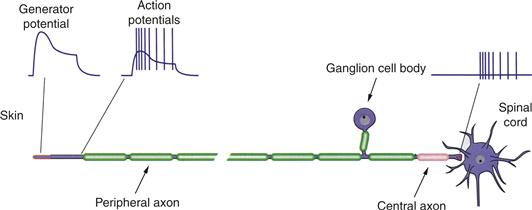

Neurons of the dorsal root ganglia (DRG) and trigeminal ganglia are the only routes by which mammals receive information from the periphery of the body and of the face. These are classic pseudo-unipolar cells. Each has a single axon that divides close to the cell body and sends separate branches to the periphery and into the central nervous system (Fig. 24.1). Under normal circumstances neurons in somatosensory ganglia receive no synapses. Although that situation can change with damage to the peripheral branches of ganglion cells, the normal lack of synapses means the cell body of a somatic sensory ganglion cell is a factory for all that must be made to keep its two axon branches functioning properly. Its major function—to keep a long axon healthy enough to avoid conduction failure—it does very well, as the incidence for conduction failures in a ganglion cell axon is near zero. Even where failures are reported, as in the small ganglion cell bodies of some vertebrate species, the effect appears deliberate and is tied to the difference in action potential shape seen in large and small cells.

Figure 24.1 A dorsal root ganglion cell is a pseudo-unipolar neuron with an axon that divides at a T-junction into a peripheral branch and a central branch. At the tip of the peripheral branch are receptor proteins that, through opening of cation channels, produce a depolarization called a generator potential. With sufficient depolarization, voltage-gated Na+ channels open to initiate action potentials. These action potentials are conducted down the axon and into the central branch that innervates second-order neurons in the spinal cord or in the medulla.

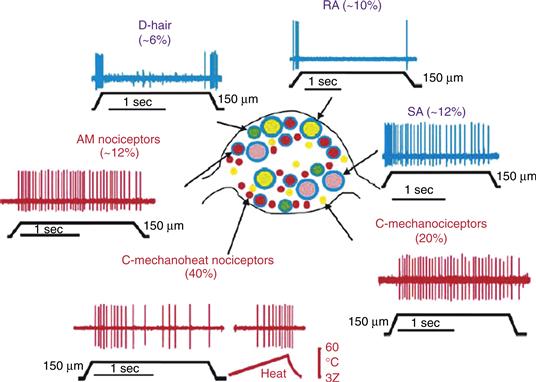

Neuronal cell bodies in somatosensory ganglia vary in size (Fig. 24.2). Although the details of size vary among species according to differences in body size, all species examined to date include two populations, one with somata at least half again larger than the cell bodies of the other. The population with smaller somata outnumbers those with larger somata by at least 2-to-1.

Figure 24.2 A somatosensory ganglion (center) is populated by a broad range of neurons that differ in size, gene expression and receptive field properties. Mechanoreceptors (in blue) differ in how they respond to a sustained stimulus. Rapidly adapting (RA) afferents of the glaborous skin and D-hair receptors or hair follicle receptors generate short bursts of action potentials at stimulus onset and offset. Slowly adapting (SA) afferents respond to a sustained indentation of skin with a prolonged series of action potentials. Nociceptors (in red) also vary in size and conduction velocity of their axons (Aδ vs. C) and in their response to noxious mechanical stimulation, such as a hard pinch. Some receptors respond specifically to this stimulus (AM nociceptors and C-mechanonociceptors) whereas others respond to a broad range of noxious stimuli (C-mechanoheat nociceptors). From Lewin and Moshourab (2004).

Peripheral branches of somatosensory ganglion cells enter peripheral nerves. In a mixed nerve, with both sensory and motor axons, the ganglion cells provide more than a fair share of the large, myelinated axons and all of the thinly myelinated and unmyelinated axons. Conduction velocities vary because of these differences in axon diameter and degree of myelination. Classic studies divide the sensory axons in human peripheral nerve into the following groups with conduction velocities in parentheses: Group I or Aα (70–120 meters/second), Group II or Aβ (40–70 meters/second), Group III or Aδ (12–36 meters/second), and Group IV or C (0.5–2.0 meters/second). These groups correspond to functional classes that carry proprioceptive, mechanosensory, thermoreceptive or nociceptive information from muscles, tendons and skin to the spinal cord (Table 24.1).

Table 24.1 Summary of Primary Afferent Fibers and Their Roles

What sets apart ganglion cells of the somatosensory system from ganglion cells of other systems is the requirement for double duty. Not only do they carry information into the CNS, but they also transduce all forms of somatosensory energy into a change in membrane potential. That means somatosensory ganglion cells are also receptor cells. To do both, ganglion cells insert two types of cation channels into the plasma membrane at the tips of their axons. One opens in response to a stimulus. Either it is physically tethered to peripheral tissue, and opens to an appropriate mechanical deformation, or it opens in response to changes in temperature, pH or the concentration of circulating factors that signal tissue damage. By way of these channels the tips of ganglion cell axons are depolarized to produce generator potentials. The second type of channel, voltage-gated Na+ channels, turns generator potentials into action potentials that the axon conducts along its length and into the central nervous system. The best evidence suggests the voltage-gated channels are present at the first node of Ranvier in myelinated axons and at a similar distance from axon tip in unmyelinated axons (Fig. 24.1).

Many Types of Somatosensory Receptors Innervate Skin and Deep Tissues

The modern tradition breaks up the axons of sensory ganglia into 13 varieties of receptors. These include 4 types of proprioceptors, 3 types of nociceptors, 2 groups of thermoreceptors (one each for cooling and warming), and 4 types of mechanoreceptors. That is a decidedly conservative point of view. At a minimum it leaves unmentioned the class of D-hair receptor or hair follicle afferent and it recognizes only the major types of nociceptors. Molecular and functional distinctions among the nociceptors alone add enough additional types to make the list approach 20. The point here is not to split peripheral receptors into the greatest number of types but to emphasize the unusual nature of somatosensory transduction: the system responds to a broad range of stimuli because it has so many receptor types.

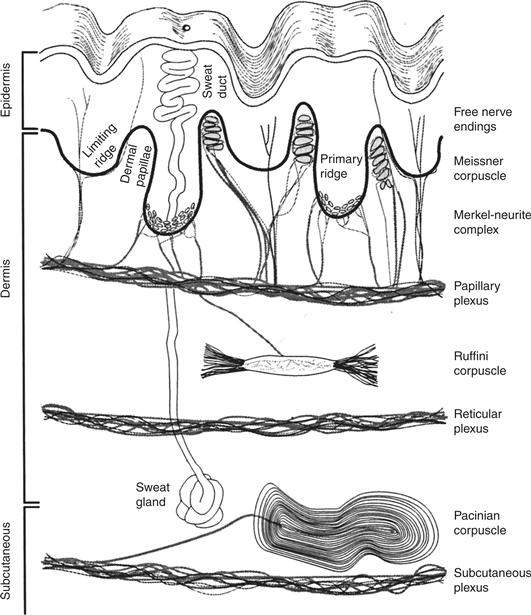

Mechanosensory Axons of Glabrous Skin Are Split into Four Types

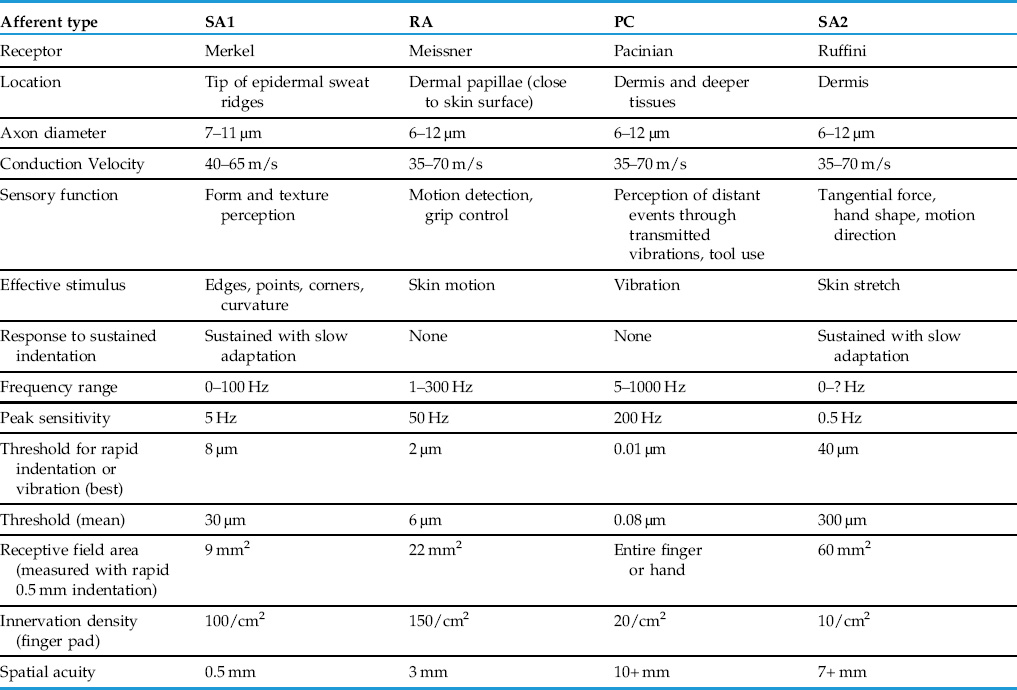

Four types of mechanosensory axons are found in the hairless or glaborous skin and immediately adjacent deeper tissues of the human body (Fig. 24.3). Whereas a decade ago it would have seemed a radical thought, we now recognize the four receptors are responsible for specific functions. These include peripheral events that lead to perception of form and texture (Johnson, 2001), detection of object slip leading to adjustment of grip, sensory feedback necessary for the use of tools, perception of vibration and perception of hand shape and limb position (Table 24.1).

Figure 24.3 Peripheral receptors of the hairless (glaborous) skin are present in dermis, epidermis and subcutaneous tissue. Superficial receptors at the dermis-epidermis border include the free nerve endings of nociceptors and thermoreceptors, the rapidly adapting afferents associated with Meissner’s corpuscle and the type I slowly adapting afferents that end as Merkel’s disks. Deep receptors include a rapidly adapting receptor enclosed by a Pacinian corpuscle and a type II slowly adapting afferent in some species. Those SAII afferents are associated with Ruffini corpuscles in domestic cats but appear to have some other arrangement in most of the human hand. SAII afferents are missing from the skin of macaques and mice. From Johnson (2002).

All mechanoreceptors conduct action potentials in the Aβ (type II) range, so no distinction can be made among them in that property. Rather it is in their response to the steady indentation of the skin that the difference among the four types becomes clear. Two types of afferents respond with a train of action potentials for as long as a blunt mechanical stimulus is applied to its receptive field. These are slowly adapting (SA) afferents, and they can be further divided into SAI and SAII types based on differences in spontaneous activity and in their sustained response to the applied stimuli (Fig. 24.2). Two other types of mechanoreceptor afferents are frequently called rapidly adapting (RA), or sometimes fast adapting or quickly adapting, because their response to a prolonged indentation of skin is a spike or two at onset of the stimulus, a single spike or two at offset and nothing in between. They, too, are split into two varieties, RA and PC, differing principally in their sensitivity and response to vibrating stimuli (see following). We should also point out some investigators object to the use of the term, adaptation, to describe this change in a mechanoreceptor axon’s response because, as we will see, it is not the axon that adapts but the tissue around it. Nevertheless, the terms rapidly adapting and slowly adapting are illustrative and are in common usage, so will we use them here.

Pacinian Corpuscles

The work of Iggo and Muir (1969) in the late 1960s established a consistent relationship among the four types of peripheral mechanoreceptor axons and the morphology of axon tips, or more properly of the axons’ relationship with nonneural cells. For three of the axons this structure-function relationship has held up well. The clearest example is that of the PC afferent, the tip of which ends as part of a Pacinian corpuscle. Unmistakable in its onion skin-like structure, the Pacinian corpuscle filters out low frequency mechanical stimuli such as sustained pressure applied to the skin (Fig. 24.3).

PC afferents are exquisitely sensitive to vibration. When the frequency of vibration approaches 200 cycles/second (Hz), a PC afferent responds to skin indentations of no more than 10 nm. Yet a single, steady indentation of the skin surface produces only a couple of spikes from these axons. Careful dissection of the connective tissue that surrounds the PC axon shows that the axon itself adapts to only a limited degree. It stops responding because the fluid-filled capsule around it carries the energy of a continually applied probe away from the axon tip. That closes the cation channels responsible for mechanical transduction. By contrast, repeated application of a mechanical stimulus, such as a tuning fork that vibrates at 200 Hz, produces a series of discrete transduction events and a series of action potentials. We can say with great confidence, then, that PCs respond to high-frequency vibration at even the smallest magnitude. This extreme sensitivity to vibration turns the PC afferent into a detector of remote events: they respond to the minute vibrations of the skin produced whenever we use tools, such as pencils, screwdrivers, and keys.

Meissner’s Corpuscles

Lower-frequency vibration, sometimes called flutter, produces a maximal response in RA afferents. As for PCs, the correlation between this type of response and the structure of the afferent axon and its surrounding tissue is consistent. Each RA afferent ends as a stack of broad terminal disks within a Meissner’s corpuscle composed of nonneural cells. Meissner’s corpuscles exist in dermal pockets, as close to the epidermis as any dermal structure can be (Fig. 24.3), and their density is extraordinary, approaching 50/mm2 in the index fingertip of a young adult. The result is an afferent very sensitive to even the slightest movement of skin, as happens when an object slides across the hand (Friedman et al., 2002). Yet every Meissner’s corpuscle has at least two RA axons curled around it, and every RA axon innervates between 20 and 50 separate corpuscles. This convergence of two or more RA axons to a single corpuscle and divergence of a single RA axon to many corpuscles leads to large receptive fields (5 mm2). So even though RA afferents are numerous and very close to the skin surface, their receptive field size and the filtering properties of the connective tissue capsule produce a response that is inappropriate for form and texture perception. RA afferents are responsible, instead, for the detection of objects slipping across the hand and fingers. They provide the sensory information that leads to the adjustment of grip force.

Merkel’s Disks

Of the two slowly adapting afferents, SAIs end in a manner that prompts no arguments. A single SAI axon breaks into several branches that end in several closely packed dermal ridges (Fig. 24.3). Each branch ends in a series of axon terminals and each terminal is enfolded by an epidermal Merkel cell, all of which produces a surface elevation called a touch dome.

Merkel cells contact the tips SAI afferents by what looks to be a chemical synapse, and vesicles in the Merkel cell are filled with neurotransmitters. When a gene mutation deletes Merkel cells early in embryonic development—before ganglion cell axons reach the skin surface—SAI responses fail to develop; when deletion occurs later in development, SAI responses persist. These data indicate Merkel cells play a fundamental role in the development of SAI afferents but contribute little to the transduction of mechanical stimuli.

SAI Afferents Are Responsible for Form, Texture, and Curvature

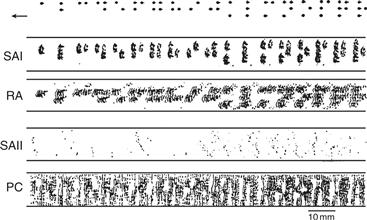

SAI afferents are the source of peripheral information used by the CNS to perceive form, texture, and object curvature. Form perception has been carefully studied by a combination of psychophysics and neurophysiology because the dimensions of form are readily quantifiable. When the performance of individual receptors on the surface of a monkey’s finger pad is compared with the performance of the monkey itself, only one type of afferent is found to be sensitive enough to account for an animal’s ability to discriminate the form of a mechanical stimulus. That receptor is at the tip of SAI afferents ending in Merkel’s disk. One example is seen in the response to the type of dots used in Braille (Fig. 24.4). Only the SAI afferents respond to the minute edges present in these embossed dots (6.0 mm high or greater) so accurately as to account for the ability a monkey or a human has in telling one pattern from the next.

Figure 24.4 Responses of peripheral axons to a Braille pattern of dots scanned over the surface of a human fingertip at a rate of 60 mm/s with 200-µm shifts in position after each pass. Dots represent individual action potentials. Only the response of the SAI afferents (Merkel disk receptors) follows the Braille pattern faithfully, whereas RA afferents and Pacinians (PC) produce a response that distorts the input. SAIIs display little response to this stimulus. Adapted from Phillips et al. (1990).

In contrast to tactile form, texture has relatively few dimensions (rough-smooth, hard-soft, and sticky-slippery are the most prominent), but they are difficult to quantify. Nevertheless, a series of careful studies has documented that for variations in roughness, only the response of SAI afferents matches human perceptual ability. That is, the variation in firing rates among SAI follows precisely the perception human subjects have of surface roughness. Much the same can be said for the detection of surface hardness. Only the response of SAI afferents can account for human perception of how hard or soft is the surface of an object scanned by the fingertips. In summary, a combination of physiological and psychophysical studies leads one to conclude that SAIs provide the central somatosensory system with all the information it needs to detect the shape, hardness, and the roughness of objects pressed or scanned across the skin.

SAII Afferents

A second slowly adapting afferent in human skin, the SAII afferent, differs from an SAI in the greater size of its receptive field, the reduced sensitivity to simple indentation of the skin, and the greater sensitivity to skin stretch. One surprising feature of these afferents is their less-than-universal presence across the few mammals that have been studied. Direct recordings from the peripheral nerves of humans and domestic cats show these afferents to be a commonly encountered feature of both species, but they are rarely encountered in monkeys or mice. Just as perplexing is the poor correlation between structure and function with this receptor. SAII responses in cats arise from axons terminating in skin as Ruffini endings. These structures were first described in human skin at the turn of the twentieth century, but a very recent study found true Ruffini endings in human skin very rarely and only in the bed of fingernails (Pare et al., 2003). And so it appears SAII responses over most of the human hand arise from some other interaction of mechanoreceptor axon and connective tissue sheath. A conservative conclusion from these findings is that an arrangement of nonneural cells, perhaps a classic Ruffini corpuscle in cats but another configuration in humans, leads to the cardinal feature of SAII afferents—namely, a robust response to skin stretch. That configuration could vary from one species to another and from one area of skin surface to the next, but in the end, the nonneural tissue serves as a mechanical filter. After subtracting from the activity of a SAII afferent any response to simple deformation of the skin, the nonneural tissue leaves behind an unambiguous response to anything that stretches the skin.

Hair Follicle Afferents

In addition to receptor types found in glaborous skin, hairy skin is innervated by a separate receptor, called the D-hair receptor or hair follicle afferent (HFA). It is the most sensitive receptor in hairy skin. The HFA threshold is said to be one-tenth that of any other afferent in mouse skin, and displacement of a hair follicle by as little as 1 µm produces robust responses in this population of receptors. Single afferents innervate more than one hair follicle and as a result, the receptive field of an HFA is large (>10 mm2 in mice). Unlike other mechanoreceptors, HFAs conduct action potentials in the Aδ range, which translates into a velocity of 20–25 m/s for humans but a much lower velocity in mice.

Receptor Density

A plot of SAI and SAII receptors along the human skin surface shows receptive field size and density vary by a factor of four in the short distance from the fingertip to the wrist. As is the case for other sensory systems, wherever receptor density declines, receptive field size ascends. This inverse variation in receptive size and density is reflected in the ability of a human subject to discriminate the two-dimensional shape of an object. Regions of high spatial acuity include the tips of the fingers and the face, whereas regions of low spatial acuity include the thigh and back.

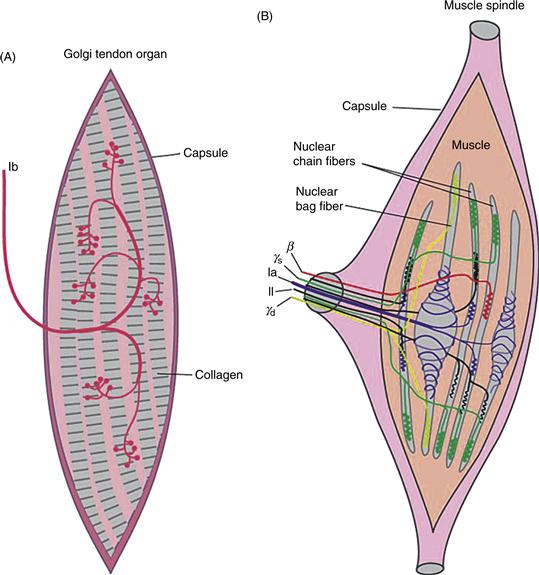

Muscle Spindles and Golgi Tendon Organs Are Proprioceptors

The most prominent receptors fulfilling the function of sensing position and movement are muscle receptors and tendon receptors. These two have in common their sensitivity to stretch and the large diameter of the axons that carry the receptors’ activity into the CNS. The manner in which they are arranged, however, makes all the difference in the world. Muscle receptors are arranged in parallel with the muscle fibers and as a result, these afferents respond when the muscle is stretched. As a common occurrence, muscle fibers stretch when load is added to them in the form of weight or resistance. The resulting stretch of the extrafusal or work muscle fibers produces a simultaneous stretch of the much smaller intrafusal muscle fibers. The intrafusal fibers have their own motor innervation and a sensory innervation from the largest diameter axons in a sensory nerve (Fig. 24.5). These sensory axons are called Ia afferents and they end in two configurations around the non-contractile portion of an intrafusal muscle fiber, where they signal the static and dynamic aspects of muscle stretch. A connective tissue capsule surrounds all of these—sensory axons, intrafusal muscle fibers, and motor axons—to form a muscle spindle. What the motor axons do to all this is simple to envision: by adjusting the contractile state of the intrafusal muscle fiber, they adjust the sensitivity of the muscle afferent. When the intrafusal fiber is contracted the spindle is at its most sensitive and when the intrafusal fiber is relaxed, the spindle is least sensitive.

Figure 24.5 Proprioceptive afferents. (A) Golgi tendon organs and afferent termination along collagen fibers of the tendon capsule. These afferents respond when the entire capsule is stretched, usually by overvigorous contraction of the muscle. (B) Muscle spindle afferents (Ia and II) terminate on the noncontractile portions of intrafusal muscle fibers. They are arranged in parallel with working muscle fibers and respond to stretch of the entire muscle. Specialized motoneurons (γ) provide the motor innervation of the intrafusal muscle fibers and control the overall sensitivity of the muscle spindle.

Much as muscle receptors are sensitive to muscle stretch, tendon receptors (referred to as Golgi tendon organs) are sensitive to tendon stretch and provide information about muscle force. Because tendons are arranged in series with the muscles, so too are tendon receptors. What stretches the tendon is muscle contraction. In this regard, muscle spindles and Golgi tendon organs signal opposite trends. Spindles fire when a muscle is relatively inactive and stretched whereas tendon organs fire when the muscle is most active and contracted.

Proprioception Involves More Than Proprioceptors

By a definition of proprioception as an awareness of the position of the body and limbs, the two most prominent proprioceptors are necessary but not sufficient. More than just muscle and tendon receptors are at work to provide us with information about limb position. The related sense of kinesthesia, or awareness of position of moving body parts, is equally complex. Often used interchangeably for position sense, these two are percepts that require the contribution of receptors in muscle, skin and joints as well as a sense of muscle exertion. Studies in the 1950s and 1960s focused on the contribution of joint afferents to a sense of limb position. Yet a series of findings in the 1970s made it clear that a sense of position survives joint removal; the joint afferents themselves respond only at the extreme limits of joint flexion. With no response in the usual, midrange of joint movement, these afferents could not signal position under most circumstances.

Studies of more recent vintage have dealt with muscle spindle afferents as a major source of the position signal. Since all muscles are organized as antagonistic pairs, contraction of one delivers a robust stimulus (muscle stretch) to afferents of the antagonistic muscle. From these sorts of inputs, limb position and movement would appear to require a simple neural computation. That position sense is significantly affected by stimulation, anesthesia and disengagement of spindle afferents adds weight to the argument that signaling limb position and movement requires these receptors. Perhaps the most convincing data are from studies of illusory movements produced by tendon vibration. This type of stimulus selectively activates spindle afferents and leads to the perception of limb movement when none has occurred. Illusory movement is muscle specific, so activation of arm flexors gives rise to the percept of an arm that has extended (a movement that normally produces activation of flexor muscle spindles). The illusion is so strong it gives rise to the Pinocchio effect: if arm flexor afferents are activated when a subject is touching his or her nose with an index finger, the nose itself is perceived to grow.

Only recently has proper attention been paid to the role of cutaneous receptors in position sense. SAII afferents, in particular, respond in a unique manner to any position a limb or digit might adopt. Particularly compelling is the role these skin stretch receptors play in signaling the position of fingers. For the hand and fingers, therefore, a conscious sense of position appears to arise from the cooperative activity of SAII afferents, muscle afferents and (at the extremes of movement) joint afferents.

Nociception

Nociceptors Respond to Noxious Stimuli

For most purposes, anything that has produced tissue damage or that threatens do so in the immediate future is defined as noxious; the type of axon that responds selectively to the noxious quality of a stimulus is a nociceptor. These are not pain receptors because nociception is not pain. Whereas nociception is a peripheral phenomenon that occurs when tissue has been or soon will be damaged, pain is a percept that requires regions of the CNS to become active.

All nociceptors end simply in skin and other peripheral tissues. These are usually described as free nerve endings because, unlike mechanoreceptive afferents, nociceptors do not end in a specialized capsule of nonneural cells. Nothing extraneuronal serves as a filter or buffer between the nociceptive axon tip and its immediate environment. The only thing that determines the response of a nociceptor, then, is the type of protein receptor and ion channel it inserts into its plasma membrane.

Nociceptors also differ from mechanoreceptors in how broadly the terminals of the peripheral axon branch as they reach target. Take the tip of the human index finger as an example. An individual SAI and SAII axon ends in a well-confined cluster of terminals over a distance as small as a few millimeters. Terminals of a single C fiber, by contrast, end over an area of more than a dozen millimeters. This is the first of several anatomical features along the nociceptive pathway that produce a much coarser spatial sense for pain than exists for mechanosensation. Only the simultaneous activation of mechanoreceptors as occurs with puncture wounds or damaging compression permits a person to accurately detect the location of a nociceptive stimulus.

The afferents that make up the nociceptive population can be subdivided into groups that are named by their axon conduction velocity (Aδ vs. C) and the response to noxious mechanical stimuli and noxious heat. Thus, an AM receptor conducts in the Aδ range and responds to intense mechanical stimuli, whereas a CMH receptor conducts in the C range and responds to both noxious mechanical energy and noxious heat. Other permutations of conduction velocity and response type are evident in the peripheral nerves of humans and other mammals, but these two are most common. They are frequently referred to as specific mechanical nociceptors and polymodal nociceptors.

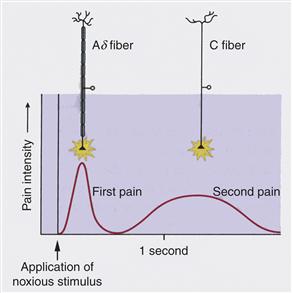

First and Second Pain

Afferents responding specifically to a mechanical stimulus (AM receptors) carry the most rapid signals into the CNS, whereas those responding to the broad range of noxious stimuli (CMH receptors) conduct action potentials more slowly. These are the peripheral components to the two very different qualities of pain perceived by humans (Fig. 24.6). First pain or epicritic pain is rapidly perceived and carries with it much that is discriminative. A person can quickly and with some ease figure out what has happened and where it has happened when he or she drops a heavy object onto a toe or touches a hot stove surface with a couple of fingers on the right hand. First pain is informative and the peripheral component of it is the population of Aδ nociceptors. What follows later is second pain or protopathic pain. This is agonizing pain that carries much less information about location or source of energy. Second pain is punishing pain that serves to change the behavior of a person. Its peripheral component is the population of C nociceptors.

Figure 24.6 The two classes of nociceptors that conduct action potentials in the C and Ad ranges are peripheral components for two types of pain. First pain carried by Ad axons reaches consciousness rapidly and is discriminative. Both the location and the subjective intensity of the stimulus can be judged with relatively good precision in first pain. Second pain, in contrast, is much slower and is agonizing pain, with greatly reduced discriminative value.

Two varieties of C nociceptors are found in mammalian skin. One variety is characterized by the presence of fluoride-resistant acid phosphatase (FRAP) in its cytoplasm and cell-surface glycoproteins recognized by the isolectin I-B4 and the monoclonal antibody LA4. Because none of these proteins is known to contribute to the physiological features of this C fiber type, their presence is currently a convenient feature that allows anyone studying them to recognize them. The situation is very different in the second type of C nociceptor. Present in its cytoplasm are two neuroactive peptides: calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) and substance P. These play major roles in the function of the peptide-containing type of C nociceptor.

The Axon Reflex

Release of neuropeptides from the second type of C nociceptor is responsible for the axon reflex. Injury to the skin surface is often well confined, as happens with a paper cut, for example. Yet within a short time of that injury, tissue surrounding the cut becomes reddened, in what is referred to as flair, and edema or swelling sets in as the tissue fills with fluid. Most importantly, the region surrounding a punctate wound becomes painful to touch even though it is outside the zone of direct damage.

Recall that an individual C fiber terminates over a wide area in skin, and so it is very likely that a punctate wound directly affects only a fraction of all that fiber’s many branches. Action potentials generated at those directly affected branches invade all the peripheral branches, as well as the parent axon that conducts the signal to the CNS. At all the peripheral terminals, substance P and CGRP are released onto two principal targets: the smooth muscle surrounding peripheral blood vessels and histamine-rich mast cells. By causing the arterial smooth muscles to relax, the peptides increase the flow of blood into the damaged tissue and produce a flow of water and electrolytes out of capillaries and into extracellular space. This process is referred to as extravasation. Histamine released from mast cells leads to a pronounced inflammatory response. All of this is important for the infiltration of damaged tissue with cellular elements that will protect against infection and promote repair. Yet what is most obvious about the axon reflex is the much greater sensitivity of the tissue surrounding a wound to anything that might be noxious. This primary hyperalgesia is a direct result of the axon reflex. It occurs because the protein receptors inserted into nociceptive axons are sensitive to chemical changes produced by that reflex (Sandkiller, 2009).

Both the histamine released by mast cells and the edema resulting from extravasation affect the response of nociceptors. Histamine’s effects are more selective, as only a subclass of the most slowly conducting C fibers insert histamine receptors into the membranes of their axon terminals. A considerable body of evidence suggests these are peripheral receptors whose activity leads to the unpleasant percept of itch. A parallel system for itch that operates independently of histamine release has been discovered recently but the population of afferents involved is not yet known.

Edema causes a general reduction in pH of extracellular fluid from 7.4 to below 6.0. A general feature of protein receptors inserted into nociceptive axons is their sensitivity to the concentration of H+. Through this sensitivity to pH, activation of one branch of a C fiber leads to increased sensitivity of all its branches and all neighboring nociceptors to noxious stimulation. At least some of those neighboring nociceptors are likely to be silent nociceptors, so named because they are unresponsive to intense mechanical stimulation under normal circumstances. When activated by changes in pH or the presence of factors that signal the presence of tissue damage, the silent nociceptors become responsive to noxious stimuli.

Chemical Sensitivity of Nociceptors

Two of the most powerful pain-inducing chemicals that can be delivered to a human observer are natural products of tissue damage. They are lipids of the prostaglandin family and the peptide bradykinin. Prostaglandins are derivatives of the membrane fatty acid, arachidonic acid, which is itself a major component of the lipid bilayer. Damage to tissue and the resulting disruption of cell membranes releases arachidonic acid into extracellular fluid. The enzyme cyclo-oxygenase (COX) breaks down arachidonic acid to form prostaglandin. Inhibitors that target COX are referred to as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS) and they include both aspirin and ibuprofen. Their popularity is a powerful indication of effectiveness in suppressing pain by interfering with the production of prostaglandins.

Nociceptor Proteins

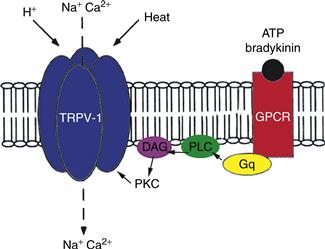

Detection of noxious heat occurs by way of channels that are members of the transient receptor potential (TRP) family. Two members of the TRPV class—they are referred to as TRPV1 (Fig. 24.7) and TRPV2—pay particularly important roles in nociception (Tominaga et al., 1998). The V in the channel’s name refers to its sensitivity to vanilloids, the active ingredients of chili peppers. TRPV1 is a nonspecific cation channel with approximately ten times more permeability to Na+ than to Ca2+. Like other members of the TRPV subfamily, TRPV1 is a molecular thermometer that opens in response to increased temperature. It has a threshold of 42o C. TRPV2 channels, by contrast, open only when skin temperature reaches 50o C. Although they are primarily detectors of noxious heat, nociceptors with TRPV1 channels are typically polymodal (they respond to other noxious stimuli), in part because of the TRPV1’s properties and in part because these afferents express other receptor proteins. Because H+ directly gates TRPV1 channels, any reduction in pH (the acidosis that accompanies tissue swelling) comes to depolarize these afferents. Other channels, the Acid Sensing Ion Channels (ASICs), also open in response to an increase in H+ concentration. One of these, referred to as ASIC-3, is especially sensitive to the presence of lactic acid and, therefore, is a prime candidate for a receptor of ischemic pain in cardiac muscle.

Figure 24.7 The receptor protein, TRPV1, provides a nociceptor with the ability to respond to many noxious stimuli. In addition to heat, TRPV1 is directly gated by a reduction in pH (afferent of H+) produced in response to tissue swelling. Either or both opens a nonspecific cation channel that, through an influx of Na+, depolarizes the nociceptor axon. Circulating agents that signal the presence of tissue damage (ATP and bradykinin) bind to a G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR). Through a series of steps PKCε is activated and TRPV1 subunits are phosphorylated, leading to a sensitization of the receptor. One result of this cascade is an opening of the cation channel at body temperature.

Two other proteins, both G-protein coupled receptors, broaden the response of polymodal nociceptors to include anything that produces tissue damage. One is a receptor for two molecules—bradykinin and ATP—released when the plasma membranes of cells are damaged. Their binding to plasma membrane receptors sets up an intracellular cascade that lowers the threshold temperature at which TRPV1 channels open. As that threshold descends to normal body temperature, TRPV1 channels open without any thermal stimulus at all and initiate action potentials in nociceptor axons. Finally, most polymodal nociceptors express GPCRs that bind prostaglandin and drive open an unusual population of Na channels. This, too, provides the afferents with a depolarizing stimulus when tissue is damaged.

One major outstanding question is the nature of the channel that opens in response to noxious (high-threshold) mechanical stimulation, such as a hard pinch. The same question exists for the low-threshold mechanically gated channel in SA and RA afferents, in proprioceptors, and in other cells, such as hair cells of the inner ear. Whereas common wisdom has long thought the somatosensory mechanoreceptors to be members of either the Epithelial Sodium Channel (ENaC) family or the TRP superfamily, very recent work suggests they are part of a novel group that has been dubbed Piezo. Caution is advisable, however, because the search for a mechanically gated channel has had its fair share of blind alleys and false starts.

CNS Components of Somatic Sensation

The central paths taken by large diameter afferents and small diameter afferents tell two stories worth attention. The first is that the path for mechanosensation and proprioception is separate and largely distinct from the path for nociception, thermoreception, and itch. These separate paths continue through the CNS to the cerebral cortex and represent one of the clearest divisions of labor seen in any sensory system. The second story is seen in the many regions of the CNS contacted by each population of axons. Here the lesson repeats a statement made at the beginning of this chapter: the somatosensory system has many tasks to perform, from the input side of motor reflexes to the higher-order functions of perception, comprehension, and emotion. To accomplish them, mechanosensory/proprioceptive and nociceptive/thermoreceptive axons send information along several pathways, performing separate functions.

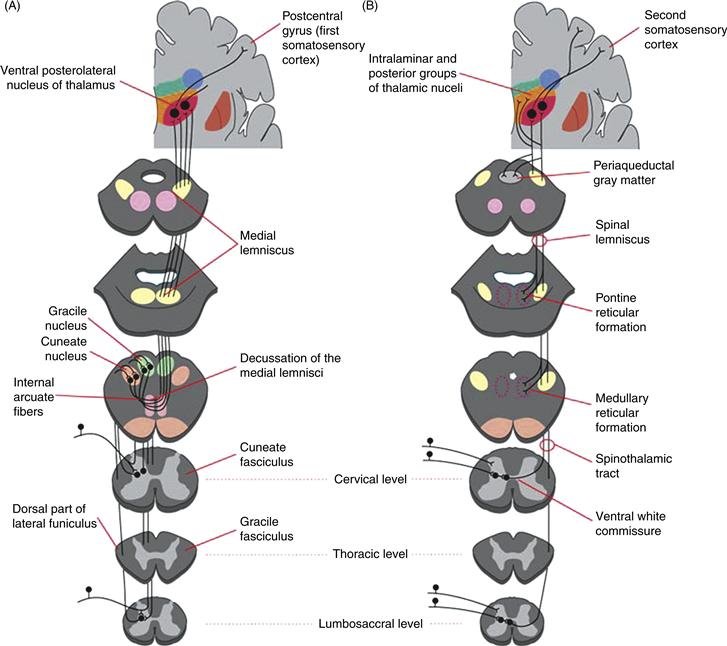

An Outline of Ascending Paths to Perception

Primary afferents in the somatosensory system terminate on second-order neurons in either the spinal cord (nociceptors and thermoreceptors) or medulla (mechanoreceptors and proprioceptors) (Fig. 24.8). Second-order neurons in the spinal cord and medulla send their axons across the midline to terminate in thalamus. Convergence is kept to a minimum so that second-order mechanosensory and nociceptive neurons end in separate nuclei and subnuclei of the thalamus. In addition, axons of particular submodalities (e.g., muscle spindle afferents vs. cutaneous afferents) end in different subnuclei of the thalamus. The major thalamic nuclei involved are the various parts of the ventral posterior complex (referred to as ventral caudal in human studies). The lateral and medial subnuclei of VP, logically named VPL and VPM, are the recipients of discriminative inputs from the body and face, respectively. Both innervate the first somatosensory cortex (SI) and a third subnucleus, VPI, sends its axons to the second somatosensory area (SII).

Figure 24.8 Anatomy of ascending somatosensory paths. (A) Organization of the dorsal column-medial lemniscal system from entry of large diameter afferents into the spinal cord to the termination of thalamocortical axons in the first somatosensory area of the cerebral cortex. An obligatory synapse occurs in the gracile and cuneate nuclei, from which second-order axons cross the midline and ascend to the ventral posterolateral nucleus of the thalamus (VPL) by way of the medial lemniscus. (B) Organization of the spinothalamic tract and the remainder of the anterolateral system. Primary axons terminate the spinal cord itself. Second-order axons cross the midline and ascend through the spinal cord and brainstem to terminate in VPL and other nuclei of the thalamus. Collaterals of these axons terminate in the reticular formation of the pons and medulla.

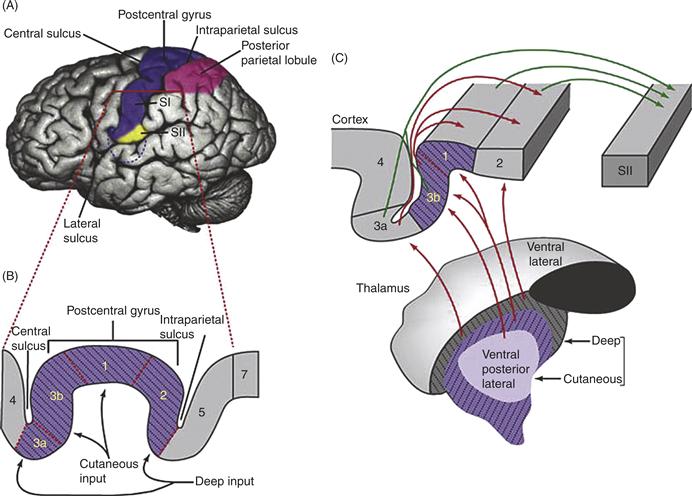

SI and SII are recognized in the cerebral cortex of all mammals that have been examined (Fig. 24.9). Yet the organization of each appears to vary considerably across that class. If we take human cerebral cortex as a starting point, SI is traditionally divided into four structurally distinct areas named (from rostral to caudal) areas 3a, 3b, 1, and 2. The same is seen for the best-studied genus of monkeys, the macaques. What stands out in the organization of these four areas is the combination of serial and parallel processing. Parallel processing is seen in the types of thalamic neurons that innervate each area and the receptive field properties displayed by those cortical neurons. Areas 3b and 1 are most often characterized by the response of neurons to cutaneous inputs, SAs and RAs, whereas neurons in area 3a are found to respond exclusively to stimulation of deep receptors and neurons in area 2 respond to both.

Figure 24.9 The first somatosensory cortex of humans and other primates is an amalgam of four areas, each of which has a complete map of the body surface. (A) SI and SII are located posterior to the central sulcus. (B) SI is shown at higher magnification. Areas are numbered according to the original scheme by Brodmann as areas 3a, 3b, 1, and 2 (from rostral to caudal in the postcentral gyrus). (C) Thalamic input from the core of VPL and VPM carries cutaneous mechanosensory information to areas 3b and 1, while a parallel route from the shell of VPL and VPM carries deep (e.g., muscle spindle) information to areas 3a and 2. Intracortical connections from area 1 to area 2 make up a route by which cutaneous information also reaches area 2. As a site of convergent deep input from thalamus and cutaneous input from area 1, area 2 is the most likely location in which a complete proprioceptive map emerges.

Serial processing of information is evident in both the physiology and connectivity of these areas. Area 3b is much more richly innervated by VPL and VPM than any of the other three areas of SI and, in terms of its structure and connectivity, appears much more of a primary sensory area. Comparative studies suggest that area 3b of rhesus monkeys and humans is in most ways equivalent to all of SI in other mammals and so this area is often referred to as SI Proper. The principal outputs of area 3b are directed caudally to areas 1 and 2; and in a similar fashion, area 1 sends its own rich set of axons to area 2. From these considerations, a hierarchy emerges, with area 2 at something of a pinnacle, in that it receives a direct deep receptor input from the thalamus, indirect deep input from 3a and an indirect cutaneous input from areas 3b and 1.

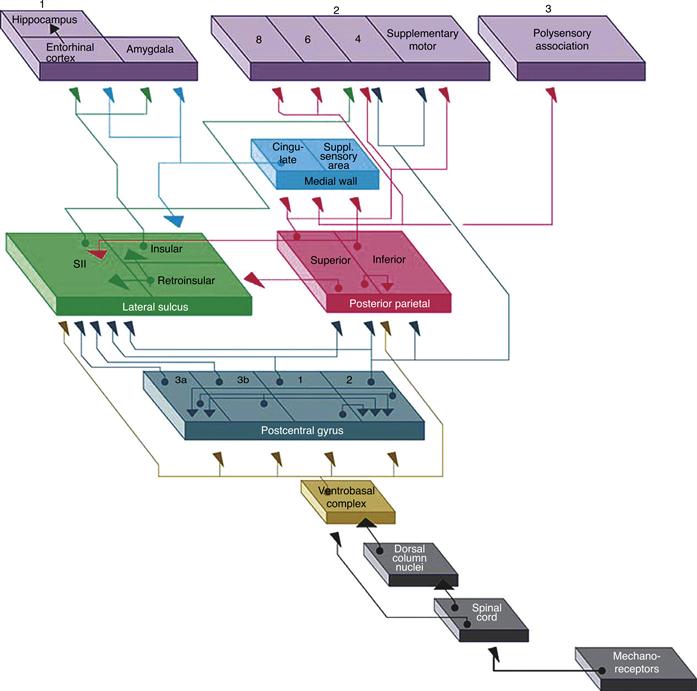

The output of SI as a whole is in two directions (Fig. 24.10):

1. A ventral path to SII and from there to the caudal insula, to areas of the temporal lobe, and to premotor and prefrontal cortical areas. Eventual convergence of somatosensory, auditory, and visual information in the medial temporal lobe is viewed as the path toward shape and form processing. This ventral path is vital for inserting new information into declarative memory and accessing established memories for comparison with ongoing events.

2. A dorsal path to superior parietal lobule, providing areas in that lobule with somesthetic information for control of voluntary movements, selective attention, and information about how to perform different tasks, sometimes known as the “how” pathway.

Figure 24.10 Schematic representation of the path taken by mechanoreceptor input to eventually reach three cortical targets. All relevant information reaches the ventrobasal complex and most is relayed to the areas of SI. From there, by steps through SII and the posterior parietal areas, somatosensory information reaches (1) the limbic system (entorhinal cortex and hippocampus), as a means for becoming part of or gaining access to stored memories; (2) the motor system (primary and supplementary motor cortex), where the continuous sensory feedback onto the motor system occurs; and (3) the polysensory cortex in the superior temporal gyrus, in which creation of a complete and abstract sensory map of the external world is thought to occur.

With these essential elements in mind, we will consider separately the paths for mechanosensation and nociception from the entry of primary afferents into the spinal cord to the areas of cortex in which the elements of sensation are brought together into a perceptual whole.

The Path for Mechanosensation for the Body

Dorsal columns are the principal routes for spinal mechanoreceptor axons. All axons of sensory ganglion cells enter the CNS by way of dorsal roots and the trigeminal nerves. At a gross level the spinal cord is segmented by the existence of separate dorsal root ganglia. Because the peripheral tissue innervated by any one dorsal root ganglion is restricted, the entire innervation of the body surface can be seen as a series of overlapping bands. These are the dermatomes. As a practical matter, then, a mechanical stimulus applied to a restricted region of the body surface leads to action potentials conducted in one or at most two dorsal roots.

Mechanosensory and Nociceptive Axons Enter the Cord along Different Paths

The dorsal roots divide after they have penetrated the dura mater but before they are have entered the spinal cord itself. A medial division of large diameter, heavily myelinated axons enters at the dorsal funiculus of the cord, and the majority of those axons turn at right angles after they have entered the cord and ascend toward the brain. From level T7 of the cord to the terminal coccygeal segment, the large diameter axons enter one fiber tract called the gracile fasciculus. And as they do so they stack up as thin sheets with the earliest entering axons (coccygeal) occupying the most medial part of the funiculus and the last entering (7th thoracic) occupying the most lateral part. That same medial-to-lateral pattern continues with large axons that enter from T6 up to the first cervical segment but at those levels the axons form a separate fasciulus, called the cuneate fasciculus. Together the gracile and cuneate fasciculi are called the dorsal columns. The orderly pattern established by the axons of the dorsal columns as they ascend means there is a body map or somatotopy to the ascending mechanosensory system. Large diameter axons ascend on the same side of the spinal cord as the one they entered to reach the lowest levels of the medulla.

Dorsal Column Nuclei

In a path toward sensory perception, the majority of axons in the dorsal columns ascend to reach the dorsal column nuclei at the junction of the spinal cord and medulla. The dorsal column nuclei are neither simple nor homogeneous. At the grossest level, each nucleus is divided into at least three regions in which axons of different mechanoreceptors terminate separately. Neurons receiving muscle spindle inputs are sufficiently distinct in some species to be given their own name: nucleus Z. All of this serves to accent the role played by subcortical somatosensory nuclei in keeping segregated the input from different functional classes of receptors.

Despite an anatomical convergence of primary afferents onto single neurons of the dorsal column nuclei, convergence and comparison of receptor input appears minimal. The coupling between a single neuron in the gracile or cuneate nucleus and a single afferent axon is extremely tight (Rowe, 2002). As a result of this coupling, a single action potential in the afferent axon reliably produces an action potential in the postsynaptic cell. That phenomenon is seen for RA, PC, and SAI afferents of the glabrous skin and hair follicle afferents of the hairy skin. These findings indicate that for a neuron in the gracile and cuneate nuclei, receptive field locations, sizes and properties are a matter of which primary afferent innervates that neuron.

The Lateral Cervical Nucleus

A cluster of mechanosensitive relay neurons starts in the dorsal horn at cervical segments 1 and 2 and extends into the caudal one-third of the medulla. This is called the lateral cervical nucleus. Innervated by mechanosensory neurons in the dorsal horn throughout all segments of the spinal cord, the neurons in the lateral cervical nucleus display predominantly cutaneous receptive fields that cover large patches of hairy skin and usually some part of glabrous skin. Most axons of cells in the nucleus decussate immediately and reach the contralateral VPL by way of the medial lemniscus. In the VPL, the cervicothalamic axons responding to low-threshold mechanical stimulation of skin or hair appear to converge with axons that arise in dorsal column nuclei. Unlike other nuclei of the somatosensory system, the lateral cervical nucleus is an inconstant feature of the mammalian nervous system. Whereas it is a robust part of the spinal cord and medulla in rodents and carnivores and has been found consistently in nonhuman primates, it is present in only half the humans studied and is well defined in very few of them. Comparison across species also shows a marked difference in the density of cervicothalamic terminations in the VPL, with the density in cats far exceeding that in rhesus monkeys. These findings lead to the assumption that functions parceled out to the lateral cervical nucleus in rodents and carnivores are sequestered in the dorsal column-medial lemniscal system of primates, and particularly of humans.

Thalamic Mechanisms of Somatic Sensation

Segregation of Place and Modality Continues in Thalamus

Medial lemniscal axons terminate on large neurons of the VPL and VPM. As in the dorsal column nuclei, the synaptic means to generate lateral inhibitory influences exists in the thalamus, but evidence for robust lateral inhibition is seldom found in these nuclei. Where inhibition has been detected, its strength across the neuron’s receptive field matches that of the excitation so that the region of greatest inhibition is also the region of greatest excitation. Missing from this stage of somatosensory processing, then, is the synaptic means to produce contrast, by which activity produced by stimulation of one spot on the skin surface is compared with activity produced by stimulation of surrounding regions.

Neurons in the VPL and VPM display a cluster of features labeled as lemniscal properties. Static lemniscal properties are place and modality specificity. Thalamic circuits maintain these features much as they exist in the lemniscal afferents themselves. As a result, mixing of inputs is avoided in the thalamus and the specific properties of where on the body surface something has occurred and what exactly has occurred remain anatomically distinct. Dynamic properties characteristic of these cells include the ability to follow a rapid train of stimuli. Here the synaptic organization of the thalamus favors the ability of a thalamic neuron to behave much like the axon that innervates it.

Anatomical and physiological studies demonstrate that as lemniscal afferents terminate in the VPL, they do so as clusters of axon terminals elongated in the rostro-caudal dimension. They are referred to as rods. Rods appear to be the major organizing principle to somatosensory thalamus, as lemniscal axons carrying information of the same type (e.g., SAI input) from the same part of the body terminate in a rod-like formation. On the output side, thalamocortical neurons that send axons to a 1-mm-wide patch in SI occupy the same sort of formation. Thus, thalamic rods are the anatomical basis for the most salient feature of somatosensory thalamus: the strict segregation of place- and modality-specific responses.

The Path from Nociception to Pain

Spinal Cord Pathways

In stark contrast to the pattern of input by mechanosensory axons, nociceptive axons terminate in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. These lightly myelinated and unmyelinated axons enter the cord by way of a lateral division of the dorsal root and divide to send branches up and down the cord for a segment or two. The tract they form is a cap on the surface of the dorsal horn called Lissauer’s tract. Nociceptive axons terminate, therefore, on dorsal horn neurons across four or five segments, and a single dorsal horn neuron is innervated by nociceptors that cover a broad swath of the body or limb surface. Second-order neurons innervated by the nociceptive axons give rise to axons that decussate and ascend in the anterolateral quadrant of white matter to reach the brainstem and thalamus.

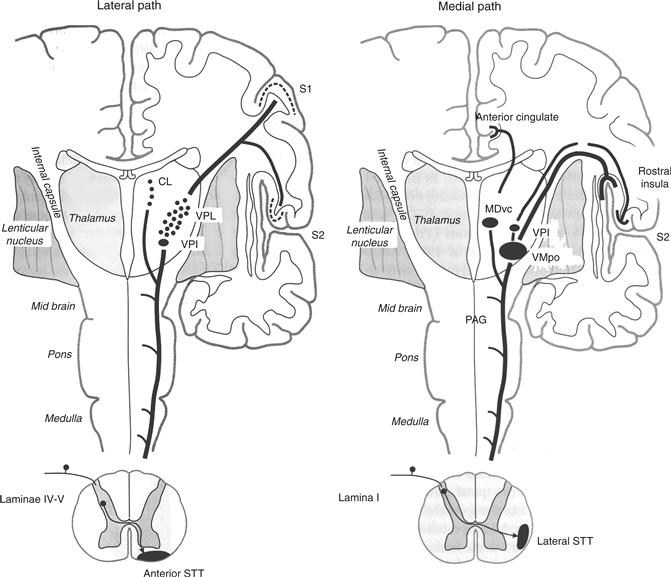

Spinal cord circuits for nociception form two ascending routes with distinct functions (Fig. 24.11). Recall that the peripheral basis for first and second pain is the division of nociceptors into relatively fast-conducting Aδ axons and slow-conducting C fibers (Braz et al., 2005). Yet the discriminative versus agonizing components of pain is a CNS construct, produced by the difference in central circuits driven by Aδ and C fibers. To appreciate that difference, it is best to start with the population of spinothalamic neurons.

Figure 24.11 The medial path taken by spinothalamic neurons in lamina I (driven by C fibers) differs from the lateral path taken by neurons in laminae IV and V (driven by C and Aδ nociceptors and Aβ mechanoreceptors). Anterior spinothalamic tract axons are given off by the deeper neurons and terminate in lateral thalamus (VPL and VPI and the centrolateral nucleus). Lateral spinothalamic tract axons given off by lamina I neurons innervate medial thalamus, including the ventral caudal division of the mediodorsal nucleus (MDvc) and a region in posterolateral thalamus. In this figure, the region is labeled a separate, nociceptive/thermoreceptive-specific nucleus called VMpo, but several lines of evidence indicate lamina I neurons also innervate VPL and VPM, as well as VPI. From this varied thalamic innervation, nociceptive information reaches SI and SII for discriminative aspects of pain and temperature and the anterior cingulate and rostral insula for the affective, punishing aspects of pain.

Spinothalamic Neurons

Spinal cord neurons that directly innervate thalamus (therefore, spinothalamic neurons) occupy several laminae in rhesus monkey spinal cord. The major populations, however, are found in the most superficial layer of dorsal horn (lamina I) and a second region deeper in the dorsal horn (lamina V). Nociceptive innervation of these two populations differs fundamentally. Lamina I neurons are innervated predominantly by C fibers, both directly and indirectly by way of excitatory interneurons in the immediately adjacent superficial half of lamina II. Theyalso receive an indirect innervation from Aδ fibers by those same interneurons and can be thought of as nociceptive-specific cells. Lamina V neurons, on the other hand, are innervated predominantly by Aδ fibers that end deep in lamina II on a population of excitatory interneurons. Many of these deeper spinothalamic neurons also receive a convergent input from mechanosensory axons (Aβ axons). Because they respond to both nociceptive and mechanosensory stimulation, these neurons are often referred to as wide dynamic range cells.

Ascending Paths to the Thalamus

Axons from both lamina I neurons and laminae IV/V neurons decussate and enter fiber tracts in the anterolateral quadrant of spinal cord, but the tracts they enter differ from one another in location and termination (Fig. 24.11). Neurons of laminae IV and V enter the anterior spinothalamic tract and terminate in lateral parts of the thalamus, including the VPL and VPI, and an intralaminar nucleus, the central lateral nucleus. The innervation of ventral posterior thalamus does not mean both nociceptive and mechanosensory information converge in the thalamus. The two remain segregated as medial lemniscal axons terminate on groups of large neurons, whereas spinothalamic axons innervate clusters of smaller neurons. Response properties of the smaller neurons in the VPL are much like those of the wide dynamic range neurons that innervate them, both in the type of stimuli to which they respond and the size of their receptive fields.

Nociceptive specific neurons of lamina I enter the lateral spinothalamic tract and terminate in several nuclei of the thalamus, including two that receive few deep lamina inputs (Fig. 24.11). Targets in which convergence of lamina I and lamina V inputs are strongly suspected or known to occur include the nucleus of the ventral posterior complex. Although the most compelling data in support of convergence has been reported for VPI, several careful studies have documented termination of lamina I inputs in the clusters of small neurons in VPL and VPM. This represents what has become a traditional view of the nociceptive pathway, that discriminative pain is driven by nociceptive inputs to both lamina I and lamina V, through a relay in the ventral posterior nuclei, and that nociceptive information reaches SI and SII (Perl and Kruger, 1996).

Outside the ventral posterior complex are two sites of spinothalamic terminations predominantly from lamina I (Fig. 24.11). One of these is a subnucleus of the mediodorsal nucleus (Mdvc) in which spinothalamic terminations are surprisingly rich. The other is posterior to the classically drawn borders of VP and includes the medial nucleus of the posterior group (POm). Neurons in this region are innervated by spinothalamic axons and display the same chemical signature (immunoreactivity for the calcium-binding protein, calbindin) as spinothalamic-recipient neurons of VPL and VPM (Craig and Dostrovsky, 1999).

Considerable disagreement exists about the spinothalamic innervation in posterolateral thalamus of monkeys and humans. One part of the disagreement deals with the proportion of lamina I afferents that end inside the bounds of the VPL and VPM and those that end caudal and medial to it. A conservative reading of the literature leads us to recognize spinothalamic innervation of four regions, each with its own cortical target. Spinothalamic terminations in the VPL and VPM are relayed to SI and those in VPI to SII. Together, they can be seen as a lateral path to first or discriminative pain. A second medial path to anterior cingulate by way of MDvc and to the insula by neurons of VMpo appears to be the central route for second or punishing pain.

SI and Pain

Nociceptive responses in SI have been difficult to record, and where neurons responding to noxious stimuli have been encountered, their location (e.g., area 3a) has not been easy to fit into a general scheme of what these areas do. Nevertheless, ablation studies in monkeys show SI’s involvement in pain perception, and studies of human cerebral cortex regularly show that SI responds to stimuli judged to be painful. Perhaps the most compelling story can be told for area 1 of SI in monkeys, where evidence exists of clustered organization for nociceptive neurons (Kenshalo et al., 2000). Yet these neurons do not form columns. They are largely confined to layer IV of that area and are intermixed with mechanosensory neurons. These data suggest that nociceptive and mechanosensory inputs converge in area 1, perhaps as a means to accurately locate the source of pain.

The Human Axis of Pain

Functional imaging studies of the human brain indicate four areas of cerebral cortex are active during the application of a painful stimulus. Activation of SI and of SII occurs as part of a discriminative component to painful stimuli. A subject’s ability to report the location and to grade the intensity of a stimulus is correlated with activity in these areas. Two other areas appear tied to the cognitive and emotional content of pain. These are the rostral half of the anterior cingulate gyrus and the rostral insula, both of which display elevated activity during the anticipation of painful stimuli and the infliction of pain on a loved one (empathetic pain). And it is these areas that show a reduction in activity when the administration of a placebo produces reports of lessened pain. As a group, then, studies of the cortical representation of pain point to a distributed network of four main areas (SI, SII, rostral anterior cingulate, and rostral insula) in which the noxious stimulus applied to some peripheral region becomes a painful sensation with both discriminative and punishing components.

Nonperceptual Elements of Nociception

Several paths are taken by first- and second-order nociceptor axons that reach neither spinothalamic neurons nor regions of the thalamus. Targets of these axons include spinal interneurons that mediate the withdrawal and crossed-extensor reflexes; the pontine reticular formation, where the startle reflex is generated; and the midbrain periaqueductral gray (PAG) as a means for controlling pain. The last of these is a well-studied mechanism. Neurons of the PAG are innervated by second-order nociceptive neurons in laminae V. They provide PAG neurons with an indication of the source and intensity of nociceptive input. By way of a relay from serotonin neurons in nucleus raphe magnus and norepinephrine neurons in the locus coeruleus, activity in PAG drives a population of interneurons in the lamina II of the spinal cord. Two characteristics of those interneurons are worthy of consideration. First, they end not only on the populations of spinothalamic neurons but also on the axon terminals of C and Aδ axons. Through postsynaptic inhibition these inhibitory interneurons are able to suppress the response of spinothalamic cells and through presynaptic inhibition they are able to suppress release of the neurotransmitter, glutamate, from primary nociceptive afferents. The combination of pre- and postsynaptic inhibition reduces activity in the population of spinal neurons that carries nociceptive information to the brain. Second, the inhibitory neurons release the pentapeptide, met-enkephalin as a neurotransmitter. Met-enkephalin is an opioid peptide that binds to a member of the opiate receptor family. Its actions are mimicked by the administration of morphine and synthetic opiates accounting for at least part of the analgesic properties those compounds possess.

Pain is such a rich experience with an obvious impact on the well-being of a person that unusual phenomena associated with pain have been studied in considerable depth. Among the best studied are referred pain, secondary hyperalgesia/allodynia, and phantom limb pain. Each has been explained by referring to the circuitry and chemistry of normal nociceptive processing. Referred pain is the experience in which noxious stimuli in the viscera (e.g., ischemia of cardiac muscle) is felt as pain in a peripheral location such as the shoulder. A classic explanation for referred pain notes the widely branching nature of C and Aδ fibers as they enter the cord, so that lamina I neurons innervated by nociceptors of the shoulder are also innervated by nociceptors of the pericardium. When the latter are driven to fire a series of action potentials the percept is one of a more common occurrence, shoulder pain.

Central or secondary hyperalgesia and allodynia are related phenomena that occur in response to synaptic plasticity at the level of the spinal cord. Secondary hyperalgesia is a phenomenon in which a greater degree of pain is felt upon application of a noxious stimulus to a place other than the wound site. Allodynia, by contrast, is the perception of pain when the stimulus, itself, is not noxious. Each occurs when the application of an intense or prolonged noxious stimulus leads in spinal circuits to a rearrangement in synaptic strength, much like long-term potentiation. With secondary hyperalgesia, the potentiation is homosynaptic, leading to a greater postsynaptic response in spinal neurons to a noxious stimulus. Plasticity with allodynia is thought to be heterosynaptic. Under normal circumstances, activity in Aβ fibers to a benign mechanical stimulus (e.g., the movement of a cotton swab across the skin) modulates a response to noxious stimuli but fails to drive spinothalamic cells. Yet when the synapses formed by the Aβ fibers are potentiated in response to an intense or prolonged barrage of C fiber activity, spinothalamic neurons are driven by that mechanical stimulus. The result is perception of pain where only nonnoxious mechanical stimulation has occurred.

Unlike allodynia, phantom limb pain appears to involve synaptic plasticity at each of several levels in the somatosensory system. Removal of a digit or limb in experimental animals and in humans leads to a robust functional plasticity. Surgical removal of digits produces a short-lived silent zone in the somatotopically appropriate part of SI, but quickly thereafter, the previously silent region becomes responsive to tactile stimulation. The newly acquired response is to adjacent body parts, as the activity evoked in neighboring receptors fills in the zone where the cortex had been silent. Subsequent work has shown that following amputation of a digit or limb, this process of filling in takes place through synaptic changes in the spinal cord, medulla and thalamus, as well as in cerebral cortex. It is assumed that phantom limb pain works much the same way. Thus, stimulation of the shoulder and chest in amputees drives regions of cerebral cortex that had been responsive to stimulation of an arm prior to its amputation. The result is the percept of arm pain even in the absence of an arm (Box 24.1).

Box 24.1 The trigeminal system

Mechanoreceptive, nociceptive, and thermoreceptive afferents for the face have their cell bodies in the pair of trigeminal ganglia (Fig. 24.12). The central processes of trigeminal ganglion cells enter the mid-pons as the trigeminal nerve. In many ways, the central trigeminal system is organized along parallel lines with the spinal somatosensory system.

Figure 24.12 Sensory components of the trigeminal system. (A) Path for discriminative touch. Large diameter afferents from the face innervate second-order neurons in the spinal trigeminal nucleus (pars oralis) and the principal sensory nucleus. Neurons in these nuclei give rise to axons that cross the midline, ascend in the trigeminothalamic tract, and terminate in the ventral posteromedial (VPM) nucleus of the thalamus. (B) Path for pain and temperature in the trigeminal system. Small diameter afferent axons descend in the spinal trigeminal tract and terminate in the pars caudalis of the spinal nucleus. Second-order axons cross the midline and ascend to the thalamus.

Three nuclei make up the somatosensory part of the trigeminal system. The largest of these is the principal or main sensory nucleus, the cell bodies of which are in mid-pons, at the level of entry for the trigeminal nerve. Acting much like the dorsal column nuclei, the principal sensory nucleus is innervated by large diameter afferents of the ipsilateral half of the face. Its neurons respond to skin indentation and to vibrotactile stimuli. Most of these neurons send their axons across the midline in the pons, where they join the fibers of the medial lemniscus. The trigemino-thalamic axons ascend in the most medial part of the lemniscus (next to the axons that carry information about the hand) and terminate in the VPM.

The spinal trigeminal nucleus is an elongated nucleus, split into three subnuclei distinguished geographically by reference to the obex. Pars oralis occupies the lower pons and upper medulla to the level of the obex. It gives way to the pars interpolaris at the obex and then to pars caudalis through the lower medulla and into the first two cervical segments of the spinal cord. Borders between these subdivisions are hardly distinct as afferents innervating a restricted part of the face may end across two or all three parts of the spinal trigeminal nucleus. The traditional subdivision of the spinal nucleus into functional units accents the mechanosensory functions of pars oralis, the deep receptor functions of pars interpolaris and the nociceptive and thermoreceptive functions of pars caudalis. In this context, the relay of input from pars caudalis to VPM is viewed as the equivalent of the spinothalamic system for the face. Yet studies of C fibers that innervate tooth pulp find these afferents terminate in a long, continuous sheet from the caudal half of the principal nucleus to the caudal-most aspect of pars caudalis. These data indicate a great deal more intermixing of mechanosensory neurons and nociceptive neurons takes place in the trigeminal system than is seen for the spinal somatosensory system.

Cortical Representation of Touch

Neurons of SI Are the First in the Somatosensory System to Show Clear Signs of Lateral Inhibition

Between the level of the peripheral afferent and the level of the cerebral cortex, the somatosensory system keeps information from individual afferents from coming together. Even though the synaptic means exist to generate lateral inhibition in the dorsal column nuclei and in thalamus, the response of single neurons in those regions appears very much like the response of the axon that drives it best. Neurons in SI, however, display true inhibitory surrounds. For area 3b in monkeys, such surrounds are one-third larger than the central excitatory region and can occupy one or more (but rarely all four) sides of the excitatory center. Many neurons in area 3b also exhibit a strong temporal component to their response. Spatial inhibition maintains the response selectivity of neurons when objects scanned across the skin surface at different speeds (as in reading Braille); receptive fields of neurons in area 3b are velocity insensitive. Temporal inhibition performs a parallel function by producing a progressive increase in response rate to surface elements that are scanned more quickly. The lag between the initial excitatory response and the delayed inhibitory one liberates more activity when the velocity of scanning increases. This more than makes up for the reduction in contact time between peripheral receptor and surface feature that accompanies any increase in scanning velocity.

Orientation Selectivity

As a result of circuits in cerebral cortex, the roughly circular receptive fields that enter SI by way of thalamocortical axons become orientation-selective responses in 70% of cortical neurons. The synaptic mechanism for generating a receptive field tuned to the orientation of a stimulus could be convergence of excitatory inputs, much like the mechanism proposed originally for orientation tuning in visual cortex. Yet examination of spatial-temporal response of neurons in SI indicates orientation selectivity is best explained by the presence and spatial distribution of inhibitory regions.

Serial Processing in SI

Area 3b is considered an early step in the cortical processing of tactile information. Much of the data supporting that conclusion come from studies that show ablation of area 3b produces a general decline in tactile discrimination behavior whereas ablation in other areas of SI leads to functional loss that is more selective. These deficits include difficulties in discriminating the texture of a surface following ablation of area 1 and deficits in three-dimensional form perception with ablation of area 2. From these data we conclude that areas of SI are organized as a hierarchy. A similar conclusion is seen in physiological properties of SI neurons as receptive fields become larger and their properties become more complex in going from area 3b to one of the more caudal somatosensory areas (Pons et al., 1992). One example is selectivity for the direction of object movement across the skin. Neurons in area 3b show no sign of direction selectivity, but in areas 1 and 2 this property emerges from the cortical circuitry (Luna et al., 2005).

Columnar Organization

Responses of like type are organized as columns in SI. For SI in macaques one obvious place for columnar processing is in the RA and SA responses. Neurons in layer IV of monkey area 3b, directly innervated by thalamocortical axons, show strong specificity for either RA or SA inputs (Sur et al., 1984). Yet superficial to layer IV, almost all neurons display slowly adapting responses. In other words, the response of neurons outside layer IV makes it appear as though rapidly adapting inputs are incorporated into a slowly adapting output. Nevertheless neurons in areas 3b and 1 are clearly involved in the discrimination of vibrotactile stimuli at low frequencies, such as those carried into the CNS by RA afferents (Meissner’s corpuscles). Response of SI neurons in a macaque is tied to the frequency of a stimulus applied to the monkey’s fingertips. And so his ability to discriminate between two stimuli of different frequencies is only as good as an SI’s neuron’s ability to signal that difference.

The Role of SII in Somatic Sensation

Ablation studies reveal three features of SII’s role in somesthesis:

1. Removal of all SII leaves a macaque incapable of discriminating the shape and texture of a tactile stimuli. These data show any or all subdivisions of SII play a pivotal role in tactile behavior.

2. Removal of SII has no effect on the response of neurons in SI. So, even though SII provides feedback projections to SI, the dominant input to SI comes from neurons of VPL and VPM.

3. Removal or cooling of SI eliminates the tactile responses in SII.

These results extend to modality-specific loss in SII following ablations restricted to one area in SI (removal of area 1 disrupts response to stimulus texture in SII). These observations place SII at a higher level on a series of steps that leads from SI into the medial temporal lobe, where access to memory is achieved

Several Body Representations in SII

At first glance, the division of labor that is a hallmark of SI—its division into four areas—contrasts strongly with the presence of a single area called SII. Recent functional and anatomical studies show, however, that the region in the upper bank of the lateral fissure that normally defines SII in macaques is divided into multiple functionally distinct areas (Fitzgerald et al., 2006). In monkeys three separate regions have been described, referred to as SIIa, SIIc, and SIIp (some researchers prefer the terms SII, PV, and PR; Krubitzer et al., 1995). Anatomical studies in humans suggest there are also four separate regions called OP1–OP4, yet how the human studies relate to the monkey studies is not known. So a modern view of SII indicates it is a complex of at least three functionally distinct areas. The anterior and posterior portions (SIIa and SIIp) are involved in integrating proprioceptive inputs with cutaneous input as a means for representing the size and shape of objects held in the hand. In addition, a central field (SIIc) responds to cutaneous inputs and is important for processing information about 2D shape and texture discrimination.

SII Receptive Fields

Receptive field properties of neurons in macaque SII support the conclusions that SII is part of a serial processing scheme. Neurons in SII are selective for more complex features of a stimulus than are neurons in SI. Moreover, orientation selectivity is seen in fewer than one out of three neurons in SII as receptive fields of single neurons grow to encompass two or more fingers. Neurons such as these appear to represent a sparse code for objects such as the edge of a keyboard or large curved shapes that span several digits.

SII and Attention

Psychophysical studies show that attention is a spotlight that can move freely across somatosensory functions: it has finite boundaries and improves performance on many tactile discrimination tasks. Single unit studies show SII to be one of the major targets of attention as the response of individual neurons changes with shifts in attention. Mechanisms by which attention appears to exert its effects include a change in the response rate—90% of SII neurons in macaques increase their response to a tactile stimulus when the animal attends to the stimulus—and a shift across a population of neurons so that they become active at the same time. Pairs of neurons in macaque SII become more synchronous in their response to a tactile stimulus when an animal pays attention to that stimulus. As the task becomes more difficult, when the difference between two stimuli is deliberately reduced, the degree of synchrony increases by a factor of four. These data show that not only is SII a nodal point for the discrimination of form and texture, but it is also a site at which cognitive mechanisms like selective attention are likely to exert their greatest influence.

At a more global level, SII can be viewed as a gateway through which somatosensory information reaches the medial temporal lobe. There, ongoing events along the skin surface are deposited into long-term memory and compared with previous events stored in memory. This temporal path in somatic sensation underlies object identification—the kind of processing that permits us to pull out from our pockets the right set of keys as we approach our front doors in the middle of the night. The next logical act, inserting the right key into the right lock, demands sensory guidance of movement, and that is the role of the output from SI to posterior parietal lobe. Proprioceptive inputs guide our arms and hands to the correct configuration (the height of the arm, the angle of the hand and the extension of the fingers), while central processing of cutaneous mechanoreceptors, particularly Pacinians, informs us whether the key has struck the side of the lock or moved smoothly into it. That sort of sequence of object recognition and guidance of movement repeats itself dozens, perhaps hundreds, of times a day for all of us, in each case operating efficiently and seamlessly thanks to the central processing of a complex sensory input.

References

1. Braz JM, Nassar MA, Wood JN, Basbaum AI. Parallel “pain” pathways arise from subpopulations of primary afferent nociceptor. Neuron. 2005;47:787–793.

2. Craig AD, Dostrovsky JO. Medulla to thalamus. In: Wall PD, Melzack R, eds. Textbook of Pain. 4th ed., Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone; 1999:183–214.

3. Fitzgerald PJ, Lane JW, Thakur PH, Hsiao SS. Receptive field (RF) properties of the macaque second somatosensory cortex: RF shape, size and somatotopic organization. Journal of Neuroscience. 2006;26:6485–6495.

4. Friedman RM, Khalsa PS, Greenquist KW, LaMotte RH. Neural coding of the location and direction of moving object by a spatially distributed population of mechanoreceptors. Journal of Neuroscience. 2002;22:9556–9666.

5. Iggo A, Muir AR. The structure and function of a slowly adapting touch corpuscle in hairy skin. Journal of Physiology London. 1969;200:763–796.

6. Johnson KO. Neural basis for haptic perception. In: Pashler H, Yantis S, eds. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Wiley; 2001:537–583. Stevens handbook of experimental psychology. Vol. 1 Sensation and Perception.