Bennett Place

Bennett Place

Two old battle-weary adversaries, Joseph E.Johnston and William T. Sherman, met under a flag of truce midway between their lines on the Hillsborough Road, seven miles from Durham Station. Needing a place to confer, Johnston suggested a simple farmhouse a short distance away, the home of James and Nancy Bennett. The generals would meet here three times, struggling to achieve equitable terms of surrender. On April 26, 1865, the farmhouse became the site of the largest troop surrender of the war.

Striving to avoid capture in Virginia, President Jefferson Davis arrived in Greensboro, North Carolina, on April 11 and summoned Johnston to assess the strength of his army. Davis believed the South could and should continue the war, but the news of Lee’s surrender prompted him to allow Johnston to confer with Sherman.

At their first meeting, Sherman showed Johnston a telegram announcing the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Sherman explained that he was prepared to offer terms similar to those Grant gave Lee. Johnston demurred, saying he wanted “to arrange the terms of a permanent peace,” political as well as military.

At the second meeting, on April 18, now knowing that Johnston’s surrender wasn’t a military necessity, Sherman gave Johnston a “memorandum or a basis of agreement.” Johnston accepted the terms. This liberal document provided for an armistice that could be terminated on forty-eight hours’ notice, and its provisions included the disbanding of Confederate armies following the deposit of arms in state arsenals, recognition of state government, establishment of federal courts, restoration of political and civil rights, and the promise of a general amnesty.

Davis, unhappy with the terms, ordered Johnston to disband his infantry and make an escape with the cavalry. Johnston, realizing the devastation a prolonged war would bring, disobeyed his president. He met with Sherman again at the farmhouse on April 26.

As it turned out, the final agreement was simply a military surrender ending the war in the Carolinas, Georgia, and Florida, affecting 89,270 Confederate soldiers. The mustering out of Johnston’s troops and the issuing of pardons took place in nearby Greensboro.

Two more surrenders would follow. Richard Taylor surrendered his army in Alabama on May 4, and E. Kirby Smith surrendered his at Galveston on June 2. This meant that Confederate forces now were completely disbanded.

Bennett Place State Historic Site, 4409 Bennett Memorial Rd., Durham, NC 27705, is six miles west of Durham, then a half-mile south of I-85 on U.S. 70. From I-85 north, take Exit 170 onto U.S. 70, then, after approximately a half mile, turn right onto Bennett Memorial Rd. The site is a half mile farther on the right. From I-85 south, take Exit 173 and follow the signs.

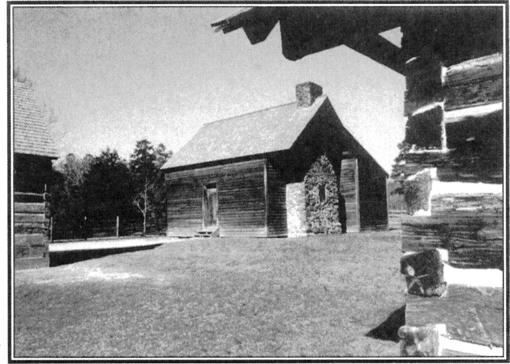

The original buildings, destroyed by fire in 1921, have been reconstructed from wartime photographs and sketches. An audiovisual program tells of the Bennett family and the events that happened here.

Open April through October, daily, 9:00-5:00; November through March, daily except Monday, 10:00-4:00. Closed Thanksgiving and December 14-26. The surrender is reenacted the first Sunday in December. Admission is free. For information phone 919-383-4345.

Bentonville Battleground

Bentonville BattlegroundIt was the Confederacy’s last chance to prevent General William Tecumseh Sherman’s army, marching north from Georgia, from linking up with Grant, who had Lee’s army pinned down at Petersburg. As Sherman’s army entered North Carolina, hundreds of North Carolinians deserted Lee’s army to protect their homesteads. General Joseph E. Johnston’s small force had attempted to stem the tide at Aversboro on March 16, 1865, but the big battle, the biggest ever fought in the state, was here, three miles east of Newton Grove, on March 19, 20, and 21. It was the last battle in which a Confederate army was able to mount even a minor offensive.

With fewer than thirty thousand men, Johnston waited until miserable road conditions forced Sherman, who was headed for Goldsboro, to divide his sixty-thousand-man command into two wings. Discovering that the Union wings had become separated by a half-day’s march, Johnston saw an opportunity to destroy first one wing, then the other. On the evening of March 18, Johnston organized his forces into a sickle-shaped line along the Goldsboro Road near the village of Bentonville and waited. Sherman’s left wing stumbled into the trap. Initial attacks overran large sections of the Union lines. But one division managed to hold on, despite being attacked on both sides, and it saved the day. Failing to crush the Union lines, Johnston pulled back to his original position.

Sherman’s right wing arrived at the battlefield early the next morning, and for two days cannon and rifle fire were constant. On March 21 a force led by General Joseph A. Mower outflanked the Confederate positions, coming within two hundred yards of Johnston’s headquarters before falling back. That evening the weary Confederates abandoned their positions and withdrew north to Smithfield. Sherman marched to Goldsboro, where supplies awaited him. More than four thousand Union and Confederate troops were killed, wounded, or missing during the battle at Bentonville, fought in an area of six thousand acres.

The restored Harper House was used as a hospital for the wounded of both sides. On the battlefield are original and reconstructed trenches. An audiovisual show at the Visitor Center explains the battle and its significance. The history trail has markers and exhibits, and the roads in the area are marked with plaques highlighting events of the battle.

Bentonville Battleground State Historic Site is fifteen miles east of Dunn. From I-95, take Exit 90, drive fifteen miles south on U.S. 701; turn left onto Rte. 1008, then drive three miles east to the site. Besides the Harper House and the trenches, there is a Confederate cemetery and a history trail with exhibits. Open April through October, daily, 9:00-5:00, Sunday 1:00-5:00; daily except Monday, 10:00-4:00, and Sunday, 1:00-4:00, the rest of the year. Closed Thanksgiving and December 24-26. Admission is free. For information phone 910-594-0789.

Some forty miles north in Durham is the Bennett Place State Historic Site, where, in April, Johnston surrendered his army to Sherman.

Arrowhead Inn

Arrowhead InnThis inn predates the Civil War; actually, it predates the Revolutionary War. The “Old House,” as it was once called, was built between 1774 and 1780 by the Lipscomb family, who owned a two-thousand-acre plantation in the North Carolina Colony. It was on the “Great Path” over which Catawba and Waxhaw Indians traveled between Virginia and the mountains. Yankee soldiers also came this way during the war: a “boot” derringer of the type carried by many Union soldiers was unearthed on the premises recently. The Southern colonial manor house was lovingly restored before it became an inn in 1985. The guest rooms are all decorated in a tasteful interpretation of the Civil War period. A family (or a honeymoon couple) would enjoy the Land Grant Cabin. It has a sitting room with wood-burning fireplace, a sleeping loft, and a large bath.

The Arrowhead Inn feels as if it were blessedly far from everything, but it is only minutes away from Durham and the Bennett Place, where Johnston surrendered to Sherman. Stroll the four-acre grounds under 150-year-old magnolias; some thirty-three varieties of birds have been seen here. One of the innkeepers—Jerry, Barbara, or Cathy Ryan—is always on the premises to give directions or solve problems.

Address: 106 Mason Rd., Durham, NC 27712; tel: 919-477-8430 or 800-528-2207; fax: 919-471-9538.

Accommodations: Eight double rooms, all with private baths and phones.

Amenities: Gardens, birdwatching.

Rates: $$$. All major credit cards and personal checks.

Restrictions: No pets, but boarding kennel nearby; restricted smoking.

Miss Betty’s Bed and

Miss Betty’s Bed andAn 1858 house, an Italianate “Painted Lady,” is the headquarters of this charming inn complex in the historic district of Wilson. The inn includes two historic houses, the Davis-Whitehead-Harris House and the adjacent Riley House.

The inn is on Nash Street, once described as one of the ten most beautiful streets in the country. Innkeepers Betty and Fred Spitz have given the inn period furnishings, and many of the antiques on display are museum quality (Betty is an antique dealer, and Wilson is considered the antique capital of the state).

The town’s Maplewood Cemetery is the resting place of the Betsy Ross of the Confederacy, Rebecca M. Winbonne, who reportedly made the original Stars and Bars. Wilson is within easy driving distance of the Bentonville Battlefield in Newton Grove and the CSS Neuse State Historic Site in Kinston.

Address: 600 W. Nash St., Wilson, NC 27893; tel: 919-243-4447 or 800-258-2058.

Accommodations: Fourteen double rooms, all with private baths.

Amenities: Air-conditioning, off-street parking, fireplaces; phones and TVs in guest rooms, golf and tennis nearby.

Rates: $ single; $$ double, including full breakfast. All major credit cards and personal checks.

Restrictions: No children under thirteen, no pets, no smoking.

The Cedars Inn

The Cedars InnThis town (pronounced Bow-furt, unlike its South Carolina namesake Bew-furt) was settled in 1709, and is one of the oldest towns in the state. Federal forces occupied Beaufort in March 1862, and for the duration of the war it served as an important base of operations for the Union offensive in the South. The huge Federal fleet that delivered the death blow to the Confederacy in January 1865 assembled here.

Today Beaufort is a charming fishing village, and the houses in the historic district show the influence of trade with the West Indies. The Cedars, built about 1768, has been beautifully restored by innkeepers Sam and Linda Dark. They purchased the matching house next door, enabling them to double the number of guest rooms, and added a restaurant that is the best in town. The inn is on the waterfront in the historic district, a short walk from the interesting maritime museum and the other attractions of the town.

Address: 305 Front St., Beaufort, NC 28516; tel: 919-728-7036; fax: 919-728-1685.

Accommodations: Eleven double rooms, all with private baths.

Amenities: Air-conditioning, off-street parking, ferry service to

offshore islands, bicycling, full breakfast in dining room.

Rates: $$-$$$. American Express, Visa, MasterCard, Discover, and personal checks.

Restrictions: No children under ten, no pets, restricted smoking.

Fort Macon

Fort Macon

Designed by General Simon Bernard, a French military engineer, to protect the Beaufort Inlet, Fort Macon was one of a chain of forts built along the Atlantic Coast after the War of 1812. Not long after it was garrisoned in 1834, it developed a problem with erosion. The army sent a young engineer to remedy the problem—Captain Robert E. Lee. The system of stone jetties he designed can be seen today.

Captured by the Confederates in 1861, it was recaptured a year later by a Union sea and land assault commanded by John G. Parke and Ambrose Burnside. After eleven hours of bombardment, commander Moses J. White surrendered the fort. Shells from Federal batteries firing rifled cannon had penetrated rooms near the powder magazine, creating the danger of a lethal explosion.

For the duration of the war, Fort Macon was under Union control. It was used as a prison and a coaling station. The fort remained active until after World War II. An unusual accident occurred here in 1942. Soldiers found that the quarters in the fort were heated only by fireplaces. Civil War shells being used as andirons exploded, killing two soldiers and wounding several others.

Fort Macon is one of the best-preserved forts in the country. The outer and inner walls are separated by a deep, twenty-five-foot-wide moat. The outer walls are more than twenty feet thick, and allow magnificent views of the Beaufort Inlet. Twenty-six casements (vaulted rooms) are situated around the parade grounds, and some have been restored to represent the quarters of officers and men.

Fort Macon State Park is reached from I-40 or I-95. Take Rte. 70 east to Morehead City, turn onto the Atlantic Beach Bridge and follow right to the intersection with Rte. 58, turn left onto 58, and the park is at the end of the road. Open daily, 9:00-5:30. Closed Christmas. Museum in casement. Guided tours daily from Memorial Day to Labor Day. Civil War reenactments are held on the parade grounds on three summer weekends. West of the fort a park road leads to picnic grounds, a bathhouse and pavilion, and a public beach. Admission to fort and beach is free. For information phone 919-726-3775.

Harmony House Inn

Harmony House InnWhen you enter this handsome inn in the historic district, you will see framed prints from Harper’s Weekly that depict the Battle of New Bern. The town fell to Union forces in March 1862, and served as their base of operations in eastern North Carolina for the rest of the war. This house was occupied by Company K of the Forty-fifth Massachusetts Regiment. A photograph of soldiers posing in front of the house may be seen in the inn.

Ed and Sooki Kirkpatrick bought Harmony House in 1994 and have refurbished the interior. Canopy beds and comforters grace the bedrooms, two new suites have been added, one with a heart-shaped Jacuzzi, and guests will enjoy the homemade decorations crafted by Sooki. The inn is on the National Register of Historic Places. The Civil War Museum, just down Pollock Street from the inn, displays one of the finest and most comprehensive private collections of Civil War firearms and accoutrements in the country. The museum, which is closed in the winter, will direct you to the houses in town that played a role in the war, although most are now private homes.

Address: 215 Pollock St., New Bern, NC 28560; tel: 919-636-3810 or 800-636-3113; E-mail: harmony@nternet.net.

Accommodations: Eight double rooms and two suites, all with private baths and phones.

Amenities: Air-conditioning, off-street parking, TV in rooms.

Rates: $$-$$$. Visa, MasterCard, Discover, and personal checks.

Restrictions: No pets, no smoking.

CSS NEUSE

CSS NEUSEAfter Federal troops occupied New Bern, the Confederate navy decided to build an ironclad gunboat on the Neuse River, take it downstream, and recapture the city. Pine forests would provide the lumber, and the shipwrights would be the local carpenters. Construction began in the fall of 1862, but was interrupted by a Federal raid in the area. The hull of the twin-screw ironclad steamer measured 158 feet long and 34 feet wide, and resembled a flat-bottomed river barge. Commissioned the CSS Neuse, it was launched in 1863 and floated down the river to Kinston, where it was to be fitted with machinery, guns, and iron armor plating. Problems delayed completion, and, in fact, the Neuse never did receive all its armor.

While steaming to New Bern it ran aground, and when the river rose it returned to Kinston, where it sat idle for ten months. As Federal troops approached in March 1865, Commander Joseph Price ordered the vessel scuttled in the river to avoid capture. While the Neuse never saw battle, its presence was an important factor in preventing Union forces from moving from New Bern to Goldsboro. The Neuse remained at the bottom of the river for nearly a century. It was raised in 1963 and moved here a year later. It’s one of only three Civil War ironclads extant.

The CSS Neuse State Historic Site is near the city limits of Kinston. From I-95 take the Smithfield/Selma, NC, exit, then U.S. 70A east about forty-five miles to Kinston, then U.S. 70A to site. The wooden skeleton of the ironclad is on display. In the Visitor Center, an audiovisual presentation tells the story of the Neuse and has related exhibits and demonstrations of nautical blacksmithing. Historic photographs and artifacts are on display. Open April through October, daily, 9:00-5:00, Sunday 1:00-5:00; daily except Monday, 10:00-4:00, Sunday, 1:00-4:00, the rest of the year. Closed Thanksgiving, December 24-26, and other major state holidays. Admission is free. For information phone 919-522-2091.

Orton Plantation

Orton Plantation

This magnificent mansion overlooking Cape Fear was built around 1730 and became the center of a large rice plantation. During the Civil War, Orton was used as a military hospital and was not destroyed, as many of the houses in the area were. The war left the owner, Thomas Miller, bankrupt, and the estate was abandoned until the 1880s, when it was bought and restored by former Confederate colonel Kenneth M. Murchinson.

Today the Orton Plantation is well known for its beautiful gardens with live oaks, magnolias, and ornamental plants. The old rice fields are now a wildlife refuge. In the spring, when the azaleas are in bloom, visitors come from all over the world.

Orton Plantation Gardens, eighteen miles south of Wilmington on NC 133. Grounds open March through November, daily except some holidays (mansion not open to public), 10:00-5:00. Admission is $8 for adults, $7 for seniors, and $3 for children two to twelve. For information phone 910-371-6851.

Fort Fisher

Fort Fisher

By the last year of the war, Fort Fisher was a bone in the Union’s throat. The huge earthwork fort at the mouth of the Cape Fear River kept the port of Wilmington open, allowing blockade runners to bring supplies for Lee’s beleaguered army. Lee warned: “If Fort Fisher falls, I will have to evacuate Richmond.”

The fort’s forty-seven big guns threatened Federal warships trying to enforce the blockade, and its earth and sand mound construction readily absorbed shot and shell. Perched on a bluff, the fort was manned by two thousand troops.

In December 1864 Union warships bombarded Fort Fisher for two days without success. During a second attack, in January 1865, gunboats pounded the fort as Union troops stormed across the beach under intense fire, suffering heavy casualties. A large Union force, attacking from another side, found that the bombardment had blown a hole in the wall, entered, and captured the fort in bitter fighting.

The remaining forts in the Cape Fear area were evacuated, and when Union troops entered Wilmington, Lee’s supply line was severed. The fall of the Confederacy was only a few months away.

The L-shaped fort was massive; the wall facing the sea was more than a mile long, the land wall a third of that. The earthwork walls rose twenty feet above the sea. To cushion the fort from naval gunfire, the walls were twenty-five feet thick.

Today erosion is slowly destroying Fort Fisher. All that is left are contoured mounds. In the small museum at the Visitor Center is a model of the fort in its glory years. Also on display are a reconstructed gun emplacement and items recovered from sunken blockade runners. An audiovisual program tells the story of the fort. An interpretive program is given in the summer, and a commemorative anniversary program is held at the fort in January.

Fort Fisher State Historic Site is open April through October, daily, and daily except Monday from November through March. Closed Thanksgiving and December 24-25. Admission is free. From Wilmington, take U.S. 421 south approximately twenty miles to Kure Beach. Fort Fisher is four miles past Kure Beach. A car ferry links the fort and Southport, a favorite of yachtsmen traveling the Intercoastal Waterway. The ride takes about thirty minutes. For information phone 910-458-5538.

Go fourteen miles north of Southport on NC 133, then follow signs from the highway to Brunswick Town-Fort Anderson State Historic Site, 8884 St. Philips Rd. SE, Winnabow, NC 28479. The town was built by colonists during the 1720s. Across part of the site are the Civil War earthworks of Fort Anderson. The Visitor Center has exhibits and an audiovisual presentation. A Civil War encampment is held here in mid-February. Open April through October, daily; November through March, daily except Monday. For information phone 910-371-6613.