CHAPTER SEVEN

Glamour Gains Ground

In the early 1960s, Larry Bell worked part-time at the Unicorn coffeehouse on Sunset Boulevard, walking distance from Barney’s. The Kingston Trio and Judy Henske performed regularly at the Unicorn, but the acoustic scene was about to give way to electric rock. It was at the coffeehouse that a well-to-do young man with a tenor voice, David Crosby, met producer Jim Dickson, who put him together with Jim (later Roger) McGuinn, Gene Clark, Michael Clarke, and Chris Hillman, an electric folk-pop group conceived of as the “American Beatles” but known, by 1964, as the Byrds. Dickson was friends with Dennis Hopper, also a regular at the Unicorn. “That is where I first heard ‘Howl’ read by Ginsberg. And Freddy Engelberg was playing guitar,” Hopper recalled.1 Engelberg also acted in The Beat Generation with Fay Spain, Altoon’s first wife, before releasing two albums of his own music.

Occasionally, Bell played his own twelve-string guitar at the Unicorn and hung out with the musicians. Since he watched the door, he would slip in friends for free, including the Grinsteins. Hopps had brought them to Bell’s studio with the warning, “Listen, this is going to look really weird to you but you have to believe it’s art.”2 The Grinsteins embraced the artist and the era. Elyse declared, “We were straight Westsiders but we were changed by the sixties.”3 Though raised on jazz and swing, they had no problem moving on to rock and roll when Johnny Winter played the Whisky a Go Go.

At Bell’s suggestion, they dropped by the Unicorn one night to watch comedian Lenny Bruce, his sharp features softened from alcohol and drugs. He was friendly with Altoon, who lived near the club. Hopper, a staunch supporter of Bruce’s incendiary monologues, was there that night. He was infuriated when authorities intervened. “They dragged him off the fucking stage,” Bell recalled.4

Bruce was determined to use obscenity in his stand-up act, and the police in various cities were just as determined to stop him. Sherman Block, who later became L.A. County sheriff, arrested Bruce on the charge of violating California’s obscenity law at a 1962 performance at the Troubadour on Santa Monica Boulevard in West Hollywood. Less than two weeks later Bruce faced charges in Chicago following a show at the Gate of Horn. Later in 1962 he was arrested again in Los Angeles for a performance at the Unicorn. “Here I am, living up to my public image,” wrote a defiant Bruce. “A true professional never disappoints his public.”5 Bruce’s many influential friends included magazine publisher and freedom of speech champion Hugh Hefner, who serialized Bruce’s How to Talk Dirty and Influence People in Playboy. Bruce’s greatest supporter was twenty-five-year-old record producer Phil Spector, whose “wall of sound” was perfected in Los Angeles with the Ronettes’ “Be My Baby.”

Spector had moved to Los Angeles from New York in 1963 because he had “tired of the condescension of East Coast session men, and now welcomed the chance to work with the younger, hipper musicians of Hollywood.”6 There were more independent labels recording folk, pop, and rock music in Los Angeles than anywhere else in the country. Spector saw his opportunity and broke the rules of recording by “pushing volume levels way into the red, packing the studio with musicians and instruments, devoting hours to each song.”7 He scorned conservatives fighting Bruce’s scathing free-form monologues about religion and race in America. (After Bruce was found dead of a heroin overdose in 1966, Spector bought the paparazzi photographs of his bloated body to outmaneuver the media. Spector himself went to jail in 2009 for the murder of actress and House of Blues hostess Lana Clarkson.)

Hopper identified with Bruce’s expressed feeling of persecution. Like Bruce, he had a reputation for escalating drug use. After eighty-five takes of one scene in the 1958 film From Hell to Texas, director Henry Hathaway spread the word that he was difficult. By the early 1960s, Hopper was not getting as many offers to act and, inspired by Kienholz, started to make collages and assemblages. The opening of his show at the Primus Stuart Gallery brought out friends Paul Newman and Joanne Woodward. It was as a photographer, however, that Hopper’s true talent emerged.

Before marrying Hopper in 1961 at Jane Fonda’s New York apartment, his fiancée Brooke had bought him a 35 mm Nikon camera for his birthday. She recalled, “It turned out that he was as natural a photographer as he was an actor, constantly taking pictures of everything and everyone he came into contact with that intrigued him.”8

After Hopper lost his paintings in the 1961 Bel Air fire, he dedicated himself to photography. “The artists wanted to be photographed,” he recalls, “while the actors were used to it and I, for one, felt like it was often intrusive.”9 He spent his considerable free time hanging around Ferus and taking photographs of the artists. “Light” artist Irwin with a lightbulb in his mouth, luxe Bell wearing striped trousers and two-tone spectator shoes, cool Ruscha posed in front of a shop with a neon sign. In 1963, Hopper’s photographs were reproduced in Artforum with the bravura endorsement: “Welcome brave new images!”

Hopper was hitchhiking on Sunset Boulevard one day when William Claxton, driving his Ford convertible, stopped to pick him up. They had not met previously but synched quickly over their mutual love of photography and jazz. When they reached Hopper’s house at the top of steep Kings Road, Hopper invited Claxton in and Claxton spent the afternoon photographing the rebellious actor. Both were fans of Charlie Parker, whom Claxton had photographed countless times at the Tiffany Club. “The Bird” fascinated Claxton with his tough demeanor and angelic face. Hopper, too, hung around jazz clubs, including the Renaissance opened by Benny Shapiro.

Dennis Hopper, Double Standard, 1961

Photograph by Dennis Hopper, © The Dennis Hopper Trust, courtesy of The Dennis Hopper Trust

Once, after Thelonious Monk had played the Renaissance, Shapiro asked Hopper to take Monk to the airport. “I went to pick him up and he was in this Victorian house in Watts,” Hopper said. “I went three hours early because he loved to miss planes and just get high at the airport and watch people. He was in bed and high and had pills all over the floor.”10 Referring to William Parker, the hard-nosed chief of the LAPD, Monk took a long, stoned look at Hopper and asked, “Dennis, how could a man with the name of Parker be down on jazz?”

“So anyway,” Hopper continued, “we missed the airplane.”11

Claxton’s acclaimed pictures of jazz musicians earned him a position as art director and photographer for Pacific Jazz Records. A Pasadena native, Claxton had attended UCLA with Hopps and was a regular at Ferus, where he befriended many of the jazz-loving artists, especially John Altoon. On more than one occasion, Altoon would borrow money from Claxton and, to secure the debt, give him a painting. A few days later, Altoon would sneak into Claxton’s studio and retrieve the painting without ever telling him. Claxton solved the problem by commissioning Altoon and Irwin to create album covers of their abstract paintings.

The tall, fair Claxton married short, slight Peggy Moffitt in 1961. A Los Angeles native who initially considered a career in acting, Moffitt became one of the top models of the era with her black eye-liner, pale makeup, and glossy dark hair—the absolute opposite of the California girl popularized by television and pop music. Thanks to her association with the radical young Los Angeles fashion designer Rudi Gernreich, she became a recognizable icon of the sixties.

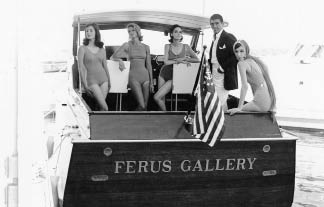

Moffitt and Blum, both extroverts, bonded over their love of the theatrical gesture. One day, she rounded up leggy model Léon Bing and a few other girls. With Blum and Claxton, they all went to the marina for a special photo shoot. Claxton mounted adhesive letters spelling “FERUS GALLERY” on the stern of a cabin cruiser borrowed from his brother. Moffitt and her girls were outfitted in Gernreich bathing suits on loan from the Beverly Hills boutique Jax, where Moffitt had worked as a teenager. Moffitt was furious when “one of the models destroyed one of the bathing suits with a cigarette butt, which I had to pay for.”12 Claxton took a glamorous shot of the pretty girls clustered around Blum, who was wearing his customary blue blazer and assuming an attitude of prosperity. When the photo went out as a gallery announcement, few recipients knew anything about the impoverished Blum. He said, “You have to look like you are doing well and I think we pulled it off.”13 Shirley Hopps recalled that it was all smoke and mirrors. “It was not glamorous. No matter how it looked, Irving was living on about one hundred dollars a month. He had no money but he was a great showman, all facade.”14

Blum, who had aspired to be an actor, could not restrain such indulgence in fantasy. When he spied a Silver Cloud Rolls-Royce parked on La Cienega, he called Seymour Rosen, a photographer who had taken pictures of the Watts Towers and of various artists, and asked him to hurry over to the gallery. When Rosen arrived, Blum hustled him across the street and assumed the pose of the putative Rolls owner. “I need to send a photo to my mother in Phoenix to show her I am doing all right,” he said with one of his hearty laughs.15 Clearly, Ferus had moved on from its chaotic Beat origins.

Ferus Gallery yacht with Irving Blum and Peggy Moffitt on the right

Photography by William Claxton, courtesy of Demont Photo Management, LLC

Thanks to Moffitt, Gernreich invited Ferus artists to parties at his house behind a Moroccan wall on Laurel Canyon where he lived with Oreste Pucciani, chairman of the UCLA French department and authority on Jean-Paul Sartre. The house featured Gernreich-designed floors of burnished leather squares, with furniture by Marcel Breuer and Le Corbusier and art by Ruscha, Bell, and Rauschenberg. “Rudi loved to have artists around,” Bell said. “He had great parties with fancy people. We’d clown around and he was happy to have an entourage of crazy people as well as fashion people.”16 It was at one such party that Craig Kauffman met fashion-model-turned-photographer Patricia Faure, who took pictures of the Ferus artists in a number of antic poses.

Gernreich was the first fashion designer since Christian Dior to become a household name, thanks to the debut of his topless bathing suit as well as unisex clothing. Born in Vienna in 1922, he and his mother came to Los Angeles with other Jewish refugees in 1938. His father had committed suicide in 1930. He attended L.A. City College and initially hoped to be a dancer, studying with choreographer Lester Horton, who was considered the West Coast Martha Graham. While dancing, he worked part-time designing fabrics and then clothes for various small firms in New York, ultimately returning to Los Angeles feeling discouraged by the French couturiers’ monopoly on taste.

His bra-free jersey swimsuits, knit tube dresses, mini-dresses, and other clothes were carried by Jax, Jack Hanson’s cutting-edge Beverly Hills boutique. Hanson, retired shortstop for the Los Angeles Angels, had designed the fitted and tapered Jax slacks, with the zipper up the back instead of on the side, favored by Jackie Kennedy and the period’s curvy movie stars Marilyn Monroe and Elizabeth Taylor. On any given afternoon, he could be found driving around Beverly Hills High School in his 1934 white Rolls-Royce and inviting the cutest girls to work in his store. His wife Sally Hanson became his chief designer, and as profits soared, they opened a “brutally private” nightspot for their exclusive clientele in Beverly Hills called the Daisy.17 Hairstylists Vidal Sassoon and Gene Shacove, whose lively love life inspired the movie Shampoo, socialized at the Daisy with their celebrity clientele: fashion models, actresses and actors, socialites, movie moguls, and international jet setters.

Hanson and Gernreich eventually parted company. Not everyone could accept his increasingly controversial designs. After Gernreich received the Coty American Fashion Critics’ Award in June 1963, Norman Norell, known for his sequined gowns, returned his own Coty award in protest. The following year, Gernreich launched his topless bathing suit. Gernreich said, “Baring these breasts seemed logical in a period of freer attitudes, freer minds, the emancipation of women.”18 With Moffitt modeling, Claxton took photographs that emphasized the modern, graphic quality of the swimsuit. Gernreich initially did not intend to produce the suit but Diana Vreeland at Vogue convinced him otherwise.

Gernreich headquarters at 8460 Santa Monica Boulevard was a khaki-colored square stucco building with twelve-foot panel doors with his name in chrome letters. Three walls and the floor of the showroom were white, one wall was khaki burlap. The room was furnished with black leather Breuer chairs and sofa. Artist Don Bachardy, the partner of author Christopher Isherwood, created sketches for Gernreich’s dresses.

In 1965, Moffitt went to New York where, in the studio of photographer Richard Avedon, she met Vidal Sassoon, who had revolutionized hairstyling in London. When Sassoon came to Los Angeles a few months later, Moffitt introduced him to Gernreich. Sassoon created architectural haircuts that perfectly complemented Gernreich’s graphic, structured fashions. A mutual admiration society was born, and that was the beginning of the end for teased, bouffant hair.19