71

“HAND IN MY POCKET ”:

DUALITY

“Hand in My Pocket,” the fourth song on Jagged Little Pill and the second single to be released from the album, is a song about opposing forces. “I’m broke but I’m happy,” Morissette sings. “I’m poor but I’m kind/I’m short but I’m healthy, yeah.” Morissette, who was only nineteen at the time she wrote those lyrics in 1994, wanted to write an anthem for the youth of Generation X, who were labeled from the outside as “slackers” and “burnouts” by their elders, who saw a sea of flannel and ennui and decided that the kids were simply not alright. But what Morissette wanted to stress about her peers was that they contain

multitudes and unknown depths; even if they seemed to be floating through life, they were roiling underneath the surface. People are kaleidoscopic and unpredictable. They can be sane but overwhelmed, lost but hopeful. They can use one hand to play a piano and the other to hold themselves steady. “Hand in My Pocket,” from that first trademark harmonica lick, is a hopeful song; it says that it is OK to feel conflicted or torn apart or even exhausted. It’s OK to not have it all figured out just yet. It says everything is going to be fine, even when the world is confusing and unpredictable. All we have to get through it are our own two hands, and they are capable of doing so much.

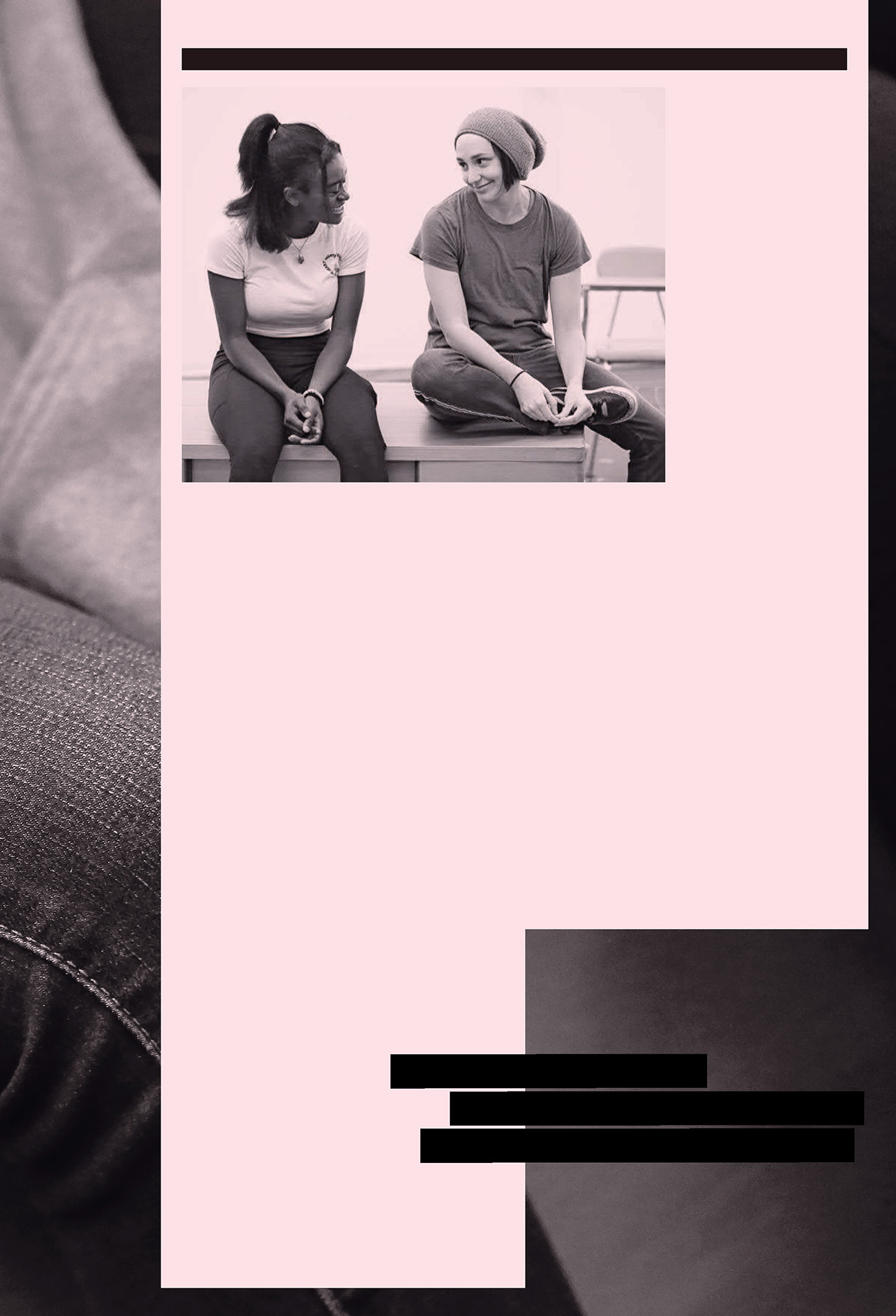

In the Broadway show, “Hand in My Pocket” comes early in the first act, as Frankie (Celia Rose Gooding) and her girlfriend, Jo (Lauren Patten), hold a meeting for their activist club at school between classes (as it turns out, they are the only two members). Frankie laments her mother’s

controlling, nitpicking ways and says she fears that as a black queer woman, she will never fit in easily

with her clean-cut, white-as-milk family. Jo feels similarly displaced. “It could be worse,” she tells Frankie. “Your mom just yells at you. Mine prays for me.” Her Fox

News–watching, pearl-clutching mother insists that Jo go to church socials to try to “pray the gay away.” She makes Jo, who prefers to wear track jackets and slouchy beanies, wriggle into a scratchy hot-pink cardigan that makes Jo feel so uncomfortable in her own body, she begins to shake. Both Frankie and Jo have real problems, real conflicts.

And even though they are still young, they already know what it is like to feel isolated and anxious, out of step with the world around them. But they do have each other. And through each other, they have access to joy.

In the context of the show, “Hand in My Pocket,” takes on a new resonance; the struggles that Morissette felt as a member of Gen X still apply to the young people of Gen Z. Young people still feel misunderstood and yet optimistic, terrified and yet attuned and alive. If anything, the song feels deeply prescient for this time, like a message in a bottle sent from twenty-five years ago to remind us that we are not alone in feeling adrift. Lyrics like “I’m young and I’m underpaid,” and “I’m tired but I’m working,” apply more than

ever in a world where young people like Frankie and Jo will graduate into one of the most extreme recessions the country has ever seen. No one knows the future now, and all we have to hold on to is the knowledge that those before us had no clue what was to come and kept going anyway. When Jo grabs Frankie’s hand and starts singing, it feels like an invitation to let go, to cut each other a little bit of slack. They both begin to dance, first in an imaginary rock concert and then, with the full chorus, in a rousing step number—Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui, the choreographer, said he put in stepping because he wanted a style that would allow the dancers to make noise with claps and slaps, emphasizing the theme of hands running throughout the song. There is a newfound exuberance to the number in the show. Whereas the original music video for the song was understated, as Morissette stood on a crowded Brooklyn street in black and white and let the world pass her by while she sang calmly about all the different aspects of her complex and ever-changing self, now Frankie and Jo turn their complexity into the street party itself.

“I think it’s one of the most joyful moments of the show,” says Patten. “It’s sort of Jo’s philosophy. I think that everybody is this or that. And I think that perhaps in our generation, we might just be more open about it and more accepting. Our joy is complicated. It is a joy that doesn’t come wrapped up in a bow.”

“Young people still feel

misunderstood and yet optimistic,

terrified and yet attuned and alive.”

misunderstood and yet optimistic,

terrified and yet attuned and alive.”