Chapter 34

Central Control of Autonomic Functions

Organization of the Autonomic Nervous System

The autonomic nervous system (ANS) consists of the neural circuitry that controls the body’s physiology. This network is a morphologically, embryologically, functionally, and pharmacologically distinct division of the nervous system. Working in concert with neuroendocrine mechanisms, the ANS is responsible for homeostasis, or what Walter B. Cannon (1939) referred to as the “wisdom of the body.”

Unlike the skeletal motor system, which innervates striated muscles, the autonomic nervous system innervates the body’s smooth muscle organs and tissues. The ANS projects to, and forms plexuses within, the hollow organs, or viscera, such as the heart and lungs in the thorax and the gastrointestinal, genital, and urinary tracts in the abdomen. It also projects to the blood vessels, glands, and other target tissues found within trunk muscles, limb muscles, and skin.

The ANS also coordinates the body’s physiology to support behavior. In tandem with endocrine controls, the ANS orchestrates the continuous adjustments in blood chemistry, respiration, circulation, digestion, reproductive status, thermoregulation, and immune responses that protect the integrity of the internal milieu, while enabling the functioning and coordination of skeletal muscles and exteroceptive senses into what we know as behavior. Autonomic adjustments are often phasic responses that occur with latencies typical of neural reflexes; in contrast, endocrine responses usually occur more slowly, taking anywhere from minutes to hours to seasons for full expression.

Autonomic impairments lead to the loss of ability to mobilize physiological responses to counter challenges to homeostasis. For example, Cannon (1939), in his landmark experiments, found that destruction of different autonomic pathways devastated the ability of an animal to regulate body temperature, to respond to perturbations of fluid and electrolyte balance, to control blood sugar homeostasis, or to mobilize in response to threats.

A familiar experience illustrates autonomic operations: occasionally, when you have been lying down resting and then jump up suddenly, you may feel dizzy, your vision may become blurred, and you may momentarily have trouble maintaining your balance—let alone doing something active and coordinated. This phenomenon is postural, or orthostatic, hypotension and is caused by insufficient oxygenated blood reaching your brain under the altered hemodynamic conditions produced by the rapid change in posture. Most people experience postural hypotension only occasionally, though for some it is a chronic medical problem. Indeed, it is a debilitating condition in people with various forms of dysautonomia (Bannister, 1989).

A principle underscored by postural hypotension is that behaviors, indeed even simple movements such as a change in posture, require near-instantaneous redistributions of blood flow throughout the body to protect the privileged supply of blood, and thus oxygen and glucose, to the brain. The demands of postural adjustments require unceasing monitoring and rebalancing of circulatory loads. The fact that these adjustments happen continuously and automatically is testimony to the efficiency of the ANS in producing homeostatic adjustments. This example also illustrates two other characteristics of many autonomic responses: often the responses either are initiated in anticipation of the perturbation or implemented so rapidly that the individual does not experience a deficit, and the activity of the ANS is coordinated with activity of the somatic nervous system.

The scope of autonomic functions is hard to overemphasize. Though many early experiments concentrated on autonomic emergency responses, ANS operations are by no means limited to cardiovascular and metabolic adjustments, to “fight-or-flight” situations, or to short-term responses. The ANS has equally essential roles, for example, in all reproductive behavior and physiology, including the choreographies of copulation, gestation, parturition, and lactation. Autonomic reflexes control, on a continuous basis, all bodily interfaces with the environment (e.g., the dermal, respiratory, and digestive epithelia). By its rapid and unceasing adjustments of pupillary diameter and lens accommodation, the ANS facilitates optimal vision. And the ANS plays critical roles in immune system responses; it also coordinates the elimination of metabolic waste products.

The autonomous nature of ANS function is another characteristic of autonomic control. We are rarely aware of ongoing reflex adjustments made to maintain cardiovascular and regulatory dynamics, fluid and electrolyte homeostasis, energy balance, immune system operations, or reproductive functions. Like the batch files of a computer, which execute without normally intruding on the screen or requiring management, autonomic reflex adjustments run unceasingly in the “background.” This makes it practical for other sensory events and functional decisions to occupy the “foreground.” In one of his delightful and trenchant essays, Lewis Thomas (1974) speculates on how disastrous and overwhelmingly confusing it would be if he were put in charge of his liver—if he had to consider all visceral inputs and make a conscious decision for all adjustments in liver function. The ANS takes care of such hepatic, as well as all other visceral, decisions automatically, allowing the individual to focus on the behavioral and cognitive functions that typically require awareness.

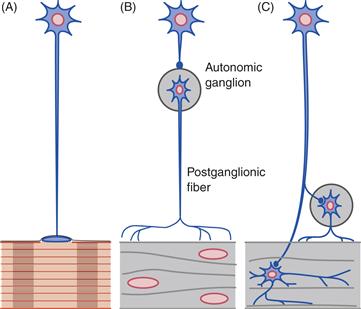

The hub of the autonomic nervous system is the visceral motor outflow, which is divided into sympathetic (SNS) and parasympathetic (PSNS) divisions. Each division is organized hierarchically into pre- and postganglionic levels (Fig. 34.1). The cell bodies of the preganglionic neurons lie within the central nervous system, specifically in the brainstem and spinal cord. Descending projections from more rostral levels of the neuroaxis converge on these ANS preganglionic motor neurons in a pattern similar to that of the centrifugal projections to somatic motor neurons of the brainstem and spinal cord. However, unlike the outflow pattern of the skeletal motor system, in which neurons of the ventral horn or the cranial nerve nuclei project directly to the effector or muscle target, autonomic preganglionic neurons project to peripheral ganglia located between the last CNS station and the target tissues. These ganglia of the ANS contain the postganglionic motor neurons that project to the effector tissues. The extra synapse interrupting the autonomic outflows at peripheral ganglia allows for more divergence, and it also provides opportunities for more local integrative circuitry to impinge on the outflow. Different locations both of the preganglionic motor neurons in the CNS and of the ganglia containing the somata of the postganglionic motor neurons in the periphery are distinguishing features of the two principal divisions of the autonomic nervous system (Langley, 1921; Table 34.1).

Figure 34.1 Somatic and autonomic styles of motor innervation are different. In the somatic motor pattern (A), motor neurons of the spinal cord and cranial nerve nuclei project directly to striated muscles to form neuromuscular junctions. In the autonomic or visceral pattern (B and C), in contrast, motor neurons in the central nervous system project to peripheral postganglionic neurons that in turn innervate smooth muscles. (B) The SNS has preganglionic neurons in the thoracic and lumbar spinal cord (intermediolateral cell column) that project to postganglionic motor neurons in para- and prevertebral autonomic ganglia. (C) The PSNS consists of preganglionic neurons in brainstem cranial nerve nuclei and in the sacral spinal cord (intermediomedial cell column) that project to postganglionic motor neurons in ganglia located near or inside the viscera.

From Nauta and Feirtag (1986).

Table 34.1 Classical Comparisons of Sympathetic and Parasympathetic Divisions of the ANSa

| Characteristic | SNS | PNS |

| Location of Preganglionic Somata | Thoracolumbar Cord | Brainstem; Sacral Cord |

| Location of Ganglia (and thus Postganglionic Somata) | Distant from Target Tissues | Near or in Target Tissues |

| Postganglionic Transmitter | Norepinepherine | Acetylcholine |

| Length of Preganglionic Axon | Relatively Short | Relatively Long |

| Length of Postganglionic Axon | Relatively Long | Relatively Short |

| Divergence of Preganglionic Projections | One-to-Many | One-to-Few |

| Functions | Catabolic | Anabolic |

| Innervates Trunk and Limbs, in addition to Viscera | Yes | No |

aLangley (1921), in splitting the ANS motor outflow into the now-accepted divisions, stressed the contrasting and distinguishing traits of the sympathetic (SNS) and parasympathetic (PSNS) divisions of the ANS. Since his time, most discussions have identified several contrasting features. Most of these distinctions apply generally, but not universally. Although many of these distinctions have blurred (e.g., transmitter) or may be completely unfounded (e.g., divergence), they are often discussed.

Sympathetic Division: Organized to Mobilize the Body for Activity

Sympathetic Responses Coordinate Energy Expenditure, Catabolic Functions, and Adjustments for Intense Activity

“Fight or flight,” Cannon’s prototypical example, epitomizes the operation of the sympathetic division of the ANS. Say you are walking alone at night in an unfamiliar part of town. Although the area is somewhat unsafe and it is too dark to see much of your surroundings, the night is quiet, and you manage to relax. After you walk for several minutes, however, there is a sudden, loud, and unfamiliar noise close by and behind you. In literally the time of a heartbeat or two, your physiology moves into high gear. Your heart races; your blood pressure rises. Blood vessels in your skeletal muscles dilate, increasing the flow of oxygen and energy. At the same time, blood vessels in your gastrointestinal tract and skin constrict, making more blood available to be shunted to skeletal muscle. Digestion is inhibited; release of glucose from the liver is facilitated. Your pupils dilate, improving vision. You begin to sweat, a response serving several functions, including promoting additional dissipation of heat so muscles can work efficiently. Multiple other smooth and cardiac muscle adjustments occur automatically, and almost all of them are affected by the sympathetic division of the ANS.

This fight-or-flight example illustrates important features of the ANS generally and its SNS division more particularly. First, the situation points out the utility of the housekeeping functions of the ANS. If the alarming noise turns out to be a threat and it is necessary to fight or flee, skeletal muscles must be optimally tuned and provisioned. Extra quantities of oxygen and energy are essential. Second, the synergy of adjustments indicates a coordinated and adaptive program of responses, which in this case happen immediately, almost before cognitive evaluation. Third, the short latency of the response is characteristic. Some of the physiological adjustments could be accomplished by hormonal mechanisms, but such adjustments would be too slow to be of much immediate help.

Though the flight-or-fight scenario highlights short-latency responses, not all sympathetic (or parasympathetic) responses happen on such short time scales. ANS operations also involve continuous, ongoing adjustments. Textbook accounts of the emergency functions of the ANS and of single, isolated reflex adjustments sometimes leave the incorrect impression that the ANS is quiescent in the absence of a threat or specific stimulus. Instead, the autonomic nervous system, like the somatic nervous system, always maintains an operating tone. Even during rest, the system maintains appropriate homeostatic balances and autonomic programs.

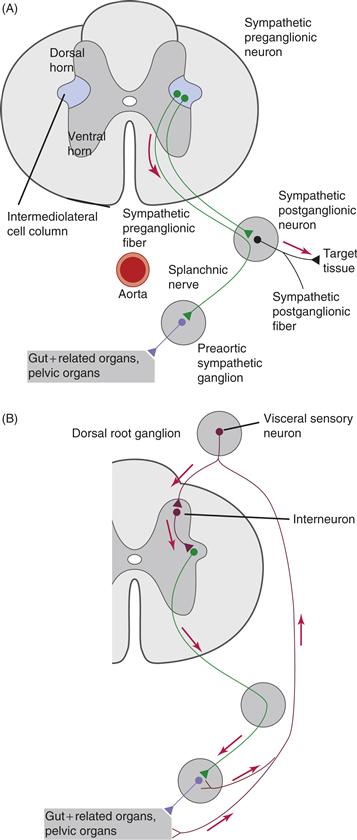

Preganglionic Neurons of the Sympathetic Nervous System Are Located in the Thoracic and Lumbar Spinal Cord

Sympathetic preganglionic neurons occupy the intermediolateral nucleus, a columnar grouping of cells running longitudinally, in the lateral horn of the spinal gray (Strack, Sawyer, Marubio, & Loewy, 1988). In humans, these cells are found between the first thoracic spinal segment (T1) and the third lumbar segment (L3) (Fig. 34.2A). The location of these preganglionic neurons and their axonal outflow gives the SNS another of its names: the thoracolumbar division. Cells within the intermediolateral column are aggregated segmentally. There is a rostral-to-caudal viscerotopic organization to the distribution (Fig. 34.2A). The column is distributed bilaterally, and preganglionics on one side send their axons out the ipsilateral ventral root. The axon of a preganglionic neuron typically exits from the segment in which its soma is located. Many of the preganglionic axons are lightly myelinated, and, as they separate from the ventral root to project to the appropriate peripheral ganglion, they form a white ramus, a connective that takes its descriptive name from myelinated fibers.

Figure 34.2 Details of the organization of the SNS and its sensory inputs. In thoracic and lumbar levels of the spinal cord, preganglionic neuronal somata located in the intermediolateral cell column project through ventral roots to either paravertebral chain ganglia or prevertebral ganglia, as illustrated for the splanchnic nerve (A). Visceral sensory neurons located in the dorsal root ganglia transmit information from innervated visceral organs to interneurons in the spinal cord to complete autonomic reflex arcs at the spinal level (B).

From Loewy and Spyer (1990).

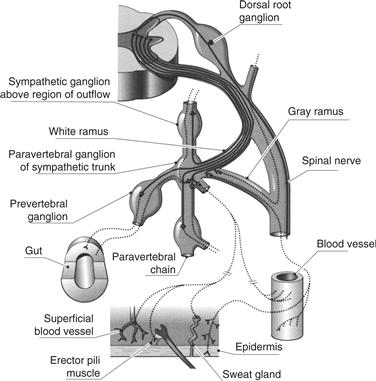

Sympathetic postganglionic neurons are found in two distinct types of peripheral ganglia: paravertebral and prevertebral. Paravertebral ganglia, as the name implies, are adjacent to the spinal cord bilaterally, in a position slightly ventral and lateral to the vertebral column (Figs. 34.3 and 34.4). Each ganglion receives a white ramus from the appropriate ventral root. These ganglia also are interconnected longitudinally into a sympathetic paravertebral chain linked by axons from the preganglionic neurons that run rostrally or caudally to neighboring ganglia of the chain. Axons of the postganglionic neurons of the paravertebral ganglia course centrifugally out of the ganglion to join the peripheral nerves that will carry the individual fibers to their targets. Because most postganglionic axons in the sympathetic nervous system are unmyelinated, these connectives joining the ventral roots are called grey rami.

Figure 34.3 The SNS is organized segmentally. As illustrated here for one segment of the thoracic spinal cord, preganglionic axons exit through the ventral root of the segment in which the preganglionic cell body is located. These preganglionic axons can be myelinated or unmyelinated and can project to the paravertebral ganglion associated with the segment, to neighboring ganglia of the paravertebral chain, to postganglionic neurons located distally in the prevertebral ganglia, or through one of the autonomic nerves.

From Brading (1999).

Figure 34.4 Summary of the major SNS ganglia and their target organs or tissues. Spinal cord is illustrated on the left.

From Loewy and Spyer (1990).

Paravertebral ganglia of the sympathetic chain supply the postganglionic innervation of the head, thorax, trunk, and limbs. For the trunk and limbs, postganglionic axons course both alongside and within the somatic peripheral nerve innervating the region. These autonomic fibers innervate the blood vessels in the muscles (vasoconstrictor fibers), as well as different targets within the skin, including the sweat glands (sudomotor fibers) and erector pili muscles of erectile hairs (pilomotor fibers).

At the rostral end of the sympathetic chain, individual segmental ganglia are fused into aggregate ganglionic groupings. The sympathetic chain, in a modification of the paravertebral chain pattern (Figs. 34.4 and 34.6), innervates the head and the thoracic viscera. The most rostral group, the superior cervical ganglion (supplied from the first and second thoracic segments), supplies the head and neck. The targets of its projections are extensive, including the eyes, salivary glands, lacrimal glands, blood vessels of the cranial muscles, and even the blood vessels of the brain. The paravertebral ganglia just caudal to the superior cervical ganglion form the middle cervical ganglion and, moving caudally, the stellate ganglion. These latter ganglia supply the postganglionic sympathetic outflows that innervate the heart, lungs, and bronchi.

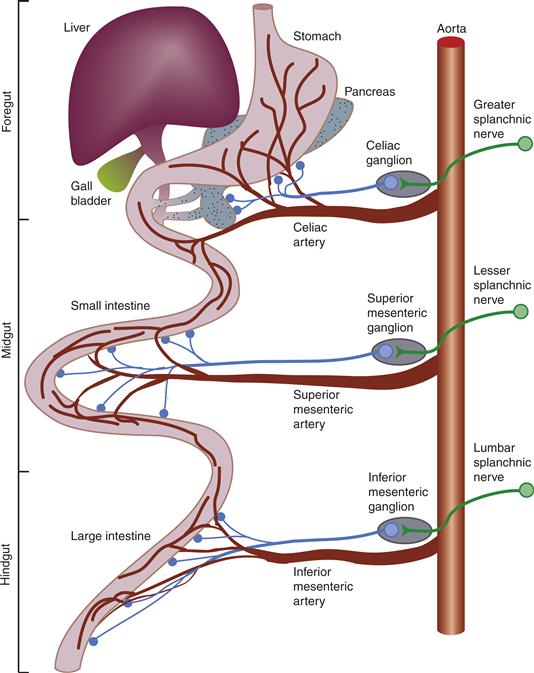

Figure 34.5 SNS innervation of the gastrointestinal tract. This more detailed schematic (compared to Fig. 35.4) illustrates how separate segmental levels of the spinal cord and the associated prevertebral ganglia innervate targets in a topographic, specifically viscerotopic, pattern. The association of autonomic pathways and vasculature is also shown.

From Loewy and Spyer (1990).

Figure 34.6 Autonomic innervation of the head by both sympathetic (superior cervical ganglion) and parasympathetic (cranial nerve nuclei in the medulla and midbrain projecting to the several prevertebral ganglia) pathways. Visceral afferents associated with the autonomic nervous system are found in the trigeminal nerve (cranial nerve V) ganglion.

From Loewy and Spyer (1990).

Unlike the trunk, limbs, head, heart, and lungs, organs of the abdominal cavity are innervated by postganglionic neurons in ganglia situated distal to both the spinal cord and the paravertebral sympathetic chain in locations closer to the target tissue. These sites give the ganglia their distinguishing name: prevertebral ganglia. The preganglionic neurons innervating these sets of postganglionic neurons are located in the intermediolateral column of the spinal cord, like those innervating the paravertebral chain, but their axons pass through the white rami, the chain ganglia, and the gray rami without synapsing. They then make contact with the peripherally situated prevertebral ganglion cells (Fig. 34.3).

There are four major prevertebral postganglionic stations. The more rostral three are located at points where major abdominal arteries separate from the descending aorta, and the ganglia take their names from their associated arteries (Fig. 34.5). Moving from more rostral to caudal, the celiac, superior mesenteric, and inferior mesenteric ganglia innervate the gastrointestinal tract. The celiac ganglion (also commonly called the solar plexus because its connectives radiate from it) projects predominantly to the stomach and rostral-most parts of the foregut and its embryological derivatives, such as the liver and pancreas. Consistent with their progressively more caudal locations, the middle and inferior mesenteric ganglia innervate the mid- and hindgut tissues, respectively. The inferior mesenteric ganglion also supplies the postganglionic innervation to the pelvic organs. The fourth, and most caudal, prevertebral ganglion is the pelvic–hypogastric plexus, which innervates urinary and genital tissues. Perhaps because these prevertebral ganglia are located farther from the spinal cord and closer to the target organs (than the paravertebral ganglia) and because they coordinate responses of visceral organs containing separate nerve networks (the enteric nervous system is described later), these prevertebral ganglia may have more complex neural organization than the paravertebral chain ganglia.

The adrenal medulla is a unique variant of the sympathetic postganglionic pattern. By several criteria, the adrenal medulla is a sympathetic prevertebral ganglion containing postganglionics. However, neurons of this medullary ganglion, rather than issuing axons to innervate target organs, function as a neuroendocrine organ. The adrenal medulla secretes the classical postganglionic sympathetic transmitter norepinephrine, as well as epinephrine, directly into the bloodstream. These catecholamines then circulate as hormones. Release of catecholamines from the adrenals during sympathetic activation provides powerful reinforcement and modulation of the more focal release of catecholamines at traditional—and local—effector sites.

Summary

Overall, the two major motor outflows, or divisions, of the ANS are responsible for the maintenance of homeostasis and support of behavioral responses, but the sympathetic nervous system is the branch specialized for the mobilization of energy. The SNS provides the vascular, glandular, metabolic, and other physiological adjustments that optimize behavioral responses, particularly in emergency situations and conditions requiring activity. The SNS efferent outflow consists of preganglionic neurons, which are located in the intermediolateral column of the thoracic and lumbar spinal cord. SNS efferent axons course to paravertebral and prevertebral ganglia containing the postganglionic neurons, the axons of these postganglionic neurons project to the target tissues.

Parasympathetic Division: Organized for Energy Conservation

Parasympathetic Nervous System Functions Reduce Energy Expenditure and Increase Energy Stores

Functionally, the parasympathetic nervous system mobilizes homeostatic adjustments that are often opposite and reciprocal to those activated by the SNS (see Table 34.1). In particular, PSNS adjustments usually are considered “rest and digest” responses, in contrast to the “fight-or-flight” sympathetic activation. The PSNS promotes anabolic processing, whereas the sympathetic nervous system augments catabolic activity. The PSNS promotes the gastrointestinal processes required to digest and absorb nutrients effectively. This branch of the ANS also augments the efficient use of energy and the storage of extra calories as fat and glycogen. The PSNS, particularly the vagus nerve, plays a central role in controlling the flow of body reserves or energy between storage depots and the tissues that use the energy. The body’s energy reserves are fat in adipose tissue and glycogen in liver and muscle. After a meal, the gastrointestinal tract serves as an additional reservoir of potential energy for the body. By mobilizing triglycerides from adipose tissue or glycogen from liver and muscle, the ANS can make reserves available for metabolism; similarly, by moving nutrient stores (e.g., from the stomach) and promoting their digestion and absorption from the intestines into the bloodstream, the ANS supplies energy to fuel metabolism or to restock triglyceride and glycogen stores, as needed.

Preganglionic Neurons of the Parasympathetic Nervous System Are Located in the Brainstem and the Sacral Spinal Cord

One of the features distinguishing the PSNS from the SNS is the location of their respective preganglionic neurons. PSNS preganglionic neurons are located in two longitudinal columns of neurons: one in the brainstem and the other in the sacral spinal cord. These locations of PSNS preganglionic neurons are responsible for the alternative name of this division of the ANS: the craniosacral (or bulbosacral) division. The longitudinal column of motor neurons in the brainstem is the general visceral cell column, which condenses into a number of nuclei ventrolateral to the cerebral aqueduct system within the brain. These nuclei then project through cranial nerves to targets in the head (cranial nerves III, VII, and IX) or thorax and abdomen (cranial nerve X) (Fig. 34.6). Cranial nerve III, the oculomotor nerve, carries the axons of the accessory, or autonomic, nucleus of the Edinger–Westphal complex, which participate in the control of the pupillary sphincter and ciliary muscles. Cranial nerve VII, the facial nerve, carries preganglionic axons of the superior salivatory nucleus and controls the submaxillary and sublingual salivary glands, as well as the lacrimal glands. Cranial nerve IX, the glossopharyngeal nerve, carries axons of the inferior salivatory nucleus, which control the parotid salivary glands and mucus secretion.

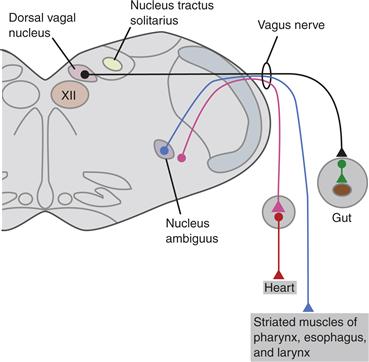

Preganglionic motor neurons of the Xth cranial nerve, the vagus nerve, control smooth muscles and glands throughout the digestive tract, from the pharynx to the distal colon, including viscera such as the liver and pancreas. These Xth nerve neurons occupy the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus, a long fusiform nucleus in the medulla oblongata (Fig. 34.7). They control numerous motor and secretomotor responses that participate in the ingestion and digestion of food, as well as in the assimilation of the nutrients. The vagus nerve also carries motor fibers of a special visceral nucleus, the nucleus ambiguus or ventral vagal nucleus, which controls the striated muscles of the pharynx, larynx, and esophagus and the cardiac muscle of the heart. Much like the case described for sympathetic neurons, motor neurons of the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus and the nucleus ambiguus are organized into viscerotopic subnuclei (e.g., Bieger & Hopkins, 1987; Fox & Powley, 1992).

Figure 34.7 Parasympathetic projections of the vagal motor pathways, the most extensive of the PSNS circuits, to the viscera of the thorax and abdomen.

From Loewy and Spyer (1990).

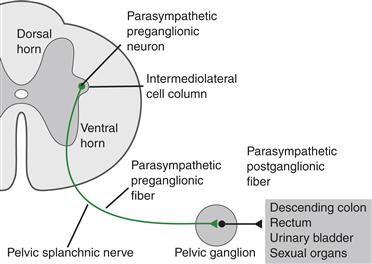

The central representation of the more caudal part of the PSNS is found in the sacral spinal cord, in humans the second (S2) through fourth (S4) sacral segments (Fig. 34.8). The parasympathetic preganglionic somata occupy two longitudinal groupings: one column immediately dorsolateral to the central canal and the other in the same transverse location as that of the intermediolateral column of cells, which sympathetic preganglionics occupy in the thoracic and lumbar cord. Axons of the sacral preganglionics exit the cord in the ventral roots, run in a sacral plexus, and project to the target organs. The sacral preganglionic cell columns control parasympathetic motor, vasomotor, and secretomotor functions of the kidneys, bladder, transverse and distal colon, and reproductive organs.

Figure 34.8 Spinal cord organization of the sacral division of the craniosacral, or parasympathetic, nervous system.

From Loewy and Spyer (1990).

The locations of their respective postganglionic neurons constitute another feature that distinguishes the PSNS from the SNS. Ganglia containing the PSNS postganglionic neurons are juxtaposed to, on the surface of, or even in, the target organ, in contrast to the para- and prevertebral locations of the SNS (Fig. 34.1c). These juxta- and intramural stations often are called plexuses, rather than ganglia. Like SNS prevertebral ganglia, the PSNS postganglionic plexuses are complex integrative sites that typically receive inputs not only from preganglionic neurons, but also from afferents within the plexuses or target tissues. Because the PSNS postganglionic neurons are situated so near their targets, the parasympathetic division of the ANS has, perforce, longer preganglionic axons and shorter postganglionic fibers than the sympathetic division. The relative lengths of the postganglionic fibers in the two divisions have been taken as an indication that individual axons of the SNS may diverge more extensively and innervate larger projection fields, whereas the PSNS may exhibit less divergence and more localized projections. (For counterarguments, see Wang, Holst, & Powley, 1995).

Summary

The parasympathetic nervous system or craniosacral division (i.e., the second major outflow of the ANS) is organized to digest, assimilate, and conserve energy, as well as promote rest. Its anabolic functions include not only those associated with the metabolism of nutrients, but also numerous protective reflexes, such as those that limit heat loss, reduce energy expenditure, and slow the heart. The PSNS outflow consists of preganglionic neurons located in brainstem cranial nerve nuclei or the autonomic columns of the sacral spinal cord. Their axons project to the postganglionic neurons located in ganglia situated near or in the target organs. Postganglionic neurons, in turn, project to the smooth muscle of the target viscera.

The Enteric Division of the Ans: The Nerve Net Found in the Walls of Visceral Organs

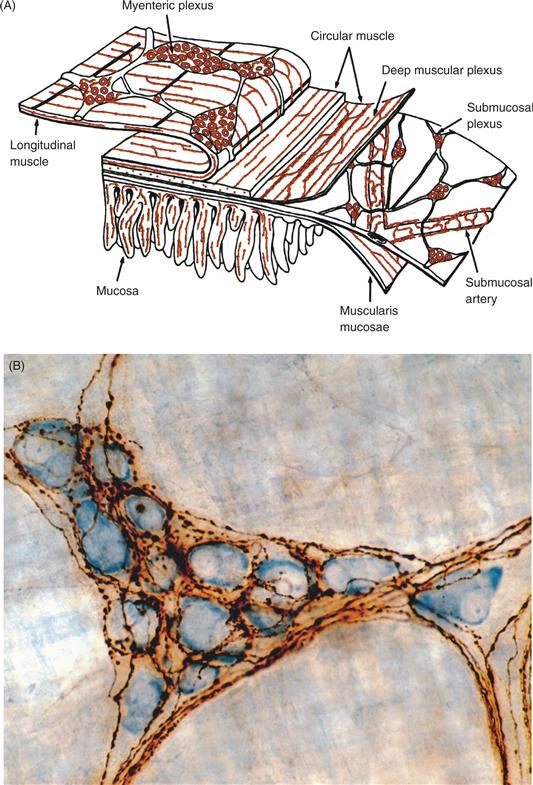

Discussions of the ANS sometimes focus on the SNS and PSNS, but there is a third division as well. When Langley articulated the classic definition of the ANS, he identified the enteric nervous system (ENS) as the third division. The alimentary canal, or “entrum,” and the tissues derived from it, such as those in the pancreas and liver, contain extensive and well-formed neural networks. In particular, the gastrointestinal tract contains two major plexuses that contain as many neurons as the entire spinal cord (Fig. 34.9). Each plexus consists of an extensive sheet of small nodes of cells linked by connectives. One plexus, the myenteric plexus, is situated between outer longitudinal and inner circular muscle layers of the viscus. The other plexus, the submucosal or submucous plexus, is located between the circular muscle layer and the lumenal mucosal layer of the viscera. As illustrated in Figure 34.9, there are additional, less extensive, enteric networks as well.

Figure 34.9 (A) The enteric nervous system plexuses in the wall of the intestine. Enteric neurons form two conspicuous and extensive networks, or plexuses, of ganglia and connectives located between the longitudinal and circular muscle layers of the wall (the myenteric plexus) and the circular muscle layer and the inner mucosal layer (the submucosal plexus). The deep muscular plexus, periglandular plexus, and villous plexus are additional networks of enteric neurons and their processes. From Furness (2006). (B) Autonomic preganglionic terminals innervating postganglionic neurons. This example of vagal preganglionic projections (brown, labeled with the tracer Phaseolus vulgaris) innervating myenteric ganglion neurons (blue, stained with Cuprolinic blue) in the stomach wall illustrates that autonomic preganglionic axons can form extensive networks controlling postganglionics. From Holst, Kelly, and Powley (1997).

The number of neurons in the enteric plexuses, their extensive interconnections, and their capacity to support motility have led to proposals that the enteric nervous system serves as a more or less independent “brain” in the gut (Wood, 1987). Early descriptions emphasized the autonomy of the ENS by observing that the gastrointestinal tract could exhibit movement, peristalsis, even after all extrinsic connections to it were cut. However, fully integrated or coordinated responses of the gastrointestinal tract, including motor responses other than peristalsis, as well as absorptive and secretory responses, involve extrinsic projections from the central nervous system to the enteric nervous system.

Because the preganglionic neurons of the vagus nerve project to the enteric ganglia rather than to independent postganglionic stations, the ENS serves as an extensive postganglionic relay station for the vagus (Fig. 34.9B).

Summary

The ENS or enteric nervous system, the third division of the ANS, consists of ganglia and plexuses of intrinsic neurons in the walls of the viscera such as the gastrointestinal tract. These nerve networks contain intrinsic afferents, interneurons, and efferents that control local functions; they also receive extrinsic inputs from autonomic preganglionic efferents, particularly those PSNS projections coursing in the vagus nerve.

Ans Pharmacology: Transmitter and Receptor Coding

Early in the twentieth century, pharmacological studies performed with naturally occurring agonists and antagonists provided the basis for the original differentiation of two major ANS divisions: the SNS and PSNS. Prior to the pharmacological analyses, the two often had been lumped together. Dale (the contributor of “Dale’s law” of neurotransmitters), Langley, and a number of other early investigators applied natural extracts such as muscarine, nicotine, d-tubocurarine, and others to autonomic ganglia while measuring responses in order to infer the chemical taxonomy of the ANS. Subsequent experiments have replicated the basic distinctions made by these investigators, but this newer research, with access to a pharmacopoeia of synthetic agonists and antagonists, as well as to immunocytochemistry for the characterization of transmitter substances, has described a much richer and more complicated multiplicity of neurotransmitters, neuromodulators, and receptor subtypes in autonomic nerves (Lundberg, 1996).

Preganglionic Neurons Use Acetylcholine as a Transmitter

Most preganglionic neurons of both the SNS and PSNS have a cholinergic transmitter phenotype. Only relatively small subpopulations of preganglionic neurons express other (e.g., dopaminergic or adrenergic) phenotypes. In the peripheral ganglia of these two divisions of the ANS, most postganglionic neurons, which receive inputs from the preganglionics, express a predominance of a nicotinic form of the cholinergic receptor on their somata. As discovered by the early autonomic pharmacologists, nicotine can serve as a general “ganglionic blocker” to thwart transmission at these synapses. Additional specificity and response selectivity, or coding, at the ganglionic level normally are maintained by the segregation of sympathetic and parasympathetic postganglionic neurons in separate ganglia, by point-to-point axonal projections, by distinguishing neuropeptides colocalized with the transmitter, and by the spatial separation of synapses within ganglia.

SNS and PSNS Postganglionic Neurons Use Different Transmitters

The respective transmitter phenotypes of the postganglionic neurons constitute one of the cardinal defining differences between the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system. The majority of SNS postganglionic neurons release the transmitter norepinephrine, whereas PSNS postganglionic neurons release primarily acetylcholine. Such a two-transmitter chemical code produces push–pull or positive bidirectional control of individual targets.

The biomechanics of smooth muscle are quite different from the biomechanics of striated muscle. In contrast to skeletal muscle, smooth muscle is not always organized into antagonistic pairs, with each member of the pair being innervated by a different motor neuron. Also, the smooth (and cardiac) muscles forming the walls of the viscera are not differentially attached to a hard frame to provide mechanical leverage through opposal activity. Reciprocal motor programs of the viscera, for the most part, involve active, phased contraction and relaxation of the same muscle to achieve coordination. To produce these patterns of excitation and inhibition, the target organs and tissues express both adrenergic and cholinergic receptors and have different, often antagonistic or complementary, responses to selective activation of the different receptors.

Response patterns of smooth muscle are further differentiated by specializations of the receptors. Adrenergic receptors, influenced by the catecholaminergic transmitter released by sympathetic fibers, are differentiated into at least four different metabotropic subtypes linked to different intracellular pathways. Similarly, the muscarinic acetylcholine receptor, influenced by the cholinergic transmitter released by parasympathetic postganglionic neurons, is differentiated into at least three ionotropic subtypes with differential influences on intracellular transduction. These heterogeneities of transmitter species and receptor types make it practical to mobilize multiple, different, and potentially highly differentiated responses from one effector tissue (Box 34.1).

Box 34.1 Autonomic Postganglionic Neurons can Change their Transmitter Phenotypes

Transmitter phenotypes of autonomic neurons generally seem fixed, dictated by both intrinsic and extrinsic developmental cues. At least some ANS neurons, however, can alter their phenotypes under appropriate environmental conditions. This conclusion first was reached when populations of postmitotic adrenergic and cholinergic neurons were cocultured in vitro in different media or in the presence of different tissues. Without changes in overall cell number, the percentages of adrenergic and cholinergic neurons in a given culture changed over time. Even more definitively, when single postganglionic cells were grown in microculture wells, the presence of a medium conditioned by heart cells caused some of these mature neurons to change from an adrenergic to a cholinergic phenotype (Potter, Landis, & Furshpan, 1980).

This phenotypic switching does not appear to be an artifact of cell culture situations; the change appears to occur normally in vivo in development to generate the specialized minority of sympathetic postganglionic neurons that are cholinergic (e.g., for innervation of sweat glands). Landis and Keefe (1983) have verified this hypothesis by using rat foot pad sweat gland innervation in vivo and characterizing the transmitter phenotype of the autonomic projections at different stages of development. The developing sympathetic postganglionic innervation of the sweat glands initially expresses a typical adrenergic phenotype as the axon grows toward its target. Once the sweat gland target is innervated, however, the tissue induces the change in neurotransmitter phenotype to a cholinergic one.

Such changes in transmitter are not unique to these examples. Perhaps reflecting pluripotential patterns seen earlier in phylogeny, at least some cholinergic neurons (e.g., avian ciliary ganglion cells) appear to remodel into an adrenergic phenotype, whereas other cells (e.g., maturing neural crest cells in the developing gut wall) exhibit a transient catecholaminergic stage that is lost during the ingrowth of extramural innervation.

Finally, in addition to such switching, autonomic postganglionic neurons also have been shown to exhibit plasticity in altering their levels of transmitters and cotransmitters as a function of the activity of their preganglionic inputs. For example, after preganglionic inputs are blocked or transected pharmacologically, postganglionic neurons of the superior cervical ganglion decrease their levels of tyrosine hydroxylase while increasing their level of substance P.

Terry L. Powley

Response selection may also be facilitated by neuropeptides that the postganglionic neurons synthesize and corelease during activity. Somatostatin, neuropeptide Y, or both are found in many sympathetic neurons; vasoactive intestinal polypeptide and calcitonin gene-related peptide are often coexpressed in parasympathetic neurons. These peptides may serve as neuromodulators that vary postsynaptic responses to the conventional autonomic neurotransmitters (e.g., Costa, Furness, & Llewellyn-Smith, 1987). The release of different neuropeptides and cotransmitters can vary with different rates or patterns of firing and is not invariantly proportional to transmitter release. Thus, a heterogeneity of different cotransmitter and transmitter release patterns can be produced by a single fiber or fiber type, depending on firing pattern and other local factors at the synapse (e.g., Lundberg, 1996).

Although dual innervation in an oppositional or push–pull pattern is presumed to yield faster, more responsive adjustments and to provide a mechanism that can adjust response gain, some tissues are innervated by only one arm of the ANS. The SNS has a wider distribution than the PSNS. In particular, white and brown adipose tissue, peripheral blood vessels, and sweat glands are innervated by the SNS without reciprocal PSNS projections. One possible explanation for this arrangement is that the functions of these particular effectors do not require the speed associated with push–pull projection patterns, particularly in terminating responses once activated. Furthermore, in the evolution of the autonomic nervous system, the SNS is thought to be the older, and correspondingly more extensive, network, whereas the PSNS occurred more recently in phylogeny and therefore has less widespread projections.

Finally, the enteric nervous system also has an extensively varied set of transmitters, cotransmitters, and neuromodulators, providing highly differentiated chemical coding of local functions (Furness, 2006; Lundberg, 1996).

Summary

Both the SNS and the PSNS use acetylcholine as a preganglionic transmitter, but they are distinguished by different postganglionic phenotypes: most SNS postganglionic neurons are catecholaminergic; most PSNS postganglionics are cholinergic. The different neurotransmitter and cotransmitter elements expressed in the postganglionic neurons, as well as numerous postsynaptic receptor subtypes, provide the chemical coding for responses of the PSNS and SNS. This functional organization ensures a varied, powerful, and dynamic push–pull operation of homeostatic systems.

Autonomic Coordination of Homeostasis

The “self-governing” or autonomic characteristic that gives its name to the ANS is based largely on reflexes that involve more than peripheral efferent pathways. Though the early history of autonomic neuroscience emphasized this motor outflow, homeostasis is maintained through the cross-coupling and coordination of multiple reflex arcs. These reflexes involve afferent inputs as well as efferent outputs.

Two major inflows of visceral, or autonomic, afferents (Box 34.2) establish the input arms of the basic reflex arcs. These visceral afferents also provide critical cross-linked feedback between the sympathetic and the parasympathetic outflows, keeping them in balance. For example, sympathetic activity can increase heart rate (tachycardia) and produce constriction of strategic vascular beds, thus leading to an increase in blood pressure. This increase in blood pressure, in turn, is detected by vagus nerve baroreceptors in the aortic arch and other sites. Visceral afferents in the vagus can then reflexively stimulate vagal parasympathetic efferents that slow heart rate (bradycardia). The visceral afferents monitoring the effects of autonomic activity produce positive, reciprocal, and dynamic regulation of physiological responses. When a more sustained adjustment in blood pressure is required (e.g., in the general arousal of the fight-or-flight response), these outflows are adjusted centrally in a process akin to the α–γ linkage so that sympathetic activation is not nullified by parasympathetic responses damping the needed activation.

Box 34.2 Autonomic Reflexes

Activated by Visceral Afferents, Autonomic Afferents, or Just Afferents?

A long-standing dispute about terminology still influences discussions of autonomic reflexes. Some authors (and textbooks) adhere to the original autonomic classification of Langley, who considered the ANS a motor system without a corresponding sensory inflow. This classic view acknowledges that autonomic effectors are influenced by afferents but considers visceral afferents, as well as somatic afferents, as independent of the ANS. Conversely, other scientists (and textbooks) consider afferents arising in and associated with the viscera as the necessary counterpart to autonomic efferents and label them autonomic afferents.

The controversy goes back to Langley’s concentration on a pharmacological definition of the ANS. In his initial studies, Langley speculated about the existence of autonomic afferents, but was unable to find a neurochemical marker to distinguish visceral from somatic afferents. He sidelined the issue pending more information (his seminal book is subtitled Part I), focused his studies on efferents, and never returned to the search for an afferent marker (Part II never appeared). Adherents to his original motor-only classification stress that somatic and visceral afferents can elicit autonomic responses and that both classes of afferents elicit somatic responses, as well.

However, advocates for including visceral afferents within the autonomic schema argue that these afferents innervate the target tissues of the ANS efferents, share similar embryological histories with autonomic efferents, course in the same peripheral nerves as the autonomic efferents (e.g., the vagus), and form mono- and oligosynaptic reflex arcs influencing autonomic preganglionic neurons. These proponents for revision of the autonomic terminology also point out that more recent analyses have identified neuropeptide markers shared by visceral afferents (but not somatic afferents) and autonomic motor neurons. This more inclusive view of the autonomic nervous system seems to be gaining ground. It works more naturally for the discussion of reflexes, and we have adopted it in this text.

Terry L. Powley

Visceral Afferents Link Target Tissues and the CNS

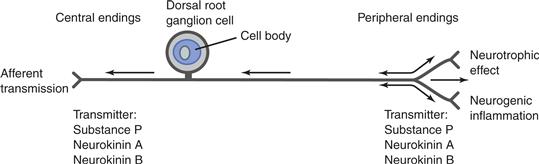

In the case of the sympathetic nervous system, motor neurons receive direct afferent input from most of the autonomic targets. The cell bodies of these primary afferents are located in the dorsal root ganglia of the spinal cord segment(s) in which the corresponding preganglionic neurons are located (Figs. 34.2B and 34.10). Afferent somata are similar to other dorsal root ganglion cells, although they frequently are distinguishable as relatively small, dark neurons or B afferents. From endings in the innervated viscera or tissue, the centripetally directed peripheral processes of the afferents typically course in mixed nerves that also contain the motor outflow. These processes then reach the dorsal roots through the major peripheral nerves. The central processes of these visceral afferents enter the spinal cord in association with Lissauer’s tract, ending in laminae I and V of the dorsal horn (Cervero & Foreman, 1990). For many of these visceral afferents, their endings in the periphery and in the spinal cord contain substance P (SP) and other neuropeptides of the tachykinin family, such as neurokinin A (NKA) and neurokinin B (NKB) (see Lundberg, 1996).

Figure 34.10 Visceral and somatic afferents follow parallel but distinct paths in the central nervous system. Visceral and somatic afferents consist of different populations of dorsal root ganglion neurons that project to laminae I and V of the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. These relay sites provide local spinal reflexes and also project to higher autonomic and somatic sites, respectively, in the brain (A). Although visceral and somatic afferents follow similar trajectories, more detailed analyses indicate the two types of afferents end in distinctly different distributions and densities within the spinal cord (B). IML, intermediolateral cell column.

Visceral afferent nerves relay sensory information about visceral volume, pressure, contents, or nocioceptive stimuli to spinal centers, where automatic responses are interpreted and reflex responses are generated.

In the parasympathetic limb of the ANS, there are two major afferent inflows with different organization. In the cranial division, visceral afferents most often are found in the same cranial nerve as their corresponding motor counterparts. These mixed cranial nerves have sensory ganglia located outside the cranium, and the cell bodies of the afferents are found in these ganglia. Like other visceral afferents, these neurons are typically pseudounipolar neurons with a peripheral neurite extending to the target tissue and a central process projecting to the CNS. The central terminals of these afferents end in a cranial nerve sensory nucleus. Visceral afferents associated with the outflow of cranial nerve III are complex and enter through different channels (e.g., cranial nerve V, the trigeminal nerve). Most of the visceral afferents associated with cranial nerve autonomic reflexes terminate in the extensive nucleus of the solitary tract, which is located immediately dorsal to the general visceral column of the brainstem. Specifically, afferents of VII, IX, and X all end in the nucleus of the solitary tract. These inputs form a viscerotopy in the nucleus, with facial gustatory information projecting most rostrally and medially, the glossopharyngeal information somewhat more caudally, and the afferents of the different branches of the vagus nerve terminating most caudally in different subnuclei of the nucleus of the solitary tract. As the largest and most complex of the visceral afferent relays in the brain, the nucleus of the solitary tract also receives afferent inputs from the spinal division of the trigeminal nerve and second-order inputs from the dorsal column nuclei.

Like visceral afferents associated with the SNS, visceral afferents associated with the PSNS contain SP and other tachykinins. In addition, several neuropeptides found in the gut are also found in some of these afferents. For example, the gut hormone and neuropeptide cholecystokinin (CCK) is found in vagal afferents relaying information from the gastrointestinal tract to the brain. CCK is also found in higher-order ascending relays of vagal projections in the neuraxis, leading some to argue that CCK provides chemical coding for visceral afferents associated with the gastrointestinal tract.

The second major inflow of afferents to the parasympathetic limb of the ANS is associated with the sacral division. Visceral afferents in this division are organized much like the spinal afferents associated with the thoracolumbar or sympathetic division of the ANS (e.g., Morgan, Nadelhaft, & de Groat, 1981).

At the central relays of autonomic reflex arcs, the thoracolumbar spinal circuitry of sympathetic reflexes and the craniosacral circuitry of parasympathetic responses have similar morphological elements. The SNS motor neurons preferentially distribute their dendrites within the long longitudinally oriented column that constitutes the intermediolateral nucleus of the spinal cord. The neurons also distribute a subset of their dendrites dorsolaterally in an arch that brings the dendrites into contact with the incoming visceral afferents (e.g., Dembowsky, Czachurski, & Seller, 1985). Parasympathetic preganglionics exhibit similar dendroarchitecture (e.g., Fox & Powley, 1992). This characteristic dendroarchitecture is consistent with the ideas that local mono- or oligosynaptic reflexes are organized segmentally and at the preganglionic outflows.

Visceral Afferents Also Organize Axon Reflexes and Signal Visceral Pain

In addition to forming conventional reflex circuits throughout the ANS, at least some visceral afferents support effector responses known as axon reflexes. Unlike a conventional reflex, which typically involves an afferent neuron, at least one central nervous system synapse, and an efferent neuron, axon reflexes involve only the afferent neuron and they occur in the target tissue—without a CNS relay. The phenomenon can be seen clearly in the type of experiment that was instrumental in establishing the existence of axon reflexes. If all motor axons projecting to a target tissue are eliminated by surgery or other appropriate means while the afferent innervation of the site is spared, the afferent axons can be stimulated selectively. When the afferent axons are stimulated such that their peripheral processes innervating the target are invaded antidromically, one can measure an effector response or assay the release of a neuropeptide from the peripheral afferent neurite. Such experiments performed on a variety of different visceral and cutaneous afferent systems have demonstrated that axon reflexes produce a number of inflammatory and vascular effector responses (Lundberg, 1996).

When a peripheral ending of a visceral afferent transduces a stimulus, the resulting action potential can release the neuropeptide contained in vesicles in that ending (Fig. 34.11). The released compound then acts as a neuromodulator or neurotransmitter to produce local changes on smooth muscle—a local, or peripheral, axon reflex. The response is also relayed to neighboring tissues. When an action potential is transmitted centrally in an afferent axon, it can also be transmitted centrifugally by collaterals of the same fiber, and release of the neuromodulator from these collateral endings can propagate the reflex in the immediate area. The inflammatory responses and extravasation associated with the classic “wheal and flare” reaction to skin damage were the first axon reflexes analyzed and are a classic illustration of the phenomenon. Such local responses have been widely documented not only in the skin, but also in viscera such as the lungs.

Figure 34.11 The architecture of visceral afferents that produce axon reflexes. Visceral and cutaneous afferents release transmitters from the tachykinin family. When action potentials (indicated by arrows) are generated peripherally, they are propagated centrally. Peripherally generated action potentials also produce a local release of tachykinins in the affected terminals and in terminals of the peripheral collaterals.

Finally, visceral afferents, particularly those associated with SNS pathways, are responsible for visceral pain (Craig, 2002; Jänig, 1996).

Summary

Visceral afferents innervate the target tissues of the ANS, and their axons frequently course in the same peripheral nerves as autonomic efferents. Also commonly called autonomic afferents, these sensory elements associated with the ANS constitute the afferent limbs of autonomic reflexes and carry the inputs recognized as visceral pain. Visceral afferents also mediate axon reflexes and are cross-linked with somatic, as well as autonomic, nervous system activity.

Hierarchically Organized ANS Circuits in the CNS

Homeostasis no more occurs through isolated autonomic reflexes than posture is maintained, or movement is executed, through isolated somatic reflexes. Nevertheless, methodological and historical considerations have yielded a tendency to focus on individual autonomic reflexes. Methodologically, the need for experimental control typically dictates that experiments isolate a reflex (or small set of reflexes) for examination. In addition, historically, the ANS was conceptualized primarily as a motor branch of the peripheral nervous system.

Though the separate-reflex perspective has in some ways shaped a view of ANS functions as a collection of individual motor responses, autonomic activity typically involves finely coordinated, fully integrated adjustments of multiple outflows. Just as somatic posture and movement are coordinated by supraspinal CNS controls, autonomic integration is achieved by supraspinal controls. The preganglionic motor pools of the craniosacral and thoracolumbar outflows are final common paths for descending projections from the CNS. Similarly, the first- and second-order visceral afferent relays (e.g., the nucleus of the solitary tract and the spinal lamina V), which form short, mono-, or oligosynaptic reflex arcs with these preganglionic motor pools, are targets of rostral CNS stations that coordinate and modulate the autonomic outflows.

The CNS coordination of autonomic activity achieves a number of integrative functions:

• Much like the suprasegmental organization of skeletal motor responses, central ANS stations provide coordination and sequencing of different local autonomic reflexes. These stations provide, for example, the efferent choreography necessary to coordinate the sequential autonomic responses in the mouth, stomach, intestines, and pancreas during and after a meal. Such programs coordinate brainstem and spinal cord efferents, as well as reflexes within the SNS and PSNS divisions of the autonomic outflow.

• Central ANS circuitry also cross-links autonomic activity and somatic motor activity. The example used earlier of cardiovascular adjustments occurring in concert with postural adjustments illustrates such linkage between autonomic and somatic nervous system outflows.

• The CNS stations of the autonomic nervous system also provide the information, as well as the organization and planning, that enables an organism to mobilize autonomic adjustments or responses in anticipation of environmental contingencies and developing needs. For example, both fluid and energy homeostasis involve physiological adjustments in anticipation of major imbalances or deficits, responses that cannot be explained solely by reactive reflexes.

The importance and the nature of central autonomic controls are underscored by clinical disorders that result from interruptions in the connections between the central autonomic circuitry and the preganglionic motor neurons (Box 34.3). Quadriplegia and paraplegia, which result from injuries that divide the separate thoracic and lumbar sympathetic loops and sacral parasympathetic pathways from higher central regions, illustrate how essential these longitudinal connections are. Interruption of the longitudinal connections causes loss of voluntary bladder and bowel control. Disruption of the spinal cord also causes men to become impotent because penile tumescence is a predominantly parasympathetic response and ejaculation is a sympathetic response. Although erections can occasionally be elicited as local reflexes caused by direct mechanical stimulation, ejaculations, which normally require suprasegmental coordination, almost universally disappear. In addition, numerous vascular and glandular reflexes are also disordered by the interruption of long autonomic pathways connecting the brain and spinal cord (Bannister, 1989).

Box 34.3 Diseases and Aging Impair the Autonomic Wisdom of the Body

The importance of the autonomic nervous system to health often goes unnoticed. When ANS functions operate normally, they typically occur automatically, without the individual being aware of any adjustments. Nevertheless, loss of an autonomic response can be disruptive, and autonomic disorders can be debilitating (Bannister, 1989). In a classic example of ANS degeneration known as multiple system atrophy and autonomic failure, or the Shy–Drager syndrome, individuals exhibit postural hypotension, urinary and fecal incontinence, sexual impotence, loss of sweating, cranial nerve palsies, and a movement disorder similar to Parkinson’s disease. Disconnection of the suprasegmental autonomic stations from the spinal cord can occur in neurological disorders, such as multiple sclerosis, and traumatic spinal cord injury. As a result, bowel and bladder control are lost, and impotence is caused by a loss of autonomic genital reflexes.

Some autonomic disorders are less conspicuous. In part, the apparently more subtle deficits may be ones that are less important in the carefully controlled environments found in modern societies. For example, impaired thermoregulatory responses may be tolerated well by a person living in a climate-controlled environment. Also, metabolic emergencies are unlikely to occur and need autonomic compensation if a person regularly eats enough food. Nevertheless, autonomic disorders occasion a number of serious, even life-threatening, health problems.

Autonomic imbalances can take many different forms. Excess activation of the ANS is implicated in various stress-related disorders, including ulcers, colitis, high blood pressure, and heart attacks. As discussed earlier, chronic failure of autonomic cardiovascular homeostasis can cause debilitating postural hypotension. Developmental autonomic disorders, such as immature or anomalous medullary respiratory circuitry, are thought to contribute to sudden infant death syndrome. Some sleep disorders, such as sleep apnea, are also thought to have autonomic elements. Furthermore, widespread autonomic dysfunction resulting from autonomic neuropathies of diabetes, alcoholism, and Parkinson’s disease complicates the primary diseases. Autonomic disturbances can also underlie metabolic disorders, such as stress-induced diabetes and reactive hypoglycemia. Autonomic disturbances have also been hypothesized to be a cause of obesity.

Autonomic function is not only impaired by diseases, it is also compromised by aging processes—even those of healthy aging (Amenta, 1993). With aging, both cell losses and neuropathies of surviving neurons occur in ANS circuits. Such age-related changes in the ANS reduce an individual’s ability to optimize and sustain homeostatic responses. These consequences of aging produce both primary autonomic disorders and secondary complications and vulnerabilities when the individual is challenged by disease or injury.

Terry L. Powley

Early Stimulation and Lesion Experiments Identified a Central Component of the ANS

Like the concept of the ANS itself, the corollary that the ANS includes a hierarchy of central mechanisms was first demonstrated by physiological experiments. Nineteenth- and early twentieth-century experiments manipulating the brain caused autonomic disturbances. In one classical experiment, for example, Claude Bernard demonstrated that localized mechanical lesions, or stab wounds, in the floor of the fourth ventricle near the dorsal vagal complex produced a “piqure glycosurique,” a disturbance of blood glucose homeostasis characterized by a diabetes-like condition in which glucose spills into the urine. Subsequent lesion and stimulation studies identified a number of “centers” for micturition, respiration, and other autonomic functions in the medulla oblongata and pons.

Other experiments implicated the hypothalamus in even more extensively coordinated and cross-linked autonomic patterns. This work led to the concept of the hypothalamus as the “head ganglion” of the autonomic nervous system. Following an earlier application of electrical stimulation to the hypothalamus by Karplus and Kreidl, Walter Hess found that focal electrical stimulation of regions of the hypothalamus elicited coordinated patterns of sympathetic and parasympathetic adjustments (e.g., changes in pupil size, piloerection, and respiration) and affective responses that were appropriate to behavioral responses elicited from the same loci. In fact, central manipulations that affect autonomic function seem practically invariably to produce adjustments of both SNS and PSNS outputs, an observation that underscores the integrative role the brain plays in ANS function.

Brain lesions in virtually all limbic system regions, and notably in the septal area, amygdala, hippocampus, frontal cortex, cingulate cortex, and insular cortex, have been shown to exaggerate, dissociate, blunt, or in other ways distort autonomic responses to environmental situations.

Anatomical Mapping Experiments Have Identified Multiple Hierarchically Organized, Reciprocally Interconnected Stations of the Visceral Neuroaxis That Control Autonomic Activity

As neuroscience tracing tools have become more powerful, they have revealed an extensive CNS autonomic control hierarchy coupling visceral afferent inputs with autonomic efferent outflows, linking the SNS and PSNS divisions of the ANS, and interconnecting the central autonomic stations with somatic and endocrine pathways in the brain (Box 34.4). This central autonomic circuitry has been considered a “central visceromotor system” (Nauta, 1972) or a “central autonomic network” (Loewy, 1981). These studies revealed a network of multisynaptic relays descending from the hypothalamus and midbrain to preganglionic neurons in the brainstem and spinal cord. Similar projections, both direct and relayed through the hypothalamus, were also found for a number of limbic system nuclei, including most prominently the amygdala (Nauta, 1972). Neural tracers, immunocytochemical techniques, and electron microscopy subsequently have increased the resolution of the maps of this circuitry and its transmitters (e.g., Loewy, 1981).

Box 34.4 Central ANS Circuits Integrate Autonomic Reflexes with Affective or Emotional Responses

The autonomic nervous system participates in emotion and motivation. Consider Cannon’s prototypical fight-or-flight example: The somatic and autonomic adjustments in this emergency situation contain elements we associate with anger or fear. The central relays, including the limbic circuitry just discussed, organize the autonomic components of these responses to external environmental stimuli and coordinate them with the appropriate somatic responses. Thus, the central ANS circuitry is involved in the expression of emotional reactions. This central circuitry has been called the “emotional motor system.”

Some have hypothesized that in addition to being involved in the expression of emotions, the ANS is also the substrate for the experience of emotions. The classic theory of this type was suggested over a century ago independently by James and Lange, who speculated that afferent experience resulting from autonomic adjustments might be the basis of emotional experiences. For the fight-or-flight example, the James–Lange idea could be considered the proposition that “you do not run because you are afraid; you are afraid because you run (and mobilize the requisite autonomic adjustments registered by your visceral afferents).” Cannon, in the early twentieth century, offered an influential refutation of the James–Lange theory and delayed acceptance of these ideas, but most of his argument was based on now-outmoded ideas about the ANS and on a lack of distinction between expression and experience.

In an experiment designed to examine the James–Lange idea, Hohmann (1962) surveyed army veterans who had sustained spinal cord injuries at different levels. Consistent with a prediction of the theory, Hohmann found that, for the veterans’ self-reported experiences of both fear and anger, the higher their spinal cord lesions (and thus the more of their visceral afferent inflow that was disconnected from the brain), the greater the reduction in their affective experiences.

In recent years, observations with fMRI and other scanning techniques, with modern electrophysiological techniques combined with tracing and with neuropsychological analyses of patients with brain damage or spinal injury, have converged to suggest that emotions or “feelings” are central representations of visceral afferent inputs. In particular, experiments that elicit visceral afferent activity and others that generate experiences judged to be emotions are associated with comparable activation patterns in limbic structures and forebrain sites. Recently, in views compatible with the James-Lange account of emotion, Damasio (1999), Craig (2002), and others as well have suggested that emotional experience is to the autonomic adjustments of the body what proprioception and somatosensation are to skeletal nervous system operations.

Terry L. Powley

The paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus is a prototype of the extensive and profound central autonomic coordination. Parvocellular neurons in the paraventricular nucleus project monosynaptically to preganglionic neurons in the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus and preganglionics in the intermediolateral column of the spinal cord. The paraventricular nucleus also projects to the visceral afferent relay nuclei associated with each of these efferent outflows (the nucleus of the solitary tract and spinal lamina V, respectively). These descending projections influence several cardiovascular and gastrointestinal responses. Illustrating the extent of the central integration of responses, additional neurons of the paraventricular nucleus control corticotropin-releasing factor and oxytocin neuron responses, which often are activated or modulated in association with autonomic functions.

Most mesencephalic, diencephalic, and telencephalic nuclei considered part of the limbic system affect visceral motor outflows and are now included in the concept of the central visceromotor system. In addition to the central gray and paramedian regions of the mesencephalon and the entire hypothalamus, including the preoptic hypothalamus, these limbic sites include the amygdala, bed nucleus of the stria terminalis, septal region, hippocampus, cingulate cortex, orbital frontal cortex, and insular and rhinal cortexes.

Summary

Multiple subcortical and diencephalic structures impose special controls over the SNS and PSNS. This network of hierarchically organized central stations, many of them part of the limbic system, forms a central visceral neuroaxis that receives inputs from visceral afferents and issues descending projections to the ANS preganglionic neurons in the brainstem and spinal cord. This central autonomic circuitry organizes and sequences sets of separate autonomic reflexes, coordinates SNS and PSNS responses so that they are synergistic, cross-links autonomic and skeletal responses, and integrates autonomic activity with ongoing and anticipated behavior of the individual.

Perspective: Future of the Autonomic Nervous System

Our understanding of the autonomic nervous system is incomplete and evolving, driven by the technological advances in neuroscience. Molecular biology, immunocytochemistry, electron microscopy, fMRI and similar imaging protocols, and other modern techniques are changing the autonomic nervous system definition that was derived with the techniques available to Langley and his contemporaries at the beginning of the twentieth century. The distinction that sympathetic postganglionic neurons are noradrenergic whereas parasympathetic postganglionics are cholinergic has been blurred by the recognition of nonadrenergic noncholinergic (NANC) neurons, nitric oxide synthetase (NOS)-containing neurons, purinergic synapses, a large number of colocalized and coreleased neuropeptides, postganglionic neurons changing their neurotransmitter phenotypes, and other exceptions that broaden the view developed by Langley’s pharmacological studies. The canon that the ANS is strictly a motor system without an afferent counterpart is challenged by many who argue on functional and molecular biological grounds that “visceral afferents” belong to the ANS (see Box 34.2).

The proposal that functional differences between the SNS and PSNS divisions of the ANS can be attributed to their contrasting patterns of projection (the sympathetic system preganglionics projecting to postganglionics in a one-to-many pattern; the parasympathetic system projecting in a one-to-few pattern) has not been substantiated by modern analyses of divergence (Wang et al., 1995). Continued application of modern technologies and the prospect of continuing developments promise to define an autonomic nervous system quite different from that envisioned by Langley.

Summary and General Conclusions

The autonomic nervous system is the neural circuitry that maintains homeostasis and health and that enables behavior. It is responsible for the physiological adjustments that achieve what Cannon recognized as the “wisdom of the body.” With its sophisticated motor repertoire and complexes of reflexes, including local axon reflexes, segmental or oligosynaptic reflexes, and polysynaptic suprasegmental cascades, the ANS continuously adjusts and defends the body’s physiology. The importance of these processes was summarized succinctly by Nauta and Feirtag (1986): “Life depends on the innervation of the viscera; in a way all the rest is biological luxury.” The processes go on, for the most part, without awareness or cognitive representations.

The hub of the ANS consists of two separate motor outflows, each hierarchically organized with preganglionic neurons stationed in the CNS and postganglionic neurons located in peripheral ganglia. The sympathetic, or thoracolumbar, division facilitates the mobilization of energy, increases catabolism, and promotes physiological responses that support activity, including emergency responses such as “fight” or “flight.” The parasympathetic, or craniosacral, division facilitates conservation of energy, increases anabolism, and supports physiological responses that typically promote rest, digestion, and restoration of body reserves. The adrenergic phenotype of sympathetic postganglionic neurons, the cholinergic phenotype of parasympathetic neurons, and distinguishing complements of neuropeptides and receptor specializations provide neurochemical coding for the two divisions of the ANS. A key peripheral pole—and third distinct division of the ANS—is the enteric nervous system found in the wall of the digestive tract.

The motor outflows of the ANS are efferent limbs of reflexes triggered by visceral and, in some cases, somatic afferents. These reflex circuits have second-order visceral afferent nuclei located adjacent to spinal and medullary nuclei of preganglionic motor neurons (laminae I and V and the nucleus of the solitary tract, respectively).

Higher-order CNS circuitry, including the hypothalamus, limbic system, and a variety of cortical sites, provides hierarchical control and integration of autonomic reflexes. This hierarchy is responsible for coordinating different autonomic reflexes, integrating autonomic function with somatic activity, and executing response programs that anticipate needs and regulate physiology over more extended time scales than those represented by isolated reflexes.

References

1. Amenta F, ed. Aging of the autonomic nervous system. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 1993.

2. Bannister R. Autonomic failure: A textbook of clinical disorders of the autonomic nervous system 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford Medical Publications; 1989.

3. Bieger D, Hopkins DA. Viscerotopic representation of the upper alimentary tract in the medulla oblongata in the rat: Nucleus ambiguus. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1987;262:546–562.

4. Brading A. The autonomic nervous system and its effectors Oxford: Blackwell Science; 1999.

5. Cannon WB. The wisdom of the body 2nd ed. New York: Norton; 1939.

6. Cervero F, Foreman RD. Sensory innervation of the viscera. In: Loewy AD, Spyer KM, eds. Central regulation of autonomic functions. New York: Oxford University Press; 1990:104–125.

7. Costa M, Furness JB, Llewellyn-Smith IJ. Histochemistry of the enteric nervous system. In: Johnson LR, ed. 2nd ed. New York: Raven Press; 1987:1–40. Physiology of the gastrointestinal tract. Vol. 1.

8. Craig AD. How do you feel? Introception: The sense of the physiological condition of the body. Nature Neuroscience Reviews. 2002;3:655–666.

9. Damasio A. The feeling of what happens: body and emotion in the making of consciousness New York: Harcourt Brace; 1999.

10. Dembowsky K, Czachurski J, Seller H. Morphology of sympathetic preganglionic neurons in the thoracic spinal cord of the cat: An intracellular horseradish peroxidase study. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1985;238:453–465.

11. Fox EA, Powley TL. Morphology of identified preganglionic neurons in the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1992;322:79–98.

12. Furness JB. The enteric nervous system Malden, Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishing; 2006.

13. Hohmann GW. Some affects of spinal cord lesions on experienced emotional feelings. Psychophysiology. 1962;3:143–156.

14. Holst M-C, Kelly JB, Powley TL. Vagal preganglionic projections to the enteric nervous system characterized with PHA-L. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1997;381:81–100.

15. Jänig W. Neurobiology of visceral afferent neurons: Neuroanatomy, functions, organ regulations and sensations. Biological Psychology. 1996;42:29–51.

16. Landis SC, Keefe D. Evidence for transmitter plasticity in vivo: Developmental changes in properties of cholinergic sympathetic neurons. Developmental Biology. 1983;98:349–372.

17. Langley JN. The autonomic nervous system part I Cambridge: Heffer; 1921.

18. Loewy AD. Descending pathways to sympathetic and parasympathetic preganglionic neurons. Journal of the Autonomic Nervous System. 1981;3:265–275.

19. Loewy AD, Spyer KM, eds. Central Regulation of Autonomic Functions. New York: Oxford University Press; 1990.

20. Lundberg J. Pharmacology of cotransmission in the autonomic nervous system: Integrative aspects on amines, neuropeptides, adenosine triphosphate, amino acids and nitric oxide. Pharmacological Reviews. 1996;48:113–178.

21. Morgan C, Nadelhaft I, de Groat WC. The distribution of visceral primary afferents from the pelvic nerve within Lissaure’s tract and the spinal gray matter and its relationship to the sacral parasympathetic nucleus. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1981;201:415–440.

22. Nauta WJH. The central visceromotor system: A general survey. In: Hockman CH, ed. Limbic system mechanisms and autonomic function. Springfield, IL: Thomas; 1972;21–40.

23. Nauta WJH, Feirtag M. Fundamental neuroanatomy New York: Freeman; 1986.

24. Potter DD, Landis SC, Furshpan EJ. Dual function during development of rat sympathetic neurones in culture. The Journal of Experimental Biology. 1980;89:57–71.

25. Strack AM, Sawyer WB, Marubio LM, Loewy AD. Spinal origin of sympathetic preganglionic neurons in the rat. Brain Research. 1988;455:187–191.

26. Thomas L. Autonomy: The lives of a cell New York: Viking Press; 1974; (pp. 64–68).

27. Wang FB, Holst M-C, Powley TL. The ratio of pre- to postganglionic neurons and related issues in the autonomic nervous system. Brain Research Reviews. 1995;21:93–115.

28. Wood JD. Physiology of the enteric nervous system. In: Johnson LR, Christensen J, Jackson MJ, Jacobson ED, Walsh JH, eds. 2nd ed. New York: Raven Press; 1987;67–110. Physiology of the gastrointestinal tract. Vol. 1.

Suggested Readings

1. Handbook of chemical neuroanatomy. Vol. 6. Björklund A, Hökfelt T, Owman C, eds. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science; 1988.

2. Brading A. The autonomic nervous system and its effectors Oxford: Blackwell Science; 1999.

3. Burnstock G. In: Chur, Switzerland: Harwood Academic; 1992–2000; The Autonomic nervous system. Vols. 1–12.

4. Cameron OG. Visceral sensory neuroscience interoception New York: Oxford University Press; 2002.

5. Cannon WB. The Wisdom of the body 2nd ed New York: Norton; 1939.

6. Gabella G. Structure of the autonomic nervous system London: Chapman & Hall; 1976.

7. Hockman CH, ed. Limbic system mechanisms and autonomic function. Springfield, IL: Thomas; 1972.

8. Jänig W. The Integrative action of the autonomic nervous system: Neurobiology of homeostasis Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2006.

9. Ritter S, Ritter RC, Barnes CD, eds. Neuroanatomy and physiology of abdominal vagal afferents. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 1992.