5

Created by Culture

Why are humans so different to other animals? When I ask people this question, they typically list all kinds of very sensible things – language, technology, art, memory, sense of humor, and so on. But underlying this list is an assumption so obvious that people don't even bother to include it – humans are just smarter.

Humans have giant brains that make them more intelligent than other animals. But as you've seen so far, human intelligence and innovation are more complicated than people often assume. Yes, we are smarter, but not for the reasons people often assume and not in the ways people often assume. Hopefully, by now, you have a better sense of how the theory of everyone applies to the human animal – how we think, the cultural nature of our intelligence, the way we learn and learn from one another, and the way we work together to innovate. Almost all aspects of our behavior and the nature of our societies are linked by this theory of everyone. With it, we can begin to understand everything from our capacity for language to the origins of the patriarchy to the existence of grandmothers and more. This will be important when, in Part II, we begin to think about where we need to go next. And it all starts with our giant cultural brains.

The human brain has tripled in size in the last few million years. Our brains are now about three times as large as a chimp's. And, you might think, that makes sense! Bigger brains are better! Who doesn't want a bigger brain? And you're right, bigger brains can store and manage more information. But if you think bigger brains are always better, you should stop and wonder why all species don't have giant brains? What's stopping them?

The answer lies in the law of energy. Brain tissue is energetically expensive, using over twenty times more energy than the same mass of muscle tissue. It's cheaper and easier to evolve brawn than brain. And so that's what most animals do; they get stronger, not smarter.

Larger brains might help you escape predators, outcompete other members of the group, and survive better in an environment, but they can only do that if they can pay their energy bills. Bigger brains have to justify their size by helping you find more food. Most animals, including us for most of our history, spent most of the time sorting out dinner. So really what an animal wants is the smallest brain that lets them get the job done – find food, outcompete other animals, evade predators, and so on. Too large a brain is like driving too big a car. It comes with ongoing fuel costs. And so encephalization – the evolution of big brains – needs an explanation. That explanation will help you understand how seemingly disconnected aspects of ourselves and our society fit together.

Explaining encephalization

We used to think that brains evolved for the Machiavellian manipulation of other group members or simply for keeping track of others in our groups – a social brain hypothesis. But we now know that that's only part of the story. Brains are not simply for tricking or tracking others; instead, they're for what you think they're for: storing, managing, and using information. Yes, for thinking! That information could be social information about other group members, but it doesn't have to be. It could be acquired from others, but it doesn't have to be.

Animals can learn all kinds of adaptive knowledge – where food is, how to evade predators, how to outcompete other individuals to secure a mate. And that knowledge can be learned by yourself through individual exploration and trial and error or by learning from others. Learning from others is by far the most efficient way to learn.

At the extreme, one could learn only the answers from others, like a lazy kid in class peeking at the exam papers of those who've studied; it's easier to copy answers than do the work yourself. Humans are like that cheating child. They arrive in the world, don't really try to figure out how it works, but instead just figure out what the past generation are doing, what most people are doing, and what the most successful members of society are doing. And then, like the Scottish children we met in Chapter 2, we just copy that. Of course, as we learned, it's not quite that simple, but as we're about to see, that general social learning approach also completely changed every aspect of ourselves and our societies. This is the cultural brain hypothesis.

Cultural brain hypothesis

The cultural brain hypothesis (CBH) makes predictions for the interconnected, bidirectional relationships between brain size, group size, innovation, social learning, mating structures, and length of the juvenile period, depending on ecology and reliance on social learning across the animal kingdom. It also has secondary implications for mating strategies and the existence of grandparents that we'll get to in a moment. The theory predicts that among social learning animals, larger brains should be associated with larger groups, more social learning, more adaptive knowledge, more innovation, and longer juvenile periods. Why? Because ultimately brains evolve in lockstep with the information they can access and the calories that information unlocks.

Brains, as mentioned earlier, are for storing, managing, and using information. Bigger brains can store, manage, and use more information. You can acquire that information through some combination of asocial learning – trial-and-error reinforcement learning, building a causal model of understanding, figuring it out on your own – and social learning – copying what other members of your group are doing. But regardless of how you get that information, if you have more information that unlocks more energy, it increases the group's carrying capacity, which is how many individuals the environment can support.

As per the laws of energy and innovation, more information can give you more access to energy. And so with more or better adaptive knowledge, the number of individuals who could in principle survive increases.

Think of how improved knowledge about food production, from the Agricultural Revolution to the Green Revolution, or the astonishing advances in modern medicine, from antibiotics to vaccines, have allowed more of our species to survive regardless of whether they understand the Haber-Bosch process for making fertilizer or how exactly a vaccine works. All that knowledge leads to more people.

But if you're a social learner, those larger groups are also useful to you in another way that we discussed. They give you more individuals from whom you can learn. In other words, a larger collective brain. As a result, brain size and group size are more strongly correlated among social learners, not directly for tricking and tracking but indirectly through the knowledge that groups offer to the social learner and through the knowledge leading to larger groups. Bigger brains, more knowledge, and larger groups are a package, mediated by the amount of adaptive knowledge.

Social learning is an efficient way to learn. Learning from someone else is far more efficient than trying to figure things out on your own. In fact, with enough information in the population, a social learner can actually get away with a smaller brain than an asocial learner. This might seem counterintuitive, but remember, an animal would prefer to have a smaller brain, so if you can get away with a smaller brain because the intelligence of your society helps you survive, then brains shrink as smaller brains outcompete bigger brains. Curiously, this brain shrinkage is actually what we see in humans.

The human brain, after growing for millions of years, has begun shrinking over the last ten thousand years or so. The cultural brain hypothesis predicts that such shrinkage is consistent with increased cultural innovation. Culture and our collective brain allow more people to survive even if individually they're not particularly bright – they can get away with not always coming up with the best answers simply by copying what most other people are doing. For example, we can benefit from a hospital even if we know nothing about medicine.

But this shrinkage only happens when the pressure to learn more isn't high. As the amount of adaptive knowledge that you have to learn grows, if there's more than your brain can handle then this creates a selection pressure for a larger brain. This is what happened for most of human history.

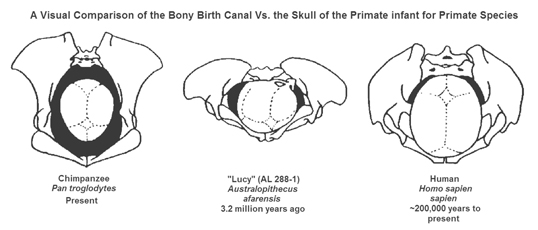

Our societies grew smarter and to keep up with all that knowledge so did we, growing ever bigger brains. But at some point we maxed out on brain size. At some point it became too dangerous to give birth to a bigger brain. Human childbirth is incredibly painful because human heads are incredibly large compared to the size of the birth canal. We can see this clearly by comparing the ratio of a baby's head size to the size of the birth canal for chimpanzees, an ancient hominin, and modern humans as illustrated in the image below. We should all be incredibly grateful to our mothers for what they went through to ensure our existence – they faced a more horrifying, difficult, and dangerous ordeal than any other great ape. More so if you have a bigger head!

Head size vs birth canal of Chimpanzees, ancient hominin Australopithecus, and modern humans. Source: ArchaeoMouse (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:A_Visual_Comparison_of_the_Pelvis_and_Bony_Birth_Canal_Vs._the_Size_of_Infant_Skull_in_Primate_Species.png)

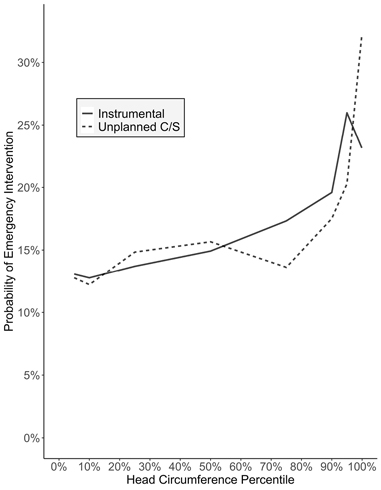

Bigger heads predict emergency cesareans and instrumental deliveries better than big bodies. Head size doesn't vary that much, but even within this limited variation, once you get to about the eighty-fifth percentile in head size, the need for emergency interventions hockey-sticks upwards on the graph. Big brains are great, but only if you can safely birth them. This variation and difficulty birthing big heads suggest that big heads are still under selection in humans. Basically, our species would like bigger heads like those Roswell aliens, but they're too difficult to birth. At least without a cesarean.

Head size as a predictor of emergency instrumental interventions (e.g. forceps) and emergency cesareans. Data from: M. Lipschuetz, et al. (2015). ‘A Large Head Circumference is More Strongly Associated with Unplanned Cesarean or Instrumental Delivery and Neonatal Complications Than High Birthweight’, American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 213(6), 833–e1.

The use of cesareans is increasing. In the last couple of decades it's gone up from around a quarter to a third in the United States and has doubled worldwide. The use of cesareans and other birth interventions will likely lead to larger-brained humans in the future and an increased necessary reliance on medically supported births. That is, eventually, most people may have heads too big to birth vaginally. Maybe those long-limbed, big-headed stereotypical aliens are actually humans from the future!

For our species, thanks to our huge heads, vaginal births are painful and risky to both mothers and babies. Historically, up to one in every hundred mothers died during childbirth. But cesareans too come with a cost – to the mothers, who are often confined to bed for several weeks afterwards and can suffer infections and long-term complications as a result of being cut open in a major surgery – and to the babies where earlier births may be associated with cognitive and health issues. Cesareans in general can also lead to early respiratory issues. Labor leads to fluid absorption with a final vaginal squeeze removing fluid from the baby's lungs. Cesarean births also have reduced microbiome transfer, which may reduce overall health outcomes. The bacteria in a mother's vagina seeds a baby's microbiome during the birthing process. These are problems that cultural evolution may eventually solve. Indeed, new techniques are emerging that may help mitigate these risks, such as slowing the cesarean procedure – a so-called natural or gentle cesarean – and vaginal seeding, which involves a saline-soaked gauze in the vagina then being swabbed on the baby soon after birth to transfer the mother's microbiome. Birthing humans isn't the same as it is for other animals.

With all the challenges that bigger heads bring, we are lucky that big brains aren't the only game in town to deal with growing information. The law of evolution can try different strategies. For example, you can just spend a longer time learning – by extending your childhood.

If you are asked to make a face like an ape, what you often do is puff out your lips or cheeks. What you're really doing is protruding your jaw. Humans resemble juvenile chimps who don't yet have this prominent protruding jaw. Evolution extended our childhood and kept us as juvenile apes – what's called ‘neoteny’.

Neoteny is a relatively easy change for evolution to make – a small change that in some sense extends features of childhood. We've done it to dogs, turning wolves into permanent puppies. We are the childlike chimp.

Neoteny might also mean that we're less aggressive, much as a younger chimp is less aggressive than an adult. It's a kind of self-domestication. Neotony might also explain why we can continue learning like a child for longer – with more to learn, we had to spend longer learning. Our childhood extended and a new period emerged: adolescence.

Adolescence is the period between the onset of puberty and full adulthood. The age at first birth and general preparedness for ‘settling down’ – finding a home and a job to support a family – have been increasingly delayed, creating what we could call kidults and a kind of cultural adolescence. What was initially a genetic extension of childhood has become a cultural extension where adults have no choice but to live with their parents because they're unable to afford a house of their own.

The world has also become more competitive. Even in our lifetimes, it used to be that a high-school degree was enough to compete in the workforce. Then any university degree. Then a STEM degree. Then a masters degree. Now a masters degree and one or more sometimes-unpaid internships. That's a long time to stay in school, and has created a new selection pressure: not just the ability to give birth to a big head but the ability to give birth at an older age. Those big heads and long childhoods have completely changed our societies. Starting with the relationship between men and women.

Premature babies, sexual norms, and child support

As our kids grow older, my wife Steph often marvels at how much they've grown, saying ‘I can't believe they used to be small enough to fit inside me!’ A fully grown human head is just too big to birth, but so too is the head of a young child. So humans solve the problem by giving birth prematurely. I don't mean some babies are born premature; I mean all of us relative to many other animals are born well before we're really ready to survive in the world. The vast majority of brain growth happens after you're born. As a father of three, I can assure you, human babies are floppy, useless messes.

We're not like a gazelle, ready to run. Or even like a baby chimp who still has a lot of brain growth left but can at least cling to their mother, easily drink milk, and will quickly mature and do even more. In stark contrast, our babies are wholly dependent on our care. We get less floppy and less messy as we get older, but we remain useless and reliant on our parents for a very long time. Some longer than others.

Our big heads, long childhoods, and protracted uselessness created new problems for our species. For one thing, our mothers need a lot more help with the kids. Today, in some societies there is still subsidized institutionalized childcare and support for single mothers providing a form of cooperative child-rearing. But another way to handle the problem is to get dad involved in protecting, provisioning, and otherwise raising children. This may seem like a natural solution, but it's highly unusual among great apes. Even among primates more generally, males typically don't have a lot to do with their offspring. It was a smart move getting dad involved, but remember genes are keen to spread themselves, so dad was happy to do it if it meant his floppy, useless kid was more likely to survive. But he also wanted to make sure that the floppy, useless kid was actually his.

One common solution to incentivizing human males to become doting dads was giving them greater control over female sexuality in return for greater control over male resources. Even today, female sexuality is more often the subject of normative control and the overwhelming majority of child support providers are male. But the control-support solution isn't the only one.

The Mosuo live at the Sichuan border with Tibet and are a rare example of a very different solution to the premature baby problem. Among this ethnic group there are no dads. Instead, your mother's brothers are expected to look after their sisters’ children and there is no expectation for children within a nuclear family as we think of it. Females have complete choice over whom they sleep with and genetic fathers don't have prescribed obligations. Instead it is the job of the uncle to fulfil the role of father.

The Mosuo solution works in terms of genetic relatedness. Brothers have a guaranteed 12.5 to 25% genetic relatedness on average to their nieces and nephews (depending on whether it's their half-sister or full sister). Compare that to a value of either 0% or 50% on average depending on whether a child is yours or not. For a male, the expected value of genetic relatedness is the probability of it being yours multiplied by 50%. The Mosuo solution is also upheld by norms, but very different norms from those in our society. But this solution isn't easily applicable outside the Mosuo context. It works, in part, because of the remote location of their community – people live in the same community and it's not easy to leave or join. You also have to have large enough families to make sure you have a brother.

The Mosuo solution may be rare, but it is one of the many ways in which our big heads reshaped marriage and mating everywhere in the world.

Traditional marriages

The Mosuo are an unusual solution, but so too is the modern Western nuclear family. In much of history and still in many places, polygyny (one man, many wives) was and is the norm. President Jacob Zuma of South Africa, for example, had four concurrent wives, rejecting monogamy as a Western tradition. But even in societies where polygyny is the norm, most men had, at most, one wife. Only the wealthiest, most powerful men, like a chief or president, had more than one wife. But this created a problem.

The number of girls born tends to be the same as the number of boys born. So if one person marries more than one wife, then someone else doesn't have a potential spouse. In WEIRD societies, we still tolerate ‘monogamish’ behavior, particularly among the powerful. There is some degree of unfaithfulness, perhaps even long-standing unfaithfulness, but what we don't allow is for one man to legally, and often normatively, take more than one wife at a time.

Monogamy as a norm and as a marriage law is an evolutionary mystery for the following reason. If we consider it in terms of pure economic utility, what's called the polygyny threshold model, in an unequal society a woman maximizes resources for her children and is economically better off with half or even any reasonable percentage of a billionaire than 100% of a man who earns $20,000. Such a society offers a more efficient allocation of male resources, assuming males hold most resources and there is inequality. But it creates side effects that destabilize a society.

First, it drives down the age of marriage for females. As wealthy males monopolize the mating market, eventually there aren't any more females to marry. Therefore, in order to gain more wives, they have to marry younger females. This in turn has further effects on the relationship between males and females that are counter to our sense of twenty-first-century Western moral norms.

Another problem that it creates is a pool of young, unmarried males without the hope of finding a spouse. Males commit most of the violent crimes in every society, young males even more so. So what happens when young males are involuntarily celibate because they can't access enough wealth to woo even one spouse? They take large risks to acquire that wealth, even through unethical and violent means. Polygyny is a recipe for a violent, unstable society.

Monogamous committed romantic relationships, such as marriage, domesticate men, literally reducing their testosterone. In societies that practice polygyny, different strategies have been used to deal with the young frustrated male problem. These strategies range from elaborate rituals that force men to bide their time before finding a bride, to encouraging these young men to partake in raids on neighboring communities. These raids may result in a man finding a wife among the women, stealing sufficient resources to woo a woman from his own community, or dying during the raid. All outcomes effectively solve the problem. Although polygyny is common, polyandry – where one woman has multiple husbands – can also solve the premature baby problem.

Polyandry is rare but occurs where resources are scarce and it requires more than one man to provision a single child. To solve the paternal uncertainty problem, a woman will often marry brothers so any child has some relatedness to all fathers. Polyandry is also sometimes supported by beliefs such as partible paternity – the belief that sex with multiple men is required to make a successful child. In these societies, pregnant women will seek out the best hunters, fishermen, or other skilled artisans to endow their child with their abilities. In turn, these men may consider the child their own, providing some amount of care and resources that they wouldn't otherwise.

All of this is to say that the cultural evolution of mating practices is not constrained per se, but is affected by our biology, technology, and the environment. But ultimately, all practices are trying to solve the same problem – the big-headed premature baby problem. Indeed, it was our big heads that gave birth to the patriarchy.

Origins of the patriarchy

Matriarchy in the strictest sense refers to a society led primarily by women. By this strict anthropological definition, no matriarchy has ever existed in human history. But that doesn't mean all societies are equally patriarchal.

Even among societies that still practice traditional ways of living, some are more egalitarian than others. The Khasi people of north-east India, for example, are matrilineal and matrilocal. Matrilineal means that descent and inheritance are traced through the female line. Orthodox Jews are a well-known example of matrilineal descent. Matrilocal societies are those in which a husband is expected to live with their wife's family. Matrilineal societies represent a little less than 20% of contemporary traditional societies. These structures of our society affect our psychology.

Men are often assumed to be the more competitive sex, but experiments reveal that Khasi women are more likely to compete in an experimental game than Khasi men (54% vs 39%), showing levels of competitiveness similar to Maasai men. The Maasai are a highly patriarchal society, recognizable for their height, red robes, and impressive vertical leaps. Among the Maasai, 50% of men and 26% of women chose to compete. These numbers also reveal the enormous individual variation between people in every society around the world.

Such differences are also found in post-industrial societies. As I write (2021), the current defense ministers of Denmark, Netherlands, Germany, Austria, France, Spain, Belgium, Switzerland, Czechia, Montenegro, and Canada are all women. In contrast, the United States has never had a female secretary of defense let alone a female commander in chief. Neither have Russia nor China in their equivalent positions. How can we explain these patterns?

As we've seen, males and females have some reliably developing differences. One of those is strength. In fact, the average man is stronger than 99% of women. As humans transitioned from a hunter-gatherer lifestyle to agriculture, they developed different agricultural technologies and practices, such as the plow and pastoralism.

The plow was not equally useful everywhere. It's difficult to use on shallow, sloped, or rocky ground, and is particularly useful when large plots of land need to be prepared quickly. It's also more useful for certain crops, such as wheat, barley, rye, and rice. Plowing, even with the help of an animal such as an ox, requires a lot of strength. Males therefore have a natural physical advantage. In contrast, hoeing can be done by males or females. Using climate and geography as an exogeneous source of variation, research reveals that not only are traditional hoe-based societies more gender equal than plow-based societies, but even long after most people have given up farming the descendants of plow agriculturalists continue to have more gendered ideas about the appropriate roles for men and women. This is even true among second-generation migrants who immigrated to countries such as the United States.

The theory of everyone offers a powerful tool for discovering the origins of sex differences. For example, it allows researchers to look for practices that exacerbate the premature baby problem. One example is pastoralism – herding animals.

Pastoralism requires men to be away from their families for long periods of time as they take their cattle to new pastures. Being away from their partners increases paternal uncertainty. Pastoralist dads are even less likely to know if a baby is theirs. This in turn heightens the compromise between controlling female sexuality and male resources. These dynamics shape the environments in which children are raised and in which their cultural package is delivered to them. Part of that package are norms such as gender attitudes.

Researchers such as economist Anke Becker have found that pastoralist practices and ecological determinants of pastoralism can cause increased female genital cutting, stronger restrictive norms around female promiscuity, and even restrictions on female mobility, such as women having to ask for permission to leave the house and requiring a chaperone when out of the house. These norms are not only imposed by men on women – indeed men are often away so cannot enforce the norm – but instead permeate the society – women are often the enforcers.

Humans became a socially learning cultural animal. This led to us having too much to learn requiring bigger brains. Those bigger brains meant that we were born premature, floppy, useless messes, which in turn meant mothers needed to spend longer caring for their babies. That in turn required more support from their communities and from fathers. Fathers needed to know that the baby was theirs to allocate resources, time, and forgo other mating opportunities. This package completely reshaped our societies in different ways, but ultimately all that cultural variation was grounded in the same reality. Having too much to learn also co-evolved with the ability to speak.

Learning to speak

As the tree of knowledge grew, we became addicted to eating its fruits. We used that knowledge to innovate better ways to unlock energy and better ways to survive, and so we could support larger numbers of people with larger calorie-consuming brains. More calories, more people, more opportunities to innovate, more to learn. And so we got better at dealing with this ever-growing body of information. One major advancement was the evolution of language.

Language is the most powerful invention for information transmission. I'm using it right now to deliver this information to you. Language is sometimes invoked as what separates us from other animals, but language is not an explanation for the successful human package, it's part of the puzzle. Here's the thing: there's no point having a language that only you can speak.

Language is a coordination problem – others have to understand and speak your language for it to be useful. So you also have a start-up problem. In the beginning no one knows how to speak. In fact, they lack the ability to speak – they don't have the cognitive circuitry. All attempts to teach other apes language have failed. The most we've achieved is simple sign language or language boards, which non-human apes use only to make requests, which is slightly more sophisticated than what your dog does when it's hungry. This start-up problem is sometimes called a bootstrapping problem – a circular dependency, in this case, language requiring others to speak it before it is useful. The term comes from the impossibility of pulling yourself up by your own bootstraps. So something had to happen to kick it all off. Before we could invent and strap on any boots, we needed to walk on two legs. For language to evolve, we needed to become bipedal.

Bipedalism may have been a critical preadaptation for the evolution of language. The nice thing about being bipedal is that it frees your hands. Freeing your hands did a couple of things. First, now that your hands are free, if you have information worth transmitting, you can supplement your crude guttural utterances with gestures. Even today, wild hand-waving isn't restricted to Italians. We can't help but gesture as we speak. The combination of a proto-language and information worth transmitting could then kick off what's called a Baldwinian process. The Baldwinian process was proposed by evolutionary biologist James Baldwin (no, not the writer and activist). It's a specific culture–gene co-evolutionary process that might currently be happening with reading. Here's how it works.

If something important and adaptive enough can be learned then genes that help you learn it better can be selected. So in this case, small mutations that improved how quickly I could learn and understand more hand gestures or guttural grunts would be selected as long as the information I was getting from those gestures and grunts was useful enough to help me survive. Today, reading might fit the same category, but back then it was just learning to speak.

With enough information worth communicating, when mutations that made us more articulate – like the gene, FOXP2 – emerged, they were selected. Some of those mutations changed our throats, giving us language. They also made us more susceptible to choking. We were literally dying to speak to one another, revealing the importance of language and communication. So freeing up our hands through bipedalism bootstrapped language by giving us another medium through which to communicate. Bipedalism and freed hands were a double win. They also led to more stuff worth communicating – like fire and tools.

By freeing our hands we could not only speak through gestures but also make better tools. Free hands also cheapened the cost of those tools. Walking on all fours makes it difficult to carry tools. A quadrupedal animal like a chimp doesn't want to invest too much time or effort in making a tool, because they'd need to make another one when they move: who wants to carry a big stone axe around on all fours! But a bipedal species can carry tools with them and so can afford to spend more time literally sharpening their stone axe – and learning how to do that.

We see the first stone tools around 2.6 million years ago. What we don't see are the bone and wooden tools that probably predate the stone versions. Wood and bones don't survive the passage of time quite as well as stones. Just as chimps fashion wooden tools today so our ancestors probably did too. Even in the absence of this direct evidence for early tools, we do have evidence for something else worth transmitting that was critical for our species – fire.

We see evidence for fire 1 to 2 million years ago, but adaptations suggest we had access to fire to cook our foods for a lot longer. The evidence is our short guts and weak jaws, suggesting the presence of predigested, softened, cooked foods. Remember, we can't survive on raw food alone. Today's raw foodists rely on large quantities of available foods and a range of supplements. Just as in the future we may need the cultural invention of cesareans to reproduce, back then, we needed the cultural invention of fire to eat.

I'm not sure if you've ever tried to light a fire without being shown a technique or without access to technologies like a lighter, matches, or Swedish FireSteel – it's hard. Really hard. And so fire-making skills would have been invaluable – indeed essential – adaptive knowledge to transmit, given that our growing brains needed the calories unlocked by cooking. Fire increased the EROI and raised the energy ceiling for early humans, and so passing on the innovation of fire-making and tool-making probably helped support the evolution of language. So we had something worth transmitting (fire and tools) and by becoming bipedal we had a new medium to speak (gestures). This would have been enough to kick off a co-evolutionary Baldwinian process that would eventually lead to our current full-blown language abilities. But who taught us? Maybe mom and dad? Or maybe many moms and dads.

It took a village

Young chimps learn from their mothers because that's who they get to spend the most amount of time with. Indeed, more females in a chimp society are associated with a larger cultural corpus. But unlike chimps, there is some evidence that humans may have been cooperative child rearers, helping each other raise their children. Ever heard the phrase ‘It takes a village to raise a child’? It's true. And for most of human history, we probably had a literal village.

Cooperative child-rearing not only made it easier to look after big-brained children with long childhoods, but also removed a key constraint that chimps have in learning from one another – who they have access to.

Chimps learn to crack nuts with rocks, sponge water with a wad of leaves, or fish ants with sticks from their mothers, because that's who looks after them most of the time. But our ancestral cooperatively child-rearing humans had many aunts and uncles serving as many moms and dads. And so we could begin to learn who the best and smartest teachers were – Aunt May or Aunt Martha?

In contrast, parenting is harder for modern parents, not only because there is so much for our kids to learn but because we often don't have that ancestral village to provide cooperative child support. But even today, cooperation in child-rearing is essential. Lacking our traditional village, we've institutionalized that cooperation through paid childcare and schools. We've also improved our ability to educate with specialized teachers, writing, radio, television, the Internet, and online courses. But before there were specialist teachers and online masterclasses, our cultural nature evolved the first professors: grandmothers.

Information grandmother hypothesis

Humans are not alone in placing great importance on older females – elephant grandmothers lead their herd, playing a critical role in the survival of their grandchildren. Humans are also not alone in the presence of menopause. Several cetaceans, including orca and pilot whales, also have evidence of it. The common feature that seems to bind these grandmothering, menopausal societies is culture – socially transmitted information.

Grandparents and particularly grandmothers have played an important role in raising human children, teaching them, and helping them survive. Long before schools, books, and the Internet, grandparents were the major source of wisdom and knowledge accumulated over their long lifespan. Grandparents were the Wikipedias of their time. In a precarious world before we learned to write, the mere fact that a person lived to old age was evidence that they had skills and knowledge that could help children survive and reproduce.

Remember that you have been able to reproduce since your early teens, and in the past, prior to the cultural evolution of an extended adolescence, you might have done so. But you would have been a poorer parent, knowing less about how the world worked and still learning how to survive in it. This was also true in the past. It's only recently that young people can know as much or more than their parents and grandparents, a product of rapid technological change in sources of knowledge, particularly the Internet. The past was more stable with fewer places to figure out how the world works. Grandmothers of the past gathered food, cooked, and cared for their grandchildren, just as they do today. But kids weren't just getting a cook and babysitter, they were getting a chance to hang out with the professors of the past. Grandparents were the most brilliant members of their society.

Even today, grandparents naturally excel at delivering knowledge. Curiously, even with ageing-associated illnesses such as dementia, grandparents often retain the ability to be storytellers for a long time, as if making a last-ditch effort to pass on everything they know. As the large cohort of Baby Boomers retire, one way to help reduce the economic burden may be reinstating their traditional role as carers to the next generation. Intergenerational care-home-cum-childcare centers, such as Nightingale House founded and run by south-west London's Jewish community, offer a potential model with reported benefits for both children and the elderly. Every day at Nightingale House children and elderly residents come together to cook, read to each other, perform concerts, or play games. The children are supported in their learning and development and the residents seem to have better physical and mental health, including lower depression and loneliness.

Grandparents and other aspects of cooperative breeding were a way for humans to innovate and explore the space of the possible. But the law of cooperation discovered so many more solutions to get us to work together. By capturing more energy, we bound ourselves into larger bands, expanding the moral circle of whom we care about well beyond family and friends.