CHAPTER FIVE

Okies: Ed Ruscha, Mason Williams, Joe Goode, and Jerry McMillan

On a sweltering summer day in 1956, Ed Ruscha and his best friend, Mason Williams, waited impatiently to set out for Los Angeles. The two had grown up in the same Oklahoma City neighborhood, had attended the same classes, had double-dated to the high school prom, and had even collaborated on an episodic painted mural about the Oklahoma Land Run. Ruscha looked to be on the cusp of manhood, his face defined by high cheekbones, brown hair, and almond-shaped eyes. Williams, squarely built with dark hair, an upturned nose, and a dimpled chin, retained a boyish appearance. Both were blessed with charming Oklahoma accents, a honeyed meld of southern and western tones. Fittingly, they headed off to college together. Ruscha, nineteen, packed his black 1950 Ford with trunks of clothes, school supplies, and sandwiches made by his mother. The car tended to burn oil so Ruscha had a case on hand and, indeed, the car went through thirteen quarts making the 1,250-mile journey west along Route 66. For them, the fact that they were going to college paled in importance beside the fact that they were getting out of Oklahoma City.

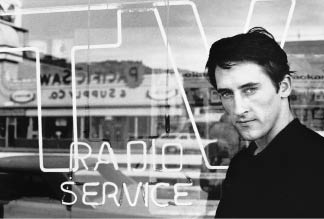

Ed Ruscha

Photograph by Dennis Hopper, © The Dennis Hopper Trust, courtesy of The Dennis Hopper Trust

Edward Joseph Ruscha IV was born in Omaha, Nebraska, in 1937 and was five years old when his parents moved to Oklahoma City. His father was transferred to Oklahoma to work as an auditor for the Hartford Insurance Company, and he remained for the next twenty-five years. A survivor of the Depression, Ruscha’s father had a singular piece of advice for his son: “Always pay cash.”1 He had paid $7,000 cash for their 1920 brick house on Northwest Seventeenth Street in 1942.

Ruscha’s father remained a devout Catholic despite having been excommunicated in 1922 after divorcing his first wife. For many years, Ruscha and his siblings were not told that they had a step-sister, the daughter of that first marriage. “It weighed heavily upon him,” Ruscha recalled. Ruscha’s repentant father attended mass daily, taking his eldest son with him on Sundays, despite the fact that he was prohibited from taking communion or kneeling during the service. Ruscha’s mother, also Catholic, attended church only on occasional Sundays or holidays, and instead of kneeling, she sat with her husband as a show of loyalty. While Ruscha studied catechism, he could not be an altar boy like his neighbor Joe Goode.

While his father traveled for business, Ruscha grew close to his mother, who was gifted with both a sense of humor and of propriety. Her two sons and daughter sent thank-you notes promptly and addressed their elders as “sir” or “ma’am.” A dedicated reader and correspondent, she kept an open dictionary in the dining room and encouraged her children to look up word definitions.

According to Ruscha, his mother’s literary sympathies extended to the creative efforts of Williams, who called her “a godsend.”2 Williams had spent his earliest years in Rule, Texas, where his family had lived a hardscrabble existence in a shotgun house with no indoor plumbing. “We were like a Walker Evans photograph,” he said later.3 Williams’s father, a tile setter, made a better living after bringing the family to Oklahoma City, but young Williams spent most of his free time at Ruscha’s house. “[My mother] hit it off with Mason, who was always spouting poetry and silly stuff,” Ruscha said. “She encouraged him, almost like a second mother. He’d come over and play guitar, folk songs, or country and western.”4

The Ruschas were the last on their street to get a television; such an indulgence was thought to be a bit “show-offy” so the family listened to radio drama, and Ruscha came to value not just the meanings but the sounds of words.

As teenagers, he and Williams discovered a store in town that carried 45 rpm records by rhythm and blues musicians, what Oklahomans called “race music.” Ruscha’s first purchase was the Clovers single “One Mint Julep” with “Lovey Dovey” on the B side. The slow, rocking rhythm and suggestive lyrics promised darkened rooms, close dancing, romance, and mystery. He bought recordings of Stan Kenton, Count Basie, and Billy Eckstine and missed few concerts at the Municipal Auditorium. In 1949, Spike Jones and the City Slickers found Ruscha hanging around the back of the auditorium trying to sneak in. They gave him some money and told him to go buy some eggs. Thrilled by this brush with celebrity, Ruscha did what he was told. When he returned, they invited him backstage where he watched these grown men throw eggs at one another in front of a live audience. The wild array of instruments they played, the jokes, the nutty clothing—Ruscha knew he was witness to denizens of an exotic netherworld. “Music played such an important role in my development as a kid.” he said. “Enough to visualize how big the world was.”5

Ruscha became friends with Jerry McMillan and Joe Goode when all three joined a Classen High School fraternity that held events with a sorority. Dating was fine, but Ruscha was wary of marriage. “In those years people were trying to emulate their parents. Marrying and settling down was an issue to be approached. It all crashed when the book On the Road came out and we started reading beatnik poetry and took an about-face to that old order of thinking.”6

Ruscha, McMillan, and Goode ruled in the art classes, whether drawing still lifes or designing record album covers. Ruscha found a book about Marcel Duchamp in the library, and art and absurdity became entwined in his thinking. He thought about the Dadaists as Goode and McMillan “were cutting up … making these stupid sculptures and lighting them on fire,” Ruscha said. “It all linked with the idea of having madcap fun.”7

By his own account, Ruscha was a mediocre student, receiving Cs in most classes, and occasionally Ds. “I got a B in history class and I was stunned,” he said.8 In art, however, he got all As. “I was aimless. I didn’t know what I wanted to do until the eleventh grade.”9 Just before graduating from high school in 1956, he was awarded first prize in graphic design from the Oklahoma City Chamber of Commerce. At that point, he decided to go to art school.

To avoid being drafted for service in the Korean War, Ruscha joined the navy. After boot camp at the Great Lakes Recruit Training Command near Chicago, he had to commit to two weeks a year on a destroyer, but at least he would be able to attend art school and get out of Oklahoma City. “I knew I couldn’t hack the Bible Belt.… And the East, that was just too old world for me,” he said with a shrug.10

An earlier family vacation to Los Angeles had made a great impact. “The patterns of vegetation, the feeling of acceleration, the corner of Sunset and Vine”—all were potent memories. “Another attraction was the hot rods, the custom cars. I knew I wanted to go to California. That was the only place.”11 Ruscha’s father tried in vain to direct him toward a more dependable profession. “He thought [art] was too ivory tower,” Ruscha said.12 So they compromised: Ruscha would study commercial art in order to pursue a career in advertising.

Ruscha had not contacted any schools before making the trip to Los Angeles. He had heard about Art Center in Pasadena, which had a successful commercial art program. When he went there to apply and found that the classes were full, he heaved a sigh of relief. “They had a dress code!” he said indignantly. “No facial hair. No affectations of Bohemianism, no berets, no sandals, no short pants. You couldn’t be a beatnik.”13 So, Ruscha enrolled at Chouinard Art Institute near Lafayette Park on the eastern end of Wilshire Boulevard where “you didn’t have to have a professional appearance.”14

Nonetheless, Chouinard was a professional commercial art school. Founded by artist Nelbert Murphy Chouinard in 1921 in a modest building on Eighth Street, the school was considered a serious environment for art, even though it was not accredited. “The attitude was that a diploma did not matter. You were judged by the product you came up with,” Ruscha said.15 Walt Disney had asked Chouinard to train artists in the skills required to animate the films he was making. At the time, he could not afford to pay her tuition. She believed in what he was doing and told him to pay her when he was able. Animators were produced, films were made, and Disney later paid her the overdue tuition for every student. (In 1970, Disney facilitated the merger of the school with the L.A. Conservatory of Music to become what is now California Institute of the Arts in the suburb of Valencia.)

Ruscha and Williams rented a room in a nearby boardinghouse on Sunset Place. The August smog was so intense that they went to a drugstore for a salve for their burning eyes. “We’d never experienced air pollution before,” Ruscha recalled.16

Their Chouinard instructors Bengston, Altoon, and Irwin were committed to careers as practicing artists despite the dearth of professional opportunities. Bengston once had his students stretch paper around the classroom and draw and paint on it collectively. At the end of the day, he told them, “Tear it down and throw it away.” Ruscha said, “It was the idea of, ‘Just get in and do the work.’”17

Williams had enrolled at L.A. Community College with the idea of majoring in accounting but spent most of his time in jazz clubs and concerts. Deciding to pursue a career in music, he returned to Oklahoma City and took a crash course in piano with a teacher who told him that he would never become a great musician. With the burden of greatness lifted, Williams decided to have fun. In 1958, he bought his first guitar, an old Stella, for thirteen dollars. He began playing and singing with groups in coffeehouses and clubs and eventually got his songs recorded. He remained in touch with Ruscha from a distance until 1961 when, having joined the naval reserves, he was called to serve on the USS Paul Revere with the U.S. Navy in San Diego. Sailor by day, folksinger by night, he performed at clubs in San Diego with weekend stints at the Troubadour on Santa Monica Boulevard.

After just a few classes, Ruscha abandoned his pursuit of commercial art, drawn by what he called the “bohemian” fine-arts department. Like his teachers, Ruscha was painting in a gestural abstract style until he saw the cover of a 1958 ARTNews featuring Jasper Johns’s Target with Four Faces. He also saw a photograph of Robert Rauschenberg’s 1955 combine Odalisk.

“That just sent me,” Ruscha said. “I knew from then on that I was going to be a fine artist. It was a voice from nowhere; it was the voice I needed I guess; I needed to hear this and see this work. And it came to me, oddly enough, through the medium of reproduction, and so it was a printed page I was responding to, and not the work itself. But the kind of odd vocabulary they used inspired me—it was like music that you’ve never heard before, so mysterious and sweet, and I just dreamed about it at night.… These new voices I was hearing transplanted the temporary excitement I had from Abstract Expressionism, which was the only thing at the time.… The work of Johns and Rauschenberg marked a departure in the sense that their work was premeditated, and Abstract Expressionism was not. So I began to move toward things that had more of a premeditation … having a notion of the end and not the means to the end.… It’s the end product that I’m after.”18

Ruscha started incorporating words into his paintings, an effect not appreciated by the Chouinard professors. One teacher was notorious for expressing his disapproval by taking out a cigarette lighter and setting fire to students’ work. Ruscha was out of town when this happened to his collage so his indignant friends stormed the dean’s office to protest the vandalism. When Ruscha heard about it, he thought he must be onto something if it so upset the faculty.

During the summer recess, Ruscha returned reluctantly to Oklahoma City. The trip home reinforced his decision to leave. “[I was] so glad that I had gotten away from the Bible Belt and all those people. Because there was just no room for poetry.… An artist would starve to death there.”19 His ceaseless praise of L.A. weather, women, and cars—not to mention art school—convinced Jerry McMillan to follow him west. The following year, they convinced Joe Goode.

Goode described his father as a “wannabe artist” who worked as a display manager at a department store.20 He taught Goode to draw by walking with him into the woods one day and spending an entire afternoon making a precise rendering of a fallen log. After his parents divorced, Goode and his father sat in front of the television together doing line drawings of Jack Benny. Goode thought his father was trapped by family ties and vowed to avoid such responsibilities. As a teenager, Goode lived with his mother, who had remarried, but he did not get along with his stepfather. He dropped out of high school and earned pocket money by playing cards and shuffleboard in bars. His gloomy future was changed by the return of his two friends from Los Angeles. “By then, I knew I wanted to study art and I thought, ‘If I leave here, no matter where I go, at least I won’t embarrass my mother by what I am doing, if I want to gamble or whatever.’ As … it started snowing, I thought, ‘I’m going to California.’”21

Goode had never flown before. As his Los Angeles–bound plane banked over the ocean before landing at LAX, he looked down at the vast grid of lights and thought, “Jesus, how am I ever going to find anybody?”22

McMillan and Ruscha were taking classes at Chouinard, but Goode had come to the big city with only sixty-five dollars. Slightly built, with blue eyes and a quick wit, Goode was hired to run a printing machine at a shop on Beverly Boulevard. “Two weeks go by and I’m due to get a check,” Goode recalled. “This guy said, ‘All right, just have a seat there.’ He brings a check and sits next to me and puts his hand on my leg and starts rubbing. Oh man, I freaked. I never knew anyone who was gay.… I was twenty-one but mentally much younger.”23

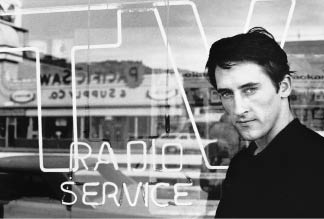

Joe Goode, Jerry McMillan, Ed Ruscha, and Patrick Blackwell in their shared studio, 1959

Photograph by Joe Goode, courtesy of Joe Goode

It was a startling introduction to the city. Goode enrolled at Chouinard in January 1960 and settled in with Ruscha, McMillan, Patrick Blackwell, and Don Moore (also from Oklahoma City), in a rented house at 1818 North New Hampshire Avenue in Hollywood. (Wally Batterton, another student, had moved out.) They took their meals at Norm’s restaurant (later the subject of Ruscha paintings) and had one extra room that they shared as a studio. Goode said, “Jerry had a wall, I had a wall, Ed had a wall, and Pat Blackwell had a wall. We could be in there at the same time.”24

Goode had his first revelation about art in Robert Irwin’s class that fall. “He’s a very engaging talker. So when you are subjected to him as an authority figure and he is telling you in a million different ways you can do anything you want, that was the biggest influence,” Goode said.25

Despite his determination to avoid responsibilities, just one year into his studies, Goode married ceramics student Judy Winans. A few months later, they had a baby daughter. To support his family, Goode worked three part-time jobs while taking classes. Exhausted from the effort of going to school and supporting his family, Goode had to drop out six months later. He threw himself into making art for himself. “When I came home from work, these milk bottles would be sitting out on the steps. That is how I got the idea of the milk bottles with a plane in front of them and a plane in back of them. A way of seeing through something.”26 This homey inspiration led him to create large monochrome canvases each with the outline of a single milk bottle at the base. Instead of hanging them, Goode leaned them against a wall with actual glass milk bottles, also painted, on the floor in front of them. Within a year, this work propelled Goode into the surging realm of Pop art at a time when no one really knew what it meant to be Pop.

* * *

Ruscha completed his studies at Chouinard in 1960. Despite his dedication to his own art, he supported himself doing layout and graphics for an advertising agency, Carson-Roberts, housed in a glass and steel modern structure in West Hollywood. He designed the original Baskin-Robbins illustration of the single scoop, double scoop, and triple scoop.

In 1961, he left to join his mother, Dorothy, and brother, Paul, on a spring tour of Europe. His father had died of a stroke, and his enterprising mother bought a Citroen in Paris. The three of them drove through Spain, Italy, Greece, Yugoslavia, Austria, Germany, England, Scotland, Ireland, and France. After his family returned to Oklahoma, Ruscha stayed in Paris for two months. Visiting museums, he came to the same conclusion held by many of his Los Angeles peers. “I found that I had no scholarly interest in art whatsoever.” he said.27 Not the art produced before the twentieth century, at any rate. He was bowled over by his actual encounter with Rauschenberg’s “combines,” however—radical combinations of found objects, images, and painting, on display at the Iris Clert Gallery. And, not surprisingly, he loved the Parisian lifestyle. While there, he transformed foreign words into small oil paintings and took photographs of street signs, harbingers of the art that he would pursue.

On his return, Ruscha stopped in New York City and went to the Leo Castelli Gallery. Ivan Karp, then working for Castelli, took Ruscha into the back room to show him a painting of a tennis shoe by Roy Lichtenstein. “It was completely aggravating and inspirational,” Ruscha recalled, realizing that someone else saw popular culture as a valid antidote to Abstract Expressionism.28 He did not want to stay in New York, however. “I was overwhelmed by the number of people in New York and the impersonality of the place,” he recalled. “I feared being chewed up by the whole machine.”29

Back in Los Angeles, Ruscha made a radical leap by applying his graphic arts skills to a series of large paintings with product names such as “Fisk” in white letters with a white tire on a turquoise ground. Another large canvas has the word “Spam” occupying the top while a rendering of the tinned meat in its actual size—Actual Size is the title of the painting—hurtles across the canvas like a rocket with yellow flames trailing behind it. Ruscha said, “The word ‘Spam’ is similar to the sound of a bomb. So you have this noisy thing at the top and then this projectile flying after the noise, arcing across the sky like a shooting star.”30

Ruscha’s paintings were included in the first Pop art exhibition held in the United States: The New Painting of Common Objects at the Pasadena Art Museum from September 25 to October 19, 1962, just two months after the Ferus show of Warhol’s soup-can paintings. Organized by Hopps who, with Blum, had visited the studios of the Pop artists in New York, it included three works each by eight artists: Warhol, Lichtenstein, and Jim Dine from New York, and Ruscha, Goode, Phillip Hefferton, Robert Dowd, and Wayne Thiebaud, all from Northern or Southern California. Hopps considered this group to be “post-Rauschenberg, post-Johns” in their use of everyday objects and, like many others, he was trying to comprehend the significance of this increasingly widespread development. Instead of a catalog, he asked the artists to contribute line drawings that were mimeographed and put in an envelope as a portfolio.31

Hopps asked Ruscha to create the exhibition poster. Thinking it should have the same Pop appearance as the art, Ruscha telephoned a commercial printer who usually ran off announcements for boxing matches. He dictated his copy with only one directive: “Make it loud!” The black and red type on a bright yellow background was the ideal off-the-shelf look. John Coplans was visiting from San Francisco and Hopps said, “Come on, help me hang it—we have no staff.” Coplans recalled, “There we were, the director and the critic, hanging the show I was writing about days later.”32

On the West Coast, at least, the show was a sensation. Ruscha’s painting of a smashed box of Sun-Maid raisins rendered in the top half of a canvas with the word “Vicksburg,” site of a Civil War battle, covered in a yellow wash of paint on the bottom, sold for fifty dollars to C. Bagley and Virginia Wright, art collectors from Seattle, where Wright had just funded the building of Space Needle for the 1962 World’s Fair. Amazed by this early endorsement of his talent, Ruscha said, “I just couldn’t believe that I actually got money through this thing.”33

The show was featured in Artforum, a magazine conceived that year in San Francisco with a focus on West Coast art. Goode’s painting Happy Birthday, a purple monochrome canvas poised behind a glass milk bottle covered in orange paint, was on the cover of the distinctive ten-and-one-half-inch square magazine, a format conceived by a graphic design student in San Francisco.

Coplans, an English painter of geometric abstractions who was then teaching at the San Francisco Art Institute, had started contributing reviews to various magazines. He was instrumental in founding Artforum with Oakland printer John Irwin. Reviewing the show, he complimented Goode on making “two of the loneliest paintings imaginable … powerful, deeply moving and mysterious paintings,” and declared that Ruscha had done no less than create a “totally new visual landscape.”34 He concluded his review with a chronology of influences that included Duchamp, Man Ray, Schwitters, Eduardo Paolozzi, and Richard Hamilton, adding that his colleague, English critic Lawrence Alloway, had coined the term “Pop art” in 1954. Like Hopps, Coplans saw the movement of Pop art as evolving out of interest in the printed word and everyday objects as seen in assemblage and Beat poetry. Influenced by the multitalented Los Angeles designer Alvin Lustig, who created graphic book jackets for New Directions, Knopf, and other publishers, Ruscha confidently pursued the appearance as well as the meaning and sound of words without images. His next sale was a large painting of one word from the title of a popular comic strip in curvaceous red letters on yellow above a panel of blue: Annie.

Ruscha traded Annie to Goode in exchange for one of his milk-bottle pictures. Shortly after, Blum asked Ruscha to join Ferus with the enticement that his client Betty Asher would buy Annie. Ruscha called Goode and pleaded, “Can I trade it back from you?”

“Sure,” said Goode, adding later, “That is the way we worked. We didn’t have any money so that always came first.”35 The following year, Asher rewarded him by buying a milk-bottle painting for $300 and persuading red-haired comic actor Sterling Holloway to buy one as well. Holloway became another important collector.

Ruscha made a small version of Annie for his intimate friend Ann Marshall, daughter of actor Herbert Marshall and best friend of Michelle Phillips, the gorgeous nymphet singer of the Mamas and the Papas. Along with Toni Basil, the dancer and choreographer who was dating Dean Stockwell, and Teri Garr, the dancer and actress who was dating Bengston, these adventurous and beautiful young women embodied the essence of California girls. They became regulars at Ferus and Barney’s and feckless feminine models for photographs by Dennis Hopper.

Ruscha was stunned to be invited to join the elite Ferus artists who were, to him, “like a collection of altar boys with black eyes,” he said. “There were other progressive galleries operating then, but Ferus was the most progressive, and they had a much sparer approach to showing art. If you wanted to put one tiny painting on a big wall you’re welcome to it. The artist is the boss.”36

Rolf and Doreen Nelson’s wedding party at his gallery, 1966

Courtesy of Doreen Nelson

Goode, on the other hand, was not asked to join Ferus, despite the critical acclaim for his work. “The great thing about Ed [Ruscha] is that Ed has no enemies,” Goode said. “Everybody could learn a great deal from Ed.”37 Goode held no resentment toward his friend but was bitter toward Blum, despite being invited to join a promising new gallery: Rolf Nelson.

Nelson, who had worked for Martha Jackson in New York, came west to run the short-lived Los Angeles branch of James Newman’s Dilexi Gallery. A Parsons-trained artist turned dealer, Nelson opened his own gallery on 530 North La Cienega Boulevard a year later. As Blum cast off artists, Nelson welcomed them, including Llyn Foulkes, who performed music on a one-man band of his own invention and painted landscapes based on postcards of his Eagle Rock neighborhood, and George Herms, the assemblagist and filmmaker who had adopted Berman’s mantra “Art is Love is God.”38

The Common Objects show turned out to be a big break for the youngest artists, Ruscha, twenty-four, and Goode, twenty-five, who had been introduced to Hopps by Henry Hopkins. Hopkins had defected from a family of Idaho agronomists to study art at the Art Institute of Chicago. He was drafted to serve in the Korean War in 1952. Mustered into the photography department and posted to Europe, he visited museums and became interested in art history. On the G.I. Bill, he enrolled at UCLA to get a master’s degree in art history under the revered art historian and artist Frederick S. Wight.

As director of the university art gallery from 1953 to 1972, Wight had shown a number of modern artists, including Arthur Dove, Charles Sheeler, John Marin, Modigliani, Picasso, Matisse, Arp, and even Claes Oldenburg, bold choices in the conservative city. He also showed his own landscape paintings at the Esther Robles Gallery.

It was at UCLA that Hopkins had befriended fellow student Shirley Hopps and her husband Walter. James Demetrion, who became a curator at the Pasadena Art Museum, was a graduate student at that time. Together, they decided it was important to locate the next group of young artists to supplement the core group at Ferus.

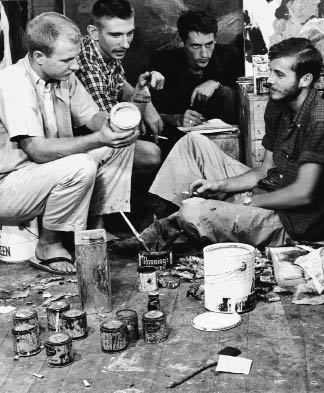

Backed by a group of three young lawyers who wanted to start a gallery, in 1961 Hopkins opened Huysman, named after the Symbolist French novelist, at 740 North La Cienega Boulevard with a small group show called War Babies. The show and gallery gained instant notoriety for its controversial poster, a photograph staged and shot by Jerry McMillan, of four artists eating the food of their ethnic stereotype: Jewish Larry Bell with a bagel, Japanese American Ron Miyashiro with chopsticks, African American Ed Bereal with a slice of watermelon, and the Irish American Catholic Joe Goode with a mackerel. An American flag was draped over the table where they sat, and that detail alone caused such an uproar that it contributed to the demise of the gallery. “We were attacked from the left for using clichés. We were attacked from the right, including the John Birch Society, for desecrating the American flag,” Hopkins said. “It was one of the first racially integrated exhibitions in Los Angeles, which we weren’t thinking that much about, but it caused a wonderful furor.”39

It also launched McMillan’s career as a photographer who documented the L.A. art scene and took some of the most intimate portraits of Ruscha. In his own work, he was an innovator, playing with the boundary between a two-dimensional image and a three-dimensional object using photography processes.

Ed Bereal, Larry Bell, Joe Goode, and Ron Miyashiro at Huysman Gallery, Los Angeles, 1961

Photograph by Jerry McMillan, © Jerry McMillan, courtesy of Craig Krull Gallery, Santa Monica

Hopkins, still a student, thumbed his nose at the conservative political and social forces still in power in Los Angeles. In Artforum, he wrote a cogent rebuttal to a 1962 article, “Conformity in the Arts,” written by Lester D. Longman, the art department chair at UCLA, which decried the work of Rauschenberg, Yves Klein, Jean Tinguely, and others as evidence of an age of “anxiety and despair, of existential nausea and self pity.”40

Hopkins wrote his dissertation on the modern art of Los Angeles, a topic that did not exist according to his UCLA advisers, though Wight granted permission. Such ambition caught the attention of curator James Elliot at the L.A. County Museum of History, Science, and Art in Exposition Park. With Elliot, Hopkins worked on the exhibition Fifty California Artists, which included Irwin and Kienholz, along with more established artists. The show traveled from UCLA’s gallery to the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York and other museums around the country. The L.A. County Museum hired Hopkins as assistant curator, but his salary for the first year had to be paid by collector Marcia Weisman because the museum had not allocated funds for modern art.

Hopkins wrote the first published (and positive) review of Warhol’s soup-can exhibition for Artforum. He was also the first to purchase a word painting by Ruscha: Sweetwater. It came to a tragic end when a student took it from Hopkins’s office and painted over it. (Hopkins frequently told this story to the amusement of many but without much real forgiveness.)

Soaring from the attention that came with Common Objects, the following year Ruscha and Goode decided to hitchhike to New York. They rode with amphetamine-fueled truckers and, when no cars offered rides, they took a bus that was so crowded that Goode slept on the floor. Then they had an experience that could have been lifted from a cheesy porn film. A young woman stopped and, after a brief chat, asked if she should get her friend and show them the sights in the nearby small town. That sounded like a great idea. At her suggestion, they took off their clothes to go swimming in a pond while waiting for her return, which, rather predictably, she never did.

When they finally reached New York, Goode agreed with Ruscha that it would be impossible to make art there. “One of the great things about working [in Los Angeles] was that most artists didn’t care about what was happening in New York,” Goode said. “What Irwin stressed is what everybody out here believed. You can do what you want and this idea of having a theory tied around your work, you don’t have to do that. That is what I really liked. It always looked stifled to me, New York art, because of the heavy reliance on European art.”41

In New York, Larry Rivers took them to the Five Spot to hear Thelonious Monk. Warhol invited them to lunch, and Ruscha showed him his first book of black-and-white photographs, Twentysix Gasoline Stations: Standard stations, Texacos, and so forth, with no essay, in a five-by-seven-inch paperback. Warhol looked through the book with his deadpan serious expression. “Ooh, I love that there are no people in them.”42

Not long after, Ruscha painted Standard Station, Amarillo, Texas, a long horizontal canvas roughly five feet tall and ten feet long in flatly commercial shades of red, black, and white. “I think they become more powerful without extraneous elements like people, cars, or anything beyond the story.… I wanted something that had some industrial strength to it.”43 Dennis and Brooke Hopper bought that painting, which made sense in that Hopper had taken an iconic photograph of two Standard signs at a gas station on the corner of Santa Monica Boulevard and Melrose Avenue as seen through the windshield of his car: Double Standard. In the 1960s, gas stations could be slightly exotic. Tom Wolfe described the Union 76 in Beverly Hills as a “Futurama Pagoda” designed by Jim Wong of Pereira and Associates: “What Wong has done here with electric light sculpture—as an artist—goes so far beyond what serious light sculptors like Billy Apple and Dan Flavin (and serious architects, for that matter) have yet attempted; it poses a serious question for art historians.”44

Ruscha knew intuitively that there was something unsettlingly special about his small book of gas station photographs even if Philip Leider, the editor of Artforum, wrote that he found himself “irritated and annoyed” by it. Ruscha showed it to his sometime girlfriend Eve Babitz, who went on to write a series of scandalously funny memoirs beginning with Eve’s Hollywood.

“We were driving down to have dinner at La Esperanza in the Plaza,” she recalled. “We used to get enchiladas rancheras with sour cream, melted cheese, avocado.… So I look at this book and said, ‘Why did you make this book?’ He said, ‘Somebody had to do it.’”45

Ruscha became a regular at the unruly but warm Babitz household in Hollywood, where her violinist and musicologist father, Saul Babitz, and artist mother entertained the Igor Stravinskys and other Europeans visiting or relocating to the city. Ruscha became friends with the entire family. “He would come over to our house all the time. And for Thanksgiving. My mother would make these huge meals. Ed’s thing was ‘May Babitz sure is good to her boys.’ He was my boyfriend for a long time.”46

Babitz’s portrait was included in a Ruscha project for the 1970 Design Quarterly called Five 1965 Girlfriends. Another girlfriend was the slim and stylish Danna Knego. Ruscha had met her at Hanna-Barbera studio, where she worked as an artist inking the line drawings of animators.

Meanwhile, Goode’s marriage had crumbled under the strain of poverty and creative ambition. After divorcing his wife Judy in 1964, Goode dated Eve’s sister, Mirandi, who introduced him to the music of the Beatles. Both daughters were regulars at the clubs proliferating on the Sunset Strip. Goode remembered going with Mirandi to hear Donovan perform and seeing John Lennon hop on the stage for an impromptu jam.

Knego, a slender twenty-one-year-old with high cheek bones and clearly set brown eyes, was living at home with her mother. Her father, who had left the family when she was eight, had been an actor, and a close friend of Robert Mitchum. Knego and Ruscha shared a passion for the stories and remnants of old Hollywood and the historic city. “We’d drive around L.A and look at different things and feel the nostalgia even then for the old buildings,” she said.47

Many such buildings could be found in Echo Park on the east side of the city where stucco bungalows nestled on the hills that rose around a large pond with blooming lotus plants. In 1964, Ruscha had moved to a small house on Vestel Avenue. He preferred to live near his circle of Oklahoma friends on the east side of town rather than follow the rest of the Ferus artists as they moved to Venice Beach.