6

Cooperation

We are now in the final chapter of Part I. We have seen what a theory of everyone has revealed about our control over energy, our intelligence, our innovation, our brains, our bodies, and our societies. But all of this is contingent on one thing: our ability to work together. The four laws of life interlock. Our control over energy and ability to innovate are empowered by our ability to cooperate.

Over the last two and half centuries we have seen an explosion in energy control, innovation, and population. Former enemies have become friends, and the previously oppressed now work together with former oppressors. We are cooperating at heights that would have been unimaginable to even our recent ancestors.

How did we achieve cooperation at the scale of large unions of nation-states like the United States and European Union? Answering this question is essential to ensuring that cooperation and all the progress we have achieved thus far doesn't come crashing back down. In Part II we will zoom out to see the threats to cooperation and what we need to do to overcome them, but first we need to zoom in and understand the specifics of how we got here.

The puzzle of cooperation

I'm often asked to give talks at universities, for companies, and in public settings around the world. As I'll remind my audience, putting large numbers of strangers together in the same room, or indeed inviting a stranger into their midst, is unusual.

It's unusual from a cross-species perspective: a room full of strange chimps is a room full of dead chimps. It's unusual from a historical perspective: even a few hundred years ago, a stranger was a potential threat and in danger themselves from those who felt threatened. Even today there are geographical variations: I would be a lot safer giving a talk in Switzerland than in Somalia. And yet there are many places around the world today that have created sufficiently stable, large, and diverse populations, peaceful for the most part, and with well-connected collective brains that support innovations that leave all of us better off. How did this happen?

This question is puzzling enough that even after decades of work, in 2005 Science magazine listed ‘How did cooperative behavior evolve?’ as a top twenty-five big question for the coming quarter-century. To understand the essence of the puzzle, we can go back to a now classic paper written in 1968 by Garrett Hardin. He called the puzzle the ‘tragedy of the commons’.

Hardin asked us to imagine a common, shared field that farmers use to graze their cows. The number of cows getting enough calories to thrive and grow is constrained by the size of that grassy field – its carrying capacity, if you recall. But how the field is shared requires mechanisms that support working together. Why? Because it is in the best interests of all the farmers to be careful with their grazing so the field will exist for many years. But it is in every individual farmer's best interest to graze their cows as much as possible so their cattle grow as large as they can. Cooperation requires finding ways to suppress that selfish urge. If your policy is to rely on goodwill alone then it's a bad policy, because between selfishness and altruism, all else being equal, selfishness wins in the end. Taking advantage of others is an easier and more efficient way to gain more resources. And so by the laws of evolution and innovation it is selfish mutations that will dominate over altruistic mutations.

You can see this dilemma in many spheres. The person in the office who free-rides by not doing their fair share or by taking credit for work done by others. It would be great if those behaviors didn't lead to career advancements, but they often do and that's why such selfishness persists. At an international level, climate-change mitigation is an example of managing the commons of our world. Yes, we would all be better off in the long run if we all agreed to cut back our carbon output. But as I mentioned at the beginning of this book, it was always unlikely that we would slow the economy to save the planet. In the absence of a global government or credible ways to enforce the carbon commitments made by other countries, every person, every company, and every country uses the energy they can afford. Even if a few cut back, they would be outcompeted by those that did not.

The tension is always between what is best for me and what is best for us. Or what is best for a smaller us over a bigger us. A society succeeds – and arguably only becomes a society – when it suppresses the tendency to be selfish and moves to a new equilibrium that incentivizes people to be more altruistic. In working together, if there is energy to be exploited, a society can unlock more energy and resources to expand. It can not only manage the field Hardin imagined, it can grow it.

To study these cooperation dynamics and the behaviors of people in different places and under different conditions, scientists often use economic games related to the tragedy of the commons. Each game changes the pay-offs of different decisions to capture different facets of the cooperation puzzle. Take for example the public goods game.

In the public goods game, people are given some money which they can either contribute to a public good or keep for themselves. The money contributed to the public good is multiplied and then shared equally between all players. You can think of it like paying your taxes for things we all enjoy, such as clean air and water, roads, firefighters, and police officers. In these cases and in the game, you are personally better off by not contributing, not paying taxes, and instead free-riding on the contributions of others, even if we would all be better off if everyone paid their fair share of taxes.

Data from public goods game experiments reveals that people play close to the cooperation norm in their society. At least at first. In WEIRD societies, people's first instinct is to cooperate, and they often only play selfishly after thinking about it and realizing there's more money to be made by not contributing. Instinctively being cooperative makes sense when we're surrounded by other cooperators. But if you grew up around people who were trying to exploit you, you would instead be intuitively skeptical and perhaps intuitively selfish.

Cooperative behavior can easily be overwhelmed by selfish behavior. Unchecked selfish behavior is the Nash equilibrium – the optimal, highest pay-off strategy that will dominate with no counteracting forces.

Even in these games, after an initially cooperative decision, players slowly realize that just by being a little bit more selfish they can make more money and eventually, over subsequent rounds, they reduce their cooperative contributions to the public good. They slip backwards into selfishness. These experiments are a sped-up version of what happens in our societies.

Even in the most cooperative, wealthy industrialized societies, we are always in danger of slipping backward toward selfishness and conflict. Many people prefer to avoid taxes if they can – money under the table, tax loopholes, offshore havens – which in turn leads to more people avoiding taxes if they can. No one wants to be the chump contributing for others to benefit when others are not paying their fair share. So the question is always, what's stopping everyone from doing this? The answer is the various mechanisms of cooperation that have been discovered in answer to Science magazine's challenge.

Mechanisms of cooperation

Even before Science magazine laid down its challenge, biologists, economists, and psychologists had identified various mechanisms that incentivize cooperation over selfishness. These mechanisms had limits to how much cooperation they could achieve and with whom. Only today do we have a more complete picture of how animals cooperate and how humans have reached the heights of cooperation we've achieved. For humans, the lowest level of cooperation is between family members.

Loving families

A common cliché is that love is a mystery. That the bonds of family are hard to explain. Perhaps this was once true, but we now have a deep scientific understanding of both love and the bonds of family.

This explanation is what's called inclusive fitness or kin selection, and it's the most basic level of cooperation. It explains why grandparents are willing to teach their grandchildren, why we love our kids, and why all animals, if they favor anyone, favor their kin. It's the reason a lion might kill another lion's cubs but rarely their own and the reason your own baby crying is tolerable while another baby crying is miserable. The basic idea is captured by a joke made by biologist J. B. S. Haldane.

A friend asked Haldane, ‘Jack, would you lay your life down to save your brother?’ Haldane only had a sister, but nevertheless responded ‘No.’

‘But,’ he continued, ‘I would save two brothers or eight cousins’.

What Haldane was getting at was an evolutionary logic later formalized by Bill Hamilton in 1964. It's the E = mc2 of evolutionary biology: rb>c. The basic logic is as follows.

At a genes-eye level, genes that can make more copies of themselves will outcompete genes that make fewer copies of themselves. That's what Richard Dawkins meant when he described genes as selfish. One way for the genes to make more of themselves is to convince you to have children – that's the standard logic of natural selection. Your children have 50% of your genes. But other people around you don't have 0%. My brother, Daniel, was surprised when his gene sequencing results revealed that he had a half-brother who shared 25% of his genes. That ‘half-brother’ wasn't a half-brother at all but my son, his nephew, Robert.

So, genes can also spread themselves by identifying and favoring other less-related individuals who carry copies of the same genes, such as your nieces and nephews and also more distantly related relatives. But evolution also shapes the amount of support you will provide to relatives. Daniel should provide a lot of support to his identical twin brother, Chris, and more to his own children than to his nieces and nephews. More formally, the rule is that when the relatedness (r) times a benefit (b) to the family member is greater than the cost to yourself (c), then you should cooperate. And more so when either the relatedness and/or benefit terms are much larger than the cost to yourself.

Inclusive fitness is the mechanism that gets humans to the level of cooperation among relatives – those hunter-gatherer bands that persisted for thousands of years. But it doesn't explain the kind of cooperation we see among humans today. We regularly cooperate with strangers. Inclusive fitness and kin selection can be trumped by direct benefits to yourself.

An eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth

A more powerful mechanism for larger-scale cooperation is referred to as direct reciprocity, reciprocal altruism, or peer punishment. It can be summarized by the adage ‘You scratch my back and I'll scratch yours’ or ‘An eye for an eye; a tooth for a tooth’. Remember the laws of life: ultimately, we're not cooperating for no reason, we're cooperating to efficiently access energy and resources. And often it pays to network and trade favors, helping those who will help you in return.

Direct reciprocity gets you to cooperation at a village level or the level of a workplace. It's what explains friendships. Other animals also cooperate through direct reciprocity. As long as everybody knows everyone else and they regularly interact, they will help those who help them and harm those who harm them. You don't even have to like the other villagers or your office colleagues to cooperate with them. The promise of returned favors or the threat of retaliation is enough for people to get along. But direct reciprocity suffers from some problems.

First, it requires an ongoing relationship. You have to have some reasonable probability of having a favor returned or you're being exploited. Con artists don't try to con the same community – they'd get caught; they have to move on and find another mark.

A second problem is that the direct punishment aspect can lead to cycles of retaliation for punishment – as Mahatma Gandhi put it, ‘an eye for an eye makes the whole world blind’. And a final problem is that because direct punishment often comes at a cost to the punisher, it also suffers from the second-order free-rider problem. Not that people are unwilling to contribute to the public good, but that they're unwilling to pay the cost of punishment when others do not.

Imagine you're waiting in a queue. Someone skips the line ahead of you. It makes you mad. Someone should tell them off! But hopefully someone other than you . . . Do you really want to face potential retaliation or harm? But if no one is willing to enforce the norm, eventually queues collapse into throngs as queue-jumping becomes more frequent.

But even when these problems are overcome – which, as I mentioned, they mostly are in small communities, including nonhuman communities – direct reciprocity still doesn't get you to the level of cooperation in a modern large-scale anonymous society where you don't know or regularly interact with everyone in your country, city, or even neighborhood. We need something more.

Reputation is everything

Beyond direct reciprocity, we can use indirect reciprocity – cooperation conditional on a good reputation. For direct reciprocity you personally need to know someone and regularly interact with them to know if you'll have your favors returned. But for indirect reciprocity, you don't need to know everyone, you just need to know of them. You need to know their reputation so you can conditionally cooperate with those who have a reputation for cooperating back and conditionally avoid those who do not. In doing so, you can improve your own reputation.

Think of gathering together a team for a company or project. Ideally, it's people you know and have worked with before (direct reciprocity), but to expand your network, you rely on whether someone has a good reputation. You ask around, listen to gossip, and in the worst case read their LinkedIn endorsements. This is actually why we evolved to love gossip so much – it's about tracking reputational information.

Indirect reciprocity requires that you know of people and have reliable information about them. If reputational information is uncertain or untrue then cooperation collapses, just as, if a review platform offered fake restaurant reviews, you would stop using it. Once again, at least prior to online reputation management, it's still not a powerful enough mechanism to scale up to a large-scale society of anonymous strangers.

Leviathan

The mechanism we encounter most often in the modern developed world is what we might call institutional punishment. Rather than relying on our genetic relationships, punishing people directly, or relying on reputation alone, we bypass all the challenges and difficulties of these mechanisms by instead paying our taxes to an institution that does the punishing for us: our governments, police forces, courts, and judiciaries.

Institutional punishment with the right rules is incredibly effective at stabilizing large-scale cooperation. But, while the right institutions can stabilize the high scales of cooperation we see today – and experiments reveal that people, at least WEIRD people, prefer them to these other mechanisms – anyone who's traveled, knows their history, or is keeping up with current geopolitics knows that institutions can be, and often are, undermined.

Institutions securitize trust. Rather than trusting one another directly, instead we place trust in our institutions to protect our interests and act fairly. This in turn increases our trust in one another, knowing Big Brother is looking out for us. But the trouble starts if our governments, regulatory bodies like the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), Food Standards Agency (FSA), European Medicines Agency (EMA), or Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), police forces and justice systems are not perceived as unbiased and impartial in their decision-making. The trouble starts if it feels like the law is selectively applied based on who you know, future favors, or direct financial rewards; when legal systems are undermined by lobbying, political patronage, and personal connections. Under these conditions, the power of institutions to sustain cooperation collapses. We call it discrimination, racism, and corruption. But what would cause institutions to become biased? What undermines this high level of institution-mediated cooperation? The answer may surprise you. The answer is cooperation.

Institutions are ultimately made up of people with competing priorities and cooperative commitments. All mechanisms of cooperation exist alongside one another – we have our family, our friends, our reputations. Altruism at one level is selfishness at another. Favoring your family over your friends; your friends over your local community; your local community over your state, country, or world – all are both cooperative and corrupt. And so higher scales of cooperation – such as nations – can be undermined by lower scales – such as family and friends – if these are not suppressed. Examples abound.

Family dynasties in unstable developing countries that enrich themselves at the expense of the common good are ultimately kin selection undermining institutional punishment. From a Western vantage point it may seem like such corruption is a failure to be explained, but it is not. Corruption is far more natural than impartiality. The puzzle is how we overcame it in some places, but not in others.

From cooperation to corruption

There is nothing natural about democracy. There is nothing natural about living in communities with complete strangers. There is nothing natural about large-scale anonymous cooperation. But there is something very natural about prioritizing your family over other people. There is something very natural about helping your friends and others in your social circle. And there is something very natural about returning favors given to you. These are embodied in cultural obligations such as Western old-boy networks or Eastern guanxi. These are the mechanisms of cooperation found across the animal kingdom.

When a president negotiates his son a government contract, we call that nepotism. But it's also inclusive fitness undermining institutions. When a manager gives a job to a friend or a friend of a friend not because of private information but because of the relationship, we call this cronyism. But it's also direct or indirect reciprocity undermining our meritocracies. Bribery is a cooperative act between two people, and so on. It's no surprise that India, China, other parts of Asia, as well as much of Latin America – all family-oriented cultures – are also high on corruption, and particularly, you guessed it, nepotism.

We often think about supporting our families as a virtue, but when it really is the case that la famiglia è tutto – when family is everything – that might also be at the expense of a more impartial and fair society. The norm of looking out for your kin over others prevents countries from reaching a better outcome for everyone, an outcome where even those without strong connections can thrive. These are some of the aspects of culture that are the invisible pillars that support successful institutions.

Institutions rest on invisible cultural pillars

It doesn't matter that the law says you must be impartial if the norm is to favor your friends and family. It doesn't matter what the constitution says if you don't have a norm around the rule of law that enforces the idea that not even the leader is above the law. Successful institutions require that we are ruled by principles and not by people. And these norms vary around the world.

A dilemma posed by Dutch psychologist Fons Trompenaars captures this normative difference.

You are a passenger in a car driven by a close friend, and your close friend's car hits a pedestrian. You know that your friend was going at least 35 mph in an area where the maximum speed was 20 mph. There are no witnesses. Your friend's lawyer says that if you testify under oath that their speed was only 20 mph then you may save your friend from any serious consequences. What would you do? Would you lie to protect your friend? What right does your friend have to expect your help? On the other hand, what are your obligations to society to uphold the law?

When people around the world were asked this question, their answers differed dramatically. The majority of Koreans, Russians, and Chinese said that they would lie for their friend. But over 90% of Swiss, Canadians, Americans, Swedes, Brits, and Dutch said that the friend has no or only some right to expect support and that they would not help.

Impartiality and rule of law are two of the many norms that are essential to well-functioning democratic institutions. When a country discovers the all-too-common phenomenon of a corrupt leader absconding with billions in national funds that could instead have been used to build better schools, hospitals, and roads, they question why less-corrupt leaders can't be found. But corruption is not a function of bad leaders that can be replaced by better leaders; it's a function of entire cultures where the same behavior of favoring friends, family, and close connections occurs at every scale: from the manager giving her friend a job, to an official allowing a connection to skip the usual bureaucratic process, to the minister giving his nephew a government contract. The difference here is not in the behavior but in the scale of the implications.

Even within Europe, we can see differences in impartiality from surveys of the method people used to find their current job. In Switzerland, Germany, and Norway, people primarily found jobs through job adverts. Job adverts level the playing field and create a larger, fairer competition by being available to all. In contrast, in Portugal, Italy, Greece, and Spain, which are all higher in corruption, people primarily found their job through friends and family.

Norms such as individualism and impartiality rather than familial obligations co-evolved with democratic institutions, largely in Europe. But as these within-Europe results make stark, they are hard to fully implement and countries are always in danger of slipping back to these more natural, lower scales of cooperation. This is also why it's such a challenge to try to export democratic institutions and fairer, impartial, non-family corporations to places around the world that lack these necessary norms.

Liberia, for example, founded by formerly enslaved Americans, took more than its flag from the United States, but is now by almost all metrics on the other end of the spectrum in the strength of its democracy, human development, corruption, and violence. The institutions alone were never enough. You also need those prerequisite cultural pillars. But like Wallace's water, those pillars are invisible to those from successful, less-corrupt countries. Unless you've lived in a country without these pillars, it's hard to fathom the difference in psychology, norms, and institutions. This failure to understand the diversity of people, how they handle relationships, and the different normative obligations in other nations has had disastrous consequences for foreign policy. Take, for example, the failure to transplant democratic institutions to Afghanistan.

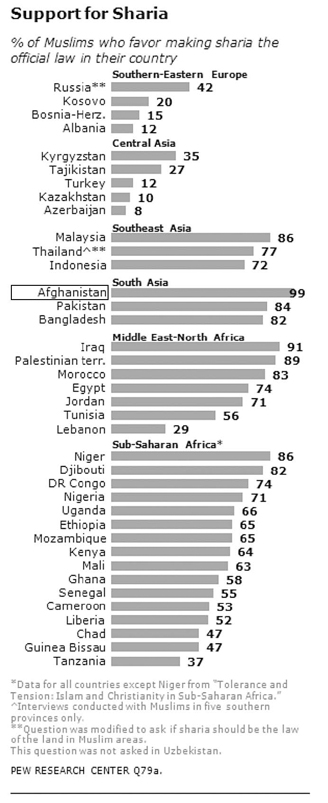

Source: ‘The World's Muslims: Religion, Politics and Society’, Pew Research Center, Washington, D.C. (2013), https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2013/04/30/the-worlds-muslims-religion-politics-society-overview/

Lessons from Afghanistan

In the wake of the 2021 Taliban takeover of Kabul, President Biden defended his decision to withdraw US troops from Afghanistan saying, ‘We gave them every chance to determine their own future. What we could not provide them was the will to fight for that future.’ But did Biden really understand what type of future Afghan people actually wanted? The little data we have, supported by deeper historical context, suggests that it was not the one imagined by those in charge of US foreign policy.

The United States occupied Afghanistan in 2001. At the height of this occupation, in 2013, a Pew poll suggested that 99% of Afghans favored making sharia the official law of the land – a figure much higher than any other Muslim country.

But the word ‘sharia’ simply refers to Islamic law and can mean different things to different people. So what did the specific policy questions tell us?

- 81% of Afghans favor corporal punishment, such as lashings and cutting off hands, for theft.

- 84% favor stoning as the punishment for adultery.

- 79% favor a death penalty for leaving Islam.

Pew claimed the data was representative of the population, but in certain areas women were under-represented. It is possible that even if the interviewer were a woman interviewing an Afghani woman with no man present, women may nonetheless have answered with the perceived norm, as may have Afghani men. And neither men nor women may have had a good concept of alternative laws and norms. Indeed, in larger cities, we can see more (though still a minority) of women lobbying for greater rights. On the other hand, these numbers from Afghanistan are not small majorities. And moreover, many other norms and conditions in Afghanistan also pose challenges to successful democratic institutions.

Afghanistan, a nation of over a dozen tribes with different languages and histories, cooperates primarily at the level of kin. People rely on their kin for survival through support and favors. Afghanis even marry among their extended family – the rate of cousin marriage in the country is 46%. Kin-based obligations undermine the kind of impartial institutions that liberal democracies require. Instead, partisan, tribe-based politics dominates. It becomes critical that your person and not necessarily the best person is in charge. These dynamics unsurprisingly undermine good decision-making. And unfortunately, these norms are self-sustaining.

People rely on their friends and family and place great importance on these relationships, because they can't rely on governments and other institutions to support them. In such places, people prefer cash, take loans from family rather than banks, and are less likely to engage in broadly pro-social altruism such as donating blood or impartial charitable donations to strangers. For many in such places, charity starts at home, but that's also where it ends. These countries are trapped in a self-sustaining equilibrium that prevents them from reaching higher scales of cooperation.

The aforementioned Afghani data can be hard to understand let alone accept if we've never met people who hold such views. When this data is shared with people in WEIRD countries, it is often met with instinctive incredulity and sometimes moral outrage at the idea of such cultural differences. The very idea that people might want something so drastically different to WEIRD sensibilities sometimes invites patronizing and paternalistic attitudes – that people in other societies just don't know better. Regardless, this attitude contributes to failed foreign policies in these distantly different cultural contexts. If you read this section with surprise or incredulity consider that even if one accepts a diluted version of the data, the point still stands – the rights and rules commonly found in WEIRD societies may not be what everyone everywhere wants. And successful foreign policy requires full understanding of the norms and values of people in other nations. But of course, even if we narrowly focus on economic development, the WEIRD package of norms and institutions may not be the only one that works for large-scale cooperation and economic development. The law of evolution just happened to discover these ways of cooperating as an adjacent possible of Europe's specific historical trajectory, as we will see in the next chapter. In other words, other solutions are also possible. Many nations, most notably those in Asia, have borrowed and recombined elements of successful WEIRD institutions and adapted them to local cultures and circumstances.

South Korea, for example, has successfully and in their own way integrated WEIRD-style corporations and institutions. Hong Kong, as a former British colony, was an engine of development for China and is culturally halfway between China and Britain. These examples represent WEIRD-style corporations and constitutions tailored to more collectivist cultures. The overall message is that cooperation and conflict are two sides of the same coin.

As novelist Nafisa Haji quoting an ancient Arabic proverb put it, ‘I, against my brothers. I and my brothers against my cousins. I and my brothers and my cousins against the world.’ This is the evolutionary dance between cooperation and competition, the duality of the human condition.

Humans cooperate in groups – overlapping and embedded within one another – and then these groups sometimes cooperate and sometimes compete, depending on contexts and conditions. It is through strong competition in the presence of large energy sources that higher scales of cooperation are reached. The mechanism by which this happens is called cultural-group selection.

Cultural-group selection

Cultural-group selection describes competition between cultural-groups, which are defined as groups of cultural traits rather than groups of people who possess those traits, because people can change and acquire different traits over their lifetime. I use a dash in cultural-group to avoid ambiguity and the mistaken view that we are referring to some cultural form of group selection on groups of people. These cultural traits might include belief in democracy, female empowerment, hard work, arriving on time, giving to charity, which sports should get more funding, and much more. It requires a psychology to represent normative behavior, a psychology of reputation to reward those who follow norms and punish those who do not, and a psychology to identify groups and subgroups who may have different norms.

In the strictest version of cultural-group selection there may be a perfect overlap between the cultural-group of traits and the group of people, such as in an ethno-linguistic group. A small New Guinean tribe's unique beliefs may be completely correlated with its unique language. But this is rare. In most cases, we belong to multiple overlapping and embedded cultural-groups. For example, cultural-groups of liberal democracies and of shared religions; of Googlers and of Department of Defense employees. There are British Catholics and Spanish Catholics; Americans who are also New Yorkers; Amazon employees who span the globe.

There are a few well-studied mechanisms by which these groups compete, though there are probably many more yet to be discovered. The best-studied mechanisms include the following:

Direct competition: Groups outcompete one another through conflict or simply surviving at the expense of another group – e.g. war or corporate bankruptcy.

Selective, assortative migration: Individuals carrying cultural traits move to some places at a greater rate than others – e.g. more people move from South Africa to North America than vice versa. America as a cultural-group will grow at the expense of South Africa to the same degree these migrants or their descendants acculturate to dominant American values. If these migrants don't acculturate but instead change the local culture – perhaps South Africans Trevor Noah and Elon Musk brought values, norms, beliefs or behaviors that other Americans now embody – then they represent cultural mutation or recombination (think Hawaiian pizzas). If they segregate as separate communities, a satellite to their group of origin, then they represent a smaller cultural-group, potentially competing within a larger one. If you choose to work for one company over another or people choose to stay or leave during a merger or acquisition, these too are examples of selective, assortative migration.

Demographic swamping: Some groups grow faster than others. For example, agriculturalists at the expense of hunters and gatherers; pro-fertility religions emphasizing large families at the expense of religions that did not emphasize fertility; companies that secure more investment or larger profits.

Prestige-biased cultural-group selection: Groups copy the cultural traits of more successful or prestigious groups en masse. For example, Americanization or Westernization of many traditional communities, or the spread of hip-hop culture beyond its African American origins. Watching a Japanese hip-hop crew in Tokyo, I was struck that they had not only absorbed the musical style but also the hairstyles and fashion. And of course, companies borrowing policies and practices from more successful companies.

One of the clearest examples of cultural-group selection and the duality of cooperation and conflict is the evolution of religion.

The evolution of religion

To some non-Muslims in recent years, the Takbir, a short prayer of praise meaning ‘God is the greatest’ – ‘Allahu akbar’ – has instead become associated with violent terrorist attacks. Like the Takbir, religion itself, especially since 9/11, is often seen as a source of conflict. Indeed, it is a source of conflict. But it is also a uniquely human source of cooperation that bridges reputational psychology and Leviathan governing institutions. Religion was the ladder we used to climb from reputational-based systems to impartial government institutions. But like all mechanisms of cooperation, it is also a means for creating cooperative groups who can compete with one another. Here's how this mechanism of cooperation works.

Religions often use ethnic markers, for example a cross around your neck, a hijab around your face, a vibhuti on your forehead, a pirit string around your wrist, or a yarmulke on your head. These markers allow co-religionists to identify one another. To the degree that the marker is maintained by a community and linked to beliefs, such as being good to others who share your religion, your brothers and sisters in Christ or those in your ummah (community of all Muslims) – for fear of God's punishment or karmic retribution or wish to please Allah – then two individuals sharing those markers may be slightly more likely to trust each other when they meet than they would otherwise. In a world in which hijabs or zebibahs (the calloused, discolored prayer bump Muslims can develop on their foreheads from touching the prayer mat) are rare and indicative of Muslim beliefs, Muslims who don't know each other (direct reciprocity) or even know of each other (indirect reciprocity) may still trust and help each other by recognizing a co-religionist through their hijab, zebibah, facial hair, or clothing style. They do so because they know that those markers indicate a belief that requires them to be good to their co-religionists, norms which are often enforced or encouraged by their community. But remember the ultimate–proximate distinction. Although the world's major religions do share these prosocial beliefs, they didn't have to and indeed many religions over history did not. The question then is how did these beliefs evolve?

Religion may require basic cognitive biases, such as mentalizing, the ability to represent other minds in your mind; teleological thinking, the belief that things happen for a purpose or that there is a reason behind everything; or intuitive mind–body dualism – that the mind and the body are separate. But these biases alone are not sufficient to explain the variety of religious beliefs we see around the world. These cognitive biases are at best proximate building blocks upon which norms can be understood and enforced by the belief in a supernatural punisher. But, of course, different religions have, and have had, different beliefs, ranging from loving enemies to sacrificing children. A clue as to how prosocial beliefs became more common lies in comparing the religious beliefs of societies of different sizes. The gods of small-scale societies are very different to the big gods of the major world religions. The gods of small-scale societies don't want you to cut down the trees or desecrate the water. They are less interested in your sexual habits or whether you're nice to one another. They are limited in the scope of their interests, their power to punish, and their ‘goodness’. In contrast, the gods or supernatural punishing forces of large-scale societies, like the Christian God, Allah, or karma, are all-seeing, all-knowing, powerful in their ability to punish, and all-good, with cooperation paid back in this life or the next.

People often marvel at the commonalities between major world religions – the golden rule, prioritizing family, not lying or cheating, and so on. Major world religions share these beliefs thanks to an evolutionary process that winnowed winning traits helping groups to grow and thrive. Or to put it another way, any major world religion today is a major world religion because it has been able to sustain large amounts of cooperation among co-religionists. Indeed, this has allowed religion to serve as a super-ethnic category, binding people of different ethnic groups that might otherwise be in conflict, for example, the many tribes of Europe under Christianity and the many tribes of Arabia under Islam. As these religions grew, they unified larger numbers of diverse groups. You can be Catholic or Muslim regardless of your ancestry or geographic location. Religion is as much a commitment to a group of people as it is to a set of cultural-group beliefs. Religion supports cooperation, but then, of course, these religious cultural-groups can compete with one another creating higher-scale conflict.

Religion is not unique in creating conflict. Cooperation and conflict occurs through all the mechanisms of cooperation. Families against families, Montagues and Capulets or Hatfield and McCoy; villages against villages; regions against regions; nations against nations; and now large unions – think NATO or the EU – often bound by a common cultural and religious heritage against other large unions bound by another common cultural and religious heritage. But while religions share a lot in common, different beliefs matter, and these are under selection.

A handful of religions now dominate the globe: Christianity (2.3 billion), Islam (1.9 billion), Hinduism (1.2 billion), and Buddhism (500 million). Why do these religions share beliefs in a powerful, good, supernatural punishing power; the importance of obligations, such as to family; and the importance of helping others? From a cultural evolutionary perspective, the reason is simple: any major world religion that has spread to this degree has spread because its features have facilitated that spread.

Being nice to one another and being pro-fertility means stable and often large families that look after each other. These are not beliefs that are universal to all religions that have existed. It's just that some beliefs don't lead to growth and spread and so those beliefs and those religions are no longer with us. They're like the preference for banging your head against a rock.

As one example, you may have Quaker friends but are unlikely to have Shaker friends. Shakers are an offshoot of the Quakers that believed in celibacy for everyone. That's right, no sex, not just for a priestly class, but for everyone. So there are no Shakers left.

These kinds of beliefs don't have to be religious, but they do have to affect action. Setting religion aside for a moment, if the idea of the American Dream leads people to take risks and work harder and there are sufficient resources and energy for these behaviors to pay off, even if only at a country level, then the belief persists because the country can access more energy. The American Dream or America as a ‘shining city on a hill’ need not be true, but only believable enough to lead to behaviors. And if those behaviors lead to a stronger America then they will persist. The same is true of beliefs about equality, freedom, consent, honor, or patriotism.

It takes a group of individuals working together to accomplish both our greatest triumphs and our darkest tragedies. Greater scales of cooperation allow for greater scales of conflict between larger, more cooperative groups. Although we tend to attribute responsibility to individuals (because of our tendency to seek out models to learn from and avoid, as we discussed earlier), no one acts alone.

Vladimir Putin doesn't carry oil in his pockets. His control over Russian resources is contingent on those who benefit from some share of those resources (oligarchs) and in turn the supporters of those oligarchs who get some smaller share, then their supporters, and so on, in a network of political patronage, favors, and financial benefit that stretches even to the politicians and media in other countries. Putin can do this because innovations in efficiency have meant that Russian energy can be controlled and exploited by a smaller cooperative group than was required to access it in the first place. But despite this kind of corruption and even conflict, overall violence has declined.

Long peace?

Is the human heart kind or cruel? Are we fundamentally cooperative or competitive? Are we racist or can we see past our differences?

As both human history and your never-ending newsfeed make clear, the answer to these questions is both. We are capable of great kindness even to those far away. We are capable of great cruelty even to those close to us. We cooperate in groups but those groups compete.

The long arc of human history has seen a decline in cruelty and destructive competition. Blood sports were once mainstream entertainment – gladiators fought each other and large animals for everyone's entertainment in Roman amphitheaters. Today we are entertained by mostly bloodless sports. We used to torture cats for amusement. Today, we are amused by cute cat videos on YouTube.

The centuries and millennia have seen an overall decline in deaths through violence, as Hans Rosling, Steven Pinker, and others have documented in detail. That includes deaths from both homicide and war. Our probability of dying almost anywhere in the world today is lower than it was in centuries past. But that decline has been jagged, punctuated by great evil and periods of intense violence: the two world wars that scarred the twentieth century; the New York crack epidemic in the 1980s and 1990s; the Rwandan genocide of 1994; various Balkan and Middle Eastern conflicts, and more.

There is small solace in reminding people that the arc of history bends toward peace and justice during such times. In telling them that if they were given a choice and had to pick a moment in history to be born without knowing their sex, skin color, sexual orientation, or disabilities, it would probably be around the last few decades. In pointing to statistics or identifying punctuations when, even today, vast inequalities, deep unfairness, and terrible violence still permeate our world, creating much suffering. And there is small solace in reminding us of an overall decline in violence, if we are about to lose a generation to another drawn-out violent world conflict or civil war, or face the economic aftermath of these events.

To continue to make the world a more just, peaceful, and safer place for everyone, we must answer the question of why we see this pattern of an overall decline in violence with large variation over time, geography, and social groups. To know if peace will continue or even expand, we need to know how we became peaceful in the first place.

As we alluded to earlier, various popular answers exist to explain the long peace. Yuval Harari attributes it to the likes of our imagination and intelligence. Steven Pinker attributes it to a variety of factors, such as the rise of states, commerce, Enlightenment values, and the power of reason. But we can imagine many things both peaceful and warlike; we can use our intelligence and reason for both good and evil; the Enlightenment produced many ideas, and the rise of the state itself needs an ultimate explanation. To say that specific ideas produce peace is like saying genes allow for cooperation. Genes are the fodder for genetic selection and ideas are the fodder for cultural selection. The question is why did some ideas spread while others did not?

Take the Enlightenment. German philosopher Immanuel Kant gave us laudable ideas such as ‘Freedom is the alone unoriginated birthright of man, and belongs to him by force of his humanity’, but also deplorable ideas such as ‘Humanity is at its greatest perfection in the race of the whites’. ‘Enlightenment values’ is less an explanation and more an exaltation of values we now possess. It is circular reasoning. The expansion of values we now consider ‘laudable’ and rejection of those we now consider ‘deplorable’ is not an explanation; it is another example of the way in which the world has become more peaceful. We need an ultimate explanation.

The laws of life can create a pattern of an overall decline in violence punctured by small and large conflicts. To demonstrate this process, Eric Schnell, Robin Schimmelpfennig, and I formally modeled co-operation in the context of multiple sources of energy with different EROI requiring different levels of cooperation to unlock and different carrying capacities created by the unlocked energy. We built on a class of cooperation models called the stag hunt.

The stag hunt game captures the dynamics of two people deciding between two scales of cooperation. They can choose to either (1) hunt a hare, which they can do on their own to get a guaranteed energy return of one food unit regardless of what the other person does, or (2) work together to catch a stag with a larger energy return, say six food units: three food units each. The trouble is, it is not certain they will catch the stag. Our ancestors and even present-day hunter-gatherers return from most hunting expeditions with nothing. And so the other person's willingness to cooperate for an uncertain reward rather than go catch their own guaranteed hare is also uncertain. And you can't catch a stag on your own – trying to do so leaves you with nothing. This is the basic stag hunt dilemma. To capture multiple scales of cooperation and a decline in violence, we needed to modify the math.

In the real world, there aren't just stags but also larger animals like buffalo and whales. Not just wood but coal, oil, natural gas, nuclear fission, and fusion. And in the real world it's not just two players but many. In fact, each reward requires a different number of cooperators with different levels of uncertainty depending on the number of cooperators. When you model these complexities, you see exactly what you find in the real world.

Each energy source unlocks a large energy surplus, which creates a larger carrying capacity. Our societies run on this excess energy. This excess energy in turn means more potential cooperators. Larger energy sources require a larger minimum number of people. For any given energy source, the probability of successfully capturing the energy source can increase with more people, but with more people the energy per person decreases. This leads to several interesting dynamics.

First, it's easier to reach a higher scale of cooperation if you are already cooperating at a high scale. An industrialized society can more easily reach nuclear fusion than a pre-industrial agricultural society (even with access to the right technology), and it is easier for an agricultural society to industrialize than a hunter-gatherer society. Consider the ease with which you might put together a team for a project that requires 5 people over one that requires 50 or 500. Doing so from scratch is difficult. For these larger projects or companies, it helps to have an existing large and cooperative group that requires just a few more people – it's easier to expand an existing team.

This model showed an overall decline in violence. With each new, more available, and high EROI source creating a larger space of the possible, violence declined. But what was interesting was that as the carrying capacity exceeded the necessary number of cooperators, smaller scales of cooperation could dominate, creating what we might call corruption. Smaller groups could work together to capture a larger amount of excess energy with a higher energy return per person than a larger group. Moreover, as the number of people grew or the energy ceiling fell, abundance turned to scarcity, leading to conflict between large groups. To put it simply, the presence of sufficient energy leads to an overall increase in cooperation and corresponding decline in violence within these large cooperative groups, such as countries. But this peace is punctuated by violence either from smaller cooperative groups with a higher energy return per person (exacerbated by efficiency innovations that let fewer people capture the same energy) or occasionally between large cooperative groups competing over a larger scarce resource. The decline in violence punctuated by internal conflict and larger-scale conflict are part of the same pattern. But because the punctuations to peace are rare, they would be difficult to detect statistically in the real world, making them look like noise. This explanation is more consistent with everything else we know about our theory of everyone, including the mechanisms of cooperation. Conflicts like the First and Second world wars were not noise. And that means as EROI falls and energy becomes scarce, future internal conflicts and large-scale conflicts are all but inevitable unless we address their underlying cause – energy scarcity and other threats to large-scale cooperation.

To summarize, people cooperate in ever larger groups to access available energy and resources. Within these groups there is more peace, cooperation, and kindness. But between these groups there is often cruelty, exploitation, and destructive violence. Larger groups discover values and norms, such as ideas of equality of all people under the law, stigmatization of discrimination, or valorization of meritocracy, which spread and are enforced through reputation and institutions. These are not self-evident, but in the presence of sufficient resources, they can support higher scales of cooperation. But our cooperation, innovation, and intelligence are a result of these evolutionary forces selecting among possible worlds with different sets of interconnected norms. Successful beliefs persist not through reason, causal understanding, or knowledge, but by their effect on the world and on people's outcomes.

The Great Divergence refers to the way in which the Industrial Revolution catapulted Europe past all pre-industrial empires across the rest of Eurasia and elsewhere. Many other countries have since caught up or are on their way to doing so, using their energy stores and the innovations unlocked during this period in what's called the Great Convergence.

The sudden post-industrial rise in wealth, energy capture, population size, size of countries or polities, child survival rates, human rights, or just about any other indication of progress and social development, as Ian Morris puts it, ‘made mockery of all the drama of the world's earlier history’. That rapid rise is all thanks to fossil fuels, cultural-group selection, and the ways evolution has found to get us to work together, innovate, and become brighter. Yet this astonishing progress may be but a temporary break from harsh Malthusian logic.

All of what we have achieved requires continued access to abundant, dense, high EROI energy sources, without which we start crashing back down. Energy bills rising and discretionary budgets falling; home ownership slipping out of reach; rising prices diminishing our ability to travel, enjoy restaurants with friends, provide for our families, and do all the things that we think of as being part of a good life – are all a result of falling EROI and energy abundance. Our excesses are all dependent on excess energy. As energy abundance turns to scarcity, what we are all feeling in our bones is the beginning of a slow descent before a societal freefall.

Returning to the laws of life

When energy is available, life harnesses it by working together in larger, more complex units and discovering innovative ways to do more with that energy. Geothermal energy and the heat of the Sun with the Moon stirring warmed water full of potential were enough for Earth to evolve simple self-replicating unicellular life. But once simple unicellular life evolved to utilize this energy, a package of stored energy existed that could be exploited. And so multicellular life – single cells cooperating and working together – could evolve to eat these readily available stores of energy. This process continued where plants specialized in harnessing the energy of the Sun, herbivores specialized in eating the stored solar energy in plants, and carnivores specialized in eating the stored energy in herbivores.

For most of human history the energy return was a one-to-one return on our time. As a hunter-gatherer, the amount of food you gathered was a function of how long you spent gathering food. If game was large and easy to find then populations grew to meet this energy ceiling until abundance once again turned to scarcity. In turn, these larger populations with larger collective brains might innovate more efficient hunting, gathering, or food processing to increase excess energy. Two major innovations were fire and cooking. But then once more abundance turns to scarcity. To break out of this requires a larger energy ceiling.

Think of a household budget. You can do a lot more if you work very little for a lot of money. And increasing income always beats reducing expenses. More revenue beats greater efficiency. Only with excess can you go beyond the basics in a household or society. Only with excess can a company grow or conquer new markets. Those with larger budgets can beat those with smaller budgets.

After burning wood and learning to cook, the next major energy innovation was agriculture. It was the first major energy revolution for humans – deliberately and efficiently harnessing the sun's energy for a reliable food source, outcompeting smaller, less energy-rich hunter-gatherers. The reliable food source led to larger populations, which led to scarcity but also to further innovations that allowed for even more efficient use of energy. There was now sufficient surplus food to feed and domesticate animals. So instead of driving the plow by hand, we could drive it with an ox, effectively multiplying the work we could do through the solar energy we captured in the plants we grew and the livestock we looked after.

The next major unlocking of energy was burning the densely stored solar energy of ancient organisms – fossil fuels. This led to the Industrial Revolution, which massively multiplied the amount of work that could be done. Again, our populations grew and so too did our innovative capacity. Instead of driving the plow with an ox, we could use a fossil-fueled tractor. As a result, industrial societies outcompeted non-industrial societies. When energy is available, the processes of innovation lead to more efficient use of that energy, the ability to harness more resources and even to live in places that were previously unlivable (think of cities like Dubai or Phoenix, Arizona).

As with every energy revolution, our populations grew, but the energy of fossil fuels was so abundant it has taken two centuries for abundance to turn into scarcity. That is where we are now.

With the right conditions, our current energy budgets are enough to lead to the next breakthrough in the harnessing and use of energy. But this isn't inevitable. As energy declines, the probability of conflict between large, energy-rich cooperative groups grows. And lower scales of cooperation are always present. These smaller cooperative groups will always try to access more energy per person with fewer people. The cost of corruption and civil unrest are greater when energy is scarce. The threat of international war and civil conflict comes ever closer as the energy ceiling descends.

All complex life is forever in a battle with lower-order cooperation, namely bacteria, viruses, cancers. The COVID-19 pandemic has made this point more obvious than ever. Likewise, all developed societies still deal with lower-order cooperation, such as corruption, cheating, and favoring one's own groups. But the threat from these lower orders depends in part on energy availability.

Organisms and societies become sick when they don't look after themselves; when resources and energy are limited. If you arrive at a parking space and another car unfairly takes it, how will you react? If there's plenty of open spaces, you might graciously carry on. But if everything is full and you've been driving around for thirty minutes, things may be different. The cracks that always existed in a society – the smaller groups based on race, ethnicity, politics, or economic status – may begin to polarize and fracture. The moral circle of who we care about becomes smaller.

It's easier to be nice when there's more to go around.

Expanding Hardin's field

By the laws of life we traverse the space of the possible created by abundant high EROI energy-dense sources. We scramble to do more with less and we transition between scales of cooperation. A good way to think about these dynamics is to return to Garrett Hardin.

Hardin's tragedy of the commons describes a single field of fixed size that can support a fixed number of farmers and their families. We can sustainably manage the field with the mechanisms of cooperation instantiated through principles such as those documented by Nobel Prize winner Elinor Ostrom. That's where most readings of the familiar story stop. But a theory of everyone takes that story further.

If we manage to preserve that first field, and experience bounty and stability, something happens. First, by the law of evolution, if there is excess then we don't just sit on that same field stagnating with our families forever. Rather, some of those farmers may go off and find new fields. Some of those fields may be larger, together supporting a larger number of farmers. Some of those fields may create such an excess of people that it's worth trying to take over the fields of others. In the absence of this between-field competition, a smaller group of farmers may try to take more for themselves and their families at the expense of their village. This process of evolution is an exploration of different beliefs, behaviors, norms, and social organizations, between and within fields, increasing through innovation, cooperation selected through competition.

With enough fields, enough farmers, and a surplus of food, some of those farmers’ children can now spend their time doing things other than farming. Some might figure out ways to drive a plow with a domesticated ox or eventually a fueled tractor. These innovations can more efficiently farm the fields, even expanding the fields or making them greener. Innovations that increase efficiency – by unlocking energy – mean better food returns on the number of hours spent farming, requiring fewer farmers to feed a larger village.

More people and more energy mean more people to refine other processes and develop other skills and knowledge – not only in science and engineering but also in art, literature, and entertainment – which lead to more opportunities for new ideas that lead to breakthroughs that are – inevitably – about energy and the control over it.

This pattern of growth and expansion, abundance and scarcity, driven by innovations in efficiency and greater energy control – originating in our sensibility to not burn through a single field we share – is at the heart of the human journey.

These patterns embodied in a theory of everyone and the laws of life are lenses through which to understand our genetic and cultural inheritances, to grasp the manner in which we work together to learn and to know and to innovate, to appreciate where we have been as a species, and glimpse where we are headed. Because by looking ahead, we can better steer our ship.

In the second part of this book we'll discover where we're going. Where we need to go is the next level of energy abundance. To get there, we need to solve several puzzles. For example, one puzzle that plagues economics is why, despite large innovations in computing and the Internet, production has increased but productivity – the rate of production – has been slow to increase. As economist Robert Solow put it, ‘You can see the computer age everywhere but in the productivity statistics.’ Part of the answer is that the Internet and computation is less like the Industrial Revolution and more like the Enlightenment that preceded it.

The Enlightenment was the launch platform, if you will; the apparatus and even the initial burn that then quite literally shot the human rocket into space. The knowledge it unlocked eventually led to physical innovations in the control of the energy-dense fossil fuels that wildly accelerated what humans could do. We are still living off the back of that revolution, which truly increased not just production but productivity.

There are barriers that block us from reaching this next level. How do we get past them? How do we reunite humanity, develop government institutions for the twenty-first century, create a fairer world, trigger a creative explosion, and maximize the potential of all people? And, by corollary, how do we overcome the forces pushing us in the opposite direction – tearing us apart, disenfranchising communities, increasing inequality, slowing innovation, and wasting human potential?