CHAPTER TWO

Ferus Gallery

Before Ferus, art galleries owned by Felix Landau, Earl Stendahl, Dalzell Hatfield, Frank Perls, Paul Kantor, David Stuart, and others imported Impressionists, Cubists, Surrealists, and New York School Abstract Expressionists and occasionally showed some L.A. artists with modern leanings. However, this awareness and practice of modern art did not constitute much in the way of a scene. The city’s distinctive Modernist enterprise in art, as in architecture and design, attracted spirited individualists. Hopps explained, “Although a quasi-official Los Angeles avant-garde, centered around the post-Cubist painter Rico Lebrun, was visible throughout the city, alternative modern art could be seen in only a few experimental movie houses or the walls of bohemian cafés.”1

Ferus, founded in 1957 by Hopps and artist Ed Kienholz, represented a group of Los Angeles artists who were friends—who hung out and supported one another in their attempt to create something that departed from the immediate past and embraced the aesthetics of the sixties. Their synergy with one another and with musicians, actors, photographers, fashion designers, and architects would eventually transform Los Angeles. Robert Irwin later said, “The idea of a career wasn’t an issue for any of us because if it had been we would’ve left and gone to New York like all the generations before us, because that’s where careers were made. The reason that generation of artists is so seminal to L.A. is because it was the first one that didn’t leave and made a commitment to stay in L.A.”2

The Ferus Gallery gang: John Altoon, Craig Kauffman, Allen Lynch, Ed Kienholz, Ed Moses, Robert Irwin, and Billy Al Bengston, Los Angeles, 1958

Photograph by Patricia Faure, © The Estate of Patricia Faure

Virtually all of the artists who showed at Ferus in the early years were enamored of Abstract Expressionist artists Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Mark Rothko, Franz Kline, and others. These artists had toiled in poverty and obscurity for decades before finding support from patron Peggy Guggenheim or critics Clement Greenberg and Harold Rosenberg. The Ferus founders and artists admired the stubborn determination of the New York painters to make something original and authentic. For a few years, most of them emulated that gestural abstract style of painting, though it was difficult for them to accept the New Yorkers’ soul-searching angst. Also, on the West Coast, they were slightly behind the curve in their understanding of such painting, which they knew initially from black-and-white reproductions in magazines such as ARTNews and Studio International.

In 1956, Pollock killed himself in a car crash. Within two years, his paintings and those of the other Abstract Expressionists started selling for large sums, and the outsiders were suddenly insiders. The Abstract Expressionists were practically establishment in the opinion of young Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg, who challenged virtually all of the ideas Rothko, De Kooning, and company held dear. Hopps and Kienholz, neither of whom had been to New York at that point, were not yet aware of such shifts and proudly showed gestural abstract painting from Northern and Southern California. For conservative Los Angeles during the Eisenhower years, such work was viewed as pretty radical.3

They were quite the odd couple: The square-jawed, sandy-haired Hopps was so often outfitted in a suit and tie, sporting black, square-rimmed glasses, that his friends used to tease him about being in the CIA. In contrast, Kienholz was a cherubic farm boy and aspiring Beat with a receding hairline, a goatee, and an expanding belly. Both were autodidacts who were seemingly incapable of getting along individually in the conventional world. Together, they had a chance. “We couldn’t have been more different sorts of people,” Hopps said, “but it was clear to both of us that we had an agenda to further the kind of art that interested us in our own ways.”4

Hopps insisted that the name of the gallery derived from Ferus hominus, which he believed to be an anthropological term for pre–Homo sapiens man. “They were described as being very hardy, irascible, dangerous beings and I thought that was an apt description of the artists I was involved with,” he explained.5

On another occasion, Hopps said the gallery was named in honor of James Ferus, a talented teenager at Eagle Rock High School, Hopps’s alma mater, who had committed suicide. “It was two edged, something very involved about what we felt was living art and how it would be named after someone who was no longer alive.”6

Walter Hopps

Photograph courtesy of Nancy Reddin Kienholz

Irving Blum insisted later that it meant “for us,” a gallery conceived as a support system for artists. In name as in all else, Ferus was many things to many people, and it gained a mythic reputation.

Walter Wain Hopps III, born in 1933, was a fourth-generation Californian raised in comfortable Eagle Rock, a small city to the west of Pasadena. His father was an orthopedic surgeon and his mother trained in Jungian psychology, though she never practiced. Hopps was adept at math and science, and his parents expected him to become a doctor. They suggested Yale, but the lure of jazz clubs and modern art led him to choose Stanford University near progressive San Francisco. With his open-faced friend James Newman, he formed a venture called Concert Hall Workshop that booked jazz gigs at colleges. (Since the age of sixteen, using fake driving licenses, Hopps and Craig Kauffman had seen Charlie Parker, Miles Davis, and other jazz musicians performing at the clubs along Central Avenue in Los Angeles as well as in San Francisco.)

After contributing a bawdy submission to a campus magazine, Hopps fell afoul of Stanford authorities. He transferred to the University of California–Los Angeles in 1951. Though he took the appropriate courses for medical school to please his parents, he was consumed by curiosity about modern art and its history.

His inability to conform continued after he was called up to serve in the army in February 1953. At Fort Ord, on Monterrey Bay in Northern California, his attitude was so defiant that he was made to repeat the basic training course until he came close to a nervous breakdown, which later led to his release.

One of Hopps’s first and most telling curatorial events was the 1955 Action I, taken from art critic Harold Rosenberg’s term “Action Painting.” He was still in boot camp at Fort Ord when he came up with the idea. After he was released from the army, Hopps, Kauffman, and painter Ed Moses drove a car with a trailer up to San Francisco to collect large abstract paintings by Clyfford Still, Richard Diebenkorn, and others. Hopps had zero credentials but unbeatable patter. The artists trusted him completely and lent their work to this unprecedented event. As they sped along a winding road in the San Fernando Valley, the car swerved and the trailer broke loose, veering across the street and tearing up some lawns before staggering to a halt. Against all odds, the good fortune of the enthusiastic amateurs prevailed. After righting the trailer, they managed to get to Santa Monica with the paintings and themselves undamaged. Together, they hung the paintings on a sheet of canvas that they had stretched around the perimeter of a merry-go-round on the pier. The exhibition revolved slowly to the sounds of the calliope, jazz records, and John Cage’s score for twelve radios to a vanguard audience of artists, Beat poets Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac, and bewildered passersby.

Hopps’s parents were not supportive of these extracurricular art endeavors so he was obliged to work part-time as a university janitor and as an orderly in the psychiatric ward of the university hospital. Around this time, he became involved with a lithe and lovely blonde, Shirley Neilsen, whose parents were doctors and friends with Hopps’s parents. The young couple had known each other since childhood.

While Hopps went to UCLA and staged art events, Shirley doggedly completed her undergraduate degree in art history at UCLA and her master’s degree in art history at the University of Chicago, specializing in art of the Northern European Renaissance and modern eras. Hopps audited one of Shirley’s courses in art history, but he never completed a degree, though he concealed this fact. “Walter appropriated my education,” Shirley said dryly.7 He told people that he’d attended the same schools as Shirley, implying that he had the same qualifications. “He was so brilliant, he should have advertised the fact that he hadn’t even taken classes,” she said.8

Shirley and Walter Hopps after their wedding, December 1956

Photograph by Edmund Teske, courtesy of Shirley Blum

In 1955, Walter and Shirley were married at Watts Towers, the soaring concrete sculptures covered in shards of glass and ceramics that the Italian immigrant laborer Sebato “Simon” Rodia had devoted most of his life to completing. Hopps’s parents did not attend. Pictures of the ceremony were taken by the experimental photographer Edmund Teske, who later shot an album cover for the Doors.9

Hopps sold his stamp collection and some war bonds to open his first gallery, Syndell Studio, in a storefront he rented for seventy-five dollars a month in a building made of concrete and telephone poles at 11756 Gorham Avenue in Brentwood. The newly married couple moved into a small apartment in the back. Syndell was the name of a farmer who had died by running across the highway in front of a car driven by Hopps’s Stanford classmate James Newman. A suicide. No charges were filed against Newman, but it was so upsetting to him that he suggested the gallery be named in Syndell’s memory; Newman soon took up residence to help run the place. Hopps and his friends made and exhibited artworks under the guise of a fictional artist, Maurice Syndell.

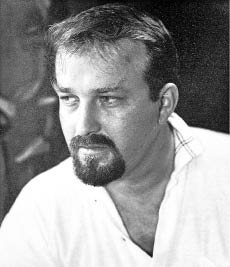

Ed Kienholz

Photograph courtesy of Lyn Kienholz

Artists Ben and Betty Bartosh helped, as did Shirley when she wasn’t taking or teaching courses in art history. Open by appointment, the gallery showed abstract paintings by Hopps’s friends Kauffman, Kienholz, and others to an unappreciative audience. Shirley said, “The people who came in were essentially hostile.”10

In 1956, Kienholz invited Hopps to stage a second show of abstract painting, Action2, at his Now Gallery in a theater on North La Cienega Boulevard. A small room with the gallery name posted in letters made of rough sheet metal, it attracted Beat artists Wallace Berman, Robert Alexander, and George Herms and hipster actors Dennis Hopper and Dean Stockwell. (A few years later, in 1966, Stockwell and Herms would collaborate on the art film Moonstone.)

It had been quite the winding career path for Kienholz. Born in 1927, he spent the first seventeen years of his life on a 350-acre wheat farm eight miles from Fairfield, Idaho, where he learned from his father how to build fences, milk cows, and repair cars, as well as other practical farming skills. At the rural high school he attended, his burly build was a natural for the football team, where he played center. He also designed sets for small plays, sang in the choir, played French horn in the band, and excelled in shop and art classes—but flunked math. He could not reveal his enjoyment of drawing and painting, which, in his words, “were considered feminine.” There were no museums in the area. “A picture to me would be an engraving of George Washington hanging above the blackboard in school,” he said. “From my childhood, I mostly remember isolation, being separate and apart.… I used to sit in the barn and milk the cows and look out through the barn doors and see the aura of the lights above Spokane, which was some forty miles distant, and know that people were not milking cows in Spokane.”11

Hard bargaining was his method of survival. He refused to become a farmer and left home at age seventeen after a fight with his father. For several years, he moved so frequently that he managed to avoid being drafted for the Korean War. He worked odd jobs: proprietor of a rural hamburger stand in Washington, helper in a Spokane bar, foreign car salesman and painter in a sign shop in Reno. (After a drunken evening in Reno, he came back to his car and found that someone had left him a tombstone engraved “Chico Pete, d. 1952.” He later gave it to Hopps, who was known as “Chico” to his friends after various wild vacations south of the border. Hopps kept it at Syndell Studio, then returned it to Kienholz, who moved it to his studio in Hope, Idaho, in 1975, where it remained.)

In Las Vegas, he scored a curious job teaching art at the Taffy Hill School of Self-Improvement, which turned out to be a front for an escort service. After a quick departure from that job, he earned money making window displays for liquor stores.

Kienholz did not attend art school, but, in 1947, he put in a couple of semesters at Whitworth College in Spokane, where his fling with a young woman resulted in marriage and a son. They moved to Cheney where Kienholz briefly studied architecture at Washington State College while working nights as an attendant at a mental hospital. “Conditions were bad, like One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest,” he said. One of his wards committed suicide by strangling himself with his sheets. After about a year and a half, he had divorced and gone back to roaming in his 1932 Buick coupe, which with its top removed from the trunk, served as a makeshift pickup. “I had a black Great Dane; I had a Puritas bottle full of goldfish; I had some books. I had a tombstone; I had probably fifty or sixty early constructions—a couple of pair of pants and a Botany 500 raincoat—that was about the range of my worldly possessions,” Kienholz recalled.12

He could not conceive of living in New York. “How can you live in a place where you can’t just walk out the door where you live and take a piss in the backyard?”13 So, in 1952, he drove to Los Angeles to pursue his notion of being an artist. “I had nothing, so in a way I risked nothing, except my time, in the early years. It was a big city—I was away from the small-town look-over-your-shoulder, know-your-business syndrome—and I had nothing to risk, so I could do anything I wanted. And that sense of freedom probably produced some of the early directions that I took on in ignorance, certainly.”14

Shortly after moving to L.A., Kienholz had a life-changing toothache. He was too broke to pay a dentist and complained of his plight to a car dealer in the Valley who said that his brother-in-law, a dentist, was an art collector who might be willing to barter. Kienholz drove out to Van Nuys and met the couple. He leaned all of his enamel-on-wood abstract paintings against the berm of their front lawn. After a while, the couple selected one, and the next day, Kienholz went to the dentist’s office and had his tooth pulled out. “Jesus, I’ve come to heaven,” he recalled. “I mean, you know, to be an artist is really worthwhile because I got rid of that tooth which hurt. I was very very pleased with that. It’s the main reason I stayed in Los Angeles. I figured, ‘Boy, I’ve found the right place.’”15

He put a few of his lumpen abstractions in the window of the vacant store where he lived on Ventura Boulevard in Sherman Oaks. Beat poet and sometime heroin addict Robert Alexander knocked on the door and said he wanted to exhibit the paintings in his nearby Contemporary Bazaar, an arts and crafts boutique where poetry books were sold and readings were held. Alexander also wanted to borrow some abstract paintings by Richards Ruben from the Felix Landau Gallery. Together they drove in Kienholz’s truck through tree-lined Beverly Glen and across the broad boulevard of La Cienega. “I saw this gallery,” Kienholz said, “and everything was white and clean and pretty.” He whistled to himself and thought “that is the way it should be. That’s the kind of a gallery I should have.”16

In 1954, Kienholz rented his first studio on Santa Monica Boulevard between Crescent Heights and Fairfax next to that of Howard “Dutch” Darrin, a car designer who had created one of the first sleek fiberglass sports cars, the Kaiser Darrin. Kienholz didn’t have the ten dollars for rent but noticed the space came with a “pretty good couch.” He borrowed ten dollars to pay the landlord, put the couch in his truck, drove twenty blocks west to La Cienega Boulevard, and sold it to an antiques store for eighty-five dollars. He paid back the ten dollars, paid his landlord seven months’ rent, and had five dollars left. “And five dollars was, like, incredible,” said Kienholz, who budgeted himself to live on $1.09 a day.17

Kienholz hauled his paintings around to a few dealers but encountered only rejection so he turned to the manager of a Laurel Canyon coffee shop frequented by local musicians and artists. Acceptance at last! His show at Von’s Café Galleria was reviewed, sort of, by someone who wrote that his watercolors were “almost as excellent as the wonderful food at this spot.”18

There he met eighteen-year-old Mary Lynch, who had hitchhiked south from the Bay Area with her friend, the aspiring but inexperienced actress Diane Varsi. Soon after their arrival, Varsi landed the lead role of Allison Mackenzie in the 1957 movie Peyton Place, for which she received an Academy Award nomination. Afterward, she dated her costar Russ Tamblyn, a one-time child star who had gravitated to the Beat scene. Meanwhile, Mary married Kienholz in 1956 and worked as a claims processor for Blue Cross while he pursued his art and his ideal of building an art scene. They lived in a falling-down house on Nash Drive in woodsy Laurel Canyon that they bought for $5,000. “I was open,” Mary said. “I came from the Beatnik situation in North Beach so anything new was good.”19

Kienholz took over as impresario of the Café Galleria and arranged shows of Edmund Teske’s photographs and the work of other artists. “Then I decided I’d open my own gallery so I’d have a place to show,” he said.20 He contacted Raymond Rohauer, who had rented the Turnabout Theatre at 716 North La Cienega Boulevard, named for two stages where different puppet shows could be held simultaneously. Kienholz proposed removing one proscenium to make it into a theater for Rohauer to show avant-garde films in exchange for a separate space for his Now Gallery; Kienholz also hung an occasional show in the lobby of the Coronet Theater down the street at 366 North La Cienega Boulevard, where Rohauer also screened foreign and art films such as Kenneth Anger’s Fireworks and Jean Cocteau’s Blood of a Poet, both of which were seized by the police in 1957.

By that time, Kienholz had bought a proper pick-up truck and had the driver’s side door lettered: ED KIENHOLZ: EXPERT. City officials must have believed his self-promotion when they hired him as contractor of the all-city art show held annually at Barnsdall Park with a budget of $12,000. That is where the hustler Kienholz first met the ethereal Hopps, who volunteered his help in the staging so that Now Gallery and Syndell Studio could have booths along with the more established galleries of Landau and Stuart. A few months later, after Rohauer defaulted on his theaters’ rent, Kienholz lost Now. Hopps suggested to Kienholz that they combine their galleries into one.

Midwesterner Streeter Blair painted bucolic scenes in a folksy style and sold antiques from a large building on North La Cienega Boulevard. Kienholz had bought furniture from him and even pitched a few games of horseshoes with the transplanted Kansas farmer. Blair’s wife, Camille, also an artist, offered to rent the back of their building to Kienholz and Hopps. Ferus first opened at 736a North La Cienega Boulevard. “We had a strange gallery and showed strange things, but we paid our rent,” said Kienholz.21

Hopps borrowed $200 and Kienholz started renovating the small gallery with a storage area concealed by a curtain. Hopps selected abstract paintings by a dozen artists from Northern California for the first show, rather pretentiously titled Objects on the New Landscape Demanding of the Eye, and set to run from March 15 to April 11, 1957. Kienholz had gotten his friends together and rented a paint sprayer so they could stay up all night working on the gallery, but Hopps didn’t show up. “I’m absolutely pissed that he doesn’t show,” recalled Kienholz. “Well, it turns out that he was out borrowing a Clyfford Still for the first exhibition. And the truth of it is, it’s not important that the gallery was white, but it is important the Clyfford Still was in the gallery. I had no idea who Clyfford Still was, you know; I didn’t have the knowledge at all.”22

Critic Gerald Nordland called that Still painting a “great ochre masterpiece.” Nordland wrote for Frontier, a magazine published by art collector Gifford Phillips, the nephew of Duncan and Marjorie Phillips, who had established the first modern art museum in America, the Phillips Collection, in Washington, D.C. Nordland continued, “The first exhibition was vigorous and forceful and has set a pace which may well be difficult to maintain.”23