CHAPTER SIX

Bell, Box, and Venice

Irving Blum honed his relationship with Leo Castelli in order to exhibit New York–based artists Frank Stella, Ellsworth Kelly, and others who were celebrated for their clean geometric abstractions. In many ways, the work was not unlike that being done by Karl Benjamin, Lorser Feitelson, John McLaughlin, Frederick Hammersley, Helen Lundeberg, and June Harwood, an older and more established group of Los Angeles artists supported critically by Harwood’s husband Jules Langsner. But Blum wanted to expand his New York network, and he added no more Los Angeles artists to the gallery apart from Larry Bell.

Bell was born in Chicago in 1939 but raised after 1945 in the sprawling L.A. suburb of the San Fernando Valley. His father sold insurance. His mother helped but was creative and eventually went back to school to study art. Bell was an attractive, wisecracking kid and a mediocre student at Birmingham High School in Van Nuys. “I was a flake of a student,” he said.1 Yet, his ability to draw cartoons got him a PTA scholarship to attend Chouinard during summer school. He enrolled full-time in 1958 with the vague notion of becoming an animator. He rented a room four blocks away from the school in a bright pink boardinghouse, the Shalimar, which once belonged to Charlie Chaplin.

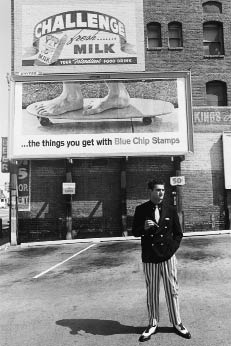

Larry Bell

Photograph by Dennis Hopper, © The Dennis Hopper Trust, courtesy of The Dennis Hopper Trust

Bell was partially deaf, though the condition was not diagnosed correctly until he was forty-six. He felt overwhelmed by the pressure at Chouinard and dropped all of his classes, apart from a watercolor course at night with Robert Irwin, who encouraged his splashy efforts. “He was the first person to take a real interest in what I was doing,” Bell recalled later.2

Irwin was renowned for his Socratic method. “My ideal of teaching has been to argue with people on behalf of the idea they are responsible for their own activities,” Irwin asserted. “Because once you learn how to make your own assignments instead of relying on someone else, then you have learned the only thing you really need to get out of school, that is, you’ve learned how to learn. You’ve become your own teacher.”3

Inspired by Irwin, Bell returned to Chouinard in 1959 and began making odd geometric paintings with two opposing corners removed from a square or rectangle. Herb Jepson, who had joined the Chouinard faculty, taught drawing. In the class, Bell did not draw the figure as assigned but repeatedly drew squares and rectangles. When asked about this, Bell innocently explained that he was transcribing the metaphysical aspect of the assignment. Jepson suggested Bell visit the school’s “aesthetic advisor.”

Bell dutifully showed up for several sessions with this advisor to explain his art, which had grown more abstract and sophisticated. Bell was perfectly pleased with this arrangement until his roommate let on that the advisor was a psychologist employed by Walt Disney, adding, “the school hired him to weed out the weirdos.” Bell said, “I had thought that for once I was making decisions about my work and where I was going and this guy had just set me up because he thought I was some kind of nut. I went back to the school, took out all my stuff, and I never went back.”4

Bell used his tuition money to rent a studio and got a job at a framing shop in the Valley. He attached leftover pieces of mirror to his paintings of geometric shapes to add the element of reflection to the illusion of dimension. Over the next two years, he transformed those geometric paintings into “constructions,” boxes made of mirror or glass that dovetailed perfectly with the glossy work being made by Kauffman and Bengston. “I realized I’d been making illustrations of volumes when what I really wanted to do was make the volumes themselves,” he said later. “At that point, I became a sculptor.”5

In 1962 he discovered a small manufacturer who had the equipment to coat a clear glass surface with a prismatic mist that lent his boxes a transcendent glow. Bell recalled, “I found this guy who did this vacuum coating process. I remember when I looked at the piece I just couldn’t believe it. It was the most fantastic thing I’d ever seen in my life. Bengston was a little bit jealous.”6

Irwin introduced him to Hopps and Blum. Bell so wanted to be part of the Ferus scene that he decided to play upon their sympathies to get his first show: “I actually thought I was going to get drafted into Vietnam in 1961. I went to see Walter Hopps and said ‘Walter, I think I’m going to have to go into the army. I’d like to have a show.’ He and Irving came down and looked at my stuff and said OK. I did a show the following year. As it turned out, I did get drafted, but I was rejected. When I came back from the induction place down on Olive and Olympic, I went banging on Bengston’s door. He opened the door and starting laughing. ‘Man, I knew they weren’t going to take you!’”7

After Bell’s grand opening at Ferus on March 27, 1962, the gang adjourned to Barney’s. “I was twenty-two. I walked in and Barney said ‘Congratulations, I’m buying you a drink. What do you want?’”8 Bell was stunned by the gesture. “That guy was so tight his asshole squeaked when he walked.”9 They closed down the bar that night at two in the morning as Barney called out, “‘Last call, last call for al–ca–hol.’”10

* * *

Later that year, just before Christmas, Bell received an unexpected check for $2,000 from the Copley Foundation that not only provided validation but also enabled Bell to produce larger boxes of coated glass.

Copley also brought Marcel Duchamp to visit Price, Irwin, and Bell. No one bothered to tell Bell, so when he heard the knock at the front door, he assumed it was a building inspector. (It was illegal to live in working studio spaces in those days.) After the persistent pounding continued, he peered through the window and saw three men in suits. He recognized Copley, who introduced Duchamp and Richard Hamilton. Bell often did not hear parts of conversations, and on that occasion he did not realize that his visitor was the great Duchamp. He chatted away in a relaxed and irreverent manner until he overheard Copley say something to “Marcel.” From that moment on, Bell was intimidated; he could barely utter a word. The trio left, but not before Duchamp, who once said, “I don’t believe in art, I believe in artists,” invited him to visit when in New York.11 A year later, in 1964, Bell accepted the offer.

“Teeny took me into the parlor and brought in a tray with tea and cookies. She closed the door and there I was with the great man all by myself. There were Picabias, Magrittes, and a Brancusi wooden blonde Negress up on the armoire. It was a heavy moment. When I asked what he was doing, he said, ‘I’m working on a show of early work.’ I said, ‘Really, how early?’ He said, ‘Oh, I was four or six.’”12

It was at the Duchamp opening at the Pasadena Art Museum that Bell met his future wife, Gloria Neilsen, who was twelve years younger than her sister Shirley Hopps and just as pretty. The two blondes went to Western Costume in Hollywood and rented laced bodices and short skirts in red, white, and blue to attend the black-tie event. “They both looked so cute, and Gloria in particular just knocked me out,” Bell recalled.13 Bell and Neilsen were married three years later in a Las Vegas drive-through chapel.

Unlike Ruscha, who did not integrate his social life with that of the older Ferus artists, Bell made a point of ingratiating himself with Bengston, Kauffman, and Altoon. He said, “I come from a lower-middle-class family in the San Fernando Valley. I didn’t know shit about anything. I lived vicariously off these sophisticated young men.”14

Bell followed the migration of Bengston, Price, Altoon, and Irwin to the beach. Initially, some lived in Ocean Park but most moved to the less expensive environs of Venice. Bell rented three thousand square feet of studio space for seventy-five dollars a month on Marine Street, two blocks from the ocean, in what had once been, in the early decades of the twentieth century, a resort with colonnades and canals built in simulation of Venice, Italy. By the 1960s, the beach was lined with oil derricks and the neighborhood had grown dangerous and dirty, “where the debris meets the sea.” Yet it was a magnet for struggling artists and poets. The Beats had taken over the Venice West coffee house for marijuana-stoked poetry readings. The Ferus crew continued to drive into town to drink at Barney’s, but they had breakfast together at a café on Pacific and Windward. Asked what profound topics of discussion might have engaged them, Bell replied with practiced nonchalance: “Pussy.”15

Altoon lived next door to Bell, and Irwin was one block to the south, not far from Bengston and Price. New York transplant John Chamberlain shared a nearby space with Neil Williams. Other younger artists experimenting with the properties of pure light, Doug Wheeler, James Turrell, and DeWain Valentine, soon moved into the same neighborhood. “The reason was it was cheap,” Bell recalled.16 (In 1966, Bell bought a nearby building at 74 Market Street for $6,000 and the bank balked at giving him a loan, protesting that it wasn’t worth $6,000.) “Every commercial storefront was empty and had been for a couple of years.”17

The artists’ proximity to one another accelerated their growing interest in the properties of light, the nature of perception, and how those factors might be utilized in their art. It was easy to overlook their run-down environs when the sky shifted daily from the soft, gray dawn to a perfect clear blue to a vibrant tangerine and pink sunset. The magical light flooded into their studios, accompanied them on their strolls along the beach, and led them to reflect upon the best ways to capture the experience.

This obsession with light was a historic preoccupation in Los Angeles and the principal reason that the movie studios had moved there from the gloomy East Coast. Directors valued the smooth, golden quality of early morning light as the most flattering for their leading ladies. As it had for the Impressionists in the south of France, sunlight inspired a new crop of plein air painters in the 1920s known as the Eucalyptus School, who captured the whitecaps on the Pacific Ocean and fields of poppies near the Pasadena arroyo. Later, Modernist architects such as the Viennese Richard Neutra devised houses with entire walls of glass to take advantage of the light and the steady climate.

These artists were not stuck in the European past; they sought out new materials that would best serve contemporary explorations. Glass, plastic, and acrylic replaced canvas and paint. Precious little time was spent discussing their art, though they took note of one another’s discoveries. Irwin, Kauffman, Bell, and Bengston especially were light-years and a continent away from their chatty predecessors at the Cedar Tavern in New York.

Bell grew closest to the caustic Bengston. “You could hang with this group if you were serious about what you did. You had to take a lot of shit and be ready to dish it right back. But it was all based on a profound love and sense of humor. Nobody thought there was any money in doing this stuff.”18

Bell was rarely seen without an outlandish hat, tie, or shoes. Walter Hopps used to call Bell “luxury” because Bell and Bengston would haunt cheap thrift stores and buy a whole suit for a dollar. Often the “luxe” clothes were handmade, such as silk ties from Sulka with seven folds. Bengston made belts with stitched-in nicknames for each of the Ferus artists. Bell was “Luxe” while newcomer Ruscha got the insulting name of “Waterboy.” Later, when Ruscha was showing throughout Europe and New York, Ed Moses teased Bengston: “Who is the waterboy, now?”19

Bell’s work sold but, like the other artists, he did not make much money at first. According to Blum, “The gallery was very much like a club. We shared whatever money we had.… I mean me and the artists … would see each other several times a week and share meals and scratch to get by.”20 The gallery was consistently helped along by Shirley Hopps’s paycheck from the University of California–Riverside, where she was assistant professor of art history. Walter’s salary as director of the Pasadena Art Museum was modest.

Collector Betty Asher and her physician husband Leonard helped to support the gallery and were the first to buy one of Bell’s mirrored boxes. They lived in a Spanish-style house in Brentwood, where they often had Blum and the artists for dinner and held charity poker games, letting the poorest artist win. Their son, Michael Asher, became an artist whose Minimalist work was in the spirit of Kauffman and Irwin. Today he is better known as a Conceptual artist and is an influential teacher at the California Institute of the Arts.

For Bell, perception held sway over conception. His glass boxes were originally decorated with spray-painted patterns. Then, as he gained confidence, he simplified his creations. “I finally realized that it was the sensuality of the surface quality which was what I was working with, and what I was able to do with the coating process was to keep the same surface quality but enhance the way light was either reflected or transmitted.”21 As Bell’s breakthrough came at a time when Donald Judd was producing his early boxes of metal and wood, it appeared to critics that a uniquely Southern California Minimalism was being also born.

Bell quickly became the gallery’s rising star. Blum explained, “Arnold Glimcher came and said, ‘This guy’s a genius.’ Because he was the youngest, it didn’t sit well with the others.”22 Glimcher needed ten boxes for a 1964 show at Pace, his New York gallery. Blum asked Bell how long it would take him to make twenty of the boxes—ten for Glimcher and ten for himself—and what it would cost. Bell reported that it would take six months and cost $20,000. Glimcher sent a $10,000 check to Blum, who in turn secured a $10,000 loan from his backer Sayde Moss. With $20,000 in hand, an excited Bell went to work.

Bell confided news of this astonishing windfall to Bengston, who immediately stormed into Ferus. “Irving,” he said, “I want $20,000.”23 Blum explained that it was not possible. There was no waiting list for Bengston’s paintings, no impending show in New York. An indignant Bengston threatened to quit the gallery and, in a fury, attempted to convince others to leave as well, but his friends were unmoved. After that, Bengston left Ferus and was no longer the ringleader.

Bell was confused and troubled by his friend’s reaction. He was even more upset by the fact that Bengston had confronted Robert Irwin and the two had wound up in a brawl that concluded their testy friendship. “You either had to play the game Billy’s way or not play,” Irwin said. “At one point I grabbed him and threw him up against a wall and told him to get the fuck out of my life.”24 When Bell tried to patch things up, Irwin told him not to bother. The artists, who once had had lighthearted fun at Barney’s together, were each now on a more urgent course.

Bell made friends with Donald Judd and other rising artists in New York. In 1965 his reflective glass boxes sold briskly at Pace. “I made more money when I was twenty-five than my dad made in his whole life. I was totally unprepared,” Bell would later say. Success came at a cost. “It gave me a nervous breakdown by the time I was thirty and turned me into an alcoholic.”25 He grew rich while his Los Angeles friends remained broke. “I felt really guilty about it. A lot of the money I made I just pissed away, just because I didn’t feel that I should have it.”26

Meanwhile, Glimcher took on Irwin and Kauffman. “They were giving us money and my first show back there, gee whiz, they paid for a first-class airline ticket,” Kauffman said. “I didn’t know how to deal with all that.”27 Glimcher rented a loft for Bell to pursue his glass sculpture in New York. Kauffman rented one on Seventeenth Street in Manhattan that he shared with John McCracken, who also showed with Pace. McCracken, Kauffman, and Ruscha were selected for the Cinquième Biennale de Paris at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris in 1967. The same year, Kauffman, McCracken, Bell, and Ron Davis were shown with Judd and Flavin in A New Aesthetic at the Washington Gallery of Modern Art. In her catalog essay, critic Barbara Rose claimed their work “portends a brilliant world of color, light, and direct experience.”28

After Bengston’s diva departure from Ferus, he broke his back in a motorcycle accident, which left him paralyzed for four days. He had remained friends with the soft-hearted Bell and, unable to live on his own, slept on Bell’s couch for four months, utterly alienating Bell’s new wife. “He was awful, cranky,” Bell recalled. “His mother knitted me a beautiful afghan, which I still have, for taking care of him.”29

Disciplined in his physical habits, Bengston rehabilitated himself by putting on his motorcycle leathers and boots and running up and down the stairs to his studio thirty times a day. He’d then ride his bike for four hours. A few months later, he began an even less conventional form of physical therapy by going out dancing at the different clubs on the Strip. “I was sort of a dance hall slut at the time. I’d work out in the day and go dancing at night. At that time, the Whisky, Gazzaris, Ciro’s were dance clubs. Primarily rock ’n’ roll, Ike and Tina Turner, the Temptations, stuff you could really wing with,” he later said.30

Bengston was on hand for one of the legendary performances of Otis Redding, who stomped the stage so hard that the whole club filled with dust rising from the floor. In 1966, Whisky a Go Go owner Elmer Valentine had Redding and his ten-piece Memphis band for four nights of performances that were remembered as legendary after the twenty-six-year-old Redding died the following year in a plane crash. Ry Cooder played in the opening act, Rising Suns, and recalled that it was a “super hot show, nothing like anyone had seen in Los Angeles.”31

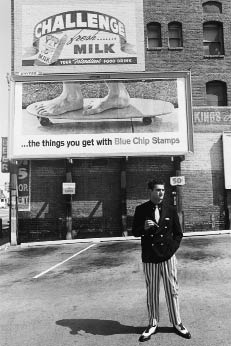

Ann Marshall in front of Billy Al Bengston painting at actor Sterling Holloway’s house in 1965

Photograph courtesy of Billy Al Bengston

One night, Bengston went to Ciro’s to hear the Byrds, who were friends with Mary Lynch Kienholz and involved with the Ferus scene. Bengston hung out with Teri Garr, Ann Marshall, and Toni Basil. Though romantically involved with Garr, he was such close friends with all of them that he eventually combined their initials to name his daughter: Blue Tica—standing for Teri, Toni, Isherwood, Cliff, Ann, and Altoon. “They were tremendously energetic those girls, they were real trouble,” he recalled.32 Garr and Basil were professional dancers working in beach-party movies and television shows such as The Sonny and Cher Comedy Hour, but they were happy to meet him several nights a week to continue dancing into the early morning hours.

They were not strangers to the art world. Through Hopper, years earlier, Garr had been drafted to read Michael McClure’s The Beard in the loft above the carousel on the Santa Monica Pier. Bengston already knew Hopper, Dean Stockwell, and Peter Fonda but then grew friendly with Jack Nicholson through Garr and Basil, who took acting classes with him. Nicholson wrote the slim script The Trip for Roger Corman. Largely a montage of psychedelic special effects, the movie starred Fonda as a director of TV commercials—bad karma from the POV of the sixties—who is given acid by his friends Hopper and Bruce Dern. Nicholson also wrote a part for Garr in his next psychedelic movie Head, a vehicle for the Monkeys. Nicholson remained in touch with the Ferus artists through Ann Marshall, who became his girl Friday in the late sixties after her friend Michelle Phillips had left him. (Nicholson rarely collected contemporary art, preferring Picasso or the erotica of Tamara de Lempicka. However, one Christmas, he bought a large suite of watercolors from Bengston to send to friends as presents.)

Bengston, who titled his radiant enamel paintings after Hollywood personalities—Humphrey, Zachary, Busby—went on to date Diane Varsi of Peyton Place and Bobbi Shaw, who had a role in Beach Blanket Bingo. Bengston introduced Shaw’s roommate Babs Lunine to John Altoon, who was divorced by Fay Spain in 1962. Lunine’s upper-middle-class East Coast background was more boarding school than bohemian, though she majored in art history at the University of Miami before moving to Los Angeles in 1964. She was seventeen years younger than Altoon and was so wholesome and blonde that both Bengston and Altoon referred to her affectionately as “Fluffy.” She married Altoon in 1965.

Bengston, too, settled down. His girlfriend, Penny Little, was registrar of the Pasadena Art Museum. After leaving Ferus, Bengston represented himself, showing and selling out of his studio as well as loaning work for gallery and museum exhibitions. Little helped him organize a system for keeping track of his work. (He had had such difficulties getting work returned that he asked the Whitney Museum of American Art to pay him for loaning his work to their prestigious biennial exhibition. The museum refused.)

Handsome and charismatic, Bengston had little difficulty selling his own work for sizable sums. The work was strongly backed by critics such as John Coplans, who wrote, “It would not be too much to say that by the early sixties Bengston had probably extended the notion of a complex synthetic order of color far in advance of anyone else working at the time.”33 After he had finished a group of what he termed “Dentos”—sheets of thin metal that he had beaten with a ball-peen hammer and then sprayed with lapidary-colored patterns of lacquer—he agreed to a show in 1970 with Riko Mizuno, who had split from a partnership with Eugenia Butler to open her own gallery at 669 North La Cienega Boulevard. Bengston insisted that the show be lit only by candles on stands that he had built so that flickering illumination would cast changing shadows over the glistening, irregular surfaces of the Dentos. Unfortunately, the paintings could barely be seen at all. “That went over like a turd in a punch bowl,” he said.34 It was his only show there. “I always felt that I was the best,” he later said, with a dry laugh. “I think everyone would agree with me that I had a very inflated opinion of myself.… I burned a lot of bridges and was very, very stupid.”35