Willard Inter-Continental

Willard Inter-ContinentalThe Willard isn’t what comes to mind when someone says historic inn. The grande dame of Washington now is a luxury hotel offering guests every amenity, but at heart she is one of the great historic inns, albeit one that is twelve stories high and has grown and prospered with the times.

Abraham Lincoln, his family, and several aides stayed here before his inaugural, and his bill for $773.75 is on display in the lobby today. Indeed, every president from Franklin Pierce to Bill Clinton has stayed here on the eve of his nomination. Throughout the war, the Willard was the center for Union generals (Grant stayed here four times) and politicians; in fact, the word “lobbyist” was coined to describe the office-seekers who hung around the Willard lobby hoping to buttonhole influential politicians. Julia Ward Howe was a guest here when she wrote the words to “Battle Hymn of the Republic.”

While covering the war for The Atlantic Monthly, Nathaniel Hawthorne described the Willard: “This hotel, in fact, may be much more justly called the center of Washington and the Union than either the Capitol, the White House or the State Department … you exchange nods with governors of sovereign states; you elbow illustrious men, and tread on the toes of generals; you hear statesmen and orators speaking in their familiar tones. You are mixed up with office seekers, wire pullers, inventors, artists, poets, prosers … until identity is lost among them.”

Address: 1401 Pennsylvania Ave. NW, 20004, two blocks east of the White House; tel: 202-628-9100; fax: 202-637-7326.

Accommodations: 340 first-class rooms, including thirty-eight suites.

Amenities: All rooms are furnished in Queen Anne style. Oversized bathroom with a phone, hair dryer, and television speaker. Concierge. Restaurants include the elegant Willard Room. Shop ping. Exercise room. Famous Peacock Alley runs the length of the hotel, connecting Pennsylvania Avenue and F Street.

Rates: $$$. All credit cards accepted.

Restrictions: Some restrictions on pets.

Morrison-Clark Inn

Morrison-Clark InnIn 1864 two of Washington’s leading families built homes side by side, just northwest of fashionable Massachusetts Avenue, near Mount Vernon Square. Today, these Victorian houses are the heart of a distinctive historic inn. Daniel L. Morrison made a fortune selling flour and feed to the government during the war; Reuben B. Clark, Washington’s jail commissioner, became wealthy through land investments. The Morrison house was purchased in 1923 by the Women’s Army and Navy League and converted into an inexpensive place for enlisted men to stay while visiting Washington. Later the facility was expanded to include the Clark home. Traditionally, first ladies presided over the club. When it opened in 1923, Grace Coolidge headed the receiving line.

In 1987 the property became the Morrison-Clark Inn after being renovated by William Adair, who supervised the renovation of the White House. He preserved the historic exterior and many of the interior details, including four pier mirrors and Carrara marble fireplaces. Many of the guest rooms contain historic features, and are decorated with period furnishings and original art. The handsome Morrison-Clark Restaurant, one of the finest in the capital area, was cited by Gourmet magazine in 1997 as one of “our readers’ top tables.”

The Morrison-Clark house magically transports guests back in time to a luxurious mansion in Lincoln’s Washington.

Address: Massachusetts Ave. and 11th St., NW, Washington, DC 20001; tel: 202-898-1200 or 800-332-7898 (reservations); fax: 202-289-8576.

Accommodations: Fifty-four rooms and suites.

Amenities: Gourmet restaurant (202-289-8580), period furnishings, minibar, hair dryer, voice-mail, twice-daily maid service and nightly turndown, complimentary newspaper, fitness center, parking garage under building.

Rates: $$-$$$. All credit cards and personal checks.

Restrictions: No pets.

Ford’s Theatre and

Ford’s Theatre and

On the evening of April 14, 1865, John Wilkes Booth, a well-known actor and Southern sympathizer, slipped into the presidential box at Ford’s Theatre and shot President Abraham Lincoln in the back of the head. Lincoln, unconscious, was carried across the street and placed on a bed in the Petersen house, where he died the next morning.

Leaping from the box to the stage, Booth broke his leg but managed to hobble out of the theater, mount his horse, and flee the city. Booth was shot to death in a barn at Port Royal, Virginia, on April 26.

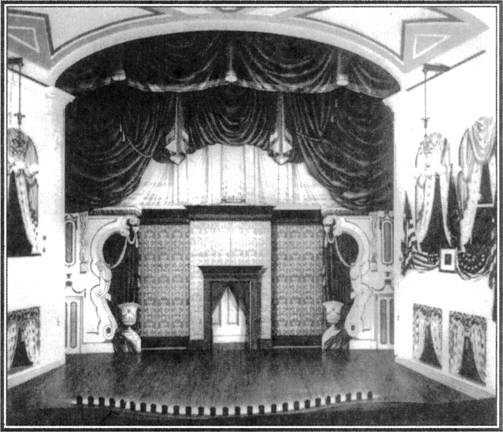

The theater was purchased by the government shortly after the assassination. It was first used as offices and later as the Army Medical Museum. It was restored in the 1960s. Box 7, where Lincoln was shot, has reproductions of the original furniture, including the president’s rocking chair, in which he sat on the fateful night.

The Petersen house belonged to a German immigrant, William Petersen, a tailor who ran it as a boardinghouse. The ground-floor bedroom where Lincoln died has been restored along with the front parlor where Mrs. Lincoln waited through the night, and the back parlor where Secretary of War Edwin Stanton interviewed witnesses to the shooting. The government purchased the house in 1896.

Ford’s Theatre and the Petersen House National Historic Site, 511 and 516 10th St., NW, Washington DC 20002, are open daily, 9:00-5:00, except Christmas. A museum in the theater contains the murder weapon, the flag that covered Lincoln’s coffin, the clothing he wore the night he was shot, and other memorabilia connected with the assassination. For information phone 202-426-6924.

In Maryland, some fifteen miles south of Washington on U.S. 31, are two sites connected with Booth’s flight from Washington.

Surratt House and Tavern, 9118 Brandywine Rd., Clinton, MD 20735 (once named Surrattsville). John Surratt, one of John Wilkes Booth’s co-conspirators, hid weapons in this tavern and post office operated by his mother, Mary. Althoug she allegedly had no knowledge of the murder plot, a military court found her guilty of aiding the conspirators, and she was hanged. The jury failed to agree on the guilt of her son, and the charges against him were dropped. Booth stopped here briefly on his flight from Washington, to retrieve a weapon he had hidden here. Open March through December 11, Thursday-Friday, 11:00-3:00, and Saturday-Sunday, 12:00-4:00. Admission is $1.50 for adults, $1 for seniors, and $.50 for children five to eighteen. For information phone 301-868-1121.

Dr. Samuel A. Mudd Home and Museum, just off Poplar Hill Rd. in Waldorf, MD, is the home and plantation of the doctor who set Booth’s leg. Dr. Mudd was sent to Fort Jefferson Prison on Dry Tortugas Island, Florida, but was pardoned by President Andrew Johnson in 1869. Open April through November, Wednesday, 11:00-3:00, and Saturday-Sunday, 12:00-4:00. For information phone 301-645-6870.